|

The paralysing calamity of the Great World War put an

end for the time being to normal trade. Manufactures had to give place to

munitions, and naturally the confectionery trade

was one of the first to suffer. After thirty years' struggle, business

seemed to have been firmly and finally established at home and abroad; but

the war shook it to the foundations. From the very nature of the business

he could expect little consideration in such an emergency as that with

which the nation was confronted, when its very life was threatened. The

effect was felt immediately after war was declared, for the first

commodity to become scarce and to be controlled was sugar, the chief

article used in the manufacture of his goods. The war years were in many

ways more difficult and trying than any that had preceded them. Mr.

Mackintosh's health also was now greatly

impaired, and he was the less able to bear the

anxieties of that terrible period. But he did his best to carry on and to

hold the business together, while his sons and his workmen went into the

firing line. The staff was rapidly depleted—men left for the Army or the

Navy in quick succession, and generous assistance was rendered to their

families by the firm. As sugar became more scarce the ration to

manufacturers was reduced ; until only twenty per cent. of prewar supplies

was allowed. The business at home was kept together with difficulty by

rationing the shops in proportion to their former sales; but

the export business, which he had built up with so much care and expense,

was for the time entirely lost.

Writing at this period to the

author, he says :-

"I have just an interval between one interview and

another. I am at my office, a nice cosy place in winter, as I am over the

boilers, and although the office floor is concrete the heat comes up. Yes,

it is nice now, but in the summer it sends me home.

"It becomes more and more

difficult to steer our 'Toffee de Luxe' ship through the troubled seas. We

had over one thousand workpeople before the War, and now we have not quite

two hundred and fifty. Of course we have only twenty per cent. of the

sugar, and our output is down in like proportion; but still we will not

grumble if we are just allowed to keep the wheels going round, so as to

hold the organisation together until after the War. Inconveniences we

expect, considerable sacrifices we would gladly make, but to shut up a

concern like this altogether means disaster. One never knows in these days

what is coming, but I always hope for the best."

Nearly two-thirds of the men left

for active service or for other forms of war work, and hundreds of the

girls, who had been accustomed only to the light and cleanly work of

wrapping and handling toffee, went to Munition Works and learned to handle

deadly explosives or heavy shells. Both Mr. Mackintosh's sons, who were

with him in the business, left for the King's Service, the younger for the

army and the elder for the navy; and he himself, in his fiftieth year, was

called up for medical examination and classed C3!

There was no more patriotic firm than Mackintosh's in

the country, and whether the demand of the moment was for men, materials

or money, it was always met to the fullest extent, and Mr. Mackintosh was

justifiably proud of the record of his firm and his employees. Not only

were the wives and families of those who joined the colours treated

generously so as to make up in part for the loss of their bread-winners,

but especial care was bestowed on the relatives of men who laid down their

lives in this great cause. Over thirty of the young men employed by the

firm made the supreme sacrifice, which was also the supreme achievement.

For much is done for a cause when men are willing to die for $t. Mr.

Mackintosh wrote personally, at regular intervals, to the men at the

front, and sent out parcels to them; and none of

them returned on leave without calling to see the "Boss," who would then

put everything aside, no matter how busy he might be, in order to speak

a few cheering words to them and express the

hope that they might have a speedy and safe return.

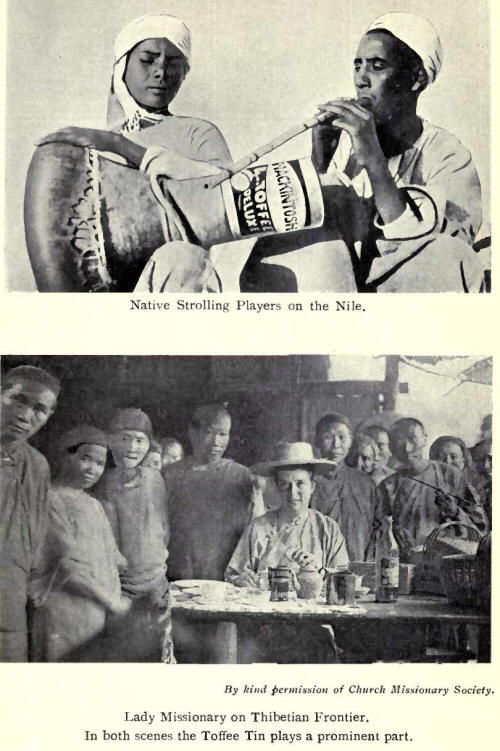

Great quantities of Mackintosh's Toffee were

despatched to the troops and to the Navy in all parts of the world. Anyone

who was at the front, on land or sea, knows that nothing was more welcome

to "Tommy" or to "Jack" than the familiar tin. It lasted longer than

chocolate and that was an advantage, as it helped

along the leaden, weary hours. Before the war the chief ration allowed in

the German Army for forced marches was sugar, and our own military

authorities soon realised the food value of toffee, and of the war output

of the factories a large proportion was taken by Government Departments

for the troops.

