|

"The Father worketh hitherto,

And Christ, whom I

would serve in love and fear,

Went not away to rest Him, but to do

What could be better done in heaven than here,

And bring to all good

cheer."

WALTER C. SMITH.

On

the thirteenth of March, 1897, Mr. Mackinnon was inducted to the First or

Highland charge of Campbeltown, as assistant and successor to the Very

Rev. J. C. Russell, D.D. At the dinner which followed the induction, Dr.

Russell remarked, in his address, that Mr. Mackinnon came to the Highland

Church of Campbeltown as the thirteenth minister since the Revolution in

1692. Whether that number was unlucky or not, he was sure that Mr.

Mackinnon, by his talents, devotion to duty and general abilities, would

compel the number to be a successful one. Seventeen years later a member

of the Highland church wrote— "Mr. Mackinnon's ministry here was one long,

glorious triumph."

On the Sunday following the induction

the services were conducted by the late Rev. Dr. Robert Blair, who told

the congregation that in their new minister they had got a splendid

general, and he did not think that, supposing they had searched broad

Scotland, they could have found a better man than his young friend Mr.

Mackinnon.

The Highland congregation of Campbeltown took the young

minister to their hearts at once, and he had a warm and enthusiastic

welcome from all classes of the community.

The

Duke of Argyll, in a most kind letter, expressed

his very great pleasure with the appointment, and wished him a successful

and happy ministry.

The Highland Church in Campbeltown

had for many years been ministered to by men of considerable distinction

and ability. Dr. Norman Macleod, of St. Columba's, had been minister there

for sixteen years, having succeeded the cultured and scholarly Dr. Smith,

of whom we read that he was the most powerful and eloquent Gaelic preacher

of his day. And as these lines are being written, a letter from

Campbeltown tells of the highly appreciated services of the venerable Dr.

Russell, ministering during the vacancy caused by the translation of the

Rev. J. M. Munro to Edinburgh: "How we did enjoy the sermons and prayers

of the good old man. He looked so well and vigorous, and many thought his

voice stronger even than in his younger days."

The

church, a massive square building, stands on an eminence facing the

bay—beautiful indeed for situation. To its quiet and peaceful surroundings

we sometimes resorted on summer afternoons.

As in

Stornoway, the forenoon service was a Gaelic one, at which the attendance

was small. But at two o'clock in the afternoon the large church as a rule

presented a spectacle sufficient to inspire any preacher. This was the

service from which Mr. Mackinnon expected greatest results, and had them.

After he was married we never left the manse without his asking that we

should kneel down together and pray that souls might be

given him for his hire. Then he preached as if his lips had been touched

with alive coal from off God's altar.

The monthly evening services begun by Mr. Mackinnon

were attended by people from all the churches and were very greatly

blessed. It was at one of these services that he preached a remarkable and

rousing sermon against raffling at church sales and bazaars. It was a

courageous thing to do, but he was absolutely fearless wherever Christian

principle was concerned his motto was, "Be ye clean, ye that bear the

vessels of the Lord"; and "his strength was as the strength of ten,

because his heart was pure." Mr. Mackinnon's sermons on Temperance were

not less remarkable. His arguments were always sound and convincing; with

infinite care he would marshal all his facts, gather together statistics

from every available source, cite judicial and medical opinion of

indisputable authority, and crown the whole with an irresistible appeal to

the highest and best in the hearts and natures of his hearers. "If you

support the cause for which I plead," he cried, on one occasion when

preaching a temperance sermon, "you will strike a blow for freedom, for

the Church, for God, and for humanity, as well as for yourselves. May each

of us have grace to say with a great poet—

"The storm-bell rings, the trumpet blows,

I know the

word and countersign;

Wherever Freedom's vanguard goes,

Where

stand or fall her friends or foes,

I know the place that should be

mine.

"Shamed be the hands

that idly fold,

And lips that woo the reeds' accord,

When laggard

time the hour has tolled

For true with false, and new with old,

To

fight the battles of the Lord."

The week-night

prayer meeting in Campbeltown was the best we have ever known. There was

always a good attendance, men and women, and young people from the Guild

and Christian Endeavour Society. The Minister could call upon any one of

his elders, deacons, or endeavourers to engage in prayer, and they were

always ready and always reverent. There was a steady glow about that

meeting throughout the whole ministry, and we take leave to say that

nothing helps a minister so much as a real live prayer meeting.

In July, 1898, the kindly Carnpbeltown people had another welcome for us

when we went down together, and if the Lowland wife had any misgivings as

to how she would be received by a Highland congregation, they swiftly

disappeared. From first to last, it was loving

kindness all the way. The ties which bind us to

dear old Campbeltown are very sacred and tender now, and we thank God we

were privileged to be there.

The wedding gift to the

Minister from his people was a beautiful gold watch and chain, which were

treasured to the last. The watch was never left lying about, and no one

was allowed to wind it up save himself. It hangs pathetically just where

he always hung it at the close of each day's work, and is still kept

going. It bears the inscription—

PRESENTED

TO THE

REV. HECTOR MACKINNON, M.A.,

MINISTER OF THE FIRST CHARGE

OF THE

PARISH OF CAMPBELTOWN

BY HIS

LOVING AND DEVOTED CONGREGATION

ON

THE OCCASION

OF

HIS MARRIAGE."

It was here, in

Campbeltown, that the golden years were lived, and we both had grown to

look back upon them with a wistful tenderness, knowing, somehow, that

nothing like them would ever come again in time. How pleasant it was to

visit together amongst all the kindly church folk! "Can you be ready at

two o'clock?" the Minister would say; "the

visiting is as easy again when you are with me." If we could only have

done more to help.

The Sunday

evening services at Drumlemble, the Pans, and Peninver were opportunities

for getting to know the country people. What kindnesses we received as we

went from house to house in town and country! And how glad the people

always were to see their minister. Sometimes in the country two or three,

or more, would be gathered together in one house and a short service held;

sometimes there were babies to be baptised, or an invalid to cheer.

