|

1863-68

IN tracing the last

footsteps of my lamented brother at Peking and Nieu-chwang, I have been

happily furnished with such ample materials from the hands of loving

brethren of different Christian communions, that it will scarcely be

necessary for me to do aught more than simply to quote their tender and

graphic words. Some of these communications have come so spontaneously,

and from quarters to me so unexpected, that it has seemed but as the

breathing fragrance of precious ointment, which must flow forth, and

which cannot be hid, when the alabaster box is broken. To this part of

our narrative the following vivid and interesting notices, from the pen

of S. Wells Williams, LL.D., Secretary of the United States Legation at

Peking, will form a peculiarly appropriate introduction—all the more so

that they are in part retrospective, touching the missionary’s career at

various points, where the paths of the two friends crossed one another

during the course of twenty years:—

“When I recall,” says this distinguished scholar and missionary, “the

voice and form of Mr. Burns, they revive my earliest notions of one of

the old Hebrew prophets, of a man whose high vocation had somewhat

separated him from common communion with those around him; this idea

impressed itself so much upon my mind when I first met him in Hong-Kong,

in Sept. 1848, that it always invested his character and name, and does

so even more now that he has gone. Our intercourse was of the most

cordial nature; but being a printer, and having no work with him, I was

not so much thrown into his company as he was with Dr. Hobson at Canton,

Mr. Doty at Amoy, and others who had chapels where he could preach. I

have therefore not so many recollections of Mr. Burns as might be

inferred from an acquaintance of twenty years, and fyave not preserved a

single line of his writing.

“His determination and singleness of purpose in the mission work were

illustrated in his account of the way he began the study of the language

on his voyage to China. The only book which he could find in London to

aid him in this study was my English and Chinese Vocabulary; with this

he procured a volume of Matthew’s Gospel, and perhaps a tract or two. He

then examined the first verses of the 2d chapter, learned the figures so

as to distinguish the verses, and taking the first characters, hunted

through the Vocabulary till he found them as the Chinese equivalents of

the English words, reconstructing the sentences, as he found one word

after the other, until he had found out the sound, meaning, and radical

of each character. Then he wrote them over and over, until he had

acquired them thoroughly. This tedious way of learning the characters

was continued until he arrived in Hong-Kong; but no one, unless

acquainted with the Chinese language, can fully appreciate the tedium of

acquiring its characters otherwise than by beginning with the radicals.

I think he went over nearly the whole Gospel in this way before the end

of the voyage, and then sat down to the study with a preparation and

zest that few have brought to the task. It was a pleasant gratification

to me to learn that the time spent on that small vocabulary had helped

Mr. Burns in his labours, for I remembered how helpless I felt on my

voyage out fifteen years before, when I had no possible means of

learning a single character, and reached the country quite ignorant of

the people and their language.

“I went to Canton, and saw no more of Mr. Burns until he came to that

city to live in 1850. Before that date I heard of his having been robbed

of all his baggage while living on the mainland, opposite Hong-Kong,

whither he had gone to see what could be done in effecting a settlement

among the people. The thieves broke up his quarters, and while he was

present helped themselves to clothes, books, and money as they pleased,

leaving him just enough garments for protection, and means to get back

to Hong-Kong. One fellow had his hone, and being puzzled to know its

use, brought it to Mr. Burns to learn what it was fit for, and was

patiently taught the mode of sharpening a razor or knife on it. These

ruffians did not belong to the villagers, but the latter made no attempt

to defend or protect the foreigner. But, no doubt, this beginning had

its salutary effect upon them.”

From another informant I am enabled to add one or two further touches'

to this characteristic and romantic incident. He had, it would appear,

with some hesitation, and without any clear indication of the Master’s

will, proceeded westward beyond the range of his first labours, into a

part of the country where the people were notoriously less accessible

and friendly; and being afraid that he had run, without being sent, into

the midst of unknown difficulties and dangers, he had lain long awake in

anxious and pensive questioning. While still thus musing he became

suddenly aware of the presence in the chamber of two muffled figures,

who, approaching with stealthy steps and blackened faces to his bedside,

stood over him with naked swords held to his breast. “Do no violence, my

friends,” he said calmly, “and you shall have all I have;” and then

followed the characteristic scene described by Dr. Williams. When the

landlord of the house came in next morning to condole with his guest on

his loss, “ Poor fellows!” said he, “let us pray for them.” The robbers

took with them literally all he had, save only the contents of a loose

bag, which lay in a corner of the room, and which, seeming to contain

nothing but useless papers, had fortunately been neglected by them.

Beneath the papers, howevpr, there were some shreds of under garment, of

which the missionary contrived to make for himself an outlandish

costume, in which he found his way back to the sea-coast, and thence to

Hong-kong; waiting under cover in the boat until the return of a

messenger supplied him with the means of appearing on shore in a more

appropriate garb.

“At this time,” continues Dr. Williams, “the controversy among

Protestant missionaries, in respect to the best word for God and god in

Chinese, was carried on very warmly, and our friend could not but enter

earnestly into the discussion of so vital a question. He and I took

opposite sides, and we had some discussions on the nature and value of

the arguments used in support of each, especially on the plurality of

the idea connected in the minds of the natives with the word shin, which

to him was an insuperable reason for not using it for the true God. Mr.

Burns had the true Scotch mind, and when he had made up his opinion,

nothing had much power to move it. Views that to my mind had much weight

to modify this idea of the plurality of the word shin, seemed to carry

none to his; he had settled the matter in his mind, and the question

need not therefore be revived for re-examination.

“Dr. P. Parker had religious services at his house every Sabbath

evening, and Mr. Burns often conducted them, preaching at times with

great point and solemnity. The audience consisted mostly of the

missionaries and their families; but if the one whose turn it was to

hold the service, was unable from any reason to fill his place, Mr.

