|

By LIONEL W. HINXMAN, H.M. Geological Survey.

THERE is perhaps no more striking group of mountains

in the British Islands than those strange isolated masses of red sandstone

which rise like huge monoliths from the tumbled grey sea of primitive gneiss

along the western seaboard of Sutherland and Ross-shire.

They have been graphically described by Macculloch,

who, writing at a time when the beauties of Highland scenery were yet

undiscovered, characterises them in the following words:—" Round about there

are four mountains, which seem as if they had tumbled from the clouds,

having nothing to do with the country or each other, either in shape,

material, position, or character, and which look very much as if they were

wondering how they got there. Which of them all is the most rocky and

useless, is probably known to the sheep; human organs distinguish little but

stone,—black precipices when the storm and the rain are drifting by, and

when the sun shines, cold, bright summits that seem to rival the snow." Hugh

Miller, who was perhaps the first to perceive the unique character of these

mountains from a scenic point of view, has drawn their picture with a pencil

dipped in glowing colours, and invested them with a singular and poetic

charm; while his description has been equalled, if not surpassed, by Dr A.

Geikie, in his "Scenery of Scotland."

Rising directly from the gneiss plateau, which, though

carved into innumerable glens, hollows, and ridges, yet preserves in its

eminences a tolerably uniform level, these heights possess more of the true

mountain form than most of our Scottish hills, where the eye is gradually

led up from spur to spur to the culminating peak, which often rises little

above the surrounding ridges. Here, however, the whole mass and height of

each mountain is taken in at a glance; while their strange isolation, and

incongruity, both in form and colouring, with their surroundings, give to

these peaks a fascination and impressiveness which we look for in vain

amongst such mountain masses as those of the Cairngorm range.

It is hard to decide to which of the group the

superiority should be given. Quinag, with its mile-long wall of precipice

fronting the western sea, and the magnificent bastions of Sail Garbh; the

twin peaks of Coul Mbr, one keeping guard over the depths of the Corrie Dubh,

the other frowning above those mighty terraces which fall, in steps of a

thousand feet, down to the wild loneliness of Gleann na Laoigh; the towering

cone of Coul Beag; the fantastic pinnacles of Stack Polly; the long serrated

ridge of Ben More Coigach,—have all their particular charm.

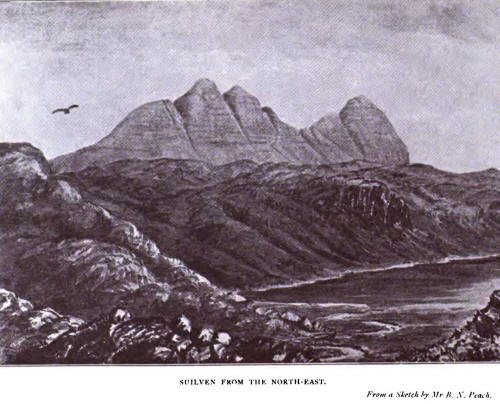

Suilven, however, though yielding in height to most of

his neighbours, yet combines more of the characteristics of a true mountain

than can perhaps be found in any one of them. Few mountains, too, present a

greater diversity of aspect. The long knife-edged crest, deeply cloven in

three by narrow couloirs, that rises above the lonely shores of Loch

Veyattie; the double peak that starts up against the horizon, and arrests

the attention as one approaches Alltnagealgach from the east; or, most

striking of all, the wonderfully symmetrical cone that looks out over Loch

Inver and the sea; in days of storm, when the black peak looms for a moment

through the flying cloud-wrack, and the ragged mist swirls round the crags;

or flaming up in the long afterglow of summer evenings, a pyramid of fire

against the soft pale green of the eastern sky,—from every point of view,

and under every condition, Suilven will always hold his place as unique

amongst the mountains of the west.

Suilven lies in the heart, and is indeed the

sanctuary, of the deer forest of Glen Canisp, from which, at the time of our

ascent, both tourists and geologists were rigorously excluded, for the then

lessee was of the opinion that the latter at least were "of no use but to

frighten the deer and upset the Bible."

