|

Yosemite is so wonderful that

we are apt to regard it as an exceptional creation, the only valley of its

kind in the world; but Nature is not so poor as to have only one of

anything. Several other yosemites have been discovered in the Sierra that

occupy the same relative positions on the range and were formed by the same

forces in the same kind of granite. One of these, the Hetch Hetchy Valley,

is in the Yosemite National Park, about twenty miles from Yosemite, and is

easily accessible to all sorts of travelers by a road and trail that leaves

the Big Oak Flat road at Bronson Meadows a few miles below Crane Flat, and

to mountaineers byway of Yosemite Creek basin and the head of the middle

fork of the Tuolumne.

It is said to have been

discovered by Joseph Screech, a hunter, in 1850, a year before the discovery

of the great Yosemite. After my first visit to it in the autumn of 1871, I

have always called it the "Tuolumne Yosemite," for it is a wonderfully exact

counterpart of the Merced Yosemite, not only in its sublime rocks and

waterfalls but in the gardens, groves and meadows of its flowery park-like

floor. The floor of Yosemite is about four thousand feet above the sea; the

Hetch Hetchy floor about thirty-seven hundred feet. And as the Merced River

flows through Yosemite, so does the Tuolumne through Hetch Hetchy. The walls

of both are of gray granite, rise abruptly from the floor, are sculptured in

the same style and in both every rock is a glacier monument.

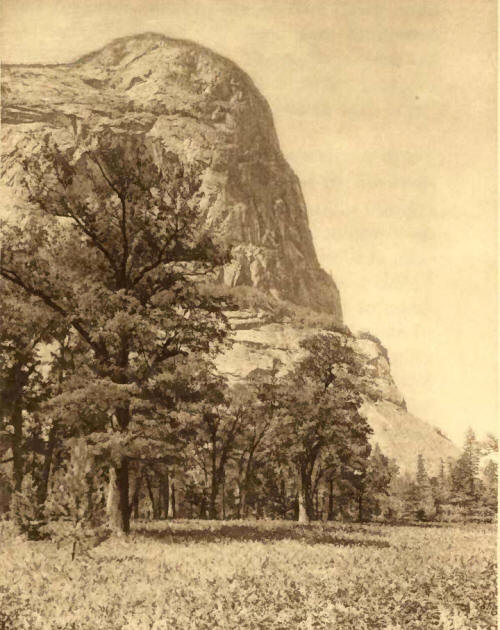

Standing boldly out from the

south wall is a strikingly picturesque rock called by the Indians, Kolana,

the outermost of a group twenty- three hundred feet high, corresponding with

the Cathedral Rocks of Yosemite both in relative position and form. On the

opposite side of the Valley, facing Kolana, there is a counterpart of El

Capitan that rises sheer and plain to a height of eighteen hundred feet, and

over its massive brow flows a stream which makes the most graceful fall I

have ever seen. From the edge of the cliff to the top of an earthquake talus

it is perfectly free in the air for a thousand feet before it is broken into

cascades among, talus boulders. It is in all its glory in June,, when the

snow is melting fast, but fades and'. vanishes toward the end of summer. The

only fall I know with which it may fairly be compared is the Yosemite Bridal

Veil; but it excels even that favorite fall both in height and airyfairy

beauty and behavior. Lowlanders are apt to suppose that mountain streams in

their wild career over cliffs lose control of themselves and tumble in a

noisy chaos of mist and spray. On the contrary, on no part of their travels

are they more harmonious and self-controlled. Imagine yourself in Hetch

Hetchy on a sunny day in June, standing waist-deep in grass and flowers (as

I have often stood), while the great pines sway dreamily with scarcely

perceptible motion. Looking northward across the Valley you see a plain,

gray granite cliff rising abruptly out of the gardens and groves to a height

of eighteen hundred feet, and in front of it Tueeu1a1asilvery scarf burning

with irised sun-fire. In the first white outburst at the head there is

abundance of visible energy, but it is speedily hushed and concealed in

divine repose, and its tranquil progress to the base of the cliff is like

that of a 'downy feather in a still room. Now observe the fineness and

marvelous distinctness of the various sun-illumined fabrics into which the

water is woven; they sift and float from form to form down the face of that

grand gray rock in so leisurely and unconfused a manner that you can examine

their texture, and patterns and tones of color as you would a piece of

embroidery held in the hand. Toward the top of the fall you see groups of

booming, comet-like masses, their solid, white heads separate, their tails

like combed silk interlacing among delicate gray and purple shadows, ever

forming and dissolving, worn out by friction in their rush through the air.

