THERE is no more striking illustration of the perfect

continuity between things new and old in the establishment of the Feudal

System than is to be found in the earliest extant feudal Charters conferring

grants of land. In Scotland they begin with the Eleventh Century. For an

excellent reason those who have written about them are obliged to begin with

at least one much older document. In the end of the Sixth Century Columba,

coming from far Iona, seems to have established a Religious House among the

north-eastern Picts in that district of Scotland between the Dee and the

Spey which was called Buchan. There for several hundred years the little

Abbey of Deer continued to carry on the succession of the Old Columbite

Church. Somewhere about the close of the Ninth Century, after the union of

the Picts and Scots, one of the Monks of this Abbey employed his time and

his skill, as so many of his brethren did all over the Christian world, in

making an embellished copy of the Gospels on fair vellum. It seems to have

been kept in the Monastery as one of its treasures, because nearly two

hundred years later than this Latin writing, another Monk could find no more

safe and lasting method of recording the benefactions of their ancient

House, and the titles by which they held their lands, than by writing the

history of them on the broad margins, and on the vacant half-pages, of this

old manuscript of the Gospels. This, accordingly, he did in the Celtic

tongue, which appears to have been a spoken language in Buchan down to a

much later date. Tradition is perhaps nowhere safer than when it is

transmitted through the quiet memories of the Cloister, and when these are

not distorted by the atmosphere of religious marvel. On secular affairs such

memoranda of the donations and grants of Kings and Chiefs, appear to have

been accepted in the earlier Middle Ages as the truest evidence to be had

respecting the promises of the dead and the obligations of the living. And

so it comes to pass that the Celtic jottings in this old Book of Deir

acquaint us with a long succession of grants of land made by Celtic "Mormaers"

and "Toisechs" to the Abbey during several Centuries, when written Charters

were unknown. It is the old story. Lands expressly including "both mountain

and field," were given, in exclusive possession, to the Columbite Brethren,

sometimes simply named, sometimes still more simply described by childlike

indications such as these—"as far as the Birch tree is between the two Alterins." But one essential feature of the gift or grant always is, that

the land is to be free from the old Celtic Feudalism—the "exactions" of

Mormaer and of Toiseach.

It is impossible to understand the early

Charters —their true place in history, in usage, and in law— without

reference to those much earlier transactions which had been going on for

more than 500 years. Under these, land had been conveyed by and to the same

ranks and conditions of men—from the same motives—in exercise of the same

powers—and with the same promises and effects. There was no change whatever,

except that earliest step in civilisation which comes with the more familiar

knowledge of the art of writing, and which substitutes the sure evidence of

documents that can be read, for the memories of intention transmitted only

through the ear, and recorded only by the breath. That there was no

consciousness of any novelty as regarded the nature of the transaction in

the minds of those who gave the first Charters in Scotland, is clear from

the very form and nature of the Instruments themselves. For in this lies the

full explanation of one great peculiarity about them which has often been

observed, but the true significance of which has not been always as clearly

seen. This peculiarity, is the extreme shortness and simplicity of the

earlier Charters. For brevity and conciseness they have been always the

wonder and admiration of modern lawyers. But the cause and the meaning of

their shortness and simplicity have too much escaped attention. If they had

purported to give or to secure anything which had not been well known

before, this striking brevity would have been impossible. If they had

conveyed new rights and imposed new duties, it would have been necessary, to

describe these, and to explain them. But as they neither did nor professed

to do anything of the sort—as they were nothing more than a new Form of

acknowledgment and security for ancient rights which had been familiar in

the actual transactions of life for centuries before—it was not necessary to

explain anything. Dominion over, and exclusive possession of, property in

land, with all its incidents, had been vested in Kings and Chiefs, and in

others under them, in Scotland, as in all other countries, time out of mind.

Hence, the earliest feudal Charters could be, and were, actually confined to

a few lines on parchment, expressing nothing but the promise and the faith

of those who had the actual power to grant, and the name and designation of

those who were in a position to accept, all the well-known powers and

obligations of Ownership in land.

A very clear proof of the great

antiquity of all these possessory rights and powers comes out in the result

of a formal inquiry or "inquest" held in the year 1116 respecting the landed

property of the ancient See of Glasgow founded by St. Kentigeru in the

Seventh Century. That property, as ascertained upon oath before C good men

of the country," who conducted the inquest, must have consisted in grants

and donations to the first Bishop and his early followers which were then

nearly 500 years old. Yet the evidence was so consecutive and conclusive,

that the verdict was accepted by numerous and powerful men who had the

strongest personal interest in testing it to the last. Possession followed

upon it. And this possession did not consist in mere Tithes or in mere

Church-dues, but in broad lands, and numerous Manors scattered all over the

south of Scotland.' It was not the nature of the thing done, but only the

method of recording it that underwent a change in the dawning light of a

rising civilisation. The earliest extant Charter of lands in Scotland is by

King Duncan, son of Malcolm Canmore, and of the Saxon Queen Margaret

(1094-7). It is a grant to a Religious House, the Monks of St. Cuthbert. It

specifies the lands by name, and refers to the "service" due therefrom as

the essence 'of their value. The extent and nature of that service is simply

described as the service previously possessed by a certain Bishop Fodan. All

rents and dues at that time necessarily took principally the form of

"service," and it was the right of receiving "service" from any given lands

that mainly in that age constituted their value. There was no attempt or

need to specify what they were, further than by reference to the continuity

of enjoyment from a former Owner. It is this definite reference to

well-known pre-existing rights that is one of the most striking features of

the early Charters, and it was this alone which made it possible for them to

be so concise. But no general description of these early Charters of the

Eleventh Century can be so striking as the documents themselves. Here,

therefore, I give, in extenso, a literal translation of this oldest of

Scottish Charters :-

CHARTER OF KING DUNCAN TO THE MONKS

OF ST. CUTHBERT. A.D. 1094.

I Dunecan, Son of King Malcolumb, by

hereditary right King of Scotland, have given in alms to Saint Cuthbert and

to his servants, Tiningeham, Aldeham, Scuchale, Cnolle Hatheruuich, and of

Broccesmuthe, all the service which Fodan the Bishop thence had. And these I

give in such quittance, with sac and Soc (Jurisdiction), as ever St.

Cuthbert has had best from those from whom he holds his alms. And this I

have given for myself, and for the soul of my father, for my brothers and

for my wife, and for my children. And because I would that this gift should

be firm to Saint Cuthbert, I have made my brothers join in the grant. But

whosoever would destroy this, or take from the servants of Saint Cuthbert

any thing of it, let him bear the curse of GOD, and of Saint Cuthbert and

mine. AMEN.

Then follow the rude crosses which the greatest laymen of that age could

alone make to indicate their signature—one cross for the King—nine for as

many witnesses, and one for the learned Scribe who wrote the Deed, and who

added across the uncultured but sacred symbols such syllables as

these--"Crux Duncani."

