|

'IN the history of the next five years' after the

battle of Falkirk, writes Lingard, Wallace's 'name is scarcely ever

mentioned.' The suggestion seems to be that Wallace ceased to be an

influential factor in the course of events. But after all Lingard is driven

to acknowledge the force of Wallace's personality, at the expense of his own

consistency. He comes to admit that 'the only man whose enmity could give'

Edward a 'moment's uneasiness, was Wallace.' The statement looks remarkably

like a reproduction Of an English scribe's assertion that, after the

submission of Comyn and the other nobles, there was left but 'one disorderly

fellow (unus ribaldus), William Wallace by name, who gave the King just a

touch of uneasiness' Edward

himself, it is plain, had formed a" very different estimate of that touch.

He was well aware that the other Scots leaders would stand with him or

against him according to the strength of his grip on the country; more than

once he had beheld both sides of the political coats of most of them. The

more dangerous of them—three or four—he could muzzle effectivelyenough by a

short period of banishment, during which he would reduce the inflammability

of the materials they could work upon. Wallace, however, was a conspicuously

abler man than any of the time-servers; he was the one prominent Scot that

had never submitted; and he was known to be resolutely irreconcilable. There

remained only one course: Wallace must be destroyed.

Edward, with the siege of Stirling before him, would

not have been likely to allow resentment to overbear policy in the case of

any of the Scots leaders, unless he had become convinced that the particular

offender was either not worth consideration or else hopelessly recalcitrant.

There must, indeed, as Lingard says, have been 'something peculiar' in

Wallace's case, 'which rendered him less deserving of mercy' than the

others. Wallace alone was expressly excluded from the treaty of Strathord.

Sir John Comyn, the head and front of the immediate offending, escaped

easily by the ignominious door of abject humiliation. The Steward and Sir

John de Soulis, who had on previous occasions bent to like necessities, were

let off with two years' banishment south of Trent. Sir Simon Fraser and

Thomas du Bois— both men that compelled the respect of their opponents —were

more severely dealt with, by exile for three years from Scotland, England,

and France. Yet Edward must have had very distinctly in his mind the

mortifying defeat of Roslin, achieved by Comyn and Fraser. The chameleon

Bishop of Glasgow, 'for the great harm he has done,' was merely banished for

two or three years. In any case, these judgments were but slackly enforced,

even in those instances where enforcement was within Edward's power. But

Wallace—'he may come in to the King's grace, if he thinks good.' It is idle

to speculate what Edward would have done with him if he had then 'come into

the King's grace.'

Edward had

certainly made attempts to conciliate Wallace. By the agency of Warenne, he

did so just before the battle of Stirling. He may even have offered the

patriot his royal pardon, with lordships and lands. Bower says he did. He

may, though not at all probably, have dangled before him the crown of

Scotland under English suzerainty. The record of the judgment pronounced on

Wallace mentions that after Falkirk the King had 'mercifully caused him to

be recalled to his peace'; and the reference is probably to some specific

overture, and not merely to the general summons. Bower reproduces the story

that Wallace's friends now urged his acceptance of the proposed terms, and

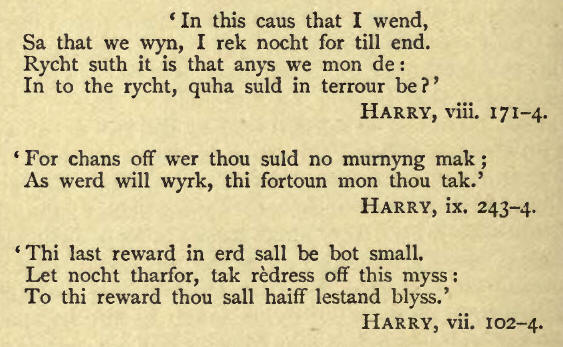

that Wallace thereupon delivered his sentiments as follows:-

'O desolate Scotland, over-credulous of deceptive

speeches, and little foreseeing the calamities that are coming upon you! If

you were to judge as I do, you would not readily place your neck under a

foreign yoke. When I was a youth, I learned from my uncle, a priest, this

proverb—a proverb worth more than all the riches of the world—and ever since

I have marked it in my mind

And therefore, in a word, I declare that, if all

Scotsmen together yield obedience to the King of England, or part each one

with his own liberty, yet I and my comrades who may be willing to adhere to

me in this behalf, will stand for the freedom of the realm ; and, with God's

help, we will obey no man but the King, or his lieutenant.'

