| Continued from

Part 1...

Further evidence in 1820 of the falling

off in Leith’s Baltic trade appears in the application of James

Anderson, a cooper and fish-curer of Edinburgh, who wrote ‘that

business [i.e. fish-curing] has been very dull in Edinburgh and Leith in

late years’. Cured and barrelled herrings had long been a staple

Scottish export to the Baltic. Yet another indication of the decline of

Leith’s trade with the Baltic and the north German ports is found in

the applications of several merchants who had been in business in

Hamburg, and who had returned to Edinburgh and Leith when their trade

there fell off badly after the Elbe Mania of 1813-14. The effect of

these setbacks to Leith’s trade on the local shipbuilding industry is

seen, too, in the applications made on behalf of David McLean in 1822,

and by R. D. and William Cuninghame in 1828. The latter applicants,

father and son, were in business on a considerable scale in Leith, and

subsequently established themselves in the same line in Sydney. Certain

manufactures were also affected particularly badly, for in 1820, 1821,

and 1822, a number of silk and shawl manufacturers in the capital made

application, instancing the ‘considerable depression of trade’, and

several other Leith and Edinburgh merchants described themselves as ‘unfortunate

in business’, or referred to ‘the destroyed state of commerce in the

district’.

It was from the

mercantile class of the area of Edinburgh and Leith that the most

imposing ‘group applications’ came, like the petition forwarded by

William Arbuthnot, Lord Provost of Edinburgh, in January 1822 from eight

men of property, all heads of families, who wished to go out ‘as a

group of about sixty persons, proposing to take with us a surgeon, a

schoolmaster, and two or three artificers, servants, etc.’ Their aim

was to settle together ‘for our mutual protection’, and the list was

headed by three prominent merchants, a teacher, and a lawyer. Commending

them to the London authorities, the Lord Provost stated that they were

taking with them considerable property, and were ‘experienced active

men’.

In like fashion R.

Towers, another Edinburgh merchant, had his application recommended by

‘the whole Town Council of Stirling’, his native city, and forwarded

by Robert Downie, a local landowner and Member of Parliament. Thomas

Callam’s approach in 1820 on behalf of the Leith and Edinburgh

merchants who wanted approval to carry on their trading activities in

the colonies was apparently successful, and it is clear from several

subsequent applications that others in the mercantile community of the

capital and its port were anxious to follow the example of Callam and

his group.

The emigrating merchants

from other areas also included men of substance. An example was

Alexander Mackenzie of Cromarty, who arrived in Sydney, aged 53, in

1822, with sufficient capital to qualify for a grant of 2,000 acres near

Bathurst in the following year. As secretary and cashier to the Bank of

New South Wales in the 1820s, and first President of the Bathurst Bank

(1835), he took part in many pastoral and mercantile ventures. In 1823

Peter Grant of Leith, a substantial young merchant who was to become one

of the leading traders in Hobart, chartered the ship Heroine, a

large vessel of 450 tons, and loaded it with goods valued at £3,000, at

the same time applying for a grant of land; and in 1824 Frederick

Schultze, member of a well-known family of Leith merchants, took out

£1,500 in goods as stock with which to set up in business in Hobart.

Similarly, the Mosman brothers from Lesmahagow, who went out in the

chartered brig Civilian in 1828, were sufficiently wealthy to

purchase several ships on arrival in Sydney, and to establish a whaling

station, complete with workshops, stores, and trying-houses, on the

northern shore of Port Jackson.

It is worth noting that

most of the merchants who embarked for the colonies in 1820—4 still

possessed considerable wealth. Not content to weather out the economic

storm at home, they were adventurous enough to hazard their fortunes in

what must have seemed to many of them an exciting new field for

enterprise. Men like Schultze, Grant, and Callam were far from being

ruined merchants, and David Murray, a prominent wine merchant with

stores in Leith and a warehouse in Edinburgh who applied in March 1824, stated that he had engaged ‘three tradesmen with their families’ for Van Diemen’s Land, in addition to domestic servants and two nephews to assist him in trading and agricultural activities in the colony. In the same year William Young, merchant in Leith, gave his capital as £2,000, and stated another £500 on his son’s account in applying for an additional grant for the youth.

