The

North-West Passage

again—Lieut. John

Franklin's land expedition

—Two lonely

winters—Hearne's mistake

corrected—Franklin's

second journey—Arctic sea

coast explored—Franklin

knighted— Captain John

Ross by sea—Discovers

magnetic pole—Magnetic

needle nearly

perpendicular—Back seeks

for Ross—Dease and Simpson

sent by Hudson's Bay

Company to explore—Sir

John in Erebus and

Terror—The Paleocrystic

Sea—Franklin never

returns—Lady Franklin's

devotion—The historic

search—Dr. Rae secures

relics—Captain McClintock

finds the cairn and

written record—Advantages

of the search.

The

British people were ever

on the alert to have their

famous sea captains

explore new seas,

especially in the line of

the discovery of the

North-West Passage. From

the time of Dobbs, the

discomfiture of that

bitter enemy of the

Hudson's Bay Company had

checked the advance in

following up the

explorations of Davis and

Baffin, whose names had

become fixed on the icy

sea channels of the North.

Captain Phipps, afterwards

Lord Mulgrave, had been

the last of the great

captains who had taken

part in the spasm of

north-west interest set

agoing by Dobbs. Two

generations of men had

passed when, in 1817, the

quest for the North-West

Passage was taken up by

Captain William Scoresby.

Scoresby advanced a fresh

argument in favour of a

new effort to attain this

long-harboured dream of

the English captains. He

maintained that a change

had taken place in the

seasons, and the position

of the ice was such as

probably to allow a

successful voyage to be

made from Baffin's Bay to

Behring Strait.

Sir

John Barrow with great

energy advocated the

project of a new

expedition, and Captain

John Ross and Edward Parry

were despatched to the

northern seas. Parry's

second expedition enabled

him to discover Fury and

Hecla Strait, to pass

through Lancaster Strait,

and to name the

continuation of it Barrow

Strait, after the great

patron of northern

exploration.

FRANKLIN'S LAND EXPEDITION

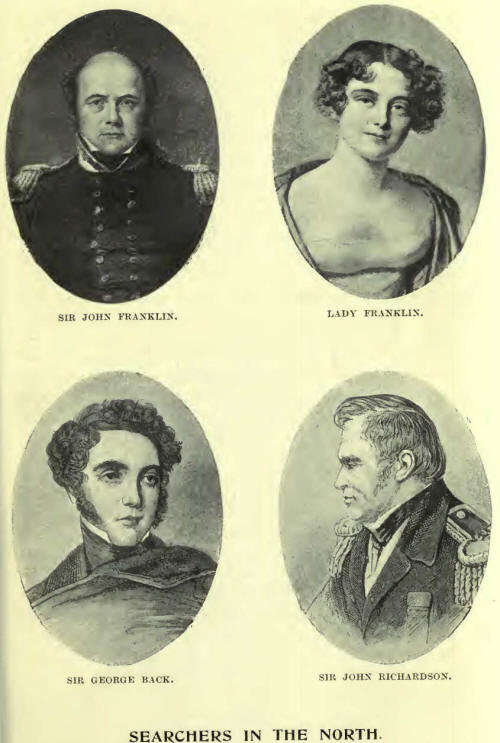

Meanwhile John Franklin

was despatched to cross

the plains of Rupert's

Land to forward Arctic

enterprise. This notable

man has left us an

heritage of undying

interest in connection

with this movement. A

native of Lincolnshire, a

capable and trusted naval

officer, who had fought

with Nelson at Copenhagen,

who had gone on an Arctic

voyage to Spitzbergen, and

had seen much service

elsewhere, he was

appointed to command the

overland expedition

through Rupert's Land to

the Arctic Sea, while

Lieutenant Parry sought,

as we have seen, the

passage with two vessels

by way of Lancaster Sound.

Accompanied by a

surgeon—Dr. Richardson—two

midshipmen, Back and Hood,

and a few Orkneymen,

Lieutenant Franklin

embarked from England for

Hudson Bay in June, 1819.

Wintering for the first

season on the

Saskatchewan, the party

were indebted to the

Hudson's Bay Company for

supplies, and reached Fort

Chipewyan in about a year

from the time of their

departure from England.

