|

HOW

THE

EMIGRANTS FROM

THE STATES REACHED CANADA -

APPEARANCE

OF THE COUNTRY—THE INDIANS—THE WILD ANIMALS.

As we all

know, a hundred years ago there

were no railway or steamboat lines on

which to travel. Between the Canadian

border and the frontier settlements in

the States stretched two, three and four

hundred

miles of dense forest, inhabited by wandering tribes

of Indians and infested by ferocious wild

animals

in great abundance. It was the practice of the

emigrants from the States to pack all their belongings, or

at least all of them they could take with

them, in

canvas-covered wagons, similar to those used by

gypsies at the present day. In these conveyances they

lived while on their long and dangerous

journey.

Among the "Pennsylvania Dutch" the "Conestoga

wagon" was used; its box was oval or boat

shaped.

This style of wagon has long since become obsolete.

Indeed it was only in general use among these

people.

The wagon was usually drawn by a yoke of oxen, for

horses were not suited for such travel. Many of the early settlers,

however, made the journey on horseback.

There being no public roads

through the forest, the emigrant was obliged to follow Indian trails, the

course of rivers, or "blazes" (marks on the trees), made by some previous

traveller. Later on, after roads had been constructed (the government

frequently sending men out to slash down the trees on the routes surveyed

for the leading roads and clear the way for the wagon track), the

emigrants came with horse teams, four horses being usually attached to a

wagon. As may well be imagined the journey was not only full of danger at

every step, but was also tiresome in the extreme. The women and young

children suffered most, but they courageously encountered all the

hardships of the way to reach the "promised land," where they would be

permitted to live free and peacefully. It was a lonesome and melancholy

sight to watch the wagons slowly wend their way between the logs and

stumps of the newly- cut wagon road on their way to Canada. These journeys

occupied three and four and sometimes eight and ten weeks. The passage

through the unbroken forest, over the mountains and through the passes,

being so slow and tedious, the journey necessarily lasted all the longer.

Usually several, sometimes quite a

number, of families came in company, and thus by mutual help got over

difficulties which otherwise might have been unsurmountable. The emigrants

generally took a cow or two with them to help them begin life in the new

country, as well as to furnish milk and even butter on the way. The milk

in some cases was hung in a leather bag at the back of the wagon, and it

is said that the motion of the wagon would frequently churn it into

butter. Chickens, too, were also taken in numbers, and these supplied them

with welcome eggs, so that the weary emigrants were not obliged to be

without their customary meal of ham and eggs. At the dawn of day, in their

encampment in the woods, could be heard the crowing of chanticleer as he

made the welkin ring in depths of wood with the familiar notes of welcome

to the opening dawn.

The journey from Southern

Pennsylvania led through the Alleghany Mountains. At one point the pass

was so narrow that only one team could go through at a time. When two

teams happened to meet one of the wagons had to be taken apart and carried

past the other on men's shoulders. When they came to streams which could

not be forded, if a scow to cross was not obtainable, trees were quickly

cut down and a raft constructed for conveying them over the stream. As the

stream of emigrants increased, ferries were placed and attended to by

persons living in the vicinity of these crossing -places. Some of the old

ferry boats were flat- bottomed boats propelled by horse-power, the horse

having to walk on a tread-mill, or to walk round and revolve a post which

connected with machinery, and which kept the paddle wheels in motion. The

rope and capstan was also used in the early days for crossing the rivers

and small lakes. The rope, attached to a revolving post on board, was run

out and fastened to a tree or post on shore, or attached to a heavy anchor

and carried forward by a small boat the length of the rope and then

dropped to the bottom. The post on board was then turned by a horse or by

hand power, which caused the boat to be pulled ahead as the rope was

coiled around the capstan.

