|

There is a science of advertising

as there is an art of speech. It demands a wide know.- ledge of human

nature and the ability to see things from the average man's point of view.

Referring to an advertisement in which it was proposed to introduce a

slang sea-term, Mr. Mackintosh wrote to his advertising agent to the

following effect:- "The term used, I fear, will

not be understood by ninety-five out of a hundred of those who read it,

and I never think it is good advertising to mystify the crowd in order to

prove oneself smart to a handful of people. I never heard the term used in

that connection, and I am sure I am one of a great crowd."

He saw the advertisement from the view-point of the

man in the street, and he resolutely eliminated everything that might

confuse or mislead.

The

various schemes and novel methods of advertising previously recorded,

having served their purpose, gave way to more solid and scientific

publicity. The trade announcements of few men have appeared more

constantly in the British press ; the press was his pulpit, the world was

his parish, and his text was ever the same, "A pure and wholesome

article." He was best known and will be longest remembered as a great

Press advertiser on a national scale. He always gave his personal

attention to the drafting of his advertisements, and one cannot do this

for thirty years without one's personality being seen through them, any

more than the novelist can continue writing

without his or her personality appearing.

Mr. Mackintosh's advertisements,

like the man himself, were direct and honest, with natural and homely

appeals by picture and text. He disliked advertisements which were mere

displays of cleverness. " When I read a fancy phrase" said he " I know it

is just put there to tickle my mind, and I discount it accordingly."

Natural shrewdness, allied as it was in him to great human kindness,

always led him along right lines. He believed that a straight story was

the only lasting form of advertisement. He did not regard the general

public in the mass, but rather as individuals who might become real

friends. This was a prominent trait in his character, and many of his

announcements were addressed to "Lovers of Toffee de Luxe," in whose

friendliness he had a general belief. He created the "De Luxe Family." He

was not content with one member of the household to typify his public, but

created the whole family from 'Grandpa' to 'Babs

truly a wide appeal, since all humanity is included in the family circle.

Discussions on plans to be adopted were invariably

prefaced by this remark from Mr. Mackintosh "Now let us talk round the

subject for a bit, before we open out these schemes." The papers were left

unread until the policy to be adopted had been settled. The draft schemes

were considered, and modified, if necessary, by what had been learnt in

the talk round the subject.'

He had ideas in abundance. Little time was lost in

searching for them; much time was spent in deciding which of several was

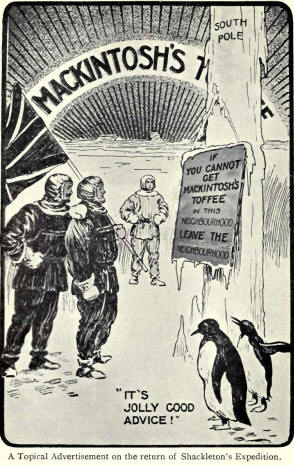

the best. On one occasion he and his advertising agent were going over

some advertising material, and were searching in their minds for a

suitable reply to the question, "If you cannot get 'Mackintosh's Toffee'

in your neighbourhood, what should you do? "The

solution came from Mr. Mackintosh with his usual clearness and directness,

"Leave. the neighbourhood!" There was a pleasing touch of humour in the

answer which made it very effective.

Shackleton hadjust returned from

his exped- ition to the South Pole, and the great explorer had taken a

case of "Mackintosh's Toffee" with him on that perilous journey. A

pictorial representation of Shackleton's expedition was at once issued. It

represented the crew with their sledges and dogs in front of the Pole, on

which was fastened a notice, "If you cannot get 'Mackintosh's Toffee' in

the neighbourhood, leave the neighbourhood." Two excited penguins were

flapping their wings and responding "Jolly good advice, too."

On the other hand, there must be

some similitude between the means used to advertise and the article

advertised. Mr. Mackintosh declined an advertisement which made a tin of

toffee into a tank. "There is no connection," said he, "between 'Tanks'

and shooting and 'Toffee de Luxe,' and everybody knows it is a fake or

make-believe."

He habitually used the full-page pictorial

advertisement in the daily press, particularly the front page of the

"Daily Mail" and other London daily papers. His views of this form of

advertisement were set forth in a series of " Talks to the Trade," that

is, to the tens of thousands of shopkeepers with whom he did business.