Whether this striking scene was ever enacted or not,

there can be no doubt that the writer represents with - fidelity the

attitude of Wallace.- The rejection of the King's proffered clemency, even

if but indirectly or generally proffered, would naturally sting his proudly

sensitive feeling. In any case, Edward was fully satisfied that he would

never have peace in Scotland while Wallace was in the field, and that

Wallace would contemn alike his threats and his promises, and succumb only

to superior force or to insidious policy.

Early in 1303-4, Edward had made up his mind that he

would receive Wallace on no terms short of unconditional surrender, and he

was determined to have him in his power at the earliest possible moment. To

somewhere very near this period—say February—must probably be assigned an

undated draft of letters-patent, whereby Edward grants to his 'chier vadlet'

(dear vallet), Edward de Keith, afterwards Sheriff of Selkirk, all goods and

chattels of whatever kind he may gain from Sir William Wallace, the King's

enemy, to his own profit and pleasure. At this date, certainly, Edward was

putting all irons in the fire to accomplish his intense wish to lay hands

upon the redoubtable Wallace.

About this time Wallace and his followers appear to

have been hovering not very far away, south of Forth. Sir Alexander de

Abernethy, Warden between the Mounth and the Forth, had been despatched by

the Prince of Wales to Strathearn, Menteith, and Drip, to guard the passage

of the river. Sir Alexander appears to have written to the King on the

subject of terms to Wallace. In his answer, dated March 3, Edward laid down

definitively, once more, the requirement of unconditional submission:-

' In reply to your request for instructions as to

whether it is our pleasure that you should hold out to William Wallace any

words of peace, know that it is not at all our pleasure that you hold out

any word of peace to him, or to any other of his company, unless they place

themselves absolutely (de haut ci de bas) and in all things at our will

without any reservation whatsoever.'

The final corrections of the original draft of this

letter indicate how careful Edward was to express his stern resolution with

unmistakable precision and emphasis. Wallace must surrender at discretion.

There is nothing to show whether Sir Alexander

Abernethy had put the point to Edward of his own motion, in view of

contingencies, or on the prompting of some application addressed to him from

the Scots side. It seems more likely that he was hopeful of success, and

wished to fortify himself with definite instructions. The first paragraph of

the letter shows markedly the King's sense of the importance of Sir

Alexander's service: he urges the knight to all possible diligence; he

signifies where aid, if necessary, may be had; and he orders that Sir

Alexander shall not leave his service in these parts unaccomplished,

'neither for the parliament nor for any other business.' The same day (March

3), Edward wrote to 'his loyal and faithful Robert de Brus,' applauding his

diligence on that side the Forth, and urging him, 'as the robe is well made,

you will be pleased to make the hood.' Two days later he directed the Prince

of Wales to reinforce Abernethy at the fords and passes above Drip; and on

March i i he sent special instructions also to the Earl of Strathearn to see

to the guarding of the fords and of the country about, so that none of the

enemy might cross to injure the King's lieges on the north side. The

proximity of Wallace, and the hope of putting him down finally, no doubt had

a foremost place in Edward's calculations. It does not seem likely, though

it may have been the case, that application had been made to Abernethy on

behalf of Wallace; perhaps the King's reply would have specifically

indicated the fact. It is not to be believed for an instant that any such

application would have been made with the sanction or knowledge of Wallace

himself.

