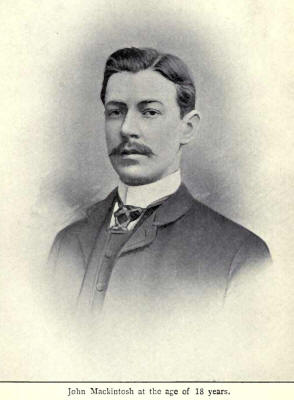

|

"Seest

thou a man diligent in his business? he shall stand before kings."—Solomon

(Prov. XXII., 29).

A sack of sugar, a tub of

butter and a few pastries ; these were the capital with which in the year

1890, John Mackintosh began the litde business which grew under his hand

to worldwide dimensions.

The pastry-cook's

shop in King Cross Lane was opened a few days after his marriage, and from

the first his young wife proved to be a true helpmate for him. All their

small joint savings were put into this venture. Even the luxury of a short

honeymoon, which they had cherished, had to be postponed, and the few days

between their wedding and the opening of the

business were spent in purchasing a few extra items of stock with the

remainder of their available cash.

Mr.

Mackintosh's business life may be divided into three periods there were

the opening five years, during which success was secured at once and quick

progress made. Then followed the period of fifteen years when he had to

work hard with practically no profits, a time when several of his

employees were receiving higher remuneration than he was making for

himself. This was the period in which the business was firmly established

on a sound basis. Afterwards came the last period of about ten years, when

real permanent success and affluence were secured. Unfortunately, he was

not permitted to enjoy for long the sweets of prosperity, for he worked to

the last day of his life.

With characteristic business thoroughness, Mr.

Mackintosh kept a careful and extensive diary recording his vast business

experience. These records are full of practical information and

suggestions of real value to business men.

The romantic story of the business told by its

founder :- "The rise and progress of any

business of repute," wrote Mr. Mackintosh, "is of great interest to many

people, and it is because we know this that we have decided to tell to our

millions of customers and others the history of 'Mackintosh's Toffee.' The

founder of the business, whose name it bears, opened his first retail shop

in Halifax, Yorkshire, thirty years ago. From the opening day this shop

attracted customers, the aim of the owner being to offer only articles

extra specially good in an establishment spotlessly clean.

"It was a pastry-cook's business, and people came

from far and near to buy the specialitie offered

for sale. After the first months had gone by the proprietor was casting

about for some new attractions to help to increase the takings of the

shop. In those days half the money taken in an establishment of that kind

was taken on Saturdays; therefore the half holiday was the

'Gala Day.' The assistants were there in full numbers, and Friday

was a hard day in the bakehouse preparing for the great sales day. The

window was packed with meat pies, fruit pies, Madeira

cakes, Eccles cakes, sponge loaves, and a thousand and one other good

things. What else could be put in that crowded window? An idea came to the

proprietor, 'Why not have just one line in

sweets, making it a special

line?

But what? Turkish Delight? Chocolate? Yorkshire Mint

Rock? &c. All were considered, all could be turned to good account, but

none of them appealed to the person most interested.

"Another idea suggested

itself! In those days there was very little in the way of toffee as we

know it to-day. English toffee was mostly hard and brittle, a pure enough

article but, lacking something; at least so thought the originator of

'Mackintosh's Toffee.' It had been noticed that caramels were being

imported into England from America. These were very soft to the teeth.

Then came the great idea! Why not blend the English butterscotch and the

American caramel? Experiments were made and an article was produced which

was named 'Mackintosh's Celebrated Toffee.'

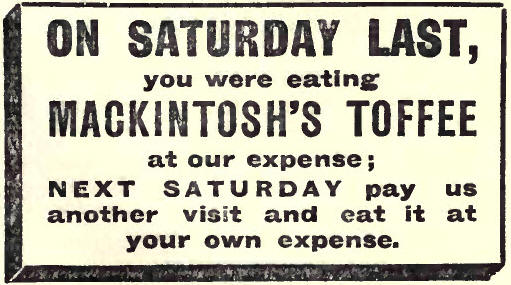

"An advertisement was put out locally in Halifax, inviting the public to

come and taste a free sample at our establishment. Hundreds came and long

before closing time we were 'Sold out!'

"On the Monday morning following, another

advertisement appeared reading like this :-

And they

did! When business opened on Saturday morning there was the largest

display of toffee (or any other special sweetmeat) ever

seen in Halifax. It began to look like a toffee shop. The pies and the

cakes, the cheese tarts and the Eccles cakes, made a brave show, but the

little mountain of deliciously inviting toffee made your mouth water.

