THE clannishness of Scotsmen has become proverbial

all over the world, and is more frequently alluded to by "foreigners"

with a sneer than with any degree of encomium. Other nationalities,

except in one respect, are quite as clannish as the Scots, and it is

therefore difficult to understand why this quality in our countrymen

should be ridiculed and talked about as though it were something which

other people should not imitate. The clannishness of the Scot has

nothing in its make up. which is not found commendable in family life.

Besides, it is an expensive characteristic at times. It costs money. It

makes the canny Scot put his hand in his pouch now and again, an act

which his enemies or traducers do not give him much credit for, and in

thus backing up his nationality with his bawbees, the Scot's

clannishness is different from that of anyone else. In the United

States, for instance, as far as my observation has gone, the Scot spends

in charity among his ain folk ten times as much as the Englishman,

twenty times as much as the wanderer from ''Vaterland," and fifty times

as much as any other nationality which might be named. Of course, the

Scotsman is hard and careful in money matters. When he gets a dollar he

looks at both sides of it, and he holds a penny in his hand very closely

until the moment comes that he has to spend it. But when a tale of

distress is poured into his ear, when the widow and orphan appeal to his

aid, when his judgement is sure that by undoing the tight band around

his purse-strings he can alleviate misery or help the poor to rise in

the world, no man is more willing or more generous. This is equally a

characteristic of the Scot at home. In the grand old city of Edinburgh

may be found charitable and educational institutions of which any nation

might be proud, homes for the sick, the blind, the infirm, the aged, the

orphan, or the widow, established and endowed by kindly Scots, and

maintained without national or municipal aid. The practical nature of

the people is illustrated by the educational facilities which Scottish

benefactors have placed within the reach of the poor, and, long before

school boards came into existence, thousands of Edinburgh children were

thoroughly educated in such institutions as Heriot's, Stewarts or

Watson's hospitals, and the free Heriot schools.

But in dealing with

clannishness and its results we come mainly in contact with the Scot

Abroad. So far as I can learn, the common talk of the national

clannishness originated several centuries ago on the continent of

Europe. A large number of Scots fought in Sweden and Germany— soldiers

of fortune like Dugald Dalgetty—but still men with warm hearts and

kindly sentiments who ever maintained a regard for their motherland

amidst all the smiles or frowns which the fortunes of the wars brought

them. The long friendship which existed between Scotland and France,

made the latter country quite a favorite with the warlike Caledonians,

especially in those rare intervals when peace reigned on the north side

of the Tweed. The Scots Guards in France by its loyalty to the cause it

adopted, its proved reliability for all sorts of service which the

exigencies of the State demanded, as well as by its valor, rose to be

a power in the land to which it gave its services, and its record as it

has come down to us is not equaled in its tales of perilous adventures,

reckless bravery, determined resistance and deeds of gallantry by that

of any other body of men in either ancient or modern times.

The Scots

Guards appear to have been first organized by King Charles VII. They

were the most trusted of all the royal troops and the royal person was

virtually placed in their care. An old record tells us that "two of

them assisted at mass, vespers, and ordinary meals, on high holidays at

the ceremony of the royal touch, and the erection of the knights of the

king's order at the reception of extraordinary ambassadors, and public

entries of cities there must be six of their number next to the king's

person, three on each side of his majesty and the body of the king must

be carried by these only, wheresoever ceremony requires, and his effigy

must be attended by them. They have the keeping of the key of the king's

lodging at night, the keeping of the choir of the church, the keeping

the boats when the king passes the river, the honor of bearing the white

silk fringe in their arms which is the coronal color in France, the keys

of all the cities where the king makes his entry given to their captain

in waiting or out of waiting." In 1547 Henry II. granted letters of

naturalization to the Scots Guards, and Henry IV. not only confirmed

this privilege but extended it to all Scots then residing in France, or

who might afterwards take up their residence there. Thus the Guards not

only received benefits for themselves but their fame caused a share, at

least, of their privileges to become the common property of their

countrymen. Sir Walter Scott, in his novel of ''Quentin Durward," gives

us a capital idea of the consequence in which these Guards were held and

of the life they led at court and in the field. Here is a description of

the equipment of one of the troopers, the maternal uncle of the hero of

the story. "He wore his national bonnet, crested with a tuft of

feathers, and with a Virgin Mary of massive silver for a brooch. The

archer's gorget, arm pieces and gauntlets were of the finest steel,

curiously inlaid with silver, and his hauberk or shirt of mail was as

clear and bright as the frostwork of a winter morning upon fern or

briar. He wore a loose surcoat or cassock of rich blue velvet, open at

the sides like those of a herald, with a large white St. Andrew's cross

of embroidered silver bisecting it both before and behind—his knees

and legs were protected by hose of mail and shoes of steel. A broad

strong poniard (called the Mercy of God), hung by his right side, the

baldric for his two-handed sword, richly embroidered, hung upon his left

shoulder, but for convenience he at present carried in his hand that

unwieldy weapon which the rules of his service forbade him to lay

aside." This important looking personage was a gentleman by birth and

station, a fact which neither he nor any of his comrades were ever

likely to forget. Here is Sir Walter Scott's graphic description of the splendors of the Guards; "The French monarchs made it their policy to

conciliate the affections of this select band of foreigners by allowing

them honorary privileges and ample pay, which last most of them disposed

of with military profusion in supporting their supposed rank. Each of

them ranked as a gentleman in place and honor, and their near approach

to the king's person gave them dignity in their own eyes as well as

importance in those of the nation of France. They were sumptuously

armed, equipped and mounted ; and each was entitled to allowance for a

squire, a valet, a page and two yeomen. * * * With these followers and a

corresponding equipage, all of the Scottish Guards was a person of

quality and importance, and vacancies being generally filled up by those

who had been trained in the service as pages or valets. The cadets of

the best Scottish families were often sent to serve under some friend or

relation in those capacities until a chance of preferment should occur."

In 1419 the Earl of Buchan landed at Rochelle with a force variously

computed at 7,000 to 10,000 Scottish troops. Though the Scots were

looked upon at first with suspicion as "sacs a yin et inangeurs du

mouton," their valor at the battle of Bauge, in 1421, won the first

success for Charles VII. The following particulars regarding the

exploits of the Scots Guards at Bornge are gleaned from the Rev. W.

Forbes Leith's history. Under the command of the Earls of Buchan and

Wigtown, they fought valiantly; and it was to them in great part that

Charles owed his victory. The two armies were separated by a rapid

river, crossed by a narrow bridge. On the 23d of March the Scottish

general had sent a detachment, commanded by Sir John Stewart, of

Darneley, and the Sire de Fontaines, to reconnoitre. This troop, coming

upon the English unawares, fell back in time to warn Buchan of the

approach of the Duke of Clarence. Happily he had a short time to make

ready for an advance, whilst Sir Robert Stewart, of Ranston, and Sir Hugh

Kennedy kept the bridge with a small advanced corps, over which the Duke

of Clarence with his best officers tried to force a passage, having left

the great bulk of the army to follow as best they could.

The effects

of this rnaneuvre were, by a strange coincidence, the same as at the

battle of Stirling, where Wallace defeated Surrey and Cressingham. The

Duke of Clarence, conspicuous by the golden crown surmounting his

helmet, and by his gorgeous armor, was first attacked vigorously by John

Kirkrnichael, who broke his lance on him; then wounded in the face by

William Swinton; at last brought to the ground and killed by a blow of a

mace by the Earl of Buchan. The bravest of his knights and men-at-arms

fell with him. The Earl of Somerset was taken prisoner by Lawrence Vernor, a Scot; and his brother by Sir John Stewart of Darneley; the

Earl of Huntington by John Sibbald, a Scotch knight; and the Sire de Fewalt by Henry Cunningham.