From the position and comparative inaccessibility of

the mountain the ascent is not often made, and during the two previous

summers, spent in surveying the surrounding country, I had cast many longing

looks towards the formidable eastern peak, said to be very difficult to any

one but an expert climber. It was not, however, till our third summer in

these regions that we began to realise that our campaign in Assynt was

drawing to a close, while Suilven still remained unconquered.

We were then staying at the farmhouse of Achumore,

which lies about two miles west of Inchnadamph, delightfully situated among

the green flower-covered knolls and hollows of the limestone plateau that

slopes up in alternate grassy lawn and miniature escarpment from the

northern shore of Loch Assynt to the grey stony flanks of Glasven and Ben

Uidhe. Past the farmhouse flows a burn of the purest water, which has its

source in two powerful springs at the foot of Glasven, and is, even at its

birth, a stream of considerable volume. These springs, supplied from the

subterranean chambers of the limestone, seem almost unaffected by ordinary

rain or drought; and the burn flows, in a perennially clear and full stream,

through the grassy meadows of Achumore, gay in summer with purple orchis and

yellow globe-flower, and, dashing over each successive escarpment in a

series of miniature waterfalls, mingles with the waters of Loch Assynt in

Ardvreck Bay, beneath the shadow of the old castle.

It was from these pleasant quarters that I, with my

friends H- and C--, started, on a lovely morning in early June, for the long

contemplated climb over the ridge of Suilven. We had determined to drive as

far as Loch Awe, which lies about six miles eastwards of Inchnadamph, on the

road to Lairg, and is the nearest point on any accessible road to the

eastern end of the mountain.

Ardvreck Castle, the ruined house of Calda, and the

comfortable hostelry of Inchnadamph—well known to every angler who has

visited that paradise of the trout- fisher, Western Sutherland—were soon

passed; and as we bowled along the smooth road beneath the grey cliffs of

Stronchrubie, where the goats were picking their way along invisible ledges,

the crisp morning air, filled with the music of bird voices,—the cheery crow

of the grouse cock, the wild cry of the peregrine wheeling about the crags

overhead, the whistle of curlew and greenshank along the river

flats—produced in one that indescribable feeling of enthusiasm with which

one starts for a mountain expedition in the Highlands. An hour's drive

brought us to the shores of Loch Awe, where the trout were rising merrily

along the edge of the reed-beds, dimpling the glassy surface, in which each

little wooded islet lay reflected as in a mirror.

Here we left our vehicle, and, crossing the Loanan

burn at the point where it issues from the loch, began the ascent of the

long quartzite slope, thickly strewn with boulders and moraine d/bris, which

forms the eastern spur of Canisp. A rough and tedious climb of about two

miles brought us to the crest of this subsidiary ridge, and, calling a halt,

we sat down to enjoy a rest and a pipe before descending into the deep glen

that lay between us and our goal. At our feet the ground fell in an abrupt

escarpment to the plateau from which rises the long, steep, southern face of

Canisp, stretching away on our right; its talus slopes, red with debris

fallen from the porphyry precipices, which girdle it with successive lines

of battlemented crag that are relieved here and there by greener spots where

the alternating slopes of more yielding sandstone are covered by a scanty

herbage.

Away on our left, beyond the long trench-like loch—

Loch Fada—which fills the narrow glen beneath, we could catch the glitter of

the sunlight on the bays of Cama Loch and see, rising beyond, the green

knolls and white houses of Elphin; while farther still in the distance

stretched the smooth heather-covered slopes of the Cromalt Hills. Right in

front, on the farther side of the glen, rose the great northern wall of

Suilven; and as we looked at that seamed and rugged precipice, we realised

that a stiff task lay before us. No time was to be lost, however, so

knocking out our pipes, we scrambled down the steep descent to the plateau

below, and keeping for a mile or so along the top of the cliffs that rise

from the northern shore of Loch Fada, finally descended into the gloomy

depths of Glen Dorcha (the glen of darkness), and crossed the stream that

connects Loch Fada with Loch Ganimhich. The south side of the glen is here

very steep, and overgrown with long heather, than which there is nothing

more trying to climb through, one's boots slipping on the stems when

inclined downwards in a peculiarly aggravating manner. However, the top was

reached at last, and a tramp of nearly two miles over well-polished knolls

of grey gneiss, interspersed with peaty flats and small shallow lochans,

brought us to the foot of the eastern peak, where the real work of the day

was to begin.