"It could only have one end. We

kept the money separate for the toffee, and before long the takings for

the latter outstripped the receipts for all the rest of the articles sold.

"The window was painted in nice

bold letters denoting that the establishment was intended to be a

high-class pastry-cook's, but the public altered all that, they called it

'The Toffee Shop,' and people came from all parts of Halifax for the

popular commodity, but it does not come to all to carry these small

beginnings to national and then to international success."

This interesting account was, at a

later date, supplemented by Mr. Mackintosh with the following further

details:-

"I spent

the first six years, buying experience, cutting my wisdom teeth, and

putting back into the business every penny I made.

"The one great danger in a fast

growing business is that of shortage of capital for although one can

usually get all the capital one requires after a business has succeeded,

few can get it when it would seem most useful, at the beginning.

"Now a good thing soon becomes

known few people are really selfish enough to keep a good thing to

themselves; so very soon the fame of the Halifax Toffee had reached

neighbouring towns and retailers were beginning to sell it.

"That was the commencement of the

wholesale business, which rapidly spread out first to the West Riding,

then to the whole of Yorkshire, then to other parts of the North of

England, and so on, until it was being sold North, South, East and West.

"Nor did it stop there. The

Colonies quickly showed that they wanted this good old English toffee, and

other countries, too, demanded it; so that to-day from China to Peru, and

almost from Pole to Pole, there is scarcely a country that does not know

'Mackintosh's Toffee.' So from that little 'Toffee Shop' a huge factory

employing over 1,000 people has grown and given to Halifax a new fame and

a new name; for it is known to-day, the world over, as 'Toffee Town.'

"Almost every town has a shop of

some kind with a history of success in some speciality but it does not

come to all to carry these small beginnings to national and then to

international success."

This interesting account was, at a later date,

supplemented by Mr. Mackintosh with the following further details :-

"I spent the first six years,

buying experience, cutting my wisdom teeth, and putting back into the

business every penny I made.

"The one great danger in a fast growing business is

that of shortage of capital ; for although one can usually get all the

capital one requires after a business has succeeded, few can get it when

it would seem most useful, at the beginning.

"This is

not an unmixed evil, for at any rate it ensures that one will look before

one leaps. I did succeed in borrowing £50 when I commenced business, but I

got a good blowing up because I was half a day late with my interest at

the end of the first half year. I paid both principal and interest shortly

afterwards. I had more anxiety about that £50 than 'I

had from anything else in connection with the business. Later I had good

big overdrafts at the bank, but that was child's play in comparison;

because bank managers when they have once agreed to lend you a sum of

money, don't follow you about to see if you go to 'The Pictures,' or if

your wife has got a new hat. They take good care before they lend, to make

sure that you and your business are worth it. But once they have taken the

plunge it's up to you to justify their confidence, and they don't harass

you. Of course, at one time or another, most business houses have had

their principal in the 'inner room,' but one of our leading bankers

recently said, 'If there is any sweating done in that room, the sweating

is done by the bank manager!'

"I have no doubt it is a mutual affair, with the odds

against the borrower. Since then I have had the pleasure of being invited

to the aforesaid room when, I have been lending to the bank, but I always

have a 'What are you doing there, you naughty boy,' sort of feeling,

reminiscent of those days when my errand was rather different. But I must

leave a correct impression. I can honestly say that my bankers have

treated me justly. At times when I rather looked for criticism they have

surprised me with their trust in my word and their decision to back my

judgments, and to them must be given some credit for their share in the

development of my business. This is the true method of banking in my

opinion, to help to develop the businesses of the town, taking legitimate

risks along with the manufacturers or merchants.

"The second six years were taken

up in establishing business in the North of England and in the Midlands.

Our method was to work a county at a time and do it thoroughly. No town

was missed, but each was worked methodically. A map was kept in the

office, with pins something like those used in marking the advances on the

war maps, and different coloured pins were used as 'unworked' towns became

'worked' towns.

"This kind of thing went on for many years, until at last we could say

that there was not a town and scarcely a village where our goods were not

to be found. Every town is regularly visited by our representatives. We do

nothing slovenly or half-heartedly. We have a system, and no one is

allowed to upset it.

"Just going back to the beginning again, I would

recommend any person in business not to try to do too much in one day. I

remember the time when I worked hard all day at the factory and then

started on my books at night, thereby half killing myself. When I got some

one to do the books I saw what a fool I had been, for the relief was

great, and part of the time saved I was able to put into the development

of new schemes, and thus get the business further ahead with less

expenditure of energy. It is the direction of energy that counts in

business. If anyone in a business should have time to spare it is the

principal. If his every moment is occupied there is no time to think, plan

and scheme. Most businesses are crippled because the chief is occupied

from morning to night with all sorts of things that are of minor

importance. Unless they are of the greatest consequence strike against

your own system and make time for thinking."