The second winter was

spent by the expedition on

the famous barren grounds

of the Arctic slope. Their

fort was called Fort

Enterprise, and the party

obtained a living chiefly

from the game and fish of

the region. In the

following summer the

Franklin party descended

the Coppermine River to

the Arctic Sea. Here

Hearne's mistake of four

degrees in the latitude

was corrected and the

latitude of the mouth of

the Coppermine River fixed

at 67° 48' N. Having

explored the coast of the

Arctic Sea eastward for

six degrees to Cape

Turnagain and suffered

great hardships, the

survivors of the party

made their return Journey,

and reached Britain after

three years' absence.

Franklin was given the

rank of captain and

covered with social and

literary honours.

Three years after his

return to England, Captain

Franklin and his old

companions went upon their

second journey through

Rupert's Land. Having

reached Fort Chipewyan,

they continued the journey

northward, and the winter

was spent at their

erection known as Fort

Franklin, on Great Bear

Lake. Here the party

divided, one portion under

Franklin going down the

Mackenzie to the sea, and

coasting westward to

Return Reef, hoping to

reach Captain Cook's icy

cape of 1778. In this they

failed. Dr. Richardson led

the other party down the

Mackenzie River to its

mouth, and then, going

eastward, reached the

mouth of the Coppermine,

which he ascended. By

September both parties had

gained their rendezvous,

Fort Franklin, and it was

found that unitedly they

had traced the coast line

of the Arctic Sea through

thirty-seven degrees of

longitude. On the return

of the successful

adventurer, after an

absence of two years, to

England, he was knighted

and received the highest

scientific honours.

CAPTAIN JOHN ROSS BY SEA.

When the British people

become roused upon a

subject, failure seems but

to whet the public mind

for new enterprise and

greater effort. The

North-West Passage was now

regarded as a possibility.

After the coast of the

Arctic Ocean had been

traced by the

Franklin-Richardson

expedition, to reach this

shore by a passage from

Parry's Fury and Hecla

Strait seemed feasible.

Two years after the return

of Franklin from his

second overland journey,

an expedition was fitted

out by a wealthy

distiller, Sheriff Felix

Booth, and the ship, the

Victory, provided by him,

was placed under the

command of Captain John

Ross, who had already

gained reputation in

exploring Baffin's Bay.

Captain Ross was ably

seconded in his expedition

by his nephew, Captain

James Ross. Going by

Baffin's Bay and through

Lancaster Sound, Prince

Regent's Inlet led Ross

southward between Cockburn

Island and Somerset North,

into an open sea called

after his patron, Gulf of

Boothia, on the west side

of which he named the

newly-discovered land

Boothia Felix. He even

discovered the land to the

west of Boothia, calling

it King William Land. His

ship became embedded in

the ice. After four

winters in the Arctic

regions he was rescued by

a whaler in Barrow Strait.

One of the most notable

events in this voyage of

Ross's was his discovery

of the North Magnetic Pole

on the west side of

Boothia Felix. During his

second winter (1831)

Captain Ross determined to

gratify his ambition to be

the discoverer of the

point where the magnetic

needle stands vertically,

as showing the centre of

terrestrial magnetism for

the northern hemisphere.

After four or five days'

overland journey, with a

trying headwind from the

north-west, he reached the

sought-for point on June

1st. We deem it only just

to state the discovery in

the words of the veteran

explorer himself :—

"The land at this place is

very low near the coast,

but it rises into ridges

of fifty or sixty feet

high about a mile inland.

We could have wished that

a place so important had

possessed more of mark or

note. It was scarcely

censurable to regret that

there was not a mountain

to indicate a spot to

which so much interest

must ever be attached ;

and I could even have

pardoned any one among us

who had been so romantic

or absurd as to expect

that the magnetic pole was

an object as conspicuous

and mysterious as the

fabled mountain of Sinbad,

that it was even a

mountain of iron, or a

magnet as large as Mont

Blanc. But Nature had here

erected no monument to

denote the spot which she

had chosen as the centre

of one of her great and

dark powers; and where we

could do little ourselves

towards this end, it was

our business to submit,

and to be content in

noting in mathematical

numbers and signs, as with

things of far more

importance in the

terrestrial system, what

we could ill distinguish

in any other manner.

