|

It was at this juncture that Donald Smith came to

the rescue. He had surveyed the situation from afar. Two thousand miles

away, in Montreal, he pondered the matter—perceived the danger— realized

the weakness of Macdougall's policy and discovered a remedy. The man for

the occasion must be one who understood both sides, could deal with both,

had the confidence of both and could be on the spot in person to promote a

settlement. And it was in no spirit of self-esteem that he recognized in

himself the man for the post. lie believed in himself. He believed that he

could pacify and control the turbulent spirits, and, with no desire to

exalt himself, he offered his services to the Government. He announced his

intention to go to Red River to pour oil on the troubled waters of

political life.

What a change in his fortunes! He had spent thirty

years in obscurity, living a rough and toilsome life, the companion of

rough men, trading with Indians and Esquimaux, enduring physical hardships

and exposed to many a hazard. His existence, so far as society was

concerned and the conduct of affairs, was of the narrowest and most

confined. Then suddenly he found himself in the stir and strain of public

matters of the highest importance, the confidant of great statesmen and

entrusted with a commission of the most delicate character. It was a

tribute to the value of his experience, and to the wise use he had made of

those years of discipline that, when the occasion came, he was ready to

meet it. It is interesting to wonder what might have happened had he

failed in the duty that was laid upon him. The whole future of the

North-West and, indeed, of the young Dominion, was involved in the issue

of his mission.

In order that he might be in a better position to

negotiate, the authorities at Ottawa decided that he should go, not simply

as an official of the Hudson Bay Company, but as "Commissioner" from the

Dominion Government. To this end he received a letter from the Secretary

of State, appointing him Special 'Commissioner, "to inquire into and

report upon the causes, nature and extent of the obstruction offered at

the Red River, etc., etc.," and also to consider and report on the most

advisable mode of dealing with the Indian tribes in the North-Western

Territories.

He started on his mission without delay, lie left

Ottawa on the 13th of December, and travelling by rail, stage coach and

sleigh, reached Pembina, on the American border, about midnight Christmas

Eve. He had taken eleven days to make a journey now accomplished in one

day and a half.

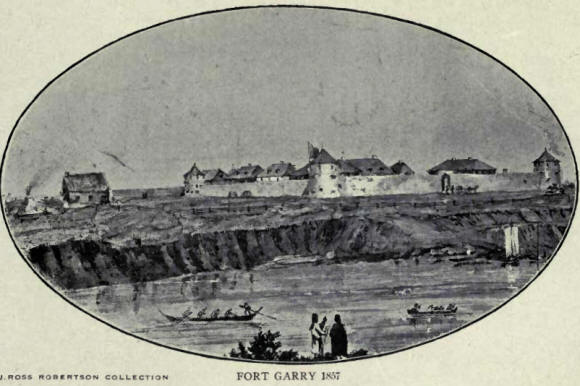

On the 27th of December he reached Fort Garry. There

he met for the first time the so-called President, Louis Rid, who was the

head and front of the rebellion, and whose reckless ambition came near to

producing civil war. As he refused "to take an oath not to leave the fort

that night, nor to upset the Government," Mr. Smith was kept a prisoner

for nearly two months, though he was allowed considerable liberty. These

two months represent a most critical period in the history of Canada. It

was a trial of strength between the Canadian Commissioner and the

half-breed rebel, with the advantage at the start on the side of the

latter. There is no doubt that Riel was afraid of his antagonist, lie was

a man of different calibre from those with whom he had had to deal, a man

not easily frightened, of a powerful personal presence and also the

official representative of the Dominion and Imperial Governments. After

many discussions, he agreed to hold a meeting at which Mr. Smith could set

forth the object of his mission and explain the intentions of the

Government. This meeting was held on January 19th, 1870. It was a

memorable gathering. A thousand people attended, and as there was no hail

large enough to hold them, they met in the open air with the thermometer

20 below zero.

As a result of this meeting, forty representatives

were afterwards elected to consider the message of Mr. Smith. Considered

in the light of the subsequent history of the Canadian North-West, it is

doubtful if a more important meeting was ever held. Affairs were critical.

Riel and his friends were in possession and were loath to give up their

position and were ready to oppose every proposal and raise every

objection. Mr. Smith made a speech which was full of the wise and

conciliatory spirit, he asserted that he was there in the interests of

Canada, but only so far as they were in accordance with the interests of

that country. He declared that so far as his connection with the Hudson

Bay Company was concerned, he was ready at the moment to give up his

position. lie expressed the hope that his efforts might contribute to

bring about peaceably, union and entire accord among all classes of people

of the country.

He then read a letter which had been written him by the Governor-General

of Canada, the Hon. John Young. In that letter he was authorized to assure

the people "that the imperial Government had no intention of acting

otherwise, or permitting others to act otherwise, than in perfect good

faith 'towards the inhabitants of the Red River district of the

North-West." He was to assure them that the different religious

persuasions would be respected; titles of property would be carefully

guarded; existing franchises should be continued and that "right shall be

done in all cases."

But the greatest impression was produced when he, in spite of the efforts

of Riel to prevent it, read a communication direct from the Queen herself.

There is a touch of romance in the scene— a letter from the greatest

Sovereign of the age being read to a motley crowd of her subjects on that

far-away prairie in the depth of winter. When the reading of this letter

was finished, the assembly showed their appreciation by cheer after cheer.

It is worth while to give the communication in full.

"The Queen has heard with surprise and regret that certain misguided

persons have banded together to oppose by force the entry of the future

Lieutenant-Governor into our territory in Red River. Her Majesty does not

mistrust the loyalty of persons in that settlement, and can only ascribe

to misunderstanding or misrepresentation their opposition to a change

planned for their advantage. She relies on your Government to use every

effort to explain whatever misunderstandings have arisen—to ascertain

their wants and conciliate the good will of the people of the Red River

settlement. But in the meantime, she authorizes you to signify to them the

sorrow and displeasure with which she views the unreasonable and lawless

proceedings that have taken place; and her expectation that if any parties

have desires to express, or complaints to make, respecting their

conditions and prospects, they will address themselves to the

Governor-General of Canada. The Queen expects from her representative

that, as he will he always ready to receive well founded grievances, so

will he exercise the power and authority she entrusted to him in the

support of order and the suppression of unlawful disturbances."

A "Bill of Rights" was adopted and it was decided to send delegates to

Ottawa to confer with the Dominion Government. Meanwhile a Provisional

Government was formed, of which Riel became President, and O'Donoghue, a

Fenian priest, the Secretary of the Treasury. The next few weeks were

marked by stormy episodes. Six hundred men marched on Fort Garry to secure

the release of the prisoners confined there. On the approach of this

force, Riel set the prisoners free, but revealed his treacherous nature by

arresting nearly 50 of the rescuers as, after the matter was settled, they

were returning to their homes. Among these was Major Boulton, whom he

condemned to be shot, but was persuaded by the earnest efforts of Mr.

Smith to recall the sentence and set him free. In the case of Thomas

Scott, however, the result was more dreadful. Ile was one of the prisoners

and for reasons that seem altogether insufficient was condemned to death.

In vain Mr. Smith and others interceded for him. The President was

immovable in his determination, and early in March the young man was put

to death. |