The rest, furious at the disaster, rushed

to the bridge to take revenge; but they were killed or taken prisoners,

as they arrived, by the Scots. According to Monstrelet, two or three

thousand English lay dead on the spot. As might have been expected, the

Scots were, at first, regarded with dislike and contempt by the French

people. Owing to their habits of enforced abstemiousness at one time,

and the excesses in which they indulged at others, they were denounced

to Charles as sacs a yin et manguers de mouton. Charles paid but little

heed to these murmurs; but after the battle of Bauge he summoned the

accusers before him and said:

"What think ye now of these Scotch

mutton-eaters and vindhags?" "The malcontents," says the quaint

chronicle, as if they had been struck with a hammer on the head, knew

not what to reply." At Verneuil, in 1424, the English gained a bloody

victory, but the Scots fought to the last with stubborn determination.

The French were exhausted and terrified; the royal cause seemed almost

hopeless. Charles VII. had few whom he could trust, and the personal

loyalty of the Scottish mercenaries was the strongest support on which

he could lean. The traditional account that the Scots Guards was

established after the battle of Verneuil is confirmed by Mr. Forbes

Leith's researches into the Registres de la Chambres des Comics. On July

8th, 1425, the first mention is found of a body of men-at-arms and

archers ordained to guard the person of the king, under the command of

Christin Chambre, Esquire, of Scotland. When Joan of Arc began her

heroic struggle, the Scots warmly devoted themselves to her service. One

Scottish soldier, Walter Bowe, returned to his native land after Joan's

death, and became a monk at Inch Colme, where he continued Fordin's

Chronicle and commemorated the deeds of Joan, "whom I saw and knew, and

in whose company I was present to her life's end." In all the work of

the recovery of France the Scots took a prominent part, till the throne

of Charles VII. was secure. But when peace was re-established soldiers

were a hindrance to the national security. Bands of freebooters ravaged

the country, and the work of restoring internal order was as difficult

as that of securing peace. A happy chance gave Charles VII. the

opportunity of sending 30,000 soldiers to help Frederick III. to

prosecute the quarrel of the house of Austria against the Swiss. In this

expedition they suffered greatly from the vengeance of the peasantry,

which they awakened by their ravages. When the remnant returned to

France Charles VII. was ready to strike a blow against military licerise.

Many were dismissed from service, and the rest were formed into fifteen

contpagizics d'ordonnance, which were the beginning of the French

standing army. Two of these companies were formed from the Scots—"Les

Gendarmes Ecossais" and "La Conipagnie Ecossaise de Ia Garde due Corps

du Roi."

The services done by Scotsmen to France naturally caused many

honors to be conferred upon them. In 1422 John Stewart, Earl of Buchan,

was made Constable of the kingdom, and a year later, Archibald, Earl of

Douglas, was created Duke of Turenne. Both these heroes were killed,

fighting for their adopted flag at the battle of Verneuil. In 1424 a

large number of Scotch soldiers arrived in France under the charge of a

warrior named David Patullo, of whose exploits we know nothing, but they

must have been extraordinary, for in that year Sir John Stewart of

Darnley, another Constable of France, was invested with the lordship of

Aubigney, and created a Marshal of France. During the defense of New

Orleans the bishop of the See of Orleans was a Scot named John

Kirkmichael, who appears to have been as brave a soldier as he was a

good priest. While the siege lasted the bishop and the Scottish

residents greatly distinguished themselves by their valor. When Joan

of Arc made her way to the beleagured city she was accompanied by Sir

Patrick Ogilvy and a large number of Scottish soldiers, and when the

siege was ended the French heroine and the Scottish bishop headed the

procession that went from church to church and returned thanks to the

Almighty for their deliverance. When King Charles was crowned at Rheims,

bishop Kirkmichael was one of the consecrating clergy. Bernard Stewart,

of Aubigne, probably enjoyed more honors than any other Scot in France.

He was twice sent to Scotland as a special ambassador from France, and

fought in 1485 on the winning side at the battle of Bosworth Field in

England. His career in campaigns in Italy and Spain won him the greatest

reputation as a soldier. He was known as the "Chevalier sans reproche."

and Dunbar, the Scottish poet, styled him "the Flower of Chivalry."

Among other dignities he held those of Viceroy of Naples, Constable of

Sicily and Jerusalem, and Duke of Terra Nova. His second embassy to

Scotland was in 1508 to the court of James IV. who received him with

much distinction. But his health was then broken, and shortly after

being received at court he retired to Corstorphiue, near Edinburgh,

where he died. By his will he directed that his heart should be sent to

St. Ninian's shrine in Galloway, and his body buried in the church of

the Blackfriars at Edinburgh. These directions appear to have been

faithfully carried out. In 1548 Henry I. conferred the Duchy of

Chaterherault on the Earl of Arran, and that title is still held by the

Scotch ducal family of Hamilton.

In "Memories of the Ancient Alliance

between the French and Scots," printed at Edinburgh in 1751, I find the

following:- "With regard to offices, the Scots have exercised some of

the most considerable in France. Mr. Servien, a famous advocate under

Henry III., in his pleading before the parliament of Paris relates that

Mr. Turnbull, a Scotsman, was a judge in the same parliament, and

afterwards first president of the Parliament of Rouen, Adam Blackwood

was a judge on the bench of Poitiers, and others in courts of justice.

The Scots have also possessed in France some of the first dignitaries of

the church. Andrew Foreman was Archbishop of Bruges, David Bethune,

Bishop of Mirepois, David Panter (or perhaps Panton) and after him James

Bethune, Bishop of Glasgow, were successively abbots of L'Absie, besides

a great number of priors, canons, curates and other beneficed persons in

France. And it is remarkable that, in the year 1586, the cure of St.

Come at Paris having been conferred by the University upon John

Hamilton, haying been disputed him by a French ecclesiastic who

protested against Hamilton as being a Scotsman, Hamilton's cause was

pleaded in the parliament of Paris by Mr. Servien, who proved that the

Scots enjoyed the right of denizens, and in consequence by decree of the

court the provisional possession of the cure was adjudged to Hamilton."

William Barclay, a native of Scotland, was professor of law at Pont a'

Mousson in Lorraie, where he died in 1605. His son John, a poet and

satirist, accompanied him on a visit to Britain in 1603, and soon

attracted the attention of James VI., to whom he dedicated a volume of

satirical romance in which the Jesuits were severely handled. His

principal work "Argenis," apolitical allegory, was translated into

English three tunes, as well as into several other languages. Barclay

died at Rome in 1621.

An Act of Louis XIV.'s Council of State, signed

at Fontainebleau in 1646 specially exempted the Scots from the taxes

then imposed upon foreigners, as that exemption had been neglected in

the statutes governing these taxes. In the preamble to this act the

story of the Scottish friendship with France and the privileges extended

to natives of Scotland are thus stated: "Whereas it bath been

represented to the King, in his Council, the Queen Regent his mother

present, that in the year 789, Charlemagne reigning in France, and

Achius in Scotland, the alliance and confederacy having been made

between the two kingdoms, offensive and defensive, of crown and crown,

king and king, people and people, as is set forth by the Charter called

the Golden Bull, it should have until this present continued without any

interruption, and been ratified by all the kings, successors of the said

Charlemagne, with advantages and prerogatives so peculiar, that not only

are the Scots in capacity of acquiring and possessing estates, movable

and immovable and benefices in France, and the French in Scotland,

without taking out any letters of naturalization; but also it should

have been granted to the said Scots to pay only the fourth part of the

duties upon all goods which they transport to the said country of

Scotland a privilege which they have ever enjoyed, and do enjoy at this

day; that even whatever rupture there may have been between the crowns

of France and England since the Union of the kingdom of England with

that of Scotland, the French have nevertheless been still treated by the

Scots as friends and confederates."