Among the five Leith or Edinburgh merchants who applied in the general rush of 1820 was Thomas

Wyld, a nephew of James Wyld of Gilston, prominent wine merchant and shipowner of Leith, and a founder and director of the Commercial Bank. This Australian contact may have been instrumental in turning the attention of Wyld and his business associates to Australia, and in

influencing them in favour of the project of forming an Australian company in Leith two years later.

This was, essentially, a middle-class emigration, and a report in the

Edinburgh Evening Courant of August 1821 brings this out very clearly:

There is now in Leith Roads a fine ship, the

Castle Forbes—destined for New South Wales, being the third vessel of her size which, in the course of twelve months, has been fitted out at this port under the direction of Mr.

Broadfoot, broker. . . . The Castle Forbes will take out 150 emigrants, nearly 100 of whom are cabin passengers, comprising capitalists of opulence and high respectability. We regret that the commerce and agriculture of our own country are no longer considered worthy objects of their speculation.

While it is apparent from the surge of applications from merchants in 1820 that the cause of the movement was largely economic, the effect of the publicizing work done by James Dixon and John Broadfoot of Leith is also clearly indicated. Both had inserted advertisements in the Scottish press offering passages and stating the opportunities for settlers by March 1820, and the Colonial Office, too, had published notices. A few weeks later the Edinburgh

Scotsman came out strongly in favour of emigration with a front-page editorial article, a most unequivocal statement in favour of this remedy for ‘redundant population’.

‘We are surprised’, observed the editor, ‘that there should be so

much reluctance to have recourse to this remedy’, and he urged that it

should be directed to all available fields, including Australia, whether

within or outside the Empire, ‘to the United States, Brazil, Buenos

Ayres, or to Canada, New Holland or the Cape’.’ The more widely read

and less ‘advanced’ Edinburgh Evening Courant did not indulge

in editorial articles of this kind, but by the tone of its reports it,

too, regarded the emigration favourably. If these important newspapers

are any guide to the state of opinion in and around the capital,

emigration was very much a current topic, as a solution not only for

working-class distress, but for the frustrations and difficulties of the

middle class as well.

In March 1820, just

before the Shelton sailed on the first direct voyage between

Scotland and Australia, Dixon was in Glasgow, where he was in touch with

a group of merchants who had ‘suffered losses in trade’, and had

apparently interested them in Australia, for he wrote to Goulburn on 11

March asking that they be sent information about the ‘indulgences

granted to settlers’, probably in order to encourage them. Although

there were comparatively few Glasgow merchants among the settlers of the

1820s, they included some very substantial and enterprising people.

Proportionately, they figure more prominently in the later 1820s than in

the earlier years when the emigration was at its height— perhaps an

indication that Glasgow and the west were less severely affected by the

stringencies of 1819—24 than the capital and its environs. Some had

long been considering emigration to Australia, like John Forlong,

Glasgow merchant, who sent his two sons to Saxony ‘to work in the best

sorting-houses of Germany.. . so as to be fully instructed in the

stapling of fine wools. . .‘ and to collect flocks ‘of the purest

Electoral blood’. Forlong sent out his elder son in 1827—8 and

applied for grants for the younger son and himself in 1829.

The great number of

bankruptcies in and around Glasgow in 1819 and 1820, when many who had

speculated in cotton were ruined owing to the fall in its price, seems

to have had little effect in stimulating emigration to Australia from

that quarter, and James Dixon’s encouragements were apparently in

vain. The United States, and even the South American republics and

Canada, were the fields that attracted the Glasgow emigrants and traders

in the early 1820s. By April 1821 the Glasgow Agricultural Society was

sending from the Clyde shiploads of settlers for Upper Canada, and

Kirkman Finlay and other shipowners were urging their fellow townsmen in

Glasgow to heed the good reports that were appearing in the press

concerning the Illinois and the British provinces in North America. The Dundee,

Perth and Cupar Advertiser reported in May that practically all of

the 442 emigrants in the most recent exodus from Greenock for Quebec

were drawn from Glasgow and the adjacent counties of Lanark and Renfrew.

