The seaboard, 35 miles in

length, which Kincardineshire possesses, is perhaps as interesting as

any other part of the Scottish coast, on account not merely of its

picturesque rock scenery but also of its historical associations. All

the way paths run close to the sea, from many points in which splendid

views can be got of maritime and inland scenery, though undoubtedly we

obtain the best idea of its beauty when sailing along the coast. Like

most of the eastern seaboard of Scotland, the Kincardineshire portion is

much exposed to the strong gales sweeping in from the North Sea; and

this, combined with the rocky nature of the greater part of the shore,

accounts for many of the shipping disasters that occur.

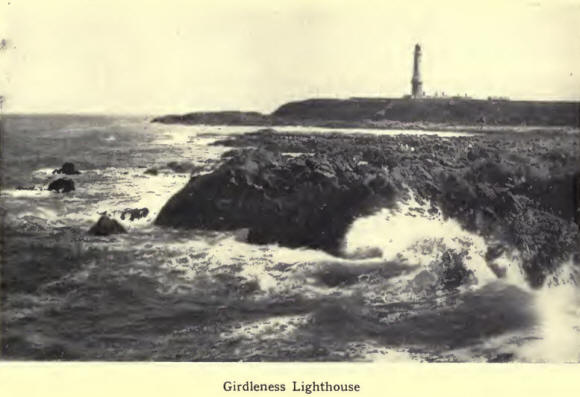

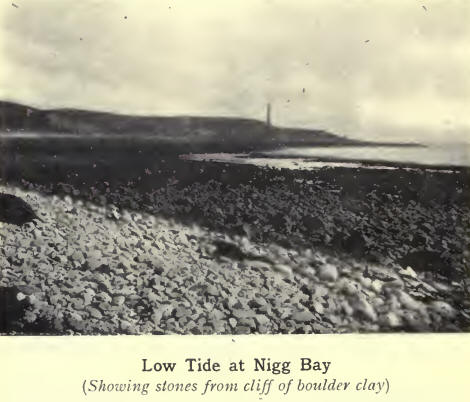

Starting our peregrination from Aberdeen we note first the Bay of Nigg,

flanked on the north by the lighthouse of Girdleness, and on the south

by Greg Ness, the circular outline of the bay being fringed by a

beautiful pebbly shore. Here, formerly, was the mouth of the Dee, which

flowed in the hollow from Craiginches. On the bay stands a fish-hatchery

with laboratory. A little inland is St Fittick’s ruined church.

Prominent on the south of the bay is a cliff of boulder clay, the rapid

erosion of which has littered the beach with thousands of stones.

Passing on, we find the

coast bold, rocky, and picturesque ; and we reach in succession the

small fishing villages of Cove and Portlethen. Between them, but back

from the cliffs, is Findon, world-famous as the original home of the

“Finnan haddock.” “The haddocks cured there,” says Thom (History of

Aberdeen), “are superior in flavour and taste to any other, which is

attributed to the nature of the turf used in smoking them.” The industry

is now entirely given up in Findon. Skateraw, a little further south,

is, like the other creeks, reached by a narrow, circuitous path down the

sea slopes, up which in former days the hardy fishermen carried in their

creels the shining “harvest of the sea” to be transported by road or

rail to the larger centres of population. Part of the fish supplies

landed here were split and sun-dried on the stony beach, and went by the

name of “speldings.” Like the “Finnan haddie,” these, when properly

cooked, were held in high esteem. The small burn of Elsick, spanned by a

substantial railway viaduct, here enters the sea.

