Larger than Life

A five star hotel is both a fantasy and a

factory. The fantasy is the world the guests enter when they step over the front door. In

such a world champagne flows and the patisserie chef can spin spring flowers out of sugar:

beds are turned down and lamps lit at bedtime, clean towels appear before each bath, the

water is always hot, lifts always work and a boiled egg for breakfast is as perfectly

cooked as last night's poached salmon.

"People like to be made to feel at

home", says Jack Maguire who spent 40 years in what he describes as a kind of

vocation. "They want to be cosseted. They want privacy and they want respect".

What people like, head banqueting waiter Renato del Vecchio learned, is to be greeted by

someone who knows what they like and exactly how they like it to be done. But whether the

rich and famous want to feel at home or homelier bodies want to feel rich and famous - the

illusion has to work.

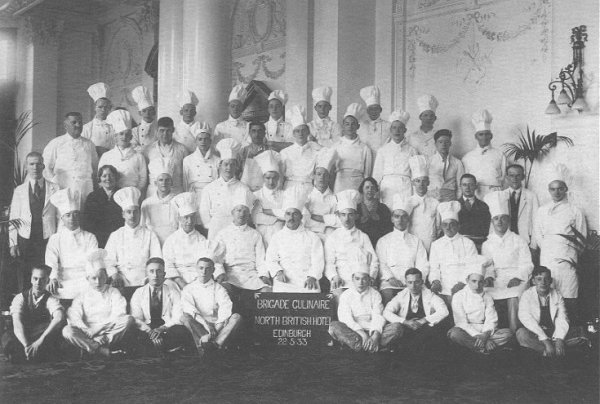

Brigade de cuisine: members of an underworld where everyone

speaks French

The factory is the extraordinary industry which

creates this wonderful world of make-belief from an odd combination of advanced

technology, thorough training, and sheer hard work. Breakfast is served for 300 or more

because the breakfast chef started work at 3.30am. Should every guest in the hotel decide

to have a bath at the same time water will flow from the hot tap thanks to the chief

engineer, his maintenance team and a boiler room which would not have looked out of place

in the Queen Mary. Out of sight the waste from guests' plates is compressed by machine and

consigned to the deep blue sea. And if the rugby team stays up all night the general

manager is thankful that his chief engineer decided to switch over to energy saving lamps.

A hotel is larger than life which means it has

all the problem of home many times over. "Imagine a normal house", says chief

engineer Ian Banyard, "then multiply it by 200 and you get some idea of what it takes

to run this place". The North British was essentially a self-contained village which

until the early 1980s still employed not only a baker, an electrician, a carpenter and a

plumber but also a French polisher, an upholsterer and a slater. Ian Banyard reduced the

hotel's bill for light bulbs form £7,000 to £5,000 a year by the simple means of buying

better quality bulbs, transferring to energy saving lamps and persuading staff to switch

off lights when rooms were not in use. He saved £800 a year alone in the huge Sir Walter

Scott banqueting room where fifteen chandeliers burned fifteen 60 watt light bulbs each

from 6am until after midnight as breakfast turned into a ceaseless round of catering until

the last dinner plate and wine glass gave way to next day's breakfast cups again.

Ian Banyard arrived at the North British in 1983

when the hotel was being wound down for closure and refurbishment. Business continued for

five more years with the help of cosmetic redecoration - "a little lipstick here, a

little rouge there" as Banyard puts it. But the grand old lady had grown decidedly

shabby and beyond the banquets and dinner-dances the veneer of glamour had worn very thin.

"The wiring was frayed, the pipe-work was rotten, I was scared to take off the

lagging in case the pipes fell to bits".

The boilers which had once pumped steam into the

sleeping cars waiting at Platform 19 in the station down below the fourth basement,

struggled to meet the demands of bathing guests. Old, outdates and installed in a way

which defied access for maintenance, some of the water tanks contained a thick layer of

silt which caused a rich, "peaty" flow from the taps when too many baths were

run at the same time.

Next

Page Next

Page

|