With all the other ministers of the town, Mr. Mackinnon lived on terms of

genuine cordiality, and it was delightful when one and another of them

would drop into his manse, as they very often did. The ' Clerical Club "of

those days met once a month in all the manses by rotation. The ministers

gathered in the study at three o'clock on Monday afternoon for religious

conference and discussion of any particular paper which had been read by

one of them. By five o'clock the ladies had arrived, and all met together

in the dining- room for tea. These meetings were a source of much happy

fellowship. The Rev. J. A. Baird, M.A., at that time minister of Longrow

United Free Church, now of Broomhill, Glasgow, says of them :-

"I have none but pleasant memories of Mr. Mackinnon. I recall happy days

together in Campbeltown, where we were associated in

all sorts of Christian effort. The pleasant afternoons and evenings in the

Highland manse; the hospitable way in which he was wont to welcome us; his

kind and genial manner which at once put the visitors at their ease; his

hearty, ringing laugh which was so infectious; his anxiety that all should

be properly attended to, and made to feel at home. It was always a

pleasure when he paid a visit to us on these interesting occasions, when

the Clerical Club met at our house, and at other times. Mr. Mackinnon was

one of the most regular attenders at the meetings of the Club; his

contributions to the subjects under discussion were always helpful and

suggestive, and a distinct want was felt when he happened to be absent. To

be in his society for any length of time was a high privilege. One always

left feeling the better for the conversation and fellowship."

The coming of his little son was a great joy to the

Minister; all the father seemed to waken in him at once, and his deeply

affectionate nature broadened and expanded in this new relationship. The

Minister wished him called Donald; some one remarked that he was the first

boy to be born in the Highland manse since Norman Macleod, and without

troubling to verify this statement, we called him Donald Norman. And how

every one's arms seemed to open wide to the little stranger How his

aunties hovered over him, and " oh,poor wee thing, poor wee thing," just

as if his father and mother were ill-using him ! how he behaved best with

his grandfather, and how every one in the old manse, including the

Minister, if he thought no one was listening, seemed to go about crooning

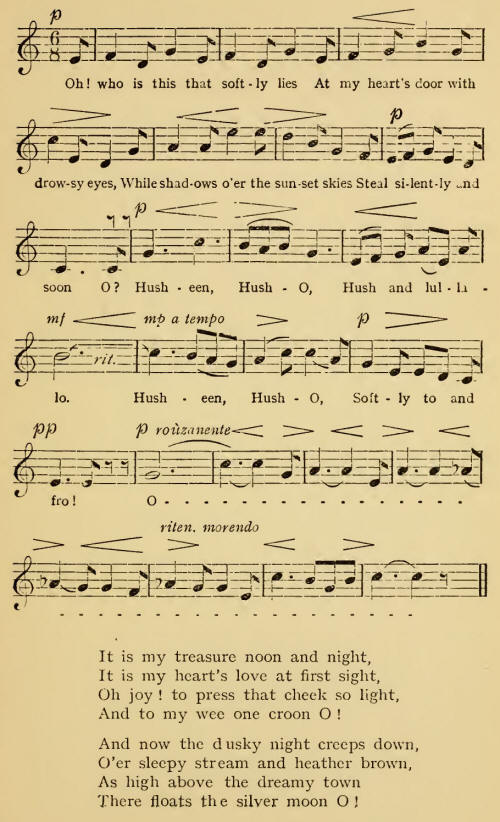

the lullaby, picked up from the aunties-

But the angel-visits to the manse of Campbeltown at this, and all its

other times of need, were those of the one whose name we speak softly in

our hearts, to whom the Minister was as her own son, and whom

"We have loved long since

And lost awhile."

Mr Mackinnon always said that never before had he been able so fully to

enter into the feelings of the fathers and mothers he visited, whose

little ones were ailing, or had been taken away. Often on returning from

the funeral of a little child, he would say, "Oh, these poor people

to-day! I thought of our boy, and of what it would mean to us if he were

taken like that."

And as the child grew, the patter of

little feet and the prattle of baby talk filled the big manse with

sunshine. And once, when we had to be away for a week or two, the Minister

remaining behind, because as he said, he could not leave his work, two or

three days in the empty house were enough—"dreich dreich"

he wrote, and came after us.

One of the numerous kindnesses we received from our Campbeltown friends

was the use of a dear little cottage, most comfortably furnished, for a

month every spring. It stood close to the water's edge, about a mile and a

half from the town, and had a garden back and front. The Minister cycled

to and fro, and the parish work went on as usual. It was a delightful

change without the fatigue and expense of travelling, and a welcome relief

to be away for a little from the incessant clanging of the manse door

bell. We used to leave the quiet cottage a little sadly sometimes; once

when we had finished shutting up, and were ready to start, one of the

children, who was just beginning to talk, kept up a half mournful

sing-song all the way as he was being wheeled home in

his perambulater—"vee cottage avay, aw blinds down." But the Minister

strongly disapproved of long absences from the manse.

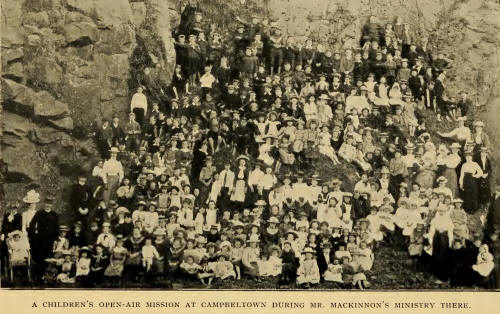

It was about this time that a special Children's

Mission was conducted in connection with the Highland Church. The

missioner was Mr. John Hutchison, temperance evangelist of the Church of

Scotland, and the meetings were conducted mostly in the open air. It is

not possible to tell how much good was done, but many, very many, parents

expressed their gratitude for the helpful teaching which their boys and

girls had received. There are people, no doubt, who think it is useless to

try to evangelise children, but Mr. Mackinnon felt strongly that the

earlier children were brought under the influence and teaching of religion

the better. The writer remembers being asked as a girl of twelve to attend

special meetings for children. The missioner was in downright earnest, and

captivated us all by his perfectly natural and unstrained talks about

religion. The early good impressions still remain, so that such efforts

must surely be worth while.

But better still we think than the open-air mission for children were Mr.