The same general character belongs to all the

Charters given by the Scottish Sovereigns during the Eleventh, Twelfth, and

Thirteenth Centuries— that is, from the death of Malcolm Canmore, in 1093,

to the death of Alexander III., in 1286. Nor must it be supposed that these

things were done in a corner—that they were the individual acts of Kings,

executed without warrant from the universal sentiment of the nation. In the

reign of Davidi. (1124-1153) Charters of land were expressly given with what

may be called in modern language the consent of Parliament or Great Council

of the nation. In the old Celtic "Scotland" proper, which lay north of the

Forth, they had been given in the true Celtic spirit, with the formal assent

and concurrence of the Seven Earls, the Chiefs of the Seven great Provinces

of the North. But in King David's time, when the Southern Provinces had been

added to the Monarchy, they were given "with confirmation of Bishops, Earls

and Barons "—to which is sometimes added "with consent of the clergy and

people."' All ranks and orders were not only familiar with the nature of

such grants in all parts of the Kingdom, but were familiar with nothing else

as the only guarantee of peaceful Ownership. And so, no elaboration was

required. The Clergy were the only lawyers and the only conveyancers. They

wrote concisely, and to the point. Bits of parchment one inch in breadth,

and a very few inches in length, were enough to convey great Earldoms and

Baronies in the days of David i. Eleven lines on a small parchment conferred

the whole of Annandale upon an ancestor of King Robert the Bruce. This

Charter is so typical, and stands so early among those conveying lands—not

to Churches but to laymen—that I give it also in full translation

CHARTER OF ANANDALE TO ROBERT DE BRUS, A.D. 1124-1130.

David by the Grace

of God, King of Scots, to all his Barons and men and friends, French and

English, greeting. Know that I have given and granted to Robert de Brus,

Estrahanent, and all the land from the march of Dunegal of Stranit, even to

the march of Randulph Meschin. And I will and grant that he hold and have

that land and its castle, well and honourably, with all its customs, to wit,

with whatever customs Randulph Meschin had in Carduill and in his land of

Cumberland, on wtiatever day he had them best and most freely. Witnesses.

It will be observed that in this Charter there is not one word of definition

except by explicit reference to previous well-known and established rights.

The lands are described by marches which are assumed to admit of no dispute.

But all "customs" or services are simply referred to as those which a former

Proprietor had enjoyed, at whatever time and under whatever circumstances he

had them "best and most freely." No feudal service whatever is provided for

in the Charter. Probably this also was left to usage and to the general

duties of allegiance.

These earliest, and almost archaic forms of Charter

are of the highest interest and importance, because, rude and simple as they

are, they contain not only the germs, but the main provisions, and even some

of the very words out of which the latest and most elaborate Charters were

naturally evolved. First it was their object simply to record; and then,

secondly, it became of necessity their object to define. It is impossible to

record clearly anything which cannot be defined distinctly. But nothing can

be defined distinctly respecting which our own conceptions are vague and

hazy, or which is in itself variable—in the sense of depending wholly on

arbitrary Will. Hence it was that in the very nature of things Charters

tended to the abolition of the old lawless exactions of Celtic Feudalism.

They effected this as regards all lands given to the Church by expressly

forbidding these exactions altogether. They effected the same object as

regards lands granted to laymen by substituting definite and fixed amounts

of payment or of service.

But the same necessity for deliberate thought

which is one of the great causes, and at the same time one of the great

consequences of civilisation, called for another definition in the Charters.

What was it that they gave? What, and how much were they intended to secure?

When no technical phrases had been yet established, how was property in land

to be described? The very simple and childlike expedient of describing the

things given as the same with those previously enjoyed by the last Owner,

and of adding by way of emphasis that this equality was to be maintained up

to the highest level of that enjoyment at its best and fullest—this

expedient obviously could not be lasting. It is indeed very curious how long

it did survive in various forms of expression, which are easily recognised

as relics of the infantile conception which we have seen expressed in the

two Charters already given. But the needful definition soon began to grow.

It was purely an instinctive and not at all a formal or scientific process.

It came in the simple effort to record what was meant by the great Manors

and Lordships as well as the smaller estates which had been enjoyed for

centuries. Did they mean nothing but the possession of some small area of

ground which had been roughly inclosed and brought into cultivation? Did all

the rest of the land, which in those early days must have been by far the

greater part of the country—wild ground, hogs, woods, natural opens of rough

grass, hills, mountains—did all these great areas of country belong to

everybody in general and to nobody in particular? Did the fact that these

spaces were used—in the only way in which they could be used —as pasture for

the cattle and sheep of Bondmen and of followers, and of retainers—of all in

fact who lived upon or near the land—did this scattered and indefinite use

prevent, preclude or limit the full Ownership of the Chief, or Lord, or

Owner? Had any great break or change occurred since the' old centuries when

the Celtic Book of Deir had recorded that grants of land included "both

Mountain and Field"? Not at all as definite legal problems to be solved, or

as questions even consciously propounded, but as a necessity of thought in

the mere act of recording that which Charters were intended to convey, these

alternative conceptions would be naturally and inevitably encountered.

Accordingly when we look into the Charters the growth of definite ideas, and

of definite expressions, is most curious and instructive. In the first

extant Charter from King Duncan, as we have seen, there is nothing whatever

to express Possession except the words, "have given in alms" the lands whose

names follow—with the explanation added," all the service" which a preceding

Owner "thence had." The second Charter to Robert de Brus amplifies these

expressions a little. Here it is "all the land" within certain known

boundaries which is "given and granted," with a further explanation that it

is to be "held and had" with its Castle and "all its customs" as held by a

predecessor. This is a step in advance, because "all the land" is clearly

intended to cover the whole area whether cultivated or waste. But a few

years later than King Duncan's Charter, in the reign of King Edgar

(1097-1107) we have another Charter even shorter than the first, but in

which we see still further progress in explicit definition. It is a grant to

the same religious Brotherhood which was specially favoured by the

descendants of Queen Margaret, the Monks of St. Cuthbert. Here the words are

fuller, although still marvellously concise. The estate is designated by its

name, with these words following: "both in lands and in waters, and with all

that is adjacent to it—_namely, that land which lies between Horverdene and

Cnapdene—to have and to hold freely and quietly, and to be disposed of at

the will of the Monks of St. Cuthbert."

The absence of formality—the

perfect simplicity with which these expressions are used, indicate clearly

that they were nothing more than a mere putting into words of the common

understanding of the age, respecting all that was carried in a gift of

lands. In this case the waters appertaining to the land are mentioned

incidentally as included in the gift. And so in yet another Charter of the

same Reign, which is the shortest of all, we have one item specified— which

speedily disappeared for ever—namely, the "men" or Bondmen who were resident

on the property conveyed.' The words are, "with men, with lands, and

waters." And then in another Charter we have light cast—through the same

little lattice- windows of expression—on those most interesting of all

points connected with the history of the occupation and improvement of

land—namely, the condition of the Bondmen, and the conditions under which

the reclamation of wilds and wastes was then deliberately undertaken. In

this document' the King adds these words:-" I have also given to the Monks

twenty-four beasts for reclaiming the same land," and goes on further to

explain that by express agreement with the "men" of a certain district he

had ordained that they should pay to the Monks half a silver merk yearly for

every plough. This is clearly a case of commuted service. If it refers to

Bondmen it shows how light that bondage had become when they were consulted

and made parties to the arrangement. If they were Freemen it shows the

permeating effect of Charters in substituting fixed payments for old but

arbitrary exactions.