Burns usually supplied the gap, for he had said that he never could

conscientiously say no to any application to preach, as long as he was

physically able. There was therefore great disparity in his public

ministrations, and sometimes he repeated himself without perhaps knowing

it; I don’t think that he preached once in my hearing from notes, and as

the week had been taken up with Chinese study and preaching, he, of

course, could only make short preparation for these Sabbath evenings.

Yet his intimate acquaintance with the Scriptures enabled him, if he was

in good health, to illustrate and enforce the text and its instruction,

so that every one could carry away a warning or an encouragement that

would benefit him.

“After a while circumstances arose that rendered it desirable in his

opinion to remove some of the meetings held at Dr. Parker’s house, and

Mr. Burns took a leading part in endeavouring—first, to prevent moving

them at all, by obviating the causes which suggested it; and when this

was found unattainable, by explaining the reasons which led to such a

decision, in a letter he wrote upon the matter. The discussion continued

for a week or two before the matter was settled, and during the days it

went on I was struck with the manner in which feeling was restrained by

a sense of duty in his mind. To most of the missionary circle, it seemed

on some accounts best to content ourselves with an expression of

opinion, and let that opinion gradually have its due weight in leading

to a change in practice on the part of those we felt were

fellow-Christians; but with Mr. Burns the witness must be borne at any

rate, and the consequences be left with God.

“He was induced ere long, by the little success the work had at Canton,

to go further north, and try to reach people who lived away from so much

contact as the Cantonese had with foreigners. He found the work more

congenial at Amoy and Swatow, where, and in their vicinity, he spent

many years, and did a great and lasting work in extending missionary

labours among their rural populations, and founding Christian

communities.

“In August, 1854, I arrived in Amoy soon after his co-labourer, Dr.

James Young, was laid aside from his work by illness. As soon as Mr.

Burns heard of a sudden access of the malady, he came in from the

country, to start immediately for home with the invalid and his

motherless children. He consulted with no one but his Master, and every

one agreed that the decision was a proper one, much as all his

associates regretted the cause and its effect—the illness of one, and

the absence of the other from his interesting meetings in Pechuia. It no

doubt saves much heart-rasping and mind-wearying thought, to be able, as

he did, to decide at once, and act on a point, even if sometimes one

acts unwisely. The next thing was to get a passage to Hong-Kong as soon

as possible, in time for the outgoing P. and O. steamer. The only vessel

available was the U.S.S. Powhatan, and the captain deemed it unadvisable

to take the party as passengers. However Mr. Burns carried the day

against the objections of the captain, whose ill-health was after all

the principal ground for at first refusing the application. The skilful

manner in which the domestic tie, of a darling daughter of the captain’s

in America, who was about the same age as Dr. Young’s child, was brought

up by our friend to induce him to carry the invalid to Hong-Kong, showed

a good deal of insight into human nature.

“It was on the way to Hong-Kong that I learned all that I then knew of

this first outpouring of the Holy Spirit [in China],1 and heard from his

lips how he had been led to go to this place by much the same influences

as Philip the evangelist was led to go towards Gaza. I had been in China

in the mission work twenty-one years, and now the blessing had really

descended in an unmistakable way; and I rejoiced with him at the native

agency and thoroughness of the work, and how God had taken the weak

things of the world to show the power of his grace. I felt more

encouraged than at anything I had before heard in China; and the

evidences of God’s approbation of the mission work here, which this

movement then showed, have ever since gladdened my heart, and

strengthened my faith in its final triumph.

“After Mr. Burns’ return to China, I saw nothing of him till he had

reached Hong-Kong, after his liberation by Governor Yeh at Canton, in

October, 1856, after they had brought him overland to that city from

Chaon-chow-foo by way of Kiaying-chow, in the eastern end of the

province. He there learned that some of the native Christians who had

been with him at Swatow before his own arrest, were in prison, and he

wished to get near to them so that he might do what he could for their

welfare. There was no vessel going to Swatow except a small native junk,

and we dissuaded Mr. Burns from embarking in such a rickety craft at so

late a period of the year, even as a matter of time; for by a little

delay he would no doubt find a safer vessel, which would land him there

quicker. But nothing would move him. He had heard the voice of God, and

felt no fears as to the result of the voyage. He left that night in her,

reaching Swatow after nearly a month’s tedious coasting, which however

was, I suppose, no loss to him, for he preached to the crew, and

suffered no derangement in his plans by the delay. This example of our

friend, in regarding the people wherever he met them as his audience, is

one that cannot be too strongly urged upon all heralds of the fruits,

even then already ripe, of that previous Amoy work. There seems also to

be some confusion as to the ‘influences’ which led to visiting Pechuia:

these were the invitations of persons who had heard the gospel at Amoy,

and the gospel in heathen lands. Yet this feature of his mind had its

effect in deterring those around him from giving him advice when he

asked it, inasmuch as he followed his inward convictions sometimes when

outward arguments tended the other way. In this instance, the time of

the year, and the unsettled condition of the coast, would have weighed

with most men to seek another mode of conveyance; but whether such a

course as he took in such dilemmas—that of seeking a manifestation of

some kind to know what the will of God is—would answer for all, or

whether all are capable of hearing the inward voice, is a curious

question. I have never known another person who had as little hesitation

in following what he regarded as this inward monition and guidance. In

this instance there was no long weighing of the reasons, nor much

discussion upon their value; he had looked squarely at both sides, and

his choice had no revision.

“After a lapse of six years, during which Mr. Burns had proved his

devotion to the mission work in Fokien and Kiangsu by travelling and

preaching, he and I arrived in Amoy the same day, he from Fuh-chow in

April, 1862.

“Travel and exposure had made their marks on him, but he was still

vigorous, and was projecting new trips in the surrounding country, then

opening more than ever to the preaching of the gospel; and I was glad to

hear how the work had progressed since the day he told me the story

about Pechuia, eight years before, on board the Powhatan. I took a

review of the twenty years which had elapsed since Dr. Abeel and Bishop

Boone left Macao, in February, 1842, to begin a mission at Amoy, where

the latter buried his admirable wife, and the former laboured on in

faith and patience until others came to his help, and others to theirs,

until we now see a Christian community preparing to take its place as an

acknowledged fact in Chinese society. In laying the foundations of this

blessed superstructure, few have done more to the glory of God than

William Burns.