Mackinnon's own homely talks and short sermons to the little ones from the

pulpit on Sundays. One such occasion we recall when the theme was

"selfishness." In order to give point to his remarks, the preacher told

the story of the little girl who was one day out visiting with her mother,

and had two apples given her, one of which was bad. On the way home the

child was eating the good apple, when her mother said, "Mary, are you not

going to keep some for Charlie? ' "Oh yes, mother," said Mary, "I am

keeping the rotten one for Charlie!" It was a very broad smile which went

round the faces of the congregation. Mr. Mackinnon used to say lie had far

more freedom in speaking to children after he had boys of his own. And the

little fellows seemed to imitate their father in everything. One of them

would sometimes sit for a long time (as children reckon time) holding a

book, invariably upside down, under pretence of reading "like daddy." And

every Sunday, without fail, a "service" was conducted either in the

dining- room or the nursery, while the Gaelic service was proceeding in

the church. At one of these "services" Mrs. Hutchison, of Coatbridge, was

present, and as the very diminutive preacher appeared, marvellously

arrayed in an old black cassock, a pair of bands, and a large white

handkerchief folded three corner-wise to represent a hood, and took up his

position on a chair in front of a revolving book-case, he gravely opened

the proceedings by administering a very pointed rebuke to the two

ministers' wives who were "talking in church." Sometimes the "congregation

" wished to remain seated during the singings, but no such indulgences

were tolerated. The subject of the address on this particular occasion

was, "Jesus stilling the storm." It was a wild day, and we were requested

to look out at the window and observe for ourselves how the angry waves

were heaving and tossing the little boats in the bay. Then followed a very

lucid remark on the "walking on the water" "it was not like little

children wading, with their feet down through the water on to the sand, oh

no, it was like this" (here the little hands were held up and the open

palms made to pass across each other) "walking on the very top of the

water." There was absolutely no thought of questioning in the child mind—"

He who holds the waters in the hollow of His hand" was quite able to walk

on the top of them, So "trailing clouds of glory do we come from God who

is our home." May the child faith never grow dim. After another singing it

was abruptly announced, and with somewhat indecent haste we thought, that

the "collection would now be taken," and the ministers' wives found

themselves in disgrace again, but were allowed to go upstairs for their

offerings.

Nothing could have

been more pleasing than the affectionate interest the people showed in the

manse children. Picture books and toys were continually finding their way

into the nursery, and once a very indulgent young lady brought a doll—a

boy-doll in full Highland costume. He was straightway named "Onnond

Adonand "—Ronald Macdonald—and was lovingly cherished. But Daddy, in whom,

notwithstanding all his tenderness, there was much of the Puritan,

disapproved of too many toys, and especially of dolls for boys. Coming in

late one evening and observing that " Onnond" was in the cot with the

sleeping child, "These be thy gods, O Israel! he exclaimed, and in the

morning nothing was seen of Ronald Macdonald, for he had been spirited

away.

Another very indulgent

lady was one who had followed the Minister from Stornoway and taken up

residence in Campbeltown. She had been one of the most active promoters of

the Stornoway presentation, and indeed was the first to propose that it

should take the form of a pony and trap. Nothing pleased her so much as a

talk with the Minister's little boy, who was at this time between three

and four years of age. One day he was regaling the old lady with a

description of his various horses, each of which had its own name and its

own special duties to perform. He was careful to emphasise the fact that

they would not "go" unless you pulled them by a string. It was only a

"live" horse that would "go"; then with a touch of unconscious pride,

"Daddy had a live pony and trap in Stornoway 'but (in tones of real

disappointment) it was just a white elephant!" "Umph," said the listener

with a chuckle, "we'll pluck that crow with him the next time he comes."

It was as well for the Minister that she was one of his most ardent

admirers, in whose eyes "the king could do no wrong."

The Woman's Guild and the Christian Endeavour Society

in Campbeltown were each a source of much encouragement to the Minister.

None of the organisations indeed ever gave any cause for anxiety. Of the

Christian Endeavour Society, which was inaugurated by Mr. Mackinnon

himself, one of its members writes:-

"We Endeavourers still regard Mr. Mackinnon as our

spiritual father, and speak of him often at our meetings in terms of

sincere affection and esteem. It is due to his influence that the

Christian Endeavour Society of the Highland Church still exists as a

healthy, energetic organisation within the church, whereas the same

Societies of the other churches in the town, inaugurated at the same time,

have ceased to be."

The

Endeavourers were an earnest band of bright young people, and helped their

Minister in very many ways.

Mr. Mackinnon opened a class for Bible study in the church hail on Sunday

mornings at ten o'clock. This class was the means of great blessing to

large numbers of young men and women. He also taught a Bible Class, taking

the subjects set for the young Men's Guild; and one year a pupil in this

class, a lady, took first place in the examination for Scotland, gaining a

gold medal and five pounds. The other members of the class all gained

honourable distinction.

The

Woman's Guild worked steadily and quietly from year to year; the poor of

the parish were their special care ; and they annually collected from

house to house subscriptions in aid of the Women's Association for Foreign

Missions. The minister never had to beg for money from the pulpit.

Whatever was required was given quite willingly and without any ado.

It is interesting to observe that this ready generosity

has always been characteristic of the Gaelic congregation of Campbcltown.

In the Life of Dr. Macleod we read that when he became minister of

Campbeltown, the church had not been completed, and before Communion

services could be held, it was necessary to be at the expense of providing

a large tent in which to accommodate the people. An announcement to this

effect was made, and the people were at the same time informed that the

elders and others would call upon the members of the church, and would

receive from such as were willing to give subscriptions for the payment of

the tent, but that no individual was to give more than one shilling. In

the course of a few days £14 beyond the cost of the tent was subscribed.

And again, when Dr. Macleod proposed to have the

Communion celebrated twice a year instead of once, as the custom then was,

the Presbytery opposed him in this, and the heritors refused any allowance

for Communion elements. Nothing daunted, he again appealed to the people,

upon whose support he could at all times rely. Communion cups and flagons

were brought down from Glasgow and a most solemn service was held. The

separate collection which was made at the door of the church, for money to

defray the expenses incurred, was so liberal that a balance was handed

over to the Poor Fund.

And we

remember that this liberality still prevailed in Mr. Mackinnon's time;

always something over from year to year, which the people were pleased and

proud to hand to their minister at the annual social meeting. We recall,

too, how one year the Women's Association for Foreign Missions had issued

an appeal from headquarters for money which was unexpectedly required.

What could we do ? The session's work was almost over, and the annual

contributions to the funds of the Association had already been given.

Could we each do an extra piece of work and have a small sale? Then one

quietly told another, and soon it was evident that all the women of the

congregation, in town and country, were eager to have a share in sending

the Gospel to those who "sit in darkness and ignorance." We could never

forget how even the poorest came to the manse with their voluntary

offerings, and in less than six weeks there was a sum of £40 to send to

Edinburgh. It had all been done so quietly, and the Minister was gladdened

on his way, more especially as the contributions for the year following

suffered not at all.

In Campbeltown we had several special missions but

the most notable was a month's united mission for the whole town, arranged

by the ministers of the various denominations in concert. If we are not

mistaken, the idea of a united mission emanated from the "Clerical Club "

already alluded to. But it was quite impossible for Mr. Mackinnon to live

and work in other than the most friendly relations with all his brother

ministers of whatever denomination. His dear desire ever was that all

should work unitedly and harmoniously. Had he been associated in any way

with the Bishop of Zanzibar—well, "it's an ill wind that blows nobody good

"—we should probably not have heard so much of the Kikuyu Conference.

