|

"I

am a moderate man and can 'live and let live, looking for the best and not

the worst in everyone."—J.M.

Halifax has been

singularly happy in being the mother of men with a genius for business,

who became the architects of their own fortunes, and then lavished their

wealth in providing charitable institutions for their native town. Sir

Francis Crossley, the head of the great carpet industry which made Halifax

famous in the last century, with his brothers John and Joseph, were a

triumvirate of whom any community would be proud, and their wise

benefactions have blessed thousands of the citizens of Halifax.

There was also Colonel Edward Akroyd, whose father, like the father of

John Mackintosh, was a member of Salem.

John Mackintosh was a man of like type. His gifts to

local charitable institutions were large, and ever increasing in

magnitude, and had his life been prolonged these would have continued. But

doubtless the trying experiences of his early business life sapped his

health, and to the fearful strain of this period we must attribute his

comparatively early death. Ile packed so much into the fifty-two years

alotted him, that it might be said of him in the

words of Eliphas the Temanite, that, He came to

his grave in a full age, like as a shock of corn cometh in his season." A

man's age is not to be fixed by the calendar, for empty

years do not count ;-

"A life of nothing's nothing

worth, From that first nothing ere the birth To that last nothing under

earth."

There is little doubt that had

Mr. Mackintosh aspired to Parliamentary honours he could have risen to a

high position in political life. Not that he possessed any showy

qualities, but because of his clear, wide vision combined with practical

efficiency. No one would more heartily subscribe to Dr. Clifford's

declaration that "Cleverness is the bane of modern life." His moderation

would not permit him to follow the 'Nestor of Noncomformity' in all

things, but he was always suspicious of mere cleverness. Nor was he in any

sense an opportunist, but referred the solution of any problem to great

central principles. However, his time was so fully occupied with his

business and the affairs of his church, that a close devotion to politics

was out of the question.

It is no secret that the

Mayoralty of the town could have been his had his health permitted. In the

year 1913, after repeated representations had been made to him by his

fellow-townsmen, urging him to enter civic life, he became a member of the

Halifax Town Council, being elected for the ward wherein he had lived and

worked all his life. One paragraph in his election address, stands out as

typical of the man and his direct homeliness:- "I think I know something

of the worries and anxieties of the various classes which make up the

residents of the ward, and if I am fortunate in being elected your

representative, I shall do my utmost to lessen these worries. Whilst I

have my political and religious opinions, I am a moderate man, and can

live and let live,' looking for the best and not the worst, in everyone."

Mr. Mackintosh's knowledge of the

geography of the British Isles was almost perfect, his business and

philanthropic interests having taken him to all parts of the United

Kingdom. As we know he frequently visited America and most Continental

countries, and on these tours he had been a keen observer of the life,

customs, and methods of government of the various nations with whom he

came into contact. In consequence his outlook was wider and his attitude

more tolerant, than that of most men, and this was a good equipment for

public life.

His own account of his early

experiences on a public legislative body is vivid and interesting. At a

local gathering he remarked:

When I was sent to the Council I

felt like a boy who is going to school. I was still in 'StandardI'

learning to make pot-hooks. But I do not think I blotted my copy-book very

much, chiefly because I have been careful not to do too much. At any rate

I am beginning to feel at home, and when one feels at home one wants one's

own way, and in committees I have often surprised myself by joining in the

arguments. However, I think I am getting on, and may find myself in

'Standard II.' some day."

This is a peep behind the blind

that gives us a glimpse of the man's true personality. He was ever

perfectly frank with those for whom he was striving, and was not content

to lay results before them without explaining how and why those results

had been achieved, and he never hesitated to tell them of the personal

difficulties he encountered.

He soon won the respect of his

fellow councillors and the absolute confidence of his constituency. He was

neither strongly Liberal nor Conservative : mere party shibboleths had no

attraction for him. The People, spelt with a capital P, and not party, for

which in his judgment Roman lettering was sufficient I How true a test is

this of the breadth of a men's mind! Yet he could not be classed as an

"Independent," which is often the label of a mere crank. He was the

people's representative, and he would vote for anything brought in by any

party which he believed was for the good of the community as a whole.