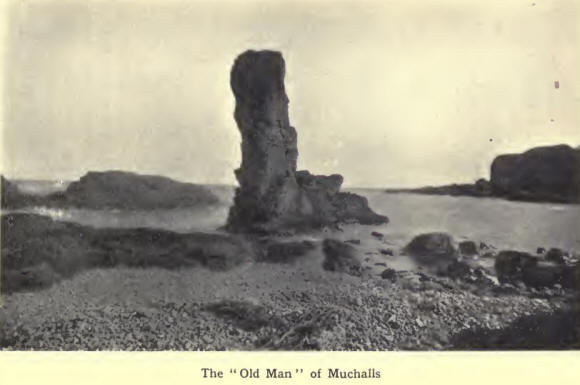

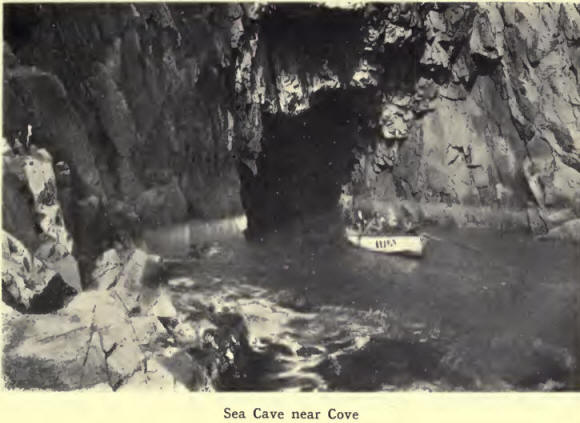

The next part of the

coast, adjacent to the neat little village of Muchalls, has received

much attention from the painter of maritime subjects, and deservedly so,

because of the artistic beauty of the rugged, weatherbeaten cliffs. Here

by the ceaseless action of the elements the softer portions of the

cliffs have been scooped out into long, deep gullies through which in

stormy mood the sea rolls with resounding and majestic grandeur. The

“Fisher’s Shore,” the “Grim Brigs” with its wonderful arches of Nature’s

own devising, the “Old Man,” and the “Scart’s Crag,” around and above

which for ever breaks the crested wave, are notable points whose names,

like that of “Gin Shore,” a little further south, are reminiscent of the

past, and full of interest and suggestion.

Between Muchalls and

Stonehaven we pass Garron Point, on whose green summit stand the

picturesque ruins of the old chapel of Cowie. The little fishing village

of Cowie nestles below the cliffs, while above, skirting the shore, is

the Stonehaven Golf Course, from which splendid views can be had of sea

and shore.

Stonehaven Bay extends in a circular sweep from Garron Point to Downie

Point. Alongside of its pebbly beach runs a promenade, flanked on the

north by extensive recreation grounds. Its waters give ample scope for

bathing and boating, while the dull grey and brown outlines of the Old

Town dwellings at the southern end impart an old-world appearance to the

scene.

