"The beautiful Isles of Greece

Full many a bard has sung:

The Isles I love best lie far in the West,

Where

men speak the Gaelic tongue.

"Let them sing of the sunny South,

Where the blue Agean smiles,

But give to me the Scottish sea,

That breaks round the Western Isles!

"Lovest thou mountains

great,

Peaks to the clouds that soar,

Corrie and fell where eagles dwell,

And cataracts dash evermore?

"Lovest thou green grassy

glades,

By the sunshine

sweetly kist,

Murmuring waves, and echoing caves?

Then go to the Isle of Mist! "—Sherrif Nicholson.

The Mull of Cantyre - Campbelton—The Scot-Dalriads -

Kil-Keima - Churches of early Saints—St Colomba in Cantyre at

Kil-Colni-Keil--The Ocean—Cantyre's Dairy Farms—The Monastery of Saddefl—Legend

of Dunaverty—Kil-Cousland - St. Couslan's Weddings —Kil-Kerran - St Coivin's

Divorces—Macnahanish Bay—Kelp-Burners.

IT was on a lovely morning in the early spring that we

started for the West Coast, without any very definite intention as to where

we might drift. Our only plan was to spend some quiet weeks in the most

out-of-the-world place we could find; one where my pencil might keep me

busy, while my brother could rejoice in perfect idleness after a course of

hard reading; and what spot more suitable than the Land's End of Scotland,

the dear bluff old Mull of Cantyre, which had already given us so many

pleasant days t--that strange peninsula, in form like an outstretched

finger, about forty miles in length, by an average of six in width,

extending from the south of Argyleshire, as a mighty breakwater, for the

protection of the mainland from the sweeping of Atlantic storms.

So we started, but without reference to our

neighbours, and soon found to our cost that they were keeping holy-day, or

holiday, as the case might be. It was a Sacramental Fast--very solemn to one

section of the community, but a very "fast" day to the majority. Thus it

came to pass that every station was crowded, and the line blocked with extra

trains, and hours before we reached Greenock, our steamer had quietly sailed

down the Clyde. So far as we were concerned, we had good reason to rejoice

in the delay, as it enabled us to test the unfailing hospitality of one of

our truest and oldest friends,—but I fear that to some of our

fellow-travellers, the delay must have proved a serious inconvenience.

The third morning found us under way, and by midday we

were watching the changing lights on the Isle of Arran, or Ar-rinn"the land

of sharp pinnacles" most rightly named. Dark shadows were drifting over the

granite peaks of Goatfell, and those of Ben Ghoil, the "mountain of the

wind," which seemed to tower so high above the mist, though their actual

height is only about 2,875 feet.

Here and there were little clusters of tiny brown

huts, nestling in the shadow of the great hills, and human beings with

collie dogs and flocks of sheep moved to and fro, like atoms scarcely

visible.

As we passed gloomy Loch Ranza, with its dark

encircling mountains and old ruined castle (once a royal hunting-seat), our

attention was called to the boats of the oyster-dredgers; and we marvelled

whether the oysters of Loch Ranza have the same ear for music as their

brethren in the Firth of Forth, who require a continuous dredging-song to

lull them to their doom, so that the wily fishers must perforce keep up an

incessant monotonous chaunt, in which all their conversation must be carried

on. Various collectors of old ballads have from time to time gone out for a

night with the dredgers, hoping to add new songs to their store, but all

agree in saying that the same words never occur twice unchanged; and so they

only gain the bitter cold of a night in an open boat in one of the months

"with an B.," which you perceive excludes all the bonnie summer nights. One

allusion to this graceful fancy is found in a charming ballad which begins

The herring loves the merry moonlight,

The

mackerel loves the wind,

But the oyster loves the dredging song,

For

he comes of a gentle kind."

Several prominent head-lands were pointed out to me,

in the course of the day, as the sites of so-called Vitrified Forts—strange

relics of the past, concerning which nothing is known certainly. Among the

many theories which have been propounded, none has for me ouch fascination

as that which assumes them to have originally been Fire-Temples, the altars

of Bel, the Celtic Baal, or Sun-god.

These vitrified circular masses are generally placed

on some commanding height, often too near together to have been used as

beacon lights. The stones are fused into glassy masses, the inside more

perfectly vitrified than the outside, as would naturally be the case, if

these raging fiery furnaces were the altars, where fire burnt day and night,

and where animals and perhaps human sacrifices were offered, at the great

Baal festivals. We know that long after Christianity was introduced in

Britain, the fire-worship was continued; the land remaining in a strange

twilight state, halting between two opinions—the grossness of heathen

darkness, mitigated indeed by Christianity, but still very far from the

light of perfect day; the people in general, having some leaning to the new

faith, but a strong hold on the old idolatries.

The golden sunset fell on Ailsa Craig, and the bold

headland of Davaar, as we entered the fine land-locked harbour of

Campbelton, wherein lay many fishing-boats of all sizes, with rich brown

sails. I bethought me of old Pennant's account of this crowded harbour,

where in the last century so many as two hundred and sixty "busses" might be

seen at once. I fear that the Cockney mind, picturing a 'bus of the present

day, would be somewhat disappointed to find so very dull a little town.

Campbelton is chiefly

remarkable for the amazing fact that it is the means of annually

contributing more than one million sterling to the Inland Revenue, in form,

of whisky duty. That is to say, the distilleries of Campbelton and its

immediate neighbourhood collectively produce upwards of 2,657,000 gallons

per annum, and whisky-duty is ten shillings per gallon. Of the great sum

thus represented £705,560 was actually paid to the Collector of Inland

Revenue at Campbelton in the year ending March 1883. The surplus, being

shipped under bond, is not included in the local payments. However, whether

exported to Glasgow or elsewhere, Campbelton is responsible for the

manufacture of this enormous amount of Fire-Water! What a field for the

beneficent Blue Ribbon Army, and how justly might they plead that this vast

amount of barley should go to feed the thousands, now on the verge of

starvation, throughout our own North-West.

The whiskies of Campbelton, like those of Lagavulin

and Taiisker (which are two celebrated distilleries on Islay and Skye), have

at least the merit of being accounted first-class; and the distillers give

so good a price for barley that there is no longer any inducement for the

Highlanders to deal with the smugglers, who in very recent times had stills

for mountain-dew, all over this part of the country—so extensive a seaboard

affording good scope for their trade. The Hebrideans crossed from the Isles,

to Rhunahourine (the Heron's Point), thence marching across the hills to

Skipness in bands of thirty or forty armed men, whose rough shelties were

laden with heavy creels containing the moonlight produce, which was then

sent to Glasgow.

The "stream in the moonlight which kings dinna ken"

has not, however, wholly ceased to flow, and I have heard of sundry

mysterious presents of kegs of "the crathur," very superior in quality to

any that is to be procured from the large stills. And although the men of

Skye seem to have given up this illicit business, there are still many quiet

nooks in the dark glens of Western Ross, where it is carried on in secrecy

and comparative safety, in snug caves, or deep hollows, near some rippling

stream.

Many such romantic spots, long since deserted, do I

know in the wilds of Banffshire, where, in the heart of the dark fir woods,

amid richest purple heather, you may note in one place a circle of white

stemmed birches, in another a fringe of golden broom and tangled wild roses

clustering round a deep circular cup, where once the stills, worms and

mash-tubs were concealed, and the mountain dew was distilled, but where now

the greenest and richest ferns nestle in the cool shade, while wood-doves

murmur on every side—pleasant play-grounds for children on bright summer

days.

Old songs are not yet forgotten, whose gleeful point

lay in telling how "The Deil ran awa' wi' the exciseman," and that official

is still an unwelcome visitor in certain remote corners of the land; but the

days are gone by, when the wild Skipness men thought it all fair play to

fight their battles with a revenue cutter, and, having overpowered her crew,

to turn them all adrift again, without oars or tackle, to be tossed at the

mercy of the waves!