For the benefit of those who are unacquainted with

Suilven, a brief description of the form of the mountain may here be given.

Rising steeply from a comparatively even base, it

sweeps up rapidly in successive ledge and precipice, presenting an almost

unbroken wall of rock save where the mountain torrents have cut deep gashes

down its sides. In fact, looking at the mountain from a little distance

either on the north or south, it appears as if these formidable-looking

con/airs were the only possible means by which the top could be reached. The

crest of the mountain forms a ridge about a mile and a half in length,

divided by deeply- cut clefts into three peaks of unequal height. These are

known respectively as Meall Bheag (little hill), Meall Mheadhonach (middle

bill), and Caisteal Liath (the grey castle). The latter forms the western

extremity of the ridge, overlooking Loch Inver, and is the highest of the

three, the Ordnance cairn giving the summit as 2399 feet above sea-level.

Meall Mheadhonach is about ioo feet lower, while Meall Bheag barely reaches

2000 feet.

The clefts—to which the striking appearance of the

mountain, when seen in flank, is chiefly due—mark the position of two faults

which cut through the ridge from north to south, letting down the sandstone

strata in each instance to the west, though the forces of denudation have

long since obliterated all difference of level at the summit, which at

the,present time is in each case actually lower on the upthrow, or unmoved

side, of the line of fracture. A probable explanation of this fact may be

found by supposing that a band of harder rock was successively let down a

step, and thus the wasting and wearing down process went on more rapidly in

the softer strata on the upper or eastern side of each line of fault. The

natural drainage of the hill, taking advantage of the course of these

faults, has cut deep gullies filled with loose debris down the talus slopes.

This debris is inclined at so steep an angle, that a touch of the foot is

often sufficient to set the whole mass in motion. Where, however, the lines

of fracture cross the ridge, one side of each cleft forms a more or less

perpendicular wall of rock, the other a steep broken slope; and it is in

crossing these nicks that the only real difficulty of the climb is found.

The mountain is composed throughout of red gritty

sandstone, which generally gives good foothold, and, though apt to crumble

in places, is never slippery. The sandstone lies in almost horizontal beds

of nearly uniform thickness, which can be traced, like lines of masonry,

along the sides of the hill, and are carved along the wind-swept crest into

a thousand forms of bastion, turret, and pinnacle, thus giving that

architectural appearance which is so characteristic of these sandstone

mountains.

The western peak is symmetrically dome-shaped, and

plunges down at its farther extremity in an almost perpendicular precipice

to the talus slope, which sweeps out, in bold parabolic curves, from the

foot of the cliff to the gneiss plateau below.

Meall Bheag, though formidable enough, is less

precipitous on its outer side, and, rising from a considerably higher level

to a considerably lesser attitude, cannot compare in grandeur with the great

mural precipieces of Caisteal Liath.

To reach the top of Meall Bheag was now our aim, and,

after reconnoitring it on all sides, we determined to attack the peak at the

south-east corner, where the first slopes seemed less steep than elsewhere.

A tolerably easy scramble up the grassy incline,

strewn with fallen blocks of sandstone of all sizes, brought us to the foot

of the escarpment, where the real climb might be said to begin. Precipitous

though this part of the hill appears when seen from a distance, it is yet so

broken into ledge and terrace by the unequal weathering of the sandstone

courses, that to a firm foot and steady eye it presents no greater

difficulty than that involved in going up a somewhat steep and irregular

staircase, with steps varying from one to three feet in height.

Occasionally, however, a higher step of six feet or more blocked the way,

and had to be followed along until a break, or a succession of convenient

crevices, was found, by which it could be surmounted. In this way, by a

system of judicious zig-zagging, we soon reached the top, which forms a

nearly fiat plateau, covered with scanty grass and loose sandy debris.

Crossing to the western end, where it overlooks the

cleft between Meall Bheag and Meall Mheadhonach, we became aware that

between us and our next goal there was indeed a great gulf fixed. The cliff

on the east side of this gully is not only vertical, but actually overhangs,

as can be distinctly seen from any point on the south side of the mountain ;

and to get down on to the narrow saddle that bridges the chasm between the

two peaks seemed at first an impossibility.