As we come down in time, during the reign of David

I., there is a rapid development of form, and of expression, especially when

that Sovereign had to deal with the great Religious Houses of Melros, Kelso,

and Holyrood. Probably among the Monks in those parts of the Low Country

there were writers of greater skill. There is nothing, however, in those

Charters which indicates any novelty whatever in the benefits conferred. On

the contrary, there are the same allusions to previous Owners, and to

accustomed powers. But there is a steady growth in the direction of greater

precision, and of a more complete enumeration of the rights which were

universally understood to be involved in Ownership. Some of these depended

on local position, such as rights over the wrecks of ships. Fishings assume

from the beginning a very definite place, showing how highly they were

valued as an appurtenance of certain estates. Moreover, these are often

conveyed in limited shares sometimes upon distant streams, and restricted to

the sweep of a fixed number of nets. But in these Charters we see the

ordinary and standing definition of that which was specially conveyed in

grants of land, assuming substantially the form which it retained for

centuries. That form arose naturally and necessarily out of the endeavour to

enumerate as exhaustively as possible all the kinds and qualities of surface

which the land presented almost everywhere in those ages. Thus the Charter

of Melros specifies lands to mean "the whole land in wood and plain, in

meadows, and in waters, in pastures and moors, in ways and paths, and in all

other things."'

It must always be remembered that the way in which land is

used, in respect to agriculture, is a totally different matter from the

principle on which land is held, in respect to Ownership. The method of use

is one thing; the principle or the condition of tenure is quite another

thing. It is a great confusion of thought to confound these two together.

Traces and records and survivals in abundance, show that great areas of

country were once used by many men in common, and from this it is con-

eluded that the Ownership could not have belonged to an individual. But this

is altogether erroneous. If the Ownership in the fullest sense had not

belonged to individuals in those days, the men who enjoyed the common use of

it would not have been allowed to enjoy it long. There were plenty others

ready to seize it at a moment's notice, if it were not protected by the

powerful Chief or Baron who had the interest of exclusive Ownership to

assert and to defend. Just as the Crown promised its protection to him as

Owner, so he, and he alone, could afford protection to his men as Users. But

the promiscuous use of such lands amongst his Tenants and retainers was a

necessity arising out of the nature of things. Wild wastes, and woods and

moors, could only be used by and for a number of men, although the Ownership

lay in one. Such surfaces were then useless except for pasture or the chase,

and as they were without fences or divisions of any kind, separate areas

could not be kept for the cattle of separate individuals. In this sense, but

in this sense only, they were used in common. But they were so used only by

individualised groups of men, whether bond or free, whose tenure was

dependent on the tenure of the Lord to whom by Charter it had been given, or

in whose hands still more ancient rights of Ownership had by Charter been

recognised and confirmed. It was always to him that the native population (nativi)

whom he found, or the colonists (coloni) whom he brought, or the Free

Tenants whom he invited, owed even one moment's security and peace. The

enjoyment which, under him, was common to the Few, was an enjoyment

absolutely exclusive of the Many. And the Many were always quite near enough

to make them a continual presence in the mind. From across some rough hill,

or over some dreary moor, or from beyond some firth or bay of the sea,

outsiders, representative of the Many, were always ready to rush in upon the

Few who were protected in the exclusive enjoyment of good natural meadows,

or of sheltered woods with fine pastoral glades, stocked with sheep, and

swine, and cattle. Nothing but the quieting effect of acknowledged power and

right, founded on the deeds and on the authority of centuries, could then

keep the country in peace, or give time and place for the settlements and

improvements of civilisation. Hence the recording work of Charters would

have been indeed imperfect if it had not carefully included all the lands

which, so far as the plough was concerned, were then wastes and

wildernesses, within the area of individual Ownership, for responsibility

and defence. It is not too much to say, that if the thoughtless sentiment

which is now so often cherished in favour of the common use of land, as

distinguished from individual Ownership, had been a sentiment capable of

existing in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, Scotland, which was largely

desert then, would have been nearly as desert at the present day.

Perhaps

it may occur to some, as a distinction, that the Charters I have quoted had

all of them reference to parts of the country which are now Lowland, and

were settled by the Teutonic races. But this is to pre-date a condition of

things which had not then arisen. We have already seen how completely the

Highlands proper had been penetrated, through and through, by the power and

leadership of those races. We have seen, too, how Feudalism in its very

roughest and rudest forms had been long established as the very root and

essence of the ties which bound together the Celtic Chiefs and Clans. But in

addition to all this we have to remember that in the Eleventh and Twelfth

Centuries a great part of Scotland, which was gradually becoming

predominantly Teutonic, was still at that time full of Celts, and that the

early Charters recorded nothing that had not been long habitually known to

them. We have seen that the Book of Deir, written in Buchan in the Twelfth

Century, recorded the transactions of many centuries in the Celtic tongue.

We hear that when Malcolm Canmore visited the plains or low country of Moray

he had to translate the speech of the people to his Saxon Queen. Gaelic

seems to have been certainly understood in Aberdeen and Banff so late as the

beginning of the Twelfth Century. The whole of the south-west of Scotland,

from the Clyde to the Solway, the Province of Galloway, was in those

centuries mainly Celtic, and the Charters of King David are often specially

addressed to "Galwegians," as well as to French (Normans) and Angles. Down

even to the close of the Seventeenth or the beginning of the Eighteenth

Century we are told on good authority that even in the County of Fife so

many of the poorer classes still used only the Gaelic language that it was

an impediment in the employment of them south of the Forth. It is clear,

therefore, that in no part of Scotland, and to no one of its component

races, were the powers and gifts conveyed by Charter anything but a new form

of record for old and familiar facts.

On this point, however, we have one

confirmatory circumstance which, if any were needed, would alone have the

highest value. I have already referred to the fact that for one hundred

years before the Anglo-Normans invaded Celtic Ireland, the native Chiefs and

Kings had begun to give grants of land conveyed in the definite form of

Charter. In the Latin Charter given by the Irish King of Leinster to the

Monastery of Duisk we find fairly begun the same method of enumerating the

things and powers conveyed in the possession of land which we have seen also

beginning in the corresponding Instruments in Scotland. It was a method of

enumeration which became amplified from time to time so as to include

complete possession of everything upon, the land which had come to be known

as of any value in the use or enjoyment of it. This shows that among the

native Celts of Ireland there was nothing new or strange in such kind and

such measure of possession. The Irish Charter of the (approximate) date of

1160 gives the definition or enumeration in two separate forms. First, the

lands are mentioned by name, and then these words are added, "with all their

pertinents in waters, in pastures, in woods"—to which, again, are added in

another line, referring to another portion, "with all its former pertinents,

in rivers and in meadows and in groves." The second of the only two Latin

Charters which remain to us from Irish native Kings, and which is from the

King of Limerick, of about nine years' later date (1169), shows a further

development of the same kind of enumeration,—for it adds to the other words

already quoted these further,—"in fishings and in mills."' Both of these are

in the highest degree significant of the individual appropriations connected

with land, which in actual life and fact had come to be of use and wont

among the Celts of Ireland. If vague Tribal rights had survived in anything,

we might have expected to find them in respect to fishings and in respect to

Mills—both of which were great sources of wealth in those early days, and

one of which— Mills— enabled the proprietor to levy heavy dues on all the

cereal produce of large districts of country.