To return to Campbelton, or as it was anciently

called, Dairuadhem. Remote as it now seems to us, there was a time when it

was the centre of Scottish life, and for upwards of three centuries it was,

in fact, the capital of Scotland. This continued till the reign of Kenneth

II., King of the Scots, who, having finally subdued the Picts, and merged

both races in one kingdom, selected Forteviot, in Perthshire, as a more

suitable capital.

These Dairiads seem to have come over from Ireland

about the year 502 A.D., and to have founded that kingdom known in Scottish

history as Alba; their power and numbers must have increased rapidly, for

not long afterwards, we hear how the King of Alba invaded Ireland and fought

the great battle of Moyra, famous in old song. In fact, these Scot,-Dalriads

held their place as a strong Celtic race, till the Norsemen overran the

land, and moulded existing institutions to suit their own convenience. In

later days James IV. here held a Parliament, as "Parliament Close" still

attests. There were, however, certain turbulent chiefs who would by no means

render obedience to his laws; more especially one Macdonald, whose castle of

Cean Loch stood on the very spot now occupied by the large Castle-hill

Church. In order to keep this man in check, James V. came here in person,

and repaired the old fort of KilKerran, leaving in it such a garrison as

might overawe all rebellious subjects. But before the King had got clear of

the harbour, Macdonald sallied out of his castle, took possession of the

fortalice, and, in the sight of the King, hanged the new governor from the

walls.

This old castle of Kil-Kerran stood about a mile from

Campbelton. A very large old burial-ground, close by, still marks the spot

where St. Kieran, the Apostle of Cantyre, first taught the people. The cave

in which he lived, the Cove a Kieran, lies among the rocks so close to the

sea, that you cannot enter it at high water. At all times it is a difficult,

slippery scramble. Once there, you find a fine cave, with a dripping well,

filling with clear, sparkling water a rock basin, whence the Saint drank.

And beside it, on a great stone, is a rudely-sculptured cross, where, in the

solitude of this grand wild temple, guarded from all human intruders by that

barrier of mighty waters, he might worship his God undisturbed. Of his

church, once the most important in Cantyre, little, if any, trace now

remains; but two shafts of broken crosses, carved with galleys, figures and

arabesques, are among the very ancient stones in the old kirkyard.

While speaking of saintly names associated with this

town, I cannot forbear to remind you of one, the mention of whose birthplace

cannot fail to recall to multitudes (and assuredly to every Scotchman, of

whatever denomination) the name of the great, and good, and genial Norman

Macleod--a teacher as influential and beloved, and one as unsparing of his

work, as the mightiest of those Celtic Fathers; one who needs no

canonization at the hands of earthly Councils to rivet his hold on the

affections, and his influence on the life, of multitudes, even of those who

were never privileged to hear his voice, but who, nevertheless, were

followed to the uttermost ends of the earth by his good and loving words—so

tender, and yet so strong and invigorating—learning from him year by year

something of deeper reverence for things human and divine, and perchance

catching from his large-hearted liberality, something of a broader and more

glowing charity, such as would fain enfold the whole great world in its own

boundless love. Truly, were it only for having given birth to one such son

as he, Cantyre may henceforth claim to be not least among the provinces of

Scotland.

In the market-place of Campbelton there stands a very

fine cross of hard blue whinstone, covered with well-carved figures,

foliage, and runic knots, and bearing an inscription,—but whether this is

Saxon or Lombardic is still disputed. It is supposed to have been brought

over from Iona, where at one time there stood 360 stone crosses. These, the

Synod of Argyle, in A.D. 1560, pronounced to be "monuments of idolatrie,"

and commanded that they should be thrown into the sea. Some, however, were

rescued, and taken to old churchyards and market-places in the neighbouring

islands, or on the mainland. They are all very similar, being monoliths,

generally of whinstone, and covered with elaborate designs.

The most casual traveller in Argyleshire cannot fail

to be struck by the number of little roofless, fern-fringed, chapels,

distinguished by the prefix of kil or cell, marking the spot as that where

some early preacher of the Cross established himself, perhaps in yet heathen

days. Such are Kil-Choman, Kil-Michael, Kilcoinan, Kilkeran, Kilcoivan,

Kilkevan, Kilcousland, Kilraven, Kifldavic, Kileolan, Kill-blaan, Kil-ewen,

Killean, Kil-Kenzie, where the graves are irregularly scattered in

picturesque confusion among sandhills or grassy knolls. Most of these have

some carved stones —sometimes knights, sometimes ladies, always swords.

On some we find the galley of the Isles; on others

deer-hunts, hounds, otters, creatures like griffins with wonderful tails of

scrollwork, winding about in intricate patterns of foliage or other tracery;

sometimes birds fighting; sometimes shears or other implements of work. AU,

or almost all, are alike nameless, covering the dust of long-forgotten

heroes. Some have niches, in which lie sculptured effigies of bishops, with

their pastoral crooks and mitres, or else knights with broadsword and

battle-axe. Many have one or more of those round-headed, upright crosses,

which we identify with Iona, almost all of a grey whinstone—a hard stone,

not much affected by centuries of wind and storm. Some have inscriptions in

the Saxon character, unintelligible to the unlearned.

Some of the sculptures in the best preservation, are

in the chapel of St. Cormac, at Kiels, in North Knapdale (north of Cantyre),

where there are an unusual number of such memorials. Indeed throughout

Knapdsle, such links to the past are especially abundant, and such spots as

Kil-Michael Lussa, Kiels, and Kilmory, by turns invite attention.

Some very interesting remains are to be seen on the

Eilan More, a little isle at the entrance to Loch Killisport Here there is a

small chapel, and a vaulted chamber, divided into two cells, one of which

was apparently the dwelling-place of the hermit. In the other is a stone

coffin, supported by four grotesque figures. On the lid is the figure of a

priest in his cope, surrounded by elaborate tracery. Outside the chapel lies

a plain stone coffin and a broken cross. Another cross stood on the highest

point of the Isle; on one side was depicted the Crucifixion, with the women

standing by; on the other, elaborate Runic knotting. But now the cross has

fallen, and only broken fragments remain.

At some of these old churchyards there now remains

literally no trace of the ancient cell, only the silent God's Acre, where

sleep so many generations of the simple folk, whose one ambition was to the

where they were born, and where they lived their uneventful lives, hoping at

last, to be laid to rest beside their forefathers, in this quiet spot,

which, from their earliest infancy, has been to them a place of awe and

reverence.

Such lonely burial-grounds always recall to my memory

Wordsworth's lines:

Of Church or Sabbath ties

No vestige now remains.

Yet thither creep

Bereft ones, and in lowly anguish weep

Their

prayers out to the wind and naked skies.

Proud tomb is none; but rudely

sculptured knights

By humble choice of plain old times are seen

Level with earth, among the hillocks green."

The majority, however, still retain some ruins of the

old churches. Others again, do not betray their character by their name, as

Patchen, an enclosure among the sand-hills, where the old tombs are half

overgrown with bent, and half veiled with salt drifting sand.

Many a sad story these churchyards of our seaboard

could tell; of terrible nights in which all the bread-winners of a hamlet

have been lost, and none but lads and women left to fight life's battle.