Of course we could have solved the problem by going

down again to the foot of Meall Bheag, and ascending Meal! Mheadhonach by

means of the dividing cleft. But this was an ignominious way out of the

difficulty not to be entertained for a moment. We had come out to climb

Suilven from end to end, and climb him we would.

So, after craning over the horrid gulf for some little

time, and examining the rocks on all sides, we came to the conclusion that

nothing but a goat could get down there, and that the position must be

turned in flank, or not at all.

Crossing over, then, to the northern side of the peak,

we let ourselves cautiously over the edge of the cliff, gradually worming

our way down from ledge to ledge wherever a good opportunity for-a drop

occurred, but always working westwards towards the cleft, until we found

ourselves almost immediately underneath the overhanging rock from which we

had just before looked down. This was a bit of work requiring great caution

and a steady head, for at nearly every point the cliff fell sheer down to a

depth of several hundred feet, and a slip at any time would have been fatal.

Otherwise the foothold was good, and the ledges always sufficiently broad to

enable one to move along with comparative safety, though here and there we

had to crawl on hands and knees, the shelf above projecting too far to allow

of walking upright. However, all went well, and, one after another, we crept

round the last corner, and established ourselves on the narrow rock of

porphyry which connects the two peaks.

Looking down the tremendous gash, through which the

wind was sweeping with fearful force, we saw the distant landscape set, as

it were, in a narrow frame of perpendicular walls that plunged down on

either side. The entire absence of middle distance, and the immense extent

of atmosphere through which one looked to the country beneath, gave a very

curious and striking character to this mountain picture, enhanced by the

startling contrast between the dark walls of the cleft and the sunny

landscape far below.

In spite, however, of the wonderful view, this was too

draughty a spot in which to linger, and we were soon attacking the farther

side of the chasm.

The first few feet surmounted, leading from the neck

to the slope above, the rest was not difficult, this side of Meall

Mheadhonach sloping at an easy angle compared with the face that we had just

come down. A climb of about 400 feet brought us to the crest of the middle

peak, which forms a narrow ridge, in places less than a yard in width, and

falling abruptly on either hand to the edge of the cliffs that flank each

side of the mountain. So narrow was the path, and so furious the wind that

swept across it, that we found it advisable to descend a little on the

leeward side, and thus escape the fierce gusts that threatened at times to

sweep us off our feet.

At the highest point of the ridge there is a

shepherd's cairn, and round this were scattered many eagles' casts,- oval

concretions of wool, hair, and feathers mixed with fragments of bone, which

the eagle, like ail birds of prey, throws up, after assimilating the more

digestible parts of its food. We also found a few feathers, which we carried

off as trophies, though we were not fortunate enough to see any of the

birds, a pair of whom at that time had their eyrie in a high rock in the

glen below. Golden eagles are still tolerably plentiful in this part of

Sutherland, and being preserved are believed to be increasing in numbers. My

friend P—, who a few days before our expedition had observed the birds leave

the eyrie, has seen as many as four eagles, probably a pair with their

young, hunting together in Glen Canisp; and I have watched them sailing in

lazy circles for hours together round the topmost point of Quinag.

The sea eagle is now much more rare, but a pair used

to build regularly on the cliffs near Cape Wrath, and another near the

Whitten Head.

At the western end of the ridge we came to another

rather nasty bit,—a drop over several feet of perpendicular rock on to the

slope that leads down to the Bealach Mor, as the col between Meall

Mheadhonach and Caisteal Liath is called. This however, I believe, might

have been avoided by going a little farther down the ridge on the south

side, and working round the corner as we had previously done on Meall Bheag.

The rest of the descent to the Bealach was easy

enough, and, having reached the ruined wall that here crosses the ridge,—put

up at the time when Glen Canisp was a sheep farm to prevent the sheep from

straying on to the dangerous parts of the mountain, -we called a welcome

halt for luncheon.

Half-an-hour sufficed for this and the necessary pipe,

and climbing leisurely up the slope at the western end of the col, we were

soon standing on the dome-shaped eminence that crowns the great cone of

Caisteal Liath.

