|

"It

is so easy to form wrong ideas of people of different nations through

superficial knowledge. The more one has travelled the broader one's mind

becomes."—J.M.

Mr. Mackintosh

considered that the attitude of the missionary to foreign lands afforded a

parallel for the business man's attitude to foreign trade. "One cannot

wait," said he, "until the home Church has brought everyone into its fold

before sending out missionaries into other lands, or the missionary cause

would never have begun; and so also in business, you must reach out abroad

while extending at home, if you are to be first in the foreign field as

well as in your native Land."

Naturally, his thoughts turned to the mighty United

States Republic, with its eighty millions, or more, of potential

customers. When the American is not smoking he is chewing gum or candy,

and his wife and children willingly assist him in the consumption of

sweetmeats. What an opportunity was thus presented to a toffee

manufacturer blessed with faith and vision!

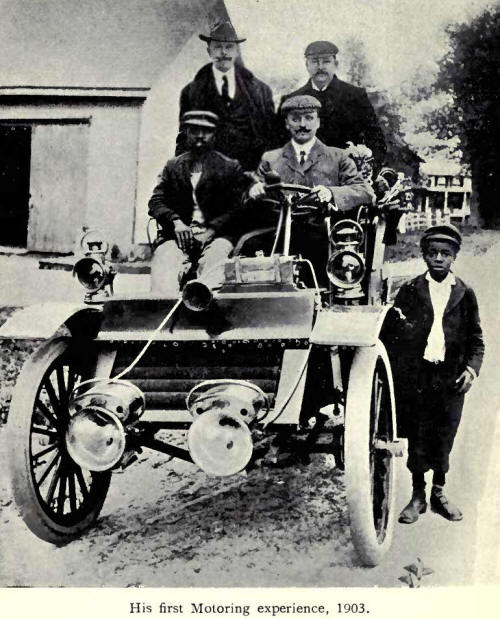

In the autumn of 1903, in company with his

brother-in-law, he undertook a lightning tour through America and Canada,

exploring these countries for the purpose of ascertaining their business

possibilities. Men of adventurous spirit have gone to America prospecting

for gold or other precious metals, but surely this was the first occasion

on which a man ventured to the other side of the world

prospecting for business in such a simple homely thing as toffee. All the

principal cities were visited from New York to San Francisco, from

Montreal to Vancouver. For a month nearly every night was spent in the

train, but during the day the travellers would alight and make careful

observations. Gradually the conviction was formed in Mr. Mackintosh's mind

that he could establish his business in America, and he determined to make

a bold bid for trade in the West. The heavy duty on confectionery imported

into the United States made it impossible to compete with Americans by

goods manufactured in England. It was necessary to erect factories and

produce the toffee on the spot. These difficulties did not appeal him, as

they certainly would have appalled a less determined man.

His Notes of travel in America are

so full and so suggestive that we cannot do better than to print them as

they are written, adding little by way of comment. He went to America when

he was thirty-four years old, and though the primary purpose of the visit

was for business, his Notes are far more than a bare record of business

transactions. They are full of items of general interest; they are written

in a clear, trenchant style, and they reveal in every line the kindly

personality of the writer. Here we have vivid pictures of all happenings

from the time he steps on board the great ocean liner until his eyes are

again gladdened by the sight of his beloved Halifax.

He was a poor sailor, and from

childhood dreaded the sea.

"In my boyhood's days," he writes,

"I had an aunt who went to live in America. Her letters told of the

voyage, its storms, inconveniences and terrors; and subsequently, when she

was on a visit to England, her relation of these experiences, with added

effect, made me determine that America should be one of the last places I

would visit. I never did like being on the sea. Whenever I heard people

speak of it as the 'beautiful, bounding ocean,' in my own mind I added a

few adjectives of a different nature. My aversion for the sea has grown up

with me, and whenever I have to take a journey that entails a sea trip I

look out for the shortest possible passage. I have, however, long since

learned that if a man is to be a man he must face sometimes that which he

does not like, in spite of pre-conceived ideas, and he has to be

determined to overcome the difficulties that would retard his progress.

Therefore, when I felt it necessary for me to make a business journey to

America, I put aside my repugnance for the sea, to do as a duty what I am

sure I never should have done for pleasure. Like most people who act in

this wise, I got a great deal more pleasure out of the sea than ever I

anticipated. Difficulties that look like mountains, or oceans, are often

not nearly o formidable when challenged. Fortunately for me, I lived a

generation later than my aunt, who crossed the Atlantic long years ago."

His first voyage was on board the

White Star Liner "Cedric." Here is a vivid picture :-

"Now the very last trunk is on

board, the gangways are lowered. Look at that little midge of a tug-boat;

surely it is not going to try to pull this giant round? A great crowd of

people assemble to watch the giant off. It was at this moment that we on

board appreciated the red coat worn by one member of the party seeing us

off, for as the little bantam of a tug-boat pulled and pulled, we

gradually ran out into the river, and the people on the shore dwindled

from grown-ups to children, then into dwarfs, then into shrimps, then into

flies, then midges, then specs, then mist! Out came our glasses and lo!

there was the red coat again with handkerchief waving. A minute longer and

even the glasses failed to locate the coat, and we turned our faces

towards our state-rooms to make preparations for the long voyage."