Such women, though I so brave and hardy; and withal so leal to the dead. In

one of these quiet little churchyards in Yorkshire is a simple headstone,

and the fishers will tell you that the man who lies there, was drowned one

awful night, and the sea did not give up her dead till the end of eleven

weeks !—from December till March; and during all those bitter wintry days

his wife followed every receding tide, scanning each ledge and crevice of

the black rocks,—each pool beneath the slippery, tangled, sea-weed. Vainly

did the neighbours urge her to forego the hopeless search. Early and late

the sad solitary woman was at her post, reckless of the beating storm and

bitter frosty wind, still keeping her weary vigil; and at last, when almost

despairing of success, her prayer was granted, and the waves brought him to

her feet. So she buried him in "mother clay," and watched by the green mound

for upwards of thirty years, ere she was laid by his side.

It really is curious to remark how largely the

numerous early saints of this district have left their impress on the land.

In looking over a list of the parishes in Argyleshire I find the following

goodly proportion, which still retain the name of some once venerated

father, and, of course, each parish may, and generally does, contain several

churches dedicated to others of perhaps equal note.

In other counties the parishes with this prefix are

comparatively few, as here shown.

Parishes in Argyle-shire.

Kil-finichen and Kil-vickeon (Iona), Kil-Brandon and

Kilchattan, Kil-calmonell and Kil-berry, Kil-chornan, Kil-charenan,

Kil-dalton, Kil-mun, Kil-malic, Kil-finan, Kil-arrow, Kil-meny, Killean,

Kil.ehenzie, Kil-maiie, Kil-martin, Kil-morich, Kil-modan, Kil-more,

Kil-ninian, Kil-inver, Kil-meLford, Kil-bride (St. Bridget).

I do not know whether the prefix kin is a corruption

of id!, as Kin-loss (Abbey in Morayshire), Kin-row, Kin-loch-spelvie,

Kinloch-rannoch, Kin-loch-luichart, Kin-cardine, Kin-fauna, Kinclaven,

Kin-naird, Kin-nell, Kin-tore, Kin-nethmont, Kin-gussie, Kin-tail,

Kin-garth, &c., &c.

I also find Kil-churn, Kil-menny, Kil-bervie,

Kil-bucho, Kilcreggan, Kil-finan, Killundine on the Morven coast, and

Kimtuintaik (which last was the cell of St. Winifred); Killouran on Isle

Colonsay, was the cell of St. Oran. Kil-michael Lussa is near to Kids and

Kilmory, in Knapdale. Cantyre has a special cluster of saintly

cells—Kil-Kerran, Kil-Michael, Kil-Chouslaxi (pronounced Kooelan),

Kil-Coivin, Kil-Kevan, Kil Choman, Kil Colmkeil, KilRaven, Kill-Davie,

Kil-Eolan, Kill-Blaan, Kil-Ewen, Kil-lean, Kil-kenaic.

It is probable that some of the saintly names here

quoted may be those of St. Columba's predecessors, for there seems every

reason to believe that the honour of having first introduced Christianity to

this district has been erroneously attributed to him, St. Kieran, whose

church and cave we saw near Campbeltown, having, it is said, come over from

Ireland with a colony of Christian Dairiads, who settled in Argyleshire,

some fifty years before Columba, the fiery Abbot of Durrow, had quarrelled

with, and been banished from Ireland by, the Ardriagh, or President.

It seems that when attending a great meeting of the

lords temporal and spiritual of the Green Isle, Columba was rash enough to

take with him a young son of Aodh, King of Connaught, who was at enmity with

the Ardriagh. Even the sanctity of the Abbot proved no protection for the

young man, who was treacherously slain. Then followed war, in which Columba

sided with the aggrieved father, and eventually received that command to

quit Ireland, which brought his fiery energies to the aid of the little

Christian band of Dairiads in Cantyre; whence he moved onward to that Isle

where, in after years, kings and rulers craved permission to lay their dust

near that of one so holy.

St. Kieran is not the only pioneer of the faith whom

we are apt to rob of honour due, while heaping veneration on St. Columba.

How constantly we hear the latter spoken of, as though he first had brought

to our Western Isles that light of Christianity, which thence radiated to

the farthest corners of the mainland! So far from this being the case, we

know that for a century before the birth of Coluinba, a series of duly

ordained bishops had ruled over Scottish dioceses in various parts of the

land; these being, for the most part, native Christians, who, of their own

accord, had gone to Rome to study. Their existence as Christians gives some

colour to the belief that, so early as the third century, Christ's Name was

known in this land.

The first bishop of whom we hear was that St. Ninian

who, in the end of the fourth century, returned from Rome to his native

county of Galloway, where, we are told, "he ordained presbyters, consecrated

bishops and organized parishes." At Whitehorn may still be seen his Candida

Caea, the first Christian church built of stone in Britain. Here he was

buried, about the year A. D. 430.

In the following year St. Palladius was sent to this

country as "Primus Episcopus to the Scots believing in Christ," and about

the same period St. Patrick appears on the scene. He was born about the year

A.D. 373, in Dumbarton, the place of his birth being named in his honour,

Kilpatrick. Having been captured by pirates and carried over to Ireland, he

was filled with an exceeding longing to Christianize the Hibernians. History

records how he escaped from slavery, and contrived to reach the shores of

Gaul, where he studied the Scriptures for thirty-five years before he was

ordained priest Nor was it till he was about sixty years of age that he was

sent back as Bishop, to commence his mission in the Emerald Isle. The

patient student proved a long-lived teacher, and is said to have died at his

post in his 120th year.

Early in the sixth century, we hear how St. Kentigern

(better known to us as St. Mungo, the patron saint of the beautiful old

cathedral at Glasgow), fixed his see at the place where that city now

stands. To him the credit seems due of first Christianizing part of Wales.

He owed his early training to St. Serf; the Apostle of the Orkneys; so those

remote Isles must have had their first rays of light, long before the

disciples of Iona went thither "as doves from the nest of Columba." The fame

of that most energetic worker certainly has no need to borrow lustre by

defrauding his predecessors of their rightful share; doubtless, when he

landed on this wild shore of Cantyre, his heart was gladdened by the

knowledge that the light he strove to diffuse was already glimmering in

divers corners of the land.

In defiance of the commonly received account of his

having first landed on Isle Oronsay, near Colonsay, and having thence

departed because he could still see Ireland, which he had vowed never to

behold again,—the tradition in Cantyre is, that he first landed at the

southernmost point of the Moyle; and that, although in full view of the

Irish coast, he here built his little church, where he preached for some

time before he went to Iona, leaving his saintly mark on many a nook. At the

southern extremity of the Moyle or "Mull" the men of Cantyre still point out

the "Bay of the Boat," as the spot where his frail currach, of wicker-work

covered with hides, first touched the shore, whence he was to make his way

to the court of Connal MacCongail, King of the Northern Scots, to whom he

was nearly related, being himself of the blood-royal. Connal and his people,

being already Christians, gave him warm welcome, and sent him under safe

escort to Brude, the King of the Picta. He too declared himself a Christian;

and his chiefs and people were not slow to follow his example. Soon even

Broichan, the Arch-Druid, was converted, having been cured by St. Columba of

a dangerous and sudden illness.

To those who accept this form of the tradition,

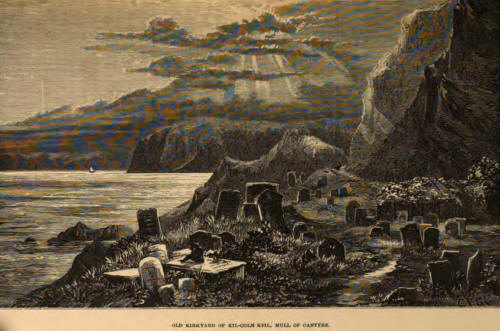

perhaps the most interesting ecclesiastical site of Cantyre is the aforesaid

little chapel, known as Kil-Colm-Keil, the Cell of St. Columba, at Keil,

situated at the extreme end of the Mull of Cantyre,—just such an one as that

where King Arthur was laid, when sorely wounded in that battle among the

mountains beside the winter sea—

"A ruined shrine, beside the place of tombs,

Where

lay the mighty bones of ancient men,

Old knights. And over them the sea

wind sang

Shrill, chill—with flakes of foam."

