|

James Bruce of Kinnaird, the Abyssinian traveller,

was born on the 14th December, 1730, at Kinnaird, in the county of

Stirling, and was eldest son of David Bruce of Kinnaird, by Marion,

daughter of James Graham of Airth, Judge of the High Court of Admiralty

in Scotland. At the age of eight years, Bruce, who was then rather of a

weakly habit and gentle disposition, though afterwards remarkable for

robustness of body and boldness of mind, was sent to London to the care

of an uncle. Here he remained until he had attained his twelfth year,

when he was removed to Harrow, where he won the esteem of his

instructors by his amiable temper and extraordinary aptitude for

learning. In 1747 he returned to Kinnaird, with the reputation of a

first-rate scholar. It having been determined he should prepare himself

for the Bar, he, for that purpose, attended the usual classes in the

University of Edinburgh ; but finding legal pursuits not suited to his

disposition, it was resolved that he should proceed to India. With this

intention he went to London in 1753; but while waiting for permission

from the East India Company to settle there as a free trader, he became

acquainted with Adriana Allan, the daughter of a deceased wine-merchant,

whom he married, and abandoning the idea of India, embarked in the

excellent business left by his father-in-law. The death of his wife,

however, which took place, soon after their marriage, at Paris, whither

he had taken her for the recovery of her health, again altered Bruce's

destiny. Deeply affected by her loss, he first devolved the cares of his

business on his partner, and soon afterwards withdrew from the concern

altogether.

Some time subsequent to these occurrences, Bruce had become acquainted

with Lord Halifax, who suggested to him that his talents might be

successfully exerted in making discoveries in Africa; and, to give him

every facility, his Lordship proposed to appoint him consul at Algiers.

He repaired to his post in 1763, where he employed himself a year in the

study of the Oriental languages; and this appointment was the first step

to the discovery of the source of the Nile.

As our

readers must be familiar with the perilous adventures of this traveller,

as depicted by himself in one of the most entertaining works in our

language, it would be altogether idle to attempt any abridgement of

them. After many hair-breadth escapes, and overcoming many difficulties

both by sea and land, Bruce returned in safety to Marseilles in March,

1773, and was received with marked consideration at the French court.

On his arrival in Great Britain he had an audience of George the Third,

to whom he presented drawings of Palmyra, Baalbec, and other cities,

with which he had promised to furnish his Majesty previous to his

departure. It had been insinuated that Mr. Bruce was an indifferent

draughtsman, and that the drawings which he had brought home were not

done by himself, but by the artist he had taken along with him. This

charge was perfectly untrue, although it derived some countenance from

his declining to comply with a request of the King, that he should draw

Kew. When he had submitted the above-mentioned draughts, his Majesty

said, "Very well, very well, Bruce; the colours are fine, very fine—you

must make me one—yes; you must make me one of Kew! " Bruce evaded

compliance by saying, "I would with the greatest pleasure obey your

Majesty, but here I cannot get such colours."

It was

not until seventeen years after his return to Europe, that he gave that

work to the world which has perpetuated his name. It appeared in 1790,

and consisted of four large quarto volumes, besides a volume of

drawings, and was entitled, " Travels to Discover the Source of the

Nile, in the years 1768-69-70-71 -72-73. By James Bruce of Kinnaird,

Esq., F.B.S."

The long interval that elapsed between

the period of his return and the publication of his travels, had induced

many people to pretend that he had nothing worth while communicating to

the world. This malicious report was mentioned to him by a friend. He

replied, "James, let them say, as my maternal grand-aunt said. You

have," continued he, "no doubt seen that inscription upon Airth—are you

acquainted with its origin?"—"No," was the rejoinder. "Then," said he,

"I'll tell you. My grand-uncle was amongst others a great sufferer

during the Usurpation, and, owing to his adherence to the Stuarts, was

obliged to fly to Sweden. His wife, by her judicious management, and by

carrying on a small trade in the coal line, made a considerable fortune,

and built the wing of the house at Airth, now standing. Some evil-minded

persons chose to insinuate that she had acquired this fortune in a way

not very creditable to her chastity. Treating this slander with the

contempt it merited, she, with conscious innocence, caused the

inscription of ' Let them say,' to be placed over the door."

The singular incidents detailed in these Travels—the habits of life

there described, so totally unlike anything previously known in Europe

—and the style of romantic adventure which characterised the work— led

many persons to distrust its authenticity, and even to doubt whether its

author ever had been in Abyssinia at all. Those doubts found their way

into the critical journals of the day, but the proud spirit of Bruce

disdained to make any reply. The amusing " Adventures of Baron

Munchausen" were written purposely in ridicule of him, and were received

by the public as a just satire on his work. To his daughter alone he

opened his heart on this vexatious subject; and to her he often said,

"The world is strangely mistaken in my character, by supposing that I

would condescend to write a romance for its amusement. I shall not live

to witness it; but you probably will see the truth of all I have written

completely and decisively confirmed."