When he became a magistrate for

the Borough of Halifax he arrived at a position which he esteemed very

highly. The dominant thought in his mind was how to temper justice with

mercy, in the cases of those poor unfortunates who, did we but know all

were more sinned against than sinning." Incidents of his sympathy and

tenderness of heart when on the bench were numerous and striking. He was

not given to the utterance of witticisms after the manner of some, but he

earnestly strove to hold the balance even and to "make the punishment fit

the crime." In this he feared lest through an excess of sentimental feel-

ing for the weak, he might be excessively severe towards the strong and

guilty. "We have wife-beaters " he wrote " I like to give them "gypI'" But

the child-offender and the aged and decrepit found in him a friend.

The quality of mercy is not

strain'd,

It droppeth as the gentle rain

from heaven Upon the place beneath: it is twice bless'd It blesseth him

that gives and him that takes."

John Mackintosh put these

immortal lines of Shakespeare into practice in such a way as to take the

guilty hope and the innocent fear not.

On one occasion an old-age pensioner came before him

charged with committing a technical error in not declaring a few extra

coppers of his income. He was fined two guineas, but on leaving the Court

he was met by Mr. Mackintosh, who presented him with the amount of his

fine, the solicitor following this good example by fore- going his costs.

At another time some boys were brought before the

court charged with playing in the streets. Here was exactly the type of

offender whom Mr. Mackintosh could not punish, nor permit others to punish

if he could prevent it. He persuaded the magistrates to dismiss the case,

"For," said he, "there is

no other place for them to play in." A sensible attitude to adopt.

A great number of people of all ages came to him for

advice on every conceivable matter, from finance to domestic trouble. One

woman came to see him because her neighbour had given her a black-eye,

another as to whether she might be permitted to give a similar decoration

to her neighbour, because "She went and dropped my baby o' purpose." When

such people were questioned as to why they went and told their troubles to

Mr. Mackintosh, they replied, "Well, he knows

all about us, and he has a kind heart and will help anybody."

In the social life of the town he was known as an

ardent supporter of the temperance cause, but he was no more narrow and

bigoted in this cause than in any other.

He delighted in the work of the Band of Hope. The

movement in Halifax was at one time badly in need of a real leader who

could and would lead. Mr. Mackintosh was the ideal man, but it seemed to

the general secretary that it was too much to

ask from a man on whose shoulders rested already such tremendous

responsibility. However, he was soon relieved from his anxiety, for in

answer to his invitation, Mr. Mackintosh replied with his usual directness

;-

"I would rather be

President of the Band of Hope than Mayor of Halifax."

"I have friends," said he,

in every walk of life, and amongst them many who are not total abstainers.

There are brewers and hotel proprietors I very much respect. I am bound to

because of their kindness of heart. But these friendships do not prevent

me doing all I can for the cause of temperance. I never believe, however,

that you can make a man a teetotaller by knocking a glass of beer out of

his hands. If one tried this one would probably get a knock back and

deserve it."

His great love for children made him favour the Band

of Hope in preference to all other temperance movements. Because this

organisation appealed to children it appealed to him. He believed in

educating children in temperance principles as well as in other matters

vital to their well-being; but he had little sympathy with what he used to

call "street corner oratory." He did not therefore give much time to

appealing to adults on the temperance question, believing that when a man

had reached years of discretion he had a right to his own opinions.

When the question of nationalisation of drink arose

he took a determined stand against the majority of temperance workers,

telling them plainly that they ought to have accepted the proposals. In

this his practical common sense was apparent. Realising that half a cake

is better than no cake at all, he saw that, with the traffic in the hands

of the nation, many of its evils would be done away and half the battle

won. One of his Last acts, a few days before his death,

was to make over several hundred pounds to the local branch of the Band of

Hope Union, in order that his subscription of ten guineas per year might

be theirs for all time. He also completed several other schemes which he

had long had in mind in regard to his church and his business; which,

viewed in the light of subsequent events, seems to indicate a premonition

that his work was nearly done.

Mr. Mackintosh himself was a

life-long abstainer. His mother took him when he was quite a little boy to

various temperance meetings, and the impressions made on his young mind

were never effaced. Those were the days when the Late W. E. Gladstone was

the uncrowned king of England, and to him young England looked as a "saviour

and commander to the people." At one of these meetings, after hearing of

the havoc wrought by excessive drinking, the boy turned to his mother and

asked, "Why doesn't Mr. Gladstone stop it?" Unfortunately, older people

ask like questions concerning this and other evils, and often blame

statesmen for not performing impossible tasks. But when he grew up he was

wiser, and he could not be harsh in his judgments, nor extreme in his

views on any subject. His attitude as a leader in the temperance cause was

always sane, and like Oliver Twist, he would take all that was offered and

then ask "for a little more." Had such wise counsels prevailed in the past

much more would have been accomplished.