But for the absurd

bias of Langtoft, one might be inclined to connect an episode of his with

the negotiations that issued in the treaty of Strathord and with Sir

Alexander de Abernethy's letter. After Christmas 1303, Langtoft says,

Wallace lay in the forest—the glen of Pittencrieff has been suggested as the

particular spot— and 'through friends' made request to the King at

Dunfermline 'that he may submit to his honest peace without surrendering

into his hands body or head, but that the King grant him, of his gift, not

as a loan, an honourable allowance of woods and cattle, and by his writing

the seisin and investment for him and his heirs in purchased land.' The

whole bent of Wallace's mind was undoubtedly against any such application.

Anyhow, 'the King,' says Langtoft, 'angered at this demand, breaks into a

rage, commends Wallace to the devil, and all that grows on him, and promises

300 marks to the man that shall make him headless.' Whereupon Wallace takes

to the moors and the hills and 'robs for a living.'

Wallace, however, had very different business on hand.

Apparently he had found it hopeless to effect the passage of the Forth or to

communicate with Stirling Castle; Sir John de Segrave, the Warden south of

Forth, had joined hands with Bruce and Clifford to attack him. He had

therefore retired into Lothian, Sir Simon Fraser with him, and the English

force in pursuit. A renegade Scot, John de Musselburgh—let his name be

pilloried!— guided the English commander to the retreat of his countrymen.

Wallace and Fraser were brought to bay at Peebles (Hopperewe) in Tweeddale,

and defeated. The news was brought to Edward at Aberdour on March 12; and on

March 15, John of Musselburgh received from the gratified King's own hand

the noble guerdon of 10s.

Already Edward was deep in preparations for the siege of Stirling, which, as

we have seen, absorbed his whole energies from the middle of March till late

in July. On July 25, 1304, the day after the formal surrender of the

obstinate castle, he was in high good humour. There has been preserved the

roll of magnates and others that served under him in this campaign; and one

of the paragraphs informs us how the King on that day commanded fourteen

barons therein named to settle in what manner they and the others on the

roll should be rewarded for the services they had rendered. At the same time

his mind recurred with renewed energy to Sir William Wallace. A later

paragraph represents him as attempting to enlist the Scots leaders whose

terms of submission had been arranged in the beginning of February, in a

comprehensive hunt after Wallace. There is no crude mention of a specific

blood-price in marks. But on the success of the hunt their own future

treatment is made very expressly dependent. Comyn, Lindsay, Graham, and

Fraser, who had been adjudged to go into exile, as well as other Sects

liegemen of Edward, were enjoined to do their endeavour 'between now and the

twentieth day after Christmas' to capture Wallace and to render him to the

King. The King will see how they bear themselves in the business, and will

show more favour to the man that shall have captured Wallace, by shortening

his term of exile, by diminishing the amount of his ransom or of his

obligation for trespasses, or by otherwise lightening his liabilities. It is

further ordained that the Steward, Sir John de Soulis, and Sir Ingram de

Umfraville shall not have any letters of safe- conduct to come into the

power of the King until Sir William Wallace shall have been surrendered to

him. It stands to the eternal credit of the comrades of Wallace that they do

not appear—not one of them—to have taken a single step to better or shield

themselves by ignominious treachery to their undaunted friend.

Apparently Wallace and Fraser had got together some

followers again, after their defeat at Peebles, and had drawn towards

Stirling in the hope of effecting some diversion in favour of the gallant

garrison. They do not, however, seem to have been strong enough to

contribute any useful support. After the capitulation of Stirling Castle, an

English force appears to have proceeded against them, for in September there

is record of a pursuit after Wallace 'under Earnside.' But there are no

particulars available: the record affords but a momentary glimpse into the

darkness.