So it has

happened. Becent travellers have established the authenticity of Bruce

beyond cavil or dispute. Dr. Clark, in particular, states, in the sixth

volume of his Travels, that he and some other men of science, when at

Cairo, examined an ancient Abyssinian priest—who perfectly recollected

Bruce at the court of Gondar—on various disputed passages of the work,

which were confirmed even in the most minute particular; and he

concludes this curious investigation by observing, that he scarcely

believes any other book of travels could have stood such a test. Sir

David Baird, while commanding the British troops embarked on the Bed

Sea, publicly declared that the safety of the arm3' was mainly owing to

the accuracy of Mr. Bruce's chart of that sea, which some of the critics

of the day ventured to insinuate he had never visited. On this subject

Bruce is strikingly corroborated by that well-known traveller,

Lieutenant Burnes. In a letter written from the Bed Sea, so lately as

1835, he says—"I cannot quit Bruce without mentioning a fact which I

have gathered here, and which ought to be known far and wide in justice

to the memory of a great and injured man, whose deeds I admired when a

boy, and whose book is a true romance. Lord Valentia calls Bruce's

voyage to the Ked Sea an episodical fiction, because he is wrong iu the

latitude of an island called 'Macowar,' which Bruce says he had visited.

Now this sea has been surveyed for the first time, and there are two

islands called 'Macowar;' the one in latitude 23° 50', visited by Bruce,

and the other in latitude 20° 45', visited by Valentia ! Only think of

this vindication of Bruce's memory! Major Head knew it not wheu he wrote

his Life, and it is worth a thousand pages of defence."

The following rather amusing anecdote is told of Bruce :—It is said that

once, when on a visit to a relative in East-Lothian, a person present

observed it was "impossible" that the natives of Abyssinia could eat raw

meat. Bruce very quietly left the room, and shortly afterwards returned

from the kitchen with a raw beef-steak, peppered and salted in the

Abyssinian fashion. "You will be pleased to eat this," he said, "or

fight me." The gentleman preferred the former alternative, and with no

good grace contrived to swallow the proffered delicacy. When he had

finished, Bruce calmly observed, "Now, sir, you will never again say it

is impossible."

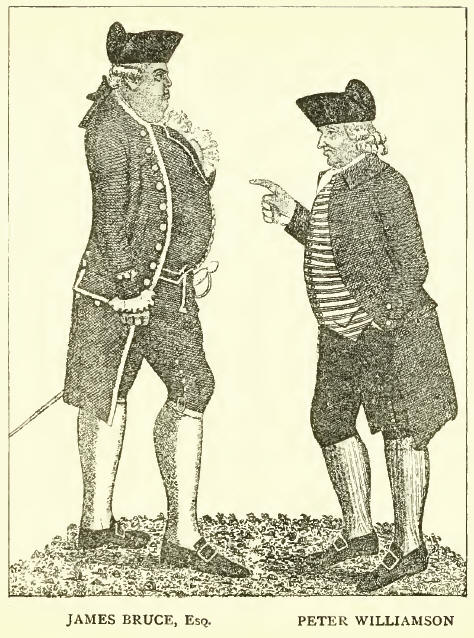

Bruce was a man of uncommonly large

stature, six feet four inches, and latterly very corpulent. With a

turban on his head, and a long staff in his hand, he usually travelled

about his grounds; and his gigantic figure in these excursions is still

remembered in the neighbourhood. On the 20th of May, 1776, he took as

his second wife, Mary, daughter of Thomas Dundas of Fingask, by Lady

Janet Mait-land, daughter of Charles sixth Earl of Lauderdale.

On the 26th of April, 1794, after entertaining a large party to dinner,

as he was hurrying to assist a lady to her carriage, his foot slipped,

and he fell headlong from the sixth or seventh step of the large

staircase to the lobby. He was taken up in a state of insensibility,

though without any visible contusion, and died early next morning, in

the sixty-fourth year of his age.

Thus he who had

undergone such dangers, and was placed often in such imminent peril,

lost his life by an accidental fall. He left, by his second marriage, a

son and a daughter. His son succeeded him in his paternal estate, and

died in 1810, leaving an only daughter, who married Charles Cumming of

Roseilse, a younger son of the family of Altyre, who assumed the name of

Bruce, and in 1837 was member of Parliament for the Inverness district

of burghs. His daughter, who survived him many years, became the wife of

John Jardine, Esq., advocate, sheriff of Boss and Cromarty.

Bruce took with him in his travels a telescope so large that it required

six men to carry it. He assigned the following reason to a friend by

whom the anecdote was communicated:—"That, exclusive of its utility, it

inspired the nations through which he passed with great awe, as they

thought he had some immediate connection with Heaven, and they paid more

attention to it than they did to himself." |