He was one of the stalwarts of the

movement, but his judgment was unfettered by prejudice. Presiding over a

large temperance meeting in Halifax, he clearly distinguished between the

use of alcohol as a beverage and as a medicine. He had no sympathy with

the attitude of mind which led some to say that they would sooner die than

take alcohol, and he bluntly told the meeting that in the horrible

trenches in France his son's life had been saved by the administration of

brandy. This statement aroused much heated controversy, to which he showed

supreme indifference. His sanity kept him from all kinds of intemperance,

whether of thought or speech, as well as in matters of eating and

drinking. Extremists injure every cause they advocate.

A remarkable gathering was held

under the presidency of Mr. Mackintosh in connection with the Halifax Band

of Hope Union in the Central Flail. The meeting was convened for the

purpose of presenting long service diplomas to seventy-seven friends who

had been temperance workers for twenty-five years and over. The aggregate

number of years of service for the temperance cause, represented by the

recipients, was 2,698, and five of them had each a record of half a

century or more. Mr. Mackintosh, with characteristic humour, suggested

that it was a kind of "Temperance Love-feast."

FTc never took up any public work

which did not present an opportunity of doing good to his fellow-men.

Everything he did in his public life he regarded as part of his religion.

When- ever his special knowledge would be helpful to any organisation, it

was always placed unreservedly at the service of the public. To him no

meeting was too small, or too trivial, if through it some good might be

achieved.

"Nothing in life," said he, "is so

small that it can be safely neglected."

When he became a director of the

Halifax Equitable Bank and Building Society, he accepted the position

because of his gratitude for the help he had received in the past from

this and similar institutions. His first small savings of a few shillings

a week were made here. He hoped that as a director he might be able to

help others in the same way. In this capacity he did much to encourage

thrift in families with small means, and to assist them to rise to

positions of greater ease and comfort. But these represent only a small

portion of his helpful activities; for he was Vice-President of the Young

Men's Christian Association; the Business Men's Club; and the Tradesmen's

Benevolent Association and a host of others. It is a matter for wonder how

he found time to Datronise, and take some part in the business of so many

small associations, but he did it nevertheless.

He became a trustee of the

Ex-service Men's Association, and he showed a strong interest in the men

Who had fought, and who were in danger of being forgotten when the glamour

ol the fighting had passed away. Many others apparently considered that

with the cessation of hostilities their responsibility ended for the men

who had given up home and business for their country's sake, and in some

instances had lost both. As a vice-president of the Y.M.C.A. he came into

close contact with the soldiers on leave, and with those who were on duty

at home. In the dark days when he knew, as thousands of other parents in

the British Empire knew of their sons, simply that he was reported

"wounded and missing," his courage and trust in God never failed. He went

his way easing his own hurt by cheering other poor souls who suffered a

like sad anxiety. Throughout the entire period he made enquiries for the

sons of other distressed parents as well as for his own son. Many a

sorrowing wife and mother who received his kindly sympathy and assistance

in those awful times thanked God for sending John Mackintosh to bring a

ray of hope and comfort into their darkened homes. So many were the

demands made upon him for information that he had a circular letter

printed giving directions to parents of missing soldiers, and teaching

them how to make enquiries through the proper official channels.

It afforded him the deepest

satisfaction that in these trying times he was able to render generous

financial help to the various soldiers' and sailors' funds. The Prince of

Wales Relief Fund, The Prisoners of War, and the local "Comforts" funds

continually received substantial assistance from him. It was "For

England's sake," and he felt that he could not do' too much nor give too

often, nor too freely, for such a cause.

He encouraged the study of music

amongst the young people, and for many years he conducted the musical part

of the Sunday School Anniversary at "Queen's Road." There was never a more

popular leader, for "he had a way with him," and was able to get the very

best out of the children. The anniversaries in which he took this leading

part are amongst the most cherished memories of his friends, especially of

those who were children under his instruction. He also became president,

or patron, of nearly all the brass bands in Halifax, and he promoted the

formation of the Mackintosh Glee Party at his own works. They rendered

much assistance to the churches and philanthropic institutions of the

town, visiting the hospitals, especially during the period when they were

crowded with wounded soldiers. This Glee Party still keeps up its

traditions and its numbers. It is a mixed choir of about fifty voices, all

the members being associated with the various enterprises of the firm.

