|

"I

determined to bring London to our way of

thinking."—John Mackintosh.

One never thinks of Mackintosh without thinking of

toffee, and one never thinks of toffee without thinking of Mackintosh.

This is what thirty years of consistent advertising on a national scale

has done. Here we have, a man who thirty years ago saw his opportunity and

seized it.

In any account of

his business life it would be impossible to ignore the origin and

development of Mr. Mackintosh's genius as an advertiser. It must

necessarily form an important chapter in this book. The publicity side of

any business is the visible sign by which it is known to the general

public. It is the mirror in which the man behind the advertising is seen.

Although Mr. Mackintosh had a great belief

in advertisement, he attached still greater importance to the

quality of his goods. That thought was always

first in his mind from the very earliest days to

the end. Nothing was allowed to interfere with

it, and it was because he put quality before

advertisement that his advertising was

productive of such good results. His views on

this subject were given with some fulness

of detail, to a gathering of business men in the

following address on 'Advertising':

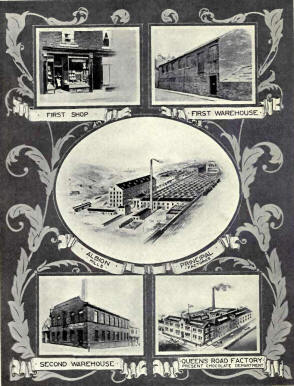

"I advertised on the day that I opened my

first retail shop in King Cross Street. It was

in a part of the street that was neither in the

town nor out of it, usually a very awkward

situation for a retailer. Shops round about were

changing hands rather often,—not a good sign. I

stood outside the shop and watched the people go by; I counted two

thousand in a certain period of time, that passed my door. I figured out

how much I should draw if twenty five per cent, of them could be got

inside to spend a few coppers each. Then I planned an advertisement to get

them in, and I don't think there was a more crowded shop on a Saturday

from King Cross to Baruth Top. Of course it was for small purchases, but

the 'little and often' adds up.

"Any one who can remember King

Cross Street on a Saturday thirty years ago will know that there was a

constant stream of people passing, mostly from Sowerby Bridge and King

Cross. Nine out of ten came down my side of the street, the left-hand side

going down.

"I tapped these people at the source and sent handbills

round Sowerby Bridge, choosing Friday or Saturday morning for the

distribution, so that the bill contents would be fresh in their minds. Of

course the local newspaper advertising was bringing people from other

parts of the town as well. Most business men have had experience of that

disheartening moment when little alterations in the manner of dealing with

transit upsets one's business apple-cart. The twopenny bus did it with me.

Up to this time everybody walked, but the advent of those sumptuous,

smooth-running.(?) vehicles, Marsh's 'buses, took everybody off their legs

as it were; and, if I remember rightly, at twopence a time. How the people

did go for those 'buses'.

"I could see them riding by, and

my takings fell off twenty-five per cent. As Saturday was worth all the

rest of the week put together, the loss of trade was considerable. I did

not shut up my shop. however I simply went after them, and opened a branch

shop in the market, and made an arrangement with a shop at Sowerby Bridge

to sell, and so I did more business than ever. This was all very well so

far as it went, but it did not satisfy me. I felt more cut out for

manufacturing and selling on a bigger scale.

"I argued that if people came to

my shop I could get them to go to shops nearer to their own home by

advertising. So I had the shopkeepers of Halifax called upon, and nearly

everyone bought a little, and I sold more goods than ever. But I quitted

my own retail shop, because people would not come out of their way to my

establishment when they could buy the same article at the same price in

their own street. I sold out and became a manufacturer only, and have

remained one ever since.

"At that period I began to broaden

out my advertising, taking in such papers as the 'Yorkshire Evening Post,'

for we were developing business in neighbouring towns. We had many

heart-breaking experiences. We were up against competitors who knew the

game better than we did, and would have been glad to see us go under. Of

course we always respect honest competition and could relate many

instances in which we have benefited by such competition, as doubtless

others have done.

