|

"I will steer my rudder

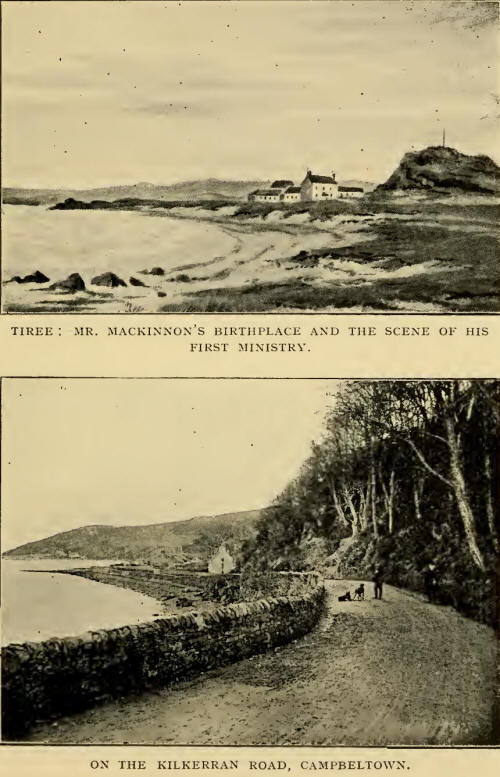

true." IN 1891 Mr. Mackinnon was licensed, and the following year was

unanimously chosen minister of his native island of Tiree, in succession

to the Rev. John Campbell. It must have been with a peculiar pleasure that

the young minister took up residence in his first manse, which is distant

from his father's house less than a mile, the church being midway between.

In the rather irksome matter of choosing furniture he had the kind

assistance of the wife of a Glasgow minister, who, not being particularly

strong, afterwards declared that there "was not another person in the

whole world she would have done it for except himself."

Scarcely had he settled down, when it became necessary to turn his

attention to church repairs. The late Duke of Argyll, the proprietor of

the island, was most sympathetic and kind towards him always, as indeed

were all the members of the ducal household. The Duke, on being consulted

with regard to the repairs on the church, replied as follows :-

"ARGYLL

LODGE, "KENSINGTON,

June 8, 1892.

"DEAR MR. MAcKINNON,

I shall be

very glad to help in your church changes—

pulpit, etc.—if you will tell me the total you contemplate

expending. I do think the congregation should help themselves a little,

and hope that you will get them to do so.

I

quite agree with you about pulpits which are straitjackets to the speaker.

"I am sure from all I have heard of you that you will

do what you can to support the ordinary moral obligations of Christianity

among the people.

"Yours very truly,

"ARGYLL."

Four months later the Duke, writing

from Inverary, says:-

"DEAR MR. MACKINN0N,

"The position you are in seems to be a hard one, and I

have had pleasure in directing that a sum of £50 be paid to you in

advance. "I am very glad to hear that you are

getting on so well. There was some risk to a 'Prophet in his own country,'

but on the other hand there are some advantages where no such prejudice

exists. So far as I am personally concerned, I am very glad to have a

native of Tiree in your position.

"Yours very

truly,

"ARGYLL."

And again in December of

the same year the Duke writes :-

"DEAR MR.

MACKINNON,- I have told Mr. Wyllie to

subscribe for me the sum of £20 towards your expenses on the church. I

hope you will be easily able to get the rest. The alterations sound very

nice. They were certainly much needed, although I judge only from the

recollection of some thirty years ago when I attended a service there. . .

. It has given me much pleasure to hear of your acceptability with the

people. "Yours very truly,

"ARGYLL."

To one with Mr. Mackinnon's intellectual abilities, and

activity of mind and body, the quiet parish of Tiree would offer small

enough scope for service. But from the very beginning he does not seem to

have allowed the grass to grow beneath his feet, seeing that during this,

the first year of his ministry, he preached at the following places, at

many of them indeed twice and three times :—Bunessan, Cornaig,* i\Ielness,

Farr, Ardnamurchan, Tobermory, Hylipol,* Baugh,* Caoles,* Vaul,* Dervaig,

Scarnish,* Ruaig,*

Balevullin,* Miltown, Morvern, Kilfinichen,

Carradale, Durness, St. Columba's (Glasgow), and Free Argyll (Glasgow).

The manse of Tiree, a large white-washed building close to the sea, and

standing out so prominently in the general flatness as to give the

impression of being "always there "—a landmark indeed to the

stranger—would offer the best of facilities to the earnest

student—quietude and immunity from interruption. From its study windows,

stretching out, out as far as the eye can reach, nothing can be seen but

the boundless rolling sea. Would it be here, we wonder now, that there

came to him the first inspiration of the "vision splendid," of which he

was afterwards to write; and, like the prisoner of Patmos, in his lonely

sea-girt isle, were there given to him also visions of the time when there

would be "no more sea"? [Those marked with an asterisk are townships of

Tiree.] He was no recluse, but visited his

people faithfully, entering into their joys and sorrows with that

largeness of sympathy which so characterised him.

"His was no ordinary common life," wrote one of these

early friends; "his great gifts, wonderful personality, and genial

big-heartedness set him apart as a man among men. To us who knew him from

his early boyhood, and who were so long and closely associated with him,

his loss indeed is very great. Outside our own immediate family circle, no

friend ever will be so deeply and truly mourned by us all as Hector

Mackinnon.

