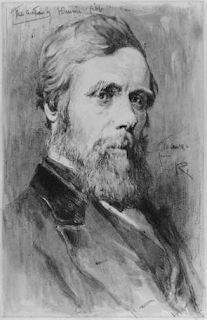

William McCombie (1809 – 1870), farmer, self-educated

joint founder and first editor of the Aberdeen Free Press.

From: W. Robertson Nicoll, M.A.

William McComhie, the

editor of the Aberdeen Free Press, and perhaps, after Hugh Miller, the

most notable among the self-taught men of Scotland.

To say that Mr. McCombie should not be forgotten is to say too little.

He was never much known beyond his own district of the country, and no

one who was acquainted with him, however slightly, or who came under the

range of his influence, will ever forget him. He ought to be known much

more widely than he is, and a full record of his career could hardly

fail to take a place among permanent biographies. A "son of the soil,"

born in a frugal Aberdeenshire farmhouse, with only four or five years

of parish schooling, he became at a very early age the centre of

progress in the region where he lived, and ultimately, it is not too

much to say, the chief Liberal force of Aberdeenshire. He commenced to

publish when he was little more than twenty years old, and wrote books

full of strong thought and eloquent expression to the end of his days.

But his real greatness did not come from them, nor even from the work he

did as editor of a newspaper and an apostle of political Liberalism.

It lay in his grand character. He was one of those unspeakably pure and

exalted souls in which Puritanism sometimes perhaps rarely flowers. On

those who came close to him and especially on worthier spirits he acted

with a force so uncommon that nothing else came near it. For true

individual inborn greatness, he seemed to stand alone and along with

this went perfect refinement and a deep if somewhat shamefaced

tenderness. As one who knew him well testifies, his writing was only

part of the man; the full stores of his mind only came out in converse

with congenial spirits.

"Not a few will recollect the keen intellectual enjoyment, the vigorous

impulse,

they derived from these conversations. They will recollect the treasures

they bore away from an evening's converse with one who laid his hand

lightly and easily on widely-severed provinces of literature and

philosophy, and whose suggestive talk was steeped in that knowledge

which has never got, and never will get, into books. There will also be

a returning sense of that intellectual awe which was kindled at the

sight of a mind instinctively delighting to coast the shadowy margins of

the known, and to take occasional fearful and reverential incursions

into the void beyond. And with these recollections, provided they are

those of intimacy, there cannot fail to mingle thoughts of the delight

with which he who is dead looked upon all enthusiasm, however alien in

its object to his pursuits, of the tenderness with which he treated

youthful thought, however crude and shapeless, and of the width of his

intellectual sympathies. . . .

There is one side, the best side, of his life, which ought not to be

uncovered at the street corners. The last person in the world to flaunt

and strut in subscription lists, or to seek publicity for his deserts,

he would have hated to hear his good deeds spoken of, and the veil which

he cast over his countless acts of charity and kindness ought not to be

lifted."

Mr. McCombie used to say that one of the first things lie remembered was

the risp of the sickle in the harvest field, and he never ceased to be

an ardent and successful farmer. His early essays were written, soon

after he had ploughed from six to six, others after he had held the

scythe through a long summer day. On coming to Aberdeen to start the

Aberdeen Free Press in 1853 he still retained his farm of Cairnballoch,

near Alford. It is never an easy thing to start a new paper, and the

fact that the editor was only to give to it part of his energies looked

unhopeful.

But he wrote himself: "We start on a course of unknown interest,

checkered with peril no doubt, but radiant with hope. We press on

towards no uncertain goal; and, though we know somewhat of the courage

and patience demanded of us, we gird up our loins for it anew with

'heart and hope,' venturing ever to appropriate some encouragement from

the fact that the path of the true and brave is cheered by many a

wayside flower and refreshed by the gushing forth of many an unbidden

spring."

Progress at first was slow, but it was sure. From the beginning Mr.

McCombie had the literary aid of Mr. now Dr. William Alexander, and the

paper soon became not only solid, but interesting. Andrew Halliday was

secured as the London correspondent, and wrote bright amusing letters

which were always eagerly read. The news of the district was well

arranged, and the editor was quite as competent to deal with farming as

with more abstruse subjects. He respected his readers' intelligence, and

treated in a serious fashion the most serious themes. Great space was

given to reviews of books, which were written with courage as well as

with ability, and condemned when condemnation was merited. In this Mr.

McCombie secured the aid of his friends, including some of the more

thoughtful Nonconformist ministers around. The principles of the paper

made even more rapid progress than the journal itself, and Aberdeenshire

from being Tory became one of the most pronouncedly Liberal counties in

Scotland. The Free Press is now one of the best and most influential

daily papers in Scotland.

McCombies have been present in and around the Vale of

Alford, which lies about 30 miles west of Aberdeen, since at

least the early 18th Century. This tribe was remarkable for the

number of high-achieving individuals that it produced. Its

geographical origins and its arrival in this agricultural area

of Aberdeenshire has been dealt with elsewhere (see William

McCombie (1805 – 1880), “Creator of a peculiarly excellent sort

of bullocks” on this blogsite). Alford McCombie individuals

who were successful in life included members of the Established

Church, the legal profession, colonial administration,

manufacturing and commerce, and agriculture. The agricultural

interest was especially strong in the breeding and feeding of

high-value, black cattle, which are now called Aberdeen-Angus.

At the 1851 Census of Scotland five farms in

and around the Vale of Alford were being managed by members of

the McCombie lineage, Tillychetly - Charles McCombie (1803);

Waulkmill – Alexander McCombie; Nether Edindurno – William

McCombie (1810); Tillyfour – William McCombie (1806);

Cairnballoch – William McCombie (1809). Another relative,

William McCombie (1803), was the Laird of the Easter Skene

estate, which lay half way to Aberdeen, but who also owned a

farm in the Alford area. All these establishments were involved

in cattle production. The most prominent and internationally

-important farmer was William McCombie of Tillyfour, generally

considered, along with Hugh Watson of Keillor Farm, Angus, to

have been the most significant developer of the Aberdeen Angus.

Cairnballoch Farm and the early life of

William McCombie (1809)

The farm of Cairnballoch was located about 3

miles south of Alford in the direction of Craigievar Castle,

then the seat of the Forbes family. Cairnballoch, which was

owned by Lord Forbes, consisted mostly of undulating, “brae-set”

land. At the 1851 Census of Scotland it encompassed 115 acres

and typically four labourers were employed there, thus making it

a medium-sized farm in this decidedly rural part of

Aberdeenshire. William McCombie (1809) said that one of his

earliest memories was the risp of the sickle in the harvest

field but the farm was also engaged in cattle production.

William McCombie (1771) was the father of

William McCombie (1809), the subject of this story. William

senior was born at Logie Coldstone, a village lying about 10

miles south-west of Alford and, at some date before 1809,

William senior became the tenant of Cairnballoch

farm. According to James Macdonell (see below), William was

responsible for the reclamation of much land on the farm from

“rugged moorland and stony hillside”. He married his cousin,

Marjory (May) McCombie, at Tough a few miles east of

Cairnballoch about 1808. Marjory also hailed from an

agricultural background. The marriage does not appear to have

been very fecund, apparently the only child being William

McCombie junior, who was born at the family farm in 1809. It

was clearly expected that he would follow in his father’s

footsteps and become a farmer and, from an early age, “… he was

charged with the duties of the farm and while he was still a

youth the chief share of the work fell to his hand. At an age

when most lads are still at the grammar school, he was holding

the plough and among the young men of the district he saw no

more noble exemplar of life than that presented by the farm

labourers or the farmers’ sons who, when the work of the day was

done, thought of nothing but frolic or sleep”.

