|

BY WALTER A. SMITH.

DEAR MR EDITOR,—YOU remind me of what was, I fear,

rather a rash promise I made last year, to send you another paper :for our

Journal; I should be very glad to fulfil that promise, and must: e'en .try

toldo my little best accordingly; and truly. I find on sitting down

deliberately to my task that the sooner. I. set about it. the better. And

for this reason, Sir. I observe that. tinder your energetic editorship the

able pens following upon the certainly not less able legs: (not to speak of

breech-splitting strides") of many of our worthy members are rapidly:

covering in your pages most of our grand old hill country that I, a steady

going hillsman (I hardly dare call myself a mountaineer), at present know I

could tell of climbs and rambles on Ben Aulder, by SuiIven, on.

Scuir-na-Gillean, on Ben-y-Gloe, on the hills above the lovely and now

celebrated Glen Doll, in the: wonderfully picturesque region of upper Glen

Nevis, and; I daresay, many more. But you yourself Mr Editor, our esteemed

President, and amongst others of course the ubiquitous Munro, have already,

said much of these places. Still there is, to me at any rate, a very

interesting and charming subject connected with the mountain scenery of

Scotland that has not as yet been much touched upon in the journal, although

Mr Watt well described the "Corryarrick" in the January number, and Mr Dewar

referred to various "crossings" from Balquhidder, amongst them the

interesting Bealach a Chonnaidh, in September last. Mr Munro also, I notice,

mentions the famous "Bealach" from Glen Aifric to Loch Duich (well I

remember the glories of it!), and one or two others in that district. The

word "Bealach," I confess, has a great attraction to me; and I have rarely

been across a Highland pass, either of high or low degree, whether it be

through the bleak moor of Drumouchter in the rattling train, or scrambling

by a rocky ledge in the cleft of a riven crag, but what I have felt an

excited eagerness and expectancy as to what is to be seen and done when I

get to the other side! I trust, Sir, you appreciate the particular frame of

mind I speak of? Is it not often almost as fine a thing in its way as

gaining the top of a Ben? One of my more recent experiences of the kind was

when Charles Macpherson and I pushed our way one day last July round from

the back of Ben Aulder through that "fearsome" Bealach Dhu at the wild west

side of the mountain, down towards Loch Pattach, amidst mingled rain, wind,

mist, and sunshine! I can assure you, Sir, we found it quite exciting. And

the mention of our good friend's name reminds me of a long walk we had

together in 1887; and it occurs to me that perhaps a few notes regarding the

"hill crossings" we then effected may be of some little interest or use to

our members.

We met by appointment at Fort-William, and first left

the main road at Fassfern on the north shore of Loch Eu, five miles west of

Corpach, intending to push on to Inverie, on Loch Nevis, by a route

described in Anderson's old "Guide to the Highlands." The route crosses four

distinct high mountain passes. The first is from the head of the north-west

branch of the Suileag stream, up above whose north side, on the slope of the

big round Meal Onfhaidh hill, the path is fairly well marked, more so at the

actual "col" as is usual in these Scotch hill passes, the whole occasional

traffic of centuries being there confined to almost one possible way

through. The view opening away to the west, across Glen Fionn, to which we

descended, was a striking panorama of mountain peaks. The crossing of the

Fionn was our first difficulty and perhaps naturally so, as it was our first

entry into deer forest. The gradually vanishing path took us to an ancient

wooden bridge, but of so unstable, rickety, and long unused appearance that

we dared not venture our lives upon it. We therefore forded at foot of the

gully over which it went, and ascended the east side of the Choire Reidh

Water, which flows down through a delightful green pastoral valley

apparently given wholly up to deer. The next crossing was out of this glen,

by the high steep "Panting Pass" (2,000 ft.), west of the Gulvain mountain,

and down to the head of Glen Camaraidh. To top of this fine pass the track

was fairly visible, but there it seemed to come to an end. A little way east

was the fatal slope where the unfortunate young Earl of Dalkeith had met his

sad fate so recently. Far down the glen the head of Loch Arkaig glistened in

the sunshine. But not a sign of life around! Not even the cry of a grouse or

a curlew disturbed that immense and almost melancholy solitude. We steered

W.N.W., and descended to near the 1,000 feet level, and then climbed out of

Camaraidh and over to foot of Glen Pean. In this crossing we again come on

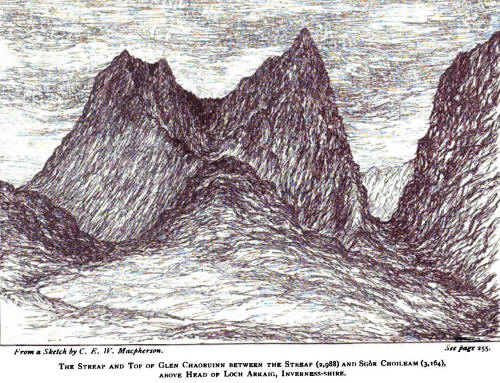

traces of our road, and have some most wonderfully picturesque views of the

strangely sharp and rugged "aiguilles" of Streap and Sgôr Choileam, two of

the most remarkably shaped hills in Scotland, near at hand to the west ; as

also of the higher Inverness-shire mountains in the north. In Glen Pean we

were away from deer among the sheep once more, and so we actually met a MAN,

who rather marvelled at our journey, but wished us good speed thereon! Then

in Glen Dessary more men, a sheep shearing, a score or so of collies, and a

substantial afternoon tea at the shepherd's house. (Oh, ye gods! these

scones and that butter! Even now, four years after, the grateful memory of

them is sweet.)