It is a tiny roofless ruin—its grey walls veiled by

luxuriant ferns which cling to every crevice, and form a soft, green coping.

It lies so close to the sea, that the salt foam dashes over the old tombs,

and the tough green bent creeps up amongst the stones, while bright

sea-pinks gleam through the mossy grass. A steep crag of reddish rock rises

directly above it; and, just beyond, the bluff headland of the Moyle itself

rises abruptly from the sea, which here scarcely ever knows calm, but seems

to revel in its joyous liberty.

There is not a sailor or a fisher on all this coast,

or the opposite shores of Ireland (Antrim being but twelve miles distant),

who does not dread the mighty green waves that are for ever raging in their

ceaseless battle with the stern old Moyle. In quick succession the booming

breakers burst on the unfeeling rocks, which have withstood them for such

countless ages, and now fling them back once more. With swift rush, the

baffled waters fall back on the advancing wave, and thus reinforced, renew

the ceaseless, hopeless attack, —then, "white with rage," dash themselves to

atoms, and fall in dazzling spray and foam over the cliff.

If you count the waves, you will see that about every

sixth is larger than the others, a chieftain in fact; and if, as it curls

proudly over, you can catch a gleam of light through the transparent water,

you will see its wonderful clear green, at the very moment that the land

breeze carries back its crest in tossing spray, like the mane of some white

sea-horse. Most beautiful of all, is the moment when two waves, whose

courses differ slightly, come to a violent collision, and dash their white

spray heavenward,—an encounter which you will here see to perfection, as two

strong currents meet at this point. Perhaps if the sea is not very angry

indeed, there will come a lull— an amnesty,--and the graves that were

drenched with the salt sea spray, will dry in the sunlight; and the

shepherds can put off their boat, and row to the grassy islands to see how

it fares with their sheep.

It was on one of these unwonted days of rest, that I

found my way to Kilcolmkeil. Let each who loves the peace of nature, picture

the scene for himself. The beetling crag,—God's-acre bathed in light,— earth

and sky, gleaming with that clear shining that cometh after rain. And the

hush and silence of the calm wide ocean, noiselessly stealing on and on,

till the great brown rocks, with their wealth of golden seaweeds, lie

hidden, like purple shadows, beneath the cool and quiet blue, and only a

tiny edge of white rippling foam, marks the lip of the lazy wave as it

glides to and fro, or brims over the ribbed sand, glancing and gleaming in

the bright sunlight. Only here and there, the still surface of the waters is

broken by a broad leaf of brown sea-ware, waving idly from the forest below,

with quivering motion, like some curious wriggling sea-snake; or a floating

tangle, like long human hair, washed to and fro, suggests some fancy of the

sea giving up her dead, to this green resting-place. Now and then, there is

the quick flash of some white-winged gull, as it darts upon its prey, and

then again floating UA ward, hangs idly poised in the sunny air.

Altogether it is a scene of most blessed peace, such

as sinks into the heart with strange sweet power, soothing and lulling the

turmoil of its cares. For there is no more dear companionship than that of

the sea, which in its ever-changing moods, seems almost like some human

thing, that one day claims our sympathies with its own wild joys or sorrows,

ready in its turn to weep or laugh with ours; to-day so calm and peaceful,

laughing in the sunlight; tomorrow roused to mad excitement, lashing itself

into wild rage; then, when its wrath is spent, subsiding as though

repentant, lying still and silent beneath the cold mists, dreary and

desolate and sad, —like a sorrowful spirit, when all life's energies are

subdued. They only, who have been cradled and nurtured within sound of that

ceaseless song of the wild waters, can fully realize their subtle charm, or

tell the unutterable yearning for their music,—the craving for their

breadth, for their reflections of the great clouds,—for their incessant

movement, which oftentimes comes over the spirit, when the body is tied to

some monotonous inland region; the unspeakable longing for sight and sound

of the great green waves, the tossing spray and screaming sea-birds, and the

wild breesa that rushes past, laden with the salt sea-brine. None else can

understand the intensity of that passionate love which the sea and its

shores can inspire—the thousand memories linked with those wide white

sands—those slippery rocks—that brown, wet tangle, each leaf of which seems

to have some hidden power whereby to twine itself round the innermost depths

of the soul. None else can sympathize with the bitter disappointment of

awakening from some blissful vision of shell-gathering, or idling by those

great waters, to find that in truth it was but a dream.

To such I say, if you would see Old Ocean in its

glory, come to Cantyre; but those who desire true mountain scenery bad

better stay away, for when once you leave the seaboard and turn inland, you

will find that you have left all beauty behind you; the great swelling green

hills do indeed rise to a height of 2000 feet; but the very name Cnoc Maigh,

or the Hill of the Plain, suggests mere shapeless high ground. Much of this

is amble, but at the tine if our visit, a sore pest was troubling the land,

owing to the lack of frost in the previous winter. This was a gluttonous

grub, which had appeared in countless myriads, and had eaten bare all the

fair green crops, leaving only fields of parched red earth. Some of the

farmers were brave enough to hazard a second sowing, but with small hope of

better success.

But the glory of Cantyre lies in her dairy-farms; the

rich fine soil yielding abundant pasture, and supporting from twenty to

thirty cows on each farm. It is a land flowing with milk and money, with

comfortable, well-to-do inhabitants, who thankfully told us that the cattle

plague had as yet never found its way to their shores. But though the farmer

will offer you wine and spirits in abundance, you must not test his

hospitality so cruelly as to expect such a bowl of creamy milk as any old

"Cailach" in a black bothy would be proud to offer you, should she own but

one gentle "Crummie." At these great dairies, the farmer prides himself on

his unbroken pans of rich milk, therein estimating prospective pounds of

butter and cheese for a sure market.

Looking on these prosperous dairy-farms, the idea very

forcibly suggested itself, that such farms, worked on a co-operative system,

may yet bring gold and comfort to many a district, where, although the soil

is unfit for cultivation, it assuredly affords rich natural pastures, which

could hardly be more usefully employed, both for the farmer and the public.

To the antiquarian, Cantyre offers some special

attractions. I am told that no part of Scotland is richer in relics of

pre-Christian times; cairns and barrrows, monumental pillars erected above

stone coffins, and rude urns containing the ashes of bodies that had been

burnt, having been found in many of its green downs.

There are countless old legends attached to these

green hills, and to the cliffs and caves along the shore; tales of the

warrior and mighty hunter, Fingal, and his faithful hound Bran; wonderful

holes in the rock, that have served for his cooking pots, wherein to boil

rude kettles formed of the skins of the deer, and filled with flesh, such as

he loved to eat half raw, and caves that have been honoured by his presence;

but these tales have been so carefully collected by Campbell of Islay, that

all lovers of such lore need only refer to his 'Tales of the West

Higands'for an inexhaustible store of wild Gaelic legends.

Though by no means one of the most ancient ruins, the

fine old Castle of Saddell, with its ruined monastery and picturesque

kirkyard, are among the most remarkable ecclesiastical remains on Cantyre.

Here quaintly-sculptured tombs of ecclesiastics and warriors lie beneath the

shadow of some fine old trees close to the shore. Two of these represent

knights clad in armour, and round them there are inscriptions in Saxon

character, setting forth that these were Macdoniilds of Saddehl. Several

fine old Crosses have fallen, or been overthrown, and their broken fragments

lie half-hidden by the tangled brambles. Little of the monastery now

remains, as it unhappily proved a useful quarry for ruthless hands, and the

modern dwelling-house has been in a great measure built at the expense of

the church, all the hewn stones having been removed, and the offices paved

with gravestones---a species of sacrilege which, until the present

generation, was terribly common throughout Britain; and indeed it needs all

the efforts of antiquarians to check it even now.