It was only after the collapse of several commercial ventures in the

Americas at the close of 1825 that a Glasgow paper condemned the

practice of ‘looking for exhaustless stores in places where they are

not to be found.. . and ignoring the colonies (including Australia) with

which we might yet carry on a sure and beneficial trade’.

The emigration from other

populous parts of the West Country was likewise directed towards North

America. In April 1819 the Glasgow Herald reported that no fewer

than three sizeable vessels were lying at Dumfries, ready to sail for

New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, and that 517 persons had already

embarked, ‘the great proportion of them from Annandale, Wigtown and

the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright. . . many of them small farmers who have

yielded to the flattering statements of such writers as Birkbeck’.

Several ships also sailed from Leith in 1819 for Halifax and Quebec, but

by far the greater number of the emigrants to North America were from

Glasgow, the south-west Lowlands, and the western Highlands. This

movement was promoted by ‘the gentlemen of Renfrew and Lanarkshire’,

who, in 1821, were making ‘earnest and repeated entreaties’ to the

Government for a £10 bounty on passages. Their approaches were

fruitless as regards bounties, but they did manage to secure an official

assurance that there would be land grants, with implements supplied, for

the lesser folk who emigrated to Upper Canada.

The flow of West Country

and Highland emigration to North America was constant throughout the

1820s, and as far as the mass of intending emigrants among the working

classes in the west of Scotland were concerned, the passage rates to

Australia were prohibitive. ‘The great rage for emigration in Paisley’

among the handloom weavers, reported by the Tasmania in 1827, and

the enthusiasm generated by a number of emigration societies in and

around Glasgow, had little effect in swelling the flow of working-class

people to Van Diemen’s Land or New South Wales.

J. R. McCulloch, writing

in the Edinburgh Review when the controversy on assisted

emigration was at its height, commended the Canadian schemes and

described the North American colonies as ‘the most practicable breach’

for large-scale working-class emigration.

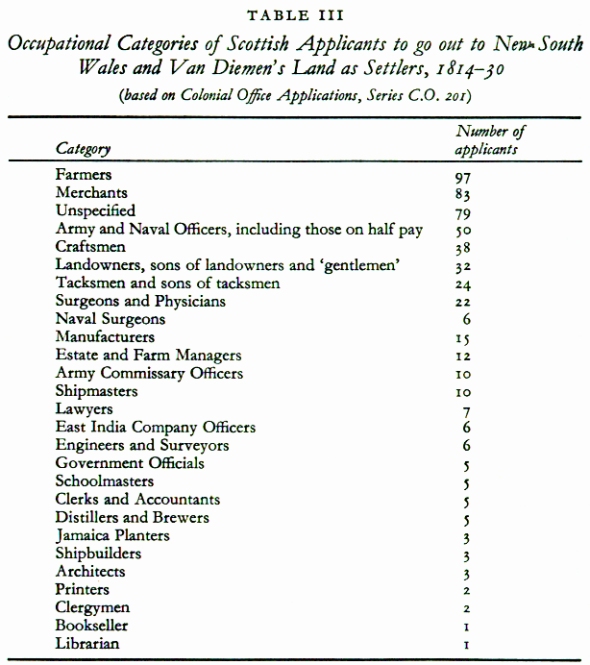

The occupations of the

applicants of 1820—30, and their geographical distribution, confirm

the accepted notions about the economic state of Scotland at that time.

There is ample evidence of the effects of high rents and of the fall in

prices in the Lowlands, and of the decline of the tacksmen in the

Highlands, of commercial distress in the cities and depression in the

small country towns. Even more important, the fact emerges that it was

in certain districts, and among certain classes and occupations, that

emigration to Australia had a particular ‘vogue’ or attraction. The

mercantile class in Edinburgh and Leith stands out among these

categories as the largest and most concentrated in location of them all.