Meantime the

attempt to capture Wallace was steadily kept up by Edward and his

emissaries. On February 28, 1304-5, Ralph de Haliburton, who was—unhappily

for his honour—one of the Scots survivors of the siege of Stirling Castle,

was released from prison in England, and delivered to Sir John de Mowbray,

'of Scotland, knight,' to be taken to Scotland 'to help those Scots that

were seeking to capture Sir William Wallace.' It stands on record that Sir

John and others gave security to re-enter Ralph at the parliament in London

in three weeks from Easter (April iS), 'after seeing what he can do.' But,

so far as appears, the miserable renegade was not able to do anything

effective. Is this possibly 'Ralph Raa'?

Somewhere about this period may probably be placed an

episode in the chequered career of a Scots squire, Michael de Miggel, who

had been in Wallace's hands, if not actually of his company. Michael had

done homage to Edward in the crowd on March 14, 1295-96, but had promptly

repented, for in six weeks' time he was taken prisoner in Dunbar Castle. For

eighteen months thereafter he was confined in the Castle of Nottingham;

which may probably indicate that the English officers were aware that he

needed to be strictly looked after, On September 1, 1305, an inquisition was

held at Perth 'on certain articles touching the person of Michael de Miggel,'

the substantial charge apparently being that he had been a confederate of

Wallace. The sworn statement of the inquisitors was 'that he had been lately

taken prisoner forcibly against his will by 'William le WTaleys; that he

escaped once from William for two leagues, but was followed and brought back

by some armed accomplices of William's, who was firmly resolved to kill him

for his flight; that he escaped another time from said William for three

leagues or more, and was again brought back a prisoner by force with the

greatest violence, and hardly avoided death at William's hands, had not some

accomplices of William's entreated for him; whereon he was told if he tried

to get away a third time he should lose his life. Thus it appears,' they

concluded, 'he remained with William through fear of death, and not of his

own will.' The explanation served. The date 'lately' in all probability

places the episode in the last few months of Wallace's career. It at least

confirms the strenuous persistence of Wallace, as far as his means would

permit, against the enemies of his country, and their relentless hunting

down of all his adherents.

Unable to maintain himself in the east, Wallace retired to the west. Whether

Harry be right or wrong in making Sir Aymer de Valence bargain with Sir John

de Menteith for the capture of the patriot, matters little; the result is

the same. Menteith, in any case, took up the hunt. It has been somewhat

strangely urged in palliation of his infamy, that he was then Edward's man.

True, he was Edward's man; and since March 20, 1303-4, he had been Constable

of Dumbarton Castle and town, and Sheriff of Dumbartonshire. He was

therefore acting in the plain way of duty. At the same time, the previous

question remains to be disposed of: why was he, a Scots knight, the man of

the English King? Instead of palliating his infamy, his official position

only deepens its blackness. The despised Harry finds a much more plausible

excuse for the poor-spirited creature. Harry depicts him as displaying

reluctance; as urging to Sir Aymer-

'He is our governor; For us he stood in many a felon

stour, Not for himself, but for our heritage: To sell him thus it were a

foul outrage.'

Harry appears

to think that Menteith was Constable of Dumbarton in Wallace's interest; and

the dramatic remonstrance he puts into Menteith's mouth is sufficiently

transparent. However, it elicits from Sir Aymer a promise that Wallace's

life shall be safe, and that Edward will be satisfied if his great enemy be

securely lodged in prison. On this promise, Menteith consents. True or

untrue, it is the only decent plea that has ever been suggested on

Menteith's behalf; and even then it disgraces his intelligence. Harry

further indicates that Menteith, after all, delayed somewhat in the

execution of the project. He says that Edward wrote to Menteith privately,

and 'prayed him to haste.' The infamous wretch sorely needs the full benefit

of Harry's palliations.

Menteith proceeded to carry out his scheme. Harry says he got 'his sister's

son' to attach himself to Wallace's personal following, with full

instructions for the betrayal. The youth was to inform Menteith of Wallace's

movements, so as to enable him to effect the capture under the most

favourable conditions. This subordinate tool is said to have been named Jack

Short: the authority of Langtoft is usually given, but mistakenly; it is not

Langtoft, but Langtoft 'illustrated and improved' by Robert of Brunne, that

mentions 'Jack Short his man' as the instrument of Wallace's betrayal,

adding by way of explanation, that 'Jack's brother had he slain.'