Returning to the progress of

Charters in Scotland, there is an interesting difference to be observed

between two Charters, both given to ancestors of King Robert the Bruce. I

have already quoted one of extreme brevity and simplicity of form, given by

David r. to Robert de Brus, of certain lands previously held by a certain

Randuiph Meschin. But the same Sovereign gave to the same favourite Knight

another more important Charter of the whole of Annandale to be held in

Forest. This Charter also is so short and simple as to be interesting in the

same point of view—as the mere record of transactions which in themselves

were evidently so familiar as to need no elaborate explanation. It runs thus

"David King of Scots to all good men of his whole land, French and

English and Galwegians, greeting. Know that I have given and granted to

Robert de Brus in fee and heritage, to him and his Heir, the Valley of Anan,

in forest, on both sides of the river of Anan as the marches are from the

forest of Selkirk as far as his land extends towards Stradwith and towards

Clyde, freely and quietly as any other forest of his is best and most freely

held. Wherefore I forbid that any one hunt in the aforesaid forest unless by

his authority on pain of forfeiture of ten pounds, or that any one go

through the aforesaid forest unless by a straight road appointed."'

(Witnesses.)

But some fifty years later, in the reign of William the Lion

(1165-1214), the grandson of this elder Robert de Brus, obtained from that

Sovereign a new Charter of Confirmation for the lands of Annandale, and this

second Charter shows a very considerable advance in legal elaboration.

Still, we see that it is elaboration of form and nothing more. It is a mere

fuller explanation of all that had been meant and implied before. The

enumeration is more explicit. The lands are granted "in wood and plain, in

meadows and pastures, in moors and marshes, in waters, stanks and mills, in

forests and trysts (markets), in hills and harbours, in ways and paths, in

fishings and in all other its just appurtenances, as freely, quietly, fully,

and honorably as ever his father or he himself most freely, quietly, fully,

and honorably held that land of King David my grandfather, or of King

Malcolm my brother—excepting the royal rights which belong to my Royalty, to

wit, Treasure-trove," etc. And all this was to be held for military service,

expressly limited to ten knights, and with special abolition of a burden or

exaction which had evidently been customary before—namely, that of" warding"

the Royal Castles in the district.

In this Charter we have very nearly in

full development all the essential features of grants of land throughout the

Middle Ages. They were not all identical in their terms, because the scope

and intention of such Instruments were not always the same. But the

variations were just of the kind to show that in every case the forms of

expression were not merely conventional, but were measured by the different

meanings of the Donor in each case. Thus there were Charters which conveyed

rights of grazing only, and not of the soil in Ownership. Again, there were

grants of grazing without the grants of game, and vice versa, there were

grants of game and forest with express reservation of the rights of grazing,

which are given separately and to different men. Some of these old records

afford us curious glimpses of the condition of the country and of the habits

and manners of the time. Thus the Avenels, Lords of Eskdale, had a quarrel

with the Monks of Meiros, arising out of the fact that to the Monks they had

given by Charter rights of occupation for agriculture and for grazing in a

forest over which the Avenels had kept only the exclusive privilege of the

chase. The quarrel is composed by a fresh agreement before King Alexander

ii. (12141249), whose edict or award goes into great detail— forbids the

Avenels to keep any domestic animals on the lands, or in the pursuit of game

to break down fences or injure standing corn or cattle. On the other hand

the Monks are to leave all Hart and Roe, Wild Boar, etc., and other game to

the Superior, whilst a curious clause reveals the value then attached to the

sources whence Hawks could be got for the favourite pastime of hawking.The

Monks were not to cut down any tree on which Hawks had nests, nor were they

to cut any such tree until the intention of the Hawks had been clearly

ascertained, that they would not return in the year following. This clause

included not only Falcons, but Sparrow-hawks.

This document is of some

interest in several ways. More than one of our historians have observed that

we hear no complaint in Scotland of any special Forest laws, such as

constituted so great a grievance in England during the early Norman Kings.

And this is true. There were no such savage penalties attached to the

killing of Deer—nor is there any notice of districts of country once settled

and then cleared for the purposes of Forest. In this document we see that

without any special legislation, but only as a natural and usual incident of

property in districts which were naturally covered with woods and real

forests, the chase was valued as a pursuit, and game as a means of

sustenance, and that special bargains were made in regard to it. On the

other hand, we see that it was considered reasonable that mere leases or

grants of game should not interfere with the increase of tillage or the

necessary enclosure of land for cultivation. This is made still more

strikingly apparent by a Charter given to the Abbey of Melros by Walter the

Steward of Scotland in the Reign of Alexander ii., in respect to their

powers of pasturage and of improvement in the Forest of Ayr. In this

document it is especially explained and declared that the Forest rights

retained by the Superior were not to limit or restrict the Abbey in respect

to the number of cattle they might find it possible to support upon the

land, nor in respect to the arable cultivation of any part of them.

But

the greatest interest of all attaching to these documents is the evidence

they afford of the tendency of all Charters and of all written agreements in

that age to make the rights of parties clear, fixed, and definite. It is

impossible to exaggerate the importance of this element at that time—all the

more because the forms in which it appears are not mere technical forms or

the work of skilled lawyers. They are of extreme simplicity, but at the same

time of extreme directness. The detail about the Hawks' nests may seem

childish to us now. But nothing could better illustrate the spirit in which

the respective parties were to act towards each other in the exercise of

rights which might conflict. And be it observed, all this was the mere

interpretation of a contract which the Avenels had voluntarily entered into

by a Charter with the Abbey, so that the edict of the King was not in the

nature of a law, but in the nature of a judgment or decision. But it was a

decision governed by the great principle which is at the root of all

civilised jurisprudence that men must be kept to the fulfilment of their

engagements, and that in the interpretation of these, both rights and

obligations must be at once strictly, and at the same time equitably,

construed.

This was a great period in the history of Scotland —the whole

of this Thirteenth Century to the death of Alexander III., the last of the

direct descendants -of Malcolm Canmore and Queen Margaret—the last of our

Kings who represented the old Celtic Monarchy in the male line. It was a

manly, and a simple time—how manly, was soon to be evinced in the great

struggle with the two Edwards of England—how simple, is evinced by all of

the few documents of the time which have survived, and by the incidental

circumstances which so often come out in them. And in nothing was it nobler,

or more fruitful in good to come, than in this instinctive desire to record,

and to fix, and to place under the highest sanctions, human and divine, all

the old notions of right and wrong—all the old traditions of inherited

authority and of recognised possession, which had been growing up for

centuries, which had become the basis of society, and which needed only to

be consciously recognised, and duly embodied in Instruments of legal force.

It seems strange and almost incongruous to us, but it did not seem at all

incongruous to those old Kings, that they should take a personal part in the

minutest detail of this great process of record and of organisation. In

their own persons—on foot or on horseback—it was common for them to fix the

boundaries of the lands they gave to the Church, by going round the marches,

and once across the area thus defined. It takes us back pleasantly to those

early days when we read King David saying to the Monks of Melros that he

assures to them certain lands "as I myself, and Henry my son, and the Abbot

Richard of the same church, have gone through, and gone round them, on

Friday the morrow of the ascension of our Lord, the second year, to wit,

after that Stephen King of England was taken,"' And this personal

perambulation of the marches is in several cases recorded in the Charters.

Causes were heard by the King in person; and in the dispute so equitably

settled between the Lords of Eskdale and the Monks of that famous Abbey,

which was so dear to, and so favoured by the Kings of that dynasty, we can

well imagine the mixture of grave and gay—the sense of equity and the sense

of fun—with which Alexander ii. must have directed the compromise about the

manifest intentions of Falcons and of Sparrow- hawks, in leaving or in

keeping to their old nesting trees.