In the four years from January 1820 no fewer than twenty-three merchants

in the capital and its port made application, and in 1824 ten more

applied—a remarkable number. By December 1824 nearly 200 applications

had been made from the district, and it was not surprising that when the

Reverend Archibald Macarthur’s ordination charge for his Van Diemen’s

Land mission was delivered in Edinburgh, extraordinary scenes should

have been witnessed at Dr. Jamieson’s chapel. According to Dr. James

Peddie, ‘hundreds were unable to gain admission’, and, even allowing

for the religious fervour of the supporters of the United Associate

Synod, the incident showed a keen public interest in this first

extension of the Scottish Presbyterian polity (albeit in secession) to

distant Australia.

Of all the intending

settlers between 1820 and 1830 whose place of origin in Scotland is

specified, 246 were in Edinburgh, Leith, the Lothians, and Fife, as

against 192 for the rest of the country. This figure, nearly

three-fifths of the total, was completely out of relative proportion to

the population of the districts specified as compared with that of the

rest of the country.

Next in importance, after

the merchants and manufacturers of Leith and Edinburgh, were the farmers

in the Lothians and Fife, of whom twenty-four applied. As well as these

two main concentrations of intending settlers, there were minor clusters

of applicants in various districts. The pressure of local distress, and

the shortage of farms and the fall in prices, were doubtless partly

responsible for this and were mentioned in some petitions, but more

often it appears that the example of some enterprising individual

inspired the emulation of friends, relations, and neighbours. An example

of this was the emigration of farmers and landowners from Caithness in

1822—3.

Among the leaders of this

movement was David Brodie, a landowner and Deputy Lieutenant whose

family had been established in that county for two centuries. In 1822 he

sold his estate and, with a capital of £3,000 applied for grants for

himself and his three sons, his referee being Alexander Macleay of the

Transport Board, another Caithness man. Brodie was possibly influenced

by the example of William and George Innes, the sons of George Innes,

tacksman of Isould, nearby, for Caithness, though not generally

considered as a Highland county, had known the tacksman system, and the

Inneses had failed to secure a renewal of the Isould lease on their

father’s death and decided to go out to Australia. By December 1823

ten applications had been made, with success, by persons in this small

area.

There were small

concentrations of applicants in other districts: three in Orkney, in

1822—3; eleven in the southern part of the county of Angus between

1820 and 1823; and from in and around the small port and market town of

Montrose, further north, there were eight applications in that period.

In 1824 seven applications came from the Highland district of Lochalsh,

in Wester Ross, five from tacksmen and two from half-pay army officers,

four of them bearing the name of Macrae and probably closely related in

blood. This group were of the tacksman class; one of them, Donald Macrae

of Achtertyre, stated that he intended to take out his servants, and

another, Duncan Macrae, stated his capital as £1,000.

Another east coast locality, adjacent to

the main emigration area of Edinburgh, Leith, the Lothians, and Fife,

and providing a number of settlers, was Dundee, from which five

applications came in 1827—8, four of the intending settlers being

merchants and the fifth a lawyer. Two of these merchants, the Bell

brothers, were connected with the Dundee firm of Bell and Balfour, which

the Scots firm of Chalmers and Guthrie in London described as ‘one of

the oldest and highest standing in point of character and wealth in the

mercantile community of Scotland’, and the Bells’ referee was given

as the Honourable Hugh Lindsay, M.P. for Dundee and chairman of the East

India Company. Their project was certainly ambitious, for the firm

planned to send out two of its ships, each ‘expedition’ to be under

one of the brothers. The capital involved was £10,000, and this venture

may have stimulated the other applications from the district.

Apart from these, there were no other

Lowland districts from which applications were made in appreciable

numbers. By the end of December 1823 only 27 applications had been

received from Glasgow and district, already the greatest centre of

population in Scotland, but by that date 84 had been received from

Edinburgh and Leith, and 46 more from the surrounding counties of the

Lothians, Fife, and Berwickshire.

