|

"He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall

never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His

judgment seat;

Oh be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my

feet

Our God is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a

glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me;

As He died to make

men holy, let us die to make men free,

Our God is marching on."

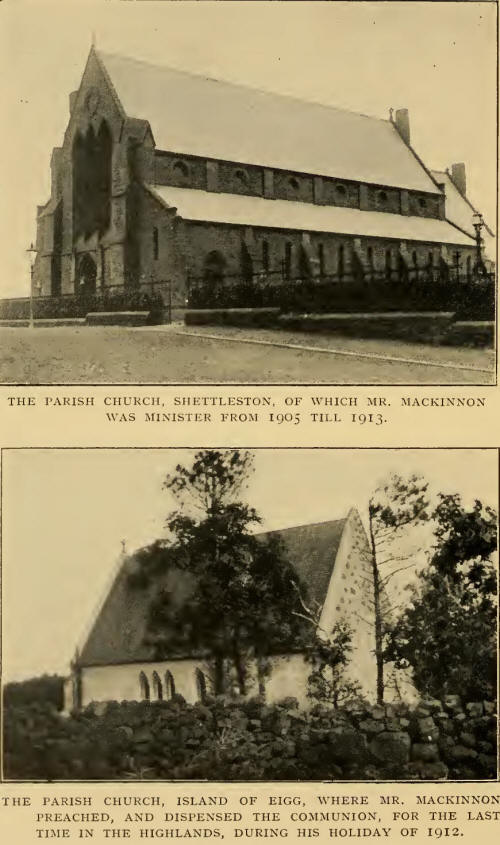

THE call to Shettleston was clear and unmistakable, and the Highland

minister had a most cordial reception from the Lowland people. The

Induction took place on the thirteenth of April, 1905; and in the evening

there was the usual congregational social meeting for welcome and

presentation of robes. The evening meeting was a most enjoyable one, and

all the speeches were excellent ; but strangely enough, just as the robes

were placed on the minister's shoulders, the writer found herself

struggling fiercely with a sudden lump in the throat and vainly trying to

keep back tears which would not be stayed. The Minister never knew of

this, and often we wonder now, did anything whisper it was to be the last

robing but one? When, late that night, we retired to rest in a Glasgow

hotel, we asked if it was true that there was a debt of

£2,000 on the church hall. The Minister knew nothing of it. We had just

come from the building of a hall in Campbeltown; if it did seem a little

hard, we remembered that the only way to deal with difficulties was to

overcome them, so we laid ourselves down and slept, knowing that the way

was all marked out, and that our part was to follow the Guide.

In a letter to the Secretary of the Vacancy Committee,

written from Campbeltown, and dated February 25, 1905, Mr. Mackinnon

says—"I am deeply sensible of the responsibility which Thursday's vote has

imposed upon me, and I do intend to prove myself worthy of the confidence

which has thus been placed in me." We all know how the vow was kept.

The children had been sent to Crieff to be out of the

confusion and discomfort of the "flitting," and it was not until they were

brought back that the strange manse could be called "home." We were glad

at least that it was surrounded by green fields, and we had the kindest of

neighbours in Dr. Hill, of Barlanark, and his niece Miss Grahame.

But long before the manse could be got into order, the

Minister was in harness, visiting with his elders and fulfilling many

engagements both inside and outside of the parish. The congregation at

this time numbered 1,130 members; in November, 1912, the number of

communicants at Mr. Mackinnon's last Communion service was 1,780. At the

first and last Communion of the Shettleston ministry, the assisting

minister was Mr. Strang, of the Castlehill Church, Campbeltown, who had

also baptised both Mr. Mackinnon's Sons.

It was not long before we discovered that Shettleston

was not to be one whit behind Campbeltown in genuine friendliness and

kindness towards its minister, and those belonging to him. The change was

never once regretted, even when the battle was at its fiercest; for a

Herculean task lay in the ministerial work of those eight years.

It was whispered about a good deal after we came, that

the people of Shettleston Parish Church "do not give." Now, without

staying to inquire whether there were very many distinctly Shettleston

people amongst us, the ordinary observer could not fail to notice that

they were continually giving to one cause or another. The first appeal

made by the Minister from the pulpit on behalf of a Glasgow church was

responded to with ready generosity. Others followed, and were treated in

much the same way. The two quod sacra parishes at Tollcross and Carntyne

were in need of help, which was given cheerfully and without any

unnecessary delay, notwithstanding the fact that the Parish Church people

were themselves burdened with a debt of 2,000. The treasurer's financial

report never allowed us to forget that 600 at least was required annually

for the upkeep of the Church, and if, any year, more was required, or if,

owing to extraordinary circumstances, there was a deficit, it was always

made up by special effort.

It is true that at first the people seemed disinclined

to give to Foreign Missions, and it was a little hard to be told stonily

that "charity begins at home." But we hope to be able to show that a very

great change took place in this respect during the years of which we are

now writing.

The first two years in Shettleston were marked by

rather trying and continuous ill health in the manse. The Minister himself

kept well, and indeed seemed to enjoy better health than he had had in

Campeltown. But the children had much trouble, and the minister's wife

ailed sadly. Vivid recollections of the first year are those of lying

listening daily to the tinkle, tinkle of the bell on the doctor's horse as

it scampered up the avenue. We weathered it all, however, and struggled on

for a time. But the manse was difficult to work; there was no gas, and on

this account, and also because it was " so lonesome," servants could

scarcely be got to remain for any lengthened period. So many fires were

needed because of the cold and damp, and this meant hard work and sore

hands, and girls are surely not to be blamed if they seek out the houses

where the work is easiest. But we were as happy as possible, only it was

hard to see so little of Daddy, who was out frequently all day, and not in

until very late. Once he managed to come in at five o'clock, and we were

all so delighted. The children begged for a "tea party" in mother's room

to mark the occasion, and one of them said, "Now how happy we are!" "Yes,

sonny," said Daddy; "if mother would only keep well." Nothing clouded his

spirit so much as the knowledge that any of his own were suffering.

After this came the bazaar, held in Glasgow, for the

quo sacra church at Tollcross, to which a stall had been promised. Every

one gave what they could quite freely, and there were plenty of willing

helpers. But, as we all know, it is one thing to get together

contributions for such purposes, and quite another to dispose of them,

even at reduced prices. After three or four days going backwards and

forwards into town, each one wearily endeavouring to get rid of articles

which no human being required, or was ever meant to require, getting home

late at night over a long dark road in boisterous wind and drenching rain,

one begins to wonder if the cost of some things is not out of all

proportion to their actual value.

That year there was a deficit in the funds of the

congregation, and we had perforce to get up another sale of work. It was

most heartily supported, and was moreover the means of bringing together a

band of workers who were afterwards always in readiness for service. There

is something more than a merely subtle difference between a "Bazaar" and a

"Sale of Work." Methods are frequently adopted at the former which cannot,

or ought not, to be tolerated under the shadow and in the interests of a

Christian church.

The congregational treasurer had asked for 30 to meet

the shortage in the year's accounts, and out of the efforts of a few weeks

we were able to hand over £40. Numbers of new people were coming into the

church, and nothing helps strangers to feel more at home in a congregation

than to be asked to help in one or other of its many activities. How often

help comes from quarters from which it is least expected.

Every one was most anxious that a beginning should be

made in the effort to clear off the hall debt of £2,000, so that they

might then be able to build a new manse for their minister. But as yet the

way was not clear for this. From first to last there was much in the

Shettleston ministry to vex the spirit. There are men who would perhaps

not have minded very much, but this man was keenly sensitive and highly

strung. His mission as a minister was to win souls into Christ's Kingdom;

and the necessity laid upon him of continually boring for gold and silver

to extinguish debt and for other purposes was alien to his fine

spirituality. Yet never once was he heard to complain; he toiled early and

late, visited the sick in their homes and in hospitals, and shepherded his

rapidly increasing congregation with unwearied and loving care. As a

platform speaker he excelled, and was overwhelmed with requests from

societies and organisations in and around Glasgow, while from Sunday to

Sunday he preached with a freshness, a vigour, and an intensity which made

many marvel. But the secret was that he kept himself low at the feet of

God. "The love of Christ constrained him." This was the heart of all.