“The purpose for which he came to Peking in 1864, to endeavour to obtain

the same recognition of the civil rights of Protestants that the Roman

Catholics had, was not attained in the manner he wished; but his mission

was not fruitless. He made known the condition of the missions in Fokien

province to the late Sir Frederick Bruce, and gave him a juster

perception of the mode of carrying on missionary work than he had

before, and the nature of the disabilities under which the converts then

laboured. Sir Frederick declared that Mr. Burns was one of the most

fascinating men in representing a case that he had ever met, and gave

one a clear idea of whatever he undertook to describe.

“The daily routine of the life he led in Peking for three years was very

uniform. He dwelt by himself in one room, his own servant occupying the

next, and almost every day visited one or other of the mission chapels

connected with the four missions in the city. The version of the second

part of the Pilgrim's Progress is likely to be the most permanent of his

literary labours in the northern dialect; for his Peep of Day and the

version of the Psalms in tetrameters are less acceptable to native

taste. He visited frequently at the houses of his friends, who were

always cheered by his presence, and towards the last part of his stay he

gave all his strength to preaching the gospel to such audiences as were

gathered in the chapels.”

In another letter, Dr. Williams adds:—“In Peking I saw more of him than

previously, and enjoyed his visits at my house greatly; he was

particularly interested in the progress, causes, and conduct of the

slavery war in the United States, and kept up a minute acquaintance with

its events, studying the geography of the seats of war, the character of

the principal leaders and generals, and the changes of public sentiment

as the war developed more and more the detestable nature of the bondage

of the slave.”

To another valued friend and true yoke-fellow in the work of Christ, the

Rev. Joseph Edkins, M.A., of the London Missionary Society, I am

indebted for the following graphic and touching memorials, which will

form a fitting sequel to Dr. Williams’ narrative, and give to us a still

more distinct idea of the nature of his work, and of his manner of life,

during those quiet and comparatively uneventful years—the land of Beulah

of a life which had had in full measure its Hills of Difficulty, its

combats with Apollyon, and its solemn witnessings in Vanity Fair, as

well as blessed glimpses of the Celestial City from the heights of the

Delectable Hills:—

“The Rev. W. C. Burns came to Peking in 1863, and at once opened to Sir

Frederick Bruce the matter to attempt the settlement of which he had

come. He went to stay with Rev. W. H. Collins (C.M.S.), who met him as

he entered the city gate, and at once claimed him as a guest. It was not

his object, however, to live with any of the mission families. He wished

a house for himself. A small house with a little selfcontained court was

rented for him at 2s. 6d. a month. Here he lived for four years. This

house had a south exposure. On the west was Mr. Burns’ room, with its

two chairs, table, and khang. This last, used through all the north of

China, is a brick structure at one end of the room, permeated by a

winding flue, and when required can be heated from the front through an

opening partly in the floor, and partly in the brick khang. On the east

side was the servant’s room, used also as kitchen. One servant was

sufficient to buy, to cook, and to keep the house. When the servant went

out, Mr. Burns stayed at home. This simplicity of living was happiness

to our lost friend. He enjoyed quietness, and the luxury of having few

things to take care of. He delighted to live on little, that he might

have more to give to the cause of God. He was a generous friend to the

poor, to hospitals, to various mission schemes.

“In the summer, according to Peking custom, he had an awning of

reed-mats extended over his court. This, in north China, greatly helps

the people to pass the summer in comfort. In the evening the mats of the

awning are drawn open sufficiently to admit the night air. We have a hot

short summer, at an average of 90°, as we have a cold winter averaging

150, when the ice never thaws till the opening of spring, but remains a

foot thick through the season. Our friend had a small clay-stove lit for

the season. Here he sat summer and winter with his teacher, engaged for

a good part of each year in hymn-making and translation.

“His first work in Peking was a volume of hymns, about fifty in number.

These were chiefly translations from home hymns, or hymns used in the

south of China rehabilitated in the mandarin dialect. They have been

extensively used since, and will continue to be so. He usually adopted,

in addition to the seven-foot measure, which is the commonest Chinese

metre, the various measures in which English hymns are composed. He

still speaks to us in our assemblies, and is the mouthpiece of our

praise by these compositions, which gave him much agreeable occupation.

“When he had printed this collection, he undertook a translation of the

Peep of Day in fifty chapters. It treats of man, the creation and the

fall, in nine chapters. The history of Jesus follows, and occupies the

whole work to the forty-sixth chapter. It concludes with four chapters

on pentecost, the deliverance of Peter from prison, the apocalypse of

John, and the last judgment. This excellent little work has been widely

circulated, and is found to form a very suitable introduction to the

gospel history. Mr. Burns omitted some portions of the original, and

substituted new narratives as appeared to him appropriate. At the end of

each chapter there is a short Chinese poem, giving the cream of the

preceding narrative in rhyme, and in a manner to which the natives of

China are very much accustomed in their light literature. This work is

in the Peking dialect.

“The Pilgrim's Progress was his next work. Formerly at Amoy he had

translated this book in a simple style. He now resolved to render it

again into Chinese, adopting the dialect of Peking. The first and second

parts are complete in two thick volumes. Some of the copies are

illustrated with woodcuts. Some additions are found to the text in the

second part, where an attempt has been made to increase the usefulness

of the work to native women by showing the principles that should rule

in Christian marriage.

“Immediately after the completion of this work, he commenced a

translation of the Psalms from the Hebrew. It was published in the

spring of 1867, a year before his death. It is composed in four-word

sentences throughout so as to assume a regular appearance of symmetry;

but this advantage has been gained at the expense of smoothness. To each

psalm' there is an introduction stating the argument. There are also

many text-references to the New Testament and other parts of Scripture.

These additions add much to the value of the book.