In M. Francisque Michel's

magnificent work on the "Scots in France," we find that in the 16th and

17th centuries; noble French families were as proud of being able to

trace their descent from a member of the Scots Guards as an English

baron is to boast of his family having landed in England with the

Conqueror. Maximilian de Bethune, the Duke of Sully, imagined himself to

descend from the Beatons of Fifeshire and the great Colbert from the

Cuthberts of Inverness. The same veneration for Scottish ancestry is

shown in France even in our own times. The Empress Eugenie. wife of

Napoleon Ill., was proud of her descent from the family of Kirkpatrick,

and Marshal Canrobert, one of the most honored soldiers of the second

Empire commenced his genealogical tree in Scotland. Some years ago, M.

Leon Scott, an employe in the publishing house of M. Didot, Paris,

claimed to be the lineal descendant of Michael Scot of Balwearie,

Fifeshire, whose fame as a scholar and magician extended over the whole

of Europe from the 12th century. Whether Al. Leon Scott's claim to long

descent was proven or not, he could have the satisfaction of knowing

that his "case" was no weaker than that of Lord Eldon, who claimed to be

the direct descendant of the wizard and exerted all his legal argument,

logic, and perseverance to verify it. The descendants of the royal

family of Stewart made their way all over the continent and can be

traced among many of the reigning families of Europe. The royalist

princes of France have all Stewart blood in their veins, and the

heir-at-line of the old house, as well as of the English house of Tudor,

is Maria Teresa, wife of Prince Louis of Bavaria, neice of the last of

the Dukes of Modena in Italy.

In Russia, Scottish seekers after

fortune have also made their way to success and come out well ahead in

competition with the natives of that great, if somewhat barbarous,

country. Early in the 17th century a Scotsman, named George Lermont,

left his native land and settled at Belaya. in Poland. Thence he passed

into Russia and entered the service of Michael Feodorovick, the first of

the Romanoff czars, by whom he is mentioned in a paper dated March 9th,

1621. His descendants Russified their name by the affix "of," making the

name Lermantof, and the most famous among them was Michael Andreevich

Lermantof, who ranks as one of the foremost poets of Russia. The

Scottish origin of the family is acknowledged with pride by its members,

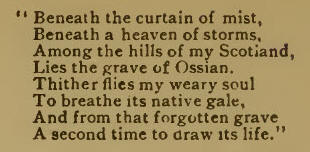

and the poet, in one of his pieces, says:

In another poem, entitled

''The Wish," he longs to have the wings of the bird, that he might fly

"to the west, where shine the fields of my ancestors," and where, ''in

the deserted tower, among the misty hills, rests their forgotten dust,"

And the chords of the harp of Scotland would I touch,

And its sounds

would fly along the vaults

By me alone awakened. by me alone listened

to,

No sooner resounding than dying away."

But such fancies are

vain, for

Between me and the hills of my fatherland

Spreads the waves of seas;

The last scion of a race of hardy warriors

Withers away amid alien snows."

Probably the best representative of

the Scottish soldiers of fortune who made Russia the scene of their

operations was General Patrick Gordon. This brave soldier and capable

general was born at Easter Auchlenchries, in 1635. His father was a

cadet of the house of Haddo, and was blessed with the possession of a

small and heavily mortgaged estate. When 16 years of age he was sent to

Dantzig, and entered the Jesuit college at Braunsberg, but the quiet

life of that seminary did not suit his roving disposition. In 1655 he

entered the Swedish service and embarked under its flag in its war

against Poland. Taken prisoner by the Poles he entered their service and

fought as gallantly against the Swedes as he formerly did for them. The

Swedes re-captured him, and without much ado he again drew his sword in

their service. A real soldier of fortune truly, and even more

unconcerned as to his allegiance than Sir Dugald Dalgetty. He rose,

however, to the rank of captain-lieutenant, and as such he offered his

services in 1661 to the Czar of Russia, and the offer was at once

accepted. His rise in the Russian army was rapid, and in 1665 he was

made a colonel. Then having learned of his accession to the grim and

poverty-stricken estate of Auchlenchries, a fit of home-sickness came

over him, and he desired to retire from the service and settle down at

home as a laird. But this the Czar would not permit, although in the

following year he sent him on a political mission to England. In 1670 he

fought in the Ukraine against the Cossacks, and seven years later he was

fighting the Turks. For his services in this last campaign he was made a

major-general, and in 1683 a lieutenant-generalcy was conferred upon

him. He was sincerely beloved by Peter the Great, and received many

marks of that monarch's affection but none more than were warranted by

his devotion and services to the greatest of all the czars, whose life,

indeed, he at one time saved. Gordon's latter years were spent in

opulence at Moscow, and he died in that city on eve of St. Andrews Day,

1699. Speaking of his last moments, one of his biographers says, ''The

czar, who had visited him five times in his illness, and had been twice

with him during the night, stood weeping by his bed as he drew his last

breath; and the eyes of him who had left Scotland a poor unfriended

wanderer, were closed by the hands of an emperor."

Another old

Aberdeenshire family, the Barclays of Tolly from the same stock out of

which sprang the Barclays of Ury—had its representatives in the Russian

service. The founder of the Russian family seemed to have prospered, and

unlike Patrick Gordon relinquished all interest in his native land. One

of his descendants, Michael Barclay de Tolly, after a brilliant military

career, became commander-in-chief of the Russian armies in France at

the time that the allied powers of Europe were closing in upon the great

Napoleon, and in recognition of his services was created a prince and

appointed field marshal. He died in 1818. Shortly before his death, the

old family estate of Tolly came into the market and he was urged to

purchase it. But he declined as he thought that the family had been so

long expatriated from Scotland as to retain no interest in it.

Peter

the Great, in his task of creating a navy, was greatly aided by

Scotsmen. The services of Paul Jones to Russia are still remembered, and

among physicians and professional men generally, natives of Scotland

have carried off many of the leading honors. The stories of the Scottish

soldiers of fortune, cadets of noble houses, who left their native

country and the poverty to which their birth doomed them at home, and

won honor for their names and their native laud on the continent of

Europe, are full of chivalry, romance, bravery, devotedness and

sometimes pathos. These men were not all Dugald Dalgettys, as we are so

apt to regard them, since Sir Walter Scott, by his genius, made that

chevalier a representative of the race. Notwithstanding all his faults,

however, the Knight of Drumthwacket was not altogether an unlovable

personage. He was a man of undoubted courage, although he had a full

share of the logical cautiousness of his country people; he was vulgar

in his manner, but he was honest as steel to whatever flag he agreed to

serve under; he was talkative and prosy, but when the proper time came

he was full of resource and action; he possessed no statecraft, but he

was more than a match for the Earl of Argyll, who imagined he had enough

of that quality to endow the whole of Scotland; and his word was as good

as his oath, whether given to the Marquis of Montrose or to old MacEagh

of the Mist. Notwithstanding his shortcomings, there remains enough

about Sir Dugald to make us think about him as a representative soldier

of fortune without believing that thereby the honor of the race was

imperiled. Few, very few, of these adventurous Scots ever returned to

their native land again after buckling on their swords and leaving it in

search of fame and fortune. War was a game that was constantly being

played in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries, and the excitements

and dangers of these times stifled effectually the craving of

home-sickness which so often comes over the Scot Abroad. The

battlefields of Low Germany proved the last resting places of many of

them, and to those few who survived the dangers of the field, and

perhaps found themselves in possession of the fortune for which they

started, the changes which met them when they returned to Scotland too

often made it no longer a desirable resting place, with memories of what

had been and what might have been, constantly before them. This is to me

the saddest phase in the lot of the Scot Abroad. I have known men, and

women too, toil hard year after year in this country and gradually

acquire a competency. Then, when it was won, the long suppressed

yearning for home would break out with extraordinary force, and the idea

expressed in Allan Cunningham's touching song would constantly he with

them:

"Haute, haute, haute. haute fain wad I be,

O

haute, haute, hame to my ain countrie.