Yet it was well, and Thou hast said in season

As is the Master shall

the servant be;

Let me not subtly slide into the treason,

Seeking

an honour which they gave not Thee.

"Never at even, pillowed on a pleasure,

Sleep with the wings of

aspiration furled,

Hide the last mite of the forbidden treasure,

Keep for my joys a world within a world.

to Nay, but much rather let me late returning

Bruised of my brethren,

wounded from within,

Stoop with sad countenance and blushes burning,

Bitter with weariness and sick with sin.

Then as I weary me and long and languish,

Nowise availing from that

pain to part,

Desperate tides of the whole great world's anguish

Forced through the channels of a single heart.

Straight to Thy presence get me and reveal it,

Nothing ashamed of tears

upon Thy feet,

Show the sore wound, and beg Thine hand to heal it,

Pour Thee the bitter, pray Thee for the sweet.

Then with a ripple and a radiance through me,

Rise and be manifest,

O Morning Star,

Flow on my soul thou spirit

and renew me,

Fiji with Thyself, and Jet the rest be far.

"Safe to the hidden house of Thine abiding

Carry the weak knees and the

heart that faints,

Shield from the scorn, and cover from the chiding,

Give the world joy, but patience to the saints."

F. W. H. Myers.

The clouds which had continued to hang over the manse seemed to become

just then more threatening. Diphtheria had kept one of the boys in

isolation for weeks, and then, just as the anxiety was beginning to lift,

but before he was fully recovered, the minister's wife was stricken down

with serious illness. At the end of two days, and in the midst of much

consternation and alarm, an ambulance wagon was brought, and the Minister

went with his wife to a nursing home. How well we remember that journey.

It was a dreary winter afternoon; and at intervals as we rolled on through

the city there would be anxious questioning—"Were we all right?" "Was the

wagon shaking too much?" "Could he do anything?"

But all we wanted was that he should just "not go away." In the midst of

all the pain what hurt most was the spectacle of his anguish, and the

dread which only mothers know. The ambulance men were so kindly, assuring

us that they "always took people home again"; and as the stretcher was

about to be lifted in, one of them gave the order, "Shut your eyes now."

When we opened them again, there were four or five white-robed figures

hovering over us, and smiling reassuringly, as if there was nothing at all

wrong. We thought they might be angels, and found out afterwards that they

surely were! Then the Minister came in, but could not speak a word. After

a bit, "I'll come to-morrow; now, it's going to be all right now," and he

was gone. Presently he was sitting down to tea in the manse, with only his

little five-year-old son, as the other was still in

quarantine. Long afterwards we heard the story. The house was strangely

quiet ; the blessing had been asked, but the father did not begin, and the

child did not begin. And the father was having such a struggle with

himself that he could not see that the little heart was bursting. "Why

don't you go on, sonny? "he asked, and then caught sight of the downcast

face and tearful eyes. With one bound he was up, gathered his motherless

bairn to his heart, and together they sobbed.

"Now, sonny, it will be all right," said the Minister

after a bit, "please God mother will come back." "As one whom his mother

comforteth, so will I comfort you, saith the Lord."

The story of the following weeks can scarcely be told.

There was grave danger and sickening suspense: we were now of the number

of those "who in the morning say, would God it were night, and at night,

would God it were morning." But the burden over all was that there might

be no separation from those who needed us. It was then we realised the

depth of meaning in the beautiful little poem, entitled "The Mother," by

Katharine Tynan :-

I am the pillars of the house

The keystone of the

arch am I;

Take me away and roof and wall

Would fall to ruin

utterly.

* * *

I am the twist that holds together

The children in

its sacred ring,

Their knot of love from whose close tether

No lost

child goes a-wandering.

I am their wall against all danger,

Their door

against the wind and snow.

Thou whom a woman laid in a manger,

Take

me not till the children grow,"

For three long weeks the Minister missed no day in his coming, except the

Sundays ; so that the other patients, too, found themselves watching for

him. How he brightened up that room of pain for each of us ! Yet he spoke

very little, for all the while he was fighting down the shyness and

reserve he always felt in the presence of strangers. The very sight of him

in a sick-room was like a breeze from the Highland hills; he looked so

radiant always. And it falls to be told, too, how every day he carried

into the city from his manse a can of milk, because the effects of what

Robert Louis Stevenson called the "sweet whiff of chloroform" had turned

us against all else which was in reality but the

sick man's longing for the "water that is by the gate at Bethlehem."

And how shall we tell of the heaped-up kindnesses at this time, the

anxious and incessant inquiries of our dear Shettleston people? There was

no day when flowers and delicacies were not sent, until the room was like

a bower. And those who went daily to the manse because their hearts were

sore for the Minister, and kept things going; guiding the house and

looking to the little ones while he was out at work! Not until memory

leaves us can we forget any of these things.

Then quite suddenly one day the doctor said we might go home, and we

wondered greatly, for as yet there was not even strength to turn. Did he

mean that we might just as well be allowed to die at home. "Oh no!"

he exclaimed; it only meant that recovery would be prolonged and

tedious—a year or more perhaps—and we might wish to be spared needless

expense. So the ambulance was brought again, but this time the Minister's

face was beaming. What preparations had been made in the manse! Mother's

room had been got ready almost entirely by Daddy and

the boys, and how lovely it all looked. But we have no language in which

to express the deep, deep, thankful joy of restoration to loved ones.

There were yet other three weeks of extreme weakness,

during which no hired nurse could have done better, nor half so tenderly,

what the Minister did. He was so strong and gentle; so pleased and happy

because we thought him a "jewel of a nurse" ; so proud and glad when at

last his patient was able to walk from room to room. But he had another

patient, he said, who was alone and dying he feared, and could not take

the food which was being brought to her. Did we think we could manage to

make anything for her? So things were brought upstairs, something made

which might tempt a sick person, and sent down all wrapped up to keep it

warm. And the poor sufferer was so surprised, for she knew all about the

trouble in the manse, and told her minister next day that it was the only

food she had relished for a fortnight. Nothing made him so happy as to be

able to help people in these and other ways. Some one told us a little

while ago how he had gone to see a Highland lad in his lodgings in

Glasgow, and finding him ill in bed had lit the fire and tried to make the

room less dreary. It was just like him.

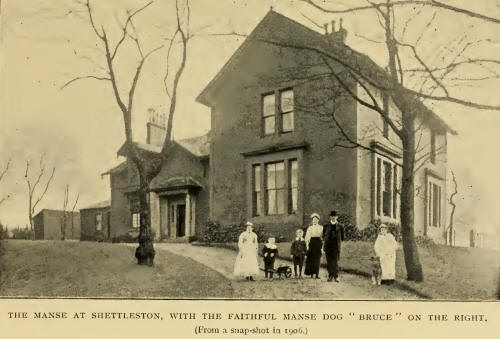

We can hardly go farther without introducing to our

readers "Bruce," the manse dog, and faithful, affectionate friend for

eight years. Bruce was a handsome black and tan collie, with a noble head,

soft liquid eyes, and a face full of intelligence. He had been most kindly

given to us, when he was only five weeks old, by a member of the

congregation, shortly after we came to Shettleston; and his upbringing was

a matter of great concern. As he grew older, his attachment to his master

was most touching; yet he knew quite well, although he had never been

told, that he must not follow the Minister when he went out; but he could

not be stayed from following every other member of the family. In the same

way he would lie perfectly still on the grass, and, with a look of abject

resignation, watch us walking off to church on Sundays. He had a welcome,

a little elephantine sometimes to be sure, for all who came to the manse,

especially for aunties, ministers, and assistant ministers! But he could

not tolerate bicycles or vehicles of any kind on the road leading past the

manse, and was frequently on this account guilty of glaring misconduct.