“While engaged constantly in these literary enterprises, Mr. Burns never

intermitted preaching when not physically incapacitated for it. He

preached much at the chapel of the London Mission hospital, within two

or three minutes’ walk of his residence. His assistance here was

annually recognized by Dr. Dudgeon in the printed report. He preached

also very frequently at a chapel of Dr. Martin’s outside of the east

gate, and at another more than a mile north of the London Mission

hospital, belonging to the American Board. He also officiated

occasionally at Mr. Collins’ chapel, belonging to the Church Missionary

Society, on the west side of the city. His services at all these places

were very acceptable, and given with the greatest good-will and the most

catholic spirit: he thus aimed at the glory of Christ independently of

his particular denomination, and was in this respect an example worthy

of imitation, for the maintenance of sectarian distinctions in China may

be regarded as almost unnecessary. The truth that we are all one in

Christ Jesus may well unite missionaries of different communions in

heart and practice. Whenever the Church of Christ in China becomes

strong enough to be separated from the British and American missionary

organizations, it will be advisable for then! to unite in one church

system of their own, framed in a manner consonant with Scripture; but

adapted for China, and not modelled after any of the existing sects of

Western Christendom. With this theory Mr. Burns’practice well agreed. He

was at home with all Protestant Christians, and was greatly loved by all

his brethren. His manly character, his sober views, his practical good

sense, his kindly sociality, his mental strength, his moral decision,

and his consistent and unaffected piety made him a friend greatly valued

by us all. We enjoyed his coming to sit in the evenings, to share with

us in his simple abstemious way at the social meal, to unite with us in

family worship, or to join in the exercises of the week-evening

prayer-meeting. He frequently preached in English at the Sunday evening

service, held for the benefit of the mission families, and was always

welcomed as one whose sermons were invariably characterized by solidity

and faithfulness. He impressed his auditors with the fact, ‘that he was

a man of power and devotedness, a man whose atmosphere was prayer, and

whose daily food was Scripture.

“With his large-hearted kindness, and great willingness to do

evangelistic work whenever and wherever there was an opening, he went no

fewer than four times on journeys connected with the country work of the

London Mission at Peking. The first occasion was to Shen-cheu, a city

south-south-west of Peking, and distant 170 miles. He went in response

to an invitation from the people, who wished a preacher to come and tell

them the gospel. He stayed there about three weeks, and when he left

thought that at least two of the natives were suitable for baptism. The

Bible distributor who was with him thought there were four. Mr. Burns

was very cautious in giving an opinion with regard to the fitness of

applicants for baptism. His habit was to be stern in requiring decided

sacrifices on the part of the inquirer, such as should constitute

indubitable proof of his sincerity. It was perhaps this feeling which

prevented his ever baptizing converts. He left that for other

missionaries to do, claiming on all occasions, as an evangelist and not

a pastor, the privilege of exemption from responsibility.

“Another town he visited was Tsai-yii; here he stayed a month on two

occasions. The seeds of the gospel were, at this town, sown by him in

some honest hearts, and grew to maturity after a long period. At that

time the London Mission had a chapel there, with a lodging room annexed

suitable for a missionary. Here he lived and daily preached the Word of

Life. On one occasion a Russian physician went down to heal the sick,

and on this occasion notice was sent previously, and placards were

posted. Not very many patients appeared, and the kind Russian doctor

returned after a few days. While he was there Mr. Burns preached, and

acceded to the request made to him to have his portrait taken. This, it

is believed, was the only time in his life that he consented to be

photographed. It was a few days after his return to Peking that the

likeness was taken by Dr. Pogogeff. It was for his mother’s sake. Had he

not known that she would be especially gratified by a portrait of him,

he would probably have never consented to have it done, dreading the

least appearance of vanity or self-idolatry. The publication of a

woodcut from this picture in Sunday at Home, has made him widely known

in his Chinese costume with shaved head and queue. He adopted this mode

of dress about thirteen years (or fourteen) before his death, when at

Shanghae, on a journey with Rev. J. H. Taylor, now of Yang-chow. He

never urged other missionaries to adopt the Chinese dress, and but few

followed his example. As a rule every man looks best in his own national

dress. It became Mr. Burns, especially in his later life (when his hair

grew nearly white), as well as most persons, although the deep-set eyes

and prominent nose of the European physiognomy prevented him entirely

from ever being taken for a Chinese. But he retained the costume, not

because he felt it to be a duty to conform to the manner of the country,

but from the inconvenience attendant in going back to the European mode.

“On another occasion Mr. Burns went with a catechist and hospital

dispenser to Pan-pi-tien, near the imperial western cemetery. He was

there located in a temple at the invitation of the priest, who had made

an offer of the property to the London Mission to found a hospital. Mr.

Burns, having some knowledge of law, always took an interest in legal

questions, and worked laboriously to arrive at a safe conclusion in all

such matters. Many sick were healed, and to many the gospel was preached

during this visit, but the temple was found not to be the priest’s to

give, and soon after Mr. Burns’ return the negotiation was terminated

abruptly, by the removal of the priest to another temple.

“Mr. Burns held very distinct and decided views on the most appropriate

word in the Chinese language for God in the Christian sense. Without

saying categorically that the Shang-ti of the Chinese classics is the

‘true God,’ he held that this term is the most appropriate to be used,

on account of its being the most correct, distinct, noble, and

unmistakeable word to be found. When in Peking an attempt was initiated

to unite all Protestant Christians in China in the use of one term, and

that the Roman Catholic term, Tien-chu, Lord of heaven, he withheld his

consent, and was at the time the only Protestant missionary in Peking

who did so. Thus for the whole of his long missionary course, of more

than twenty years, he adhered steadily to the use of the term which has

been adopted by the British and Foreign Bible Society, and is most

extensively used in the Protestant missions.

“The change proposed extended only to the use of the Roman Catholic term

in a single version, namely, that in the colloquial mandarin dialect,

but it met with little favour in the southern stations, and is now

supported by very few.