It was in the midst of this rapid

process of record, and of consolidation, and of progress, that Scotland

suffered the most terrible calamities that can befall a nation—the

extinction of an honoured Dynasty,—a disputed succession,—desolating

invasions from a foreign army,—and lastly, a long and desperate struggle for

national independence. Counting from the death of Alexander iii. to the

Battle of Bannockburn, this unsettled and bloody time lasted for

twenty-eight years, and if we count to the final Treaty acknowledging the

Independence of Scotland, it lasted forty-two years—from 1286 to 1328. As a

matter of course there were immense changes made in the holders of landed

property in consequence of the contest. Barons, and Knights, and Chiefs who

in the dif- ferent divisions, and among the still differing races of the

Monarchy, had been loyal to the cause of national unity and

independence—these had to be rewarded. Those, on the other hand, who were

disloyal to that cause, had to take the consequences of their defeat. It is

not too much to say that a very large part of the land of Scotland changed

hands, whilst another large part remained indeed in the same families in

which it had been for centuries, but was entered for the first time in the

great Charter Roll, which recorded under a new and a glorious sanction the

ancient inheritances which had been won by services too old and too

continuous to be recorded, but which perhaps had been not less important to

an earlier condition of society.

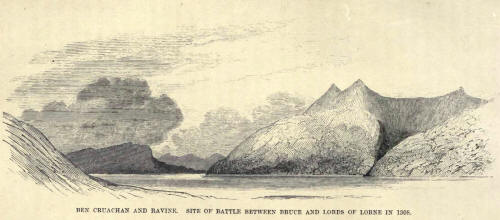

This comes out very clearly in the earliest extant Charters connected with

my own family. King Robert the Bruce was not likely to forget the loyal

Knight of Lochow who had been his close companion throughout his memorable

adventures between 1306 when he assumed the Crown, and the great battle in

which he vindicated that assumption before the world. The King had good

reason to remember Lochow. It was in the precipitous pass at the foot of Ben

Cruachan, where that fine mountain falls into the gorge through which the

Lake finds its outlet to the Sea, that he had one of the fiercest and most

dangerous contests of the war. The Island and Western Clans under the Celtic

Chiefs, descended from Somerled, had with their characteristic traditions

from the Sea, occupied the Lake' with galleys, and the steep slopes of

Cruachan with men. Nothing but personal- strength and courage, seconded by

the only strategy which such ground admitted of, brought the little band of

Bruce victoriously through that encounter; and so desperate was it at one

moment, that the King was as nearly as possible overpowered,—his plaid was

torn from his person—the brooch by which it was fastened was carried off,

and remains to this day in the possession of the gallant Chief of the Clan

Macdougall in the Castle of Dunolly. It was not, however, till after the

death of his brave companion in arms, Sir Niel Campbell, who did not long

survive the Battle of Bannockburn, dying in 1315, that the family seems to

have cared to have that new form of title which consisted in a bit of

parchment. The King had given to Sir Niel his own sister, Lady Mary, in

marriage, and although the young Knight who succeeded to the Barony of

Lochow was not his own nephew, he was the eldest son of his old friend, and

the stepson of his sister. Probably it was a pleasure to the King, almost as

much as a favour to this brave and impetuous youth, to give a writing under

his own hand, "confirming" those ancient possessions in the West which had

been so long held, and so bravely risked in his cause. In this case the

words must have been more than form which were addressed by "Robert, by the

grace of God, King of the Scots, to all good men of his whole land,

greeting; "on behalf of his beloved and faithful Cohn, son of Niel Cambel,

Knight"—confirming to him "the whole land of Lochow, in one free Barony, by

all its righteous metes and marches, in wood and plain, meadows and

pastures, muirs and marshes, petaries, ways, paths, and waters, stanks,

fish-ponds, and mills, and with the patronage of the churches, in buntings

and hawkings, and in all its other liberties, privileges, and just

pertinents, as well named, as not named."

But beyond necessary inference,

the simple brevity of these old Charters leaves much to be understood, and

it is sometimes only by pure accident and by incidental allusions in later

Instruments that we find out how purely they were very often Instruments of

mere record and recognition in respect to facts, to rights, and to powers

which were then of very ancient standing. This comes out very strikingly in

a later Charter granted by David ii., son and successor of Robert the Bruce,

to another member of the Cambel family in 1368. In this document we have an

express reference to rights which had been acquired by the Celtic Chiefs,

under their own system, and by their own pre-eminence among their own

people: for this Charter confirms and secures to Gillespie (Archibald)

Cambel "all the liberties and customs" which had belonged to a progenitor,

who is designated by his Celtic patronymic of Duncan Mac Duine. Now this

Duncan appears to have flourished about 150 years earlier, in the reign of

Alexander ii., and he is expressly referred to as having been then already

in possession of all the "liberties and customs" of the Barony of Lochow, as

well as of others not specified. But this is not all— it is not even the

most significant part of the reference. For in the use, in a formal Charter,

of the name "Mac Duine," we have clear historic evidence of the truth of

much older traditions. We are carried back to times when this patronymic of

Mac Duine must have arisen among the Dairiadic Celts (who were a conquering

and colonising colony from the "Scots" of Ireland) in the period between the

Fifth and the Seventh Centuries.

From the War of Independence and the

death of King Robert the Bruce, in 1329, we are in the full light of

history, and are in possession of an uninterrupted series of Charters for

the space of 500 years down to our own time. There is a perfect continuity

of character, and a complete universality of application to every part and

Province of the Kingdom. There was no distinction whatever between the

Lowlands and the Highlands. The only Celtic race which in the Fourteenth

Century was still noticed as representing a separate portion of the Kingdom,

was the Gaiwegians—the people of the south-western country of Galloway. The

Gaelic population of the Highlands were not only included in the "Scots,"

but were the first owners of the name. The earliest and the most despotic of

all the forms of native Feudalism had been developed and had long been

firmly established among them. Even the more civilised form of written

Charters had been adopted by the more civilised Lords of the Isles, and the

Mackenzies, Macleans, and Mackintoshes had accepted and submitted to the new

order of things which confirmed, but at the same time regulated their

powers.' Accordingly there is not the smallest difference between the

Charters granted in different parts of the Kingdom from the Tweed to the

Thurso, and from the mountains of Applecross to the headlands of Buchan. And

no wonder—for everywhere almost the Celts had been the original population,

and the very names of the lands disposed of were often as purely Celtic in

the Lowlands as they could be in any part of the Highlands. Many of these

have long ago entirely disappeared, and it is not without surprise that in

many of the earliest Charters of lands in districts which have long been

purely Teutonic, we meet with crowds of names as purely Gaelic as the

existing names in the centre of the counties of Argyll and Inverness.

We

see the same absolute unconsciousness on the part of the Sovereigns that

they were doing or giving anything that was new when they gave grants of

land anywhere—in any and in every portion of their Kingdom. The whole Valley

of Douglas, sixteen miles in length from Tinto to Cairntable, was conveyed

to the good and brave Sir James Douglas by Robert the Bruce in a Charter in

the briefest form. The wild coasts and mountains of Gareloch on the mainland

opposite to Skye had been already disposed of in precisely a similar form by

Bruce's predecessor, Alexander iii., in 1272, to a Celtic Chief, who, again,

had previously held under Charter from the Celtic Earl of Ross. And when, •

little later, Charters became more extended in form, and purported to

specify a little more expressly that which they conveyed, it almost seems as

if all the resources of language were exhausted to enumerate and include

complete rights of possession and disposal, of every kind and degree, over

every kind and description of land embraced within the ancient and

well-known boundaries of the Lordship or of the estate. This came as a

matter of course everywhere, but perhaps in the very nature of things it

would have been less possible even to conceive of any exception as regards

what is called CC land in the Highlands than in the Lowlands. Nowhere,

indeed, in these Islands, have there ever been lands in the state of

"Prairie"—that is to say, great areas of virgin soil, unencumbered with

wood, and ready for the plough, without any process of reclamation.