Another method of propulsion, in

certain places, was by stretching a rope tightly across a stream and

fastening it to a post or tree oil sides. A pole or stem with a roller on

the end stood oil prow of the boat, the boat being pushed out from the

shore. The force of the stream caused the roller to revolve and thus

carried the boat across. Still another form of power was by running the

rope through a hole at each end of the boat and pulling the boat across by

hand. Along the Niagara River, Niagara, Queenston and Fort Eric were the

principal crossing places. Buffalo, a century ago, consisted only of a few

huts. The locality being low and marshy was considered undesirable for

farming purposes.

In coasting or travelling up the

large lakes and rivers large canoes and bateaux, long flat-bottomed boats

with pointed ends, propelled by oars and sails, and in rapids and shallow

places by long poles, were made use of. The Durham and Schenectady boats

used on the St. Lawrence before the days of the steamboat, were only a

form of bateaux. The canoes used for transporting merchandise were quite

large, some of them being four- teen or fifteen feet long and three or

four feet wide. It required four or five men to paddle these canoes when

laden with goods. It was by means of large canoes, also called bateaux,

that the French in the early days of Canada transported their furs and

merchandise from one place to another, in many cases hundreds of miles.

When the streams did not intersect, or falls and rapids occurred, portages

were made at the most convenient places, when the canoes and bateaux and

their cargoes were dragged or carried overland and again launched. If the

portage was a long one, as for instance that between Queenston and

Chippewa, when the traffic became large, the goods were conveyed overland

in wagons, people living in the vicinity of the portage owning a large

number of wagons and doing a lucrative business. The lakes and rivers of

the country formed a waterway which was found very convenient in the early

days when the country was covered with swamp and forest; they formed the

only real public highways. They afforded a speedy means of transit for the

time, much preferable to the slow and perilous traffic overland, where

rivers had to be crossed and other dangers encountered. Before the days of

steamboats and railways the bateaux were towed up the St. Lawrence and

along the shores of Lake Ontario by horses and cattle when bringing

emigrants and merchandise from Montreal and Quebec. It was usual for the

merchants to visit these places in the spring and buy goods and supplies

sufficient to last them till the following year.

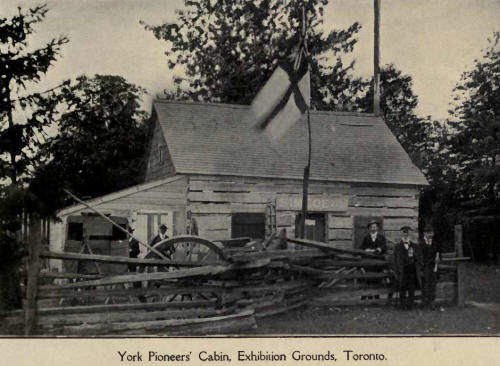

Appearance of the Country.

A solitude of unbroken, silent

woods and bush were the chief features of the new country out of which the

settlers felt that they had to carve homes and build shelters for

themselves and their families, and bravely did they face the stern and

repulsive realities, which meant a lifetime of unwearied toil now before

them. The level stretches were much broken and intersected by rivers,

creeks and lakes, hills and slopes, low swamps and marshes. Much of the

latter features have disappeared and given place to well- tilled fields,

smiling pasture land, fruitful orchards, and comfortable, happy homes,

through the hard toil of the settler. Timber encumbered the ground, the

difficulty of the settler being how to get rid of it. The kinds of timber

varied according to the locality and soil—in the low places being found

the cedar, swamp elm, black ash, willow and tamarack, and in the dry,

elevated localities the birch, beech, maple, oak, pine, spruce, hemlock

walnut, etc.

A considerable portion of the

country along the Niagara, and between Lakes Erie and Ontario is low and

level. When first settled it consisted largely of marsh land, in fact,

some of it remained in that condition until recent years, when large

draining works were put through by the Government for utilizing tracts

which formerly were of no value except for growing huckleberries, people

coming for miles around to get their yearly supply on the marshes. These

low places were also at that time great breeding-places for rattlesnakes.

To avoid the swampy land as much as possible, the early settlers selected

land bordering on the lakes, rivers and creeks, where it could be

conveniently drained. The creeks being fed by the swamps and marshes were

much larger than they are to-day—the clearing up of the country having

caused many of them to become dry.