"The necessary

observations were

immediately commenced, and

they were continued

throughout this and the

greater part of the

following day. . . . The

amount of the dip, as

indicated by my

dipping-needle, was 89°

59', being thus within one

minute of the vertical;

while the proximity at

least of this pole, if not

its actual existence where

we stood, was further

confirmed by the action,

or rather by the total

inaction, of several

horizontal needles then in

my possession. ... There

was not one which showed

the slightest effort to

move from the position in

which it was placed.

"As soon as I had

satisfied my own mind on

this subject, I made known

to the party this

gratifying result of all

our joint labours; and it

was then that, amidst

mutual congratulations, we

fixed the British flag on

the spot, and took

possession of the North

Magnetic Pole and its

adjoining territory, in

the name of Great Britain

and King William the

Fourth. We had abundance

of material for building

in the fragments of

limestone that covered the

beach ; and we therefore

erected a cairn of some

magnitude, under which we

buried a canister

containing a record of the

interesting fact, only

regretting that we had not

the means of constructing

a pyramid of more

importance and of strength

sufficient to withstand

the assaults of time and

of the Esquimaux. Had it

been a pyramid as large as

that of Cheops I am not

quite sure that it would

have done more than

satisfy our ambition under

the feelings of that

exciting day. The latitude

of this spot is 70° 5' 17"

and its longitude 96° 46'

45"."

Thus much for the magnetic

pole. This pole is almost

directly north of the city

of Winnipeg, and within

less than twenty degrees

of it. One of Lady

Franklin's captains—

Captain Kennedy, who

resided at Red

River—elaborated a great

scheme for tapping the

central supply of

electricity of the

magnetic pole, and

developing it from

Winnipeg as a source of

power.

SIR GEORGE BACK, THE

EXPLORER.

In the third year of

Captain Ross's expedition

his protracted absence

became a matter of public

discussion in Britain. Dr.

Richardson, who had been

one of Franklin's

followers, offered to take

charge of an overland

expedition in search of

Ross, but his proposition

was not accepted. Mr.

Ross, a brother of Sir

John and father of Captain

James Ross, was anxious to

find an officer who would

take charge of a relief

expedition, and the

British Government

favoured the enterprise.

Captain George Back, one

of the midshipmen who had

accompanied Franklin, was

favourably regarded for

the important position.

The Hudson's Bay Company

was in sympathy with the

exploration of its Arctic

possessions and gave every

assistance to the project.

Nicholas Garry, the

Deputy-Governor of the

Company, ably supported

it; and the British

Government at last gave

its consent to grant two

thousand pounds, provided

the Hudson's Bay Company

would furnish, according

to its promise, the

supplies and canoes free

of charge, and that

Captain Ross's friends

would contribute three

thousand pounds.

Captain Back cordially

accepted the offer to

command the expedition,

and his orders from the

Government were to find

Captain Ross, or any

survivors or survivor of

his party; and,

"subordinate to this, to

direct his attention to

mapping what remains

unknown of the coasts

which he was to visit, and

make such other scientific

observations as his

leisure would admit."

In 1833 Captain Back

crossed the Atlantic,

accompanied by a surgeon,

Dr. Richard King, and at

Montreal obtained a party

of four regulars of the

Royal Artillery. Pushing

on by the usual route, he

reached Lake Winnipeg, and

thence by light canoe

arrived at Fort Resolution

on Great Slave Lake in

August. He wintered at

Fort Reliance, near the

east end of Great Slave

Lake, which was

established by Roderick

McLeod, a Hudson's Bay

Company officer, who had

received orders to assist

the expedition. Before

leaving this point a

message arrived from

England that Captain Ross

was safe. Notwithstanding

this news, in June of the

following year Back and

his party crossed the

country to Artillery Lake,

and drew their boats and

baggage in a most toilsome

manner over the ice of

this and three other

lakes, till the Great Fish

River was reached and its

difficult descent begun.

On July 30th the party

encamped at Cape Beaufort,

a prominent point of the

inlet of the Arctic Ocean

into which the Great Fish

River empties. The

expedition again descended

the river and returned to

England, where it was well

received, and Captain Back

was knighted for his pluck

and perseverance. An

expedition under Back in

the next year, to go by

ship to Wager Bay and then

to cross by portage the

narrow strip of land to

the Gulf of Boothia, was a

failure, and the party

with difficulty reached

Britain again.

A HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY

EXPEDITION — DEASE AND

SIMPSON.

Dr. Richard King, who had

been Back's assistant and

surgeon, now endeavoured

to organize an expedition

to the Arctic Ocean by way

of Lake Athabasca and

through a chain of lakes

leading to the Great Fish

River. This project

received no backing from

the British Government or

from the Hudson's Bay

Company. The Company now

undertook to carry out an

expedition of its own. The

reasons of this are stated

to have been—(1) The

interest of the British

public in the effort to

connect the discoveries of

Captains Back and Ross;

(2) They are said to have

desired a renewal of their

expiring lease for

twenty-one years of the

trade of the Indian

territories ; (3) The fact

was being pointed out, as

in former years, that

their charter required the

Company to carry on

exploration.

In 1836 the Hudson's Bay

Company in London decided

to carrying out the

expedition, and gave

instructions to Governor

Simpson to organize and

despatch it. At Norway

House, at the meeting of

the Governor and officers

of that year, steps were

taken to explore the

Arctic Coast. An

experienced Hudson's Bay

Company officer, Peter

Warren Dease, and with him

an ardent young man,

Thomas Simpson, a relation

of the Governor, was

placed in charge.

The party, after various

preparations, including a

course of mathematics and

astronomy received by

Thomas Simpson at Red

River, made its departure,

and Fort Chipewyan was

reached in February, where

the remainder of the

winter was spent. As soon

as navigation opened, the

descent of the Mackenzie

River was made to the

mouth. The party then

coasting westward on the

Arctic Ocean, passed

Franklin's "Return Reef,"

reached Boat Extreme, and

Simpson made a foot

journey thence to Cape

Barrow.

Having returned to the

mouth of the Mackenzie

River, the Great Bear

Lake, where Fort

Confidence had been

erected by the advance

guard of the party, was

reached.

The winter was passed at

this point, and in the

following spring the

expedition descended the

Copper-mine River, and

coasting eastward along

the Polar Sea, reached

Cape Turnagain in August.

Returning and ascending

the Coppermine for a

distance, the party

halted, and Simpson made a

land journey eastward to

new territory which he

called Victoria Land, and

erected a pillar of

stones, taking possession

of the country, "in the

name of the Honourable

Company, and for the Queen

of Great Britain." Their

painful course was then

retraced to Fort

Confidence, where the

second winter was spent.

On the opening of spring,

the Company descended to

the coast to carry on

their work. Going

eastward, they, after much

difficulty, reached new

ground, passed Dease's

Strait, and discovered

Cape Britannia.

Taking

two years to return,

Simpson arrived at Fort

Garry, and disappointed at

not receiving further

instructions, he joined a

freight party about to

cross the plains to St.

Paul, Minnesota. While on

the way he was killed,

either by his half-breed

companions or by his own

hand. His body was brought

back to Fort Garry, and is

buried at St. John's

cemetery.

The Hudson's Bay Company

thus made an earnest

effort to explore the

coast, and through its

agents, Dease and Simpson,

may be said to have been

reasonably successful.

THE SEARCH FOR FRANKLIN.

After the return of Sir

John Franklin from his

second overland expedition

in Rupert's Land, Sir John

was given the honourable

position of

Lieutenant-Governor of

Tasmania, and on his

coming again to England,

was asked by the Admiralty

to undertake a sea voyage

for the purpose of finding

his way from Lancaster

Sound to Behring's Strait.

Sir John accepted the

trust, and his popularity

led to the offer of

numerous volunteers, who

were willing to undertake

the hazards of the

journey. Two excellent

vessels, the Erebus and

Terror, well fitted out

for the journey, were

provided, and his

expedition started with

the most glowing hopes of

success, on May 19th,

1845. Many people in

Britain were quite

convinced that the

expectation of a

north-west passage was now

to be realized.

We know now only too well

the barrier which lay in

Franklin's way. Almost

directly north-east of the

mouth of Fish River, which

Back and Simpson had both

found, there lies a vast

mass of ice, which can

neither move toward

Behring's Strait on

account of the shallow

opening there, or to

Baffin's Bay on account of

the narrow and tortuous

winding of the channels.

This, called by Sir George

Nares the Paleocrystic

Sea, we are now aware bars

the progress of any ship.

