|

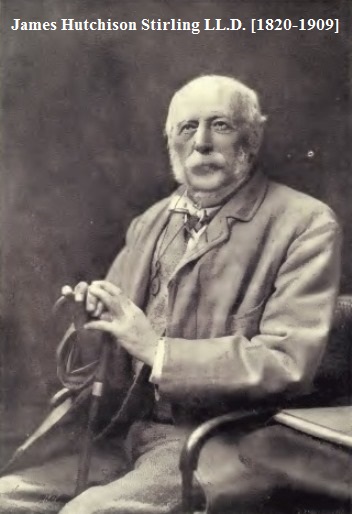

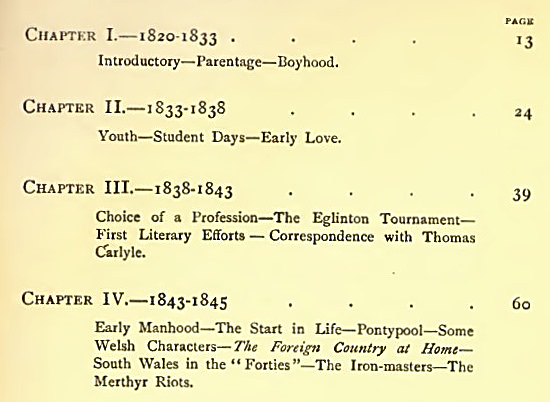

James

Hutchison Stirling was born on 22 June 1820, the fifth

son of William Stirling, craftsman, of Glasgow. He first

matriculated at the University of Glasgow in 1833 at the

age of 13, and followed a full Arts curriculum (1833

Latin, 1834 Greek, 1835 Greek, 1836 Logic, 1837 Ethics)

before continuing on to medical studies under Harry

Rainy (1792-1874), who became a professor of Medical

Jurisprudence in the Faculty of Medicine in 1841, and Dr

Buchanan.

Early in life he showed a leaning toward philosophical

studies, and in 1838 the professor of moral philosophy

gave him as a subject for a thesis, St Anselm's argument

in the Proslogion for the existence of God. With the

fine carelessness of youth Stirling is said to have

pronounced this argument a sophism, although in later

life he came to regard it as "the first word of modern

philosophy."' He did not obtain a degree in either Arts

or Medicine from the University of Glasgow. He became a

Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

in 1842 and a Fellow in 1860. In 1843 he settled in

practice at Hirwain, Glamorganshire, and later he moved

to Glyn Neath. For a while he was a surgeon to the

Hirwain and other iron and coal works in South Wales.

Upon the death of his father in 1851 Stirling retired

from practice and went abroad. He studied firstly in

Paris under Dumas, Orfilia and Milne Edwards. In 1854 he

moved to Germany, where he resumed his philosophical

research of Kant and Hegel. In 1857 he returned home and

turned to writing books on philosophy. His publications

include: The Secret of Hegel: being the Hegelian system

in origin, principle, form, and matter, 1865;

Materialism in relation to the study of medicine: an

address to medical students, 1868; Lectures on the

philosophy of law, 1873; Text-book to Kant: the critique

of pure reason : aesthetic, categories, schematism:

translation, reproduction, commentary, index, with

biographical sketch, 1881; Darwinianism: workmen and

work, 1894; and What is thought?: or, The problem of

philosophy by way of a general conclusion so far, 1900.

He was a Foreign Member of the Philosophical Society of

Berlin and delivered the first Gifford Lecture Series at

the University of Edinburgh on Philosophy and Theology

in 1888-1890. He was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of

Law from the University of Edinburgh in 1867, and one

from the University of Glasgow in 1901. James Hutchison

Stirling died at the age of 89 on the 19th March 1909.

He left an estate of c £10,000 to his four daughters,

Jessie Jane Armstrong, wife of the Rev Robert Armstrong

of Glasgow, and Amelia, Florence and Lucy, who were all

three living at the parental home in Edinburgh.

Edinburgh University still awards an annual James

Hutchison Stirling Prize to the best student studying

for the degree of MA with Honours in Philosophy who has

attended a second course in Philosophy, but who is not

yet in his or her final year.

Sources: Glasgow University Archives student records,

Medical Directory 1898, The Lancet, March 27 1909,

p.248, Calendars of Confirmation.