There is a frustrating lack of factual

precision concerning events in the formative years of William

McCombie (1809)’s life. What is available mostly comes from

recollections of associates, presumably drawing on conversations

with William and the most important of such sources is the

obituary written by James Macdonell, a one-time reporter with

the Aberdeen Free Press, which was published in the Spectator in

1870 following William’s death. William McCombie may only have

enjoyed four or five years of village schooling, perhaps between

the ages of about eight and thirteen (1817 – 1822). After all,

how much formal education would a farmer have needed in the

early 19th century?

William’s mother may have been involved in

his home learning and the Bible is said to have been a

significant reading primer in this deeply religious

household. What must have become clear at an early age to those

around him was that the lad had developed exceptional literacy,

which quickly progressed into a prodigious capacity for

self-learning. It was later remarked that one of his defining

characteristics was a lack of self-publicity. How true. In

subsequent years, when William was writing profusely, the one

topic he never covered was himself, his home life and his early

experiences. That William’s intellectual potential should

blossom in social circumstances which lacked articulate

companions is little short of remarkable and must surely have

had a significant genetic component in its determination. The

many achievements of his McCombie relatives tend to support such

a notion.

William McCombie (1771) died at Cairnballoch

in 1849 at the age of 78, though his son, William McCombie

(1809) had almost certainly taken charge of the farm at an

earlier date. At the 1841 Census, while William senior was

identified as the head of the household, both he and his son

were described as “Farmer”. One data set, that relating to

participation in local ploughing matches, indirectly suggests

that the year of succession may not have been later than 1845,

when William junior was 36.

William McCombie (1809) and ploughing

matches

The ploughing match was one of two key

events, the other being the annual cattle show, in the local

agricultural calendar of rural Aberdeenshire in the mid-19th century. In

his novel “Johnny Gibb of Gushetneuk” by William Alexander (see

below), which was inspired by Aberdeenshire and Banffshire

village life in the 1840s, there is an excellent description of

the mythical “Glengillodram Ploughing Match”, which highlights

the significance and conduct of such events. The ploughing

match was a winter event and, because of the short daylength in

northern latitudes, started at first light. Typically, 30 to 40

competitors would assemble on the ploughing ground with their

pairs of horses, well-groomed, perhaps with tails and manes

plaited and with harness spotless. Competition was intense and

the crowds of spectators were highly knowledgeable. A single

ploughman controlled both the horses and the plough, and he cut

his first, or “feirin”, furrow with great care, regarding both

straightness and constant depth on the patch of field allotted

to him. He then added another 30 or 40 furrows carefully

aligned with the first and evenly packed. (Anyone who

ventures his/her skill at ploughing with horses, as the author

has done, quickly finds that it is utterly exhausting.) There

were usually three competitions, one for the best ploughing

performance, one for the best turned-out pair of horses and one

for best-kept harness, but the first-mentioned was the one which

carried most prestige. The farmer providing the ground would

throw supper for his friends and the judges, though the

ploughmen would not usually be present. They, instead, received

a ploughman’s lunch, with whisky, during the competition. In

the late evening there would be a ploughman’s ball, open to all

levels of village life, from the laird down to the day

labourers, with vigorous dancing to fiddlers and/or a piper

until a late hour. Usually there would be a break in the

proceedings for oatcakes, cheese and whisky toddy. The next

morning the manual labourers would have to rise after a brief

sleep to go back to work.

Ploughing matches have been a feature of

Scottish rural life since the late 18th century and

they were established in the Vale of Alford by the late

1830s. In the decade 1835 – 1844 the Aberdeen Journal recorded

82 separate mentions of ploughing matches. This jumped to 288

mentions in the following decade, with a similar frequency, 257,

between in 1855 – 1864. The McCombies of Cairnballoch did not

support ploughing matches at all before 1845 but in the period

to 1851 are known to have provided help on 14 separate

occasions. Their interest in ploughing matches then ended

almost as suddenly, there being only one instance of cooperation

recorded after the latter year. Support for ploughing matches

could involve allowing farm servants to compete, providing prize

money, making available the ploughing ground and gifting the

following dinner, acting as a judge, or taking the chair at

dinner, giving a speech or supporting the chairman as

croupier. As will be seen later, William McCombie (1809) showed

empathy with the farm labourers and it seems possible that the

Cairnballoch support of ploughing matches followed a change of

regime at the farm, with the retiral of William senior before

1845. The cessation of support for ploughing matches after 1851

is less easy to explain. William McCombie (1809) did spend more

time away from the farm after this date but he still retained

his lease of Cairnballoch and continued in his role as farmer

there.

The intellectual development of William

McCombie (1809)

According to James Macdonell, “at times he (William

McCombie (1809)) could get no more nourishing intellectual

fare than the “Penny Cyclopedia” or Harvey’s “Meditations among

the Tombs”. Nevertheless, he became an insatiable reader. In

the long evenings of winter, he read by the light of the kitchen

fire and when sent to Aberdeen with the carts he seated himself

on the top of the stuff which he was bringing to Cairnballoch

and read as the horses jogged slowly home.” William did not

simply absorb knowledge, he also analysed the information he

acquired. One subject over all others had a profound impact on

the young man and that was religion. Having been brought up in

a strictly religious household where “… the Bible still keeps a

position of almost Hebrew supremacy. It is emphatically the

Book of Books, morning and night it is read with such eagerness

and such thoroughness as can be matched only in the studies of

the commentator …”, his scope for original thought was thus

constrained by fundamental religious dogmas indelibly imprinted

in his youthful mind and afterwards ever-present to guide and

direct his thinking processes. Within these boundaries he

became “an independent, original and vigorous thinker”.

William McCombie (1809), while still a young

man oppressed by the hard, physical work of the farm (ploughing

“from six to six” or holding the scythe “through a long summer

day”), started to set down his thoughts on paper in the form of

essays which were eventually collected together in his first

book. “The stone windowsill of a little opening in his father’s

cottage he used as a writing desk and for the want of a

convenient seat he had to kneel on a large chest.” The book

that emerged he called “Hours of Thought”. It was published in

London in 1835 when he was 26 and consisted of a series of

essays which bore the titles, “On

intellectual greatness”, “On moral greatness”, “On poetry”, “On

luxury”, “Obligations of Christians to devote their energies to

the dissemination of Christianity”, “On some defects in

evangelical preaching”, “On Christian Union”, “Future prospects

of this world”. The precise dates of creation of the individual

components of the book are unknown but must have extended over

several years. The book enjoyed some success and was published

in a second edition in 1839 and a third edition in 1856.

If William McCombie (1809) had ceased his

intellectual endeavours at that point, it would still have been

truly remarkable that a 26-year-old farmer from a peripheral

area of Aberdeenshire, with only a few years of basic education,

limited access to books for self-education and no opportunity to

debate and refine his thoughts with educated colleagues, should

have produced and got published a book of such breadth. The

title of this first book indicates both William’s great

strengths and his limitations. His confined upbringing and

education left him with a greater reverence for ideas than for

facts, a limited appreciation of the fruits of science but

little sympathy for quantitation and the scientific method for

testing ideas. His technique of inquiry was to absorb the

writings of others and then to think deeply about what he had

learned, subjecting all constructions to his own mental tests,

before producing his synthesis of ideas on a given topic. The

areas where he experienced greatest comfort were Theology (the

study of the nature of God and religious belief), Philosophy

(the study of general and fundamental problems concerning

matters such as existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and

language) and Metaphysics (abstract theory with no basis

in reality). The result was that his readers were often

left in awe at his erudition and use of language but baffled by

the complexity and length of his writing, especially when

dealing with religious and philosophical topics. The obituary

on William McCombie in the Buchan Observer described his large

library at Cairnballoch as being “filled

with treatises of revolting dryness on the controversies of the

Christian sects”. Some

of his own works were impenetrable to the general reader. Often

reviews of his books indicated that the reviewer fell into the

“baffled” category, since comments were reduced to the

employment of superficial but complimentary generalisations, for

example, “By all those who

are interested in the harmony and consistency of religious

truth, it will be highly appreciated.”