Much of the land lying -farther

back in the country, on account of its swampy condition and liability to

frost, remained unsettled for many years. Since it has been settled and

drained it has turned out to be the best of soil for farming purposes. The

condition described above applied to many other sections of Canada as

well, for even in the oldest-settled parts, fifty years ago, there was a

great deal of uncleared land, the earliest settlers even then having

considerable bush at the back of their farms. The low price of farm

produce in the early days did not encourage the farmer to hurry up the

clearing of his land, so that he could raise grain and fatten cattle for

the foreign market as he does now so profitably.

The Indians.

The Indians never gave much

trouble to the early settlers of Canada, for the British Government always

treated them fairly. Being of a nomadic nature it was customary for them

to wander around the country and barter with the people, exchanging their

baskets, beadwork, etc., for provisions and clothing. Here and there

through the woods would frequently be found a bark wigwam and the marks of

an Indian camp. The early settlers would often allow them to come into

their houses and stay all night, lying on the floor before the fire

wrapped up in their blankets. If they were hungry they would be made

welcome and have food, etc., given them. It was quite a novel sight to

watch them seated around a big dish of porridge or soup, all eating out of

the same dish.

The Indians, as has just been

said, were well treated by the early settlers, and it is characteristic of

the Indian that he will remain a true friend to those who deal honestly

and fairly by him. It was quite common for an Indian chief to bestow a

belt of wampum upon a white man for favors received. This belt, if hung in

an exposed place, served as a protection to the settler's house; for if

any members of that tribe happened to be on a marauding excursion they

would do no harm to the house in which the belt of wampum was hung as a

token of peace and friendship. In the early days the Indian always carried

his blanket with him wrapped around his body. In travelling they walked

one after the other in Indian file. Sometimes as many as forty or fifty of

them would be seen in a line. They paddled over the lakes and rivers in

canoes made of birch bark. Their customs, habits, mode of living,

dwellings, etc., varied according to the tribe and the locality in which

they located. Basket-making and bead-work were their chief industries. As

a rule most of this work was done by the squaws, the men only exerting

themselves when fishing and hunting. Seated on the ground before the

camp-fire, with their legs crossed one over the other and a bundle of

green splints beside them, the Indians could be seen making baskets. They

would take the splints one by one from the bundle and weave them into a

mat to form the bottom of the basket, sufficient length of the splint

being left to bend sharply at the edge and turn up to help form the sides

and ends; between these were woven more splints until the framework was

finished in the shape desired. A heavy splint or gunwale was put on the

inside at the top to form the rim of the basket. Around this the ends of

the upright splints were wrapped. A heavy splint was placed on the outside

of the rim, and lashed with a lighter splint to keep it in place. Some of

the splints before being used were soaked in a solution of Indian berries,

the solution staining them blue or red, the two principal colors used,

according to the strength obtained by boiling. Sumach bobs or blossoms

were sometimes added to the solution to obtain a drab color. The wood out

of which the splints were made was rim ash (second growth ash) usually

five or six inches in diameter, cut into lengths about six feet long,

first soaked in water (thrown into a creek or brook), after which it was

taken out and pounded or hammered with a big wooden maul until the fibre

of the wood became loose, when it was easily peeled off and cut into

strips of various widths.

The Indians were expert at making

moccasins out of) deerskin. The skin, after being cut the size required,

was sewed with strings or thongs made of finer leather, and ornamented

with colored porcupine quills, and sometimes with beads. Their beads and

colored cloths, of which they made their fancy work, were obtained from

the Indian traders. Their work of this kind was varied, and ofttimes

displayed taste and skill. There had been a Government depot at Niagara

for years for distributing supplies among the Indians. here they brought

their furs and exchanged them for merchandise.

Previous to the advent of the settler many of the

Indians had fields of corn. They ground the grain in rude stone bowls into

a coarse meal, which they made into cakes and baked in the hot ashes. They

also raised beans and pumpkins, but they lived chiefly by the spoils of

fishing and hunting.