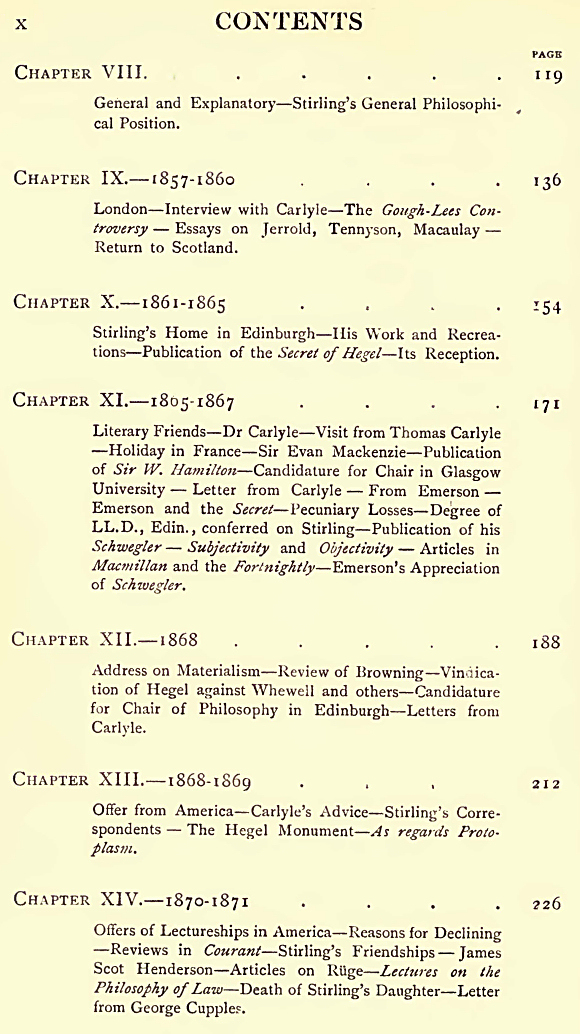

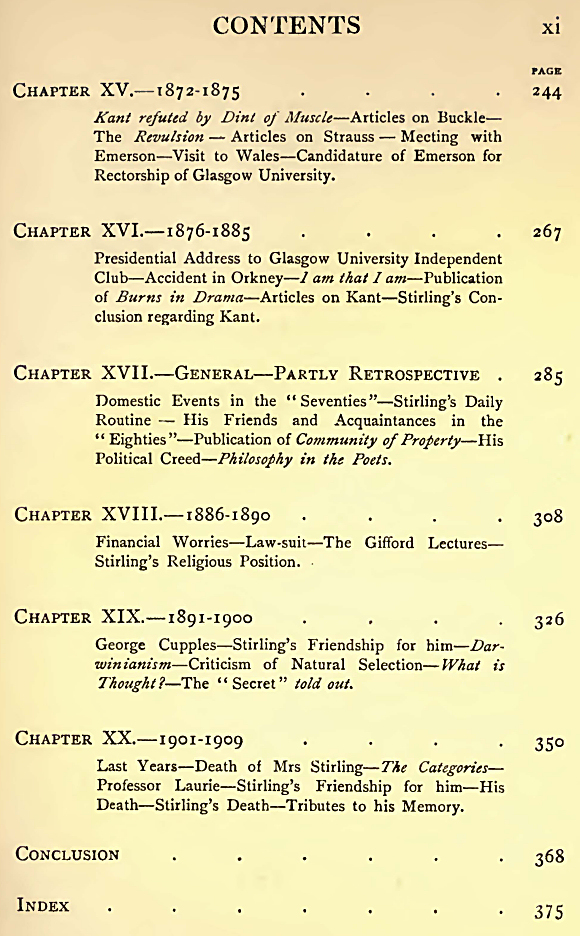

PREFACE

It is my

privilege to have been invited to write a few lines of

preface to the life of one whom I knew well and admired

greatly. James Hutchison Stirling was a man of genius,

rugged and uncontrollable, yet genius that could not be

mistaken for anything less. I knew him first when I was

a student at the University, and I saw him from time to

time until nearly the period of his death. The man is

mirrored in his books, and above all in the greatest of

his books, “The Secret of Hegel.” To come under the sway

of the “Secret” one must have oneself worked hard.

Stirling made the meaning as plain as that meaning could

be made. But to penetrate into the inmost significance

of Reality can under no circumstances be possible

without the severest effort at concentration, and this

the book demands. But when the effort has been made,

and, it may be after several struggles, success has

come, the reward follows. I doubt whether a more

remarkable piece of exposition has ever been

accomplished in our language. It is marvellous that,

working at the time he did, without the help of a single

worker in the English language who had thrown light on

what Hegel really taught, Stirling should have produced

the book he did. No one since his time has got further,

possibly no one as far. He penetrated into the inmost

essence of the Hegelian system as none but a man of

genius could have done, and his work remains unrivalled

to this day. His exposition is charged with meaning, and

its flow is that of a torrent. No wonder that he held

Carlyle in reverence. In different forms the two men

applied to different subject-matters the same gift. Both

were expositors, but expositors of a genius that made

their teaching new and original. “ Sartor Resartus ” and

“ The Secret of Hegel ” may both be fairly said to have

been epoch-making books. Carlyle wrote for the many,

Stirling for the very few, and that was the main

difference between them. The concentrated work which

each bestowed on what he produced was of the order that

is colossal.