Here, for the first time, we stopped to take a long

look at the magnificent prospect that lay before us. Beneath our feet, as we

looked out to the west, lay the houses of Lochinver, fringing the sheltered

bay, beyond which the wide Atlantic stretched away to where the long blue

line of the Outer Hebrides lay like a cloud along the western horizon.

On the north, the long wall of Canisp cut off much of

the view, but we could see on the left the great precipices of Quinag, and

the wide rolling expanse of hill and valley, studded with innumerable

lochans, which stretches away from the northern shores of Loch Assynt to the

low bare promontories of Stoer and Ardvar.

To the east, the sharp peak and great corrie of Ben

Dearg showed above the smooth contours of the Cromalt Hills; and farther

away, against the south-eastern horizon, rose the beautiful cones of An

Teallach in Dundonnel, the highest of the sandstone mountains.

Turning to the south, we looked across the lonely

waters of Loch Veyattie straight into the profound depths of Corrie Dubh,

that magnificent amphitheatre carved out of the northern face of Coul Môr.

Beyond the narrow winding shores of the Fionn Loch, and the line which

marked the deep valley of the Kirkaig, lay the broad expanse of Loch

Skinaskink,* dotted with wooded islets, and backed by the graceful cone of

Coul Beag and the splintered spires and pinnacles of Stack Polly. Behind

them rose the long ridges and needle-like peaks of Ben More Coigach and the

Fiddler; while far away to the south-west stretched the Rhu Coigach and the

scattered archipelago of the Summer Isles.

The atmosphere was not clear enough for a very distant

view, but beyond the faint line that showed where the Cailleach Head and

Greenstone Point stretched into the Atlantic, we could just catch the dim

outlines of the hills of Gairloch and Loch Maree.

But we had now to think about turning homewards; and

while C- sat down to make a sketch, H- and I went to prospect the farther

end of the peak, fired with the wild idea of climbing down the western face,

and thus really traversing the mountain from end to end. But after

scrambling down for some distance, we found ourselves brought up suddenly by

a sheer wall of rock plunging straight down for several hundred feet, which

effectually put an end to our hopes in that direction. So rejoining C-.----

on the top, we determined to take the first practicable gully on the north

side, and trust to chance that it would lead us to the foot of the hill.

Down we went, the loose debris clattering and sliding

under our feet, and in a very short space of time—by dint of glissading with

the stones, when practicable, and clinging to the rocky side of the cleft at

the steepest parts—found ourselves within twenty feet or so of the foot of

the cliff. Here our progress was barred by a miniature waterfall, trickling

over the nearly vertical rocks, green and shiny with moss and liverworts,

and making a very unpleasant, if not impossible, place to get down. However,

retracing our steps for a little way, we found a branch gully, which

afforded an easy path down to the foot of the precipice.

Our hard work was now over, and, rattling down the

talus slope, a rough walk of half-an-hour brought us to Glen Canisp, and

crossing the stream just above Loch-analitain Duich, we struck the forest

path at Suileag.

From this point we had a good road under our feet, and

the three miles over An Leathad to the Inver were soon accomplished.

Crossing the river at Little Assynt, we found our trap awaiting us at the

shepherd's house, whence a drive of nine miles along the shores of Loch

Assynt brought us back to Achumore about eight P.M., in good time for a very

acceptable and well-earned dinner. The distances traversed are roughly as

follows:

Inchnadamph to Loch Awe, 4 miles; Loch Awe to foot of

Meal! Bheag, 6 miles; along ridge to west end of Caisteal Liath, 1˝ mile;

from foot of Caisteal Liath to road at Little Assynt, about 5˝ miles; Little

Assynt to Inchnadamph, 10 miles—Total, 27 miles, of which 14 can be driven.

Suilven can also be reached very easily from Lochinver,

the route taken being by Glen Canisp Lodge and the forest path to Suileag.

There is no difficulty whatever in reaching the top of Caisteal Liath (the

western peak) by going up the Bealach Môr, either from the north or south

side, and it is only in crossing the gap between the eastern and middle

peaks that any real difficulty or danger is to be found.

|