It would probably be fair to say that

William developed a high local reputation as a theologian,

philosopher and social commentator but failed to make an impact

on the national or the international stage in these

fields. Still, those who met and conversed with him invariably

came away with a powerful impression of an honest and highly

intelligent man, always capable of original thinking. As the

Buchan Observer put it, “But

it was in conversation that his powers were most vividly seen”.

After his first book, “Hours of

Thought” (1835), William McCombie (1809) was involved with

several other major publications as author, or author/editor, or

editor. They are listed here, with date of publication. In

addition, he was also the creator of many newspaper articles.

1838. “The Christian

Church considered in relation to Unity and Schism” (author). In

this theological book he dealt with the importance of

maintaining Christian unity and the sinfulness of actions that

promote division.

1842. “Moral Agency, and Man as a Moral

Agent” (author). The Baptist Magazine reviewed this book

with the following statement. ““There are two great inquiries,”

Mr McCombie states, “embraced in the following treatise viz 1st What

is moral agency, considered in itself? And 2ndly. What are the

powers and conditions of man in relation to it? Under the first

the author has endeavoured to ascertain what the nature of moral

agency is and what are the indispensable conditions of its

being exercised; in doing so he has been led to inquire what the

kind of knowledge is which forms properly the basis of moral

agency and how is it obtained; and has endeavoured to meet the

difficulties which arise from the divine foreknowledge and to

subvert the position that mind in its actings is subject to the

law of causation, or that in choosing and willing, it is not

free. In the second part of the treatise the writer has entered

on the inquiry what the powers and capabilities and resources of

man are , considered as a moral agent; in what respects and to

what extent he has considered in this light been affected by the

sin of Adam or the fall and in what respects and to what extent

by the work of Christ.” Erudite theologians may have found such

theorising intriguing but for most adherents the content of the

book must have been perplexing.

1845. “Memoirs of Alexander Bethune

embracing selections from his correspondence and literary

remains” (author/editor). Alexander Bethune was one of

three brothers born into a peasant family in Fife in

1804. Family poverty precluded him from being apprenticed in

any trade, resulting in Alexander becoming an agricultural

labourer. Despite his strained circumstances, he proved to have

great skill in expressing himself in writing. The following

example of his poetry shows the extent of his talent in

illustrating the circumstances of his life.

“And for my fare I ate a crust as dry,

And drank from the ice-girded stream, and

rested

Upon a stone from which I swept the snow

My dining-room had clouds for tapestry,

Mountains for walls, the boundless sky for

ceiling,

And frosty winds for music whistling

through it.”

He composed a variety of works including

“Tales and Sketches of the Scottish Peasantry” and a series of

lectures on economics (with his brother John), designed to help

the working man better his financial circumstances. The Bethune

brothers also wrote stories and poetry, and, after John’s early

death, Alexander published a collection of his sibling’s poetic

works. Alexander Bethune wanted to reform the relationship

between working men on the one hand, and the tenant farmers and

land owners on the other, which he saw as exploitative. He

believed a change in such conditions would remove the feelings

of bitterness, negativity and addiction to charity engendered in

the working class, thus acting as a stimulus to them taking a

positive attitude to the improvement of their conditions of

life. The Bethune brothers practised what they

preached. Alexander and his brother built their own house with

£30 and then invested a £5 fee from Alexander’s first book in

adding an extra storey, which they hoped eventually to

let. Alexander saw economics as a more important subject than

geography and thought it should be taught in schools to all

pupils. William McCombie (1809) struck up a correspondence with

Alexander Bethune. It is clear the two of them had a mutual

attraction arising from their similar circumstances, both being

self-taught, talented thinkers and writers, and being proponents

of rural social reform. The two met in 1842, a year before

Bethune’s death, when Alexander walked from Arbroath to

Aberdeenshire. Before his demise at the age of 39, when illness

precluded further intellectual work, Bethune entrusted his

archive to the care of William McCombie (1809) and this

biographical work about his friend was the product.

1850. “The

foundations of individual character. A lecture”

1852. “Modern Sacred Poetry” (editor).

Curiously, this volume was published by the Presbyterian Church

of Canada. It is a substantial collection of works extending to

370 pages and it is presumed that the selection of works to be

included was made by William McCombie. The preface to the first

edition, written by William, was dated “Cairnballoch 22 June

1852”. William McCombie saw sacred poetry as having “a high

value both as ministering to spiritual enjoyment and as

influentially entering into that great educational process –

that training of the spiritual and moral nature – essential

alike to right doing, right being and to ultimate

happiness.” It is interesting to note that in early 1853 the

printer and friend of William McCombie (1809), George King,

exported two boxes of books from Aberdeen to Quebec, which may

have been connected with this poetic compilation by William (see

below).

1852. “Use and abuse or right and wrong in

the relations to labour of capital, machinery and land” (author). This

essay on the economics of capital and labour, especially as it

applied to the relationship between landowners, land occupiers

and labourers in (then) current, rural Scotland appears to have

been influenced by the views of his friend Alexander Bethune,

but also by John Stuart Mill, the philosopher, social reformer

and economist. The book consists of two lectures produced

independently (for delivery to local Mutual Instruction classes

– see below) which were then linked by an introduction, written

later. Interestingly, one comment to a lecture audience

remains, where William admits that he tended to write and talk

at too great a length. “(A) great part of a lecture I delivered

last July to a neighbouring class was occupied with these

enquiries; to resume them here, though it might be important to

my general object, would be unendurable by your

patience.” William McCombie (1809) saw the fundamental defect

with the then current arrangements as being an unfair

distribution of capital between the different social

strata. “The distribution of the elements of wealth presented

by nature to man and of the constituents of wealth secured from

Nature by man forms the great social problem of the times. Not

only does this problem underlie all the various schemes of

communism and organisation of labour; but, discerned or not, is

at the bottom of all jealousies between employers and employed –

of all strikes and combinations and though more indirectly not

the less truly of all questions of rent, protection and the

incidence of taxation.” He was heavily critical of individuals

who accumulated capital but did not invest it to generate

greater value. In this context he was particularly critical of

owners of large tracts of land which were turned over to

sporting estates and the rental income squandered, rather than

being invested in soil improvement for more productive

agriculture. “Take the case of a proprietor of land in the

predicament already referred to. He keeps a stud, or a pack of

hounds; he passes the gay “season” in the metropolis, gives

expensive entertainments, patronizes opera artistes

…”. However, he did not absolve the working class from a

measure of blame for its condition. The monotony of manual

labour combined with moral deficiency of individuals were seen

by him as major influences. “These causes, combined with

defective training in childhood and early association with the

contaminated and deprived, induce a hand-to-mouth and too often

dissipated life.” He also saw alcohol consumption as a major

problem. “How many in all classes are poor – become bankrupts

indeed – because of the habits of expense they allow to grow on

them. How many a one has the indulgence in strong drink made to

go hatless and shoeless and coatless and even shirtless, yea

brought to a premature grave - leaving probably a widow and half

a dozen orphans on the poor roll or in the workhouse.” Tobacco

consumption received a lashing too. This was ironic for someone

whose family wealth had been significantly based on tobacco

importation and snuff manufacture! “…millions’ worth of the

products of the earth and of human labour combined annually

vanish in mere smoke …”. William McCombie (1809) also perceived

another problem and that was the use of borrowed money for

speculative investment, for example on railway shares. The

modern financial system would hardly have agreed with that

notion!