The desired opportunity soon offered. According to

Harry, Bruce, in reply to an invitation to come and claim the crown,

informed Wallace that he would devise an excuse for leaving the English

court, and endeavour to meet him on Glasgow Moor on the first night of July.

Attended only by the ever - faithful Kerly and the treacherous emissary of

Menteith, Wallace rode out on several evenings from Glasgow to Robroyston,

in expectation of Bruce. On 'the eighth night,' Menteith received notice,

and with sixty sworn men—'of his own kin, and of kinsmen born'—he hurried to

the scene. About midnight, Wallace and Kerly went to sleep - a very unlikely

thing for Kerly to do in the circumstances. The traitorous attendant then is

said to have removed their arms, and given the signal to Menteith. Kerly was

instantly despatched. Wallace started up, and, missing his arms, defended

himself with his hands. Menteith then came forward, and represented that

resistance was in vain, the house being surrounded by English troops; that

the English really did not wish to kill him; and that he would be safe under

his protection in his (Wallace's) own house in Dumbarton Castle. Wallace

thought that Menteith, his gossip—nay, 'his gossip twice' (for Major, in

consonance with Harry, records that Wallace had stood godfather to two of

Menteith's children)—might be trusted; still he made him swear. As Harry

remarks, 'That wanted wit; what should his oaths avail any more, seeing he

had been long forsworn to him?' The oath taken, Wallace resigned his hands

to the 'sure cords' of Menteith.

As they fared forth, Wallace saw no Southrons, and he

missed Kerly—to him convincing signs of betrayal. Still Menteith protested

that the sole intention was to keep their prisoner in security; there was no

design against his life. The truth, however, was at once evident. Menteith

did not proceed to Dumbarton, but took his way right south with all speed,

'aye holding the waste land,' for 'the traitors durst not pass where

Scotsmen were masters,' and it was essential to their purpose to gain time

on Wallace's men, and to baffle the certain pursuit. On the south side of 'Solway

sands,' Menteith delivered Wallace to Sir Aymer de Valence and Sir Robert de

Clifford, who conducted him 'full fast' to Carlisle, where they threw him

into prison. His real custodian, however, appears to have been Sir John de

Segrave, the Warden south of Forth.

Such writers as exculpate Menteith from participation

in the capture of Wallace lie under the obligation of explaining the

following facts. There still exists a document that looks like a memorandum

of business for Edward's parliament or council. It notes that 40 marks are

to be given to the vallet who spied out (espia) William Wallace; that 6o

marks are to be given to the others, and that the King desires they shall

divide the money among them; and that £ioo in land is to be given to John de

Menteith. Again: shortly after the middle of September, when the Scots

commissioners attended the English parliament for the special purpose of

agreeing to regulations for the settlement of Scotland, nine, instead of

ten, appeared; and in place of Earl Patrick, who was the absent member, Sir

John de Menteith 'by the King's command was chosen.' By one of the

regulations then agreed to, Sir John de Menteith was confirmed in the

governorship of Dumbarton Castle. Further: on November 20, 1305, a signal

mark of royal favour is recorded with peculiar emphasis. At the request of

'his faithful and loyal John de Menteith,' Edward commands his Chancellor to

issue letters of protection and safe-conduct in favour of certain burgesses

of St. Omer passing with their goods and merchandise through his dominions;

the letters to be framed in such especial form as John de Menteith shall

wish 'in reason,' to last for two or three years as pleases him most. The

Chancellor is to deliver them without delay to Menteith, and to no other;

for the King has granted them to him 'with much regret,' and would have

given them to no other than himself. And finally, on June 16, 1306, Edward

commands Sir Aymer de Valence to deliver to Sir John de Menteith the

temporality of the bishopric of Glasgow towards Dumbarton, during pleasure;

and on the same date he informs Sir Aymer that he has ordered the Chancellor

and Chamberlain to prepare a charter granting the Earldom of the Lennox to

Sir John de Menteith, 'as one to whom he is much beholden for his good

service, as Sir Aymer tells him, and he hears from others,' and he commands

Sir Aymer to give him seisin. Harry may have mixed up the facts a little,

but it is plain that he has got hold of the main thread. Apart from the

capture of Wallace, it is simply incredible that Menteith's services would

have been deemed so markedly valuable in the eyes of the English King.