Most of these vanish a few hundred feet below the summit, changing to varied

forms of cloud-like drapery. Near the bottom the width of the fall has

increased from about twenty-five feet to a hundred feet. Here it is composed

of yet finer tissues, and is still without a trace of disorder - air, water

and sunlight woven into stuff that spirits might wear.

So fine a fall might well

seem sufficient to glorify any valley; but here, as in Yosemite, Nature

seems in nowise moderate, for a short distance to the eastward of Tueeulala

booms and thunders the great Hetch Hetchy Fall, Wapama, so near that you

have both of them in full view from the same standpoint. It is the

counterpart of the Yosemite Fall, but has a much greater volume of water, is

about seventeen hundred feet in height, and appears to be nearly vertical,

though considerably inclined, and is dashed into huge outbounding bosses of

foam on projecting shelves and knobs. No two falls could be more unlike -

Tueeulala out in the open sunshine descending like thistledown; Wapama in a

jagged, shadowy gorge roaring and thundering, pounding its way like an

earthquake avalanche.

Besides this glorious pair

there is a broad, massive fall on the main river a short distance above the

head of the Valley. Its position is something like that of the Vernal in

Yosemite, and its roar as it plunges into a surging trout- pool may be heard

a long way, though it is only about twenty feet high. On Rancheria Creek, a

large stream, corresponding in position with the Yosemite Tenaya Creek,

there is a chain of cascades joined here and there with swift flashing

plumes like the one between the Vernal and Nevada Falls, making magnificent

shows as they go their glacier-sculptured way, sliding, leaping, hurrahing,

covered with crisp clashing spray made glorious with sifting sunshine. And

besides all these a few small streams come over the walls at wide intervals,

leaping from ledge to ledge with bird-like song and watering many a hidden

cliff-garden and fernery, but they are too unshowy to be noticed in so grand

a place.

The correspondence between

the Retch Hetchy walls in their trends, sculpture, physical structure, and

general arrangement of the main rock-masses and those of the Yosemite Valley

has excited the wondering admiration of every observer. We have seen that El

Capitan and Cathedral rocks occupy the same relative positions in both

valleys; so also do their Yosemite points and North Domes. Again, that part

of the Yosemite north wall immediately to the east of the Yosemite Fall has

two horizontal benches, about five hundred and fifteen hundred feet above

the floor, timbered with golden-cup oak. Two benches similarly situated and

timbered occur on the same relative portion of the Hetch Hetchy north wall,

to the east of Wapama Fall, and on no other. The Yosemite is bounded at the

head by the great Half Dome. Hetch Hetchy is bounded in the same way, though

its head rock is incomparably less wonderful and sublime in form.

The floor of the Valley is

about three and a half miles long, and from a fourth to half a mile wide.

The lower portion is mostly a level meadow about a mile long, with the trees

restricted to the sides and the river-banks, and partially separated from

the main, upper, forested portion by a low bar of glacier-polished granite

across which the river breaks in rapids.

The principal trees are the

yellow and sugar pines, digger pine, incense cedar, Douglas spruce, silver

fir, the California and golden-cup oaks, balsam cottonwood, Nuttall's

flowering dogwood, alder, maple, laurel, tumion, etc. The most abundant and

influential are the great yellow or silver pines like those of Yosemite, the

tallest over two hundred feet in height, and the oaks assembled in

magnificent groves with massive rugged trunks four to six feet in diameter,

and broad, shady, wide-spreading heads. The shrubs forming conspicuous

flowery clumps and tangles are manzanita, azalea, spiraa, brier-rose,

several species of ceanothus, calycanthus, philadeiphus, wild cherry, etc.;