Scotland was still essentially a country

of self-contained regions, and the Scottish settlers were predominantly

drawn from the south-east, with other small groups proceeding from

Caithness, Angus, the Mearns (the Montrose group), and with a number

drawn from places all over the Highlands and islands. The contribution

to the emigration of Glasgow and its surrounding industrial district,

and of the fairly thickly populated West Country of the Lowlands, was

remarkably slight.

Certain other

occupational groups figured consistently, though slightly, in comparison

with the merchants, farmers, tacksmen, and other agriculturists. There

were the half-pay army and naval officers, of whom forty-four made

application between 1817 and 1830. Roughly half of the officers who

applied were Highlanders, and many of them were tacksmen or the, sons of

tacksmen. Few, according to their accounts of their means, were wholly

dependent on their half pay, and several had farming experience. Of

those who applied from the Lowlands, a large number were resident in and

around Edinburgh, and in Fife.

A small but significant

group were the shipmasters. As early as 1801 William Stewart arrived in

Sydney as mate in a ship belonging to the Scottish firm of Campbell and

Clark of Calcutta, and soon found employment as a commander of vessels

for Commissary John Palmer, Robert Campbell, and a number of others. In

1823 no fewer than three shipmasters applied for permission to settle

and for land grants, and while the means of two of them, Andrew Donald

and John Young of Leith, were not specified, the other, William Wilson,

captained his own brig, the Deveron, and had plans to go into the

whale fishery. He also intended to take up agriculture, and had merino

sheep and farm servants ready to embark. Between 1823 and 1829 seven

more shipmasters’ applications are recorded, the last being that of

John McLeod, commander of the brig Lion, who stated his intention

of taking up agriculture on his grant in March 1829. Captain Arthur

Hogue, an applicant of 1825, master and owner of the brig Venus, which

he intended to take out, together with a capital of no less than

£25,000, had accumulated his fortune as an owner-captain in the Indian

‘Country’ trade between Bengal and Ceylon, and intended to carry on

business as a shipowner in the colony, as well as becoming an

agriculturist.

At least three of the

captains in the service of the Australian Company of Edinburgh and Leith

settled in Australia before 1830. Captains Duncan McKellar and

Christopher Moodie went out to New South Wales and took up land grants

in the late 1820s. Captain James Crear went out in the Drummore in

1830 as a settler. These cases illustrate the depression in the Scottish

shipping trade, especially in the east coast ports, following the

Peace of 1815. Even before the large-scale Scottish emigration began in

1820 several sea captains had found their way to Van Diemen’s Land,

induding Thomas Ritchie and George Frederick Read, who both went out in

1818.

Surgeons and physicians

were another prominent group. Among the Scots applicants between 1815

and 1830 there were no fewer than twenty-two surgeons and six

physicians. Some of them were extremely well qualified, like James

Murdoch, a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, ‘late

Physician Accoucheur to the Edinburgh Dispensary, and Lecturer in

Midwifery’, who advertised in Hobart in 1822 that he intended to

practise, specializing in midwifery and children’s diseases. Another

highly qualified medical man was Daniel Schaw, Fellow of the Royal

College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and an extraordinary member of the

Royal Medical Society. He, too, intended to practise in the colony, as

did Adam Turnbull, who was the son-in-law of the Postmaster-General of

Scotland and held the degree of Doctor of Medicine of Edinburgh

University.

Many had served in the

navy, and came out in charge of transported convicts. By 1820 Robert

Armstrong, David Reid, Thomas Reid, Matthew Anderson, and William

Macdonald had visited Australia twice, as surgeon-superintendents of

convict ships, and both James Bowman and Robert Espie had made three

voyages. Several of them eventually settled in the colony, including

James Mitchell, who was appointed to the Sydney Hospital in 1823 and was

later to become a coal-mining magnate, and Peter Cunningham, author of

the popular Two Years in New South Wales. A good number of Scots

surgeons in addition to these made a single voyage prior to 1820, and

among the superintendents listed by Bateson for the period up to 1832,

Scots figure to a degree out of all proportion to the relative

population of their country. In 1827 alone no fewer than five Scots

surgeons, four of them serving on convict transports and the other in

the East India Company’s marine, made application for land grants.