“Strongly as he felt in regard to the use of the proper terms to be

employed for God and for the Holy Spirit, he would, when preaching in

the chapels of those missionaries whose views differed from his own,

modify his phraseology so as to suit his peculiar position at the time.

His broad and manifest charity, won fo him all his brethren.”

In the autumn of 1867, left Peking, urged forward as usual by the

necessity that he ever felt laid upon him, of withdrawing from a field

which was comparatively well occupied and cared for, and proceeding to

others more neglected. His life at Peking had been peculiarly pleasant

to him, and his friends and his work congenial; but he was all the more

prepared to hear the voice that summoned him to a sterner and more

self-denying service elsewhere. For the following account of the

circumstances of his departure, and of his journey to Nieu-chwang, I am

again indebted to Mr. Edkins’ graphic pen:—

“Wang-hwan who was baptized by me in Peking four years ago, is a native

of a village about thirty miles from Peking, and six miles from Tsai-yii,

where at that time the London Mission had a chapel. He heard Mr. Burns

occasionally at Tsai-yii, and was afterwards brought to decision for the

gospel in connection with the work of one of our catechists, for a time

in charge at the chapel at Tsai-yii, and who is now dead. Wang-hwan

became a changed man, and after his baptism in the hospital chapel,

Peking, appeared to his neighbours a very different person from what he

once •was. They saw in him a man peaceable and well-behaved, whereas he

had once been the opposite.

“Mr. Burns took him with him after much consideration, and was

influenced more by satisfactory evidence of deep interest in religion

and a love for prayer, than by any ability that he showed. He had had

the education of a small country farmer, that is three or four years’

schooling, just enough to enable him to transact ordinary business.

Since that time he has improved himself. When Mr. Burns left Peking for

Tientsin, in the autumn of 1867, it was still an open question whether

he would go to Nieu-chwang or to Shantung. I had been laying before him

a request from Shantung from several persons for a preacher. If he had

gone there he" would have passed through the villages where the

Methodist New Connexion Mission and our own are situated, and his

experience in manifestations of the spiritual life both in Christian

countries and in China would have rendered his testimony to the

character of these Christians one of great value.

“But his sense of duty and his knowledge of the need of a missionary at

Nieu-chwang, led him there in preference. The captain of the native junk

in which he went would take no money from him for the passage. This was

on account of his character, and that of the catechist. Going not for

trade but to do good, it appeared to this heathen sailor unreasonable to

accept payment of passage money. Arrived at Nieu-chwang they began to

seek a house, and found one at last in the outskirts. Here they became

domiciled, and public and private services were daily held. Many persons

attended, and the hearts of our departed brother and of the catechist

were cheered.

“On Sundays Mr. Burns performed worship in English at the consulate as

long as his health allowed.”

Of the general course of his life and labours during the few remaining

days of his earthly ministry, the following brief recollections of the

mate of a trading vessel which happened at that time to touch at the

port of Nieu-chwang, afford an interesting and life-like glimpse:—

“In October, 1867,” says this Christian seaman, in a communication

printed in the Sunday at Home, “I left Che-foo, in the barque Lady

Alice, for Nieu-chwang, where we arrived about the 6th. 1 had learned

from the missionaries at Che-foo that a missionary of the name of Burns

was at Nieu-chwrang. The first Lord’s-day after arrival our captain and

second mate went on shore to the British consul’s office. This was the

only place for worship at Nieu-chwang, except the meeting on 'board our

vessel. It being the second mate’s turn on shore, I told him if the

minister was dressed like a Chinaman, to introduce himself to him, and

deliver a message for me. On his return at dinner-time I was much

cheered and delighted to hear that it was Mr. Burns that held the

service, and that the service was no formal ceremony, nor with enticing

words of man’s wisdom, but very earnest and very faithful, warning them

to attend to the salvation of their souls, and commending godliness as

profitable in all things. After the service my friend carried out my

wishes, and met a hearty welcome from Mr. Burns, who was himself cheered

at hearing there were some belonging to our ship professing to be the

ransomed of the Lord, and trying in some feeble way to acknowledge him

and commend him to others.

“He sent me an invitation to come and see him on a certain day of the

week, I forget now which day. His Chinese servant was to meet me on my

landing, and conduct me to him. I landed at the appointed time, and was

conducted accordingly to the missionary I had never seen. I shall not

soon forget it, for we seemed to meet as friends that had been

acquainted for a long time. I felt perfectly at home with him. Mr. Burns

walked up and down the yard of his house arm-in-arm with me, and talked

to me as a friend, brother, or father, in the most kind and familiar

manner. As iron sharpeneth iron, so did the countenance of a man his

friend that day.

“He told about how the Lord had guided him to that place (Nieu-chwang).

He had many friends, he said, where he had been staying for four years

before, and was very comfortable; but he wanted to come to Nieu-chwang

because there was no one labouring there. He said we must not study

comfort: they that go to the front of the battle get the blessing; the

skulkers get no blessing. I have often thought of that since, for indeed

it was a word in season to me at the time. He told me how he arrived

there in a junk, or native vessel, and how kind they were to him, and

how he had been guided to the house he was then living in. He spoke as

seeing the dealing of God in his providence in all his ways. . . .

“It was a very happy time, I think, to both—a time of refreshing. I did

not stay late, as I had some mile and a half to walk. The Chinaman again

conducted me back. We started with the understanding that Mr. Burns was

to visit our ship, I think the next evening; so when I got on board I

obtained permission from the captain for us to hold a meeting in the

cabin. I hoisted my Bethel flag in the afternoon, and when our friend

came on board we told him we had the royal standard flying, ‘for I

suppose you belong to the royal family.’ He took tea with me and the

second mate (the captain was on shore), and in the evening, when all the

crew were with us, he gave an address about the Saviour and the woman of

Samaria. There was one illustration I remember which shows his homely

and forcible way of putting things. He compared the woman of Samaria to

a fish with the hook in its mouth, twisting about, trying to get loose;

but the more it tried to clear itself the firmer hold the hook got of

it. The whole of the address was very interesting and very earnest, and

was well received.