"I was already getting wise to what was wrong with my

business. If I wanted to keep it from those who would have stolen it if

they might, I must do more advertising and so make the public my

body-guard as it were. I had by this time the country sufficiently worked

to warrant me in coming out with a national advertising scheme, but only

on a moderate scale. I consulted an 'Advertising Agent,' who represented

one of the oldest advertising houses in England. They have been agents of

mine ever since. We decided that magazines would suit my purpose, as I

could get into the leading magazines with the appropriation I was able to

spend, and they circulated everywhere. These advertisements had a very

good result, but there was some leakage, as we had not yet worked the

South Coast towns, and above all, London was the great unknown so far as

'Mackintosh's Toffee' was concerned.

"I DETERMINED TO BRING LONDON TO

OUR WAY OF THINKING, and. I appointed a good man and did some hard work

for a year, calling upon wholesale dealers only. At the end we were no

further forward, and yet I knew that Londoners were asking for the toffee

at the shops, for we were putting out feelers in that direction.

"At the end of the year I

instructed our London man to cease calling upon wholesale dealers, to open

an office and depot in the City; then to put an advertisement in the

'Telegraph' for commission men, who would sell the toffee to shops for

cash against goods. We got fifteen commission salesmen who set to work at

once, calling upon the retailers and selling for cash on delivery. The

salesmen posted their orders to the depot each night.

"Orders grew until we had

thousands of parcels disposed of regularly. At the end of the year we did

business with most retail confectioners in London, and we got a reputation

for prompt delivery. We had also every wholesale dealer we wanted. It was

surprising how interested they became in our goods after we had captured

the retailers. Our depot grew until it was a very respectable size, with

its own motor delivery vans and numerous travellers and commission

salesmen. Later similar depots were established in all the largest centres.

It was not until I got London that I Was able to get every ounce of value

from the national advertising we were doing. It is never wise to push on a

great advertising scheme until the whole of the ground your advertising

covers is worked and the goods are obtainable."

Such is Mr. Mackintosh's own

account of his first adventures in advertising. Advertising is to business

what romance is to literature. In both, imagination, originality and

courage are essential. With his fertile brain, and a new field before him

which was all his own, it was natural for Mr. Mackintosh to rise to the

first rank as one of the world's great advertisers.

Thirty years ago the consumption

of sweet- meats was for the most part limited to children•; they were the

toffee manufacturers' best customers, and his appeals were chiefly

directed to them. Now, that generation of young people has grown up, and

its love for 'Mackintosh's' has grown with it. Advertising cannot always

complete its aim in a few years, but may take a generation to materialise.

Mr. Mackintosh's first outstanding

adventure in advertising was a great prize scheme which at the time was an

absolute novelty. This was a competition for young and old, with no limits

for age or distance within the United Kingdom. The chief prize was a model

cottage valued, at the time, at £250. Coupons from packets of toffee had

to be collected and sent to the firm. There were hundreds of other prizes,

increasing in value according to the number of coupons gathered. The most

successful competitor, an Irish lady, had almost enough useful articles,

won as prizes, to furnish the cottage. Mr. Mackintosh learned from this

competition that such schemes have the great disadvantage of disappointing

so many entrants that they make more dissatisfied people than actual

friends. He avoided this mistake in his next venture by an ingenious and

amusing arrangement, as the reader will presently discover.

This was a Scholarship

Competition. Large spaces were taken in many of the great newspapers,

setting forth the conditions of the competition, which was open to all

children. The announcements were addressed chiefly to schoolmasters and

parents, and they were asked to get the little folk to send to the firm a

short essay telling exactly what they thought of "Mackintosh's Toffee."

The prizes were awarded for merit in composition, writing and general

neatness, and the age of the competitor was taken into consideration. Many

prizes were offered equally to boys and girls, the chief prizes being a

scholarship to the value of £30 a year for three years one to the most

successful boy, and another to the most successful girl competitor.

The response was very great ; over

ten thousand boys and girls entered the competition, and naturally were

lavish in their praise of 'Mackintosh's.' The scholarships were won by a

boy in Scotland and a girl in the North of England, and it is gratifying

to know that in both cases proved a great help to them, enabling them to

continue their education for three years longer than would otherwise have

been possible. Both of them kept in touch with the firm for many years,

and the last time they were heard of the boy had secured his B.Sc., and

was making great progress in the teaching profession, whilst the girl, who

went on to college, has become Secretary to a Cabinet Minister. But every

child who sent in an essay and was not successful in gaining a prize (and

99 per cent. were in this class) received a rricely decorated certificate,

on which the child's name appeared in all the grandeur of gold lettering.