All men on active service were

familiar with the large oval tin from Halifax, for its size and shape made

it invaluable for use in a thousand different ways. Millions of these tins

were sent across to France and to other and more distant theatres of war,

because they made such splendid packages for parcels, and the shops at

home were scoured for the empty tins; but long after the boys had disposed

of the good things sent from home the tin itself was put to. ingenious

uses.

An officer of the

Flying Corps wrote, that he was flying behind the German lines when a

defect in his machine caused him to make a forced landing. The trouble was

found to be in a fractured exhaust-pipe. An emergency repair had to be

made on the spot, but what could he use for the purpose? Suddenly he

thought of the oval tin which he had with him. Whipping out his cutter and

soldering iron, be speedily patched the damaged tube, and was able to gain

the air again before he was observed by the enemy. He returned safely to

his own lines by the help of a Mackintosh Toffee tin. A photograph

of the repaired pipe, showing clearly the familiar design on the tin,

accompanied this letter.

A former employee wrote from the trenches, "somewhere

in France" :-

"I cannot get

away from the old firm. We are in the front line trenches now, and between

us and the 'Boche,' right in the middle of 'No- man's-land,' is an empty

four-pound 'Toffee de Luxe' tin. Whenever either ourselves or the enemy

have nothing particular to do, we spend the time potting at the old tin.

It is fast disappearing, but through my periscope I can just make out the

old familiar bowl of cream, and it reminds me of home

and the good old firm."

An officer, a returned prisoner of

war from Austria, brought home with him an improvised kettle which he and

his companions had made during their period of enforced idleness. It had

been very ingeniously fashioned from two of the oval tins.

A member of the firm, who happened

to be visiting Germany on business at the time war was declared, was

interned for the whole of the period from 1914 to 1918, in a civilian

camp. As he spoke German fluently, he soon gained considerable influence

in the camp. After he had been about a year in exile, a letter was

received by his friends at home saying that one of the interned prisoners

was being exchanged, as he was an elderly man and unfit for military

service. The writer also stated that the released prisoner would visit

Halifax and bring with him a letter "two feet" long. The man came as

stated, but, much to the disappointment of the friends in Halifax, he

brought no letter with him, but only a parcel containing a pair of bedroom

slippers, which he said he had brought as a present from the prisoner

still in Germany. For many days they puzzled over the promised letter and

the gift of slippers. Eventually light dawned on this cryptic message.

Were the two slippers the "two feet" mentioned, and was the letter

concealed somewhere in them? Tearing the soles apart they found hidden

between the inner and the outer portions a letter from their friend in one

slipper, and in the other several papers closely written in German. These

they brought to Mr. Mackintosh and sought his advice. The letter stated

briefly that one of the men interned at the camp was a German naturalised

as an Englishman, who had lived in England for many years prior to the

War, and he was now offering his services to the German Government as a

spy in England. The German had been released to go on "special service to

England," and the friend from Halifax immediately searched the quarters

recently occupied by the spy. He found copies of the letters that had been

written to the German authorities, and carefu1y hid them about his person.

Shortly afterward the prison officers came down and made a thorough search

for the missing documents. The entire camp was turned inside out, but

without result. It would not have been safe to tell all this to the

messenger who brought the slippers it was better that he should remain in

ignorance. Hence the message and the mysterious allusion to the "two

feet."

It was clever and ingenious, and Mr. Mackintosh felt

proud of the man, who, under such difficult circumstances and at such

personal risk, sought to serve his country. The German papers were

translated, and as they were evidently of some importance, the whole of

the documents were forwarded to the Foreign Office. Nothing further was

heard of the matter until after the War, when the authorities acknowledged

that these papers supplied them with evidence that enabled them to

identify and arrest several dangerous spies in this country. Mr.

Mackintosh then approached the Foreign Office urging the propriety of some

practical recognition of the valuable services rendered. By his efforts a

substantial reward was obtained for the young man, which came as a

pleasant surprise to him when the German Internment Camp was disbanded and

he. was able to return home.

|