“After he had done, he requested one of us to engage in prayer. Our

cook, a black man, by the name of Caesar, offered a very earnest prayer.

It was, indeed, pleasant, in this dry and barren land, thus, for a short

time, to dwell together in unity. After our meeting was ended not one

offered to move; and our dear friend, sitting at the head of the table,

told us about his travels in China, and of his being taken prisoner with

two Chinese converts, and sent through the country, with many other

things which are probably well known. Thus our time soon flew away, till

the parting had to take place. Our cook had a set of Wesleyan

hymn-books, which we used for worship. He sent Mr. Burns one, with which

he was very pleaded, and talked of translating it into the Chinese

language. This was one of the happiest evenings of our voyage. ... He

spoke to me very affectionately about his mother, and most of his

affairs. When the time drew near for us to part he handed me the Bible

and bade me read something. I read the 103d Psalm, and could not help

(nor need I try to) giving vent to my feelings while reading it, there

seemed such a blessing flowing from it. It was like the river whose

streams make glad the city of God. I think we could set to our seal that

the word of God is true. After we had prayed, Mr. Burns said, ‘The Lord

is nigh to all that call upon him;’ and we both joined in saying, ‘to

all that call upon him in truth.’ . . .

“When parting I spoke to him of his kindness, and the great honour I had

received from him, when he put his arms around me, and said, ‘Don’t

mention it, don’t mention it! Our meeting is providential.’ Thus we

parted. The Chinaman again conducted me back in the beautiful still

moonlight. I cannot attempt to describe the sweet and blessed meditation

I had while returning to my ship. I have thus simply spoken of my

meeting, intercourse, and parting with a blessed man of God, the

remembrance of which is still dear and sweet to me. I have good reasons

to look back to this time, and praise that God who has been so merciful

to me in all my wanderings. Mr. Burns was a saving shield to me in God’s

providence at that place, and as an angel of the Lord.

"Blest be the tie that binds

Our hearts in Christian love."

‘By this shall all men know ye are my disciples, if ye love one another;

and every one that loveth him that begat loveth him that is begotten of

him.’ Mr. Burns was an Israelite indeed. . . .

“He then seemed,” wrote Caesar the black cook in a postscript to the

above, “to me to have been well advanced in years. Nevertheless he moved

about and spoke the Word of Life as brisk as can be expected from a man

of thirty years of age. He said we all wanted stirring up; and so he did

stir us up on board of the ship, for he made a lasting impression on my

mind. He spoke freely and boldly about the changes pertaining to that

world which is to come. He put me in mind of one who had already gone

through his refining process. He appeared then to be ripe for glory, if

we may use the term, and I feel sure that he is ‘gone home’ to the city

of the living God, and to Jesus the Mediator of the new covenant, who

was waiting, no doubt, to welcome his ransomed and faithful one. He gave

me the Pilgrim's Progress that he translated while he was out there,

from English into the Chinese language. His last words to me were, ‘Pray

for me.’ He also wrote the words down on the book he gave me, so that I

should not forget. Last night, unknowingly,1 I prayed for him for the

last time. So now my prayers cease from last night, and turn to praise;

and I shall expect to meet him face to face.”

On the 21st November, he wrote the following lines, breathing his usual

cheerful and happy spirit, to his valued colleague, Mr. Douglas, one of

the last letters of any length he ever wrote on earth:—

*Not knowing of his death.

"Nieu-chwang) November 21st, 1867.—Dear Mr. Douglas, —Your letter of

August 31st reached me this P.M. per steamer Manchu, and as she is the

last vessel for this season, I hasten to send a few lines by her to

Shanghae. Many thanks for the life-like photograph of yourself which you

have sent me. You are more like the man that you were intended to be

with than without the ‘beard.’ May it please God in his mercy long to

preserve you in the health and vigour which you seemed to have enjoyed

when the likeness was taken, and may your soul ‘prosper and be in

health,’ even as the body ‘prospers!’ For the last five months, I have

allowed my ‘beard’ also to grow on the lower part of the face. This both

saves a great deal of time and trouble, and, in this cold latitude, the

hair is a protection to the throat. I fear I cannot write home pressing

the claims of Singapore on our mission, when their energies are likely

to be fully tasked in maintaining and extending the missions at Amoy,

Swatow, and on Formosa. It seems to me that no place more suitable (or

perhaps so suitable) could be recommended to the Irish Presbyterians

than Nieu-chwang, and Manchuria beyond, a vast, open, and unoccupied

field, with a fine climate, and a population comparatively well off in a

worldly point of view. In writing home, I have already made this

suggestion, and I hope that on consideration you will see your way to

second my proposal. If the Irish were here, would this not be a fine

place to come to from the south for a change of air? and you yourself,

when needing such a change, would enjoy the opportunity of using and

increasing your Mandarin. Mr. Cowie, too, would be only sent back to his

Che-foo dialect, a great part of the people in this town being from that

quarter. You can have no idea of the extent of the trade that is carried

on here in grain and oil, as well as bean-cake, furs, &c. &c. I shall

only mention what was told me by a gentleman connected with the imperial

customs, viz.: that two years ago it was estimated that during one

winter 80,000 carts came to this place from the interior laden with

grain and oil. It is common for from 500 to 1000 to come in on a single

day during the winter months; and throughout all the region which

furnishes this supply, including the provinces of the Amour and Kirin,

as well as the province of Kwan-tung, pure Mandarin is universally

spoken. Mr. Meadows is now absent on a three months’ journey to the

north and east, passing through the centre of these three provinces.

Romish priests are found here and there, but the only representative of

the Protestant churches is my solitary self! I lately heard from Mr.