William saw four general schemes for the

distribution and redistribution of wealth in society. 1. To

promote and fence large distributions in the hands of

individuals by means of social usage and public law. 2. By law

to restrain accumulation and to compel distribution. 3. To

leave the distribution of wealth free, like its production, to

the spontaneous operation of social forces. 4. To make the

distribution of wealth entirely a matter of social arrangement

according to one or other of the schemes of communism. He

rejected scheme 4 on the grounds that communism “abolishes

self-action and places individuals entirely under the direction

of others”. Scheme 1 represented the then current position,

where law (for example the Law of Hypothec and the Law of

Entail) protected the accumulation of wealth derived from land

ownership, in a few hands. He theoretically supported Scheme 3

but admitted that no society was known which operated in this

way “in a state of enlightenment and moral elevation”. He

therefore concluded that there would have to be compulsion in

the redistribution of wealth, through the reform of the laws of

the country. One has to admit – that is what has happened!

The history of land ownership and

management in Scotland was a particular target of William

McCombie’s ire. He regretted the transformation of the Highland

chief from guardian of his people to landlord. “He no longer

shares fish, fowl and fauna with his retainers but keeps them

for himself and persecutes tenants who take them. The chief may

no longer live amongst his people but hundreds of miles away,

often in London. He has no obligation to make a contribution to

his local community except when they fall into pauperism. He

now may also claim the right to clear the land of its people,

land where their ancestors had an expectation to live. The

tenant not only has to pay rent to the landlord, but he also has

to compete for a new tenancy at the end of a lease.” William

McCombie’s radical solution to such ills was essentially land

nationalisation, where the Government would own the land and let

it to individuals on more favourable terms than the current

owners.

1857. “On education

in its constituents, objects and issues” (author). This

volume contained a series of essays and lectures by William

McCombie. In 1850 he had been one of a large number of Scotsmen

who had subscribed their names to a document calling for the

reform of the national educational curriculum, based on

perceived deficiencies in then current arrangements, ie

education at the hands of the Established

Church. Interestingly, James Adam, the editor of the Free

Press’ rival, the Aberdeen Herald (see below), was a

co-signatory.

1860. “The Literary Remains of George

Murray with a sketch of his life” (author/editor). George

Murray was a Peterhead loon born into straightened circumstances

in 1819. At the early age of seven he showed great persistence

in improving his family’s income by wandering off into the

country and asking a farmer he met by chance for work, to which

the farmer eventually agreed. George was set to herding “the

kye” and was retained in this role by the farmer for six

months. George Murray was then sent home with a shilling in his

hand and a fustian suite on his back. (“Fustian” was a

thick, hard-wearing cloth composed of cotton with linen or wool). Like

William McCombie’s other hero, Alexander Bethune, George Murray

showed an early aptitude for reading. There were few books at

home and George would pick up scraps of newspaper in the street

with which to practise his literary skills. He became

apprenticed to a cobbler about the age of 14 and eventually set

up business on his own account, which he continued until his

death at the age of 40. While working as a cobbler George spent

long hours in self-education, becoming thoroughly acquainted

with poetry, theology and science, especially geography and

astronomy. Eventually he turned his hand to writing and

produced stories, essays and poetry, usually with a local

context. “A tale of Ugie in olden time”, which was described as

having “considerable dramatic merit”, shining out in a rather

barren Buchan creative landscape. An example of his poetry

follows, which attempts to buck up the working class by turning

them to religion.

“Wearied and worn one, stricken

in spirit,

Fret not at feeling the gall in

thy lot;

Seemingly favoured ones do not

inherit

All thy imaginings – envy them

not

Who shall give way to forebodings

of sadness?

Clouds and thick darkness may

compass our way;

But there’s an Eye ever beaming

forth gladness,

Over and near us; look up! He

will stay.”

George Murray was instrumental in setting up

the Union Industrial School for poor children in Peterhead and

taught there for many years, while still pursuing his occupation

as a cobbler. In 1855 he was recruited to work for the Aberdeen

Free Press as Peterhead reporter, a role he fulfilled with great

tact and skill. For the last two years of his life he was

District Editor in charge of both the journalistic and

commercial aspects of the newspaper office. In an obituary, the

Peterhead Sentinel described him as “A man of sterling

integrity, unflinching independence and genuine Christian

character, he was respected while amongst us and will be deeply

regretted and long remembered.” When George Murray died at the

age of 40 from chronic enteritis of many years’ standing

(inflammatory bowel disease?) he left a widow and eight

children. William McCombie (1809) then devised a plan to

publish and sell this volume of George Murray’s work, the

proceeds to be donated to his family. It was divided into three

sections, headed “Tales”, “Essays” and “Poetry” and the price

was 2/6.

1864. “Modern Civilisation and its

relation to Christianity” (author). This was yet another

volume of collected essays by William McCombie (1809)

1869. “The Irish Land Question” (author). William

McCombie was a supporter of the Liberation Society which

campaigned for the abolition of state support to religion. At a

meeting held in Aberdeen in 1867 he moved a resolution, “That

the Irish Protestant Establishment is a gross political

injustice and a fruitful source of national disaffection, that

the subsidising of other religious bodies is equally to be

condemned and instead of lessening the evil only renders it more

intolerable and that the only practical remedy is the withdrawal

of all legislative endowments for the maintenance of religion,

due regard being had to the existing interests of

individuals.” He was

highly critical of the Protestant Ascendancy, the insecure

tenancy of the (mostly Catholic) Irish peasantry and the lack of

investment in land improvement. He toured Ireland to get a

personal acquaintance with conditions there. While he put much

of the blame for the inability of Ireland to support its

population on the big and often absent landlords, he found other

problems too, such as the lack of coal to form the basis of

manufacturing, the size of the population in relation to the

productive capacity of the land (and advocated emigration to

solve this problem) and the reluctance of the peasantry to

changing their agricultural methods. As with Scotland, he

suggested that land nationalisation would be appropriate if the

landlords refused to carry out land improvement works. His

pamphlet, “The Irish Land Question” took the form of a letter to

William Gladstone, then in his first premiership.

1871. “Sermons and

Lectures by William McCombie” (author – the collection was

edited, after the death of William McCombie, by his daughter,

May, who died in 1874). When he acquired a house in Aberdeen,

William McCombie (1809) became a member of the John Street

Baptist Church. On occasions when the minister was absent,

William often took charge of the service, including giving the

sermon. The 29 sermons contained in this volume were written

between 1856, or thereby and 1870. The volume also included two

lectures. There are no dates on the actual manuscripts and some

of the individual works appear to have been prepared in a

hurry. The

titles of the sermons are as follows. “Faith”, “Christ as the

sacrifice”, Christ as the sin-destroyer”, Christ as the source

of the higher life”, “Christ the light of men”, “The teaching of

Christ”, “The origin of the spiritual life”, “Spiritual

freedom”, “Spiritual sonship”, “The two schemes of life”, “The

life of faith”, “True worship”, “The homage of the soul”, “The

reconciliation of the world to God”, “The law in the heart”,

“Service”, “Striving”, “Faith and works”, “He that believeth

shall not make haste”, “Self-denial”, “The thorn in the flesh”,

“The Christian armour”, “The reproach of Christ”, “Ashamed of

Christ”, “The prodigal”, “Sin the great agent of destruction”,

“The permanency of moral habits”, “Overcoming” and “What is

religion?”