* * * * * * *

When the flower is i' the bud and the leaf upon the tree,

The lark

shall sing me hame in myain countrie."

The wanderer at length goes

home to find it home no longer. Friends and relatives have died or

wandered away to other parts of the earth, old landmarks have

disappeared or changed, and the place that knew the wanderer now knows

him no more. To walk along well-remembered streets, to stand on the very

stones one played over when a boy, to see this little reminder of

youthful plays or that oft dreamed of nook, and not to see a "kenned

face" or get a smile from an acquaintance of auld lang syne is about as

bitter an experience as can come to any human being. I remember an old

farmer in Michigan, who visited Dumfries after an absence of forty-six

years, telling me of his experiences with a sad heart on his return

here. The first day after his arrival he remained in his hotel, tired

and worn out from the effects of his journey, but with a feeling of

self-satisfaction that he was once more, at hame. Next day he wandered

about the town, and in the leading streets, the changes were so great

that hame began to seem as far away from him as it was in America. In

the by-ways, the lanes, and wynds, time had made fewer alterations, but

still enough had occurred to show that the laws of mutability governed

even Dumfries. Then he spent several days enquiring after old

schoolmates and playfellows, but never gained an answer which gave him

the satisfaction he desired. "he's dead," "The whole family went to

Australia," ''They were last heard of in Canada doing well " He went to

London and never came back," were some of the answers he received, but

the most general was "Never heard o' them." The place that afforded him

the most information was auld St. Michael's kirkyard, for on many of the

tombstones of that hallowed God's-acre he read the names and recalled to

his memory a large number of the lights of his own day. But that day was

over now, the dream of hame so carefully nursed for nearly half a

century was dissipated forever, and the old man turned his face from his

native city sad at heart, broken in spirit, a wanderer without a home.

The late Dinah Muloch Craik expressed this sensation very beautifully in

her little poem entitled, "Coming Home."

The lift is high and blue,

And the new moon glints

through

The bonnie corn-stooks o' Strathairly,

My ship's in

Largo Bay,

And I ken it weel the way

Up the steep, steep brae o'

Strathairly.

When I sailed ower the sea,

A laddie

bold and free,

The corn sprang green on Strathairly.

When I come

back again,

'Tis an auld man walks his lane,

Slow and sad through

the fields o' Strathairly.

* * * * *

O, the lands'

fine, fine!

I could buy it a' for mine;

My gowds yellow as the

stooks o' Strathairly

But I fain yon lad wad be,

That sailed ower

the salt sea,

As the dawn rose gray on Strathairly."

It is

needless, almost, to say that the Scots who became soldiers of fortune

were all possessed of high courage and most of them were men of as pure

chivalry and as noble aspirations as any knight who ever followed Bruce

at Bannockburn or accompanied the Douglas when he started on his way to

the Holy Land with the heart of his hero in charge. In a volume by John

Mackay, of Herriesdale, entitled "An old Scots' Brigade," and published

at Edinburgh in 1885, is given a history of Mackay's Regiment and the

Scots Brigade which was organized in 1626 and served under Gustavus

Adolphus, the famous king of Sweden, during part of the Thirty Years'

war. This volume is full of stories of daring deeds and of acts of

heroism which should inspire a feeling of pride in every Scottish

reader, and it shows that a true chivalrous spirit animated all these

gallant soldiers of fortune from the titled chief himself down to the

humblest private who trailed a pike. The following account of the

defense of Boitzenburg in 1627 by a handful of the men of this command

may be regarded simply as an example of a long list of equally brilliant

achievements. "On the third day after the departure of Sir Donald Mackay

with the main portion of the regiment, the approach of the enemy was

announced. But Major Dunbar afterwards killed at the defence of

Bredenburgh had not been idle. He was well versed in the theory as well

as in the sterner practice of war and had every qualification for a

commander. He left nothing undone that would enable him to defend his

post like a man of honor. He undermined the bridge, repaired the weak

places in the walls, and erected a strong sconce on the Luneberg side of

the town. This sconce the enemy resolved to storm. Once across the Elbe,

the rich and fertile plains of Holstein could be easily overrun and

would be entirely at their mercy. The small garrison of Highlanders

numbered only about 800 men while the attacking force was at least

10,000 strong. The first night a gallant and successful sortie was made

under the personal leadership of Major Dunbar, and after inflicting a

severe punishment on the advanced posts of the lmperialists, the little

band returned to the town with scarcely any loss. The enemy were

determined to be avenged for this, and on the following day attacked the

sconce at all points, but after a long and desperate struggle were

beaten off with a loss of over 800 men. But fresh troops were pressed

forward, and again the attack was renewed with increased fury; the front

rank rushed on, and with hatchets attempted to force a passage through

the palisades; then the artillery opened fire, and every now and then a

heavy cannonshot would boom overhead or crash among the roofs of the

houses, or with a dull heavy thud, sink into the turf breastwork of the

sconce. The defenders replied with their brass culverins, and every shot

must have made a frightful lane through the dense column of attack. A

close and deadly fire, too, was poured by the Highland musketeers upon

the Imperialists and though the latter replied with equal rapidity yet

could not with equal effect, for the Highlanders were protected breast

high by the earthen parapets, while the assailants were wholly exposed.

The whole fort was soon enveloped in smoke, the enemy could not be seen,

but the crash of their axes was heard among the falling palisades and

the cries of the wounded told of the fearful carnage. The Imperialists

were baffled and again fell back. But a third and even more desperate

attempt was made to carry the sconce. * * * The storming parties came on

in great force and made a most vigorous assault, but the firing of the

Highland musketeers once more told with deadly effect. The thunder of

the enemy's artillery was incessant, yet the shot did more damage to the

houses of the deserted town than to the earthworks of the sconce. Again

the culverins were brought into play, and, under Dunbar's directions,

did dreadful execution on the Imperialists, but in spite of this they

continued to press on, and the gaps made in their ranks by the well-drected

fire of the Highlanders were constantly and steadily filled up. The

loss, however, was not all on the side of the enemy, many of the

defenders were killed and a large number wounded. But after a time the

firing of the Highlanders slackened and then suddenly ceased. Their

supply of ammunition was exhausted The Imperialists, surprised at the

unexpected silence on the part of the (le- fenders, instinctively

guessed the cause and redoubling their efforts, made a rush at the

walls. The Highlanders, for a moment, were at their wit's end, but the

energy of despair prompted them. They tore the sand from the ramparts,

and threw it in the eyes of their assailants as they attempted to scale

the walls, and then furiously attacking them with the butt ends of their

muskets, drove them from the sconce. But it was a dreadful struggle. At

last the trumpets of the enemy sounded the retreat, the storming party

fell back, the fire of the artillery ceased and Boitzenburg was saved."

Instances of individual heroism on the part of Sir Donald Mackay, Sir

John Hepburn and the officers and men under their charge are frequently

given in the same work, and after the battle of Leipzig the Scots

Brigade was publicly thanked by Gustavus Adolphus for its brilliant

services in presence of the whole army. Even the chaplains were soldiers

of fortune as well as preachers. One of them, whose name is not

recorded, was massacred when the castle of Bredenbnrg was taken by Tilly.