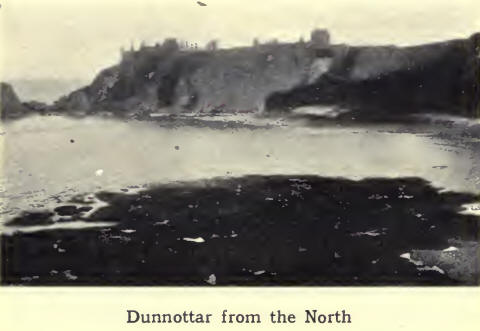

Rounding the Black Hill,

from the top of which unrolls one of the finest views of town, coast and

inland, we reach the historic castle of Dunnottar, where, as Carlyle’s

eulogy of the famous Marshal Keith reminds us, “The hoarse sea winds and

caverns sing vague requiems to his honourable line and him.” Here the

panorama formed by cliffs and bay is magnificent—the former almost 170

ft. high with cathedral-like arches, the latter with gloomy creeks and

caverns. The very names, as “Brun Cheek,” “Maiden Ivaim,” “Long

Gallery,” “Wine Cove,” testify to Nature’s handiwork and skill. South of

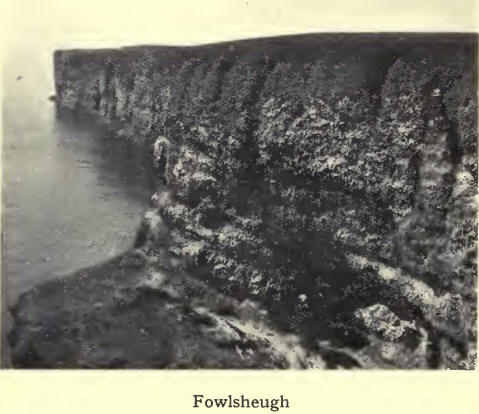

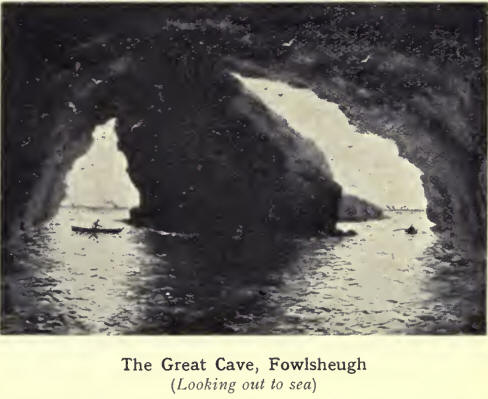

Trelung Ness we reach the highest of the rocks, the cliffs of Fowlsheugh,

the noted nursery for sea birds, extending over a mile. The birds make

their nests in the crevices of the conglomerate rock, out of which by

constant weathering pebbles have been forced, affording a natural

nesting-place. The spectacle of the myriads of birds in early summer, on

“the dreadful summit of the cliff That beetles o’er his base into the

sea,” is most interesting and instructive, and will well repay a visit

from others than bird-lovers.

Between Fowlsheugh Point

and Bervie Bay the cliffs are still bold and precipitous, with generally

no beach between their base and the deep .water. Todhead lighthouse

stands on a prominent headland at the southern extremity of Braidon Bay,

a little beyond the old fashioned fishing village of Catterline. Craig

David, a few miles further south, overlooking Bervie Bay, marks the

terminus of the high cliffs which form the natural’wall of protection to

most of the Kincardineshire coast.

From this point onwards the configuration of the coast-line is entirely

different. The beach is now low, pebble-strewn, and gravelly, with low,

shelving rocks jutting out to the sea. Gourdon—dominated by Gourdon

Hill, a noted landmark for seamen—and Johnshaven have both small

harbours, their appearance from above being quaint and picturesque. A

little further south is the hamlet of Milton of Mathers. Rounding a bend

in the coast we pass the Ivaim of Mathers, and reach St Cyrus braes,

varying in height from 50 to 300 ft. On the summit stands conspicuous

the parish church with its lofty spire. Passing over a flat beach of

fine sand bound together by sea grasses and other marine plants, we end

our perambulation of the coast at the mouth of the North Esk.

The coast-line of the

county bears witness to the gigantic power of marine erosion. Cliffs and

bays, caves and half-tide stacks, show that the action of the sea in

sculpturing coastal scenery is everywhere guided by rock-composition and

structure. In this connection we may quote the words of Sir Charles

Lyell with regard to a case of historic interest. “ On the coast » of

Kincardineshire an. illustration was afforded, at the close of last

century [the eighteenth], of the effect of promontories in protecting a

line of low-shore. The village of Mathers, two miles south of Johnshaven,

was built on an ancient shingle beach, protected by a projecting ledge

of limestone rock. This was quarried for lime to such an extent that the

sea broke through, and in 1795 carried away the whole village in one

night, and penetrated 150 yards inland, where it has maintained its

ground ever since, the new village having been built further inland on

the new shore.”

In late glacial and

post-glacial times there took place alterations in the relative level of

land and sea. The raised beaches of the coast and the alluvial tracts of

the river valleys were formed when the land stood relatively lower than

at present. Two sets of beaches are clearly marked in Kincardineshire.

Both are well seen at Stonehaven, the newer part of which is built on

the flat of the 100-ft. beach, the older on the 25-ft. beach. The lower

beach shows its best development southwards from Bervie, the old

sea-cliff forming a strong feature all the way to the mouth of the North

Esk, and the flat rocky foreshore of the present sea margin offering a

striking contrast to the frowning cliffs which bound the shore from

Bervie to Stonehaven harbour. That the land at one period stood, higher

(or the sea lower) than at present is shown by the occurrence of a

buried forest beneath the 25-ft. beach.

|