Here is his own candid statement of the comparative cost of newspaper

advertisement, and of the same amount of publicity obtained by private

means.

"The whole front-page of this newspaper is one of the

most expensive advertising spaces in England to-day, if you look at it in

the wrong way ; but it is the cheapest way of sending you our message if

you look at it in the right way. The net sales of this paper to-day are,

say, 1,000,000 copies, and the advertisement rate for a front page is £350

[this was pre-war—Ed.] To post a similar number of copies of this

advertisement to both trade and public would cost:

Printing, cost of envelopes,

addressing, despatching, &c. £1,700

Postage at one halfpenny each ...

... £2,500

Total ... £4,200

So you see we are going the

cheapest as well as the quickest way to work."

The newspaper proprietors were so

greatly impressed with this plain statement of fact that they spent

thousands of pounds in reproducing the page, coupled with an announcement

of their own. It appeared in almost every newspaper in the United Kingdom

during the following week. This is a fair example of his directness and

honesty of purpose, which won for him, in the end, the confidence of both

tradesmen and the general public.

During the Great War the

Mackintosh advertisements were naturally of a topical character, and were

amongst the best that were issued in those dark days. He had powerful

drawings of scenes from the front executed by clever draughtsmen, showing

how "Mackintosh's Toffee" helped along "the weary hours with leaden feet,"

which moved so slowly in the muddy trenches or on the stormy and

treacherous seas. Innumerable suggestions for advertisements were sent to

Mr. Mackintosh across the seas from our men on the various battle fronts.

The work helped to pass many a tedious hour, and all these efforts

depicted the many good and varied uses to which the fight- ing men put

both the toffee and the tins.

In the autumn of the year 1914,

when the first hundred thousand of our heroic soldiers, the "Old

Contemptibles," were fighting with matchless courage, resisting the German

invasion of Belgium and France, a full-page advertisement was issued which

was very effective. The Kaiser is standing astride the maps of Belgium and

France and staring with angry eyes across the Channel to the British

Isles, on which rests a monster tin of "Mackintosh's Toffee." The title

gives the explanation, "So that is what makes them fight so well".

One of the Halifax soldiers on

being asked to describe his sensations when he first went over the top,

replied that "All he could remember was that he was eating 'Mackintosh's

Toffee.'

A few days before Mr. Mackintosh died, one of the

periodic round table conferences was held to consider advertisement plans.

The founder of the firm had written its history, and the rough draft was

typical of the man, full of homely touches and genuine good nature. It was

a plain story and an honest one, with his individuality stamped on every

line. Within a few days the last call came, and that " copy" became a

self- written obituary.

In the advertising world it has

become historical. It is his final message, and it was printed in almost

every daily paper in the United Kingdom; the papers chosen being these

which he was accustomed to use for advertising purposes. Probably never

before has anything been attempted on the lines of this memorial page, and

it involved a question of some delicacy. Only the fact that Mr. Mackintosh

had written it himself for advertisement purposes immediately before he

passed away, and that it had the particularly friendly and personal touch

to which the public to whom he appealed had become accustomed, made the

publication possible. It violated no canon of good taste, and it was

fitting that the great advertiser should deliver his last message after

his lips were silent for ever. "He being dead yet speaketh."

We reprint, by the kind permission

of the Editor of "The Daily News," an article contributed to that paper on

his experiences as an advertiser :-

"When I hear anyone speak of

business opportunities my mind goes back to early days, for if the long

road of business effort has led to success, it is pleasant to go back and

ponder over the faint and doubtful footpath in which it began. There is a

lesson in it somewhere for other young business men; and in my case I

think the lesson is the importance of small beginnings. If they are right

beginnings, they are valuable as gold-dust; if they are wrong they lead to

certain disaster.

I thought in those early days the

people wanted something else than the rather ordinary sweetmeats common at

that period, and presently the first business opportunity revealed itself

to me in the shape of an idea that toffee, made of ingredients that should

be scrupulously good and pure, was one of the things that the public would

take to. So I began to make it.

"Having made it I lost no time in

advertising it. In those days, to advertise a simple thing like toffee was

considered very adventurous, even presumptuous, but there is nothing so

simple that it is not worth advertising so long as it is good. Thus out of

the first business opportunity represented by the little advertisement in

the local paper his grown up a national industry in a national sweetmeat.