I well remember with what difficulty my father stopped

similar devastation at Kinloss Abbey in Morayshire, where its stones were

rapidly being carried off by neighbouring farmers, to build barns and dykes,

bridges and gate-posts. One fine old stone coffin had been converted into a

pig's trough! There have even been cases where a neighbouring farmer has

spared himself the trouble of stealing the stones, and therewith building

byres, by the simple expedient of making use of the grey ruins of the old

church itself, as a convenient substitute for cattle-sheds, sheep-pens, or

even pig-styes I These neglected churchyards were also treated as monumental

storehouses, whence beautifully-sculptured slabs might be selected to mark

fresh graves, the modern name being roughly' chiselled over the weather-worn

escutcheon of some brave knight of old; or perhaps the robber went so far as

to smoothe the slab, as in the case of that beautiful stone at Hilton of

Cadboll, where the elaborate tracery has been completely obliterated from

one side, and replaced by an inscription to the memory of "Alexander Duff,

Esq. and His Thrie Wives"!

The Monastery of Saddell is one of considerable

interest. It was founded in the twelfth century by one of the Lords of the

Isles—whether by the great Somerled or by his son Ronald seems uncertain,

but it very soon acquired a reputation for sanctity, and great men of old

craved to be buried there. Of Somerled, and his wars with Godred, King of

Man, both old Sagas and Gaelic legends tell many tales. There were terrible

sea-fights, in one of which the Manx fleet of galleys was so sorely beaten,

that Godred was compelled to yield all the Sudereys, or Southern Isles,

including "Yla and Kintyre," retaining only the island of Man itself. The

wife of Somerled was a daughter of Olaf the Swarthy, King of Man and the

Isles.

Various accounts are given of the manner of his death,

but whether in a sea-fight with pirates, or by assassination in his own

tent, seems uncertain. One version is that he sailed with 160 galleys to

besiege Renfrew, and fell in action with the Scottish army. In any case his

body seems to have been brought to Saddell for burial, and laid where so

many turbulent warriors now sleep in stillness, and the only unrest is that

of the restless ocean.

In the castle is shown an old dungeon where Macdonald

starved a luckless Irishman who had the misfortune to own too beautiful a

wife. At first he only confined him in a granary; and the prisoner found

means to get at the grain, and so was kept alive. Then he changed his

prison; but through the barred window a kindly hen came daily, and gave him

her egg. So the flickering flame of life still burned. Once more he was

removed, and cast into this deep noisome cell, where nor bird nor beast

could bring him supplies— and here at length he died, having gnawed his own

flesh in the agony of his hunger. Then Macdonald gave him burial; and the

beautiful wife, looking down from the high tower, espied the funeral, and

asked whose it was; when she knew that it was her own liege lord, she cried

in bitter anguish that she would be with him anon, and with one wild spring,

she dashed herself from the battlements, and was buried by his side.

The ruins of another old prison still remain in the

wood close by, and many tales of the treachery and vengeance of the lords of

Saddell are told in connection with these grey walls.

This part of Cantyre also has one or two traditions of

Robert the Bruce; and the little Isle of Rachrin, off the Irish coast

(distinctly visible from the Mull), was to him a haven of refuge in times of

danger.

In the old Fort of Dunaverty he also found warm

welcome. A few scattered stones, on a rocky promontory, are all that now

mark this old Castle of Dunaverty, "the Fort of Blood," once a mighty

stronghold of the Danes, whose fleet were wont to anchor near the opposite

Isle of Sands, still known to the Highlanders as the wife of Somerled was a

daughter of Olaf the Swarthy, King of Man and the Isles.

Various accounts are given of the manner of his death,

but whether in a sea-fight with pirates, or by assassination in his own

tent, seems uncertain. One version is that he sailed with 160 galleys to

besiege Renfrew, and fell in action with the Scottish army. In any case his

body seems to have been brought to Saddell for burial, and laid where so

many turbulent warriors now sleep in stillness, and the only unrest is that

of the restless ocean.

In the castle is shown an old dungeon where Macdonald

starved a luckless Irishman who had the misfortune to own too beautiful a

wife. At first he only confined him in a granary; and the prisoner found

means to get at the grain, and so was kept alive. Then he changed his

prison; but through the barred window a kindly hen came daily, and gave him

her egg. So the flickering flame of life still burned. Once more he was

removed, and cast into this deep noisome cell, where nor bird nor beast

could bring him supplies and here at length he died, having gnawed his own

flesh in the agony of his hunger. Then Macdonald gave him burial; and the

beautiful wife, looking down from the high tower, espied the funeral, and

asked whose it was; when she knew that it was her own liege lord, she cried

in bitter anguish that she would be with him anon, and with one wild spring,

she dashed herself from the battlements, and was buried by his side.

The ruins of another old prison still remain in the

wood close by, and many tales of the treachery and vengeance of the lords of

Saddell are told in connection with these grey walls.

This part of Cantyre also has one or two traditions of

Robert the Bruce; and the little Isle of Rachrin, off the Irish coast

(distinctly visible from the Mull), was to him a haven of refuge in times of

danger.

In the old Fort of Dunaverty he also found warm

welcome. A few scattered stones, on a rocky promontory, are all that now

mark this old Castle of Dunaverty, "the Fort of Blood," once a mighty

stronghold of the Danes, whose fleet were wont to anchor near the opposite

Isle of Sands, still known to the Highlanders as the gathering-place of the

Danes, by whom it was called Avoyn, 'the Island of Harbours.' Upon it are

the ruins of St. Annian's Chapel, once a place of refuge, where all outlaws

might find sanctuary.

On the ruins of the Danish Fort a new castle was built

by the Macdonalds, who held their own in Cantyre till the days of Montrose,

whose cause they espoused even unto death. But when the star of the

Covenanters was in the ascendant., and the Royalists were driven even to

this Land's End, Sir Aflister Macdonald sailed for Ireland, there to raise

new forces. He left his castle in the hands of his brother, with a garrison

of three hundred men.

Very soon General Leslie, with three thousand of

Argyle's men, advanced to besiege the old fort. Bravely it was defended, but

after awhile, Leslie discovered that the only well for the supply of the

garrison lay outside the walls, and that the water was brought in

artificially. Of course this was at once cut off, and not one drop was to be

had, to quench their raging thirst. It was midsummer, and even the kindly

rains from heaven forgot to fall. Vainly were all eyes strained to watch for

Sir Allister's return, across the sea, whose cool green waves dashed their

salt sea foam so mockingly in the faces of these dying men, at their last

extremity. Sir Allister had been slain in battle; so they might watch till

they were weary, but all in vain.

At length they were forced to capitulate, and for five

days were kept prisoners on their rock together with a hundred more who had

been captured in a cave, or rather, smoked out of it, as the manner was.

Leslie seems to have inclined to mercy towards the captives, but he was

hounded on by a Puritan preacher, Nave by name, and knave by nature, who

insisted on the slaughter "of these Amalekites." At length his counsel

prevailed, and all the helpless captives were either put to the sword, or

dashed from the precipice into the sea, where they lighted on hard, cruel,

jagged rocks. And so they perished (all save one man, and one infant), and

from time to time, bleached bones and skulls are still washed up from the

clefts of the rocks; and the fishers tell how, when the wind drifts the sand

from the bank close by, heaps of human bones are sometimes seen, which the

next kindly wind covers up again with a fresh layer of soft yellow sand.