Franklin had gone down on

the west side of North

Somerset and Boothia, and

coming against the vast

barrier of the

Paleo-crystic Sea, had

been able to go no

further.

Two years after the

departure of the

expedition from which so

much was expected, there

were still no tidings.

Preparations were made for

an expedition to rescue

the adventurers, and in

1848 the first party of

relief sailed.

For the next eleven years

the energy and spirit and

liberality of the British

public were something

unexampled in the annals

of public sympathy.

Regardless of cost or

hazard, not less than

fifteen expeditions were

sent out by England and

the United States on their

sad quest. Lady Franklin,

with a heroism and skill

past all praise, kept the

eye of the nation steadily

on her loss, and

sacrificed her private

fortune in the work of

rescue. We are not called

upon to give the details

of these expeditions, but

may refer to a few notable

points.

The Hudson's Bay Company

at once undertook a

journey by land in quest

of the unfortunate

navigator. Dr. Richardson,

who had gone on Franklin's

first expedition, along

with a well-known Hudson's

Bay Company officer, Dr.

Rae, scoured the coast of

the Arctic Sea, from the

mouth of the Mackenzie to

that of the Coppermine

River. For two years more,

Dr. Rae continued the

search, and in the fourth

year (1851) this facile

traveller, by a long

sledge journey in spring

and boat voyage in summer,

examined the shores of

Wollaston and Victoria

Land.

A notable expedition took

place in the sending out

by Lady Franklin herself

of the Prince Albert

schooner, under Captain

Kennedy, who afterwards

made his home in the Red

River settlement. His

second in command was

Lieutenant Bellot, of the

French Navy, who was a

plucky and shrewd

explorer, and who, on a

long sledge journey,

discovered the Strait

which bears his name

between North Somerset and

Boothia.

The names of McClure,

Austin, Collinson, Sir

Edmund Belcher, and

Kellett stand out in bold

relief in the efforts—

fruitless in this

case—made to recover

traces of the unfortunate

expedition.

The first to come upon

remains of the Franklin

expedition was Dr. John

Rae, who, we have seen,

had thoroughly examined

the coast along the Arctic

Ocean. The writer well

remembers meeting Dr. Rae

many years after in the

city of Winnipeg and

hearing his story.

Rae was a lithe, active,

enterprising man. In 1853,

he announced that the

drawback in former

expeditions had been the

custom of carrying a great

stock of provisions and

useless impedimenta, and

so under Hudson's Bay

Company auspices he

undertook to go with gun

and fishing tackle up the

west coast of Hudson Bay.

This he did, ascended

Chesterfield Inlet, and

wintered with eight men at

Repulse Bay.

In the next season he made

a remarkable journey of

fifty-six days, and

succeeded in connecting

the discoveries of Captain

James Ross with those of

Dease and Simpson, proving

King William Land to be an

island. Rae discovered on

this Journey plate and

silver decorations among

the Eskimos, which they

admitted had belonged to

the Franklin party. Dr.

Rae was awarded a part of

the twenty thousand pounds

reward offered by the

Imperial Government.

The British people could

not, however, be satisfied

until something more was

done, and Lady Franklin,

with marvellous

self-devotion, gave the

last of her available

means to add to the public

subscription for the

purchase and fitting out

of the little yacht Fox,

which, under Captain

Leopold McClintock, sailed

from Aberdeen in 1857.

Having in less than two

years reached Bellot

Strait, McClintock's party

was divided into three

sledging expeditions. One

of them, under Captain

McClintock, was very

successful, obtaining

relics of the lost

Franklin and his party and

finding a cairn which

contained an authoritative

record of the fortunes of

the company for three

years. Sir John had died a

year before this record

was written. Captain

McClintock was knighted

for his successful effort

and the worst was now at

last known.

The attempt of Sir John

and the efforts to find

him reflect the highest

honour on the British

people. And not only

sentiment, but reason was

satisfied. As had been

said, "the catastrophe of

Sir John Franklin's

expedition led to seven

thousand miles of coast

line being discovered, and

to a vast extent of

unknown country being

explored, securing very

considerable additions to

geographical knowledge.

Much attention was also

given to the collection of

information, and the

scientific results of the

various search expeditions

were considerable."