The Company's Indian policy—Character of officers—A race of hunters

—Plan of advances—Charges against the Company—Liquor

restriction—Capital punishment—Starving Indians—Diseased and

helpless—Education and religion—The age of missions— Sturdy Saulteaux—The

Muskegons—Wood Crees—Wandering Plain Crees—The Chipewyans—Wild

Assiniboines—Blackfeet Indians—Polyglot coast tribes—Eskimos—No Indian

war—No police—Pliable and docile—Success of the Company.

From time to time the opponents of the Company

have sought to find grounds for the overthrow of the licence to trade

granted by the Government of Britain over the Indian territories. One

of the most frequent lines of attack was in regard to the treatment of

the Indians by the fur traders. It may bo readily conceded that the

ideal of the Company's officials was in many cases not the highest.

The aim of Governor Simpson in his long reign of forty years was that

of a keen trader. A politic man, the leader of the traders when in

Montreal conformed to the sentiment of the city, abroad in the wilds

he did very little to encourage his subordinates to cultivate higher

aims among the natives. Often the missionary was found raising

questions very disturbing to the monopoly, and this brought the

Company officers into a hostile attitude to him. Undoubtedly in some

cases the missionaries were officious and unfair in their criticisms.

But, on the other hand, the men and officers of

the Company were generally moral. Men of education and reading the

officers usually were, and their sentiment was likely to be in the

right direction. The spirit of the monopoly—the golden character of

silence, and the need of being secretive and uncommunicative—was

instilled into every clerk, trapper, and trader.

But the tradition of the Company was to keep the

Indian a hunter. There was no effort to encourage the native to

agriculture or to any industry. To make a good collector of fur was

the chief aim. For this the Indian required no education, for this the

wandering habit needed to be cultivated rather than discouraged, and

for this it was well to have the home ties as brittle as possible.

Hence the tent and teepee were favoured for the Indian hunter more

than the log cottage or village house.

It was one of the most common charges against the

Company that in order to keep the Indian in subjection advances were

made on the catch of furs of the coming season, in order that, being

in debt, he might be less independent. The experience of the writer in

Red River settlement in former days leads him to doubt this, and

certainly the fur traders deny the allegation. The improvident or

half-breed Indian went to the Company's store to obtain all that he

could. The traders at the forts had difficulty in checking the

extravagance of their wards. Frequently the storekeeper refused to

make advances lost he should fail in recovering the value of the

articles advanced. Fitzgerald, a writer who took part in the agitation

of 1849, makes the assertion in the most flippant manner that to keep

the Indians in debt was the invariable policy of the Company. No

evidence is cited to support this statement, and it would seem to be

very hard to prove.

The same writer undertakes, along the line of

destructive criticism, to show that the Hudson's Bay Company does not

deserve the credit given it of discouraging the traffic in strong

drink, and asserts that "a beaver skin was never lost to the Company

for want of a pint of rum." This is a very grave charge, and in the

opinion of the writer cannot be substantiated. The Bishop of Montreal,

R. M. Ballantyne, and the agents of the missionary societies are said

either to have little experience or to be unwilling to tell on this

subject what they knew. This critic then quotes various statements of

writers, extending back in some cases thirty or forty years, to show

that spirituous liquors were sold by the Company. It is undoubted that

at times in the history of the fur trade, especially at the beginning

of the century, when the three Companies were engaged in a most

exacting competition, as we have fully shown, in several cases much

damage was done. On the Pacific Coast, too, eight or ten years before

this critic wrote, there was, as we have seen, excess. At other times,

also, at points in the wide field of operations, over half a

continent, intoxicating liquor was plentiful and very injurious, but

no feeling was stronger in a Hudson's Bay Company trader's mind than

that he was in a country without police, without military, without

laws, and that his own and his people's lives were in danger should

drunkenness prevail. Self-preservation inclined every trader to

prevent the use of spirits among the Indians. The writer is of opinion

that while there may have been many violations of sobriety, yet the

record of the Hudson's Bay Company has been on the whole creditable in

this matter.

The charges of executing capital punishment and

of neg lecting the Indians in years of starvation may be taken

together. The criticism of the people of Red River was that the

Company was weak in the execution of the penalties of the law. They

complained that the Company was uncertain of its powers and that the

hand of justice was chained. The marvel to an unprejudiced observer is

that the Company succeeded in ruling so vast a territory with so few

reprisals or executions. In the matter of assisting the Indians in

years of scarcity, it was the interest of the fur company to save the

lives of its trappers and workers. But those unacquainted with the

vast wastes of Rupert's Land and the Far North little know the

difficulties of at times obtaining food. The readers of Milton and

Cheadle's graphic story or our account of Robert Campbell's adventures

on the Stikine, know the hardships and the near approach to starvation

of these travellers. Dr. Cheadle, on a visit to Winnipeg a few years

ago, said to the writer that on his first visit the greatest

difficulty his party had was to secure supplies. There are years in

which game and fish are so scarce that in remote northern districts

death is inevitable for many. The conditions make it impossible for

the Company to save the lives of the natives. Relief for the diseased

and aged is at times hard to obtain. Small-pox and other epidemics

have the most deadly effect upon the semi-civilized people of the

far-off hunter's territory.