Having apprised Edward of the capture of his great

enemy, Valence and Clifford brought Wallace on to London. Harry says Valence

and Clifford, but no doubt he ought to have said Sir John de Segrave; at any

rate, Wallace was in the custody of Segrave on August 18. The news of

Wallace's coming had spread far and wide, and as the cavalcade approached

the capital, it was met by a multitude of men and women, curious to gaze

upon the rebellious savage—says Stow, 'wondering upon him.' The illustrious

captive was lodged in the house of Alderman William de Leyre, in the parish

of Allhallows Staining, at the end of Fenchurch Street. It may seem strange

that he was not taken to the Tower. In any case, it is in the last degree

improbable that the fact points to any intention of Edward to make a final

attempt to secure Wallace's submission to his grace. There is certainly more

probability in Carrick's conjecture, that the reason was 'the difficulty

which the party encountered in making their way through the dense multitudes

who blocked up the streets and lanes leading to the Tower.' Anyhow, it is a

point of very subordinate interest. The date of the arrival was Sunday,

August 22.

No time was lost.

Everything was in readiness. The very next morning, Monday, August 23, 1305,

Wallace was conducted on horseback from the City to Westminster, to undergo

the farce of trial. Sir John de Segrave was in command of the escort, and

with him there rode the Mayor, Sheriffs, and Aldermen of London, followed by

a great number of people, on horseback and on foot. Arrived at Westminster

Hall, Wallace was placed on the bench on the south side. It is said that, as

he sat there awaiting his doom, he was crowned with a garland of laurel

leaves. The popular English fancy absurdly associated this strange procedure

with an alleged assertion of Wallace's in times past, to the effect that he

deserved to wear a crown in that Hall. Some writers regard it as a mark of

derision. Llewelyn's head had been exposed on the battlements of the Tower

crowned with a wreath of ivy—said to be in fulfilment of a prophecy of

Merlin's. Sir Simon Fraser is said, in the ballad, to have been drawn

through the streets to the gallows with 'a garland on his head after the new

guise'; though Langtoft says Fraser's head was fixed on London Bridge

'without chaplet of flowers,' as if the omission were a noticeable breach of

custom. It is a mistake, then, to suppose that the garland was a special

insult to Wallace. It may have marked the satisfaction of victory over a

notable enemy. It may be taken as the fillet of the destined victim.