The escape of the little infant was the only gleam of

light in that day's devilish work. Its nurse caught it up naked in her arms

and fled along the shore. She was stopped by a Campbell, and vowed the child

was hers: "It has the eye of the Macdonald" was the answer. Nevertheless,

the heart of Craignish was soft, and, dividing his plaid, he gave her half

for the naked baby, and suffered her to escape. During those five days of

waiting on the rock, another Macdonald drew near, with a small body of men,

to relieve the garrison. As soon as the piper perceived them, he struck up a

note of warning to bid them turn back. Thus they were saved from the cruel

fate that awaited their brethren; but the piper paid dearly for his tune,

the enraged Campbells cutting off his fingers to prevent his playing any

more such strains.

Thus it was, that Cantyre passed from the hands of the

Macdonalds to those of the gleed (squinting) Marquis of Argyle and his

clansmen. It seemed as though Heaven's righteous retribution sought them

out, when, ere many years had past, a terrible plague came and utterly

depopulated the whole of Cantyre. It was the same year that the Great Plague

was raging in London. The pestilence swept over the land in visible form, as

a great white cloud laden with death—just such a cloud as, in later days,

has rested on Malaga, and other cities, in times of cholera (on Dumfries,

for instance, where in 1843 the cholera raged for months, nor ever stayed

its ravages till one-third of the inhabitants were laid in great pits in the

overcrowded churchyards. And during all the time that the Angel of Death

thus brooded over the city, a pestilential cloud hung like a death-pall,

floating in mid-air, above the circle of hills which enclose the city as in

a cup. It was a dull heavy film, through which neither the foul air could

escape nor could fresh air circulate, but all was dead stagnation; even the

sunbeams passing through were discoloured, and fell with lurid glare upon

the scene of horror below). The fever-cloud rested long on Cantyre, and left

its traces for many generations. So sorely did Argyle's estates suffer, that

moneys were voted by Parliament for his relief, while the poorer folk

received such help as the churches could collect.

A sunnier legend of Dunaverty in its palmy days, tells

how its chief rescued the fair daughter of the King of Carrickfergus from

the pillion of O'Connor, the King of Innisheon, who had run away with her

against her will. He restored her to her father, and continued his honoured

guest till, in his turn, he claimed the maiden's hand, and was cast-into a

dungeon to rue his presumption. Thence rescued by the damsel, he escaped to

Dunaverty; but once more returning in quest of his love, found that she too

was now in durance vile, for having aided his flight. So, like the hardy

Norseman of old, he showed that neither bolt nor bar could part him from his

own true love, and carried her safely across the sea to his own old castle.

The wrathful king followed in his galley, with many mighty men of war,

vowing swift vengeance. Happily counsels of peace prevailed, and the lady

obtained pardon for her lord; so they all went back together to the Emerald

Isle, and lived merrily to the end of the chapter, and their children became

kings, from whom the Earls of Antrim claim descent.

About two miles from Campbelton lies the old kirkyard

of Kilcousland, one of the many which, to me, give an especial charm, to

these green shores; lying, as they do, almost within reach of the wild

spray, which, dashing heavenward, falls in lightest showers over the rank

grass and golden iris, and mossy stones, beneath which sleep so many

forgotten generations. Kilcousland has no gravestones of especial interest,

but (half hidden by large-leaved coltsfoot and dockans, and stately tall

white hemlocks) are many which are quaint and old, and though the majority

only show crowns and shields and grotesque death's-heads-and-crossbones, and

fat-faced cherubs with lumps of moss for their eyes, or else such growth of

golden lichen as Old Mortality would have loved to scrape away, there are

some devices which tell the daily work of the sleeper forcibly enough. Thus,

a ploughman has quite a graceful grouping of reins and harness; a carpenter

keeps his hammer and saw and sundry other tools; while the tailor carries

his shears and his goose to the end of time.

On the broken shaft of an old cross, a carved galley

tells of some forgotten Island chief, while a neighbouring stone bears a

knight's two-handed sword, surrounded with runic knotting. The next tomb

bears only a heavy dagger on a shield, no name to mark who sleeps beneath.

I sat for many hours in this calm "God's acre," in the

shade of the ruined church, watching the ever-changing colours of the quiet

sea, upping up to the foot of the green hill on which I rested; constant

changes from blue to green, and purple and silvery greys, all blended by the

reflection of every tint of sky and cloud, according as the angle of the

broken wavelet either mirrors these, or lets u4 see beneath its surface,

into its own depths; giving us hints of the wonderful world below the

waters. There were broken reflections, too, from the hills of Arran, and

from Ailsa Craig, which is a very tine rock-islet, at the entrance to

Campbelton harbour. In form it resembles the familiar Bass Rock, rising

precipitously from the sea to a height of 1100 feet. It is a mass of grey

columnar basalt, which to the north-west presents a very grand face of great

basaltic columns. On the opposite side are the ruins of an ancient square

tower, on a high rock-terrace overlooking the sea. It is a very green isle,

and affords pasture to many goats. A multitude of rabbits and innumerable

sea-birds also hold the Craig in possession.

Now and then I watched a white sail round the

lighthouse, and enter the quiet haven. I thought of the words of one whose

dying prayer was—

"Lay me beneath the grass,

Where it slopes to the

south and the sea;

Where the living I love may pass,

And, passing, may

think of me"—

and I thought that just such a churchyard as this was

the resting. place for which she craved. It was a scene of great peace, and

I lingered till the blue sky of noon had changed to that pale primrose

against which each form of earth cute with such intensity of colour; and the

evening breeze, rustling among the tall flags, sounded like a mysterious

whisper from the sleepers around me. The saint to whom this spot was

dedicated, was a certain kindly old St. Couslan, whose sympathies were all

on the side of young couples whose true love was thwarted by stern parents

and guardians. To make matters easy for them, he set up near his cell •

large stone with a hole in the eentre, and announced that runaway couples

who succeeded in reaching this stone, and here joining hands, should be

considered indissolubly united. Here we have a trace of the earlier paganism

—a survival of that old Norse custom of betrothal, which bade lovers join

hands through a circular bolo in a sacrificial stone. This was called the

promise of Odin, and was practised in the Northern Isles long after they had

embraced Christianity.

The custom was long observed in Orkney, where, a

little to the east of one of the two clusters of large standing stones (the

stones of Stennis) there was one stone with a hole right through it. To this

stone of betrothal came all the Orkney lovers, to plight their troth by

clasping hands through the perforated stone. This ceremony was considered so

binding, that there was no downright necessity for a subsequent marriage

with Christian rites. Indeed there were certain advantages in dispensing

with such a ceremony, as those who were joined together with the sanction of

the Church could never more be parted, whereas those who had dispensed with

it, and had only bound themselves by the promise of Odin, might, should they

grow weary one of another, legally annul their marriage, by merely entering

the Church of Stennis, and there parting.

"They both came to the kirk of Steinhouse," says Dr.

Henry of Orkney, "and after entering the kirk the one went out at the south,

and the other at the north door, by which act they were holden to be legally

divorced, and free to make another choice."

The celebrated perforated stone of Stennis is known to

have been an object of veneration to the men of Orkney, long before the

Northmen came, and called it after Odin, and the people continued to hold it

in reverence till the beginning of this century, when it was destroyed.

A simple and more poetic form of betrothal was for the

lad and lass to stand on either side of a narrow brook, and to clasp hands

across the stream, calling on the moon to witness their pledge.

Sometimes the young couple each took a handful of

meal, and kneeling down, with a bowl between them, emptied their hands

therein, and mixed the meal; at the same time taking an oath on the Bible

never to sever, till death should them part. A case was tried in Dalkeith in

1872, where this simple marriage ceremony was proved by Scotch law to be

legally binding.