But was any member of the family ill? Then Bruce's place was beside the

sick-bed until restoration came. When he was taken on holiday with us, he

never failed to rebel vociferously against being put into the van of the

train. How his master laughed once at a far north railway station, to hear

the stationmaster, as he moved up and down the platform at six o'clock in

the morning, expostulating with delightful good humour, Noo, Bruce, if ye

dinna be qwyete, ye'll be pit 'oot." Alas, poor Bruce.

No one knew better than he did that there was something

very far wrong in the manse when, at the last, his master had to be taken

away in an ambulance. And although he was temporarily shut up and saw

nothing of what came and went afterwards, he whined and whined and sniffed

at the closed door of the quiet, quiet room. He never held up his head

after this, and when, on several occasions, he was missed from Buchanan

Gardens, he was always found lying prone on the cold doorstep of the

deserted manse, and within less than four months afterwards he sickened

and died. For days previously he had lain, unable even to lift his head,

but always answering with a deep groan, when we would say mournfully, "Oh,

poor Bruce." "Bruce broke his heart," said some One near by; and by a

strange coincidence, just at this very time we came upon the following

story:-

"Where in the whole world is there anything so

beautiful as devotion, whether of man to God, or man to man, or dumb

creature to his master? During 'the White Winter,' as any one may read in

Bob, Son of Battle, they found old Wrottsley, the squire's head shepherd,

lying one morning at Gill's foot, like a statue in its white bed, the snow

gently blowing about the venerable face, calm and beautiful in death. And

stretched upon his bosom, her master's hands, blue and stiff, still

clasped about her neck, his old dog Jess. She had huddled there, as a last

hope, to keep the dear dead master warm, her great heart riven, hoping

where there was no hope. That night she followed him to herd sheep in a

better land. 'Death from exposure,' Dingley, the vet., gave it; but, as

little McAdam, his eyes dimmer than their wont, declared huskily,' We ken

better, Wullie.'"

The time was now approaching when arrangements had to

be made to assist the members of the qud sacra church at Carntyne with

their bazaar in aid of endowment. Active help could not be given from the

manse on this occasion, but there were always willing and ready helpers,

and the work was carried through with great efficiency, and much

appreciation from the minister and congregation of the church at Carntyne.

Mr. Mackinnon's labours as Secretary of the Bridge of

Allan Convention were a delight to him. When he was sadly over-weighted,

as he too frequently was, the clerical work in connection with the

Convention would be handed over to others. The congestion of duties was

such, that no sooner would he have arrived at Bridge of Allan, than,

unfailingly, the manse telephone bell would ring, and with breathless

eagerness he would call out a list of things which he had forgotten, or

been unable to see to, and beg us to arrange for them. The standing wonder

was how he remembered so much! Yet no one at the Convention could sing

with more meaning or fuller realisation :-

"Like a river glorious

Is God's perfect peace,

Over all victorious

In its bright increase.

* * *

Not a surge of worry,

Not a shade of care,

Not a

blast of hurry

Touch the spirit there.

"Stayed upon Jehovah,

Hearts are fully blest

Finding, as He promised,

Perfect peace and rest."

In the spring of 1908 we accompanied him to the Irish

Convention, in the lovely lake-district of Killarney. There were many

earnest speakers, but our best memories of this Convention are—the

chairmanship of Mr. J. P. Crosbie, the Bible Readings of the Rev. J.

Stuart Holden, and an early morning address by Mr. Mackinnon on "The New

Song." We found our own notes of this latter only yesterday, and it seemed

like the reawakening of exquisite music (1) The Note of Redemption;" (2)

"The Note of Royally;" (3) "The Note of Consecration." The address itself

was like the morning song of birds, and was immediately followed by the

slow and impressive singing of—

"How I praise Thee, precious Saviour,

That Thy love

laid hold of me!

Thou hast saved and cleansed and filled me,

That I

might Thy channel be.

"Channels only, blessed Master,

But with all Thy wondrous power,

Flowing through us, Thou canst use us

Every day and every hour."

From Keswick Mr. Mackinnon always returned refreshed in spirit, and never

failed to "pass on" to those about him, and to his people on Sundays, the

helpful spiritual teaching he had himself received.

A very strong bond of unfeigned affection existed between him and the

Episcopal brethren with whom he was associated at Keswick. Mr. A. A. Head,

chairman of the Convention, says:-

"I had long cherished the deepest regard and personal affection for him;

and in his passing I am conscious that something has gone out of my life.

My prayer is that God - will raise up others to take his place, and that

out of death there may come life to his brethren in the ministry—to

workers in the field—and indeed to all to whom he was known, and who have

valued his ministry, his example, and his influence."

"He had greatly endeared himself to many of the Keswick brethren," writes

the Rev. Evan I-I. Hopkins, of Woburn Chase, Surrey, "and was much valued

as one of the faithful champions of the Cross. There are few men in

Scotland whose loss would be more deeply felt."

"One of the most lovable and unselfish men I have ever met," writes

another English Church clergyman, "his life and character were an

inspiration."

The two appreciations that follow appeared in The Life of Faith. of

February, 1913, and are given here as linking Mr. Mackinnon with Keswick.

THE SUDDEN HOME-CALL OF A BELOVED AND FAITHFUL SERVANT OF THE MASTER.

It is difficult to understand why some men are cut down in what seems the

prime of life and in the midst of all their activities, and when some man

whom we think cannot be spared is suddenly removed to higher service, we

can only bow the head and say in awed humility, "Thy will be done." These

are the feelings which possess our minds to-day, when

we think of the sudden home-call of the Rev. Hector Mackinnon, M.A.,

minister of Shettleston Parish Church, Glasgow. A fortnight ago he

appeared well and strong. Then he caught a chill, pneumonia supervened,

and on Tuesday of last week he passed from the service of earth into the

presence of the Master, whom he loved so well and served so faithfully. To

the widow and two young boys left alone in their terrible sorrow our

hearts go out in tenderest sympathy; may the Divine comfort be their

portion, and may it be abundantly realised in their experience that God is

indeed a Friend to the widow and the fatherless.

A splendid example of the Highlander, Mr. Mackinnon was

only forty-six years of age, and to look at his tall, manly figure and

robust, vigorous frame, one could not but think that there lay before him

many years of blessed service. For he was a happy worker in the vineyard

of his Master, and loved to preach the Gospel in all its rich and glorious

fullness. He had no sympathy whatever with the modern tendency to make the

pulpit the medium through which purely social doctrines are proclaimed; it

was ever his aim and ambition to make full proof of his ministry, and to

so present the message of salvation that sinners would turn to God for

pardon and acceptance. Burning with Celtic fire, Mr. Mackinnon preached

with such eloquent earnestness that in the early days of his ministry he

became known as the" Spurgeon of the North—a title which was not

misplaced, for the power of the young Highlander was felt over a wide

area, and attracted large congregations wherever lie preached. As an

illustration of the fruits of his faithful ministry, it is told of a

Highland girl that, when asked how she became a Christian, she answered,

"Since I was a child I have been taught the Scriptures, and longed to be

the Lord's, but when I came to Campbeltown, I went to Mr. Mackinnon's

church. He made the way of salvation so plain that I accepted Christ, and

every time I heard him speak after that he brought me near to God."

