|

Dr. Carlyle (born January 26, 1722, died August

25,1805) is memorable as a member—though an inactive one—of the

brilliant fraternity of literary men who attracted attention in Scotland

during the latter half of the eighteenth century. His father was the

minister of Prestonpans. He received his education at the Universities

of Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Leyden. While he attended these schools of

learning, his elegant and manly accomplishments gained him admission

into the most polished circles, at the same time that the superiority of

his understanding, and the refinement of his taste, introduced him to

the particular notice of men of science and literature. At the breaking

out of the insurrection of 1745, being only twenty-three years of age,

he thought proper to enrol himself in a body of volunteers, which was

raised at Edinburgh to defend the city. This corps was dissolved on the

approach of the Highland army, when he retired to his father's house at

Prestonpans, where the tide of war soon followed him. Sir John Cope

having pitched his camp in the immediate neighbourhood of Prestonpans,

the Highlanders attacked him early on the morning of the 21st of

September, and soon gained a decisive victory; Carlyle was awoke by an

account that the armies were engaged, when, in order to have a view of

the action, he hurried to the top of the village steeple, where he

arrived only in time to see the regular soldiers flying in all

directions to escape the broadswords of the Highlanders.

Having gone through the usual exercises prescribed

by the Church of Scotland, he was presented, in 1748, to the living of

Inveresk, near Edinburgh. In this situation he remained for the long

period of fifty-seven years. His talents as a preacher were of the

highest order, and contributed much to introduce into the Scottish

pulpit an elegance of manner and delicacy of taste, to which this part

of the United Kin°--dom had been formerly a stranger, but of which it

has since afforded some brilliant examples. In the General Assembly of

the Church of Scotland, Dr. Carlyle acted on the moderate side, and,

next to Dr. Kobertson, was one of the most instrumental members of that

party in reducing the government of the Church to the tranquillity which

it experienced almost down to our own time. It was owing chiefly to his

active exertions that the clergy of the Church of Scotland, in

consideration of their moderate incomes, and of their living in official

houses, were exempted from the severe pressure of the house and window

tax. With this object in view he spent some time in London, and was

introduced at Court, where the elegance of his manners, and the dignity

of his appearance, are said to have excited both surprise and

admiration. He succeeded in his efforts, though no clause to that

purpose was introduced into any Act of Parliament. The ministers were

charged annually with the duty, but the collectors received private

instructions that no steps should be taken to enforce payment.

Public spirit was a conspicuous part of the

character of the Doctor. The love of his country seemed to be the most

active principle of his heart, and the direction in which it was guided

at a period which seriously menaced the good order of society, was

productive of incalculable benefit among those over whom his influence

extended. He was so fortunate in his early days as to form an

acquaintance with all those celebrated men whose names have added

splendour to the literary history of the eighteenth century. Smollett,

in his "Expedition of Humphry Clinker," a work in which fact and fiction

are curiously blended, mentioned that he owed to Dr. Carlyle his

introduction to the literary circles of Edinburgh. After mentioning a

list of celebrated names, he adds—"These acquaintances I owe to the

friendship of Dr. Carlyle, who wants nothing but inclination to figure

with the rest upon paper."

Dr. Carlyle was a particular friend of Mr. Home,

the author of Douglas, and that tragedy, if we are not misinformed, was,

previous to its being represented, submitted to his revision. It is even

stated, although there appears no evidence of the truth of the

assertion, that Dr. Carlyle, at a private rehearsal in Mrs. Ward's

lodgings in the Canongate, acted the part of Old Norval, Dr. Eobertson

performing Lord Randolph—David Hume, Glenalvon, and Dr. Blair!! Anna—

Lady Randolph being enacted by the author. He exerted, as may be

supposed, his utmost efforts to oppose that violent opposition which was

raised against Mr. Home by the puritanical spirit, which, though by that

time somewhat mitigated, was still far from being extinguished in this

country; and successfully withstood a prosecution before the Church

courts for attending the performance of the tragedy of Douglas.

Dr. Carlyle rendered an essential service to

literature, in the recovery of Collins' long lost "Ode on the

Superstitious of the Highlands." The author, on his death-bed, had

mentioned it to Dr. Johnson as the best of his poems, but it was not in

his possession, and no search had been able to discover a copy. At'last,

Dr. Carlyle found it accidentally among his papers, and presented it to

the Eoyal Society of Edinburgh, in the first volume of whose

Transactions it was published ; and by the public in general, as well as

by the author himself, it has always been numbered among the finest

productions of the poet.

It is much to be regretted that Dr. Carlyle favoured the world with so

little from his own pen, having published scarcely anything except the

Report of the Parish of Inveresk, in Sir John Sinclair's Statistical

Account, and some detached pamphlets and sermons. To his pen has been

justly attributed "An Ironical Argument, to prove that the tragedy of

Douglas ought to be publicly burnt by the hands of the

hangman."—Edinburgh, 1757, 8vo, pp. 24. It is understood that Dr.

Carlyle left behind him, in manuscript, a very curious Memoir of his

time, which, though long delayed, we have now reason to believe will

soon in part be given to the world.

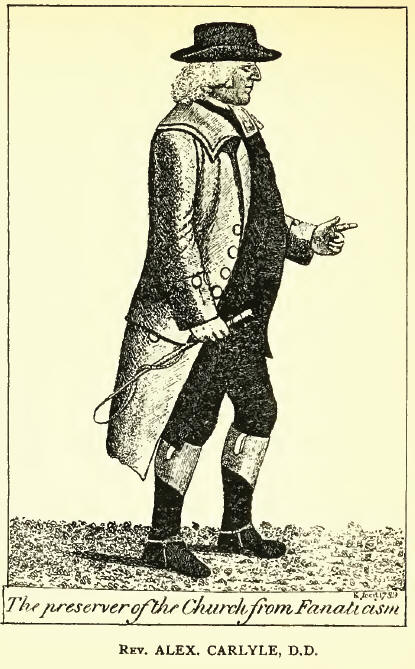

With the following description of the personal

appearance of Dr. Carlyle, when advanced in years, the proprietor of

this work has been favoured by a gentleman to whom the literature of his

country owes much:

"He was

very tall, and held his head erect like a military man— his face had

been very handsome—long venerable gray hair—he was an old man when I met

him on a morning visit at the Duke of Buccleuch's at Dalkeith." |