The Commissioners appointed to try Wallace were Sir

John de Segrave; Sir Peter Malory, the Lord Chief Justice; Ralph de

Sandwich, the Constable of the Tower; John de Bacwell (or Banquelle), a

judge; and Sir John le Blound (Blunt), Mayor of London. They had been

appointed by Edward on August 18. They were all present. The indictment was

comprehensive, charging sedition, homicide, spoliation and robbery, arson,

and various other felonies. The charge of sedition or treason was based on

Edward's conquest of Scotland. On Balliol's forfeiture, he had reduced all

the Scots to his lordship and royal power; had publicly received homage and

fealty from the prelates, earls, barons, and a multitude of others; had

proclaimed his peace throughout Scotland; and had appointed wardens, his

lieutenants, sheriffs, and others, officers and men, to maintain his peace

and to do justice. Yet this Wallace, forgetful of his fealty and allegiance,

had risen against his lord; had banded together a great number of felons,

and feloniously attacked the King's wardens and men; had, in particular,

attacked, wounded, and slain William de Hazeirig, Sheriff of Lanark, and, in

contempt of the King, had cut the said Sheriff's body in pieces; had

assailed towns, cities, and castles of Scotland; had made his writs run

throughout the land as if he were Lord Superior of that realm; and, having

driven out of Scotland all the wardens and servants of the Lord King, had

set up and held parliaments and councils of his own. More than that, he had

counselled the prelates, earls, and barons, his adherents, to submit

themselves to the fealty and lordship of the King of France, and to aid that

sovereign to destroy the realm of England. Further, he had invaded the realm

of England, entering the counties of Northumberland, Cumberland, and

Westmoreland, and committing horrible enormities. He had feloniously slain

all he had found in these places, liegemen of the King; he had not spared

any person that spoke the English tongue, but put to death, with all the

seventies he could devise, all—old men and young, wives and widows, children

and sucklings. lie had slain the priests and the nuns, and burned down the

churches, 'together with the bodies of the saints and other relics of them

therein placed in honour.' In such ways, day by day and hour by hour, he had

seditiously and feloniously persevered, to the danger alike of the life and

the crown of the Lord King. For all that, when the Lord King invaded

Scotland with his great army and defeated William, who opposed him in a

pitched battle, and others his enemies, and granted his firm peace to all of

that land, he had mercifully had the said William Wallace recalled to his

peace. Yet William, persevering seditiously and feloniously in his

wickedness, had rejected his overtures with indignant scorn, and refused to

submit himself to the King's peace. Therefore, in the court of the Lord

King, he had been publicly outlawed, according to the laws and customs of

England and Scotland, as a misleader of the lieges, a robber, and a felon.

It was laid down as not consonant with the laws of

England, that a man so placed beyond the pale of the laws, and not

afterwards restored to the King's peace, should be admitted either to defend

himself or to plead. Still it is recorded that Wallace, whether regularly or

irregularly, did reply to Sir Peter Malory, denying that he had ever been a

traitor to the English King. He is also said to have acknowledged the other

charges preferred. There are allegations of wanton and extravagant misdeeds

that undoubtedly merited denial, and could not have been positively

acknowledged by Wallace. It may be that he considered it futile to raise any

further objection, and heard the charges with the contempt of silent

indifference.

Sentence was

pronounced:

'That the said

William, for the manifest sedition that he practised against the Lord King

himself, by feloniously contriving and acting with a view to his death and

to the abasement and subversion of his crown and royal dignity, by opposing

his liege lord in war to the death, be drawn from the Palace of Westminster

to the Tower of London, and from the Tower to Aldgate, and so through the

midst of the City, to the Elms.

'And that for the robberies, homicides, and felonies

he committed in the realm of England and in the land of Scotland, he be

there hanged, and afterwards taken down from the gallows;

'And that, inasmuch as he was an outlaw, and was not

afterwards restored to the peace of the Lord King, lie be decollated and

decapitated;

'And that

thereafter, for the measureless turpitude of his deeds towards God and Holy

Church in burning down churches, with the vessels and litters wherein and

whereon the body of Christ and the bodies of saints and relics of these were

placed, the heart, the liver, the lungs, and all the internal organs of

William's body, whence such perverted thoughts proceeded, be cast into fire

and burnt;

'And further, that

inasmuch as it was not only against the Lord King himself, but against the

whole Community of England and of Scotland, that he committed the aforesaid

acts of sedition, spoliation, arson, and homicide, the body of the said

William be cut up and divided into four parts; and that the head, so cut

off, be set up on London Bridge, in the sight of such as pass by, whether by

land or by water; and that one quarter be hung on a gibbet at

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, another quarter at Berwick, a third quarter at Stirling,

and the fourth at St. Johnston, as a warning and a deterrent to all that

pass by and behold them.'

In

execution of this atrocious sentence, Wallace was dragged at the tails of

horses through the streets of London to the Elms in Smithfield (i.e.