Everywhere in Scotland the largest part of the country was covered with

natural forests, and with dense scrubby woods, which are even more difficult

to clear and to eradicate; whilst elsewhere little but moors and bogs varied

the surface under conditions even more intractable for agricultural

operations. But in the Highlands, if Charters had given nothing under the

full rights of individual Ownership, except the cultivated or even the

cultivable land, there would have been nothing given at all. That which in

England would have gone under the name of waste was practically the whole

surface of the country. Accordingly, in no Instrument of the Middle Ages is

there the smallest consciousness even shown that such distinctions could be

drawn, or that such a question could emerge.

On the other hand there

arose, as I have already shown, an instinctive desire to record and to

specify, and to define, all that by immemorial usage, and the habits and

conditions of life in that age, had been held, used, and enjoyed, as of the

essence of the Ownership of land. "With all its just pertinents" are the

simple words usually added in the earliest Charters to the name of the

property conveyed. And when these "just pertinents" came to be set forth at

length, and separately named, they are always so named, not as novelties,

but expressly as the items of ancient usage. The most elaborate enumeration

I have observed is one contained in a Charter of Confirmation granted by

King Robert the Bruce to Malcolm Earl of Lennox, and dated July 141 1321.1

But this Malcolm was the fourth Earl who had been then in possession of that

great Earldom, the larger part of which was at that time purely Celtic, and

the Charter, as usual, refers to it and to its "just pertinents," as enjoyed

from a former age. Theenumeration is only remarkable as containing such

curious expressions as "infangandthefe and outfangandthefe," and as

including such details as the "Eyries of Birds," along with the more

substantial advantages then arising from the escheats and fines attaching to

feudal dues and to the Baronial Courts in the exercise of criminal

jurisdiction. To the subject of the Courts of Heritable Jurisdiction I shall

return in a later Chapter, only observing here that in this as in other

things the early Charters were only granting under definite and legal

sanction the irregular but very ancient powers of jurisdiction which were

inseparable from the immense and supreme authority exercised by early Chiefs

and Leaders among all the Aryan races.

There is, indeed, one remarkable

addition to the list of enumerated items, which appears to have been first

inserted in the later years of King Robert the Bruce. That addition consists

in such words as these (for there is some variation), with its tenants and

tenandries, and service of free tenants," to which again are added, in some

cases, such further words as these, "with all the native men of the same,"

that is, the Bondmen. Before the close of the century in which King Robert

the Bruce died, about 1390, this last item dropped out of the account. The

Bondmen had either disappeared, or had become so unimportant as not to be

worth separate mention. On the other hand, "tenandries, tenants, and

services of free tenants," survived through centuries, becoming the regular

conventional phrase under which all the holdings, farms, and revenues of an

estate were included, whether these revenues were derived from sub-feus, or

from leases, or from yearly holdings, or from other forms of tenure which

are now lost or are indistinguishable.

But through all mere developments

of wording, and redundancies of expression, that which is of most interest

in all those Charters is the undying witness which they bear to the one

original idea of abolishing all the old indefinite and arbitrary exactions

of Celtic Feudalism, as it had become established everywhere before the days

of written documents. Certain definite amounts of military service were

commonly provided for in the earlier centuries; but this provision is always

followed by words declaring it to be in full satisfaction and substitution

"for every other service or custom or exaction." Among the instruments

published in The Book of Grant there is one highly illustrative of the fear

which had arisen of demands or dues of this nature which were indefinite. A

certain Knight, Sir Gilbert of Glenkerny, who held his lands by Charter from

the Earldom of Strathearn, had been induced by friendship or political

sympathy to serve personally, and with his following in the wars of the

disputed succession, under Malise, who then held that Earldom. But this

service had not been due under his Charter. In June 1306, therefore, fearing

that his actual service might be construed as having been feudal service, he

procured from the Earl Malise a Deed of acknowledgment as to the true nature

of the assistance he had rendered. In this new Charter Earl Malise formally

declares that neither he nor any of his heirs should ever claim or pretend

that such service should be pleaded as consuetudinary, or should be quoted

as affecting in any way the original conditions of Sir Gilbert's tenure.

But as the great Earldoms and Baronies of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Centuries became broken up into smaller Estates, the practice became general

to commute all military services into fixed amounts of money. It was an

inevitable result of advancing civilisation and of settled government that

the importance of many civil obligations became much more prominent than

those connected with perpetual fighting. Society ceased to think continually

of bows and arrows and of coats of mail. It wished to enjoy life, and not

merely, to defend or to secure it. In connection with this change a new form

of expression and new conditions of tenure came into use. Lands held under

Charter for a fixed annual sum of Feu-duty were said to be given and held

"in Feu-farm"-----that is to say, the tenure was that of Feu, or Fee, but

subject to an annual payment, which came under the old designation of "Ferm"—or

Rent, from the Latin "Firma."' In a very large number of cases, soon

becoming the great majority, the annual payment being measured in a fixed

amount of produce, either became purely nominal, or at least was very small;

whilst still later the fashion set in of making the grants virtually

free—with nothing left of the ancient Servitudes except some Token, often

highly poetic and even sentimental. It was frequently specified that these

Tokens were to be offered at and on the altar of some Church dedicated to a

Patron Saint, or on some one or other of the great festivals of the Catholic

Church. The nature of these Tokens is sometimes very whimsical—such as a few

pounds of wax, or a little cumin. Sometimes they are purely emblematic—as in

the case of an Arrow. Sometimes they breathe that common love of Nature

which ever increases with the advance of civilisation. The presentation of a

red rose is a common Token; whilst in one Charter we have the beautiful

expression of a tender reverence in the reservation of a chaplet of roses,

not red, but white, which was to be presented to the Superior every year on

the Feast of St. John the Baptist.

It may perhaps surprise some persons to

be told that in Scotland at least we are still in "The Age of Charters." Not

only are almost all Estates held on tenures dating back to Charters of the

oldest form, but new Charters are being granted every day which, both in

form and in substance, are the lineal descendants and the living

representatives of the Instruments which were executed eight hundred years

ago. They constitute the favourite tenure of all land acquired for the

purposes of building and of residence. Most of the Towns in Scotland, and

almost all the rich and comfortable villas which spangle the shores and

estuaries of our great rivers, are built upon the tenure conveyed in Feu-Charters.