But the commonest and certainly the most curious

custom of betrothal, was that of thumb-licking, when lovers licked their

thumbs and pressed them together, vowing constancy. This was held binding as

an oath, and to break a vow so made, was equivalent to perjury. This custom

is still quite common in Ross-shire, on concluding all manner of bargains,

such as sales of cattle or grain. Hence the saying, "I'll gie ye my thumb on

it," or, "I'll lay my thoomb on that," expressing that the statement last

made is satisfactory. There are men still in the prime of life, who remember

when the custom of thumb-licking was the recognized conclusion of business

transactions, even so far south as the Clyde, and not unknown in Glasgow

itself.

Whatever may have been the origin of this quaint

ceremony, it is curious to remember that the ancient Indian custom on

sealing a bargain or conferring a gift was to pour water into the hand of

the recipient, as is shown on many sculptures. Probably the thumb- licking

was a convenient substitute for the original symbol.

Another saintly Father, who was reputed to take

considerable interest in the matrimonial affairs of his people, was St.

Coivin, who gets the credit of having established a most extraordinary law

of divorce, which assuredly savours of earlier pagan days. He is said to

have invited all unhappy couples to meet at his cell on a given night, when,

having blindfolded each person, he started them on a pell-mell race thrice

sunwise round the church. Suddenly the saint would cry "Cabhag!" i. e. seize

quickly! and each swain must catch what lass he could, and be true to her

for one whole year, at the end of which, if still dissatisfied, he might

return to the saintly cell, and try a new assortment in the next matrimonial

game at blind-man's-bull!

The spot where these strange games at blindfold love

were played, is the old kirkyard of Kilkevan, on the high ground overlooking

Macnahanish Bay, one of the most attractive, though loneliest, reaches of

our sea-coast. Here the finest golden sands stretch for miles along the

shore, where the great green waves break ceaselessly. To me St. Colvin's

cell was a specially attractive sketching-ground, with its distant view of

the five blue peaks of Jura, its pleasant surroundings of grassy downs,

fragrant with lilac orchids and the quiet ivy-covered ruins. Many of its

sculptured gravestones are of unusual beauty. Some of these bear the figures

of knights, with sword as long as that of Robert the Bruce, and devices of

the chase or

armorial bearings carved all round them. Others have

no figure, only one long sword; some have only daggers. There is no mark to

tell who sleeps beneath, or whence came the stones, though the people have a

tradition that they were brought from Iona,—which, indeed, is likely enough;

not as the spoils of ruthless pillage, but as the handiwork of some of the

holy brethren, well skilled in cunning stone-work, who doubtless supplied

these monuments to such of their neighbours as were willing to pay for them.

Be that as it may, the carvers and the knights have been alike forgotten for

many long ages, and here they still lie, all facing the east— waiting. The

restless agitation of the mighty waters has not troubled their sleep;

though, to the idle dreamer who lies among the golden iris watching the

broad lights and shadows passing quickly over old Ocean's face, it seems

such a constant emblem of the tossing and unrest of life, that he cannot

well put away the thousand thoughts thus awakened, and as the murmurous

echoes rise and fall with the breeze, they seem to whisper the words of an

old song :-

"Like the wild ceaseless motion,

Of the deep

heaving wave,

Is our heart's restless beating,

From our birth to our

grave.

Toss'd by strong stormy passions

On the swift wind we flee,

Till life's bark reach the haven

Where is no more sea."

No spot on earth could well be more peaceful than the

shores of beautiful Macnahanish Bay, and the green woods and braes of Losset,

where we have spent so many pleasant days. The fields close to the house are

white with narcissus, the uncultured growth of many generations; while

genuine wild flowers—blue and green and gold—riot in the shelter of the

glen, and all day long the mavis and merle pour forth their jubilant songs

in the quiet wood.

It is curious to note how the absence of frost favours

the growth of plants too delicate for our eastern coast. Camellias bloom in

the open air, and great hedges of crimson fuschia live securely all the

winter, on the lee side of sturdy fir trees, whose upper branches, however,

are all scorched by the blighting sea-winds.

I wonder what peculiarity of atmosphere causes the

wonderful splendour of the sunsets on this coast. You know how much we have

always heard of the amazing glory of sunrise and sunset in the East, more

especially during the rains. I may safely say that during a residence of

several years in various parts of the tropics, I have scarcely once

neglected to do homage to these outgoings of morning and evening, but, with

perhaps two exceptions, I have seen nothing that could bear away the palm of

beauty from our own skies; and I am more and more tempted to believe that

these it comparisons" are due only to the different hours of rising and

dining, which compel travellers to use their eyes in a way they quite forget

to do when at home.

Have you not sometimes wondered at the dull hearts,

and blind eyes, that could scarcely glance westward for one moment, though

the golden gates seemed to have opened behind the heavy purple clouds, just

flushed with rosy crimson; and all so quickly changing; softening and

mellowing in the hazy sunset light, till earth, and sea, and sky alike lay

steeped in loveliness I Blind eyes they must be, that have not yet been

opened to read the Divine Book of Nature, written day by day by the finger

of GOD Himself; the GOD of Infinite variety, Whose worship men are so apt to

reduce to a mere system of forms, of infinite sameness. Surely the mind that

most dearly loves to drink in the beauty of the visible world, must be the

most in sympathy with that of the Great Artist Who delights in creating such

refinements of beauty, "rejoicing in His work."

One advantage over the sunsets of the East we

certainly possess, in the long, beautiful, hours of twilight, when the

curlew and the plover alone are on the wing; and that still later hour

"'twixt the gloaming and the mirk" when all voices of nature are hushed,

except the grand music of the sea, murmuring its endless harmonies to the

wild bent hills.

I doubt if there is any spot in all the British Isles,

where you may study Old Ocean in all its varied tempers more perfectly than

you can here, in beautiful Macnahanish Bay, which lies outspread before our

windows, so that morning, noon, and night we watch its changing moods. From

earliest times this spot has been noted for the tremendous size and roaring

of the waves, which on the slightest provocation seem to lash themselves to

raging fury, and many a brave ship has perished here, deceived by the

lowness of the land, and so lured on to destruction.

The whole force of the broad Atlantic seems to sweep

into the Bay, as the great wild waves rush onward, chafing in their

tumultuous wrath, albeit with such "method in their madness;" rising and

swelling so deliberately, as each mighty green billow curls and breaks, in a

crest of gleaming foam; and the seething water dashes noisily over the

shingle, bubbling and surging among the masses of rock which lie heaped in

such grand confusion along the coast—or else tossing its spray in wild

sport, right over the cliffs and caves, where the delicate ferns are

nestling, to the green bank above, where the young lambs are learning to

crop the sweet short grass from those dangerous ledges, and spring back,

startled, by such chilling practical jokes.

The waves are not idle in their sport. They are

washing up great masses of brown sea-ware, not carefully gathered with a

loving hand, but torn up by the roots, from the great gardens in the ocean

depths. And the poor kelp-burners are watching anxiously to see what harvest

they may hope to reap. Some have only their creels, rough wicker baskets,

which they carry on their own shoulders, but here and there is a little

cart, drawn by a strong pony; a willing little beast, which strains every

nerve to drag its burden of wet, heavy weed, over the rough shingle, to some

spot above high-water mark, where it may be spread over the grass or sand,

and left for several days to dry; this is the most anxious time in the

harvest, as anxious as haymaking, in this uncertain climate; for one heavy

shower of rain will wash away all the precious salts and iodine, and leave

the beach strewn only with useless lumber.

As soon as it is safely dried, the weed is heaped into

little stacks, till the last moment, when the furnace is ready to burn it.

