|

IF the reader be a weaver, he will forgive the

attempt to make so technical a subject intelligible, and if not a weaver, he

will at least be enabled to form some idea of the skill and patience

exhibited by the harness weavers. To the ordinary reader it may be necessary

to explain that the weaving of a piece of cloth with a continuous pattern,

however elaborate, which goes on repeating itself, is a comparatively simple

matter. Any irregularity of thickness in the weaving, while it will be a

defect, will not entirely destroy the symmetry of the pattern. But it is

quite otherwise with a shawl, which has a beginning and an end. The weaver

commences to weave a border across the bottom, which in some measure repeats

itself along the sides, and blends into a border across the opposite end. To

produce the design correctly, a fixed number of weft threads must be woven

across, between the beginning and the end; not one more, and not one less.

It is manifest that if the weaver beats up his welt threads too closely at

the beginning, he will have the total number in before he arrives at the end

of the shawl, and where, as is often the case, the warp is dyed or stained

in portions to correspond with the design, the latter part of the pattern

will be wholly destroyed. In a power-loom the exact number of weft threads

in a given

space can be regulated with absolute accuracy, but the

hand-loom weaver had to trust to the delicacy of his touch, and therein lay

much of the skill of the harness weaver.

The

yarn required for these Harness Shawls had to be specially prepared. The

finest class of it went under the name of Cashmere. To give the strength

necessary for warp, it consisted of a thread of fine silk round which was

spun a coating of the finest Cashmere wool. This class of yarn was most

successfully made in the neighbourhood of Amiens, in France, and is still

manufactured there for the French market. For the less expensive qualities a

silk or cotton warp was used. The weft was either a carded woollen yarn or a

Botany worsted. These classes of yarn were spun principally in Yorkshire.

There being no railways in those days, some of the spinners in the Bradford

district were accustomed to ride down to Paisley, a journey of several days,

with their yarn samples in their saddle-bags. The goods were sent round by

the steamer from Liverpool to the Clyde.