In one family this had a rather

serious comedy result, the mother receiving a certificate for each of her

five children, who had all entered the competition. The idea was sound,

nevertheless, and this general recognition of juvenile efforts did harm to

none. The children felt that they had received some little reward for

their trouble, and hundreds of these certificates were framed and proudly

hung in the children's bedrooms. Many still hang there, though the

recipients have long since left the land of make-believe for that of stern

reality.

Another method of advertisement adopted by Mr.

Mackintosh which was of considerable value to young people, was the

"School Shop." The idea was first suggested to him in the year 1914 by an

educationalist of considerable experience. A definite scheme was evolved,

in which some ten or twelve other manufacturing and advertising firms

co-operated, the aim being to link up advertisement with a practical

business training in the day-schools. The suggestions were laid before

schoolmasters throughout the country, who received the scheme favourably.

So helpful did it prove, that in a brief period it was adopted in several

thousands of schools.

The "School Shop" consists of dummy packages of

well-known goods manufactured by the firms participating in the scheme. In

this way a complete grocer's store is equipped and sent to the school.

There is paper money, invoices, order-books, and in many outfits a real

cash -till is included. This new method of teaching aroused the interest

of the scholars, and they were soon buying and selling, making out

invoices, taking off discounts and percentages, and irksome arithmetical

tasks were transformed into pretty play.

The "School Shop" outfit was found

useful in many ways. Articles such as tins, bottles, &c., were used for

drawing or painting lessons, or scholars would be required to find the

cubic capacity of some unusually shaped package. The scheme was both

ingenious and instructive, for it established a real school-shop, and

enabled the teachers to give a technical education in business methods to

future tradesmen. The educational authorities expressed their hearty

approval, and thanked the originators for the outfit which was supplied to

the schools free of cost. The scheme is still being worked in a large

number of schools throughout the United Kingdom.

Mr. Mackintosh believed that if he

could get the public to sample his goods, they would not only become

regular customers but self-appointed agents. Special caravans toured the

country from village to village and from town to town, giving away free

samples or selling small trial quantities. These vans were not limited to

England, but, twenty years ago, might have been seen on the roads of

Belgium, France, and many other countries and colonies.

Tents were also erected at

sea-side resorts for a similar purpose, and free cinema exhibitions were

given. This was quite a new departure, for at that period the

cinematograph was still something of a novelty to the general public.

Another method to achieve the same

end was to arrange with a shopkeeper in a good position to set aside a

certain Saturday as "Toffee Saturday." The arrangement was largely

advertised locally, well in advance of the day, and in consequence large

crowds of people visited the shop to receive a free sample of '

Mackintosh's Toffee.' Free coupons were distributed at the schools in the

town on the previous Friday, and a happy crowd of youngsters jostled one

another to obtain their share of the good things that were within the

reach of all. Nor were the children at home the only ones to benefit in

this way, for there is scarcely a country on the Continent which was not

visited by the Mackintosh "missionaries," and French and Dutch children

shared in the good things from Halifax.

A special line of goods

manufactured at this period, called 'The King of all Toffees,' gained for

Mr. Mackintosh the title of 'Toffee King.' He never adopted it, but it was

exploited by his American agents, as can be easily imagined, when he

visited the United States for business purposes.

His readiness in utilising any

form of popularity for his own immediate purposes was shown by his

introduction of such lines as 'Tit-Bits Toffee ' and 'Answers Toffee,'

just at the time when these periodicals were leaping into public favour.

He promptly manufactured packets of toffee, on each of which was printed

an exact miniature reproduction of the cover of 'Tit-Bits' or 'Answers,'

&c. The permission of the publishers was readily obtained, for the

advertisement was mutually beneficial.