Another, the Rev. William Forbes, is described in the old record very

significantly as ''a preacher for soldiers, yea and a captaine in neede,

to lead soldiers on a good occasion, being full of courage and

discretion and good conduct beyond some captaines I have known who were

not so capable as he." This good man managed to escape the perils of war

and became minister of the Scots Church at the Hague, where he died. A

third chaplain was the Rev. Murdoch Mackenzie, afterwards minister of

Suddie, Ross-shire, and one of the Commissioners to the Assembly in

1643, 1644 and 1649. In the course of their campaign the Highlanders met

with many of their countrymen, who like themselves were in search of

fame and fortune on the continent. At Urbowe in Sweden, they encountered

"that worthy cavalier Colonel Alexander Hamilton, being then imployed in

making of cannon and fire-workes for his majesty." This gentleman, Mr.

John Mackay informs us, was Sir Alexander Hamilton, of Redhouse, a

celebrated artillerist, whose cannon were long famous in Germany and

guns made on his principle and known as canon ci la Suedois were used in

the French army till 1780. He returned to Scotland, became famous in the

wars of the Covenant and was killed by an explosion at the castle of

Dunglass." Sometimes these fighting Scots were brought face to face with

their own countrymen fighting on the opposite side. The same writer says

"It must have been trying to our countrymen to encounter brother Scots

in the forces to which they were opposed, but when Passions are aroused,

even the closest ties are sometimes forgotten. Munro gives an instance

of this. He says 'There was a Scottish gentleman under the enemy who,

coming to scale the walls, said aloud, 'Have with you, gentlemen, thinke

not you are in the streets of Edinburgh bravading;' one of his own

countrymen thrusting him through the body with a pike, he ended there.'

He ended there is rather a quaint way of saying that the wound inflicted

was mortal. But this is only one of the horrors of war.''

The Scot

Abroad, however, was not always so fortunate as to win battles, found

families, or even to maintain positions of honor, and a painful

illustration of this is furnished by the career of Alexander Blackwell,

a native of Aberdeen, where his father was a minister and principal of

Marischal College. Blackwell studied medicine and graduated at Leyden.

We next hear of him as being engaged in business in London as a printer.

This venture was not successful, and in 1734 he became bankrupt and was

thrust into prison. During his incarceration his wife supported him by

her literary labors and eventually secured his discharge. In 1740 he was

invited to settle in Sweden, one of his works having attracted the

attention of the king of that country, and, proceeding to Stockholm, he

received a pension and was otherwise comfortably provided for. His

medical knowledge was of value to him in his new sphere, and having

cured the king of a serious malady he was appointed one of the royal

physicians, and became an influential favorite at court. In 1748,

however, he was suddenly arrested on a charge of treason against the

king and the government, and after being tortured was broken on the

wheel. He protested his innocence to the last and was doubtless a victim

to the jealousy of some of those whom he had eclipsed in the royal favor.

The most illustrious of the Scottish soldiers of fortune who won renown

on the continent of Europe was Field Marshal Keith. This warrior was the

second son of ninth Earl Marischal of Aberdeenshire. Along with his

elder brother he took part in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715, and being

on the losing side, made his escape to France, when that ill-concocted

rising was suppressed. The family estates were confiscated, the title

was attainted, and the brothers found themselves poor as well as

landless. In 1719 they returned to Scotland on one of the ships of the

fleet sent by the Spanish court to restore the Stuarts, and after the

defeat of the Highland Jacobites and their foreign auxiliaries were glad

to escape again from their native land. The elder brother entered the

Prussian service and attained a position of both honor and emolument. In

1759, while ambassador from Prussia at the court of Spain, he was

pardoned by the British Government in return for some political secrets

which he communicated. Soon afterwards he returned to Scotland on a vsit,

and purchased a portion of the old estate of his family, but declined to

receive back the attainted family titles. He died in Prussia in 1778.

His brother James (Marshal) Keith, after making his escape from Scotland

in 1719, entered the Spanish service, but one of his adherence to

Protestantism was debarred from advancement. Then he profferred his

sword to Russia and received a commission as major-general. In the

Russian military service Keith acquired much distinction, but finding it

not exactly to his liking he transferred his allegiance to Prussia in

Frederick the Great received him gladly and conferred on him the baton

of a field marshal. From that time until his death he seems never to

have sheathed his sword, and his services were equally brilliant whether

in the decisive victory at Rossbach, or in the midst of disaster and

retreat. His last battle was that of Hochkirch, in 1758, where the

Prussian army was defeated by the Austrian force, and Marshal Keith was

shot through the heart while gallantly fighting his way from the field.

The Scot Abroad has been as successful as a statesman as well as in the

more brilliant role of a soldier. An example of this is to be found in

the career of Principal Carstaires. That great and good man was born at

Cathcart, now a part of Glasgow, in 1649. He was educated for the

ministry at the University of Edinburgh; and in 1673 went to Utrecht

with the view of completing his theological studies. While in Holland,

his attainments and character drew to him the attention of William,

Prince of Orange (afterward William III.) and he became the confidant

and adviser of that ruler in regard to British affairs. In 1682 William

sent him to London on a secret mission, and while there he was arrested

for complicity in the Rye House plot, by which Charles II. and his

brother, afterwards James II., were to be murdered, and the succession

to the throne brought nearer to Mary, the wife of the Prince of Orange.

The plot was betrayed, Lord Russell and Algernon Sydney, two of its

reputed leaders, were executed. Lord Essex, another of the confederates,

committed suicide in the tower, the Duke of Monmouth fled to the

Continent, and many of those of lesser degree were brought to the

torture. Among the latter was Carstaires. It was known by the British

court that the Scotch clergyman enjoyed the entire confidence of the

Prince of Orange, and that he was in possession of state secrets of the

utmost importance at that critical juncture in the history of Britain.

Threats, or promises of reward, failed to make him reveal any of these,

and even the application of torture did not cause him to waver in his

fidelity to the Prince. The boot and the thumbscrew combined were not

equal to his fortitude. In 1685 he returned to Holland and continued to

watch carefully the state of opinion and the progress of events in

Britain until 1688, when on his advice, William went over to England and

carried out the Revolution. He crossed over from Holland in the same

vessel, and conducted, at the head of the army, the religious services

which marked the first day's occupancy of the soil of Britain, and

during the negotiations, movements and developments which followed, he

was the most trusted, as he was the most sagacious, honest, far-seeing,

and fearless of the new King's councillors and friends. When the affairs

of England were in a measure settled, Carstaires returned to Scotland,

and it was his wise influence, exerted on the king on the one hand and

the clerical party—the General Assembly—on the other that enabled

Presbyterianism to find itself finally established in Scotland on a firm

and enduring settlement, and made Episcopalianism forever an alien in

the land. With the return of Carstaires to Scotland and his subsequent

career there, this essay has nothing to do, as he no longer can be

regarded as a Scot abroad, but I cannot forbear from quoting the tribute

which Lord Macaulay has rendered to his memory. He says, in the History

of England (vol. 3, page 37, trade edition, New York) "William had,

however, one Scottish adviser who deserved and possessed more influence

than any of the ostensible ministers. This was Carstaires, one of the

most remarkable men of that age. He united great scholastic attainments

with great aptitude for civil business, and the firm faith and ardent

zeal of a martyr with the shrewdness and suppleness of a consummate

politician. In courage and fidelity he resembled Burnet, but he had,

what Burnet wanted, judgment, self-command and a singular power for

keeping secrets. There was no post to which he might not have aspired if

he had been a layman or a priest of the Church of England. But a

Presbyterian clergyman could not hope to attain any high dignity, either

in the north or in the south of the island. Carstaires was forced to

content himself with the substance of power, and to leave the semblance

to others. He was named chaplain to their majesties for Scotland, but

wherever the king was, in England, in Ireland, in the Netherlands, there

was this most trusty and most prudent of courtiers. He obtained from the

royal bounty a modest competence, and he desired no more. But it was

well known that he could be as formidable an enemy as any member of the

cabinet, and he was designated at the public offices and in the

antechambers of the palace by the significant nickname of the Cardinal."