Mr. Mackinnon, in addition to the heavy duties of a

wide parish and a large congregation, took a leading part in every good

work. For the past twelve years he was a regular attender at the Keswick

Convention, and, on occasion, his voice was heard from its platforms. He

loved the truths for which the movement stands, and his last contribution

to the pages of The Life of Faith, a few months ago, was in the nature of

a testimony to the value of the " Keswick message." As secretary also of

the Bridge of Allan Convention, he exercised a useful and valued ministry,

and the fact that last year's gathering of the Scottish " Keswick " was

the largest and best since its institution in 1892, was due in no small

measure to his untiring energy and consecrated tact. Mr. Mackinnon, at our

request, wrote for us an account of these meetings, remarking in the

course of his article that it was a "wonderful Convention," and that it

had accomplished a 'deep and lasting work."

And "now the labourer's task is o'er," and he stands in

the presence of the King. But the memory of his beautiful life and his

whole-hearted service will linger as a sweet and gracious influence, and

the fragrance of the memory will be an inspiration to all who knew and

loved him.

J. K. M.

Readers of The Life of Faith who were acquainted with

the Rev. Hector Mackinnon, of Glasgow, as a Convention speaker, and

through his occasional articles in our columns, will read with

astonishment and regret the announcement of his death which appears on

another page. Mr. Mackinnon was a brother greatly beloved, and in many

circles his presence will be sadly missed. Painstaking and conscientious

in all the work which he undertook, he spared no effort to give of his

best and to fulfil all his obligations. He was always ready and willing to

go the "extra mile." An experience of our own may be mentioned in this

connection. Mr. Mackinnon was a speaker at the Keswick Convention of 1911,

and going on holiday to the Western Highlands of his native land, the

proof of his address (to be revised for "Keswick Week") followed him to

his quiet retreat. Knowing the necessity of haste and the importance of

returning the proof without delay, Mr. Mackinnon at once corrected it, and

then found himself in a difficulty, for there was only one collection of

letters in the twenty-four hours, and that had already been taken. But he

was not so easily daunted. Engaging a rowing-boat, he set out for a

village five miles away, where the postal facilities were more up-to-date,

and that, too, in the teeth of a gale which eventually drove him back and

defeated his purpose. The writer will ever have happy memories of an

afternoon spent in the manse at Shettleston, and of the gracious courtesy

and love that pervaded the home-like incense from the altar of God.

A REFERENCE TO THE KESWICK CONVENTION, FROM MR.

MACKINN0N'S OWN CHURCH SUPPLEMENT.

A meeting which always affords me special pleasure is a

Christian Endeavour Rally held in the Keswick Methodist Church on the

occasion of every Convention. It was inspiring this year again to hear the

responses from district representatives according to the alphabetical

order of the names of the district from which the Endeavourers came.

Responses were given from cities and towns in England, Scotland, Ireland,

Canada, the United States, Australia, India, Germany, Norway, Sweden,

Spain. The Spanish Endeavourers gave their response in Spanish and

although few of those present fully understood what the Spaniards said,

the Holy Spirit used their response as a means of blessing to the whole

meeting. I tell you it filled one's heart to think that the Lord Jesus

Christ had disciples in so many countries, and of so many nations. He is

already seeing of the travail of His soul. I ought perhaps to mention that

the Lord's Supper was dispensed on Thursday morning of Convention week in

St. John's Parish Church, Keswick, according to the order of the Church of

England, among the officiating clergymen being Prebendary Webb-Peploe and

Rev. Evan Hopkins. I was one of some 400 ministers who partook of the

Communion, and I left that beautiful building saying within myself that

"this was none other than the house of God and the gate of heaven." If you

want your paltry denominationalism consumed, go to Keswick. You will see

there that in all the churches the Lord has His servants and followers. It

has to be confessed with regret that in some quarters there exists a

prejudice that cannot be fully accounted for, against what is called

Keswick teaching. For my part, I consider that the best way to deal with

such prejudice is to attend or persuade one to attend the Convention. I am

much mistaken if any person who ever went thither with a mind open to

conviction came away without having all prejudice removed and much

enthusiasm evoked. The fact is, Keswick teaching is scriptural to the

core, and according to the standards of all Reformed Churches, including

our own, the Scriptures are the supreme rule of faith and morals. Keswick

teaching is all in the Bible. "Holiness unto the Lord" is the keynote of

all the addresses delivered, and if this teaching be found unpalatable

and, therefore, unacceptable by many, it is, I fear, because they are

unwilling to meet God's demand upon their lives.

They simply do not want to consecrate their lives unto

the Lord. The call given at Keswick is to full personal self- surrender to

Christ Jesus and an acceptance by faith of the Holy Ghost—an experience as

possible to-day surely as it was in apostolic times. This is the message

which Christians of our age require. They have all been at Bethlehem, and

have recognised the helpless Babe as God Incarnate; they have been at

Calvary, and have seen there a Saviour dying to wash away sin's guilt. But

they have not all, I fear, visited the empty grave in Joseph's garden, and

seen the emblems of the Redeemer's victory and the proof that sin's power

has been destroyed. Oh the selfishness, the flippancy, the vanity that

mingle with modern so-called Christian service. Well did a distinguished

Highland minister of a past generation—the late Dr. Kennedy, of Dingwall---say

that an apparently active and successful church may sometimes be only the

embodiment of a great practical lie. We have scores of such churches n our

land. The true motive is not behind the service. It is performed in the

energy of the flesh, not in the power of the spirit—to gratify man, not to

glorify God. What a revolution it would cause in our church life and

activity if our members opened their hearts daily to the filling of the

Spirit ; if in all their undertakings they would wait upon the Lord, and

when He has given the lead and prescribed the method they would follow

these, come what may. We read in the Epistle to the Hebrews that all

things are to be " put in subjection under His feet," and if we are to be

His servants in anything but the name, that must be our position. Then

will He–use us to fulfil His purpose, and make the'-place of His feet

glorious. It is when we fall in utter prostration before Him, as did John

when a prisoner in the island of the JEgean Sea, that we see His right

hand extended to befriend us, and hear His words inspiring and comforting

us—" Fear not, I am the First and the Last and the Living One, I became

dead, and behold I am alive for evermore, and have the keys of hell and

death." Thus, emptied of self, freed from the bondage of self-trust, we

shall be filled with all the fullness of God. How many of those who read

these words will be led, even in the reading of them, to yield themselves

and theirs—persons, and purses, and purposes—to Him who is so worthy of

being their Lord?

In full and glad surrender

I give myself to Thee,

Thine utterly and only

And evermore to be."

H. M.

"Sit down for a little," said the Minister to us one

day after his return from Keswick, "I want to tell you this story; it is a

true story I heard it from the lips of S. D. Gordon himself. A New England

clergyman had an only son named Phil, a lad of fourteen, who was attending

school. One day the minister was surprised to receive a visit from the

boy's teacher. In the course of conversation, the teacher said, ' Is your

son well enough?'

Yes,' said the minister. ' Why do you ask?'

"Because he has not been at school to-day"' "'We

thought he was,' said the minister. Nor yesterday,' continued the teacher.

"'Oh!'

Nor the day before that.'

When the visitor had gone, the minister sat down at his

desk as usual, but he could not work. By and by he heard the garden gate

open, just at the time his son should return from school. Going to the

door, he admitted the boy himself. 'You come with me, Phil; ' and the

father and son found themselves alone together in the study.

'Were you at school to-day, Phil?' asked the father.

"The boy hung his head.

Or yesterday?

Or the day before? ' as the boy's head dropped lower.

'My boy,' said the father, and his voice was husky and

broken, 'you let us think you were.' After a few minutes' silence the

father continued, 'Now, Phil, we'll get down and pray about this.' This

was worse and worse; Phil could have borne anything else better, but

father and son got down on their knees. Phil did not know what his father

said in that prayer, but he knew he was weeping, and his own eyes were not

dry. When they rose the father said, 'Now, Phil, my boy, there is a law

which cannot be broken; all wrongdoing must be followed by suffering. You

will go up to the attic for three days and nights, just the time you

allowed your mother and me to think you were at school when you were not.'