Other groups which

figured to a lesser extent among the applicants were the commissary

officers, of whom ten applied between 1817 and 1829, the surveyors and

engineers (6), the landowners or sons of landowners (32), the distillers

or brewers (5), teachers (5), retired East India officers (6),

shipbuilders (3), mechanics (11), and manufacturers of cottons, woollens,

silks, to the number of eight. Yet, with the exception of the army

officers, these categories were small in comparison with the merchants

(83) and the farmers (97) who applied in the same period. Still, the

smaller professional groups of lawyers, surgeons, physicians, and

teachers included many most useful additions to the colonial population.

The lawyers included young men like

Alexander McPhail, who had only recently completed his training as a

solicitor (but who would be ‘under the protection of Governor

Macquarie’),’ and George Miller, a young writer who had served his

legal apprenticeship with the town clerk of Perth. Others were

experienced lawyers, like David Taylor, son of an Edinburgh official,

who asked not only for a grant but for the registrarship of the colony,

enclosing with his application a letter he had received from Colonel

George Johnston of Annandale, Sydney (a friend of his father). Johnston

described the improvements in the colony and wrote of the ‘number of

respectable gentlemen recently arrived from Scotland as settlers’.

Despite the differences between English law and the Scots law to which

they had been accustomed, the lawyers took up practice in Australia, and

some, like Robert Pitcairn, who became solicitor to the Australian

Company in Hobart, came to be regarded as among the leading lawyers of

the colony.

The teachers included both experienced

men like James Ross, who had conducted his own school in London, and

William Thomson of Edinburgh, ‘teacher of drawing and painting’, and

inexperienced young men like the son of the minister of Dunbog in Fife,

himself a licensed clergyman with a university education, who hoped to

establish his own school in Van Diemen’s Land. Archibald Macarthur,

the first Presbyterian clergyman to go out, in 1822, also planned to

establish a school, and took with him a library and a printing-press.

James Sprent of Glasgow, a graduate of the University there, was yet

another who established a school—an academy for boys in Hobart, which

flourished from 1831 until Sprent was engaged by the Government to

conduct the trigonometrical survey of the island. Eventually he became

surveyor-General.

The surveyors and

engineers were another of the small, but important, professional groups.

Among them was John Busby of Edinburgh, a civil engineer who had taken

part in many of the important public works of the time, including the

Caledonian Canal, the Loch Ryan harbour, and the military works at

Stirling Castle. In Australia he was to achieve local fame by the

planning and construction of ‘Busby’s Bore’, a piped water supply

for Sydney. Another was Peter Fleming of Glasgow, who had

experience of planning roads and waterworks in Scotland and had worked

under Thomas Telford, to whom he referred the authorities in support of

his application. Alexander Kinghorn of Roxburgh, who applied in 1823,

had also taken part in the great Scottish road improvements of the time,

and was recommended to Bathurst by Sir Walter Scott. Another was John

Dickson, engineer, who took out the colony’s first steam engine in

1813.

The printing, publishing,

and ancillary trades were also well represented among the Scottish

emigrants. In Sydney in the late 1820s, nearly all of the fine engraving

work for the local presses was done by John Carmichael, James and

William Wilson, and William Moffitt, and in Hobart Scots were to the

fore in the new field of journalism. By 1827 Henry Melville was editing

the Colonial Times in that town and directing a steady flow of

candid criticism against the Van Diemen’s Land authorities, while his

fellow countryman John C. McDougall was editing the rival Tasmanian. In

the same small capital yet another Scot, the Edinburgh lawyer Dr. James

Ross, was editing two more newspapers, the official Hobart Town

Gazette and his own private venture, the Hobart

Town Courier.

...continue

to Part 3

|