We had in Campbeltown during the mission seasons the

services of such men as the late Rev. William Hutchison, of Coatbridge;

Mr. Watt, of Powis, Aberdeen; Mr. Houston, then of Cambuslang, and Mr.

Mackenzie, now of Coatbridge. At the meetings for prayer, the afternoon

Bible readings, and the crowded general meetings, the good seed was sown

into ground which had beforehand been carefully prepared, and the

ministers had their harvest of souls garnered into the Kingdom.

There were no more welcome guests in the manse of

Campbeltown than Mr. and Mrs. Hutchison, of Coat- bridge. Once every year

latterly Mr. Hutchison was the assisting minister at the Communion ; his

sermons and addresses at these solemn seasons seemed to lift us all up and

draw our hearts and thoughts into the Unseen. We can see him yet as he

stood in the large square pulpit for the last time, his face aglow with a

light which was not of earth, and held us spellbound with the thoughts and

words of the two wayfarers on the road to Emmaus, who had unconsciously

companied with the Master—"Did not our hearts burn within us as He talked

to us by the way."

Of these

times Mrs. Hutchison writes --

"It was always a great joy to my husband to go to

Campeltown and assist Mr. Mackinnon in any way, especially at a Communion

season. My husband used to say that there was no house he stayed in where

he felt so much at home as in the manse of Campbeltown. I remember once,

while the Gaelic service was going on in the church, we had a meeting in

the manse nursery. We were told to sit very quiet by a wee mite of a

minister, who went through the whole service, then lifted up his little

hands in blessing and stepped down from the pulpit, telling us we could

'talk now as the people were all gone.' I told his father all about it

when he came in, and daddy took his wee boy in his arms, pressed him to

his heart, and carried him off to the study. Another time was when one of

the wee boys had been naughty, and would not say he was sorry, and the

minister went to church a little sad. After along time I peeped into the

nursery and found him taking some one for a drive with his brown horse and

a wooden stool. I tried to get him to say he was sorry, but he said, 'I

can't, for I don't feel it here yet,' pointing to his heart. But when his

father returned from church, he ran to him at once saying, 'Daddy, I am

sorry,' and was in his father's arms almost before the words were out.

"When Mr. Mackinnon used to come to us every one was

delighted. He was our preacher once during a special mission in Coatbridge.

In all the public works he addressed the men during their dinner hour, the

women at three o'clock in the afternoon, and then the church meeting in

the evening. The people turned out in great numbers, and many were led to

Christ through his words. He won the hearts of the people in Coatbridge,

and was more and more beloved by them as years went on. I remember once

when he preached for my husband, a doctor in the town said to me, 'I would

not have missed that sermon for £50.' He preached as if he stood between

the living and the dead. Lady Carrick Buchanan once told me how much she

had been helped by his sermon, ' The bow in the cloud.' He used to comfort

so many hearts. We were always sorry when the time came for him to return

to his dear ones. He used often to say, 'Oh, I must tell my wife that.' I

used to chaff him about his love letters, and he would laugh and say, 'My

wife's letters are all love letters.' In the home he was so thoughtful for

others and tried to avoid giving trouble. He endeared himself even to the

servants during the times he stayed with us. I remember when he and Mr.

MacFarlane attended the Bridge of Allan Convention the year my husband and

I were in charge of the Ministers' House there. They were as full of fun

and frolic as two schoolboys; I said I would have to separate them. But at

the meetings Mr. Mackinnon was so much in earnest, and was always the one

to inspire his fellows."

It

was in March, 1902, that Mr. Mackinnon's second son was born. In the midst

of a sudden and blinding snow storm, Donald Norman playing happily in his

nursery was told by his father that he had now a little brother. The big

blue eyes opened wide with wonder and the horses were all forgotten, as

with eager hurrying feet the two mounted the stairs to see the baby of the

snow, who was by this time protesting loudly against everything in

general.

Some weeks later,

both the little ones were taken to church, and the baby brother, receiving

the name of Robert Somerled, was baptised with water from the River

Jordan, kindly sent for the purpose by one of the ministers of the town,

who had just returned from Palestine. And the Carnpbeltown people will

always remember how soft and tender the Minister's face looked on these

occasions, as he kissed his little Sons and handed them back to their

mother. And the manse nursery was now a happier place than ever; for it

was not until its occupants were transferred to the manse of Shettleston

that there were "wars and rumours of wars! " The time came when we had to

redeem our promise and visit the manse of Coat- bridge, and one murky

night we found ourselves standing in the smoke and grime of a low level

station in Glasgow; into the same carriage with us was brought the infant

son of the Rev. Thomas Kearney, of the China Mission, Ichang, both babies

about the same age, and both enlivening the journey with lamentations loud

and long. Reaching the town, we found ourselves wondering when we would

get out of the smoke, and were told that here in Coatbridge there was a

perpetual "pillar of cloud by day and fire by night." How glad we were of

the warmth and hospitality of the manse on the hill amongst the trees, and

the kindly faces of its merry group. Then next day Lady Carrick Buchanan

sent for us all to go to Drumpellier, and was so kind and sweet.

The following winter was one of considerable anxiety.

The Minister's throat was giving trouble; but indeed he had been doing

much hard work joyfully and ungrudgingly in various parishes, and had

undertaken many a stormy voyage. He had barely recovered when one of the

children developed " Ophthalmia" of so persistent a nature, that for many

weary weeks it seemed as if it might not be overcome. The little eyes

could bear no ray of light, all food was refused, and it was only the

wasted form of the merry little boy that was wrapped in blankets each day,

and carried in Daddy's strong arms into the darkened study until the

sick-room could be freshened. The kindly doctor was anxious too, though he

assured us it would all come right. Then one Sunday things looked very,

very bad, and when the Minister came in after a day's work harder than

usual, we could only look at each other mutely, but dared not say what we

feared. And somehow we were on our knees by the little bed in the dark

room ; no words were uttered, but the heart of the great pitying

All-Father understood. Slowly, very slowly in the weeks that followed the

little life was given back with the sight unimpaired.

Then when the sunny days came round, what drives we had

into the country, while Daddy visited all the people, and now and again we

would come upon a pale-faced mother bending anxiously over her sick child,

and we could speak as never before with a great, understanding sympathy.