In these Instruments the continuity of phrases from the earliest times is

remarkable. The ceremonies once necessary for the giving of Possession—the

symbolical acts such as handing over actual bits and portions of the

soil—all these have been abolished—although some of them survived until a

few years ago. But the fundamental principles, and some of the dominant

expressions, are the same. The Proprietor hands over to the new Owner—the

Vassal in ancient and still legal language,—the Feuar in modern parlance—the

designated area of land "in feu-farm, fee, and heritage for ever," for

payment of the Feu-duty, and for performance of the other stipulations which

follow. Next, the Proprietor binds himself to free and relieve his new Feuar

of all feudal dues and casualties which may be payable to the Over-Lord, or

the Superior from whom the ultimate Title may have come—and this "for all

time coming." Lastly—and this is very curious—the Proprietor, who now

becomes only the Superior of the Feuar, binds himself to accept one fixed

payment at some certain definite interval of years, in lieu of all the old

customary feudal fines and "casualties." This fixed payment generally

consists in a double Feu-duty for one year, at intervals of from nineteen to

twenty-five years. The doctrine of the law is that every Feu so granted

constitutes full and free Ownership, and that all restrictions and

restraints upon it must be very clearly and distinctly provided for in the

written words of the Charter. Moreover, there is a presumption against even

express restrictions where these have not been continuously and.

consistently enforced. Some decisions adverse to the enforcement of certain

restrictions on Feuars in particular cases, have been hailed by ignorant

writers as happy limitations upon over-strained rights of Property. But

those decisions have all been, on the contrary, founded on the very opposite

doctrine of the rights of Ownership construed in the very highest sense. It

is the Feuar who has now become the possessor and representative of these

rights: and the doctrine of the Courts is that no restraint upon them can be

allowed which does not rest on the clearest evidence of deliberate contract,

and of acknowledged obligation. In this as in other matters the spirit of

Judicial interpretation in enforcing the strictest rights of property, has

laid the best and the only secure foundation of popular rights. The number

of Feuars has increased enormously. Popular sympathies are with them, and

the Courts of Law, when insisting on the completeness of their Ownership,

subject only to stipulations the most definite and express, have been

insisting on the same principle of unrestricted and undivided Ownership

which also ruled the case of the largest Baronies and Earldoms. Thus the

most ancient presumptions of law which have affected great Estates for many

centuries have equally in our own days established the most popular of all

the tenures of land in Scotland. Not only are feus taken more and more

largely by all ranks and classes, but the Feu-duties which they pay for the

"Fee-farm" are among the most favourite investments for various Charitable

and Public Funds. Thus the fundamental principles of the first written

Feudal Charters have not only lain at the root of the civilisation of

Scotland for 800 years, but have lent themselves without one break in a

perfect continuity to the latest developments of modern life.

It is not

unimportant to remember that the early age of Charters for the tenure of

land was also the early age of Charters for the tenure of Municipal

Privilege. Moreover there is the same clear evidence in this case as in the

other, that the first grants of Municipal Privilege were acts of

confirmation and of record rather than acts of original institution. There

are references to Burghal communities of a much earlier date, and it has

even been contended that in the southern parts of the Kingdom some of them

had survived from Roman times. It is at least certain that through the same

invaluable channel of the Latin Church the memory and the tradition of them

had never been extinguished. When, therefore, the Kings of the Canmore

dynasty gave Charters to some Burghs in the most Anglo-Saxon parts of

Scotland, there are the same express references to older times which in the

case of land Charters refer us back to liberties and possessions which had

been of old. There are indeed some instances in which new Towns or favourite

villages were for the first time erected into Royal Burghs; but the 'date of

existing Charters is no indication in itself of such an origin. Thus in the

case of Dundee, one of the most important of the old Scotch Burghs, the

Charter granted by Robert the Bruce in 1327 was the result of a special

inquiry' which had been instituted by that Sovereign in 1325, into the

rights and liberties of the Burgh in the times of his predecessors on the

throne of Scotland, and these rights and liberties having been ascertained,

were confirmed, and were definitely recorded in the new form of Instrument

which had risen into the highest rank of legal value.

There is, indeed,

connected with this subject, one very curious indication of the tendency of

that age towards the making of clear definitions in respect to rights which

had previously rested on usage only. This indication is afforded in one of

the earliest examples which have come down to us of legislation in Scotland.

It is a short Act passed in the reign of William the Lion, in favour of what

was then called the "freedom" or the "liberty" of Burghs. Popular "freedom"

did not then consist in what we understand by the word now. On the contrary,

a "liberty" then meant always, as applied to Burghs, some exclusive

privilege in the form of a trade- monopoly. It cannot be too often repeated

that the system which we now call Protection was the system on which all our

great trading communities were founded, and in which they were brought up

and nursed. It was not the class 'of landowners, but the class of traders

and mechanics, who invented the close restrictions upon the freedom of

industry which were for centuries considered the very foundation of all

possible prosperity in Burghs. It would, indeed, be more accurate to say

that they were not invented by any one, or by any section of the community,

for they were, like all the other laws of a rising people, in harmony with

the general sentiments and instincts of the time. One of the earliest of

those restrictions was upon free trade in wool and in skins. Even in those

early centuries the trade in wool had become the most valuable of all

domestic industries; and consequently one of the earliest "liberties"

accorded to the Burgesses of chartered Towns was the right of prohibiting

all men but themselves from engaging in this trade within their own

boundaries. And this did not mean the boundaries of their own Town. It meant

the boundaries of some large territory lying round about, which for this

purpose was annexed to the Burgh as the area over which the monopoly was to

prevail. It is in connection with this idea of popular "freedoms" and rights

that we have William the Lion enacting in his Parliament or Great Council of

the nation, about the year 1214, that all the landowners, great and small,

clerical or lay, within those Burghal areas of monopoly should be absolutely

subject to it, to such an extent that they were not to be free to dispose

otherwise of the most valuable produce of their own estates. Nothing could

be more precise than this record and definition of what usage appears to

have established in connection with these Burghal "freedoms." "No Prelate

nor Churchman, Earl, Baron, or secular person, shall presume to buy Wool,

Skins, Hides, or such like merchandise, but that they shall sell the same to

merchants of Burghs within whose shiredom and liberty the owner and seller

of such merchandise does dwell."' In the case of the Burgh of Dundee this

privilege was found by the "trusty and faithful men," to whom the inquiry

was committed by King Robert I., to have extended over the whole "Sheriffdom

of Forfar," and in the new Charter accordingly the same wide boundaries of

monopoly are expressly confirmed.'

In these strange and almost grotesque

provisions of the earliest extant laws and Charters of the Scottish

Monarchy, in favour of Trade monopolies in the hands of Burghs, we have a

very clear refutation of that most vulgar of all historical errors which

attributes the doctrines then legally established to the exclusive and

selfish interests of one particular class, and that class the Owners of

land. We have, indeed, very little knowledge in detail as to how the Great

Councils of the nation were then summoned, or how they were composed in the

reign of William the Lion. In all probability there was but little formality

either as to the one or as to the other. There is not even uniformity in the

few words of preamble with which those short and simple laws were passed.

They are enacted sometimes with consent "of Bishops, Abbots, Earls, Barons,

and Thanes, and all the community of the Kynryk" (kingdom); sometimes, more

shortly, "by counsel of his Kynryk" only—sometimes "by counsel of the

community." But that which we really do know does not depend on these

archaic prefatory forms. It depends on the persistent memory of the Scottish

people that this was the happiest the formative time—in their national

history—the time to which later documents all referred as the highest

fountain of authority and of legal tradition the time when all the races and

all the classes of the growing nation were being moulded into one government

and one people.