It is clear from the

above list of publications that William McCombie (1809) never

set out to write a book as such. Rather he wrote many shorter

items, such as essays, lectures, newspaper articles and sermons

and then subsequently cobbled them together to publish as books

or pamphlets. He clearly subscribed to the idea that God was

beyond human understanding. “Religion

is not, either as to its object, or as to its action on the

mind, to be brought fully within the comprehension of the human

understanding, but that is no reason why we should cease to

regard it rationally.” He was aware of the long history of the

past stored in layers of the earth’s crust and the many

revolutions in nature revealed by this record, but he did not

see such information as impinging on his religious

theorising. In “Christ the light of men” he dismissed the idea

propounded by some philosophers that life is just the result of

the operation of natural laws. “What is life? We cannot

tell. Even in the plant there is something that eludes both our

senses and our physical science. There is a class of

philosophers in these days who think they can dispense with a

principal of life. It will not ordinate in their scheme of

positive science and they ignore it or cast it out. I should as

soon think of ignoring the principle of gravitation.” William

clearly subscribed to the idea of a “life force” which animated

living things.

Mutual Instruction

Classes

“Mutual instruction” is a term which was

originally used to describe the monitorial system of education,

developed by Bell and Lancaster and introduced widely in the UK

and in Continental Europe early in the 19th century,

as a means of providing cheap schooling for poor pupils. In

this system the more able children (class monitors) were used to

teach the less able.

Another early 19th century

development to bring education to the masses was the

introduction of Mechanics’ Institutes, establishments which

provided education, mostly to working men, usually in technical

subjects. The motive for this innovation was partly to improve

the technical skills of the workforce but also to give working

men an alternative in the evenings to intoxication and

gambling. The first Mechanics’ Institute was established in

1821 by Leonard Horner, an Edinburgh businessman. This was

followed by the Glasgow Mechanics’ Institute, which was founded

by Dr George Birkbeck, a Yorkshireman who studied Medicine at

Edinburgh University before being appointed Professor of Natural

Philosophy at the Andersonian Institute in Glasgow (later to

become the University of Strathclyde). In 1800, he provided

free lectures on science and technology for young working men

and later, in 1823, he created a Mechanics’ Institute in the

city.

Mechanics’ Institutes were usually only

sustainable in big cities with at least some philanthropic

employers, manufacturing industry and large

populations. However, the principle of mutual instruction was

later adopted in, and adapted to, other social settings by a

variety of organisations. For example, in 1836 the Caledonian

Mercury, commenting on a course of chemistry lectures mounted by

the Dalkeith Scientific Association, noted that such

associations were spreading across the country offering

instruction to the greater mass of the population and “affords a

pleasing earnest of the dawn of that bright era in the world’s

history when all shall combine for mutual instruction and when

the lights of science shall dispel those clouds of ignorance

which still hover around man’s destiny, and cheer and brighten

the happy home of the humblest labourer and artisan in our free

and happy land.” Provision of mutual instruction classes was

often sponsored by teetotal groupings, such as the Liverpool

Total Abstinence Society. In Windygates, Fife in 1837 the

Windygates Agricultural Association meeting “gave an opportunity

for landlord and tenant, producers and consumers to meet for

mutual instruction in diffusing knowledge of the best means of

production.”

However, the most significant development in

mutual instruction was its introduction to the working class in

small towns and villages, not only as a means of gathering

knowledge in any subject, but also in gaining self-esteem,

writing and presentation skills, and empowerment to take their

own initiatives. In 1842 it was noted that the Wick and

Pultneytown Young Mens’ Mutual Instruction Society had increased

to about 30 members which met every Monday evening. Any member

was at liberty to propose the discussion of an “edifying and

instructing” subject. The Society’s President then nominated

four members to give opinions of the subject on the succeeding

evening, either by written essay or by oral

address. Unfortunately, not all young men were immediately won

over by this new movement. The John O’Groats Journal lamented

in 1845, “It is a pity indeed to see so many young persons

parading the streets at a time when they have an opportunity of

having their minds improved and having additions made to their

stock of knowledge for nothing.”

Rhynie Mutual Instruction Class

The first Mutual Instruction Class identified

in the North East of Scotland was the Craibstone Class, Parish

of Newhills, near Aberdeen. In 1842 it celebrated its first

anniversary with a soiree and ball on the evening of New Year’s

Day. “Some neat and appropriate speeches” were presented on the

benefits of mutual improvement societies. Similar societies

were in existence in Macduff (Banffshire) and Tarves

(Aberdeenshire) by 1844. But it was in 1846 that the most

significant development in mutual instruction occurred in

Aberdeenshire, not close to the city of Aberdeen but in the

remote parish of Rhynie, which in 1841 had a population of

1033. In the New Statistical Account of Scotland of 1842,

written by the minister of the Church of Scotland, the parish

was described as having “only” about 12 dissenting (ie

Non-Conformist) families. But that was quite a high

proportion, given the small overall population of the parish.

Robert Harvey Smith was an intelligent lad,

who was born into a farming family in Rhynie and was only 20

when in 1846 he collected together eleven other young men for a

meeting and submitted a set of draft rules to them for the

formation of a Mutual Instruction Class. Robert would later

attend university in Aberdeen and graduate with a degree in

Divinity. The rules of the class were debated by the attendees

and adopted, with some modifications. The principal aim of the

movement was mutual instruction of its members “by

the reading of essays and criticisms thereupon”. Members were

fined one penny if they were ten minutes late for a meeting

“unless an excuse satisfactory to the majority were given”. In

addition to member essays and talks, lectures by established

speakers were also presented.

The Rhynie Mutual

Instruction Class became very successful. Robert Harvey Smith

recruited a dedicated group of helpers who, over the next few

years repeatedly supported the Class by making

presentations. The cohort included Rev Alex Mackay, FRGS, Free

Church schoolmaster, Rev George Stewart, Established Church

schoolmaster, Rev A Nicholl of the Congregational Church and

John Stuart, Free School, all Rhynie. Schoolmasters and

ministers were recruited from nearby parishes too, such as

Auchindoir, Kinnethmont, Huntly and Lumsden. In addition, local

doctors and veterinarians gave talks. It is remarkable that the

Congregationalists and the Free Church were so heavily involved

and, just a few years after the disruption of 1843, the

Established Church also played its part in this movement which

was heavily dominated by the Non-Conformist churches. Rhynie

was one of the few parishes in Scotland where the Established

Church incumbent was displaced.

The programme of lectures arranged for the

Rhynie Mutual Instruction class in the spring and early summer

of 1847, mostly on science subjects, was as follows. 1st lecture

Rev A Mackay, Free Church, Rhynie “Heat”. 2nd Lecture

Dr Macdonald, Surgeon, Huntly “Anatomy part 1”. 3rd lecture

Rev George Stewart, Established Church, Rhynie “Origin of

Language”. 4th lecture Rev H Nicoll, Free Church,

Auchindoir “Geology”. 5th lecture Rev A Nicoll,

Congregational Church, Rhynie “Astronomy”. 6th lecture

Rev D Rose, Free Church, Kinnethmont “Magnetism and

Electricity”. 7th lecture R Troup jun, Schoolmaster,

Rhynie “Light”. 8th lecture Rev A Mackay, Free

Church, Rhynie “Laws of Motion”. 9th lecture Dr

Macdonald, Surgeon, Huntly “Anatomy part 2”.