It is only by grappling with “The Secret of Hegel ” that

one can realise the extent of its author’s power and

penetration. Through long years of study he mastered the

meaning of that most difficult and most rewarding of

modern writers on philosophy. At the end the result he

had reached was returned in a torrent; in language the

force and picturesqueness of which were only matched by

the conviction every sentence breathed forth. The book

embodies a result which is likely to be enduring. It

will hardly be superseded, for it has the quality of the

work of genius. Along the road it has travelled one

cannot get any further.

Haldane of

Cloan.

London, 3ra November 1911

Author's

Note

In one of

Stirling’s articles on Kant, to which allusion is made

in the following pages, this remark occurs: “If the key

has been found for the casket of Hegel, and its contents

described, it is quite certain that the public has never

yet seriously set itself to apply this key or examine

these contents. Something to stimulate or assist seems

still to be wanting.” In the present volume it is hoped

that at least a step has been taken towards supplying

what is wanting. It has been sought to “ stimulate ” by

laying before the public the record of a life-long

devotion to the study and development of the Hegelian

philosophy, a life-long conviction of its profound value

to humanity. It has been attempted to “ assist ” by

showing that, though it is only the earnest student of

philosophy who can ever hope to penetrate to the centre

of the Hegelian system, Hegel has yet something to offer

to every thoughtful reader. Throughout the later portion

of the present book—especially in Chapter VIII., and in

those chapters which deal with Stirling’s various

works—attempts have been made to indicate, in terms

intelligible to a technically uninitiated reader,

Stirling’s general philosophical position, and the

nature of the service which he and thinkers such as he

have rendered to mankind.

It is impossible to let these pages go to press without

tendering thanks to those who, in various ways, have

helped in the task of preparing them— to Mr Alexander

Carlyle and Mr Walter Copeland Jerrold for kind

permission to make use of valuable letters from Thomas

Carlyle and Douglas Jerrold respectively; to Mr W.

Hale-White, Mr Holcomb Ingleby, the Rev. John Snaith,

Emeritus Professor Campbell Fraser, and the family of

the late Professor S. S. Laurie, for kindly lending

important letters written by the subject of this memoir,

and to Mr Murdoch for the excellent photograph of the

philosophers study, from which one of the illustrations

has been taken. Lastly, special thanks are due to Lord

Haldane, who, in the midst of the innumerable public

claims upon him, has shown that his interest in the

higher philosophy is as deep as ever by writing the

appreciative and vivid estimate of Stirling which forms

the Preface to the present book.

A. H. S.

Edinburgh, November 1911.

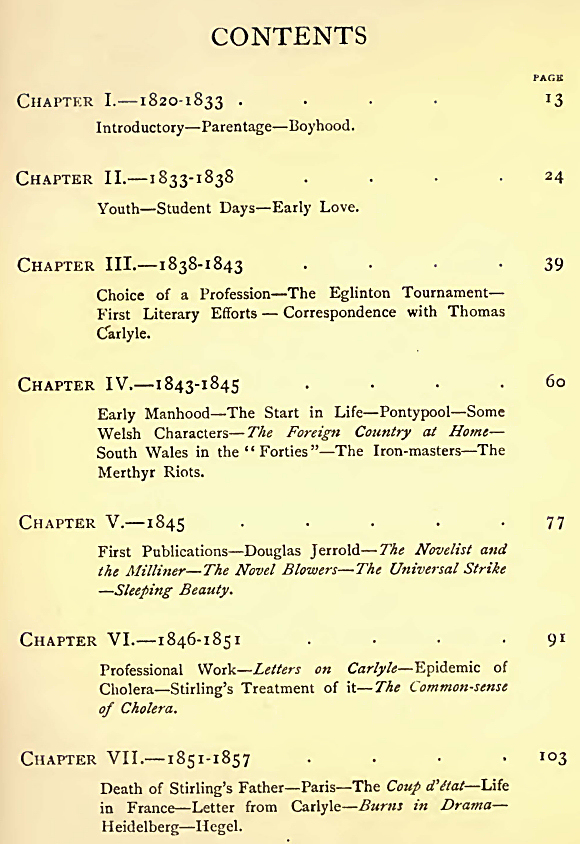

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

Section 4

Section 5

Final Section

Philosophy and Theology

His 20 lecture series

The

Secret of Hegel

Being the Hegelian System in Origin, Principle Form and

Matter

The

Categories

|