"As we lay in Queenstown harbour a

small steamer raced out to us bringing more luggage, more emigrants, and

hiore mails, and last but not least, the Irish-lace women. These women

came on board the moment the gangway was lowered. In fact one buxom girl

did not even wait for that, but was hoisted up by the luggage rope. We had

a lively half-hour. Their tongues never stop for a moment; yet they are

keen on business, and they know that their time is short. Evidently many

ladies on board knew these women, and gathered round for the liveliest bit

of 'shop-talk' I ever heard. The sales were brisk, and as the time got

shorter the prices broke in an alarming manner. One American lady

evidently had been here before, and she knew the ropes. She had set her

heart on a lovely lace collar and cuffs, and fifteen yards of '

insertion,' whatever that may be. The Irish woman wanted £15, and would

not budge until the whistle blew, warning all to leave the vessel. An

officer was already coaxing off the women, and ours was the last to go. At

the last moment she said to the American lady,

'Sure I likes the look of your

lovely face, and it's meseif that has spicial raysons for wantin' your

money. I'll be afther takin' £3 10s., my lady, and by our dear Saint

Pathrick the price won't pay for pratees for the poor colleen that worked

it.'

"The lady had the

money ready in her hand, and the purchase was hastily concluded ; then the

lace-seller added—

'My lady, I sold that cheap to yez bekase ye

have the red hair, and sure it's meself will be

having a bit of luck to-day.'

'Now then, Mollie,' said

the ship's officer, 'you'll be off to New York in half a minute.'

'Arrah, now be aisy,' retorted Mollie, 'phat would

become of all the babies wid Mollie away?'

The gangway was already adrift when Mollie ran down.

She had to jump the last yard, and she fell all in a heap into her basket

of lace. It was a very near shave. As we sailed away the Irish

lace-sellers held up long pieces of lace and expensive shawls, and the

wind catching them made streamers of them. This was their adieu, and the

ladies who had been customers waved back again. For some time afterwards

the ladies could not resist the temptation to try on their purchases, and

when the gentlemen were not supposed to be looking the lace was held up

against their dresses in dainty festoons.

On fine days it is most exhilarating to sit on deck

protected from the keen winds with an overcoat and rug, reading, writing

home to one's friends, or perhaps building castles in the air of what you

will do at the end of the journey. And after all it does one no harm to do

a little building of this nature, providing the castles are designed

properly with the intention of serving as an incentive to greater activity

and more service to mankind; and not as castles of despair, or forts built

in which to conceal ourselves and all that is best in us. There is also a

fascination in watching your fellow-passengers. There was a fat, lazy,

'fetch me carry me ' sort of man, Captain Blank, who

always lolled the day long in his deck-chair full length, tucked in like a

child in bed on a winter night, while he left other folk to look after his

wife. Then there was dashing Captain Bland, who spent all his time in the

smoke-room. No game of cards for high stakes left out the Captain. Then

there was the fat man with a dark brown soft hat, down at the front and up

at the back, whose moustache is always brushed up. He is a German. He

wears his hairy decorations like his emperor, and the up-turned ends of

the moustache nearly touch his bushy eyebrows. He is calm and collected;

no bustle. He has been here before. He is going to America to sell Munich

beer. Then there is the gushing Miss Gosling. How 'chic' were all her

gowns! Her little red satchel matching her hat of the same shade. I know

her picture-hat was a dream! What rings! Two on every finger. I would not

wonder if she had rings also on her toes, lut of course we cannot enquire

too minutely. I can only guess by the way she waddled. Stout ladies, thin

ladies, tall ladies, short ladies, nice ladies and the other sort. The men

were also a mixture, but on the whole our fellow-passengers were a

well-behaved crowd."

"Strange to say, as we drew near to New York on that

Saturday morning and saw the huge piles of masonry, as the sky-scrapers

towered against the sky-line, the story of Gulliver amongst the

Brobdingnagians came to my mind. It was easy to imagine that we were

approaching a city of giants, and we felt very small in consequence. And

yet these great buildings, and all the wonders of New York which I was to

see later, were the result of the untiring energy of a people who were in

themselves as mere pygmies beside their giant works. Each country has

something to teach another. No one place has all the wonderful things. God

has blessed every nation, and as one trav1s about it becomes more apparent

that the various nations depend upon each other, and reciprocity is

essential for the good of the whole."

A second visit was paid in the

spring of the following year, and business began to assume a tangible

form. A consignment of toffee had been taken over on the first prospecting

tour, and the reports received were very encouraging.

