|

DUNCAN'S study of Culpepper

introduced him not only to the plants that had medicinal virtues, but to the

stars that "governed" them or had "dominion" over them, according to the

astrology of the author and the time. In order to gather the cinquefoil.

when Jupiter is "angular and strong," it is necessary for the gatherer to

know not only Jupiter, and his position in the sky, but those relations to

the other planets and constellations that constitute his angularity and

strength; if loosestrife is "an herb of the Moon and under the sign Cancer,"

and if rue is "an herb of the Sun and under Leo," to do the plants justice,

you must not only know the Sun and the Moon, which, as the facetious

astrologer says, "every boy that plays with a pop-gun will not mistake," but

you must know both the Lion and the Crab, especially if either of the former

is in "the house" of the latter. And this knowledge is all the more

necessary to a true Culpepperian physician, for doth not the mild and

learned Culpepper asseverate—"I would willingly teach astrologers to be

physicians, for they are most fitting for the calling; if you will not

believe me, ask Dr. Hippocrates and Dr. Galen, a couple of gentlemen that

our College of Physicians keep to vapour with, not to follow"? Still true of

many other things than physic, most redoubtable Culpepper! It was

impossible, therefore, for any one, much less an earnest disciple like John,

not to look into the stars. This he did with ardour, first, it may be, for

the sake of the "government" of the herbs he gathered, but by-and-by for

their own sakes, and for higher practical ends. Whether he became an

astrologer or not, John became an enthusiastic astronomer.

He obtained text-books on

Astronomy at an early date, such as "Astronomical and Geographical Lessons,"

by James Levett, published in 1814, and the "Catechism of Astronomy," and he

studied charts of the heavens. By-and-by he grew so familiar with them that

he could with ease distinguish and name them singly and in their

constellations, and point them out to those friends who would listen to such

heavenly lore. So eager did he become in his studies that, on clear frosty

nights, he was seen setting off for the tops of bare hills commanding an

uninterrupted view of the skies, and he did not return to his cold couch

till long after midnight—a foolish and thankless proceeding, in the eyes of

his wiser and more comfortable neighbours; so that he began to be thought

"no very wise."

When staying at various

places, John used to set up dials on dikes beside the house she lived in, to

guide him in his observations. He would be busy at these things in the dead

silence and the dark, when, all at once, down went the dial at the far end

of the dike, followed by the crackle of bursting laughter, and the

hurry-scurry of running feet, the meaning of which John knew too well. It

was some of the mischief-loving sparks of the neighbourhood, who were thus

making fun of the curious weaver's crazy pursuits - "moon-struck madness,"

in their eyes. And such annoyances were frequent and trying enough. Hence he

was obliged to seek seclusion at a distance, whither their fears of the dark

and its denizens effectually prevented their following him, or at an hour

when even the restless spirit of fun was conquered by the more potent god of

sleep.

While he stayed at Milldourie,

close by Paradise, he had very good sites for stellar observation, on the

hills around that beautiful hollow, where the clearness of the sky in a

frosty night would be intensified by the dark foliage of the trees. For

wider outlook, the hilltop near Corilabb, eight hundred feet above Paradise,

where he lived for year, was free of trees, and he was often found there

when most were beneath the cosy blankets; while just above this, Cairn

William, double the height, without a tree for more than two hundred feet

from its summit, was a splendid point of vantage, commanding an

uninterrupted view of the whole heavens above, and a wonderfully impressive

prospect of the darkened world below, with Benachie in front and the deep

Don between.

It was most certainly no

wonder that, in those days, when science was quite unheard of amongst the

common people, a man who pursued such unearthly gazing at these uncanny

hours should be thought to be more than queer, and to be decidedly affected

by the moon to which he paid such absurd devotion. Hunting for weeds was

sufficient to rouse suspicion, but this glowering nightly at the stars more

than completed the proof. The man was "mad" or "wud —or "next door to it."

Akin to his astronomical

pursuits, was the then common study of Dialling. When clocks and watches

were comparatively scarce, the making of dials was, of course, an art of

great practical value, and was much followed, up to fifty years ago. Their

theory and practice were often taught in schools, and a knowledge of the

subject was frequently a requirement of teachers, some of whom were

practical masters of the art, and have left, in various parts of the

country, very creditable specimens of their skill in this department of

practical astronomy. [The elaborate dial in the churchyard of Currie, near

Edinburgh, made by the late parish teacher, Mr. Palmer, is a noteworthy

example.] It will be remembered by those who have read the life of that

remarkable genius, James Ferguson, the Banffshire stargazer, as, told by

himself and Dr. Henderson in a book of intense interest and fullest

information, ["Life of James Ferguson, F.R.S., in a brief autobiographical

account, and further extended memoir by E. Henderson, LL.D." (Fullarton and

Co., 1867.)] that dialling was one of the early subjects to which that young

stargazer directed attention guided by "God Almighty's scholar," as his

disciple calls him, Alexander Cantley, mathematician, astronomer and

diallist.