The very absence of detailed information as to the manner

in which these old laws were enacted, speaks volumes as to their real nature

and origin. They were the mere outward expression of ideas and opinions

which had long been universally accepted. And crude and rude as we may now

think the provisions for Protection and monopoly in matters of Trade, it is

probable that they did really promote and foster the beginnings of commerce,

and did certainly determine the seat of them in particular localities. That

they did this at the immediate cost of some loss to the owners and farmers

of land is certain. This is proved, and it is all that can be proved, by the

doctrines of Free Trade. Nor is it probable that this cost was wholly

unknown to those classes at the time. The prohibition of direct sale to

foreign merchants indicates clearly enough that if they had not been

prohibited, such foreign merchants would have visited the country, and would

have given higher prices than the merchants of Berwick or Dundee. But the

general sense of all classes seems to have been instinctively in favour of

Protection—on the simple ground that it was assumed to be a national object

to establish and to encourage, even at some cost, native merchants, and

native mercantile communities. Probably this assumption was made without

argument or conscious reasoning of any kind, and almost certainly without

any attempt to calculate what the extra cost might be to the other classes

of society. It is certain, however, that the spirit of monopoly thus planted

in the Burghs was continued and developed in these communities until it

almost stifled the commerce which it aimed at protecting. The Trade-Guilds

became most tyrannically exclusive, and it was not until almost our own time

that the evils attending them became obvious to all.

It was most

fortunate, and in some respects most singular, that no similar spirit, and

no similar legislation, arose in our early history in respect to dealings in

land. The blunder is very gross indeed which confounds property in anything

with monopoly in dealing or exchange. They are not only different, but they

are the antithesis of each other. Monopoly consists in the exclusion or

limitation of Free Exchange. But Free Exchange depends absolutely on Free

Possession. Men cannot exchange with each other freely anything which they

do not possess fully. They cannot give to another that which they do not

hold themselves. Therefore, that recording and defining process, in respect

to the fulness of Ownership, which we have seen to be the basis of all

written Charters, was the essential preliminary and condition of Free

Exchange in respect to land. In acknowledging, and in giving a legal form to

rights of possession which had been long acquired, our early laws made those

rights easily transferable from one man to another. And on such transfers

there was no restriction. The idea of Entails was of much later date. In the

early centuries of the Scottish Monarchy the right of alienation was

recognised as co-extensive with the right of possession. Moreover, this

universal right of alienation corresponded with an equally universal right

of acquisition. It was a right which had no limits as regarded any

particular classes of men, whether distinguished from others by birth, or

(as in the case of traders) by pursuits and avocations. All men who owned

land could dispose of it, not to particular classes only, but to all other

men who could buy it. In this respect the Feudalism of our Island avoided

that element of monopoly which was developed in the Teutonic Feudalism of

Germany. In Prussia, for example, particular areas of land could only be

bought and sold among certain restricted breeds of men. One set of acres

belonged to and could only be held by the Peasant class—another set of acres

belonged to, and could only be held by the class of Nobles. Free exchange in

Land was rendered impossible by these barriers of monopoly, properly so

called. Some years ago ignorant men were calling in this country for some

imitation of the land reforms of the great Prussian ministers Stein and

Hardenberg. They did not know that one main object of those reforms was to

establish in Prussia that very system of full property,

of undivided

Ownership,—and therefore of free exchangeability, which had been established

here for centuries, and was indeed of immemorial antiquity. The German

statesmen were driven by the utter ruin which restrictions on the full and

free Ownership of land were bringing on the country, to aim at and

ultimately to effect the complete abolition of all such restrictions. But

they were brought to see this not without a struggle. They clung for a time

to the artificial Protection of Peasants' land —for the sake of keeping up

the military population. But once they had entered on the path of

enfranchisement they found that they could not halt short of the only

conclusion to which it logically and practically led. The bondage of men to

the soil had to be abandoned, and the correlative bondage of the soil to one

class of men, had to be abandoned also. Two other correlatives had to be

substituted for these: one was—fall and unrestricted Ownership; the other

was the free transfer or saleability of that Ownership to men of all classes

and degrees. All this had been effected in Scotland more than 500 years

before. Bondage to the soil had been killed out with Serfdom. Ownership had

been redeemed from arbitrary exactions—had been made as full and definite,

and undivided, as words could make it. It had been conveyed in forms which

lent themselves to easy transfer, and to the security of a multitude of

subordinate transactions. This was the recording work—in so far as they did

any work at all —of the early Charters. Those who held them immediately

began to alienate, to sell, to sub-feu, to lease, and. in many complicated

forms to dispose of, to other men, that Ownership which is the essential

basis of Free Exchange of every kind and of every name.

There never was in

Scotland any restriction either as regarded the classes of men to whom

Charters were given, or as regards the classes to whom derivative tenures

could be sold or granted. To the Burghs themselves valuable lands were

sometimes granted by these Charters as well as various dues and lordships

over landed property. These constitute to this day, portions of the "Common

Good" of various Burghs, and such estates have been managed by the

respective Corporations on precisely the same principles on which land has

been managed by other Owners.

We must look back then on the Age of the

first Charters as having laid the foundations of national progress on the

firm ground of ancient rights and obligations so clearly and accurately

defined as thereby to be made the subjects of Free Exchange. The exceptional

privileges given to popular Bodies, constituting in their hands exclusive

trade monopolies, were at least accessible to as many as could place

themselves in the position of Burgesses by residence or otherwise. They

were, at all events, in accordance with the national sentiment of the time,

and the Charters under which they were formally secured took their place

among the Institutions which welded together the various classes and

interests of the State.

All of these classes and interests had been taught

and drilled to feel and to act together in and by the War of Independence.

The Clergy had taken an early and an honourable part. A convocation of the

Church, held at Dundee, had been the earliest public Body to espouse the

cause of Bruce. The Towns and Burghs had co-operated in hostility to the

scattered English garrisons. A mere handful of Knights had indeed begun the

war, but each small success had rallied others to the standard, and in so

far as popular sentiment was operative at all in those times, it spread by

contagion among the military classes without distinction of origin or of

race. Almost all parts of the Kingdom sent their contingents to the little

army which won the day at Bannockburn. Of the four Divisions or "Battles"

into which that army was arranged, the one which Bruce himself commanded was

composed of the men of Carrick, of Argyll, and of the Isles. These must have

been almost purely Celtic, yet we hear nothing of the peculiar, impetuous,

but undisciplined and unsteady methods of fighting which afterwards became

so celebrated as characteristic of the Highland Clans. Indeed from the

position assigned to them by the King, round his own person, and held as a

Reserve, it is clear that they must have been considered among the very best

and most highly disciplined troops at his disposal. It would almost seem as

if the military genius of that remarkable man, and the necessities of rigid

discipline which his long and arduous contest imposed upon him, had enabled

him to anticipate these modern days when Highland regiments have been not

only the most dashing, but the steadiest and most enduring among the

battalions of the British army. For, of this amalgamating power exercised by

Bruce, we have another example which is too little remembered. Bannockburn,

as one of the Decisive Battles of the World, has obliterated the memory of

another battle, which, as a feat of arms, was hardly less memorable. It is

almost forgotten now that, eight years after Bannockburn, in 1322, King

Robert invaded England, and again routed Edward ii. in a pitched battle in

his own Kingdom, in the heart of Yorkshire. In this battle of Byland Abbey,

it is recorded that the critical operation of the day, in the carrying of a

steep hill, was committed by Bruce to the same Western and Celtic soldiers

who had been under his own special command at Bannockburn, and to whom, in

the heat of this new day, he had recourse to carry the high and craggy ridge

which looks down on the Yale of Pickering. The nature of this manoeuvre,

executed under the good Lord James Douglas, is specially likened by the

historian to that by which the King had defeated the Chief of Lorne on the

steep sides of Ben Cruachan in 1307.