Grant, and also from Si-boo. Mr. G. has now removed to Singapore from

Penang, and so Singapore is not so destitute as it used to be. Mr. G. is

married too, to a lady who lately came out, as perhaps you may have

heard. As to the repairs at Pechuia, I shall be glad that you put me

down, say, for the sum of 1900 sterling, but it will be the end of

February before I can furnish you with an order on our treasurer for

that amount, my accounts for the year being already made up. I am

rejoiced to hear that while man is repairing the chapel, God himself is

again graciously putting forth his hand to repair the spiritual walls of

that little church. May backsliders return to their first love, as well

as additions be made to the church of ‘such as shall be saved!’ Who was

that young man—an assistant of Dr. Maxwell’s —who was lost in the

Formosa Channel? Not, I hope, the young man from Chidh-bey, who was

afterwards chapel-keeper at Sin-koeya? I must now conclude, as it is

getting late. Pray for us, and commend us to the prayers of the

churches. I should have mentioned that Mr. Williamson of Che-foo, who

was lately here, left a native assistant to sell books here during the

winter. He and the man who came with me from Peking occupy themselves in

this work in the principal street, preaching at the same time to the

people. I join them generally during a part of the time, and the

opportunity is a valuable one, especially as our house is too retired

for collecting passers-by. A separate house we thought we had got for

preaching was'at last held back, and is now an opium-smoking den!

Christian love to all the brethren. Yours affectionately ,-Wm. C.

Burns.”

The following letter, which came to me altogether unsought, just as I

was approaching this part of my task, will tell almost all that now

remains to be said, and in terms than which the fondest affection could

have desired nothing more loving or tender:—

“Nieu-chwang, 6th July, 1869.—My dear Sir,—When in conversation with an

intimate friend of your late brother the Rev. Wm. C. Burns, I related

the particulars of my last interview with him, which occurred a few days

before his death ; and as far as I know, the last hour when he was in

full possession of his faculties. I was then informed that you were

gradually collecting material for a book which should illustrate his

missionary labours in China, and was pressed to repeat to you what I

knew of his closing life. This is difficult to do in a letter; it is

difficult to express in writing what I might so easily relate to you by

word of mouth, without entering rather at length into his previous life,

i.e. at this port. As you are aware, it was in August, 1867, that he

arrived at Nieu-chwang; for the purpose, as he then said, of seeing what

could be done toward establishing a mission in the province of

Manchuria. He was accompanied by a native Christian of Peking to assist

him in his labours. With them they brought only their personal clothing,

and Bibles and books for distribution. I had never seen your brother

before; but at my first interview Was impressed with the earnest

simplicity of his manner, and the cheerfulness which I afterwards

noticed he at all times carried with him. A few days after this I went

to visit him in the native town at a small inn where he was then

staying. I found him lying down in a very small apartment, which was

destitute of every comfort. He was ill, but arose to meet me. He would

allow no expressions of pity for the want of these comforts, and soon

made me forget them in listening to the history of his labours at

Peking, while making translations of various works. I was from that

moment very fully impressed with the genuineness of the love which had

actuated his motives in devoting his life to the work of a missionary. A

little later on he had found a house wherein to begin his labours. His

days were spent in preaching to the inhabitants in the streets,

distributing and selling books. Sundays, he preached to the foreigners

in the foreign settlement in the forenoon; and in the afternoon to the

natives at his house, which for all intents and purposes was recognized

as the Christian chapel. It was delightful to see how faithfully he

performed his duties,—how on every Sabbath morning he appeared in our

settlement punctual to the hour, having to come nearly two miles through

the heat, and through the cold, and often to encounter the bad roads of

the country. By his kindly manner, his spotless reputation, his

Christian earnestness, he drew a goodly number to listen to him. As he

talked on, his face became all alive with the deep faith he had in the

truths he endeavoured to communicate; and his face often and often

became radiant with a light, revealing the love which warmed him into

eloquence. He seemed to possess a zeal which might have belonged to the

earlier days, when apostles went forth so fearless and with so much

love. One could not but observe this peculiar power which he possessed.

For a moment he would speak with great force, and then change to tones

of gentleness which were as impressive as they were childlike in their

utterance. All this and far more you must know. Observing these

characteristics, led me to have confidence in the impressions he was

likely to give to the natives. Even in the short time he spent among

them here, a few learned to inquire into the Christian doctrines.

“Early in January he was taken ill with a cold which brought on fever,

from which he never recovered. For weeks and months he lingered in

helpless weakness. I went to see him often. One day he said, ‘ I have

been thinking that perhaps this is to be my last illness.’ From that

time he frequently told me of his hopes and his fears. As he lay upon

his bed, he thought out his plans for the future, and his sole desire to

live seemed to be that he might labour to carry them out for the good of

those he had come among. For a long time he would insist upon his

assistant preaching in the next room, that he might listen. And nearly

up to the time of his death, he would have him and his servant—who

by-the-by was becoming a Christian through his teaching— conduct the

morning and evening prayers by his bedside. When he spoke of life, he

said what he himself would do.

When he spoke of death, he prayed that others might be found to continue

the work he had begun. When talking of either he was equally

resigned—always cheerful, always happy. If he had fears at all, they

must have' appertained more to the things of this world than to the

other. And in preparing for this, he was preparing for the other. You

know how he arranged for the support of his native assistant after his

death, and until such a time as a foreigner should arrive. I will not

therefore repeat.

“And now I come to speak of the last hours. One evening about six

o’clock, I went to see him. I found him suffering from hard and

difficult breathing, and I felt that death was near. So I sat by him and

talked of the hour which was coming—of the life which was beyond. In

reply to my inquiry whether there was anything I could do for him after

he was gone, he said, ‘No, I have arranged everything; all I have to ask

is that you will keep your promise in regard to my wishes for this

mission.’ I began to repeat to him familiar passages from the

Scriptures, in which he joined as often as his strength would allow; he

would listen until I came to the lines which he loved the most, when he

would say them aloud, his voice though very low, yet singularly deep.