At the end of 1847 the Rhynie Class held an

evening festival (such an event was often called a “soiree”) to

celebrate the achievements of the first year. During the

evening nine members of the class delivered their maiden

speeches while the audience “expressed their approbation of each

speaker by successive bursts of applause”. Rev Mr M’Kay and Rev

Mr Nicoll also gave enthusiastic addresses to the meeting. Such

annual celebrations became a standard feature, both at Rhynie

and at other Mutual Instruction Classes. These events were

usually preceded by tea and the presentations were often

followed by music or even by a ball.

While Mutual Instruction Classes were almost

exclusively a preserve of young males, who were mostly employed

in manual work, and the ones who were causing social problems

through drinking and other disruptive activities, in 1848 a

class member, William McConnochy made a presentation on “Female

Education”. In 1851, the Aberdeen and Banffshire Mutual

Instruction Union (see below) mounted an essay competition on

“Female education and training etc”. The winner was farmer

William Anderson of Alford. The Forgue Mutual Instruction Class

in 1851 heard an address on “Female influence and education, and

the indifference of society about these” and in 1854 a similar

class in Kinmuck received a presentation on “Female influence

and its value in the temperance cause”. The Leith-Lumsden class

encouraged ladies to join Female Mutual Instruction Classes at

their 1849 festival. This occasion was addressed by William

McCombie (1809). He was greeted “with much applause”. Such

egalitarian ideas, which William espoused, were rare at this

time.

Robert Harvey Smith was also instrumental in

taking the message of the Mutual Instruction Class to other

parishes outwith Rhynie, initially through a Corresponding

Committee, established in 1847. Two years later this work was

taken over by the creation of the Aberdeen and Banffshire Mutual

Instruction Union (ABMIU), an umbrella body, at a meeting held

in Rhynie, with Robert Harvey Smith as its Chairman. Eighteen

delegates from existing classes attended, though other classes

were unable to be represented. William McCombie (1809) of

Cairnballoch was elected as the first President of the ABMIU,

though it was probably a non-executive position. The entry on

William McCombie (1809) in the Dictionary of National Biography

says, “He

soon showed a taste for literature, and local debating societies

(presumably Mutual Instruction Classes) gave him an

opportunity of cultivating his talents”, but this can hardly be

true. Rhynie was the nearest Mutual Instruction Class to

Cairnballoch, lying about 11 miles distant by road. By the

time the Rhynie Class was established in 1846, William was

already 37 and had established his reputation with a string of

publications, the most prominent of which, “Hours of Thought”

had originally appeared in 1835. His first known contribution

as a speaker to the Rhynie class was in June 1849. It must have

been the case that William was elected President of the ABMIU

because of his already established literary reputation and his

sympathy for rural self-help. He was a figurehead for this

movement, an illustration of what could be achieved in a farming

community through determination, allied with innate ability.

William McCombie (1809)

of Cairnballoch was President or Honorary President of the ABMIU

between 1849 and at least 1856. The ABMIU had as its objective,

“The

cultivation of friendly feeling and sincere cooperation in

everything related to the interests of the Associated Mutual

Instruction Classes and the establishment of others in

favourable localities”. To help promote its message, the ABMIU

published for six months in 1850 “The Rural Echo; and Magazine

of the North of Scotland Mutual Instruction Associations”. It

had a monthly circulation of more than 1,000 but appears not to

have reached a level of sustainability. However, the ABMIU was

still successful in spreading the message about mutual

instruction across the region. At the 4th annual

assembly of the Union, held at Forgue in 1853, the following

information was reported. The

constituent societies (Alford, Auchleven, Drumdollo, Essie,

Gardenston, Grange, Insch, Lumsden, Leochel-Cushnie and Rhynie)

all pursued the self- and mutual-instruction of their members

and the intellectual improvement of the people in their

respective neighbourhoods. They were all non-sectarian in their

constitutions and collectively had 660 members, who had read

1177 essays or papers. They had raised twelve libraries

containing 1206 volumes, presented 132 public lectures, with an

average attendance of 120 and 40 social meetings with a mean

audience of 210. Some papers, written entirely by members, had

been published and 10,260 copies of these distributed. This was

a remarkable achievement and a major contribution to the

education of the rural working class in Aberdeenshire. William

McCombie (1809) must have been proud to be associated with such

a worthy initiative.

William McCombie (1809) appears to have

spoken three times at meetings of the Rhynie class in 1849, 1850

and 1851. His 1849 contribution was particularly noteworthy in

presenting his opinions on mutual instruction. The Aberdeen

Journal reported that, “After

noticing the condition of farm servants and the conduct of their

masters to them, making some remarks on the bothy and large farm

systems and giving a gentle hint to smokers and snuffers he

adverted to a remark which fell from one of the speakers

regarding the acquisition of knowledge. He said that the mind

should not receive knowledge mechanically as the sponge takes up

water and give it forth again without being influenced by it,

but as the lime shell which imbibes it and becoming assimilated

with it is fitted for fertilising the soil on which it is

spread. One of the lectures had been on ghost-seeing – he

trusted there would be but one other ghost seen in Rhynie – the

ghost of ignorance – departing as a certain traditional ghost

once did (Here Mr McCombie gave an account of this ghost and its

last words amid shouts of laughter). One speaker had said that

twelve Mutual Instruction Classes could now be seen from the Top

o’ Noth (a local hill); they all knew the old rhyme – “The Buck,

Belrinnes, Noth and Bennachie, Are the four landmarks on this

side the sea.” He had hoped these would speedily become

landmarks of an intellectual sea which would submerge ignorance

and vice beneath its waves. Top o’ Noth was likely to become

so, the others had yet not that honour.” (Top o’Noth lies close

to Rhynie, the other hills are respectively close to Keith,

Dufftown and Inverurie). It

was reported that William McCombie had given “decidedly the

speech of the evening was frequently interrupted by bursts of

applause and sat down amid loud cheers”. He was clearly admired

by the working class in this locality.

In September 1849 William McCombie

addressed the annual soiree of the Leith-Lumsden Class. “During

the evening a glass of ginger wine was handed round” – a highly

atypical occurrence, as such meetings were usually

alcohol-free. William McCombie (1809) addressed the meeting and

he made his own position clear on the effect of alcohol on

intellectual activity. He disagreed with Burns’ theory of wit

“Leese me on drink”. He held to an older saying “When the

drink’s in the wit’s out”. William attributed the demise of

some associations to their being too narrow and associated with

drink, such as cattle shows. Also, a distinguished literary man

had told him that no one spoke sense after dinner. William

thought they should deal with the whole nature of man. He urged

the young men on mutual instruction courses that mere

intellectual training was insufficient, but that the moral and

spiritual nature of man must also be cultivated.

William McCombie was also known to have

addressed several other organisations involved in adult

education, including the Clatt Mutual Instruction Class and the

Huntly Mutual Instruction Society, both in 1850, the Aberdeen

Young Men’s Literary Union and the Aberdeen Mechanics’

Institute, both in 1854, the Alford Mutual Instruction Society

in 1855, the Oldmeldum Mechanics’ Institute in 1856, the

Bon-Accord Literary Society, the

Free Gilcomston Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association and

at Huntly in 1857, at Aberchirder and separately at Portsoy on “Money

credit and banking” in 1858, and

to the Banff Mutual Instruction Society in 1859.

A brief history of Aberdeen newspapers

It is perhaps not surprising that William

McCombie (1809) should have begun to harbour thoughts of owning

or editing a newspaper as a means of propagating his personal

philosophy on religion, politics and social affairs, poetry and

literature. But before delving into William’s involvement in the

local press in Aberdeen and more widely in North East Scotland,

it will first it be important to set the scene by briefly

recounting the history of Aberdeen’s newspaper titles.