Then Phil took his punishment like a man, and made his way to the attic,

where a little bed was made up, and his meals brought to him. In the

evening the minister and his wife were strangely silent and sad at

tea-time they could not eat anything, and afterwards the minister could

not see to read, and his wife could not see to sew. And so they sat on

until the hour for retiring, but neither wished to go to bed. Ten o'clock

came, eleven, twelve, and at one they slowly rose and went upstairs. But

it was no good; after an hour's tossing the minister said, 'Why don't you

sleep, mother?

'Oh, I'm sleeping,' said his wife, 'why don't you

sleep? ' 'I'm just going to sleep now,' said he. After another hour's

tossing, the minister said, ' Mother, I can't stand this any longer, I'm

going up to Phil!'

And to the attic he went, where in the darkness, with wide-open eyes and

tear-stained cheeks, lay his boy Phil. Now father and son had always been

friends chums—so the father got down beside his

boy, and locked in each other's arms, they passed the night, and the next

night, and the night after that. And so the father shared his son's

punishment."

Long before Mr. Mackinnon had finished this story, he had had to stop, for

both himself and his wife were crying like two children. You see, God's

love is like that. And if the Bible teaching of Keswick succeeds in

bringing men and women to a true understanding of the great Father-heart

of God, what we need is a Keswick "in every

parish. We have told Mr. S. D. Gordon's story from memory, and think that

it concludes by saying that "Phil" is now telling the story of the Cross,

with heart and tongue of fire, in the midst of heathenism.

There is included in this Memoir Mr. Mackinnon's last address at Keswick.

The Rev. F. B. Meyer spoke immediately after Mr. Mackinnon on this

occasion, and prefaced his address by saying: "I thank God for my

brother's address, and I thank God that men like him are being raised up,

that when the older of us are removed the Ark of God will still be borne

on living shoulders."

During the winter of 1909 Mr. Mackinnon was sent by the Keswick Council as

a speaker to the Convention at Clarens in Switzerland. It was an

experience which lie most thoroughly enjoyed, and we shall never cease to

be grateful that he had this welcome respite, at least, in the midst of

his strenuous work, for lie loved travel, and was keenly interested in

other countries and peoples.

Some time before this Mr. Mackinnon had been strongly

urged to become a member of the Shettleston School Board, he having served

the community in Campbeltown in the same way. We did all in our power to

prevent his undertaking more work, protesting that it was not fair to keep

piling the agony" on to one man; for he already served on innumerable

committees and societies, and was either president or secretary in a

goodly number of them. But the Minister felt he must do his duty, and all

his duty. Once in the olden days we had both been much amused by a sage

remark from the kitchen, to the effect that oalariy was a great snare! "

So it seemed indeed, for the results of the amazing popularity thrust upon

Mr. Mackinnon everywhere were more work, and still more work. He himself

was absolutely unaffected by this popularity; he never sought it, never

went out of his way to win it, and seemed indeed to think nothing of it

beyond endeavouring to justify any confidence which was placed in him.

Over and over again he showed plainly that he thought far more of the good

opinion of the little company at home than of the world outside.

No sooner had he been elected a member, and chosen

chairman of the School Board, than there seemed suddenly to come into

existence an incredible number of persons from various places, all

desirous of obtaining situations of one kind or another under the

Shettleston School Board! No one ever seemed to grudge the long tramp up

to the manse, unless indeed some one was disappointed in not finding the

Minister at home, which happened as often as not. The chairmanship of the

Board added tremendously to his already heavy correspondence, and at the

end of two years he was compelled to relinquish his duties as a member.

Immediately after his passing, a year ago, the members

of the Board met, and unanimously placed on record their " deep

appreciation of his high qualities as a chairman. Kind and courteous at

heart, he ever brought that influence to bear on the ordinary duties of

the chair; and yet, when occasion required, he proved that he could rule

with dignity and authority, if the true interests of the Board, or any of

its concerns, were at stake. He had the educational interests of the

district always before him, and was continually doing what he could to

help their prosperity. . . ."

It happened that just as the School Board Election was

proceeding, the manse was being converted into a sort of fancy fair! We

had begged the Minister to allow us to hold a Sale of Work in aid of the

Freed Slaves' Home of the Sudan United Mission, of which he was a

director.

At first he would not hear of it, because we were not

strong, and he was afraid the people would not come such a distance for a

sale. So we told him that some times when he was pleading for Foreign

Missions we could scarcely sit still in the pew, and it was hard to listen

to such preaching and do nothing. Then after a while the Minister gave in,

on condition that there would be plenty of helpers, to get whom was the

easiest thing in the world. Those willing to help were asked to volunteer,

and the result was surprising! The next thing was to ask each one to make

the undertaking a subject of prayer. Do we Scotch people not carry our

reticence in these matters a little too far? Then there was the weather!

If it rained we could not possibly expect people to come such a long way.

So we petitioned about that too. The contributions, in quantity and

quality, far exceeded our expectations, so that extra tables had to be

arranged outside. The day came, one of beautiful, unbroken sunshine, and

the people gathered in groups until there was quite a small crowd. Every

one seemed so thoroughly happy, especially the ladies who had worked very

hard, and at the end of three hours the treasurer reported having received

a sum of £36. We had thought of £20, or £25. The result of this enterprise

has been that six of the orphan freed slave children handed over to the

missionaries by the British Government have been ever since, and still

are, supported by friends in Shettleston Parish Church. How dear to the

Minister's heart was the work of trying to spread "the glorious Gospel of

the blessed God " over the whole earth ! Let us not forget.

The following summer Mr. Mackinnon took holiday duty

during the month of August at the beautiful little St. Conan's Kirk,

Lochawe, which lingers still in our memory with its quaint benediction of

peace sung at the close of each service.

"Grant us Thy peace, O God of peace and love,

Who

dwellest in the shining worlds above;

Grant us with Thee for ever to

abide,

Our shade at noon, our light at eventide,

Till that day break

when all our wanderings cease,

O God of peace and love, grant us

Thy peace, Thy peace, Thy peace."

There were frequent journeyings to and fro between

Lochawe and Shettleston, on account of School Board meetings, funerals and

marriages. We were very strongly opposed to preaching engagements during

the Minister's holiday; but it made no difference even when we went to

some little hired house of our own— he was sought for.

For a long time the Debt Extinction Scheme had been in

operation, and strenuous efforts were being made from week to week in

order to have the money paid off. The people worked hard, for they were

eager to relieve their minister of this burden, and impatient also to get

begun with a new manse. But £2,000 is a large sum of money, in addition to

the ordinary claims on a congregation, and all concerned are no doubt very

glad to forget what they passed through. The Minister did his share of the

"begging," and his friends were most kind, for in one week alone he had

subscriptions amounting to £150. At last, in 1910, with the aid of a most

welcome grant from the Baird Trust, the hail debt disappeared for ever,

and the most indifferent amongst us breathed a sigh of relief.

We now come to the story of a winter which was the

darkest but one for the manse and its occupants. One of the boys had again

been laid aside with diphtheria, and the Minister's sister had come for

medical advice about a knee which had long been the cause of grave

anxiety, while other members of the household were apparently far from

being in a state of good health. After some weeks the diphtheria patient

was set free ; but the knee remained obdurate, in spite of the very best

surgical treatment. By the end of January the pain had become so severe

that the surgeon counselled removal into town for an operation, which,

afterwards, was happily successful; and this had no sooner been

accomplished than the Minister himself was laid aside with fairly serious

illness. "You will be next," he said to us, as he lay down. He was so

patient, so anxious about his sick parishioners, and the other members of

his own household. We were just holding out, and no more, until he could

recover, after which the worst collapse of all came, and for many weeks

there was utter prostration with acute sickness, giddiness, and complete

loss of hearing. Again the Minister was the tenderest and best of all

nurses. What could be more touching than the sight of this popular

preacher struggling in a sick-room with the directions on a tin of

Benger's Food! Mastering them too, and abjectly apologising because he had

allowed the "Bishop's toe" to get in! And looking so glad and happy when

it was pronounced" just lovely!