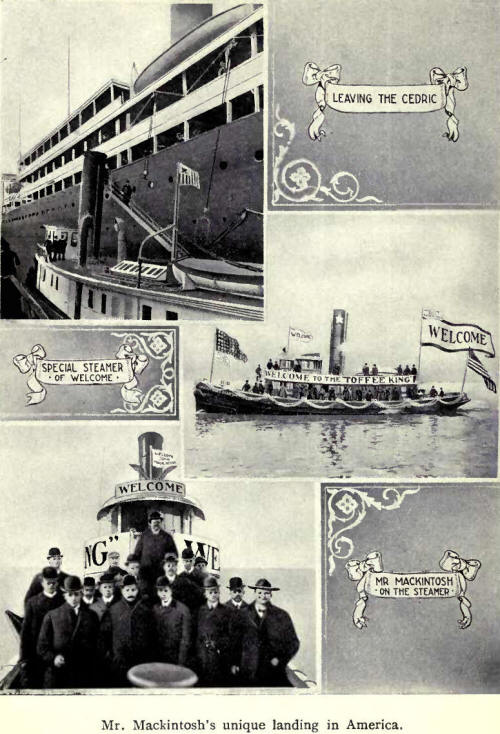

Mr. Mackintosh, himself an

advertising genius, had heard much of American enterprise in this

department, but it is certain that he had the surprise of his life as the

"Cedric" drew near Sandy Hook on the morning of April 15th. A tug-boat was

seen making out from New York harbour. The boat was gaily decorated with

flags and bunting, a huge Poster was displayed running from stem to stern,

bearing on both sides the words, "Welcome to the Toffee King." Monster

flags streamed from the mast-head bearing the same legend, and the Union

Jack and the Stars and Stripes floated side by side at the stern. On board

there were twenty or thirty journalists. As the tug-boat drew alongside,

the giant "Cedric" was hailed through a megaphone, and the captain was

informed that a special permit had been obtained and special Customs

officers were on board to take off John Mackintosh of Halifax. With that

the great liner hove-to the gangway was lowered, and Mr. Mackintosh in

much confusion and embarrassment made his way into the waiting tug-boat.

With syrens blowing, general commotion, and nearly two thousand passengers

looking on, this most modest and unassuming of men made his noisy, and to

him, most uncomfortable entry into the American business world. It was a

pure American advertising stunt. Photographs of the seen; together with

"An interview with the ' Toffee King,' appeared in most of the American

newspapers and magazines. Suppressing his annoyance, he smiled at the

authors of this novel advertisement. But he began to wonder, "If this was

a sample of American advertising methods, to what would it eventually lead

him?" Photographs of this incident are reproduced on another page. The

title of "Toffee King" was now given him everywhere he went in the United

States. It was the kind of label that delighted the American advertiser,

who revels in forms of advertisement that would be impossible, and even

resented, in our more sober-minded England.

Within an hour after landing in

New York Mr. Mackintosh was at his agent's office, formulating plans for

firmly establishing his business in the United States. The same night he

left for Philadelphia, to inspect premises that promised to be suitable

for a factory. During this period, and until the American factory was

running the toffee was imported from England, and the sale grew rapidly.

After a long search and many disappointments, a suitable factory was

bought at Asbury Park, a little sea-side town within easy distance of New

York. The factory was quickly equipped, and staffed partly by employees

brought over from the English works.

It was now necessary to create the

demand for his goods, and this Mr. Mackintosh accomplished in his own way.

Shops were opened in the principal cities throughout America. Samples of

the new English candy were freely distributed, and the goods themselves

were their best advertisernent. To an American interviewer Mr. Mackintosh

said "I build up my business by giving away my toffee. If I can get a

sample into the mouths of the people, I can safely rely upon securing a

customer."

Strange as it seems, however, the Americans were not

familiar with either the word toffee nor the article, except those who had

come across it in England, and these were eager to renew their

acquaintance with the well-remembered sweetmeat of earlier days. Canada

was much quicker in responding to Mr. Mackintosh's toffee crusade but the

genuine American had to be converted to the toffee-eating habit, just as

much as the Russian or the Dutchman.

Many unexpected difficulties were

encountered through the great climatic extremes between winter and summer.

In winter the toffee would keep well and command a large sale, the factory

being unable to keep pace with the demands of the trade. But in the hot

summer the goods deteriorated, and the Ice-cream shop and the Soda

fountain got all the attention. The trade dwindled to nothing, making it

difficult to keep the factory running and the organisation intact. The

long distances which the goods had to traverse also created further

difficulties. However, Mr. Mackintosh believed that 'difficulties exist to

be conquered,' and eventually he found the remedy and applied it,

producing a toffee that would keep in almost all conditions in any

climate.