The first Aberdeen newspaper was the

Aberdeen Journal which was initially published on 5th January

1748, by Aberdeen printer James Chalmers. It appeared as a

weekly edition. During the next 84 years several attempts were

made to found rival organs, but none lasted for long. It was

not until 1832 that a serious competitor came along in the form

of the Aberdeen Herald and General Advertiser (but generally

known by the truncated title of the “Herald”). It was created

by the fusion of the Aberdeen Gleaner and the Chronicle. Fierce

competition for readers commenced between the Aberdeen Journal

and its new rival. They were briefly joined by other would-be

competitors, the most notable of which was the North of Scotland

Gazette (NSG) in 1845 but none of the newcomers proved to be

enduring titles. In 1841 Aberdeen, with a population of 67,000,

had four weekly newspapers, the Journal

(2300 circulation), Herald 2050, Banner 1200 and Constitutional

500. The Banner (terminated 1851) and the Constitutional soon

met their demise in this clearly overcrowded newsprint market.

The Aberdeen Herald and General Advertiser

This newspaper was created in 1832 by the

merger of the Aberdeen Gleaner and the Chronicle. Politically,

the Herald supported the Whigs. Its first editor was John

Powers, but he was replaced by James Adam, who was characterised

by being politically radical and unafraid to criticise religious

views, especially those of ministers of the Established Church,

which he did at the time of the Disruption in 1843. He

supported the Chartists, a movement dedicated to gaining

political rights for the working classes, which was active

between 1838 and 1848. The demands in their charter were

universal male suffrage, secret ballots, equal-sized electoral

districts, abolition of property qualifications for MPs, payment

of MPs and annual parliaments. At this time there was a strong

Total Abstinence movement in Aberdeen, which was entrenched in

the evangelical Presbyterian churches. James Adam was

unsympathetic to abstinence and used to meet with his cronies in

the Lemon Tree tavern.

Ministers of Religion were often outraged

by the content of the Aberdeen Herald and, famously in 1841,

James Adam retaliated by seeking damages from Rev John

Allan. It was claimed that Rev Allan had used the words, “There

is an infidel weekly publication or paper in Aberdeen edited by

an infidel, an infidel villain, a blasphemous villain, a low

villain, a hired agent for attacking the clergy, an agent of the

devil, a Satanic agent.” William McCombie (1809) had been a

supporter of the Aberdeen Herald during the 1840s because of its

Liberalism, but his views on the newspaper must have been

somewhat ambivalent. He was in tune with its political stance

but must have been uncomfortable with its irreligious

tone. James Macdonell (a sometime reporter on the Free Press

– see below), said of Adam “If

he wants that free and easy air respecting religion and that

desperately witty manner, which are characteristics of Mr A’s

effusions, it has a depth of meaning and a moral suggestiveness

which to them is utterly foreign.” He

further described James Adam as follows, quoting from Hazlitt, “he

is an honest man with a total want of principle”. Adam remained

as editor of the Herald until 1862 when he was succeeded by

Archibald Gillies.

The North of Scotland Gazette

The prospectus for a

new title, the North of Scotland Gazette (NSG), was published in

early 1845, which proposed a four-page, large-size, weekly

newspaper with content split equally between advertisements and

commercial intelligence on the one hand, and local and general

news on the other. It was divided into two sections, the

advertisements to be distributed free and the news and

commercial section available by subscription. The annual fee

was £5 for which customers would receive both sections. It

described its own policy in the following terms. “In so far as

general politics are concerned, the Gazette preserves strict

neutrality; but its columns exhibit a concise yet comprehensive

view of the varied and complicated movements of the whole

political system. Unbiassed by party , it gives weekly a

faithful and impartial record of Domestic and Foreign Affairs, -

the sole aim being to afford every necessary information to the

Politician to secure the countenance and patronage of the Man of

Business, to interest the Farmer as well as the Proprietor of

the Soil, to instruct and amuse the more General Reader, and in

every way to make the Gazette a Complete Family Newspaper.” It

was proposed that publication would start as soon as 700

subscriptions had been secured and this point seems to have been

reached about the end of March 1845 as the first edition

appeared on 1 April of that year. The publisher / proprietor

was William Bennett, a printer based at 42 Castle Street,

Aberdeen.

Almost immediately the NSG got into a

stooshie (disagreement) with two of its rivals, the John

O’Groats Journal and the Aberdeen Herald, over the appropriation

of paragraphs from those newspapers without acknowledgement, and

the NSG then seemed to labour to become economically

viable. Another rival, the Banner, the newspaper of the Free

Church, was also struggling for survival at about this time. By

1847 the NSG had acquired Rev JH Wilson as its editor. He was a

vice-president of the Total Abstinence Society. Rev Wilson

continued in this role until at least 1851, though after that

date he was no longer listed as having a connection with the NSG

in the Post Office Directory. He was succeeded by David

Macallan (see below), one of the newspaper’s proprietors, until

1853. The

great significance of the NSG was that it was taken over by a

partnership of George King,

William McCombie (1809) and David Macallan in 1849. In

political character it became a “decided advocate of liberalism

and voluntaryism”. As part of the change in editorial policy,

the editor of the NSG, JH Wilson left the paper to become the

Minister of the Albion Street Chapel, Aberdeen. He departed

with a £50 “golden goodbye” from the proprietors. The new

owners clearly had their own political and social agenda and

installed William McCombie (1809) as the editor of the new paper

in 1853. He supported disestablishment of the Church of

Scotland. Two subjects on which the Free Press campaigned

consistently were universal suffrage and the expansion of

secular education.

So, what was the background of the new owners

(other than William McCombie (1809)) and what did they have in

common?

David Macallan, a Baptist, was the son of

an Aberdeen ship’s captain, born about 1793, who himself took up

the trade of upholsterer, initially at 1 Martins Lane, but from

1835 at Strawberry Bank, in the firm of Allan and Macallan. He

resigned from his business partnership in 1848 after the firm

received a Royal Warrant and he felt that, on principle, he

could not sign an oath of allegiance. David Macallan seems to

have been reasonably well-off. When he died in 1858, his

personal estate was stated at between £1,500 and £2,000

(£162,000 - £216,000 in 2018 money). The value of his share in

the newspaper co-partnery with George King and William McCombie

was estimated at the time at £53 (£5,725 in 2018 money). David

Macallan devoted much of his time to public life. He was a town

councillor for many years and took a strong interest in the

welfare of the poor, for example, contributing to the West

Aberdeen Coal Fund, the Public Soup Kitchen, the Albion Street

Mission, the House of Refuge (for destitute persons), the

Aberdeen Lodging House Association, the Benevolent

Fund for Female Domestic Servants while labouring under

sickness, the Industrial School Association and the Aberdeen

Property Investment Company. This last body was a private

sector vehicle set up to build adequate houses for the poor,

which was also supported by George King. David Macallan was a

deeply religious man and

a member of the Auxiliary Religious Tract Society.