John Duncan also became a

theoretical and practical diallist, making dials for himself and his

friends, and specimens of his handiwork still exist in and round the Vale of

Alford. Among his papers, there remain several very creditable drawings of

different kinds of dials, upright and horizontal. Some of his correspondents

also worked at the same art, and sent him sketches of dials they had seen or

planned, with elaborate details of the form and height of the stile, the

elevation of the plate, the length of the hour line, and the divisions of

the hour circle. In 1830, he also made a drawing of a large geographical

clock and dial, while staying at Longfolds.

John once possessed a watch,

bought as soon after he had completed his apprenticeship as he gained

sufficient funds, proud like all young men to possess this evidence of money

and manhood; but this his after needs, about the time he left Aberdeen,

obliged him to part with to a fellow-workman, and he never had another

wheeled chronometer of any kind. His astronomical knowledge, however, was an

adequate practical substitute. Throughout his life, he could tell the hour

with remarkable accuracy, by observing the height of the sun when in the

open air, and by the direction and length of the shadows when his beams

streamed across his loom. At night, the position of the stars was sufficient

to show the time ; and his accomplishments in this way, especially in the

dark, created profound astonishment amongst his ignorant neighbours, who

thought this another of his ways that were "no very canny."

But his desire of accuracy in

all things, including hours, which his study of astronomy had increased,

rendered him dissatisfied with this more or less indefinite mode of

measuring time ; and he made a pocket sun-dial as a substitute for watch or

clock, which he carried about with him for years, and which still remains as

a proof of his executive power and the practical direction all studies took

in his hands. It consists of a card about five inches long and three and a

half broad, nailed to a piece of thin wood of the same size, with certain

lines and figures drawn upon it and a pendent green, twisted cord, half as

long again as the card, bearing a small blue glass bead, but now without the

light plummet that once hung at its extremity. This was John Duncan's pocket

sun-watch.

Such instruments have from

time to time been advertised, and one called "the American timepiece," was

shown by Mr. John Taylor when he read an account of Duncan, before the

Aberdeen Natural History Society, in July, 1881, and exhibited John's

herbarium and pocket dial. This American instrument, advertised for one

shilling as a wonderful discovery in 1867, was found to be almost identical

with John's! It indicated the time correctly, Mr. Taylor found, to within

half an hour, while John's did so to within a few minutes, that forenoon,

the 15th of July. John's dial shows abundant evidence of careful but

constant use, being protected by a long roll of thick brown paper fastened

to it at one end, and wrapped round it twice, in the manner of a

pocket-book. The whole is of the homeliest construction, and is all the more

interesting as being entirely the handiwork of the old astronomer. This

instrument John called by its old Greek name of horologe, the hour-teller,

or, as he transformed it, his "horledge;" and as such it was known amongst

his acquaintances, who had a humorous pleasure in using the quaint word.

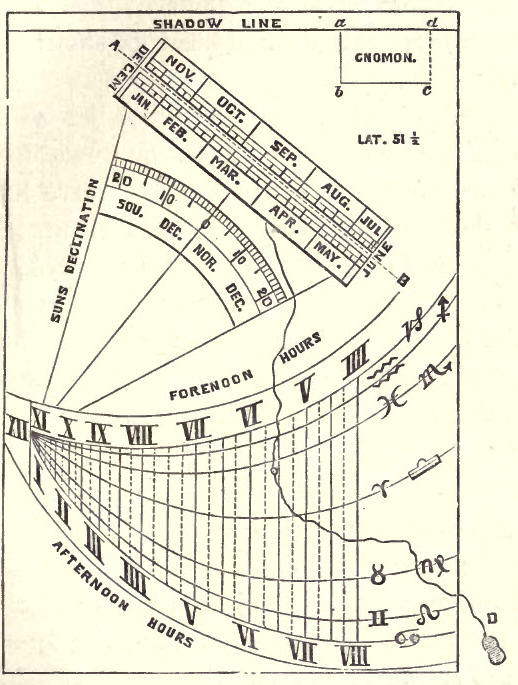

After considerable search, I

have fortunately discovered what is no doubt the original of John's

sun-watch and all subsequent forms of the same style of instrument—in a

portable dial invented by the super-ingenious Ferguson, the astronomer, and

published by him in 1759. [See "Memoir of Ferguson," p. 244, already

mentioned.] Ferguson's dial is here reproduced to show the nature of the

sun-clock thus used by our weaver. It was warranted, when rectified, to show

the hour of the day, the time of the sun's rising and setting, the sun's

declination and the days on which the sun enters the signs of the Zodiac.