with abundance of showy and fragrant herbaceous plants growing about them or

out in the open in beds by themselves - lilies, Mariposa tulips, brodiaas,

orchids, iris, spraguea, draperia, collomia, collinsia, castilleja,

nemophila, larkspur, columbine, goldenrods, sunflowers, mints of many

species, honeysuckle, etc. Many fine ferns dwell here also, especially the

beautiful and interesting rock-ferns - pe1la, and cheilanthes of several

species - fringing and rosetting dry rock-piles and ledges; woodwardia and

asplenium on damp spots with fronds six or seven feet high; the delicate

maidenhair in mossy nooks by the falls, and the sturdy, broad-shouldered

pteris covering nearly all the dry ground beneath the oaks and pines.

It appears, therefore, that

Hetch Hetchy Valley, far from being a plain, common, rockbound meadow, as

many who have not seen it seem to suppose, is a grand landscape garden, one

of Nature's rarest and most precious mountain temples. As in Yosemite, the

sublime rocks of its walls seem to glow with life, whether leaning back in

repose or standing erect in thoughtful attitudes, giving welcome to storms

and calms alike, their brows in the sky, their feet set in the groves and

gay flowery meadows, while birds, bees, and butterflies help the river and

waterfalls to stir all the air into music - things frail and fleeting and

types of permanence meeting here and blending, just as they do in Yosemite,

to draw her lovers into close and confiding communion with her.

Sad to say, this most

precious and sublime feature of the Yosemite National Park, one of the

greatest of all our natural resources for the uplifting joy and peace and

health of the people, is in danger of being dammed and made into a reservoir

to help supply San Francisco with water and light, thus flooding it from

wall to wall and burying its gardens and groves one or two hundred feet

deep. This grossly destructive commercial scheme has long been planned and

urged (though water as pure and abundant can be got from sources outside of

the people's park, in a dozen different places), because of the comparative

cheapness of the dam and of the territory which it is sought to divert from

the great uses to which it was dedicated in the Act of 1890 establishing the

Yosemite National Park.

The making of gardens and

parks goes on with civilization all over the world, and they increase both

in size and number as their value is recognized. Everybody needs beauty as

well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and

cheer and give strength to body and soul alike. This natural beauty- hunger

is made manifest in the little windowsill gardens of the poor, though

perhaps only a geranium slip in a broken cup, as well as in the carefully

tended rose and lily gardens of the rich, the thousands of spacious city

parks and botanical gardens, and in our magnificent national parks - the

Yellowstone, Yosemite, Sequoia, etc. - Nature's sublime wonderlands, the

admiration and joy of the world. Nevertheless, like anything else worth

while, from the very beginning, however well guarded, they have always been

subject to attack by despoiling gain-seekers and mischief-makers of every

degree from Satan to Senators, eagerly trying to make everything immediately

and selfishly commercial, with schemes disguised in smug- smiling

philanthropy, industriously, shampiously crying, "Conservation,

conservation, panutilization," that man and beast may be fed and the dear

Nation made great. Thus long ago a few enterprising merchants utilized the

Jerusalem temple as a place of business instead of a place of prayer,

changing money, buying and selling cattle and sheep and doves; and earlier

still, the first forest reservation, including only one tree, was likewise

despoiled. Ever since the establishment of the Yosemite National Park,

strife has been going on around its borders and I suppose this will go on as

part of the universal battle between right and wrong, however much its

boundaries may be shorn, or its wild beauty destroyed.

The first application to the

Government by the San Francisco Supervisors for the commercial use of Lake

Eleanor and the Hetch Hetchy Valley was made in 1903, and on December 22 of

that year it was denied by the Secretary of the Interior, Mr. Hitchcock, who

truthfully said: -

Presumably the Yosemite

National Park was created such by law because of the natural objects of

varying degrees of scenic importance located within its boundaries,

inclusive alike of its beautiful small lakes, like Eleanor, and its majestic

wonders, like Hetch Hetchy and Yosemite Valley. It is the aggregation of

such natural scenic features that makes the Yosemite Park a wonderland which

the Congress of the United States sought by law to reserve for all coming

time as nearly as practicable in the condition fashioned by the hand of the

Creator - a worthy object of national pride and a source of healthful

pleasure and rest for the thousands of people who may annually sojourn there

during the heated months.