That little advertisement was a right beginning, which has landed us on

the high road to success.

"We nibbled at space at first.

Then we found our sales increasing, and we took larger spaces. Always the

sales grew with the advertising, until we were able not infrequently to

employ what is perhaps the most expensive, as it is certainly the most

remunerative advertising in the world—full pages in the London daily

newspapers.

"The young man in business may

possibly sigh when he reads about such spaces as these, and regard them as

things beyond his dreams; but experience suggests that if one could live

one's business life over again it would be better to get into one's

advertising stride as soon as possible.

"The Art of Advertising can only

be learnt slowly over a number of years. It is best to begin in a very

small way using advertisements put together yourself. I would rather make

a mistake now and again, and do it myself, than I would take blindly the

suggestions of even the greatest expert in advertising, because if one is

going to advertise properly and profitably one must do it for a lifetime.

And therefore, to get even the best out of the expert, one must have real

first-hand personal knowledge. And I don't say this to belittle the

Advertising Expert. The best of them will agree, I know, when I say, no

better advertising can be planned than that which has received careful and

intelligent criticism from the man who is at the head of the business

whose special goods are to be advertised, after the necessary knowledge

has been gained by the issuing of one's own advertisements. Then if you

can afford it, call in the 'Advertising Agent,' and put your heads

together, and things should improve all round. Sometimes when my agent

makes a really good suggestion, I let him work it out without much

interference, for a man's a fool, however much he knows about advertising,

if he gets it into his head that no one else can ever have a better idea

than his own.

"The question is, how just to

carry one's personality into one's advertising, without other people

discovering the individual in it. The biggest mistake I ever made in my

advertising was through taking the advice of an expert before I had myself

had sufficient personal experience to know if the advice was sound.

"But these are problems that come

later. The important thing is to begin well, and the great principle for

beginners is to get a thorough grip, of the value of small profits and

quick returns. In our early days we found that a thousand retail shops

selling our toffee, gave us a better return in profits than a much larger

margin on the sales at our single shop. It would puzzle a mathematician to

worry out the microscopic profit we receive from the weekly purchases of

Mackintosh's toffee by any one retail confectioner. But there are

thousands and thousands of these retailers throughout the length and

breadth of this and other lands, and this multitude of small decimal

profits, quickly gathered in week by week, makes business remunerative.

That is the secret of most of the

things which one sees advertised day after day. Those businesses have been

built up on the basis of small profits and quick returns, which

advertising makes possible.

"I attach such importance to

advertising that when I have once adopted a medium for my appeals I very

seldom drop it. Having gathered round him a public, which is what the

consistent advertiser does, he should never neglect it. That is why you

find our advertisements month after month and year after year, in times of

peace and in times of war. We know we have a clientele amongst our readers

because they write and tell us so. Nearly every time we insert a more than

usually striking advertisement, readers write complimenting us upon it,

sometimes offering friendly suggestions how it might be improved. I could

fill a column with extracts from such letters—from doctors, ministers,

business men, workmen, teachers, and school-children, all voluntarily

written.

"Only the other day a schoolmaster

in the South of England wrote us saying he had given one of our full-page

advertisements to his class as a drawing lesson. He forwarded half-a-dozen

copies of the boys' work.

"These things are worth

mentioning, because the extraordinary scepticism of small traders, and

some big ones too, about the value of advertisements is one of those

factors in British commercial life which pull it back. Every large

advertiser has facts such as I have given, proving incontestably that

advertisements are studied and responded to with marvellous swiftness and

volume. Little incidents like the schoolmaster's letter are valuable

because each one stands for an immense number of others which occur

silently. One man who writes represents hundreds, upon whom the same

impression is made, who do not write.

"So, if I were asked what is the

best business opportunity the trader, great or small, can have, I should

point to the advertising. This secures more customers at a stroke than any

other means open to him; and every customer thus secured, provided the

article advertised is a good one, becomes a missionary for it. He has

proved that what the advertisement said about it is true. He has come to

believe in the advertiser and trust him; and just as he will go out of his

way to say a good word for a friend whom he has learned to believe and

trust in, so he will be glad to do the same for the subject of the

advertisement that has gained his confidence."

|