In the learned and literary circles of the continent of Europe, among

the thousands of Scots who thronged the universities or walked in the

dim and barred recesses of the cloisters, none acquired so much fame, or

is held in fresher remembrance, than James Crichton, commonly spoken of

as "the Admirable Crichton," and "the Sir Philip Sydney of Scotland."

The achievements recorded of this personage are really marvelous, but it

is merely fair to say that, to a great extent their only authority is

tradition, and that around his memory the glamour of two centuries of

romance and poetry has been thrown. He left behind no writings by which

we might judge of his literary attainments, and the extravagant eulogies

of most of his biographers almost make one feel inclined, sometimes, to

doubt his very existence, were that fact not amply confirmed. At the

same time the old proverb which says that where there is smoke there is

sure to be a fire, rises to our memory, and we may well believe that to

have won so much personal fame of an enduring quality, James Crichton

must have been possessed of many grand qualities and to have towered

intellectually far above most of his contemporaries: He was born about

the middle of the 16th century, and was the son of Robert Crichton, of

Elliock, Perthshire, Lord Advocate of Scotland from 1561 to 1573. He was

sent to the University of St. Andrews, and before he reached his

twentieth year had exhausted all the educational possibilities of that

seat of learning. He became thoroughly acquainted with all the then

known sciences and was master of ten languages. But in addition to all

these acquirements, the possession of which would have occupied an

ordinary lifetime, Crichton was an adept in all manly sports and the

very embodiment of an accomplished knight. He left his native land and

wandered over the continent in search of learned encounters with the

talented men of the universities, but failed to find one whom, in a

discussion on theology, philosophy, morals or science, he could not

easily overthrow. his "disputations" at such centres of thought as

Paris, Venice, Padua, Mantua and Rome excited amazement, and wherever he

went great crowds of students gathered to listen to the wondrous words

of wisdom which fell from his lips, and to observe the ease with which

he refuted the arguments of his learned opponents. Being possessed of

remarkable personal beauty and having all the exterior accomplishments

which used to make up a chivalrous gentleman, it may easily be

understood that Crichton was a favorite with the ladies, and one of his

love affairs led him to fight a duel with a gentleman who was regarded

as the most famous of Mantua's warriors. Crichton in this encounter was

successful, and so added to his reputation that of being a gallant

knight. Such a prodigy as this could not live long, and his very

excessive observance of chivalrous courtesy brought about his end. The

Duke of .Mantua appointed him preceptor to his son Vincentio, a

dissolute young scamp. One night, when engaged in a love adventure,

Crichton was attacked in a side street by half a dozen men in masks, but

he routed them so successfully that their leader threw off his disguise

and begged him to desist. Crichton saw that his opponent was none other

than his pupil Vincentio, and dropping on his knees, begged forgiveness

and offered his sword. Vincentio took the weapon, and at once plunged it

into Crichton's body, killing him on the spot.

It is possible that the

talents and courage ascribed to Crichton by tradition, are a sort of

tribute to the fair fame of the Scots nation in Europe, particularly in

intellectual circles. That Scottish scholarship ranked high on the

continent during the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries, there is no reason

to doubt. In Tytler's "History of Scotland" we read :"Scotland produces

scholars whose reputation stood high in the schools [of theology].

Richard, a prior of St. Victor's at Paris, and Adam, a canon regular of

the Order of Preinonstratenses, illuminated the middle of the thirteenth

century by voluminous expositions upon the Prophecies, the Apocalypse

and the Trinity; by treatises on the threefold nature of contemplation;

and soliloquies on the composition and essence of the soul; while during

the second age of the scholastic theology, John Duns delivered lectures

at Oxford to thirty thousand students. In the exact sciences, John

Holybush, better known by his scholastic appellation, Joannes de

Sacroboseo, acquired during the thirteenth century a high reputation

from his famous treatise on the Sphere, as well as by various other

mathematical and philosophical lucubrations, and although claimed by

three different countries, the arguments in favor of his being a

Scotsman are not inferior to those asserted by England and Ireland.

The consequent resort of [Scottish] students to France led to the

foundation of the Scots College at Paris in the year 1325 by David,

Bishop of Moray—an eminent seminary which was soon replenished with

students from every province in Scotland. * * * The records of the

University of Paris afford evidence that, even at this early period, the

Scottish students had not only distinguished themselves in the various

branches of learning then cultivated, but had risen to some of the

highest situations in this eminent seminary."

In St. Giles' Cathedral,

Edinburgh, is a brass memorial tablet bearing the following

inscription:-"In memory of John Craig, for many years a Dominican friar

in Italy; embraced the Reformed faith, and was by the Inquisition at

Rome condemned to be burnt; escaping to his native country, he became

assistant to John Knox at St. Giles', and minister of the King's

household. He was author of the King's Confession, or National Covenant

of 1581. He died in Edinburgh in his eighty-ninth year." The inscription

is surmounted on the left by the figures 1512, and on the right by

1600—the dates of his birth and death—while in the centre is a

representation of a dog carrying a purse in its mouth, with the words

"My all." John Craig, before going to Italy, was a Dominican friar in

his native Scotland, but was suspected of heresy and lodged in prison.

He managed to be released, and, retaining his standing in the church,

went to Italy; and at Bologna was intrusted with the education of

novices. A perusal of Calvin's Institutes converted him to

Protestantismn and he openly avowed his acceptance of the new doctrine.

Pope Paul IV. sent him to the Inquisition at Rome, and there he was

condemned to be burnt on 19th August, 1559, but on the 18th the Pope

died, and being very unpopular, great riots occurred that evening in the

city, in course of which the mob broke his statue in pieces and set fire

to the Inquisition buildings. Craig then escaped, but was pursued by a

hand of Papal soldiers who came upon him. The leader, however, turned

out to be an old soldier whom Craig had once befriended, and instead of

capturing he assisted him to escape. He then had many weary wanderings,

trials, and narrow escapes. The incident of the dog, commemorated on the

tablet, is so marvelous that in these matter-of-fact days it will

scarcely be credited. Even Spottiswoede in narrating Craig's life seems

to have entertained doubts of the story being believed, and says:- "I

should scarce relate, so incredible it seemeth, if to many of good place

he himself had not often repeated it as a singular testimony of God's

care of him, and this it was. When he had traveled some days, declining

the highways out of fear, he came into a forest, a wild and desert

place, and being sore wearied he lay down among some bushes on the side

of a little brook to refresh himself. Laying there pensive and full of

thoughts (for neither knew he in what he was, nor had he any means to

bear him out of the way), a dog cometh fawning, with a purse in his

teeth, and lays it down before him. He, stricken with fear, riseth up,

and looking about if any were coming that way, when he saw none, taketh

it up, and construing the same to proceed from God's favorable

providence towards him, followed his way till he came to a little

village, where he met with some that were traveling to Vienna, in

Austria, and changing his intended course, went in their company

thither."

Leaving Europe, we find that Scotsmen have played an equally

important part in Asia. In India especially their services have been of

the utmost importance in upholding the supremacy of the British flag, as

well as in developing the moral, intellectual and commercial progress of

the land. India was, and is, a country of great chances and the Scots

have taken full advantage of its opportunities. It is said that a Perth

man once landed in Calcutta in search of fortune. He knew no one, but

remembering that a schoolmate named McNaughton held a post under the

East India Company, he hastened to the Government Building and entering

its court was overcome by its extent and the evident number of its

occupants. Not knowing what else to do, he stood in the centre of the

square and called his old friend by his school-boy name—"Mac Mac!" and

immediately a head, sometimes two or three, appeared at each window and

a chorus of "What d'ye want?" startled the visitor. They were all

"Macs."