The charge made up to 1849 that the Hudson's Bay

Company had done little for the education and religious training of

the Indians was probably true enough. Outside of Red River and British

Columbia they did not sufficiently realize their responsibility as a

company. Since that time, with the approval and co-operation in many

ways of the Company, the various missionary societies have grappled

with the problem. The Indians about Hudson Bay, on Lake Winnipeg, in

the Mackenzie River, throughout British Columbia, and on the great

prairies of Assiniboia, are to-day largely Christianized and receiving

education.

The Saulteaux, or Indians who formerly lived at

Sault Ste. Marie, but wandered west along the shore of Lake Superior

and even up to Lake Winnipeg, are a branch of the Algonquin 0jibeways.

Hardy and persevering, most conservative in preserving old customs,

hard to influence by religious ideas, they have been pensioners of the

Hudson's Bay Company, but their country is very barren, and they have

advanced but little.

Very interesting, among their relations of

Algonquin origin, are the Muskegons, or Swampy Crees, who have long

occupied the region around Hudson Bay and have extended inland to Lake

Winnipeg. Docile and peaceful, they have been largely influenced by

Christianity. Under missionary and Company guidance they have gathered

around the posts, and find a living on the game of the country and in

trapping the wild animals.

Related to the Muskegons are the Wood Crees, who

live along the rivers and on the belts of wood which skirt lakes and

hills. They cling to the birch-bark wigwam, use the bark canoe, and

are nomadic in habit. They may be called the gipsies of the West, and

being in scattered families have boon little reached by better

influences.

Another branch of the Algonquin stock is the

Plain Crees. These Indians are a most adventurous and energetic

people. Leaving behind their canoes and Huskie dogs, they obtained

horses and cayuses and hied them over the prairies. Birch-bark being

unobtainable, they made their tents, better fitted for protecting them

from the searching winds of the prairies and the cold of winter, from

tanned skins of the buffalo and moose-deer. For seven hundred miles

from the mouth of the Saskatchewan they extend to the foot hills of

the Rocky Mountains. Meeting in their great camps, seemingly

untameable as a race of plain hunters, they were, up to the time of

the transfer to Canada, almost untouched by missionary influence, but

in the last thirty years they have been placed on reserves by the

Canadian Government and are in almost all cases yielding to

Christianizing agencies.

North of the country of the Crees live tribes

with very wide connections. They call themselves "Tinné" or "People,"

but to others they are known as Chipewyans, or Athabascans. They seem

to be less copper-coloured than the other Indians, and are docile in

disposition. This nation stretches from Fort Churchill, on Hudson Bay,

along the English River, up to Lake Athabasca, along the Peace River

into the very heart of the Rocky Mountains, and even beyond to the

coast. They have proved teachable and yield to ameliorating

influences.