Nothing seemed quite so bad when he was by. But we had

to submit to another removal into town. An operation, "just as serious as

any one could pass through," we were afterwards told, was performed, and

the doctors were quite hopeful that hearing would be restored. And

although they were wrong, it has yet been given to us to realise that "My

grace is sufficient for thee"; and we wait with patience in the silence,

knowing well that the next sound we hear will be the triumphant notes of

the "New Song."

It will thus be seen that this beloved minister, who

mingled daily with all classes of the community, "radiating happiness

"wherever he went; who toiled unceasingly in the dark places where "the

poor of the earth hide themselves together"; whose visits were like rays

of sunshine to the weary sufferers in city hospitals and elsewhere; who

was rejoicing and sorrowing with his people all day long; and whose pulpit

ministrations from week to week were an undiminished source of spiritual

inspiration, moral uplift and good cheer, was himself not infrequently

carrying a secret load of care. Yet we do not remember that lie ever once

used the expression "it is hard," although his deeply affectionate nature

was charged with that quick and ready sympathy for the sufferings of

others which must always mean pain to its possessor. The sight of any one

enduring physical or mental pain which he could not alleviate unmanned

him; but his habitual and unfailing eagerness to point to the bright side

of even the darkest experiences was in itself a true consolation. It was

as if he stood, a radiant figure, in the midst of us all, calling always,

"Be of good cheer, I see land!"

Having completed a course of lip-reading lessons, the

teacher in dismissing us had said very pointedly, "Now there is no excuse

for you-; I went to hear your husband preach last night, and you can

literally see the words falling from his lips! " And the first Sunday in

church afterwards we could make out very nearly the whole of the sermon;

but it is right to state that it had been read by us on the Saturday

night: throughout all the years we had enjoyed that privilege. The text on

this occasion was taken from Acts xvi. 9, And a vision appeared to Paul in

the night; there stood a man of Macedonia, and prayed him saying, Come

over into Macedonia and help us." The whole sermon was, of course, a

powerful advocacy of foreign missionary enterprise, and before closing the

preacher reminded his hearers that this was—"No self-imposed task, but a

Divine command. The Apostolic and Sub-Apostolic Church had understood and

sought to obey it. Were we entitled to stand aside and ignore it? Were we

entitled to give unto our Lord in this matter anything less than the most

we can, whether in sympathy, prayer, work, or liberality?

"Is not the fulfilment of this command essential to the

best life of the Church? Why are we not prospering better at home? One

reason is because we do not obey this injunction: ease, selfishness,

luxury, materialism and low ideals are the peril of the Church. These are

impossible only where the duty of world-wide evangelisation is recognized,

and an attempt made to perform it."

Now, our duty with regard to Foreign Missions had been

kept before us unceasingly; but there was something so arresting, so

urgent on this particular occasion, that it would have been strange indeed

if no results had followed. Gradually thereafter the change came, and just

the year before their minister was taken from them, the women of the

congregation had doubled their contributions to the cause of Missions; and

a year thereafter there was no diminution. Could there be a more fitting

memorial of such a ministry?

In 1907 Mr. Mackinnon was appointed chaplain to the

Glasgow Regiment of the Highland Light Infantry, in succession to the late

Rev. Dr. Robert Blair, of Edinburgh. Preaching before the Regiment for the

first time, in the St. Andrew's Halls, Mr. Nackinnon's opening words were

:-

I stand here as the successor of one whose memory I

fondly cherish, and by whose example I desire to walk. There was no public

duty to which the late Dr. Blair looked forward with greater interest and

eagerness than the conduct of this annual service. He had a warm

attachment for the Glasgow Highlanders, was proud of its traditions, and

rejoiced in its prosperity. I hope it is not out of place for me to say

that I highly value the honour of being appointed his successor as

chaplain of this noble Regiment, and that I shall endeavour to discharge

the duties of my office to the best of my ability, and in a manner that

will in some measure justify the confidence which through my appointment

has been reposed in me."

The Glasgow Highlanders will not soon forget his

burning words, preached from the text, " Quit you like men, be strong" (i

Cor. Xvi. 13).

Nor can we ever forget the honour the Regiment showed

him as he was borne over the "last long mile."

At a meeting of the Glasgow Highland Club, held on

February 11, 1913, the members unanimously placed on record their deep

sense of the loss which the Highland community had sustained through the

passing away of the chaplain of the regiment. In moving the resolution,

the president, Colonel W. G. Fleming, referred to " the distinction Mr.

Mackinnon gave to the proceedings on all occasions on which he was present

at the meetings as an honoured guest." Colonel Fleming also said that they

all knew what a "high type of true Highland gentleman Mr. Mackinnon

represented," and added that "when to that were united the best qualities

of a Highland minister, the result was a very perfect man indeed."

No account of Mr. Mackinnon's life-work would be

complete without mention of the deep interest he took in the children of

his flock, and in young people generally. Very soon after he came to

Shettleston he organised a "Children's Guild of Honour," which has proved

to be one of the most successful organisations in connection with the

church. "The rules of the Guild are :-

1. To speak the truth at all times.

2. To honour my

father and mother.

3. To be kind to everybody.

4. To abstain from

strong drink as a beverage.

5. To be good and do good always.

The attendance of children averaged 200 ; the meetings

are held once a week, in the evenings, when the superintendent, with his

band of bright young monitors, has always an instructive and edifying

programme in readiness for them. All these children attend church with

their parents, also the Sunday Schools, of which there are two in

connection with Shettleston Parish Church.' '—Church Supplement (1906).

Mr. Mackinnon had always "a word" for the children at the Sunday forenoon

service, with a children's hymn. At one time a series of short addresses,

prepared for the little ones, had as their subjects the animals of the

Bible, taken alphabetically—the ant, bee, coney, dove, eagle, fox,

grasshopper, horse, etc.; and at another time the precious stones of the

Bible. The older people looked forward to these sermonettes with as much

interest and pleasure as the children themselves.

We have just been reminded that the children of the

church are looking forward with great eagerness to reading the story of

their minister's life. In one way, at least, it is possible for even the

youngest to emulate his example—he was so kind. It does not appear that he

started out to do anything great, but all his life he was in earnest; he

worked hard, and kept scattering "seeds of kindness" all the time. A

picture which will be sure to interest the children is that of their

minister during the last months in the manse, sitting at his own fireside,

late at nights, busily writing, or reading, and, climbing up his arm, or

perched on his shoulder, a kitten would be frolicking. Now and again the

Minister would stop writing, look up, and smile with much amusement at the

antics of this happy little kitten, now rubbing herself against his cheek;

while Bruce lay on the rug, with averted head, and a look which plainly

meant, What right has that silly little creature to be on my master's

shoulder ! As a boy, and as a man, the Minister had always been kind to

dumb animals, and they were all devoted to him.

"He prayeth well who loveth well

Both man and bird

and beast.

He prayeth best who loveth best

All things both

great and small.

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth

all."

In still another way all the boys and girls who knew

him may imitate their minister's example—he was always willing to help,

even with work which was entirely out of his sphere. If the maids were off

duty, or on holiday, or had gone away unexpectedly, as they will

occasionally do, the Minister always came and said, "Now, what can I do to

help?" And then, in the cheeriest manner possible, he would do what he

could. We have heard a story of him, how, when he was a boy, he used to

rise very early in the morning to his studies, and would first of all

light the fire and make his mother a cup of tea. Whatever he did, he tried

to do well. It was very touching to observe how all the boys and girls

recognised him on the street, whether they belonged to his church or not.

And we know of children and young people who have gone many, many times

and laid flowers on their minister's grave ; often we have seen them

there, pathetic little bunches, quite evidently tied up by a child's hand.