The most delightful and

wonderful campgrounds in the Park are its three great valleys - Yosemite,

Hetch Hetchy, and Upper Tuolumne; and they are also the most important

places with reference to their positions relative to the other great

features - the Merced and Tuolumne Canons, and the High Sierra peaks and

glaciers, etc., at the head of the rivers. The main part of the Tuolumne

Valley is a spacious flowery lawn four or five miles long, surrounded by

magnificent snowy mountains, slightly separated from other beautiful

meadows, which together make a series about twelve miles in length, the

highest reaching to the feet of Mount Dana, Mount Gibbs, Mount Lyell and

Mount McClure. It is about eighty-five hundred feet above the sea, and forms

the grand central High Sierra camp-ground from which excursions are made to

the noble mountains, domes, glaciers, etc.; across the range to the Mono

Lake and volcanoes and down the Tuolumne Caņon to Hetch Hetchy. Should Hetch

Hetchy be submerged for a reservoir, as proposed, not only would it be

utterly destroyed, but the sublime caņon way to the heart of the High Sierra

would be hopelessly blocked and the great camping ground, as the watershed

of a city drinking system, virtually would be closed to the public. So far

as I have learned, few of all the thousands who have seen the park and seek

rest and peace in it are in favor of this outrageous scheme.

One of my later visits to the

Valley was made in the autumn of 1907 with the late William Keith, the

artist. The leaf-colors were then ripe, and the great godlike rocks in

repose seemed to glow with life. The artist, under their spell, wandered day

after day along the river and through the groves and gardens, studying the

wonderful scenery; and, after making about forty sketches, declared with

enthusiasm that although its walls were less sublime in height, in

picturesque beauty and charm Hetch Hetchy surpassed even Yosemite.

That any one would try to

destroy such a place seems incredible; but sad experience shows that there

are people good enough and bad enough for anything. The proponents of the

dam scheme bring forward a lot of bad arguments to prove that the only

righteous thing to do with the people's parks is to destroy them bit by bit

as they are able. Their arguments are curiously like those of the devil,

devised for the destruction of the first garden - so much of the very best

Eden fruit going to waste; so much of the best Tuolumne water and Tuolumne

scenery going to waste. Few of their statements are even partly true, and

all are misleading.

Thus, Hetch Hetchy, they say,

is a "low- lying meadow." On the contrary, it is a high- lying natural

landscape garden, as the photographic illustrations show.

"It is a common minor

feature, like thousands of others." On the contrary it is a very uncommon

feature; after Yosemite, the rarest and in many ways the most important in

the National Park.

"Damming and submerging it

one hundred and seventy-five feet deep would enhance its beauty by forming a

crystal-clear lake." Landscape gardens, places of recreation and worship,

are never made beautiful by destroying and burying them. The beautiful sham

lake, forsooth, would be only an eyesore, a dismal blot on the landscape,

like many others to be seen in the Sierra. For, instead of keeping it at the

same level all the year, allowing Nature centuries of time to make new

shores, it would, of course, be full only a month or two in the spring, when

the snow is melting fast; then it would be gradually drained, exposing the

slimy sides of the basin and shallower parts of the bottom, with the

gathered drift and waste, death and decay of the upper basins, caught here

instead of being swept on to decent natural burial along the banks of the

river or in the sea. Thus the Hetch Hetchy dam-lake would be only a rough

imitation of a natural lake for a few of the spring months, an open

sepulcher for the others.

"Hetch Hetchy water is the

purest of all to be found in the Sierra, unpolluted, and forever

unpollutable." On the contrary, excepting that of the Merced below Yosemite,

it is less pure than that of most of the other Sierra streams, because of

the sewerage of campgrounds draining into it, especially of the Big Tuolumne

Meadows camp-ground, occupied by hundreds of tourists and mountaineers, with

their animals, for months every summer, soon to be followed by thousands

from all the world.

These temple destroyers,

devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for

Nature, and, instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the mountains, lift

them to the Almighty Dollar.

Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam

for water- tanks the people's cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple

has ever been consecrated by the heart of man. |