He was the friend of all

associations for the purpose of fostering healthy out-door games,

especially football and cricket. Right up to the end of his life he would

attend football matches, and go occasionally to see county cricket,

especially that struggle of giants when Yorkshire met Lancashire. For

local cricket he rendered inestimable service, patronising dozens of

junior clubs, and presenting the "Mackintosh Cup" for competition amongst

local amateurs.

Both in public and in private

life, he was remarkable for his love of children and his power over them.

He had a natural gift of speech to children, and his addresses were so

Simple that all understood them, and so full of the minute details dear to

the heart of a child, that all were interested and instructed.

Children without-exception loved

him with all the ardour of which their young hearts were capable. He could

make up a tale for them on the spur of the moment, and he had a store of

little tricks which were a never failing source of amusement. He never

went anywhere without a pair of folding scissors in his pocket. He would

cut out paper trains, fancy d'oyleys and a variety of other pretty things,

thus keeping his youthful audiences amused and interested for hours

together. Even in foreign countries he would gather crowds of restless

children about him, and though unable to speak a word of their language,

maintain their interest all the time they were with him. He had tricks

with matches, pennies, and handkerchiefs which earned a volume of

appreciation that would have warmed the heart of any professional

entertainer.

He was not an artist, but he had

an ever ready pencil, and many were the homely and humorous pictures he

drew for his young friends. A great favourite was one which represented a

railway station with every detail given, from the advertisement plates on

the walls to the inquisitive old woman worrying the station-master.

Another scene was the representation of the ever popular seaside, with

sands, castles, steamers, yachts, lighthouses and seagulls. Nothing

essential to the juvenile imagination was omitted from the picture. He

also did conjuring tricks, and hundreds of people, both young and old,

have been amused.

These things, though so simple in

themselves, reveal a wonderful personality and a fertile brain. He was

able to grapple with any problem, whether in his great business or in the

children's nursery. His first thought, on returning home after a busy day

when his children were young, was for the little people, even before his

evening meal and comfortable chair. The shrieks of delight with which he

was received nightly in his own family circle, testified to his

realisation of the ideals of true parenthood.

In all great decisions Mrs.

Mackintosh was first consulted, and instead of restraining his generous

impulses she urged him to do all that was in his heart. She acted as a

spur rather than a rein on his beneficence, a spur to which he never

failed to respond. No man's record who has accomplished much in the world,

is complete without reference to some woman, wife, mother, or sister, and

it is largely owing to the good woman, who so bravely and patiently bears

her loss at " Greystones " that there is so much that is worthy of

remembrance in her husband's life and work. It was her gracious influence

that enabled him to thread his way through the maze of public life with an

ever cheerful spirit, a clear vision of all that was of real value, and a

soul that was untouched by the sordid spirit of the age. His daily prayer

was that of the saintly Father of the Church:- "Give me, O Lord, a heart

that nothing earthly can drag down."

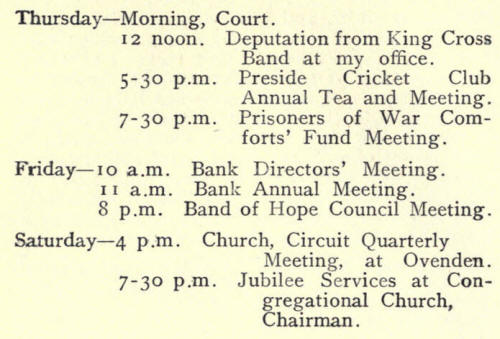

What Mr. Mackintosh's public

duties involved may be partly guessed from the following page taken from

his diary representing an ordinary week's public work, apart altogether

from his business appointments

Sunday-3 P.M. Speak at P.S.A.

6-30 p.m. Special Choir Services, Church.

Monday—Morning, Court.

4 p.m.

Tramways Committee.

6-30 p.m. Baptist Church, Annual Band of Hope

Meeting, Chairman.

Tuesday—Morning, Court.

3 p.m.

Opening Missionary Bazaar, Sheepbridge.

7-30 p.m. Chairman. Commercial

Travellers' Temperance Association Meeting.

Wednesday—11 a.m. Waterworks

Committee.

3 p.m. Deputation from Y.M.C.A. to see me at office.

Evening—Council Meeting.

|