It is not "all fish that comes to the net" of the kelp-burner. Those broad

fronds of brown wrack' which strew the shore are useless to him. He most

values the masses of brown tangle covered with little bladders, and when the

tide goes out, he will cut all that he can find growing on the rocks, and

add it to his store; this being by far richer in salts than that which is

cast up by the sea.

Let us sit down awhile, and watch him burn those

brown heaps which he collected last week. We cannot stand on the open shore,

or the bent hills, for the wind is blowing inland with such violence, that

we should be sent right across the Isthmus—but there is a green bank at the

foot of the cliff, facing the sea, where hardly a breath of air stirs the

blue-bells and foxgloves; for the wind strikes the shore in front of it, and

then seems to be thrown upward at a sharp angle to the top of the crag, and

though we seem to be right in the wind's eye, we shall really be in perfect

shelter. This is a wrinkle, which holds good for all rocky coasts.

Now the kelp-burners have made their kiln—it is

a long deep grave lined with large stones. First they sprinkle a light

covering of dry weed over these stones, and coax it till it burns, then

slowly they add a handful at a time, till the grace is filled, and heaped

up, with a semi-fluid mass, which they stir incessantly with a long iron

bar; and a very picturesque group they are, half veiled by volumes of white

opal smoke which has a pungent marine smell.

This work will go on for hours, and when all the

tangle has been burnt, the kiln will be allowed to half-cool, and its

contents cut into solid blocks of a dark bluish-grey material. These very

soon become as hard and heavy as iron, and are then ready for the market.

From this material much carbonate of soda and various salts are obtained.

But its most valued product is iodine, precious alike to the physician and

the photographer. Till very recently this was only to be obtained from the

ash of dried sea-weed, consequently the discovery of its various good

qualities gave a renewed impetus to the kelp trade. Now, however, iodine is

more cheaply and readily obtained from crude Chili saltpetre, so the demand

for kelp has again decreased. Moreover, it has been discovered that much of

the iodine which was altogether wasted in the process of burning, can be

saved and utilized by a process of distillation.

Kelp was formerly of very great value in the

manufacture of soap, alum, and glass, but it is now found that crude

carbonate of soda of better quality, and cheaper, can be obtained from

sea-salt. Moreover, the great extent to which potass is now imported has

proved a very heavy loss to the kelp-burners, whose hard work consequently

brings a comparatively small return. And years ago, the removal of the duty

on Spanish barilla was a matter of ruin to many of the Islanders, chiefly

those of Skye, where the weed contained a much smaller proportion of the

precious salts, than on other shores, such as those of Orkney, and where,

consequently, this manufacture has been entirely given up.

Kelp-making does not appear to have been one of

the industries of the Isles till about the middle of last century, when it

became a distinctive feature, and so lucrative that some small farms paid

their whole rent from the produce of the rocks. Thus it came to pass that

the shores and rocks were sometimes let separately from the farms; and then

the farmers were badly off indeed,—as indeed they are still, having to go

miles to collect the necessary sea-weed wherewith to manure their fields,

sometimes carrying it in creels on their backs for several miles, or

fetching it in boats from long distances across the stormy seas. When the

value of kelp was at its height, several farms in the Orkneys actually rose

in rental from 401. to 3001. per annum.

The Orkney kelp is used in the manufacture of

plate-glass, and fetches double the price of that made in the Hebrides,

which is only fit for soap. Nevertheless in the year 1818 no less than 6000

tons were produced in the Hebrides alone, and sold at £20 per ton. In that

year the kelp harvest of the entire coast of Scotland was upwards of 20,000

tons, and was valued at half a million sterling. Within the last few years,

the price of kelp in the Hebrides fell to about 41. per ton. In former times

61. was the average, though it varied from 21. to 201. This high price was

of short duration, and only continued during a sudden failure in the supply

of Spanish barilla. When you consider with what infinite labour and risk

this crop is gathered, and that every ton of kelp represents twenty-four

tons of sea-weed, you must allow that there is pretty stiff work for the

money, and that these kelp- burners do not eat the bread of idleness. The

price obtained for kelp has continued gradually to decline, and latterly its

manufacture has, in many places, been altogether abandoned, though the loss

of this source of revenue is a serious matter to the people. It seems

probable, however, that science may come to their rescue by utilizing the

sea-weeds—once accounted so worthless, but now known to be so exceedingly

precious. In the first place their value is now so fully recognized, as

forming the submarine covert, wherein the baby fishes find not only food but

a refuge from their foes,—that on some parts of the British coast

(Devonshire) the Board of Trade has prohibited the cutting of sea-ware.

But to all our shores, old Ocean brings a

liberal supply of drift- weed, precious to the farmer, to whose land they

supply the phosphates and salts which nourish all plants. Cattle too, and

horses, and sometimes sheep, find their winter fodder on the shore, and in

times of scarcity many of our poor fellow-subjects eke out their scanty

living by the use of certain sea-weeds, chiefly those known as dulse and

tangle, which are offered for sale in many of our Scottish towns, not in the

prepared forms, which to the Chinese and Japanese appear so appetizing, but

in their crude, uninviting state. Now, when all food-products are being

scientifically discussed, the merits of this great family are being

realized—a family, moreover, of which not one poisonous species is known.'

So now wise men are turning their attention to methods for utilizing these

edible properties as food for man and beast; and in addition to these, many

other good qualities are now being discovered. It is found that sea-weed

yields a jelly ten times as strong as isinglass, and, by a new process, this

glutinous matter can be separated from the weed, and an altogether new

substance is obtained, to which the discoverer (Mr. Stanford) has given the

name of Algin. It closely resembles horn, and has all the properties of

strong glue, and of a transparent starch; and has already been applied to

many practical uses,—in stiffening fabrics, in applying carbon to the lining

of boilers, &c. &c. The weed from which it has been extracted is known as

cellulose. It is bleached, to a fairly pure white, and being dried and

pressed, forms a rough material, which seems likely to prove an excellent

substitute for rags in the hands of the paper manufacturers. The other

processes, to which weed is now subjected to obtain its salts, leave a large

residuum of charcoal, which has a value of its own as an effectual and

economical deodoriser. Altogether the prospect3 of sea-weed are looking up,

and there seems good reason to hope that the Hebridean Isles may yet find a

source of wealth in reaping the sell-sown crops, of these their great

natural harvest-fields.

Of all beautiful sandy shores, I know none to

compare with the golden beach of Macnahanish Bay, where the broad firm

strand stretches for miles along the coast, making the pleasantest drive

that can well be imagined, close to the water's-edge, where the sand is hard

and firm, and the rippling wavelets run up past the horses' feet, and

retreat again, till you become giddy with watching them, and are fain to

look away across the mellow sea, to where the sun is sinking behind the

hills of Islay, and the five blue peaks of Jura. This drive along the sands

being the shortest road to Tarbert, it is not only on fine days that it

proves tempting, and sometimes the well-trained horses, who have never felt

a whip, but work gladly in obedience to their master's kind voice, have a

difficult task to make their way, with blinding surf almost bewildering

them.

Once, only once, the beautiful shore proved

treacherous. A long line of shingle had been thrown up, by an unusually

violent tempest, and great beds of wrack lay between that and the sea, till

day by day, fresh layers of sand were blown up, and washed up, and it all

looked smooth and firm as usual. But underneath, the hidden weed lay

rotting, and as we drove confidently along, suddenly we found ourselves

sinking lower and lower into dangerous quicksands. The good steeds knew the

danger, and with violent effort dragged us out into the deeper water; and

so, got round the perilous bank, which stretched far along the shore.

Happily the sea was a dead calm, or we should have had a poor chance of

escape, especially as we had tied the children into the carriage with a

series of intricate knots, to prevent their jumping out to catch jelly-fish

and such-like treasures.

|