Certain cryptic signs that are

found alongside every main railway line in the British Isles have

mystified many travellers. Mr. Mackintosh called them 'Symbol Signs.' The

letters 'M's. T. de L.' appear without any explanation on an upright

pillar in the middle of some corn-field or by the side of a wood. Ten of

these small symbol signs follow one another, then a large sign is seen

bearing the names in full, and giving the solution to any passenger whose

interest has been aroused.

These advertisements had their

amusing side. The cattle in the fields, on hot summer days, found them

useful as rubbing posts ; the farmers dressed them up during seed-time to

act as scarecrows; and at the beginning of the war, over anxious patriots,

mostly Boy Scouts, mistook them for German Secret Service signs, placed

there for the guidance of airships, and promptly reported the matter to

the police. These signs have no doubt helped to wile away many a weary

hour for travellers, making them think and talk about them and what more

can any advertiser hope to achieve?

Of the other numerous and varied

methods of advertisement adopted by Mr. Mackintosh we can mention but one

more, which was both new and original, and aroused widespread interest,

adding also its quota to 'the gaiety of nations.'

During the Premiership of the late

Right Hon. Sir H. Campbell-Bannerman, when Parliament reassembled after

the recess in February 1905, every member of the House of Commons

'received by post a presentation tin of ' Mackintosh's Toffee.' Six

hundred and seventy tins were sent to the I-louse, one for each member,

accompanied by a carefully-worded letter from Mr. Mackintosh, in which it

was suggested that honourable members in the discharge of their duties

would frequently be entertained at private houses, and that they might

like to make some little return for the hospitality given to them. What

could be better than to send the hostess a tin of 'Mackintosh's Toffee'?

Members were politely informed that they might open an account with the

firm. They need only send a card, when a tin would be forwarded to their

recent hostess with the compliments of the honourable member. Many members

took advantage of the suggestion, and several of them have kept up the

practice to the present time.

The receipt of these parcels

created considerable amusement amongst the members of the House, and

everyone was talking toffee. The primary object was thus achieved, and a

great volume of free advertisement secured for the firm. In debate members

chaffed one another about their gifts from Halifax, and it is probable

that nothing hitherto attempted had brought 'Mackintosh's Toffee' so

quickly and so easily before the public.

There was scarcely a paper in the

country that did not contain some reference to the incident. We subjoin a

few press notices for the reader's amusement.

Punch, Feb. 22nd, 1905.

The present of a tin of toffee to

every Member of Parliament on the Opening Day, although the only one

mentioned in the papers, was by no means the only one which helped to

lighten and remunerate the task of being a legis- lator. In addition,

every member was presented by 'Messrs. Toffy' with a mackintosh against

the inclement and stormy weather which the session is certain to see."

Mr. Punch's play upon words brings

to mind the following amusing incidents. A little girl, three years old,

went out with her nurse, who bought her some toffee. On returning home the

mother asked, 'And what kind of sweets has nurse bought you?' To which the

child replied, 'They are water-proof sweets, mamma.' 'Waterproof sweets?

'queried the mystified mother. The nurse explained that they were

'Mackintosh's,' and the child remembered the meaning but not the name.

Another child of like tender age

setting out for a walk with her father was sent back for her mackintosh,

and calling out to her mother as she entered the house, she said, 'Father

says you have to put my 'toffee ' on 'cos it's raining.'

Archbishop Mackintosh, of Glasgow,

was a great raconteur, and like his namesake of this biography, enjoyed a

tale against himself. He used to assert that when he was Canon Mackintosh

he owed his popularity in his parish to a happy chance. There happened to

be a favourite toffee of the same name, and the loyal youngsters of St.

Margot's munched it with approval. 'It's rale gude,' they said, 'Our Canon

mak's it himsel.'

But to resume the Press Comments:

London Daily Chronicle, Feb. 17th,

1905.

"The Everton Division of Liverpool, where there is a

by-election, is the home of a great manufacture. Everton Toffee is famous

throughout the Empire. It is the fixed belief of the electors in that

constituency that no such toffee is to be had anywhere else in the wide

world.

