Jamie Duff was long conspicuous upon the streets

of Edinburgh as a person of weak intellects, and of many grotesque

peculiarities. He was the child of a poor widow who dwelt in the Cowgate,

and was chiefly indebted for subsistence to the charity of those who

were amused by his odd but harmless manners. This poor creature had a

passion for attending funerals, and no solemnity of that kind could take

place in the city without being graced by his presence. He usually took

his place in front of the saulies or ushers, or, if they were wanting,

at the head of the ordinary company; thus forming a kind of practical

burlesque upon the whole ceremony, the toleration of which it is now

difficult to account for. To Jamie himself, it must be allowed, it was

as serious a matter as to any of the parties more immediately concerned.

He was most scrupulous both as to costume and countenance, never

appearing without crape, cravat, and weepers, and a look of downcast woe

in the highest degree edifying. It is true the weepers were but of

paper, and the cravat, as well as the general attire, in no very fair

condition. He had all the merit, nevertheless, of good intention, which

he displayed more particularly on the occurrence of funerals of unusual

dignity, by going previously to a most respectable hatter, and getting

his hat newly tinctured with the dye of sorrow, and the crape arranged

so as to hang a little lower down his back.

By keeping a sharp

look-out after prospective funerals, Jamie succeeded in securing nearly

all the enjoyment which the mortality of the city was capable of

affording. It nevertheless chanced that one of some consequence escaped

his vigilance. He was standing at the well drawing water, when lo ! a

funeral procession, and a very stately one, appeared. What was to be

done? He was wholly unprepared: he had neither crape nor weepers, and

there was now no time to assume them; and moreover, and worse than all

this, he was encumbered with a pair of "stotvps!" It was a trying case;

but Jamie's enthusiasm in the good cause overcame all difficulties. He

stepped out, took his usual place in advance of the company, stoups and

all, and, with one of these graceful appendages in each hand, moved on

as chief usher of the procession. The funeral party did not proceed in

the direction of any of the usual places of interment. It left the town

: this was odd! It held on its way: odder still! Mile after mile passed

away, and still there was no appearance of a consummation. On and on the

procession went, but Jamie, however surprised he might be at the unusual

circumstance, manfully kept his post, and with indefatigable

perseverance continued to lead on. In short, the procession never baited

till it reached the seaside at Queensferry, a distance of about nine

miles, where the party composing it embarked, coffin and all, leaving

the poor fool on the shore, gazing after them with a most ludicrous

stare of disappointment and amazement. Such a thing had never occurred

to him before in the whole course of his experience.

Jamie's

attendance at funerals, however, though unquestionably proceeding from a

pure and disinterested passion for such ceremonies, was also a source of

considerable emolument to him, as his spontaneous services were as

regularly paid for as those of the hired officials; a douceur of a

shilling, or half-a-crown being generally given on such occasions.

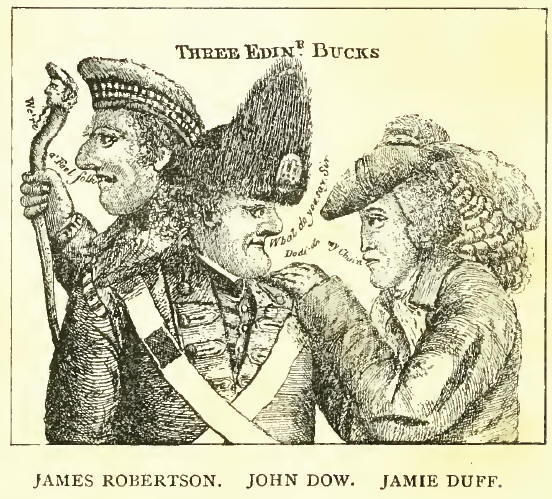

We

come now to view the subject of our memoir as a civic dignitary —as

Bailie Duff—a title which was given him by his contemporaries, and which

posterity has recognized. The history of his elevation is short and

simple. Jamie was smitten with the ambition of becoming a magistrate ;

and at once, to realise his own notions on this subject, and to

establish his claims to the envied dignity in the eyes of others, he

procured and wore a brass medal and chain, in imitation of the gold

insignia worn by the city magistrates, and completed his equipment by

mounting a wig and cocked hat. Jamie now became a vert-table bailie; and

his claims to the high honour—it gives us pleasure to record the

fact—were cheerfully acknowledged.

At one period of the Bailie's

magisterial career, however, bis pretensions certainly were disputed by

one individual; and by whom does the reader imagine ? Why, by a genuine

dignitary of corresponding rank—a member of the Town Council! This

person was dreadfully shocked at this profanation of things sacred, and

he ordered his brother magistrate, Duff, to be deprived of his insignia,

which was accordingly done. City politics running high at this time,

this odd, and it may be added absurd, exercise of power, was

unmercifully satirized by the local poets and painters of the day.

It

may not be without interest to know that this poor innocent manifested

much filial affection. To his mother he was ever kind and attentive, and

so anxious for her comfort, that he would consume none of the edibles he

collected till he had carried them home, and allowed her an opportunity

of partaking of them. So rigid was he in his adherence to this laudable

rule, that he made no distinction between solids and fluids, but

insisted on having all deposited in his pocket.

The Bailie at one

period conceived a great aversion to silver money, from a fear of being

enlisted ; and in order to make sure of escaping this danger, having no

thirst whatever for military glory, he steadily refused all silver coin;

when his mother, discovering that his excessive caution in this matter

had a serious effect on her casual income, got bis nephew, a boy, to

accompany him in the character of receiver-general and purse-bearer; and

by the institution of this officer, the difficulty was got over, and the

Bailie relieved from all apprehension of enlistment.

He was tall and

robust, with a shrinking, shambling gait, and usually wore his stockings

hanging loose about his heels, as will be shown by a full-length

portrait of him done by Kay at an after period. He never could speak

distinctly, though, it was remarked, that, when irritated, he could make

a shift to swear. He died in 1788.