* * * * *

"This seems like a bad dream which I want to forget,"

said one whose Sunday School teacher he had been; am I never to see him

again? What a friend I have lost We mourn for him, and we are proud of

him." He had been greatly influenced by the

religious teaching of the Rev. Mr. Macfarlane, Baptist minister in Tiree,

with the members of whose family he was on terms of the closest intimacy.

The life-long friendship, unbroken and unbeclouded, which existed between

himself and one of Mr. Macfarlane's sons, now the minister of Kingussie,

is almost too sacred to be commented on. Amongst his books a little while

ago, we came across one, The Book of the Kindly Light, on the flyleaf of

which is written, "Hector, in memory of October 5-11, 1910, from D." It

was their last communion season together.

In

an interesting work entitled Outer Isles, by A. Goodrich Freer, published

in 1902, the authoress gives a graphic and true picture of some incidents

in Tiree life.

Readers will have no difficulty

in identifying the portrait so artlessly drawn, in the following extract

from the book. Describing the landing from the steamer, and commenting on

the fact that there is no pier, the writer proceeds:-

How we were to get to shore was not obvious, but we

cared little, so absorbed were we in the novelty of the scene. On the

rocks above us some fifty people at least were collected, and with much

shouting, laughing and gesticulating, two small boats, apparently already

quite full of people, were boarding our little vessel. The tiny mail boat

heaved and tossed in the water below—it seemed to us as if the very

letters would upset it, but in went the bags. The parcel post, a great

institution in the island, followed; could she possibly survive? we

wondered; and we modestly declined when courteously asked if we would care

to take our places in her, instead of waiting for the cargo boat. Being

Glasgow Fair, we were told, the boats were 'rather full.' The cargo boat

certainly was. Large baskets, like laundry travelling baskets, full of

Glasgow bread, we learned, went in first, then sundry crates for the 'Mairchant,'

then some luggage, including ours, then all our fellow-passengers; finally

half a dozen sheep. We remained modest and retiring. We knew that the

handsome young Minister who had come on board would have to get on shore

somehow, and that another boat would surely appear from somewhere. By and

by the cargo boat returned, more cargo went in, but few passengers— only

the Minister and the men who had come on board. The purser advised us to

take our seats; the kindly captain shook hands with us, obviously

perplexed as to our business there, since we were no off-shoot from the

Glasgow Fair, and we were off. We drew up at a perpendicular rock upon

which some scratches were pointed out to us as steps. Many kindly hands

were offered to help us to shore. The dog was hauled up, and we found

ourselves standing beside our luggage in a wilderness of sand, with not

the faintest idea of what to do next. Most of our companions had already

climbed into carts and disappeared, and a group of men shouting in Gaelic

over the 'cargo' at a little distance, alone remained.

"The Minister had looked at us, paused, looked again,

and with true Highland shyness walked rapidly away. It was no time for

ceremony. I ran after him, and breathlessly presented a piece of paper on

which was written the address of the house where, so we had been told, we

might hope for shelter. I had written some days before, I explained—was it

likely any one would come to meet us? The polite young Minister smiled at

our simplicity. The letter was probably in one of the bags still lying on

the rocks, or perhaps, if it arrived last mail, in the post office waiting

to be fetched; the farm in question was nine miles off, there was no road

for most of the way, there was no vehicle to be had, and being Glasgow

Fair they were 'likely full.' We began to feel anxious, not so much for

shelter on so glorious an evening as for food. Could we telegraph

anywhere? we asked, glancing at a single wire overhead. No, that only went

to the mainland; but the minister would send a message for us from the

post office, whence it would be taken with the letters, or the bread, and

meantime could we not go to the hotel? We looked around at the wilderness

of rock and sand and short, scant herbage, at the group of men still

shouting in a strange foreign tongue, at the funnel of the little Fingal

disappearing in the blue distance, at some tiny huts scarcely

distinguishable from the rocks among which they seemed to hide, at the

road' a foot deep in loose white sand, at the bare-legged boy driving a

herd of cows which clambered awkwardly among the rocks, and found the

notion of an hotel somewhat bewildering. He would go with us, this kind

young Highlander, and turning back, soon conducted us to a large

unenclosed house overlooking the harbour, where a kindly landlady, a quiet

sitting- room, a clean bedroom and a welcome tea soon made us feel that

home life in Tiree had begun."

On reading the

above, we recall at once the story of the lady who was sending her new

footman to the station to meet her soldier son returning from abroad.

Never having seen the officer, the footman inquired how he would know him.

"Oh," replied his mistress, "if you see a gentleman helping some one else,

that is he." And surely enough by this sign the stranger was identified.

The "kind young Minister" referred to by Miss Goodrich Freer was always

helping some one else. It was his joy to be doing so all his life. He was

one of God's courtiers. At crowded stations, as elsewhere, we have

frequently heard him referred to as "a treasure" by distressed

individuals, whose experiences and feelings were similar to those of the

old Scotch lady, of whom Dean Stanley tells, who had lost her luggage at

Perth station, and would not be consoled. The Dean endeavoured to assure

her that it would certainly turn up, to which she replied, "Eh, sir,

meenister, I can stand ony pairtins but pairtins wi ma luggage!"

But the young minister was not to be allowed to remain

long in his native island, for at the end of about two and a half years of

faithful service there he received a unanimous call to the parish of

Stornoway, in Lewis. That he was esteemed and loved by all his

parishioners in Tiree has ever been shown in the way in which he and his

have always been welcomed in their homes.

|