Smoothfieldlater Cow Lane, now King Street). At the foot of the gallows, he

is said to have asked for a priest, in order to make confession. Harry seems

confused in placing this incident before the procession to Westminster and

his representation of the Archbishop of Canterbury as shriving Wallace, in

defiance of Edward's express general prohibition, is at any rate highly

coloured in the details. Harry further records that Wallace requested

Clifford to let him have the Psalter that he habitually carried with him;

and that, when this was brought, Wallace got a priest to hold it open before

him 'till they to him had done all that they would.' The sentence was

faithfully carried out through all its stages. The English chroniclers gloat

over the inhuman savagery, some of them describing details of dishour to the

heroic victims's body such as may find no place on this page. The head was

fixed

formality of trial was a mere abuse of judicial

process, calculated to befool people already disposed to be befooled. Once

more Edward took care to shelter himself under the forms of legal procedure.

The elaborate series of. niheiits..assigned to the

various categories of Wallaces's alledged misdeeds illustrates forcibly the

base vindicitudes of Edward. A soldier like him might have been expected to

show soldierly appreciation of the most gallant enemy he ever faced. The

zeal manifested in vengeance for the alleged dishonour to God and the holy

saints is sufficiently edifying, even for the early years of the fourteenth

century. It cloaks the malignant gratification of personal malice with the

dazzling profession of the championship of religion. When the spacious Abbey

of Dunfermline was burnt to the ground only eighteen months before, that was

presumably not for the dishonour, but for the glory, of God and the holy

saints. The point of view is notoriously important.

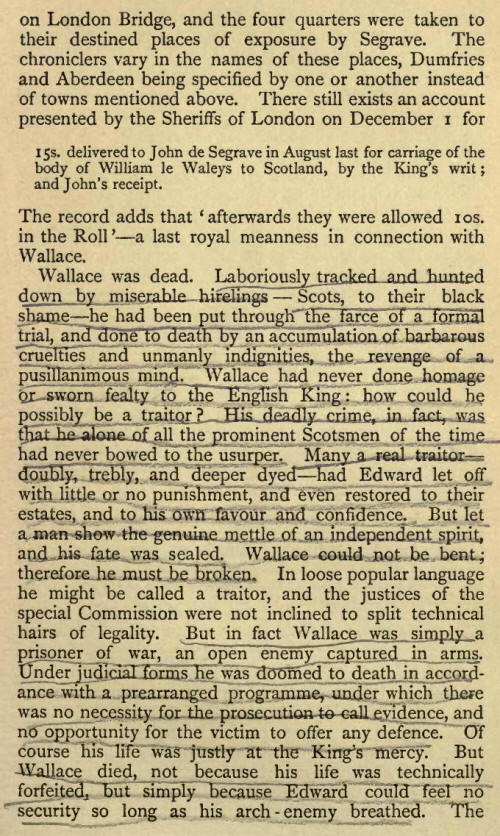

Wallace was dead. His body was dismembered, and

distributed in the great centres of his activity and influence, as an

encouragement to English sympathisers, and a sign of retribution to Scots

that might yet cherish. the foolishness of patriotism. The moral has been

well rendered by Burton

'The

death of Wallace stands forth among the violent ends which have had a

memorable place in history. Proverbially such acts belong to a policy that

outwits itself. But the retribution has seldom come so quickly, and so

utterly in defiance of all human preparation and calculation, as here. Of

the bloody trophies sent to frighten a broken people into abject subjection,

the bones had not yet been bared ere they became tokens to deepen the wrath

and strengthen the courage of a people arising to try the strength of the

bands by which they were bound, and, if possible, break them once and for

ever.'

Wallace had done his

work right well and truly, as builder of the foundations of Scottish

independence. He had sealed his faith with his blood. Probably he died

despairing of his country. Yet barely had six months come and gone when his

dearest wish was fulfilled. The banner of Freedom waved defiance from the

towers of Lochmaben, and in the Chapel-Royal of Scone the Bruce was crowned

King of Scotland.

|