After this came a visit to Tiree in the lovely summer

days, where the little ones revelled in the temporary possession of "live"

horses which would "go." How kind all the homely island people were. And

Lady Victoria would send for the "Reverend Hector" almost every day to

consult him about one or other of the many activities in which she was

engaged. Being devoted to children, she had the Minister's boys with her

for hours on several occasions, and their father was so concerned lest

they might not behave properly; but Lady Victoria sent off a note to

reassure him, declaring that they were "splendid little fellows" and that

she had "failed absolutely to discover any traces of original sin!"

Driving along the sands next day, we met her ladyship

in the Buckboard. Amused at the frantic efforts of a little Jehu to get a

big horse to "go faster," she called out," Well, how are you getting on?"

"Oh, very well, thank you, Lady 'Atoria,' but this is just a stupid old

mare, you see, it won't go fastI " We could hear her ladyship's merry

musical laugh as we cantered along the shore.

Often, too, throughout the Campbeltown years the

Minister was cheered by the visits of his early and lifetime friend—then

of Glencoe and Arrochar. And you felt you wanted to shake the two of them,

they were so frolicsome and light-hearted. But presently, when they had

retired to the study, there would be a softened silence, and subdued

tones, for these two, whose souls were knit together, could "dwell deep"

with each other in sacred things. "As iron sharpeneth iron, so a man's

countenance sharpeneth the face of his friend."

The ministers and assistants of the various other

bodies in the town all found their way into the Highland manse ; and we

like to think that the "fellowship of kindred minds," and the always

helpful conference, have still their fragrance in many manses throughout

the country. "He was such a big man in every way," says a minister of the

United Free Church, "a giant in the ministry, and nowhere was he more

beloved than by the men in our church. We expected so much from him in

time future, as we had received so much from him in the past."

"I always associate with Mr. Mackinnon," writes another

United Free Church minister, "the idea of manliness. There was nothing

weak or small about him. He was absolutely fearless in his defence of what

appeared to him to be the truth, unsparing in his denunciations of sin and

his exposure of shams, a straight fighter and a hard hitter who did not

shun to declare the whole counsel of God. At the same time there was also

a tender note in his preaching, as he sought to set Christ before the

sinner as an all-sufficient Saviour, and pleaded with him to come and find

rest in Him. There was the clear ring of conviction in all his preaching.

One felt that he was speaking out of his own deep experience of the things

of God. That which he had seen and heard he declared unto others. Another

characteristic of Mr. Mackinnon was his broad-mindedness. Although

perfectly loyal to his own denomination, he was quick to recognise the

good in others, and was on the friendliest terms with all the neighbouring

ministers in Campbeltown. United Free Churchmen had cause to be grateful

to him for the sympathy and support he extended to them in their time of

trial. He was always ready to co-operate with any of Christ's servants to

whatever denomination they might belong. A truer friend one could not

have. He was so unselfish and unassuming, so broad in his sympathies and

so optimistic in his outlook upon life, that he drew out the esteem and

affection of all who knew him. The memory of his diligence and

faithfulness is a lasting inspiration to us."

On the walls of what we still lovingly call "the Study"

hangs an illuminated address in the following terms

"At Campbeltown,

the twenty-ninth day of March, 1905, which day the Kirk Session of the

Lorne Street Congregation of the United Free Church of Scotland met and

was constituted.

"Inter alia.

"It was cordially and unanimously agreed to, that in

view of the approaching translation of The Reverend Hector Mackinnon,

M.A., Minister of the Highland Parish Church of Campbeltown, to theParish

Church of Shettleston, the Session place on record their warm appreciation

of the kindly sympathy and help which Mr. Mackinnon, from his own pulpit

and from that of Lorne Street and elsewhere, has so opportunely rendered

to Lorne Street Congregation in their time of special difficulty and trial

as a Congregation of the United Free Church of Scotland, and that they

express their earnest prayer that his work may be as richly owned of God

in his new pastorate as it has been in his former spheres of labour.

The Clerk was instructed to have an extract of this minute signed in name

of the Session by the Moderator and himself, and suitably prepared and

presented to Mr. Mackinnon.

"J. A. BAIRD, Interim Moderator.

"CHARLES C. MAXTONE, Session Clerk."

Mr. Mackinnon was not a candidate for Shettleston

Parish Church, but had been asked by the Vacancy Committee to preach

before the congregation, who, after he had done so, were very decided in

their choice. But we had not realised what it would cost us to leave the

people of Campbeltown; and it was not to be wondered at that when the

Minister came to preach his farewell sermon, so overcome was he by his

feelings that his voice trembled, and then stopped. On the morning of our

departure the people assembled on the pier, but as the steamer moved

slowly off not a cheer was raised ; in mute silence handkerchiefs were

waved, and each one strove to look as brave as possible. But time does not

dim the tender memories of Campbeltown, and the dear old home, enshrined

as they are " in the old gold glorious radiance of the happy long ago."

The last time Mr. Mackinnon came down to preach to us,"

writes a member of the Campbeltown congregation, his text was, 'Watchman,

what of the night?' The church was packed to overflowing; his earnestness

on that occasion will long be remembered and his words ring in our ears

yet. We love our dear old church more than ever now, because it is

hallowed by memories of him."

EXTRACTS FROM THE CAMPBELTOWN SUPPLEMENTS (1902)

REVERENCE

I

hope to speak to you from the pulpit about reverence some time soon, but

there is one phase of reverence which I wish to impress upon you by

referring to it here. When you enter the church on Sunday and take your

seat in your pew to wait for the service to begin there is one duty which

you should never fail to perform. That is to bow your head in prayer and

ask God's blessing upon yourself, your fellow-worshippers, and the

minister. God's house is God's house, remember, a place hallowed by many

sacred associations in the history of a congregation, and from the moment

you enter it to that at which you take your departure your demeanour

should be that of one who is conscious that he is in the Lord's own

presence. This leads me to ask what you do when the benediction has been

pronounced. Do you forthwith pick up your hat and join in a general

stampede to the door, or do you first sit reverently down, again bowing

your head, thanking God for privilege enjoyed and blessing received, and

committing yourself to His care during the week upon which you have

entered? I have seen people enter and leave the church as if it were a

music hail or a theatre. This is surely not becoming, and what is not

becoming should not have a place in the behaviour of any member of the

Highland congregation. H. M.