And the tributes of the little ones are precious indeed.

In a very remarkable degree Mr. Mackinnon possessed

what has been called "the evangelizing tower of the hand." Widespread

testimony has been borne to his influence over men and women in the manner

of his handshaking. "He helped me a lot," said one who had never heard him

preach at all. "I used to meet him often on my way to work," said another,

"and he always stopped, shook hands, and spoke so kindly and

encouragingly; my day's work in the city seemed easier if I met him on my

way to it." He had a beautiful hand, as may be seen from the photograph

taken while he was minister of Stornoway—a reliable hand—and when men and

women were in difficulties and fighting their unseen battles, his hearty

handshake and sunny smile made them feel that things were not quite so

black as they seemed. Here at least was a man who really cared about their

welfare. A touching instance of this came to us only yesterday in a letter

from Australia, which speaks for itself

"UPPER BEACONSFIELD,

"VICTORIA, AUSTRALIA,

"January 25, 1914.

"DEAR MRS. MACKINNON,—

"I am a Shettleston man, now under the scorching suns

of the East—nearly 100 deg. to-day.

"I have just been resting in my bungalow away up here

almost on the summit of the Beaconsfield Hills, nearly 2,500 ft. above

sea-level, from which we can view the sea, and the passing steamers from

Melbourne to Sydney, Tasmania, etc.

"Yet how one's thoughts can return over the vast

stretches of water, and you, as it were, feel the touch of the hand. Yes,

I feel the touch, and the power on me, which your beloved husband gave me,

when bidding me Godspeed some eighteen months ago. You may remember me

coming to the manse. Little did I think he would so soon be taken away; so

young, so useful; but it is only a removal for higher service, God has

said.

"I have been reading the life of Henry Kirke White, and

the tribute paid to his memory comes to my mind at once, as I look at the

picture of your dear husband hanging on my wall here. When I received the

news, with his portrait in the paper, I cut it out, put it into a frame,

and wrote underneath, 'A man I knew, and loved much.'"

"Here is the tribute:-

"Such talents and such piety combined,

With such

unfeigned humility of mind,

Bespoke him fair to tread the way to fame,

And live an honour to the Christian name;

But Heaven was pleased to

stop his fleeting hour,

And blight the fragrance of the opening flower

We mourn, but not for him, removed from pain;

Our loss we trust is

his eternal gain

With him we'll strive to win the Saviour's love,

And hope to join him with the blest above."

"This is my tribute to your dear husband, and I felt, as it were, impelled

to write you.

"Yours sincerely,

"W— R—."

And away, far away, in other distant places, where the home mails are so

eagerly looked for, the young men in their offices read to one another the

newspaper accounts of his life and work; and those of them who had never

known him, never heard his name till then, spoke softly of him for days

afterwards, and said wonderingly, "What a good

man he must have been!" Who shall say his work is done? Does it not rather

seem that his best work is but beginning? Is it not enough that men and

women everywhere in speaking of him, "mingle his name with naming of the

Lord?

"Who was he, to begin with?" asked some in those far-off places. He was

only the son of a small farmer, in a lonely little wind-swept isle; but as

he stepped into his young manhood, he took Jesus Christ with him, and

never faltered or turned back from his allegiance.

"If Jesus Christ is a man—

And only a man-I

say

That of all mankind I cleave to Him,

And to Him will cleave

alway.

If Jesus Christ is a God—

And the only God—I sweat

I will follow Him through heaven and hell,

The earth, the sea, the

air."

Disappointment will doubtless be felt because this narrative includes none

of the sermons which were helpful to so many people. But by Mr.

Mackinnon's will all his sermons were to be destroyed, as having done

their work. Even had it been possible to publish them, there would still

have been disappointment—readers would have missed the inspired preacher

behind them; the glow and the fire would have been

wanting, for so often the thoughts that breathe and the words that burn

"came to him just as he stood before the people. Many have recalled the

way in which he used to walk across the chancel to the pulpit—the head and

shoulders bent forward as if weighted with his message; the footsteps

eager, almost hurried, suggesting that "the King's business requireth

haste." But he was never anything less than absolutely natural in his

conduct of the services of the sanctuary, and was singularly free from

affectation and artificiality at all times. He never went to the pulpit

unready; sermons were always patiently thought out, written and re-written

(even if it meant sitting far into the night)—so that when he came to

deliver them, he was almost independent of his manuscript. But the secret

of his power as a preacher lay, not in any studied eloquence, but in his

earnestness—his intensity—"too sore on himself," the Campbeltown people

said. It was not possible for him to be otherwise ; in his preaching he

seemed to pour out his whole soul on the people, and the after- exhaustion

was sometimes very great. He was gifted with a strange power in the

pulpit; he could subdue, soften, shrivel, melt and move to tears those of

us who listened to him. May we not think that this intensity, this

soul-yearning over the people, was specially given him because in the

foreknowledge of God the time allotted to him for the doing of his work

was to be short? He read and studied incessantly, and dispensed to his

people a mental wealth fed with the Bible and the best literature of the

day. Many of his hearers have testified to the help they received even

from the quotations which he sometimes introduced into his sermons. It is

by request that a few of these are given here; "he had a way of saying

things which made them keep ringing in your ears all the week," said one,"

and it is hard when you can't remember it all."

An Easter sermon some time ago concluded with the

verses:

"I say to all men far and near

That He is risen

again,

That He is with us now and here,

And ever shall remain.

"And what I say, let each this morn

Go tell it to

his friend,

That soon in every place shall dawn

His Kingdom without

end.

The fears of death and of the grave

Are 'whelmed

beneath the sea,

And every heart now light and brave

May face the

things to be.

He lives, His presence bath not ceased,

Though

foes and fears be rife

And thus we hail in Easter's feast

A world

renewed to life."

One of his brother-ministers says that "in the

inflections of his voice there was that touch of Celtic plaintiveness

which gives the Highlander such a command over his fellow-men." Who did

not feel this in his rendering of Whittier's beautiful lines?

I know not what the future hath

Of marvel or

surprise,

Assured alone that life and death

His mercy underlies.

And if my heart and flesh are weak

To bear an

untried pain,

The bruised reed lie will not break,

But strengthen

and sustain.

* * *

And so beside the Silent Sea

I wait the muffled oar;

No harm from

Him can come to me

On ocean or on shore.

I know not where His islands lift

Their fronded palms in air;

I

only know I cannot drift

Beyond His love and care."

Or again

"Our Friend, our Brother, and our Lord,

What

may Thy service be?-

Nor name, nor form, nor ritual word,

But

simply following Thee.

"We bring no ghastly holocaust,

We pile no graven stone;

He serves

Thee best who loveth most

His brothers and Thy own.

"In vain shall waves of incense drift

The

vaulted nave around;

In vain the minster turret lift

Its brazen

weights of sound.

"The heart must ring Thy Christmas bells,

Thy

inward altars raise;

Its faith and hope Thy canticles,

And its

obedience praise."

In a sermon, the texts of which were—"The love of God, which is in Christ

Jesus our Lord" (Rom. viii. 39) and "We are more than conquerors through

Him that loved us" (v. 37), the love of God in Christ Jesus, and the sense

of victory which this brings, were set forth with great power and beauty

in the simplest possible language. "I like that word more than

conquerors," said the preacher, "it is oftener on my lips in preaching

than any other scripture expression. When shall we understand that the

conflicts of life evoke the latent faculties of the

soul, and bring out its strength and beauty, and fit it for flights and

felicities far beyond our most ardent dreams? O beloved, whose feet have

still to tread the fiery embers, be not discouraged, do not lose hope, let

the words of our text uplift you now."

This hath He done, and shall we not adore Him?

This

shall He do, and can we still despair?