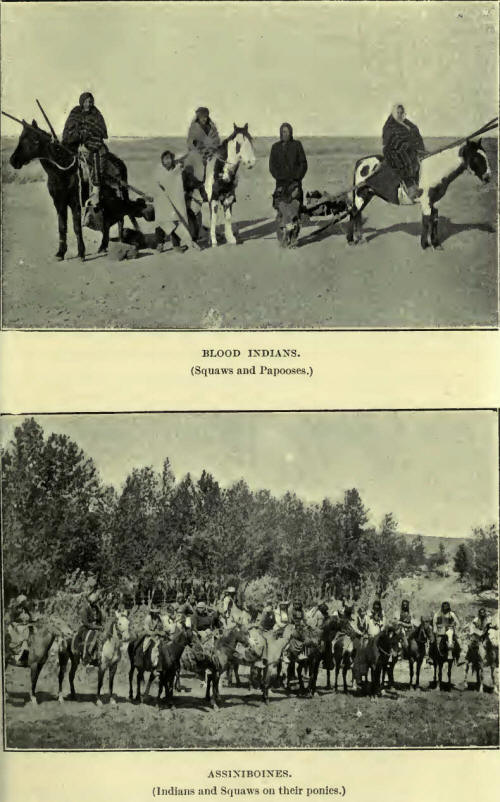

Probably the oldest and best known name of the

interior of Rupert's Land, the name after which Lord Selkirk called

his Colony of Assiniboia, is that belonging to the Wild Assiniboines

or Stony River Sioux. The river at the mouth of which stands the city

of Winnipeg was their northern boundary, and they extended southward

toward the great Indian confederacy of the Sioux natives or Dakotas,

of which indeed they were at one time a branch. Tall, handsome, with

firmly formed faces, agile and revengeful, they are an intelligent and

capable race. These Indians, known familiarly as the "Stonies," have

greatly diminished in numbers since the time of Alexander Henry, jun.,

who describes them fully. In later years they have been cut down with

pulmonary and other diseases, and are to-day but the fragment of a

great tribe. They have long been friendly with the Plain Crees, but

are not very open to Christianity, though there are one or two small

communities which are exceptions in this respect.

Very little under Hudson's Bay Company control

were the Blackfoot nation, along the foot hills of the Rocky

Mountains, ear the national boundary. Ethnically they are related to

the Crees, but they have always been difficult to approach. Living in

large camps during Hudson's Bay Company days, they spent a wild,

happy, comfortable life among the herds of wandering buffalo of their

district. Since the beginning of the Canadian r6gime they have become

more susceptible to civilizing agencies, and live in great reserves in

the south-west of their old hunting grounds.

A perfect chaos of races meets us among the

Indians of British Columbia and Alaska, and their language is

polyglot. Seemingly the result of innumerable immigrations from

Malayan and Mongolian sources in Asia, they have come at different

times. One of the best known tribes of the coast is the Haidas,

numbering some six thousand souls. The Nutka Indians occupy Vancouver

Island, and have many tribal divisions. To the Selish or Flatheads

belong many of the tribes of the Lower Fraser River, while the

Shushwaps hold the country on the Columbia and Okanagan Rivers.

Mention has been made already of the small but influential tribe of

Chinooks near the mouth of the Columbia River.

While differing in many ways from each other, the

Indians of the Pacific Coast have always been turbulent and excitable.

From first to last more murders and riots have taken place among them

than throughout all the vast territory held by the Hudson's Bay

Company east of the Rocky Mountains. While missionary zeal has

accomplished much among the Western Coast Indians, yet the "bad

Indian" element has been a recognized and appreciable quantity among

them so far as the Company is concerned.

Last among the natives who have been under

Hudson's Bay Company influence are the Eskimos or Innuits of the Far

North. They are found on the Labrador Coast, on Coppermine River, on

the shore of the Arctic Sea, and on the Alaskan peninsula. Dressed in

sealskin clothing and dwelling in huts of snow, hastening from place

to place in their sledges drawn by wolf-like dogs called "Eskies" or

"Huskies," these people have found themselves comparatively

independent of Hudson's Bay Company assistance. Living largely on the

products of the sea, they have shown great ingenuity in manufacturing

articles and implements for themselves. The usual experience of the

Company from Ungava, through the Mackenzie River posts, and the

trading houses in Alaska has been that they were starved out and were

compelled to give up their trading houses among them. Little has been

done, unless in the Yukon country, to evangelize the Eskimos.

The marvel to the historian, as he surveys the

two centuries and a quarter of the history of the Hudson's Bay

Company, is their successful management of the Indian tribes. There

has never been an Indian war in Rupert's Land or the Indian

territories—nothing beyond a temporary emeute or incidental outbreak.

Thousands of miles from the nearest British garrison or soldier, trade

has been carried on in scores and scores of forts and factories with

perfect confidence. The Indians have always respected the "Kingchauch

man." He was to them the representative of superior ability and

financial strength, but more than this, he was the embodiment of

civilization and of fair and just dealing. High prices may have been

imposed on the Indians, but the Company's expenses were enormous.

There are points among the most remote trading posts from which the

returns in money were not possible in less than nine years from the

time the goods left the Fenchurch Street or Lime Street warehouses.

With all his keen bargaining and his so-called exacting motto, "Pro

pelle cutem," the trader was looked upon by the Indians as a

benefactor, bringing into his barren, remote, inhospitable home the

commodities to supply his wants and make his life happier. While the

Indians came to recognize this in their docile and pliable acceptance

of the trader's decisions, the trader also became fond of the Red man,

and many an old fur trader freely declares his affection for his

Indian ward, so faithful to his promise, unswerving in his attachment,

and celebrated for never forgetting a kindness shown him.

The success of the Company was largely due to

honourable, capable, and patient officers, clerks, and employes, who

with tact and Justice managed their Indian dependents, many of whom

rejoiced in the title of "A Hudson's Bay Company Indian."