In the list of Indian administrations that of the Marquis of

Dalhousie, from 1848 to 1855, stands out pre-eminent for its devotion to

the best interests of the country. Under his wise leadership many

magnificent public works were inaugurated, a cheap rate of postage was

introduced, railways and telegraphs began to bring the people nearer to

each other, splendid roads were laid out through the interior, and

canals were opened. The social progress of the people was as earnestly

regarded by this prince of administrators as any other of the details of

wise government, and many reforms were instituted. But although the arts

of peace were thus industriously fostered, the more brilliant deeds of

war were not wanting to complete the record. A Sikh campaign, and one in

Burmah, swelled the roll of Britain's Eastern triumphs and four great

kingdoms—Punjab, Pega, Nagpur and Oude, were annexed to the Indian

Government. Lord Dalhousie (the Laird o' Cockpen) was born at Dalhousie

Castle, near Edinburgh, in 1812, and died there in 1860, at the

comparatively early age of 48 years, leaving behind him a name which

must ever retain a prominent position in the history of modern India.

Among the Scottish heroes in India, one of the most prominent was Sir

David Baird, "the hero of Seringapatarn." He was born at Newbyth in

1757. In 1772 he entered the army. In 1778 he was made a captain in the

73d Highlanders (then just organized), and sailed with them to India.

His fighting career began in 1780, when Hyder Ali entered the Carnatie

and commenced a bitter war with the British. Towards the close of the

year one of the British armies was surprised in all and almost

annihilated. A few escaped death but were taken prisoners, and among

these was Captain Baird, whose valor in the struggle had won for him the

admiration of the European soldiers who acted among the officers of the

enemy. He was carried to Seringapatam and thrust into a dungeon. The

late Dean Ramsay, in his inimitable "Reminiscences," tells a story in

connection with this imprisonment which deserves to be retold. He says:

"Mrs. Baird, of Newbyth, the mother of our distinguished countryman, the

late General Sir David Baird, was always spoken of as a grand specimen

of the class (of old Scotch ladies). When the news arrived from India of

the gallant, but unfortunate, action of 1780 against Hyder Ali, in which

her son, then Captain Baird, was engaged, it was stated that he and

other officers had been taken prisoners and chained together two and

two. The friends were careful in breaking such sad news to the mother of

Captain Baird. When, however, she was made fully to understand the

position of her son and his gallant companions, disdaining all weak and

useless expressions of her own grief, and knowing well the restless and

athletic habits of her son, all she said was, 'Lord pity the chiel

that's chained to our Davy.'" The Dean, in a footnote to this anecdote,

says ''It is but due to the memory of 'our Davy' to state that the chiel'

to whom he was chained, in writing home to his friends, bore high

testimony to the kindness and consideration with which he was treated by

Captain Baird." The captives were released in 1784, and in 1789 Baird

was able to pay 4 visit to his native land, in 1791 he returned to

India, and after four years' further service found himself a colonel. In

1798 he received his commission as major-general, and next year led the

storming Party in the victorious assault on Seringapatarn. His services

on that occasion won him the admiration of the army and he received the

thanks of the British Parliament. In 1800 he commanded the troops in an

expedition to Batavia. During the remainder of his military career he

added to the prestige of the British nation at the Cape of Good Hope,

Copenhagen and Spain. In the latter country he served under a still more

famous Scot, Sir John Moore, a Glasgow man, and when that gallant

commander was killed at Corunna, Baird took command of the army. A short

time afterward he retired from the service. During his active career he

received the thanks of Parliament no less than four times. In connection

with the famous stronghold of Seringapatam the following may be deemed

of interest, as it is quite in keeping with the theme of this essay. Who

the author is I know not, as it came before me in the shape of a cutting

from some newspaper.

"Many years ago a landed proprietor in a mid-county of Scotland, whom

we shall call Stewart of Stewartfield, was outlawed for homicide, and

disappeared from the country, leaving no clue to his whereabouts. Time

rolled on; and there being still no tidings of the outlaw, his estate

was placed under judicial custody, for the benefit of his

representatives. After the lapse of many years the property was claimed

by a near relative, who became proprietor, and who, in default of direct

proof of the outlaw's death, is said to have tendered, on affidavit, the

following circumstantial evidence of it, as related by the late Colonel

Campbell of the 74th Highlanders.

When Seringapatam was invested by

the British forces in 1791, after the defeat of Tippoo Saib's army at

the battle of Mallavelly, the Sultan sued for peace. Accordingly, a

meeting of commissioners was arranged to take place within a

garden-house in the immediate vicinity of the fortress, to draw up a

treaty. The commissioners met; and while their proceedings were being

engrossed, Colonel Campbell, who was one of the British commissioners,

sat intently gazing at the Mohammedan commissioner who sat opposite to

him at the table. At length he exclaimed half-aloud to Colonel Edington,

another commissioner: 'If Stewart of Stewartfield is alive, that's the

man' pointing at the same time to his Mohammedan vis-a-vis. Although the

remark must have been heard by the Mohammedan commissioner he made no

sign; but on the breaking up of the conference, and as Colonel Campbell

was leaving the room, a voice whispered in English from behind him.

Don't look round, or it may cost me my life; but meet me alone, outside

the sally-gate at midnight tomorrow.' Notwithstanding the warning,

Colonel Campbell was startled by the occurrence, and involuntarily

looked round, and saw the same grave Mohammedan commissioner, whom he

had suspected to be Stewart of Stewartfield, moving off in an opposite

direction. Campbell kept the tryst at the spot name; but the other

party, whoever he was, never appeared. Cautious inquiries were

subsequently instituted about the individual in question; but nothing

was elicited; nor was he again seen or heard of by any of the British

officers to whom his features had previously been familiar. It was

surmised that his communication with the British officer in his own

tongue had been over- heard, and that probably he had been assassinated

as a traitor—the fate he had anticipated.

"Not once, but several times

have I seen a Scotchman inadvertently revealing himself under the garb

of a Turk. A few years ago a venerable Mussulman was to be seen daily in

the cool of the evening taking his solitary drive along the sea-beach at

Madras in his palanquin carriage. Of course he was looked upon as a

genuine son of the Prophet, until one day he was taken aback, as many

people are, by the exorbitant demand made upon him in an European shop

for some European article. His indignant feelings laughed at his

disguise, and asserted their nationality in the strong Scotch

expression: 'Gude save us; it's no worth a bawbee!' When on my way home,

and when on board a small Turkish steamer in the Bay of Alexandria, we

were having our luggage passed by two Turkish custom officers. I

scannedthe features of one of them, and ventured to say to my friend

Major F—, standing beside me: 'If I were a betting man, I would stake

something upon that Turk being a Scotchman.' The official heard me; and

with a cunning leer, he turned to his companion, and evidently for my

satisfaction, addressed him in the broadest Aberdonian dialect.

"A similar story is told of a Perth man who had penetrated into some

far interior of Asia—we forget where he had to see the Pacha, or

Bashaw. He was introduced to the great man in his tent. They gathered up

their knees, and sat down upon their Carpets. They drank their strong

coffee, and smoked their hookahs together in solemn silence; few words,

at any rate, passed between them, but, we may trust, sufficient for the

occasion. When the man of Perth was about to leave, the Pacha also rose,

and following him outside the tent, said, in good strong Doric Scotch 'I

kenned ye vera weel in Perth; ye are just sae-and-sae.' The Perth man

astonished, as well he might be, until the Pacha exclaimed, as he said,

'I'm just a Perth man mysel'! He had travelled, and he had become of

importance to the Goverment there. his story was not very creditable. In

the expectation of the post he filled, he had become a Mohammedan. But

he was an illustration of the ubiquity of his race."