RAFFLING

I had occasion

recently to make a passing reference from the pulpit on the practice of

raffling so widely prevalent at sales of work and bazaars. But this

subject calls for more than a passing reference, and I feel that I ought

to say something about it in our Supplement. To condemn raffling at sales

is not of course to condemn these sales themselves. Far from thinking that

there is anything evil in a sale of work, I venture to express the opinion

that there is no benevolent enterprise which may become a more suitable

and efficient channel of mutual goodwill among human beings than such as

is furthered when loving hearts and nimble fingers combine to make and

fashion useful articles, the proceeds of the sale of which are devoted to

upholding a deserving cause. But an enterprise good in itself may be

demoralised by its being made the cause or the occasion of practices which

are evil, and I have no hesitation in expressing my conviction that sales

of work are lamentably corrupted when countenance is lent, as is not

infrequently done by their promoters, to a method of securing funds so

utterly at variance as raffling is with the most elementary principles of

righteousness. It has been argued—and this is the only argument worth

referring to which defenders of this system have the boldness to

advance—that at benevolent sales of work raffling is utilised simply to

secure more extensive aid than could otherwise be obtained for objects

which are alike worthy and needful of support. It has thus been contended

that in this particular instance a good end justifies a questionable

means. This argument is very plausible but very shallow. Let us look into

the matter. I resolve, say, to build a church, hail, or hospital. To carry

out my resolution I need money, and money I do not possess. But I find

that there are many sympathisers with the cause I have at heart who,

although they cannot subscribe to my enterprise in hard cash, are yet

willing to contribute " in kind," articles the value of which on my

disposing of them I shall be at liberty to devote to the purpose I have in

mind. I accordingly organise a sale of work, and I get it opened with all

possible éclat. I am successful in selling a large portion of my goods.

But a considerable quantity remains which cannot be disposed of because

the prices asked are beyond the purses of those who patronise my sale. Now

what do I do? I resort to raffling as an expedient to get rid of my goods.

I furnish the people who visit my bazaar with an opportunity of taking

their chance in winning for a trifle articles which previously they were

unable or perhaps unwilling to purchase. And thus I manage to clear my

tables, or stalls, as the case may be. But I have been guilty of gambling!

There is no gainsaying the fact. In my dictionary I find raffling defined

as "a game of chance or lottery in which several persons deposit a part of

the value of a thing in consideration of the chance of becoming sole

possessor by casting dice or otherwise, the money deposited going to the

first owner of the article." And no sane person can detect any difference

between that and gambling either in spirit or in method. The whole thing

is therefore immoral, whitewash it as you please. The immorality consists

in this, thatfrom those who lose in the game I receive money for which I

give them nothing in return, and those who gain take from me goods which

they have neither bought nor earned. In no circumstances—not even at a

benevolent sale—is it honest for a man to take money for which no

equivalent has been given, or to possess an article for which he has

neither paid nor toiled. How earnestly that great prophet of

righteousness, John Ruskin, tried to impress upon the mind of a benighted

nation the principle here inculcated. It is a principle according to which

all games of chance, raffling included, are essentially dishonest. People

in general may not see this, but their blindness does not alter the fact.

It has been contended, as I have already indicated, that subscribers to a

raffle give their money for the sake of the cause, not for the sake of the

raffle, and I am not going to question that in some cases this may be

true. But what is implied in this contention and the manner in which it is

advanced is that a righteous cause sanctifies an unrighteous means; and

according to this doctrine you may trample underfoot every one of the

commandments, not only with impunity, but also without blame, provided

that in doing so you can show that you have a good end in view. You may

rob a man of his property provided you devote the same to charitable

purposes. This is the old heresy that you may sin and should sin that

grace may abound—a doctrine from which you may deduce justification for

all the sins of humanity, not excepting the treachery of Judas. You say

the end in view is deserving. 'What more deserving end, for instance,

could a man have in view than the support of his wife and family? Are you

ready to admit that this end may be legitimately compassed by exercises in

games of chance? If not, no more are you entitled to claim that

benevolence as the chief end of a sale of work justifies the use of a game

of chance to enable you or any other person to reach that end. Again, why

in the name of goodness and commonsense are the supporters of a bazaar not

permitted, or, if need be, persuaded to give their help in a

straightforward manner, without the mutual befoolment amongst parties

which resort to such a trick as raffling involves? If they are willing to

contribute a sixpence or a shilling in connection with a raffle, and that

for the sake of the enterprise in hand, why should they not contribute

either of these sums without the stimulus and excitement provided by the

raffle? As a matter of fact that stimulus is used to extract from them

that which otherwise they are unwilling to give, so that the advancement

of the plea that they are only supporting the cause while they are really

countenancing the raffle is simply one more example of "an organised

hypocrisy." It is worthy of note that if, as a private individual, one

were to engage in this practice for his own benefit it would soon find for

him a bed among thieves within one of the walled areas which the law of

the land prescribes for such characters, but because one engages in it in

conjunction with others—a congregation or association—he escapes this

visitation. And because he escapes he imagines he is free from blame. Just

as a limited liability company may commit most of the iniquities forbidden

in the decalogue without a single member of it being put under the ban of

public opinion, seeing a company is mistakenly supposed to have no

responsibility; so a number of individuals may as an association play fast

and loose with an essential principle of right, and no one says them nay.

This is one of the ways by which the devil drugs the twentieth century

moral sense with his sulphurous opiates, killing or vitiating moral

feeling. This is how he inoculates the generation that now is with the

absurd delusion that wrong may become right provided you have a laudable

end in view and provided that in reaching that end you are one of a

considerable number of individuals working together. And as Ruskin says,

"Men love to have it so." They fail to see that the devil is the devil

still, though he present himself as an angel of light, clad with the

tapestry of heaven's high chambers. One of the saddest features of

gambling practices at bazaars is that young people- often mere boys and

girls—are employed to go round and sell the tickets, and get into a

whirligig of excitement over the sums gathered and the destination of the

articles. These young people are soon to go out into the world, many of

them far from home and home influences. If a temptation to embark upon a

career of gambling comes their way, as is quite possible, even likely,

will they not find it more difficult to resist that temptation for their

having practised raffling at sales of work and thus having that method of

obtaining money associated in their minds with commendable enterprises? I

may be mistaken, because I have no statistics to go upon; but I entertain

a strong suspicion that if the first step taken in gambling on the part of

many who have thereby made shipwreck of their lives could be accurately

traced it would be found that not rarely it was taken in the shape of

interest manifested in raffling at a benevolent bazaar. Surely our young

people have enough temptation to withstand when the devil shows himself in

his darker hue without their being rendered specially liable to be

assaulted by the gilded methods of a transfigured Satan. What then can we

do to better a state of things which we must all deplore? There are two

suggestions which I venture to make. The first is, never price bazaar

articles above their market value. To do anything else is to practise

dishonesty at a crucial point and demoralise the whole proceedings. The

second is, do not make expensive articles for a sale of work. At least let

them not be too expensive for the purse of the average buyer. It is the

dear articles that occasion the raffling, as everybody knows. If men, and

women too, are not prepared to do what in them lies to bring raffling to

an end by acting upon such simple suggestions as these, then they must

follow their own course, but let them at least remember that "God will

bring every work into judgment" and that "every man must bear his own

burden." Before I close let me add that I do not anticipate that it will

be an undertaking easy of accomplishment to deal effectively with

raffling. The evil has already a tremendous hold. It is fashionable, and

the average man and woman would rather die than resist fashion. There are

few sane enough or brave enough to make a stand against that which is

fashionable. This applies even to leaders, whether in state or in church.