The first supply of the toffee

that was afterwards to acquire a world-wide fame was boiled by Mrs.

Mackintosh in a brass pan over the kitchen fire. In those days it took an

hour to boil and cool ten pounds of toffee; to-day, the steam pans, each

holding several hundred-weights, are turning out nearly ten tons an hour,

and much of the machinery in use was invented by Mr. Mackintosh.

Six months after the little

business had been established in King Cross Lane, Mr. Mackintosh came to

the momentous decision to leave his secure position in the mill and devote

all his energies to the success of the new venture.

Highly coloured and highly

flavoured sweets were then popular, and these, together with chocolates,

had the confectionery trade practically to themselves. Mr. Mackintosh's

venture was regarded as risky, but from the first he realised the value of

such a homely commodity as toffee as a commercial article, and from being

a trivial article of trade he raised it to its present position as the

national sweetmeat.

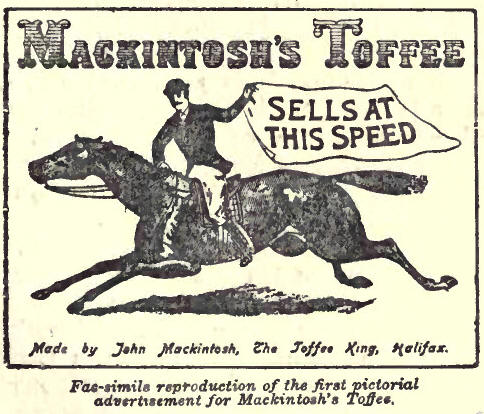

He knew nothing of such articles as glucose, vanillian

crystals, &c., nor even of thermometers there were just sugar and butter,

with a pan in which to boil the mixture. Good quality commonsense, fair

dealing and advertising did the rest. There is a Yorkshire couplet—

"Early to bed, early to rise,

Never get drunk and advertise."

It is doubtful whether Mr. Mackintosh adopted the first

suggestion, for he had to work both early and late. He certainly never got

drunk; but from the very commencement of his business he advertised.

Trade increased so rapidly that

the shop became too small, and a stall was opened in the market, a smart

young man being put in charge. The toffee was still boiled at home, poured

into trays, and packed in a tin travelling trunk. It was carried to market

in a hand-cart, and was broken up with a hammer on arrival. Not till years

later was it cut up by machinery into small pieces and wrapped and packed

in the dainty, form now familiar to us. The hand-cart was at Length

superseded by a horse and cart. The horse was bought by Mr. Mackintosh for

£11 and was named "Tommy." Some years afterwards "Tommy" was sold for

37/6. On hearing of this transaction, Mrs. Mackintosh remarked, "And I

have just paid 37/- for a wooden horse for the children."

Soon the retail shop gave place to

a small manufacturing business, and its first home was in a warehouse in

Bond Street, Halifax. This was in 1894. The following year the business

was removed to somewhat larger premises in Hope Street—an appropriate

name—the top floor of which was rented. Trade continued to increase, and

in 1899 the factory in Queen's Road was built and equipped with the most

modern machinery. The following year the business was turned into a

private company, and other factories were acquired in the town.

When the business expanded to

national dimensions the Company's financial resources were drained to the

last farthing, and the chief difficulty was not to get trade, but to find

the money requisite to run the works. Though the business was highly

successful, the want of capital on several occasions nearly brought it to

an end. Money was required for the purpose of extension both at home and

abroad. The pinch was felt most severely at the close of the South African

War, when the Government put a tax on sugar. This made the confectionery

trade a lean thing just at the time when fresh capital was needed in every

direction.

But

difficulties only proved the man. A directors' meeting was held in Mr.

Mackintosh's home, when he was suffering from a severe attack of gout. The

bank was pulling him up when the business was making great headway. No

possible means of getting over the difficulty presented themselves. The

outlook was black, and even to continue to run the works for another week

appeared impossible. But in face of impending disaster his faith and

courage did not falter, and he declared that he 'would never be beaten,

and if necessary he would begin again at the bottom.'

Mr. Mackintosh possessed a

wonderful power of inspiring others with his own optimism. Even the least

hopeful began to believe in the possibility of success. At length the

clouds rolled away; but for many years not a single penny was paid in

dividends.