"When a tin of toffee was 'delivered to every member of

the House of Commons through the post a few days ago, it was at first

surmised that this had something to do with the coming contest. This

election, it was said, was to be fought on toffee, and there were serious

thoughts of asking the Speaker whether the wholesale treating of the House

of Commons amounted to 'corruption within the meaning of the Act.'

"But it turned out that the toffee did not come from

Everton. It came from a manufacturer as a plea for ' Dissolution.' '

Dissolve he wrote in a neat leaflet, 'dissolve the toffee in the mouth

before speaking, and the most taciturn M.P. will become famous for sweet

discourse.' Hence the anticipated length of the debate on the Address."

Western Morning News, Feb. 1905.

Members are enjoying the sweets of office in a

special degree. A presentation tin of toffee has come to every legislator,

and members have been seen chewing it with the zest of school,- boys. The

toffee may induce (or compel) Ministers to stick in power for some time to

come. With such rewards at hand it is not likely that they will be

dissatisfied with their lot. The dearth of speakers at certain times

during the fiscal debate is believed to be explained by the said toffee.

As a silencer it has had no rival in fact, it

would be vulgarly described as stick- jaw.' Better than the closure, and

more effective was it, for no division was necessary or possible. Members

were held speechless, glued in stony, silence, held in bonds not sordid

but sticky, which no 'Little Englander' could break asunder. Stouter than

fiscal ties, more firm than the golden threads of patriotism, was the

toffee that muzzled certain members of His Majesty's 'Faithful Commons.'

But it is a libel to say that the Cabinet Council was held to consider the

quality of the sweetmeat. That was never in doubt."

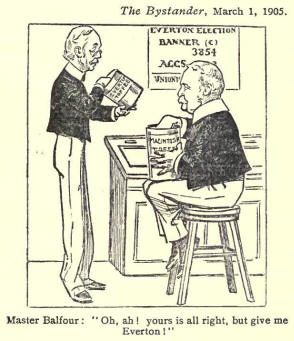

We reproduce by the courtesy of the Editor the

cartoon which appeared in the 'Bystander.' It refers to the by-election

held in Everton; the Parliamentary leaders, represented as school-boys,

are the Right Hon. Sir H. Campbell- Bannerman, who is offering a tin of

'Mackintosh's Toffee,' and the Right Hon. A. J. Balfour, who acknowledges

its excellent quality, but expresses his desire to obtain the Everton

brand.

A shoal of interesting letters were received from honourable members of

the House. Here are two examples. The first one was from a then junior

bachelor member from the Conservative side of the House, who has since

risen to a very high position in Parliamentary life :-

House of Commons,

16/11/1905.

Gentlemen,

I have received your little barrel of Old Fashioned

Treacle Toffee.

I could have

wished you had sent it to my private residence, because it is so large

that I have a difficulty in carrying it about the House.

If I put it in my tail coat pocket it spoils the set

of my frock coat, and if called to order suddenly it is difficult to sit

on gracefully.

I regret I

have not a "beautiful family," but you may rest assured it will be enjoyed

by a number of nephews and nieces who without being considered plain are

certainly not beautiful.

I

will keep your letter and send you an order for a few tins shortly. I know

the excellence of your wares of old.

Yours very cordially.

The second was from a Liberal member of the House,

and a very important personage in the publishing world, who has since been

raised to the Peerage and has held Government posts many times:

27th February, 1905.

Dear Sir,

Your very welcome gift arrived when I was out of town,

hence my delay in replying to your letter.

I do not at all regard it as a nuisance to have a

sample of toffee forwarded to me either at the I-louse of Commons or at

any other address, and in this connection I draw your attention to the

address above.

Personally I

have not taken advantage of your gift, but in a large family circle it has

been very warmly welcomed, and I am deputed by a deputation of juvenile

members of my family to inform you that your toffee is extremely good and

that no consideration of false modesty should be allowed to interfere with

your generosity in this direction in the future.

With many thanks.

Yours sincerely.

But, the forgoing examples of Mr. Mackintosh's

adventures in advertising were mere incidents in his career as a great

advertiser. His chief instrument of publicity was the press, and he made

ample use of all the national and provincial newspapers, as well as every

well-known magazine and periodical; for a generation his announcements

have reached the public through these channels.

|