Many political leaders talk and talk and do little else, as if there was

little else to do, so that the legislative machinery of the country almost

stands still. Ecclesiastical leaders are little better. Few of them

consider any interests beyond those of that mighty organisation "the

church." As long as "the church" progresses as They understand progress,

whatever the means may be by which the supposed progress is realized, they

are content. "They speak smooth things and prophesy deceits." We rejoice,

however, that there are honourable exceptions both in the state and in the

church. To these men we look for leading in the holy crusade that will

cause such an evil practice as raffling to cease to the ends of the land.

A beginning should surely be made at the temple of God whence the rafflers

should be driven, with a scourge of cords if necessary.

H. M.

CHURCH SERVICES AND CLOTHES (1899)

We hear a good deal nowadays about lapsed masses, and

their existence is all too real and much to be deplored. They meet us not

only in our large cities but in our provincial towns. They have come into

being owing to a combination of causes. But one cause I believe to be the

carelessness of parents in rearing their offspring. "Like priest like

people," said the prophet. It might be added, like parents like children."

When the fathers and mothers are guilty of neglect themselves what is to

be expected of their offspring? It is only natural that they should

neglect religious ordinances. Of course difficulties will present

themselves to many who earnestly desire to do their duty in this matter.

There is, for example, the difficulty of clothes in homes where there are

large families and the bread-earner receives only low wages. Oh, these

clothes ! they are becoming the curse of our modern church life. They have

already driven from our churches many of the people for whom salvation

was, in the first instance, designed. There was a day—alas that it is

gone— when a poor woman with her mutch could enter a church with as much

comfort as a rich lady with her feathers when a boy barefooted and

bareheaded was not made to feel by word, look, or gesture on the part of

his neighbour that the two were not made of the same flesh and blood. But

nowadays everything is sacrificed to clothes. The whole structure of

society etiquette is reared upon clothes. The very rate at which Christ's

cause is to advance in the world is made by some to depend on clothes.

Surely this is a misfortune. It is of course not wrong to wear good

clothes, but the wrong comes in when either the person who has them or the

person who has them not ascribes to them an importance which does not

belong to them. What does God care about clothes? He looketh not upon the

outward appearance of a man. He looketh upon the heart, and we also should

strive to form our estimate of a person not by clothes but by character.

It is a literal fact that dress is sometimes only a cloak for snobbery and

conceit, whereas under a patched garment often beats a brave and noble

heart. And in regard to church attendance we should endeavour to stamp out

of existence the false ideas abroad in the minds of rich and poor alike

with respect to clothes. Men and women should be made to feel that they

are as welcome in church clad in thread- bare garments as they would be

though arrayed in the most gorgeous finery; and as far as boys and girls

are concerned I see no reason why they should not attend church in the

clothes in which they attend the Sabbath School. All we insist upon is

cleanliness and tidiness, and, thank God, these are cheap in the land in

which our lot has been cast.

H. M.

UNION OF THE CHURCHES

(1898)

In one of the leading

religious journals of the country, which has hitherto advocated

disestablishment, the following paragraph appeared lately:- "One evidence

of the growing friendliness of our Scottish churches is given in the

references which have been made in various Free Church Courts to the loss

sustained by the Established Church through the deaths of Dr. Caird and

Dr. John Macleod. Not so long ago these events would have been passed in

silence. But in the Free Church Commission, recently held, expression was

given to a feeling of brotherly sympathy, and this example has been

followed since in the Free Church Presbytery of Glasgow. If a

re-adjustment of things could be accomplished by mutual consent, without

having to go through the political agony of disestablishment, there would

be cause for thanksgiving." I feel grateful to this journal for such a

paragraph. The simple truth is that if ecclesiastics of all churches would

pocket their petty ambitions, and have the manliness to disown the

sentiments of wrath and jealousy to which they have often given

expression, the church question would be settled in a very short time.

"The wrath of man will not work the righteousness of God." In no

connection is this truer than in connection with the church question. We

sincerely trust that expressions of sympathy will continue to be

interchanged from time to time between our Scottish churches. We yearn for

a united ecclesiastical Scotland. The best men in all the churches are

sick tired of this wretched controversy which has often furnished an

occasion for the worst possible exercise of the worst passions of which

human beings are capable. If the churches would agree about what is

common, or at least not alien, to the spirit, if not to the letter, of the

constitutions of them all, union would soon be an accomplished fact. At

this time we owe it to the Free Church to acknowledge the Christian manner

in which her courts have made reference to our loss. And be it mentioned

that no more eloquent or sympathetic tribute to the worth of Dr. John

Macleod was given than that of his neighbour, the Rev. R. Howie of the

Free Church of Govan. We are thankful for these references and tributes,

and we pray that the time may soon come when we shall all be one.

H. M.

DUTIES OF CHURCH MEMBERS

At

this solemn season of communion it is right that church members should be

reminded of their duties towards Christ, the church, and the world, in a

manner more permanent, as I hope, in its effects than. even an address

from the pulpit. I accordingly take the liberty of stating in this

supplement some of these duties in the confidence that members of the

Highland congregation will endeavour to fulfil them:-

1.—Have before your mind a high standard of Christian

life, and act up to that standard as God gives you grace. If you are

content to remain at the low level which satisfies some of your neighbours,

you will make no progress. Remember that you have been called to be a

saint, and ponder well all that word implies. Be always a saint, and never

anything less than a saint. Let Christ Himself be your ideal. Do not act

upon the principle—which is no principle, properly speaking—of giving God

as little of your life as possible. Give Him it in its entirety. He gave

His whole life for you, and He now gives you His life in all its fullness.