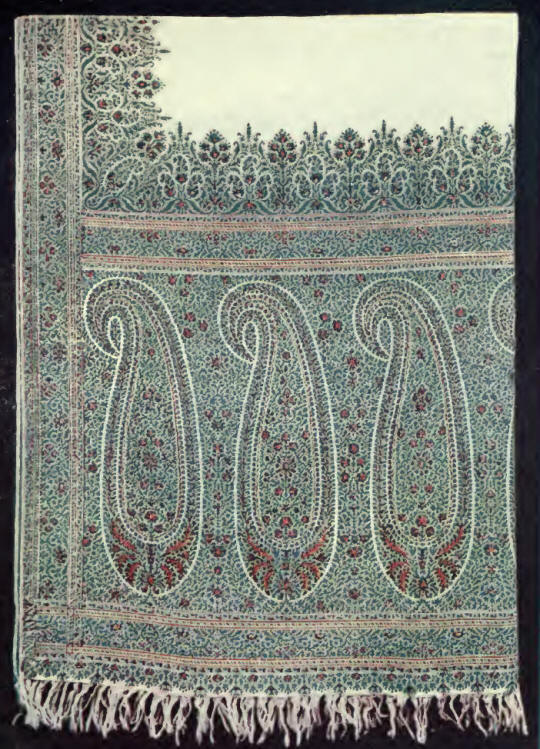

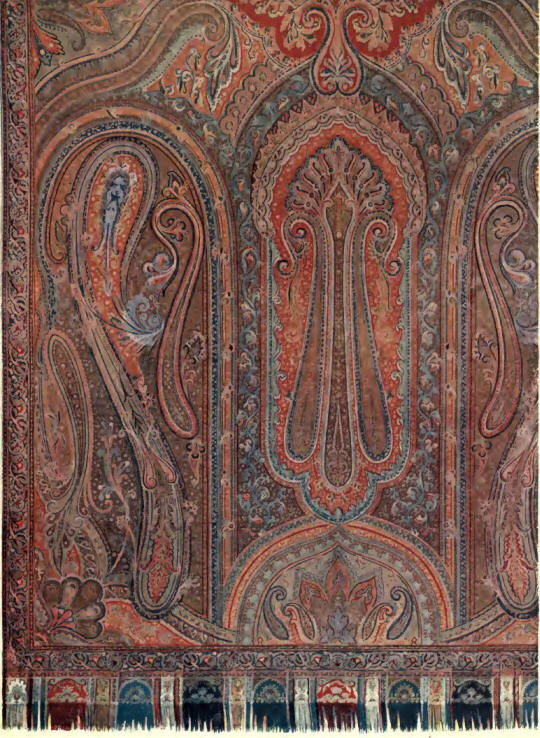

The

dyeing of the warps was one of the first anxieties of the manufacturers, and

required great skill and care. This arose from the custom, as in the Eastern

originals, of having at each end of the shawl a parti-coloured finish,

showing bands of four or five different colours, which became the

ground-work of the terminal borders and formed the warp fringe. This will be

seen in several of the Plates. Between these parti-coloured ends the centre

would be dyed red, if for a red-centered shawl, or black, if this was to be

the colour of the centre. In some cases the warp for the side borders might

be dyed a special colour. It is obvious that this further necessitated much

care in the warping of the web, each length and space requiring exact

measurement and marking. The dyer screwed down the slides of a frame at

these marks, leaving exposed the particular piece that was to be dyed, which

was then dipped in the dye vat. This might occur many times throughout the

length of the shawl. The art of Dyeing thus came to great perfection in

Paisley. While on this subject, it is also worthy to note that, some years

ago, the dyeing of piece goods made of wool or worsted was confined to

Yorkshire. Paisley has since taken a high place in this important industry,

and for this the town is largely indebted to the enterprise of Messrs.

William Fulton & Sons, of Glenfield. Many of the leading dyers in Scotland

and England received their early training in Paisley.

Having now the warp ready, the next thing was to set up

the loom. This was a work of much labour, requiring care and skill in every

detail. Two or three weeks were often required to equip a loom for an

expensive plaid. The weaver bore the cost of this, but a fine spirit of

comradeship prevailed, and willing help at the tyeing of the harness was

freely given by the shop-mates, who in turn received like help when their

time of need came. The boys employed in the weaving-shops also assisted, and

were rewarded by a feast of bread and cheese, which in those days was a

great treat to them, while to their seniors was added the inevitable dram.

On the manufacturer's part the first important point was, of course, the

selection of the design. This was always shown in a miniature form—the

sketch being often a work of art, fit to be framed for wall decoration (see

Plate 11). The next step was to transfer this sketch to design or point

paper, which, when completed, might in some cases cover the floor space of a

good-sized room. This designing required minute care. Each small square must

bear its own colour; no blurring was allowable (see Plate 12).

This design or point paper was first made in Paisley by

Mr. Andrew Blaikie, Engraver, and was printed directly from the copper or

steel plates engraved by himself, some of which are still in use by his

successors, Messrs. Robert Hay & Son.

The

squares represented the point at which a weft thread crossed a warp thread,

so that every weft shot that was to complete the shawl could be counted, and

there would be sometimes as many as 150,000 weft threads crossing the loom

in one harness plaid.

If Paisley Shawls were

now manufactured, the next step would be the card cutting of the design. But

in those early days the Jacquard, although long before invented, was not in

use by the Paisley weavers, and instead of the card cutter, the work of the

flower lasher came into play, which we may now attempt to describe.

The composition of the design was usually limited to

six, seven, or eight colours, and the ground colour upon which these

figuring colours were introduced. The first point was to determine the

sequence in which these colours would run, say: 1, claret; 2, green; 3,

yellow; 4, blue; and so on.

The flower lasher

had before him a frame not unlike that of a card cutter, but in addition, an

upright web of strong linen thread called a "simple." This is illustrated in

Plate 12. The simple was fixed tight before the lasher, each thread standing

before each upright square of the design. A straight-edge placed across the

design revealed only one minute horizontal line of colour. The lasher had at

his left hand a bobbin of strong cotton thread, and running his eye from

left to right, if claret covers two squares, he interlaces the cotton thread

behind the corresponding threads of the simple, and so on across the face of

the design. This is now knotted up and called a "lash." The next colour,

green, is treated in like manner, and so on, till all the colours are gone

over, and when completed they form a "bridle." Each lash represented one

colour, and each bridle the whole of the colours in one line of weft. The

twines of the simple were attached overhead to the tail cords, which were

passed over pulleys and connected with the harness twines. At the. lower end

of each of these harness twines was a metal eye, called a "mail," through

which the warp thread passed, with a weight below in the form of a thin

piece of lead, to bring it down and keep it straight. See Plate 13.

It was the manipulation of these lashes on the simple

that formed the work of the draw-boy. Drawing out each lash in succession,

the boy grasped the threads of the simple, thus separating them from the

others, and pulled them down, so raising the requisite warp threads to form

the shed through which the shuttle passed.

|