Ferguson thus describes it :—

"The lines a d, a b, and b c

of the gnomon, or stile, must be cut quite through the card ; and as the end

a b of the gnomon is raised occasionally above the plane of the dial, it

turns upon the uncut line c d as on a hinge. The line dotted A B, must be

slit quite through the card, and the thread must be put through the slit to

keep it from being easily drawn out."

In Duncan's dial, the slit

was also cut through the wooden board on which the card was fastened, and

the cord inserted was fastened to a white mother-of-pearl button at the

under side which moved along the slit as required.

"On the other end of this

thread is a small plummet, and on the middle of it a small bead for showing

the hour of the day.

"To rectify the dial.—Set the

cross line on the slider to the day of the month, and stretch the thread

from thence over the angular point XII, where the curve lines meet; then

shift the bead on the thread to that point.

"To find the hour of the day

when the sun shines.— Raise the gnomon, and hold the edge of the dial next

the gnomon toward the sun, so as the upper edge of the shadow may just cover

the shadow line; and the bead then playing freely on the face of the dial

(by the weight of the plummet) will show the time of the day among the hour

lines, as it is before or after noon.

"To find the time of

sun-rising and sun-setting.—Move the thread among the hour lines, till it

either covers some one of them, or lies parallel betwixt any two ; and then

it will cut the time of sun-rising among the forenoon hour lines, and of

sun-setting among the afternoon hour lines, for the day of the year

indicated by the cross line on the slider."

Ferguson's dial also showed

the sun's declination, but Duncan had not copied that part on his drawing,

as not being of practical value for his purpose. It answered only for places

in the latitude of London, and required to be rectified for other latitudes,

which Duncan did for Aberdeen. This dial he used during the greater part of

his life, and he was often asked to consult it by his friends and others, to

their great surprise and amusement.

John took notes of various

astronomical phenomena; for instance, recording that "on the 12th of April,

1842, there was a ring about the sun from two o'clock to four o'clock," and

giving a drawing of it.

He also made a special study

of calendars, and, as already told, bought an almanack every year, which he

carefully preserved to the last. Numerous memoranda exist made by him

regarding eclipses and other celestial phenomena that were to happen during

the year, evidently transcribed, to be placed on his loom, according to his

custom, in order to be glanced at while engaged in weaving, and to guide his

nightly observations.

The related science of

Meteorology, then in its infancy, also drew his attention throughout life,

and he showed considerable skill in interpreting weather signs, the

theoretical causes of which he investigated. These his frequent wanderings

sub Jove gave him ample opportunities of observing. He possessed a

thermometer and other meteorological gauges.

From the nature of the case,

John's astronomical studies attracted more popular notice amongst his

unlearned contemporaries than even his .herb-doctoring, during his

pre-botanical days; and it would have been strange had he escaped some

relative nickname. This he did not do. For many years before he became

generally known as the botanist of the latter half of his life, he was

notorious as an Astronomer, and was in various parts spoken of as "the

star-gazer." In some places, he was called "Johnnie Moon," or as the

Aberdeen tongue expresses Luna's name, "Johnnie Meen," a form as near to the

original Anglo-Saxon mona, and the Gothic mena, as our modern English one,

which we have no more reason to plume ourselves upon than the Aberdonians on

theirs.

Another early cognomen that

our harmless astronomer received, was the strange one of "the Nogman," by

which he was generally known in several districts, but which none of his

nicknamers could explain. The explanation, however, is not far to seek.

Another name for the stile, index, or pin of a sun-dial that throws the

shadow is, as we have seen, the Greek word gnomon, whence the art of

dialling was called gnomonics. This odd-looking word, John, with his home

education, faithfully pronounced every letter of, and inverting, from his

short sight, the first two letters, called it "nogmon." As he talked a great

deal about it in connection with his dials, the queer-sounding word was

eagerly caught up by the bumpkins, and speedily transferred to the man

himself, under the idea that it was a personal designation, denoting a kind

of man, a "nogman."

It was more truly descriptive

than they knew, for the Greek word

, or gnomon, means

one that knows, a knowing man, which John surely was. It is not a little

curious that this quiet wanderer on the earth's surface should have received

a name almost identical with that of the Rosicrucian guardians of hidden

treasure, the Gnomes who dwelt in the earth's centre. But John "the nogman"

was a true gnome in more than in oddness of aspect; for he was a guardian of

real gold, "the hidden treasures of wisdom and knowledge." , or gnomon, means

one that knows, a knowing man, which John surely was. It is not a little

curious that this quiet wanderer on the earth's surface should have received

a name almost identical with that of the Rosicrucian guardians of hidden

treasure, the Gnomes who dwelt in the earth's centre. But John "the nogman"

was a true gnome in more than in oddness of aspect; for he was a guardian of

real gold, "the hidden treasures of wisdom and knowledge." |