By the time that the second visit to America ended

trade began to move steadily upward. He entered into large advertising

contracts, and soon his name became as familiar to the American as it was

to the Englishman. He had to lay aside some of his prejudices against

personal display, for in America the personal element counts for much. He

was induced to take his own photograph as his Trade-mark, an idea that he

would have promptly turned down in England. But he found that it was

common practice in the States, and as his agents pointed out, "Your own

face is the only thing that your competitors cannot copy." This photo,

with the label, "I am the 'Toffee King,'" was printed in every magazine

and newspaper throughout America. His portrait also appeared upon the

gable-ends of twenty-story sky-scrapers. At that time it was said that

Theodore Roosevelt and John Mackintosh were the most widely photographed

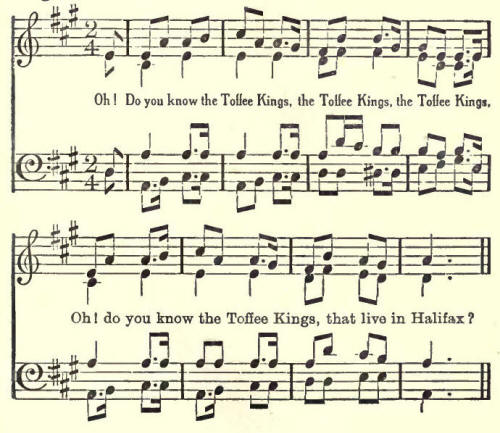

people in the United States. Music also lent its aid to the ingenious

American advertiser, and the following effusion appeared in the magazines.

Of the American habit of constantly chewing something

more or less spicy, he writes :-

I find the following notice in all trains and public

conveyances: - Spitting, five dollars.' I soon

saw the need of this caution, for the average American chews continually.

There was also a large poster asking all and sundry to 'Chew Bob's

tobacco.' Then, sad to relate, the ladies chew

not tobacco of course, but chewing gum. I was

shocked times without number to see most respectable and attractive

looking women and young girls spoiling all their natural beauty by chewing

gum as if their lives depended on it. I confess that later this habit gave

me some little consolation, for I thought if they will chew that stuff,

surely I can get them to chew my toffee."

Mr. Mackintosh set himself against the American

advertiser's habit of exaggerating and distorting facts, and it needed

constant vigilance on his part to keep his

agents within reasonable bounds.

Here is a typical piece of

American copy put forward for Mr. Mackintosh's consideration, but which he

turned down as being too far-fetched altogether but it is perhaps worth

reproducing for it will draw a smile from the reader, if nothing else.

"THE TOFFEE KING'S PROCLAMATION.

"I am John Mackintosh—The Toffee King— Sovereign of

Pleasure—Emperor of Joy. My Old English Candy—Mackintosh's Toffee—tickles

the palates of my millions of subjects. I was crowned by the lovers of

good things to eat. My Court Jester's name is Appetite. My most loyal

subjects are the dear little children. I rule over the Kingdom of Health

and Happiness. There is no oppression in my domain. My regime is one

of enjoyment and delight. My throne is guarded by an Imperial Unarmed Army

of Candy-makers. My coronation took place many years ago. I am an unusual

monarch—all my subjects are knighted. Those who become members of my Royal

Court must eat Mackintosh's Toffee at least once each day in the year.

"My recipe for the manufacture of

Mackintosh's Toffee is unequalled. My candy kitchen is the largest in the

world. Hundreds of tons of Toffee are sold each week in England. Think of

it! I am the world's largest consumer of butter. My own herd of prize

cattle grazing on the Yorkshire hills supply me with my milk. I buy sugar

by the train load.

"I have a legation in all parts of North America. Ask

your dealer for it. If he does not sell it, show him this decree. If you

will do this for me I will confer upon you the Order of the Milk of Human

Kindness.

I am,

John Mackintosh,

The Toffee King of

England,

and I rule alone."

Mr. Mackintosh kept this as an

example of what American advertisers would have done if he had let them

have their way.

While this work is in preparation, a copy of an

American Confectionery Journal comes to hand, containing a notice of Mr.

Mackintosh's decease. It is flamboyant and very American, but the

intention is wholly kind, so we give it here for the reader's amusement

and instruction in regard to journalistic methods out West.

"There are more ways of achieving

fame than by just getting

yourself elected President of a Republic, or throwing the plumber out on

his back and finishing the job yourself. One

only needs to go into the candy-making game in England. Old John

Mackintosh, J.P., of Halifax, knew considerable about candy. In fact what

he did not know about it you could load on a flea's back. He started

fooling with toffee when he was twenty-one, in a little kitchen, with a

brace of antediluvian frying pans that mother used to cook the rashers in.

But he was sound in the upper storey, with pints of business acumen, and

he cottoned on to advertising as a medium for business building, like a

coon kid getting acquainted with a water-melon, and so perhaps it is only

natural that John should build up one of the biggest candy businesses in

this little 'Old Island.' He was fifty-one when he passed on; he was

twenty-one when he began roasting sugar. So that left him thirty years to

do it in."

Shortly before Mr.