Come, let us quickly fling

ourselves before Him,

Cast at His feet the burthen of our care,

"Flash from our eyes the glow of our thanksgiving,

Glad and regretful, confident and calm,

Then thro' all life and what is

after living

Thrill to the tireless music of a psalm.

"Yea, thro' life, death, thro' sorrow and thro'

sinning,

He shall suffice me, for He hath sufficed;

Christ is the

end, for Christ was the beginning;

Christ the beginning, for the end is

Christ."

F. W. H. Myers.

"Come unto Me, all ye that labour, and are heavy-

laden, and I will give you rest," closed with the words of a hymn, which,

however, requires the music to bring out its full power:-

"My Saviour, Thou hast promised rest,

Oh give it

then to me,

The rest of ceasing from myself

To find my all in Thee.

"O Lord, I seek a holy rest,

A victory over sin,

I seek that Thou alone should'st reign

O'er all without, within.

"In Thy strong hand I lay me down,

So shall the

work be done,

For who can work so wondrously

As the Almighty One?

"Work on then, Lord, till on my soul

Eternal light shall break,

And

in Thy likeness perfected

I 'satisfied' shall wake."

"In all their affliction He was afflicted"-"Does

God care?"-

"Think not thou canst sigh a sigh,

And thy Maker is not by;

Think

not thou canst weep a tear,

And thy Maker is not near.

Oh, He gives

to us His joy,

That our grief He may destroy;

Till our grief is fled

and gone

He do/h sit by its and moan."

William Blake.

To some of us this last line has been rendered luminous.

"I girded thee, though thou hast not known Me" (Is. xlv. 5), was a

beseeching of young men and women especially not to leave God out of

account in their lives.

"Children of yesterday,

Heirs of to-morrow,

What are you weaving—

Labour or sorrow?

Look to your looms again,

Faster and faster

Fly the great shuttles

Prepared by the Master;

Life's in the loom,

Room for it—room."

"Children of yesterday,

Heirs of to-morrow,

Lighten the labour

And sweeten the sorrow.

Now—while the shuttles fly

Faster and

faster,

Up and be at it—

At work with the Master.

He stands at

your loom,

Room for Him—room.

Children of yesterday,

Heirs of to-morrow,

Look at your fabric

Of labour and sorrow,

Seamy and dark

With despair and disaster,

Turn it—and lo,

The design of the Master

The Lord's at the loom,

Room for Him—room."

How clear was his teaching as to Conversion—he had passed through it

himself, he told his people once. It was not new light—he had known the

Gospel from childhood; what happened was "the creation of a new personal

relation to God, a great reconciliation with God, a birth into sonship, a

permanent change at the centre of his spiritual being, which had been the

dominant element of his consciousness ever since.

"'I have no other argument,

I want no other

plea;

Jesus died for all mankind,

And Jesus died for me.'"

It was to be expected that personal holiness

would be the one thing longed for in such a life.

"Search me, O God ! my

actions try,

And let my life appear

As seen by Thine

all-searching eye—

To mine my ways make clear."

If we offer this prayer sincerely, we shall get answers that will startle

us," he told his hearers. But there would be "no victory without

conflict."

"Then welcome each rebuff

That turns earth's smoothness rough,

Each

sting that bids nor sit, nor stand, but go

Be our joys three parts

pain,

Strive, and hold cheap the strain

Learn, nor account the pang;

dare, never grudge the throe."

But the most insistent note in Mr. Mackinnon's preaching, and one which

seemed to ring out more and more clearly in all the Shettleston sermons,

was the sure hope of immortality through our risen, glorified Redeemer.

Only one who believed with his whole heart and soul, as he did, that Jesus

Christ rose from the dead, that He is alive for evermore, and that

therefore He has "abolished death, and brought life and immortality to

light through the Gospel," could have become the means of suffusing into

countless other lives the unspeakable joy of the same glad hope. "Because

Jesus Christ has revealed immortality and exemplified it," he cried, " I

am absolutely certain that I cannot die. We have an instinct of

immortality, and although it is not a mathematical certainty, like death,

yet instinct is reliable within certain limits. But we have more than an

instinct—we have Christ's empty grave! No fact of history is better

attested than this, which is 'the cardinal point of our Christianity,'

and—

'I intend to get to God;

It is to God I speed so fast;

And on God's

breast, my own abode,

Those shores of dazzling glory past,

I'll

lay my spirit down at last.'

Often, too, he would speak to his people of the

revelations of Science and Philosophy, the mysteries of Astronomy and the

fancies of Astrology, but only to show further how all things are "working

together for good" to those who love God. But "read your Bible, read your

Bible," he would say—"a Bible laid open, millions of surprises " (George

Herbert).

The writer can never forget the light which shone in his face when, some

years ago, he quoted to her for the first time-

The face of Death is towards the Sun of Life,

His shadow darkens

Earth; his truer name

Is 'Onward'; no discordance in the roll

And

march of that Eternal Harmony,

Whereto the worlds beat time, tho'

faintly heard

Until the great Hereafter."

Tennyson.

Nor again, when both had been reading a book by

a friend on " Christian Theism," and we asked if he had seen the following

note which occurs in it :-

It is hoped that it is not out of place to state here that, shortly after

the MS. of this book 1 had been sent to the publishers, the writer had the

misfortune to lose a devoted wife. She was deeply interested in this

subject, and before she passed away the writer promised to cherish her

spiritual presence, and asked her (if it was right and not hurtful) to try

and manifest her presence to him. He feels bound to say he believes she

has done so."

"Yes," was all the Minister said, but his face was shining.

To the above testimony we can now, humbly and reverently, add our own,

expressed in the following lines :-

Oh, could I tell, ye surely would believe it

Oh, could I only say what

I have seen!

How should I tell, or how can ye receive it,

How, till

He bringeth you where I have been?

Mr. Mackinnon was unconscious of the way in which his own faith and

example were making other men and women strong. "He helped me in my

spiritual life more than any other man I know," said one; "all I am I owe

to his preaching and example," wrote a bright, earnest young Christian.

And it was good to be told how much he had been to many of his brother

ministers.

"I loved him, for he was one of the most lovable

of men," wrote an Edinburgh minister. "Just a few weeks ago I had a long

chat with him, and after we had parted, I said to another friend, 'There

is one man in the world whom I love and reverence—Mr. Mackinnon, of

Shettleston.' His faith quickened mine, and his beautiful character

inspired me. In my memory I hold him, and I thank God for what he was to

me. It will comfort you to know that he helped me in my Christian life. .

."

He was not "goody-goody." No one could have mourned over personal faults

more than he did; he could be made angry, very angry; some of us in

Shettleston Church can remember having seen him more than once as one of

"God's angry men ""from his right hand went a fiery law for them— yea, he

loved the people;" but he simply could not keep his anger for five

minutes. Never once in his own home was he known to speak a hasty word

with-c out immediately afterwards saying he was sorry and showing that he

was so. What attracted and won the admiration of all who knew him was a

moral robustness, a magnanimity of soul, a sort of sanctified naturalness

in all he said and did. He was what God wanted him to be, a true man. Like

every other faithful minister, he had his times of stress and strain, but

in that great, generous heart there were no unloving thoughts of any one.

The last two years-1911---1912—were those during which the strenuousness

of Mr. Mackinnon's life had begun to tell. In 1911 he suffered much from

nasal catarrh, which threatened to become, and ultimately did become,

chronic. Every known remedy was tried, and many doctors consulted. Much

was said and written after his passing which was calculated to have given

the impression that Mr. Mackinnon did not take care of

himself, that he deliberately overworked. It is enough to say here that

all such impressions are utterly and entirely wrong. Mr. Mackinnon took

every care to keep himself in good health recognizing that it was his duty

to do so. Very pathetic were the patience and perseverance with which for

two years he tried to rid himself of the malady which must have undermined

his constitution. That he was overworked, sadly so, is only too true. But