In certain Indian resorts are found pieces of

pottery, which, though rude in design, show that they knew something of

the art of making vessels out of clay. They were expert in the use of the

arrow, the heads of which were tipped with pieces of flint carved out of

stone.

The Indian language is very expressive, one word

conveying a great deal of meaning. Their grunt of approval is "Nee." They

applaud their speakers by exclaiming, "Ho! ho!

Ho! ho!"The primitive red men tattooed their bodies and faces, and when on

the war path smeared themselves with different colored pigments. Their

hair they tied in a knot on the top of their heads; into this bunch of

hair was stuck feathers, which gave them a wild and fierce look. The noble

red man, as we see him to-day, is certainly a different individual to what

his ancestors were a century or two ago, and it can scarcely be claimed

that he has been improved by the white man's civilization.

The Wild Animals.

In some localities wild animals were quite numerous

in the early days of settlement. As the country became more thickly

settled, however, they gradually disappeared. r were frequently seen

stalking through the woods, and every now and then a bear

might be seen crossing the path of the settler. The grandmother of the

writer used to say that frequently at night they could hear the wolves

gnawing and crunching the bones that had been thrown outside. A friend

related to the writer that sixty years ago, when his father-in-law and

mother-in-law with their baby child were driving through the woods, not

far from Toronto, on a visit to a friend, they were surrounded by wolves.)

They were obliged to drive furiously to get away from the pack, throwing

out the buffalo robes and blankets for the wolves to tear up, and so delay

their oncoming. They were followed right up to the door of their friend's

house by the animals.

The sheep had to be gathered into folds at night to

keep them from the wolves, and occasionally bruin would get into the pig

pen and carry off one of the pigs. It is told that sometimes the early

settlers carried torches through the woods at night to frighten the wild

animals away.

In order to help rid the country of these pests the

government granted a bounty, i.e., so much per head for the scalps of all

wolves that had been killed. Their pelts could often be seen nailed up,

flesh side out, to the sides of the old log houses, or salted, stretched

on boards, and hung up to be dried and cured by the sun.

Besides the wild animals above mentioned there were

many others. The wild cat, which made its home in the dark woods and

swamps, was the dread of the settler. Porcupines were quite common, and

occasionally the house-dog would come home after an encounter with one of

these animals with his mouth full of quills, which it required pincers to

draw out. The squirrels, red, gray and black, were to be found in

abundance. Snakes in some places were very

unpleasantly plentiful, among them being the rattler, which still makes

its home in the crevices of the rocks lining the Niagara gorge. Snapping

turtles were numerous in certain localities. Foxes were also quite common,

their bark being heard nightly in the clearings. The racoons infested the

swamps and in the fall of the year made annoying raids on the corn fields.

The skunk and weasel depopulated the chicken roosts. Rabbits and hares

were very plentiful and helped out many an enjoy-. able meal. The otter

and beaver were also to be found in many of their favorite haunts along

the small creeks; even now are sometimes found small cleared spots,

called beaver meadows, where these animals formerly cut down the trees and

built a dam.

The whole country, it may be said,

was at that period a hunter's paradise. The settler did not have to go far

to bag game for the dinner table. He could drop his axe, stroll off into

the woods with his gun over his shoulder, and soon return with a supply of

fresh meat for dinner. Birds of all kinds were very numerous; the eagle

could often be seen flying over the tops of the highest trees; the caw,

caw, caw of the crow was always a familiar sound. The turkeys, ducks,

partridges and pheasants were also very plentiful in places.

It is said that deer were so

numerous that they could sometimes be seen pasturing with the cattle, and

had been known to come home with them at night.

The settlers were frequently

obliged to make fires at night near the house to scare the wolves away, so

badly did their nightly howling frighten the women and children of the

family. A snow-storm could invariably be foretold by the howling of the

wolves, which at such times became louder, and more prolonged.

|