Mackintosh was to have embarked for England, on his second visit to the

States, he had a mishap in which he narrowly escaped with his life, and

from the consequences of which he never thoroughly recovered. He visited a

dentist who claimed that all his operations were painless. He thought he

would surprise his friends by returning home with a new set of teeth, but

the result was a surprise of a very different character. He was given an

over-dose of cocaine, and after returning to the hotel he was taken

violently ill. Fortunately his brother-in-law, who had arrived from

England a few days previously, was able to get immediate medical

assistance. It was only the fact that the skill of the hotel doctor was

available on the instant that saved his life. The issue was

doubtful for several days, and it was 'many weeks before he was so far

recovered as to be able to undertake the journey home. When he reached

Halifax again, after four months' absence, he was a very different man

from what he was when he left home. For twelve months he was an invalid,

and his nervous system had sustained a. shock from which he never

afterwards entirely recovered. This was the origin of the affliction from

which he suffered for the remainder of his life.

After resting for a year at home,

undeterred by this painful experience, he again visited the United States,

and subsequently he crossed the Atlantic every year for a long period of

his life.

Mr. Mackintosh was never so immersed in business as to

forgetre1igious and social claims. He was a sincere and enthusiastic

worker in the Church and Sunday school. On hearing him talk of his

experiences in America, the impression received from the drift of the

conversation, and the detailed information he gave, was that he had gone

specially to investigate the American Sunday school system.

Every

Sunday, when in America, he visited some Sunday school, occasionally

addressing the scholars, but always carefully observing the methods of

work adopted, and gleaning information that might be useful to the schools

at home. He promptly accepted unfamiliar methods when he saw that they

were successful elsewhere, and adopted them when they were practicable.

On one occasion, a business friend

invited him to a little town in the country, about fifty miles from New

York, and asked him to address the Sunday school on the following Lord's

Day. It was "Thanksgiving Day" in the States, and therefore a great day at

the school. When he arrived on the Saturday evening, he was startled to

see his name placarded in huge letters, together with the following

announcement:-

"JOHN MACKINTOSH, THE MILLIONAIRE CANDY KING FROM

ENGLAND, WILL ADDRESS THE SUNDAY SCHOOL ON THANKSGIVING DAY."

On reading this specimen of

American hyperbole, he was tempted to take as his subject

Truthfulness."But after a night's rest, recalling the fact that he was in

America, he submitted with a good grace, and spoke of "How to get rich by

giving things away." To illustrate and illumine his subject, he told the

following appropriate parable

"It was the eve of 'Thanksgiving

Day' in New York, and Mr. Brown was hurrying home from his office, when

passing a poulterer's shop he remembered that he had not sent the usual

'Thanksgiving' present to his cashier, Mr. Jones. So at the risk of

missing the last train home, he stopped and ordered a turkey to be sent

along to Mr. Jones' address. The turkey arrived somewhat late in the

evening. Mrs. Jones had given up all hope of the usual gift coming along,

and had therefore bought a goose for the occasion. Not wishing to keep all

the good things for herself, she passed along the goose to Mrs. Smith, who

used to come and help them with their domestic cleaning. When Master Jones

arrived at Mrs. Smith's with the goose still later in the evening, it was

only to find that Mrs. Smith had made a rabbit pie for their 'Thanksgiving

dinner.' But being touched by the generosity of Mrs. Jones, she racked her

brains to discover someone to whom she might pass on the rabbit- pie.

Eventually she thought of poor Joe who used to sweep the crossing on

Broadway, and she trotted off to his wretched attic with the rabbit-pie.

On the morrow what was left of the rabbit-pie was given to the birds, so

they too had their 'Thanksgiving' feast. And so quite a lot of different

people were made richer and happier by Mr. Brown's first gift."

On another occasion, being in the

West End district of New York, he was attracted to a palatial Sunday

school, and entering with the others, he found himself occupying a front

seat in a large Bible class for adults. The teacher, who was quite a young

man, took the whole of the service, and expounded the lesson quietly but

clearly, and with just that touch of feeling that made it effective. Mr

.Mackintosh was afterwards invited to meet the teacher, whom he

discovered, to his surprise, was the son of Mr. Rockefeller the "Oil

King." Young Mr. Rockefeller was naturally pleased to show an enthusiastic

English Sunday school worker all the machinery of an up-to-date American

school, which never had to wait for what was requisite for lack of funds.

The next morning a New York paper

contained the following item of information in a report of the meeting of

the Bible class:- "The usual detective sat on the front row of the class,

who afterwards joined Mr. Rockefeller in the vestry." So for once an

American reporter was caught napping.

Among other well-known Sunday

school workers whose acquaintance Mr. Mackintosh made during his travels

was Mr. John Wannamaker, then the greatest shop-keeper in the world.

They met at a Sunday School

Convention, and Mr. Mackintosh asked Mr. Wannamaker to write and send a

message to Sunday school workers in England. Mr. Wannamaker promised to do

so, and said that he attended Sunday school every Sunday morning. Shortly

after Mr. Mackintosh's return home he received the following interesting

communication from Mr. Wannamaker:

"I take pleasure in affirming my

belief that the bet expression of God's love to men is the cross of Jesus

Christ, and the fact that there are three sure roads that lead straight to

it:—the Sabbath, that God made for man; the Book of God, to be man's lamp

; and the Sanctuary, to be God's schoolhouse. Scientic enquiry has done

much to bless the world, but no discovery it has made can help men so much

as these three paths. JOHN WANNAMAKER."