Some

people do not care to be reminded of their early days, when with little

experience, less capital and no encouragement, they fought their way to

the top. But Mr. Mackintosh was always ready to talk about his early

struggles, and though he could laugh and jest over experiences that were

grim enough at the time, he was never ashamed of them. He had proved that

he was acting on sound lines, and there is much satisfaction in finding

that the hopes and aims of past days have been realised.

It was the remembrance of his own

trials that caused him to lend a sympathetic ear, and often helpful hand,

to other business men in difficulties. Of many such kindly deeds there is

no record, for 'He did good by stealth, and blushed to find it fame,' and

he endeavoured to make those he thus lifted up feel that they were under

no obligation to him. So long as the man was obviously trying to do his

best, Mr. Mackintosh would trust him absolutely, and whether things went

well or ill would never chide or complain; nor did he expect to share in

the success which he helped to achieve.

The strain of a great business did

not make him slack in his work for the Church and Sunday School. He would

often remain at his office until 7 or 8 o'clock in the evening, then go

straight to Queen's Road Sunday School to attend a Church meeting, either

of a business or religious character, returning at its close to his desk

until midnight. Nor did he regard this work as being of small value to

himself, for he frequently declared that much of his ability to conduct

his own business and to deal tactfully with other men came from the

experience gained when in office in the Sunday School.

Mr. Mackintosh's family naturally

displayed a keen interest in the business. When his eldest boy was only a

little fellow, he used to include in his prayers the following quaint

petition: "Oh Lord take care of the works, and never let them be 'blowed'

up, nor 'blowed' down. And they were not; but he forgot to mention fire.

On November 2nd, 1911, the works at Queen's Road were burned to the

ground. This disaster coming just when the worst of Mr. Mackintosh's

difficulties were surmounted, was a heavy blow to him. His house was only

a short distance from the factory, and in the dead of night he was

awakened by a man informing him that a little puff of smoke was issuing

from under the warehouse door. This was evidently his kindly way of

breaking the news, for he had scarcely uttered the words when the roof of

the factory fell with a crash, and the glare of the flames illuminated the

country-side for miles around.

Mr. Mackintosh was quickly on the spot, and after doing

all that was humanly possible, he saw that the works were doomed. His

mother's house was opposite the burning building, and this greathearted

man took his wife across, and together with the mother they knelt in

prayer on the floor of the little parlour. There, with the room lighted up

by the flames from the ruins across the road, they commended themselves

and all their affairs to their Heavenly Father's keeping, and "cast their

burden on the Lord."

This was the last serious check that Mr. Mackintosh had

to sustain, and he acted promptly, with his accustomed energy and

foresight. The business was at once transferred, in part, to premises

adjoining Halifax Station. Gradually the entire business was resumed in

the newly acquired buildings, and then rapidly extended, until at length

the present large group of factories was occupied. These splendidly

equipped works are ten times greater in capacity than the one destroyed by

fire in Queen's Road. That factory has now been rebuilt, and is the home

of the chocolate branch of the business. It is an interesting comparison

to note here that for many years the great firm of 'John Mackintosh Ltd.'

has produced toffee in such huge quantities, that it has had the heaviest

railway carriage account of any firm in Halifax and district.

When the first company of John

Mackintosh Limited was floated in the year 1899 the capital was £15,009,

Mr. Mackintosh receiving as the purchase price a large proportion of the

Ordinary Shares. The issue, small as it was, proved to be greater than the

faith of the promoter, for it was under-subscribed by the sum of £3,000.

It was essential that the entire amount should be raised in order to

complete the building of the new factory. Mr. Mackintosh requested his

solicitor to accompany him to the bank, where they interviewed the

manager, and asked for a loan of £3,000. The manager was indignant, and

resented even being asked to make such an advance for the purpose of

manufacturing toffee. "Why," said he, astonished at the audacity of the

applicant, "if you made all the toffee that the United Kingdom could

consume, you could never employ £15,000 capital. I call it fool-hardy! "

The bank manager was obdurate for a time, and absolutely declined to find

the money. But after three other interviews he relented though, before the

money could be obtained, Mr. Mackintosh had to deposit as security every

share he had received in payment for the business.

The local printer who printed the

prospectuses of the company relates that, when Mr. Mackintosh went to pay

the account he was given half-a-dozen spare copies which were left over.

Putting them into an envelope, Mr. Mackintosh said, "We will keep these;

they will come in useful when we are floating it for £100,000." Since

then, in the present year, 1921, the new company of John Mackintosh &

Sons, Limited, has been formed, with a capital of £750,000!

Such is the romance of business.

|