George King was born at Slains on the

north east coast of Aberdeenshire in 1797. He was the son of a

shoemaker, leather merchant and currier and this line of

business seemed to be his destiny too but, by 1827, he and his

brother Charles, who was born in 1800, had moved to

Aberdeen. Charles set up as a furnishing tailor and followed

this business until he retired about 1856. George was initially

described as a book agent but from 1828 this changed to

bookseller, often with additions to that enduring

title. Between 1831 and 1842 his business was also as a

stationer and between 1829 and 1842 the shop was also the

Depository of the Tract and Aberdeen Auxiliary Bible

Societies. In 1843, on his brother Robert joining him, the

trading name changed to George and Robert King (G&R) and the

Depository function lapsed. In 1853 another brother Arthur

establishing his printing business (see below) and printing was

dropped by G&R. Although Robert had died in 1845, his name was

retained in the title of the business until about 1864. By 1864

George King too had retired and the business was passed on to

another bookseller, James Murray.

George King’s bookshop, stationery and

publishing business in St Nicholas Street was well known to

Aberdonians with religious and social interests. In addition to

new books with a religious theme, pamphlets and sermons, he

frequently advertised books of poetry and lists of second-hand

books which had been passed to him for disposal. George King

was the publisher, in 1845, of “Memoirs of Alexander Bethune” by

William McCombie (see above). G&R were also the publishers of

Christian Sociology by the Rev John Peden Bell in 1853. Bell

was a close friend of William McCombie (1809). In the social

sphere, George King was a thorough-going liberal and

abstainer. In 1847 he was the signatory of a letter to Lord

Provost Blaikie objecting to the provision of intoxicating

liquor at funerals. He subscribed to good causes such as the

West Aberdeen Coal Fund, the Aberdeen School of Industry for

Girls, the relief of the unemployed in the Aberdeen suburb of

Woodside, the unemployed weavers in Lancashire in 1862, the

Boys’ School of Industry and the Model Lodging House. He was

involved in the setting up of the Improved

House Accommodation Company Ltd in 1859, whose objective was the

provision of decent accommodation for the working

classes. Another housing initiative to receive his support was

the Aberdeen Property Investment Company which appeared to

function like a building society in taking deposits for interest

and providing loans to members to build their own heritable

properties. He

was a member of Captain Dingwall-Fordyce’s (Liberal) election

committee in 1847. At the General Election of 1852 he was a

member of the committee supporting Mr Thomson who stood for

election to the constituency of the City of Aberdeen on a

platform of “progressive reform” and in 1855 he supported the

candidacy of Colonel Sykes. George King was for many years a

member, then the chairman, of the Old Machar Parochial Board

where he took a particular interest in the relief of the

poor. He wrote a tract “Modern

Pauperism and the Scottish Poor Laws” in 1871 and at one time he

was chairman of the Old Machar Poorhouse. In

religion George King was a Congregationalist and was a trustee

of the Congregational Chapel in George Street. He was heavily

involved in the building of a new Congregational Chapel in

Belmont Street in 1864 and he was also a member of the London

Missionary Society.

Unsurprisingly, George King was opposed to

slavery in America and was instrumental, along with William

McCombie (1809) and his cousin James Bain McCombie, in

establishing the Freedman’s Aid Society in 1865. The purpose of

this body was to promote the work of an anti-slavery delegation

from America to the religious community in Aberdeen. In

addition to his main business of bookselling, he had other

business interests from time to time, such as partner in a

flesher business and he was a shareholder in the Aberdeen Music

Hall Ltd and various other companies. His non-business

interests included the Volunteer Artillery and Rifle Association

and antiquarian studies (he was elected a Fellow of the Society

of Scottish Antiquaries in 1870). George King was also a member

of the Spalding Club, which was devoted to antiquarian studies

in Aberdeenshire. When he died in 1872, George King left a

personal estate of £3,821 (about £428,000 in 2018 money). He

also owned number 19, Carden Place, an upmarket residential

street in Aberdeen.

Robert King was born in 1811 in Banff. He

started a bookshop and printing business in Peterhead but, in

1843, Robert went into partnership with brother George, as

George and Robert King, based in St Nicholas Street, Aberdeen,

with a separate printing works in Golden Square and, from 1849,

in Flourmill Lane. Robert was also an accomplished writer but,

sadly, died in 1845. Shortly before his demise, G&R published “The

Covenanters in the North”, Robert’s best-known work. (Robert’s

son, also George, became a distinguished botanist and doctor in

the Indian Army, who worked on the extraction of quinine (for

treating malaria) from the Chinchona tree, and the distribution

of the drug throughout India via the postal service, for which

he received several honours).

Arthur King was another brother of George,

Charles and Robert, though the youngest of the four, having been

born at Peterhead in 1815. About 1835 he too joined the

printing trade and served a seven-year apprenticeship as a

compositor, presumably with Robert King in Peterhead. After

completing his training, Arthur worked for a short while for the

Aberdeen Banner and on his own account before setting up as a

printer by 1843. At the 1851 Census of Scotland, Arthur’s trade

was described as printer and compositor.

According to the obituary written by James

Macdonell, “For

many years he (William McCombie (1809)) had strongly felt

the need of a local newspaper which should be at once decidedly

Liberal and earnestly Christian. The need was the more

impressive because the Aberdeen Herald was then edited by a very

clever and reckless man (James Adam – see above) who

constantly poured ridicule on all religious earnestness and

whose writing was made formidable by its broad humour and its

force of style.

The first stage in the process of creating an

alternative journalistic organ had been the purchase of the

struggling NSG and the change of editorial direction in

1849. The second stage had been the replacement of the NSG with

a new publication, the Aberdeen Free Press and North of Scotland

Review (generally abbreviated to “Free Press”) in 1853. This

title was modified in 1855 to “Aberdeen Free Press, Peterhead,

Fraserburgh and Buchan News and North of Scotland Advertiser”,

though this title change was reversed in 1869. The owners of

the Free Press were David Macallan, William McCombie, George

King and Arthur King. The following abstract from the Aberdeen

Herald in March 1853 is the announcement by Arthur King of the

impending change. “Arthur King and Co, Printers Broad Street

respectfully intimate to the public that in place of the North

of Scotland Gazette which in consequence of a partial change in

the proprietary (presumably the admission of Arthur King to

the partnership) is to be discontinued, they will commence

publishing on 6th May ensuing in a considerably

enlarged size and under the same editorial superintendence “The

Aberdeen Free Press and North of Scotland Review”. The Free

Press will be conducted on the same general principles as the

“North of Scotland Gazette” has been for the last four years.”

In June 1852 Arthur King placed the

following notice in the Aberdeen Journal. “Arthur

King, Printer, begs respectfully to intimate to the inhabitants

of Aberdeen and its vicinity that he has commenced commercial

business in the above line in those central premises 2 ½ Broad

Street (second floor) where he will devote his attention to

general printing including Book, Pamphlet and Jobbing work.” He

was the sole partner in the company. Arthur

King’s business was much more extensive that the publication of

the Free Press. He developed a high reputation as a book

printer and became the printer for the Aberdeen University

Press. But in 1869 he both moved premises and ceased to be the

printer and publisher of the newspaper. “Arthur King & Co

Printers beg to intimate that with a view to secure extended

accommodation for their largely increased general printing

business they have taken a lease of those premises Clark’s

Court, Upperkirkgate, to which they will remove at the end of

the month of July ensuing. Ceasing by mutual agreement its

connection with the Aberdeen Free Press.” What caused the split

with his other partners is presently unclear. The Free Press

then undertook its own printing of the newspaper. However,

successful though he was as a printer Arthur ran into trouble

three years later when he overtraded and ran out of capital. He

had to grant a trust deed over his assets in favour of his

creditors. The business was put up for sale and then acquired

by the company’s foreman, William McKenzie and continued in a

successful way. In marked contrast to his brother George,

Arthur King seems to have been almost exclusively focussed on

his business and not much interested in civic or social

matters. Arthur died in 1882.

William McCombie (1809)’s editorship of

the Free Press