But Mr. Mackintosh never forgot

Queen's Road Church and Sunday School wherever he might be, and on Sundays

his thoughts were always drawn to the place which had for him so many

tender memories. Here is a typical letter home

Sunday, May 8th, 1904.

To-day is the first Sunday in May,

the Sunday School Anniversary, It is about 2 o'clock by American time,

about 8 o'clock in the evening by English time. You will be just singing

the last hymn at the evening service. My mind conjures up the scene of all

the happy children arrayed in their Sunday best, now getting rather tired

but still singing lustily; and the fore-gathering of so many old friends

and scholars. How I long to join in singing that hymn! I am far away here

in America, but wherever I go, and whatever new scenes I see, or people I

meet, nothing takes the place, or is more beautiful, than the old place

and the old friends at Queen's Road. No business nor worldly success can

holdout such pleasures as these."

The overflowing good nature of the

man was evident in the trouble he took, and the time he spent, looking up

relations of friends at home who had removed to various parts of America.

Nothing delighted him more than to visit them in their homes in the new

world, no matter how. humble they might be. He was always welcome, for the

prosperous business man was the unchanged friend whom they had known in

former years.

When he was in Philadelphia he visited the grandmother

of one of the Queen's Road girls. When he arrived at the house the door

was opened by the old lady herself.

His greeting was—

Are you Nellie's grandmother?"

Without asking the name of her

visitor she replied—

"Aye, lad, I am; come reight in."

He followed her into her

spotlessly clean and tidy kitchen. Then without speaking another word, she

drew a big chair to the fire for him, placed the kettle on the hob, spread

the white cloth on the table, got out the tea things, took off her apron,

and sitting down in a chair by the hearth, she said in the broad Doric of

her native county—

"Well, lad, I dunnot knaw who tha' art, but if tha'

comes fra' Halifax tha'rt reight welcome. Eh ! but tha' knows I left mi

heart i' Queensbury."

Queensbury is a small township perched on the Yorkshire

hills a short tram-ride from Halifax. It was sweet to hear the familiar

dialect and to receive such a hearty and homely welcome, and Mr.

Mackintosh felt repaid for all the trouble he had taken to visit the old

exile from home.

Another touching incident occurred during this tour.

Two factory girls who hailed from Halifax saw him passing through the

works where they were employed, but they were afraid to speak to him,

"because he was with the 'Boss.' " These exiles were so bitterly

disappointed that, as they afterwards said, they went home and "had a good

cry." When the circumstances came to the knowledge of Mr. Mackintosh, busy

as he always was, he found time to write them a personal letter expressing

his regret that he had missed seeing and speaking to them, and promising

to call at their home and have a chat with them on the first opportunity

that occurred. He kept his word, and for a short time they had him all to

themselves, to their boundless delight. There are few among the great

Captains of Industry who would take so much time and trouble simply to

cheer the lonely hearts of two poor working girls.

Of the American in some businesses

he says:

"I came across some delightful people. Of course most

of them hang on like glue if there is any money about. I mean business

people; for out of business hours the American and his lady are the soul

of good fellowship, and generous to a degree; but during business hours

they are on the dollars and no mistake. "

He told a delightful tale of an

American lawyer :-

"Our lawyer is a splendid man, quiet, unassuming, never

mentions money, will smoke a good cigar with anyone. One evening I invited

him down to my hotel to join me at dinner, and afterwards for cigars.

There was a magnificent orchestra provided by the hotel, and we had a very

pleasant evening. On leaving, the lawyer remarked, 'Well, Mr. Mackintosh,

it was very kind of you to invite me down here. I shall not forget your

splendid hospitality. I want you to come up to my club on Saturday

evening, and I shall be delighted to play the host.' I accepted the

invitation. But when the next bill came in for services rendered by the

lawyer he charged in full for that banquet, even to the tips he had given

to the waiters, and for his time in attending my little party. Smart, was

it not? But then we must not judge the average American by the smart New

York lawyer, and I have many good friends, and most delightful

remembrances which linger, and always will, in my memory."

Among the sights of New York Mr.

Mackintosh was induced to visit China Town.

I was indebted to a business

friend for some of the strangest sights I ever saw. He was anxious that I

should see Chinatown at nighttime, for then they are seen at their

liveliest, as they sleep during the day and work or play at night. We

arranged a meeting place, which was none other than the Police Office

nearest the Chinese quarter. Here our friend arranged for a detective to

accompany us. We noticed that his pocket bulged out to a considerable

extent and decidedly took the shape of a revolver. Eventually we ran full

tilt into Chinatown. Here was to be seen, a whole street of genuine

Chinese, with sleepy eyes, and wearing queer shoes and clothing, and with

black pig-tails hanging down to their ankles. The shops were all Chinese,

from the names on the doors to the men behind the counters. It was the

queerest place imaginable, and one forgot one was in the heart of New

York. We felt rather creepy as we elbowed our way through the crowds of

these sleepy Chinamen. Some would say things to us which we could not

understand, others looked round at the inquisitive infidels that were

invading their territory. We visited first the 'Joss House,' the Chinese

name for their temple. This was at the top of a three-storeyed building,

and the temple was more like a show at the Halifax Fair than anything

else. Faded tinsel trimmings, rusty ornaments, worm-eaten Oriental rugs.