Glen Dessary is a straight and comparatively open

glen, with fine hills on either side, particularly to the north, and forms a

natural passage through the country to the west. There is, I believe, a path

out of it to the N.E., by Glen Kingie to Glen Garry. But the main exits are

to the west, through its double head, the most northerly one being by the

rugged pass known as "Mam-na-Cloich Airde" to Loch Nevis, through which

Prince Charlie wandered. Above this pass is the great isolated Peak of

Sgr-naCiche (3410 ft.), and in it. at the watershed, near the pathway are,

or were, three cairns marking where the lands of Knoydart, Locheil, and

Lovat meet. We, however, on this occasion took the higher and perhaps even

wilder pass more to the south, which leads over to the head of Loch Morar.

This is truly a most extraordinary narrow rocky cleft through the hills, and

ultimately the rough track creeps along the north shore of a little loch

with a big name (Lochan Gain Eamhaich!) at the base of a rugged cliff, and

descends to Kinlochrnorar. Loch Morar, recently ascertained to be the

deepest fresh-water lake in Scotland, is of surpassing beauty, and its head

is, perhaps, as remote and unfrequented a place as may be found in the

kingdom. It is deer forest here again, but Lord Lovat's gamekeeper, who

lived then (in 1887) in a solitary cottage at the water side, entertained us

hospitably for the night. He told us there was also a "grand pass" to

Kinlochmorar from the east, lower than the one we traversed, and farther

south, between the heads of Glen Pean and Glen Oban.

Our wanderings for the next three days, by rowing

boats and mountain roads, down Loch Morar, across Loch Nevis and Knoydart to

Loch Hourn and its magnificent mountains, and thence away east by Glen

Quoich, Glen Garry, and Fort Augustus, were full of beauty, interest, and

pedestrian adventure, but presented no very direct features of interest from

a "mountaineering" point of view. The next route taken, which it may be

valuable for the Club to have some record of, was our crossing from

Whitebridge Inn on the old Stratherrick road, a few miles S.W. of Foyers on

Loch Ness, to Freeburn Inn on the Findhorn. This was a long day's march. Up

the lovely birch-clad Vale of Killean, and for a mile and three-quarters

beyond the picturesque loch of the same name, with its two comfortable

shooting-lodges (Lord Lovat's), there is a fairly good driving road. Thence

a path leads away east up the south side of the straight shelving Glen

Markie to near its head, where the stream comes down a fall from the north

almost at an acute angle to the main glen. Leaving the fall on the left, the

track—occasionally obscure—climbs higher E.N.E., and skirts above a curious

little cliff overhanging the boggy watershed, and descends gradually over a

rough slope of elevated moor, keeping a subsidiary tributary of the Eskin

(as the north-western higher stream of the long Findhorn river is called) on

the right. Looking down this moor the old stony track is plainly visible;

and a good view is obtained to the S.E. across the great high bleak

shoulders and plateaus of the Monaghlea Mountains. [The highest point of

this great range is Cairn Mairg (3,087) ft., six miles due south of the

above pass. It is a good climb to Cairn Dearg and Cairn Mairg up Glen Calder

from Newtonmore in Strathspey. On two occasions in recent years I have had

superb views---- especially to the west—from these summits.] Descending the

Eskin, keeping above the water on its north side, we reached the main valley

of the Findhorn at the bothy of Dalveg, whence there is now a driving road

all the way to Freeburn Inn, on the old coach road to Inverness from

Aviemore. It was a pleasant walk down the glen in the soft evening light,

the encircling hills being well shaped and beautifully coloured, and the

woods of Glen Mazeran and Dalmigavie added a sylvan charm to the scene. We

did not find the inn at Freeburn a very cheery or attractive residence, and

left it early next day (a lovely Highland Sabbath morn, I remember), and

walked down the high road to Aviemore and Lynwilg Inn, by the Slochmuick

Pass and Carr Bridge, the route by which the new direct railway to Inverness

is now being made. This road commands a beautiful and comprehensive view of

our grand old friends the Cairngorms, whose rugged massive buttresses we

scaled next day by the familiar Lang Ghru and Glen Derry route. What

infinite romance and grandeur there is about that wild rough passage by the

" Wells of Dee"! But if I once let myself begin to speak about the

Cairngorms I may go on for pages, so I shall merely mention that we got

comfortably over to Braemar. The following day was our last on this occasion

among the mountains, and it was devoted to the crossing to Clova, in

Forfarshire, by Glen Callater and the heights of Fafernie to the exquisitely

beautiful Glen Doll. It was a glorious evening as we descended into the

rocky ravine at the head of the glen. The splash and foam of waterfalls

invited us down the winding path among the rocks, past the lonelyruin of

"Jock's Shieling" to the top ofthesteep zigzag of "Jock's Road," leading

deeper still into the glen. (Who was that mysterious "Jock?" Some say a

notable thief and never in days gone by!) The setting sun lit up the bold

shapely crags and corries of Craig Maud and Craig Rennett, and penetrated

with warm shafts of light into the cool recesses of Corry Fee. The brilliant

green for which the hillsides and glens of Clova are so famous was toned to

a quiet softness, and all nature seemed to speak of peace and rest. The wild

mountains and moors were left above and behind us. The quiet, sheltering,

lovely valley lay below and in front. Our long journey was over, but we had

achieved our work. We had crossed Scotland almost from sea to sea (from Loch

Hourn to Dundee!) at her broadest and most mountainous part, and chiefly

with our feet upon the rock and heather. It was a most interesting and

delightful excursion, and I trust this brief record of it may not prove very

wearisome to your readers.—I am, &c.

W.A.S.

|