Another Scot,

whose career had a greater influence upon India than is generally

acknowledged or understood, was Sir Alexander Burness, a native of

Montrose. His father, James Burness, was a cousin of Robert Burns,

"Scotia's darling poet." Burness entered the Indian service, and the

rapidity with which he acquired a mastery of the Oriental languages and

dialects marked him out for important service. In 1832 he was sent on

political mission into Central Asia, and, disguised as all passed

through Afghanistan to Persia, until he reached Bushire whence he

re-embarked for India. His mission was a successful one, and he was

publicly thanked by the Governor-General. In 1839 he was appointed

political agent or resident at Cabul, and was murdered in 1841 on

outbreak of an insurrection in that City.

These three names, including

the administrative, military and civil services, must suffice as

representative examples of the men which Scotland has furnished to

India. To go into detail and mention the Grants, Roses, Napiers,

Campbells and others, would require volumes. In fact to describe

completely the services rendered to India by Scotch men would

necessitate the writing of its history. And this reminds me that the

best history of India was written by James Mill, the son of a shoemaker

in Montrose, and the father of John Stuart Mill, the philosopher and

political economist.

On the sea as on land the Scot Abroad has added

to his country's laurels, although by no means to the same extent. This

is not a little singular considering the coast line of the country and

the large proportion of its inhabitants who daily go down to the sea in

ships—or fishing boats. But somehow the sea has always had a mournful,

mysterious significance for the Scot. The wild waves of the Atlantic, as

they clash with terrible impetuosity on the battered and gnarled western

coast, or the awful surges of the German sea as they throw themselves on

the eastern shore with deathlike venom arouse an eerie feeling in the

minds of the onlooker, and impress him with a dread of the power which

lies behind these forces and uses them as a child uses its toys. Then,

too, the water is full of treachery. A placid inland sea like the Holy

Loch, may be like a mirror beneath the sun, with hardly a ripple on its

glassy bosom, or a speck of foam on its fringes as they lazily lap its

shores. Then almost as by magic the sky will become dark, a gruesome

moaning will be heard, a sheet of lightning will flash across the lift,

the thunder will rattle and re-echo among hundreds of hills, and the

water be one ugly mass of struggling, seething, engrasping activity, in

which no swimmer or boat can hope to live, and which ruthlessly sucks

down into its greedy vortex all that was on its once placid surface.

Then, as suddenly as it came, the storm will vanish, the sun will resume

its monarchy in the heavens, and the water peacefully look up to it as

before. And so the story of treachery and desolation might be told of

firth and loch, and sea and river, from Solway Sands to Duncansbay Head.

The most prominent of the early mariners of Scotland was Sir Andrew

Barton, whose last sea-fight was made the theme of a stirring ballad

which is printed in Percy's "Reliques" and other collections. He

belonged to a family that had long been noted for their knowledge of the

sea and ships, so, when James IV., about the year 1509, made plans for

the building of a navy, they were his chief advisers. Under their

guidance the "Great Michael," one of the largest warships which the

world had then seen was built. Its dimensions may he guessed when we

find it stated that it carried 300 seamen and officers, 120 gunners, and

1,000 soldiers. One of Andrew Barton's early exploits was an attack on

some Dutchships which had piratically plundered a number of Scotch

merchant vessels. Barton with his squadrons captured or sunk most of the

Dutch fleet and executed such summary vengeance on the piratical knaves,

as forced a degree of respect for the Scottish flag on all the maritime

powers of Europe. Barton's last and most disastrous fight was one which

was undertaken at the close of a private campaign in search of booty.

He, in company with the rest of his family, had fitted out some

privates, and proceeded against the Portuguese merchantmen. But the laws

which governed the regularity or irregularity of ocean warfare were not

very clearly established and that which held sway was—

"The good old rule—the simple plan

That they should take who had the

power,

And they should keep who can."

So canny Andrew and his men

did not scruple much when a rich English merchantman sailed in their way

to overhaul it, and take possession of a share, at least, of its

freight. Scotland and England for the time being were at peace, and the

complaints of the merchantmen at their losses were hardly deemed of

sufficient importance to form a caslis belis. But the Earl of Surrey

fitted out two ships, which he placed under the command of his two sons,

Lord Thomas and Sir Edward Howard, and sent them in search of the

redoubtable Sir Andrew. Their chase was a short one, for in the Downs

they sighted Barton's ship, "The Lion," and a small pinnace. The two

English war vessels fell on the Scotch ships, and although the latter

were unequally matched the fight was obstinate and prolonged. Sir Andrew

was mortally wounded in the contest, but even when his life blood was

ebbing away on the deck he encouraged his men to keep up the fight by

speaking of St. Andrew's cross. Finally a cannon ball struck him in the

body and he soon after died. Then the English seamen boarded "The Lion,"

and taking advantage of the momentary grief and confusion of the Scots

at the loss of their captain, secured possession of the ship. Sir

Andrew's last words are thus plaintively recorded in the old ballad:

Fight on, my men,' Sir Andrew says,

A little I'm hurt but yet not

slain

But I'll lie down and bleed awhile

And then I'll rise and

fight again.

Fight on, my men,' Sir Andrew says.

'And never flinch before the foe

And stand fast by St. Andrew's

cross

Until you hear my whistle blow.'

* * * *

They never heard his whistle blow

Which made their hearts wax sore

adread."

Many people will hardly know whether to regard Sir Andrew as

a hero or a pirate, and therefore we gladly turn to a more modern

instance to represent the valor of the maritime Scot Abroad. Adam

Duncan, a native of Dundee, entered the British navy as a midshipman in

1746, and in 1761, as captain of the 74-gun ship "Valiant," served under

Admiral Keppel in the expedition against Havanna. In 1789 he was made a

rear-admiral, and in 1793 received the honor of being appointed a

vice-admiral. Holland and France being then at war with Britain and

Russia, Duncan was made commander of the united North Sea fleet of these

latter countries, and his blockade of the Texel was so effective that it

ruined the Dutch trade. In 1797 the Russian fleet having left him, he

gained the greatest victory in his career when he defeated the Dutch

fleet near Camperdown and took Admiral De Winter a prisoner. Duncan was

raised to the peerage as Viscount Duncan, and received a pension of

£2,000. He returned to Scotland and died there in 1804.

Few careers,

whether on land or sea, have been so full of variety, disappointment,

troubles, and triumphs as that of Thomas Cochrane, Earl of Dundonald. He

was born in 1775 and when in his teens was enrolled in the 104th

Regiment. When seventeen years of age he entered the navy and in 1800

was commander of the "Speedy," a 14-gun sloop of war. With it he took in

ten months no fewer than 33 vessels, and in 1801 he captured the ''El

Gamo," a Spanish frigate. In 1804 he became captain of the frigate

"Pallas," and in it made several valuable prizes while cruising off the

Spanish coast. He was constantly engaged in deeds which won him the

admiration of the service, and probably captured more valuable prizes

than any other commander in the British navy at the time. In 1808 he

volunteered to conduct the defence of Fort Trinidad on the Catalonian

coast, and with only 80 men he defeated 1,000 Spaniards in an attack

they made on the castle. Then, after twelve days' persistent fighting

against vastly superior numbers, he blew the place up and returned to

his ship. In 1809 the Admiralty ordered him to try and burn the French

fleet then lying at anchor blockaded in the Basque Roads, and he went on

board a fire-ship containing 1,500 barrels of gunpowder and accompushed

his mission with complete success. Civic honors now flowed upon him and

on returning to Britain he was knighted and elected M. P. for

Westminster. His civic career was not a success owing to his out-spokenness

and ignorance of the ways and wiles of the world. He accused one of his

superiors in the navy, Lord Gambier, of incompetency. There seems to be

no doubt that his charges were perfectly true, but he could not fully

substantiate them, and after a very partial trial Lord Gambier was

acquitted. His lordship's influence, however, told severely against

Cochrane and not only prevented his advancement in the navy but impaired

his influence and social standing. In 1814 he was accused, very

wrongfully, of having taken part in some fraudulent stock jobbing