The altar where the people knelt to pray was a dirty, dismal affair, and

the gods were dirtier still. We did not remain long, I assure you, and the

visit, I am sure, did not convert us to Confucianism."

"We next went to the Opera House.

This was a large building, again reminding one of the wooden shows of the

fair-ground. We paid our seventy cents and entered. We had a box reserved

for us. This was nothing more than a bench on a raised platform with a

wooden railing. From our 'box' we saw a thousand sleepy eyes staring at us

out of expressionless faces. We wondered if they liked us coming into

their places of resort, out of mere curiosity. We looked cheerful and

talked to one another as if we owned the place, but I believe most of us

were chicken-hearted. What a strange sight is a Chinese play A Chinese

actress was on the stage. She was slowly moving her body to and fro,

raising her hands slowly, and slowly letting them fall again. Her slow

sing-song was very little better than a cat's concert, and not half as

exciting. Every now and again she clutched an imaginary object, supposed

to be a bird or a fly I should think, for after pretending she had caught

it, she would lift it out of her hand and let it fly away again. These

movements would continue for nearly an hour together. Of course they were

accompanied by musicians of the Chinese variety. The music was similar to

what we have heard many times from a boy's impromptu band, furnished with

such instruments as an empty can, the bottom of a tub, and a comb. We

endured it as best we could. It was truly novel, and if it was not to our

taste it gave us a very good idea of the things that appealed to the

people in far-off China. Our guide told us that all Chinese plays are

historical, and as they often last for many weeks, the Chinaman has to do

a lot of reading of his country's history to understand the meaning of the

play. The large audience never took their eyes off the players, and seldom

was any expression seen on their faces. Now and again some special point

of interest sent the ghost of a smile across their faces, only to be

immediately lost again.

"After leaving the Opera House we

followed our leader down dirty alleys, mounted a flight of steps, and went

along a passage that contained the accumulated dust of years. A door was

opened in answer to a regulation knock on the panel, which was understood

by the door-keeper. What a sight met our eyes as we entered! We were in an

opium den. On beds of straw round the room men were smoking the poisonous

opium. What a sight! Some of them had been imbibing the fumes of the

deadly narcotic until they were in a state of unconsciousness; with glassy

eyes, drawn faces, clutching nervously at their pipes with the long stems

and small heads and so they dreamed and dreamed while their bodies were

going to the grave. The abominable stench of the whole place was turning

me sick.

Our next visit was to a Chinese

Restaurant. For Chinese it was clean. It was well fitted up, but, of

course, in the Chinese fashion. A fussy little Chinaman brought us the

menu. We first had some real China tea and some chop-sewie; or, rather, we

ordered it. Do you think we ate it? If so, you are mistaken. Had we not

still the smell of Chinatown in our nostrils? No we paid for supper, but

personally I had no appetite for anything to eat for hours after I left.

It was in the early hours of the

morning when we at last left Chinatown behind us. For days after these

sights haunted me. I am not quite sure whether when I got into bed .I did

not pull the clothes up higher than usual. I know I was glad I was born in

England and am an Englishman.."

Mr. Mackintosh was in the States

during one of the Presidential elections. Of American politics at that

time he says :-

"There are scarcely any

independents in the States. Either you are a Republican or a Democrat. The

method adopted by each side working for votes is, first to look up

carefully the records of the opposing candidate or any of his chief

supporters, then to circulate all the stories they can possibly

manufacture about them. If such language were used in England I am afraid

there would be many libel actions, but here it is the man who can do most

damage to the other man that wins. One side is represented by large

posters as being a tiger ready to tear the country to pieces. In great

letters under the picture of this tiger appear the words, 'Do you want to

let the tiger loose again? If not, vote for John Jones, who drew the

tiger's claws.' In a shop window on one of the main streets of New York

was a great cage with iron bars. Inside the cage was a huge tiger pacing

restlessly. A placard contained the words, 'Do not let the tiger loose

again!' In another part of the window was a tray full of tigers' claws,

and the injunction to, 'Vote for John Jones, who pulled these claws at the

last election and will do it again."

This is what Mr. Mackintosh has to

say of his first view of Niagara:-

"As one looks at this mighty mass

of water as it thunders over the ,precipice, the sight grows on one and

you feel Niagara. There is always a great cloud of mist rising in front of

the falls, and as the sun shines through it the most perfect and beautiful

rainbows form. With every changing light the falls present new beauties.