2.—Be careful to read your Bible every day, and to pray

in secret. Do not read the Word of God with less interest than you read

the newspaper. God's veracity is the foundation of your faith. That

veracity finds expression in the Bible. Study the Bible therefore. "And

when thou prayest enter into thine inner chamber, and having shut thy

door, pray to thy Father which is in secret, and thy Father which seeth in

secret shall recompense thee." You can tell God things which you cannot

tell a fellow- creature. Always make a clean breast of it at His

footstool. You can have no peace otherwise.

3.—Attend church regularly. When you are absent without

a sufficient reason you deal a blow at the very existence of public

worship; you set a bad example to others; you discourage your minister;

you harm your soul. In this matter a sense of duty and not inclination

should be uppermost. It is your duty to attend church whether you feel

inclined or not. You must not let moods determine the frequency of your

church attendance. Be present every Sabbath if possible. And do not expect

to have soft and pleasing words always addressed to you. Sometimes you

need reproof more than comfort. Do not flare up in anger when your sins

are dragged by the preacher into the light of God's countenance, but

rather repent in sorrow and humility.

4.—Attend your own church. Some one has said that

roving Christians are "lean kine." It is very true. Yet there are people

who always wander from one church to another. Anything new draws them; but

nothing new or old satisfies them. We have not many wanderers connected

with the Highland congregation, but warning is necessary all the same.

Beware of forsaking the services of your church for the sake of any other

services or meetings, whatever they be. If your own church fails you,

attend a service at another; but as long as you feel that on the whole you

are getting good in your own church then stick to it. If you are getting

no good at all, you had better cut your connection, and go where you think

you can get benefit. But while you remain a member of this or any other

church bend your energies to serve it. You have a primary duty to perform

towards your own church of which no countenance or help you give to other

churches or agencies can relieve you. Of course this does not mean that

you are to do no Christian work at all outside your own congregation. It

only implies that your own church has always a prior claim. I would like

to add—Stand by the ordinary means of grace whenever there is a clash

between them and extraordinary means. For all clashes of that description

the extraordinary means are responsible. There is never any reasonableness

in the idea that ordinary means should be neglected or suspended for the

sake of extraordinary effort.

5.—Be present at the prayer meeting as often as you can the oftener the

better. We do not make attendance at the prayer meeting or any other

meeting an essential in your salvation, but we say that the best

Christians enjoy the prayer meeting, and that there is something the

matter with you unless you enjoy it. Do not come to the prayer meeting

merely to pass the time, or because you have no other place to go for a

change, so to speak; but come in an expectant frame of mind, believing

that the prayer meeting is the place of spiritual power. The prayer

meeting should always be a "previous engagement" in relation to most of

the calls made upon your time and attention on Wednesday evenings.

6.—Do some work for the cause of Christ. If asked to

become an office-bearer, accept with humility, and fulfil your duties

faithfully. If asked to teach in the Sabbath School or help the singing in

the church, consent at once, even at the cost of self-denial. Visit the

sick and the lonely according to your opportunity. Read with them, or pray

with them, or sing with them. Or, if you are not equal to any of these,

then speak sympathetically to them. You can surely do that. Be kind to

strangers who attend your church. Try and get a hold of the indifferent.

They are not far from your door. Persuade them, if possible, to come to

church. Make an appointment with them. Tell them you will be glad to call

for them if they will accompany you. Go out of your way to suit their

convenience. You may thus win their souls. Remember always that there is

work for every one to do. Do not stand idle in the market-place. "To

complain that life has no joys while there is a single creature whom we

can relieve by our bounty, assist by our counsels, or enliven by our

presence is to lament the loss of that which we possess, and is just as

reasonable as to die of thirst with the cup in our hands."

7.—Give liberally towards the church collections. That

means give as much as you can. Now just ask yourself the question whether

you are giving to the best of your ability. If you find that you are not,

then increase your contributions. Remember that "whatsoever a man soweth

that shall he also reap." Liberality of spirit on your part is food and

drink unto God. To be niggardly is to starve God out. Israel of old robbed

Him in tithes and offerings and they did not gain by it. In this

connection read Mal. iii. 7-12.

8.—Be faithful to your church. Never be a troubler of

Zion. Do not make your opinions and wishes the rules for others to follow.

Be charitable. Believe that there are other people in the church quite as

good as you and perhaps better. Give others the credit of being sincere

when they differ from you and defer to the wishes of others where no

principle is at stake. It will also do you good to remember sometimes that

the cause of God would prosper though you and I were dead and buried.

Never talk down your church. Some people have an eye

only to flaws. To hear them talk one would think their church rotten from

top to bottom. These people do their best to ruin their church. If they

mean to remain in it they should cease from croaking. Croaking within does

more harm than cursing without.

Remember that you are a member of a great national

institution—the Church of Scotland. Your being so imposes certain

responsibilities upon you. Your church has conferred untold benefit upon

past generations and it has enormous potentialities for the future. The

fact of your being amember of this institution implies, I hope, that you

set some value upon the principles upon which it is founded. Lead your

fellow-members therefore to understand that your support may be relied

upon in the day in which these principles become the objects of

depreciation or assault. Remember that the man who cannot be relied on in

one set of circumstances in which principle is at stake is but a feeble

reed to lean upon in any other set of circumstances. This, of course,

implies that you have a principle worth defending, yea, and worth making a

sacrifice for. Surely you regard the principle of establishment and

endowment for the Church of Scotland as such.

9.—Be faithful to your minister. He loves you. He is

very sensitive to indifference. Pray for him; he needs it. Always remember

that prayer in the pew makes power in the pulpit. Do not lay on your

minister heavier burdens than he can bear. One sometimes comes across

church members who would save their own skin by making the minister

responsible for lines of conduct of which they themselves are the authors.

That is contemptible. It is no doubt written, "bear ye one another's

burdens," and a minister is bound to bear the burdens of his flock, but it

is also written, " every one will bear his own burden," and in the

circumstances before us the latter words are much more applicable than the

former.

If you are ill and

wish to see your minister send for him. Do not imagine that the birds of

the air will carry him news of your illness, or that he will come to hear

of it at all unless you adopt means of letting him know.

10.—Above all, be faithful to the Lord Jesus Christ at

all times and in all circumstances. Be as interested in His business as in

your own. Stand by Him come what may. Discard and discountenance

effeminacy and cant. Never talk above your experience. Never play the

hypocrite. Never deny your Lord. Be even down in all your dealings with

others. Young men, be manly with the manliness of Christ. Young women, be

tender with His tenderness. And let young and old alike make it the

supreme end of life to honour and obey Him. He is worthy of all your

regard and all your service.

H. M.

|