Now the waters are green as grass : then in the shimmering light, silver ;

again, they are as black as ink. As you look intently into the spray

flashing back the light you can see angels dancing on the waters; or if

you are in a despondent frame of mind, you may see chariots, with demons

driving black horses to the bottomless abyss. You feel you want to laugh

and. sing one minute, and the next to sob I At one time you think the

river belongs to God, and the next it seems too terrible, and must be the

work of the devil. Here on the Canadian side is a 'Cliff Railway' that

takes people down below, and enables those who are hardy enough to go

right under the falls themselves. We were quickly accommodated with

water-proof suits, and a guide accompanied us as we descended into the

depths below. The roar of the falls from above was as a whisper compared

with what we now heard, as we crept along the foot of the precipice

towards the cave through which we were to go a hundred feet behind the

terrible falls. We found the need of the waterproof clothes very soon, for

the wind moaned and groaned and blew the spray over us, making us dripping

wet. We 'felt Niagara' now in more ways than one. It was easy to imagine

ourselves one of Dante's party, as we followed our guide over the rocks

and across the abyss, on the way to the land of lost souls. As we entered

the cave, even the small light we had failed, and our guide picked up a

lighted lantern and led us on. The only possible way to see the falls is

to approach them from the cave.

"When a good distance in we came

to a hole in the side of the rock, and we approached tremulously and

looked out. A great gust of wind sent the spray into our faces, and we

stepped, back gasping for breath. Still, with the water streaming from our

oilskins we go on, until the cave suddenly opens and we are in front of

strong protecting rails. So far and no farther! There is no need for

warning notices. Ten thousand lions in our path could not be more terrible

than this fall of water. All the beauty is lost in the terrifying

spectacle! You feel your flesh creep and the hair on your head rise. I

hear that sometimes people looking on Niagara lose their reason and jump

into its terrifying depths and now, after seeing it from beneath, I have

little wonder that such strange things should happen. This experience is

fit only for people with strong nerves. To those who can stand the test it

reveals another world. We presented a sorry spectacle as we ascended,

dripping wet and begrimed with clay, but in a few minutes we were in our

carriage, dry and happy once more."

Of the dangers of New York he

writes home:-

"New York is the noisiest city in

the world, and yesterday I was reminded that this is a land of risks. I

travelled on the railway over a spot where an accident happened an hour

later, several being killed. I crossed the river in a large ferry-boat

half an hour before a serious accident had happened to one of these boats,

through the man at the engine dying suddenly at his post. I was passing

down Broadway later in the day when a man was run over by anelectric

street car and killed, and when I got nIcely to bed at night I was

awakened with fire-engines flying through the streets ; a great factory

was burnt down to the ground, and many firemen were killed. I am, however,

missing all these things, and I am glad to say I am keeping very well."

The Notes contain an account of

Mr. Mackintosh's unpleasant experience in a terrific blizzard. He was

returning from Montreal to New York, with just sufficient time to complete

the journey and catch the Liner home, when the blizzard overwhelmed the

train, and after struggling many hours to get through they were completely

snowed up. Help was obtained, and after immense labour the drifts were

sufficiently reduced to enable the train to be moved to the nearest

wayside station, where it remained for forty-eight hours, until the

blizzard had blown itself out. On arriving at length in New York three

days late, the Liner had sailed, but he was able to book a passage on

another boat the following day. Early on the voyage an incident took place

which he used subsequently as an illustration in his addresses.

"Some twenty-four hours after

leaving New York we were at breakfast, when suddenly every passenger on

the ship was aware that there had been a distinct change in the throb of

the engines. People stopped eating and looked wonderingly about, for it is

an almost unheard of thing for those mighty engines to cease their steady

throb when once the vessel gets under weigh for its three thousand miles'

trip. Another minute or two and the engines ceased altogether. That was

too much for the composure of even the most experienced traveller, and

within two minutes the dining-room was deserted, and all the passengers

were out on the decks. Seeing nothing, all eyes were turned to the bridge,

where the captain was looking anxiously through his glasses. Over two

thousand pairs of eyes followed the direction of the captain's search of

the ocean, and there, sure enough, could be seen a small object on the

water about a mile away. Eventually it turned out to be a raft, on which

were what remained of a ship-wrecked crew of a small schooner. As the ship

came near the raft the life-boat was lowered, and two men, a woman and a

little child, all in an exhausted and almost dying condition, were brought

aboard the vessel, the raft being allowed to drift away after having done

its work. It turned out that this little schooner had been caught in the

same blizzard that had held our train up some days previously, and these

were all that were saved, the woman being the wife of the skipper. It was

great excitement for all on board, and we all felt somewhat proud of the

rescue, as if we had had something to do with it. I could not help

thinking how sacred human life is; for had that raft contained only one

little child, perhaps only a few days old, yet this mighty vessel with

thousands of souls on board, which in the ordinary way nothing could ever

have induced to alter its relentless course, would have stood away and

spent hours, if need be, in the rescue of that dying baby. This is just

what our Sunday schools and kindred institutions are striving to do—to

save the children and put their feet on the safe and sure path. Can any

work be more worthy pf man's endeavour? I think not!

|