When I began the psalm, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd,’ a beautiful smile

broke over his countenance and he pressed my hand more firmly; and his

voice assumed, with all its weakness, something of the old depth as we

came to the words, ‘Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of

death I will fear no evil.’ When with much fervour he had repeated the

Lord’s Prayer, we sat in silence. He assured me he was very happy. And

thus he died, as it were, among the people with whom he had cast his

lot; indeed we might almost say among the very scenes with which he had

identified his life. One who could have watched his declining days when

he naturally, more or less, gave expression to his views, would have

marked with interest the contrast between the mind and thoughts so

trained to higher themes, and the heart so contented with lowly things.

The little room in which he died had but few comforts, certainly no

luxuries. The form on which he slept, a table, two chairs, two

book-cases, and an open-grate, foreign stove made up the furniture. The

light came into the room through a large paper window. But I shall long

remember the solemn hour which I have endeavoured to describe to you.

The assistant sat at his feet weeping, now and then raising his eyes

upward in silent prayer, and the servant on one side watching with

tenderness his wants. And these two simple-minded natives, judging from

their life and sayings since, must have profited by his last

injunctions. And so after the years of toil he passed away into the

other world. ‘God,’ he said, ‘will carry on the good work.’ ‘Ah! no, I

have no fears for that.’

“It was a rare privilege to have known your brother. His firmness of

purpose was remarkable; his Christian faith supporting to himself, as

well as encouraging to others; his gentleness most touching; his

happiness genuine. And to me these incidents which I have related

contain more than I am able to express.”

One or two further touches from like loving hands will complete the

picture of this calm and radiant sun-setting. The following

reminiscences of his humble native assistant,

Wang-hwang, have been kindly furnished to me by Mr. Edkins, who took

them down from his own lips:—

“While he was here,” says Mr. Edkins, in continuation of the notes

already quoted, “ I questioned him about Mr. Burns’ last words of

testimony to the gospel, in the service of which he lived and died. What

he said is here appended. ‘It was the 28th day of the 7th (Chinese)

month when we arrived, and we were five days waiting at Takoo (the port

at the mouth of the Tien-tsin river). While there we went daily from our

boat to preach in the streets. When we went on board the junk, the

captain declined to attend our services; but on the third day he and

"the two cooks joined us. When Mr. Burns offered him passage-money, the

captain said, ‘I know you are not going to seek gain, for in that case

you would certainly travel by steamer, or by a foreign sailing vessel.’

He belongs to a fishing village called Tien-kia-tsui, a few miles north

of Takoo on the coast.

“‘We went on well till the 16th day of the 12th month. On this day Mr.

Burns was taken ill, and lay for ninety-four days, when his spirit fled.

He had felt pleasure in preaching that day. Many foreigners were

present, which rejoiced him. When he came back from the English service,

and saw sixty or seventy Chinese pressing in to hear, he said, ‘ I will

preach to them.’ He preached for two hours. After this he felt no

appetite, took no food, and lay down weary. About eleven o’clock p.m. he

waked shaking with cold. For twenty days after this he did not leave the

house. When prayer time came, he said, ‘ Come to my bedside, I will

still preach to you.’ So the little band of inquirers gathered with

Wang-hwan round the sick missionary, for whom it was appointed that he

should soon go home.

“When his illness became severe, he made me promise that I would stay at

Nieu-chwang. When we left Peking he was afraid, he told me, lest he

should take the wrong man, a man different in mind and aim to himself. I

said I would certainly stay at Nieu-chwang and carry out his

injunctions. ‘But/ he said, ‘you have no strength or learning, and you

must therefore be the more careful to be right, and to do what is right,

so as to secure favour from God and approval from man. You must pray

much for aid.’

"One time when his sickness was severe he lay as if asleep, when in a

moment I heard him talking. I asked him what he was saying. He replied,

‘Ah! did you hear ? I was saying over the 121st Psalm. I was speaking

with God, not with you.’

“‘Another time he laughed. I asked him why? He said,

‘God was speaking with me, and this made my heart glad.’

“‘Two days later, he said to me, ‘God tells me to go. I have some things

to say to you. As to my burial, 1 wish to have no new clothes bought,

but to be buried in these.’ (Referring to his Chinese clothing. The

custom of the country is to buy a new suit, and lay the deceased in his

coffin with complete dress as if living. It is quite a common thing to

draw on the new clothing some hours before the death takes place.) He

further said, ‘ Do not let the funeral be on Sunday. At the burial read

1 Cor. 15th chapter. Pray with the inquirers. Tell them to be sure to

come and see me again in the place to which I am going. Do not weep

after my death. Do not pray for me, but pray for the living. Diligently

pray, and God will certainly send you a missionary.’

“At another time, when he was a little better, a letter came from his

mother. It said, ‘Do not think of me, but of your work.’ He told me what

his mother said, and her words rejoiced him greatly. He added, ‘She says

I am a knife that must be worn out by cutting, not by rusting.’ He

wished it might be so. He also said, ‘ I am one of four brothers’ (or ‘

I have four brothers’), ‘one of them I would wish to exhort, -but I

shall not now have the opportunity. I hope others may do so.’

“‘He urged me to believe as he did, pray as he did, read diligently as

he did, and use my mind as he did, ‘and,’ said he, ‘God will help you to

preach.’

“‘If you are reproached, bear it patiently. To be patient is to glorify

God. I was not sorry when in the south the time of suffering came, nor

should you be. Think of what some missionaries have had to suffer, and

such things should rather be rejoiced in as proof of God’s care.

“‘You can be my substitute when the new missionaries come. I cannot be

here to receive them. You can do so, and must act for me. You must have

the same heart as I have.

“‘I felt in Peking that my work there was done. It was a trial to leave

friends. Yet for the gospel I could not but go. We shall meet again in

heaven; and think of the knife. You must be one of God’s knives.

“‘If there are inquirers, you must be careful to lead them -in the right

path, remembering that you are yourself not very strong nor learned.

Take care to be diligent. Be indulgent to inquirers, exhort them much,

and be very mindful of the example you set them, lest you should

dishonour your Saviour, and cause sorrow to your pastor and friends.

Always think of this.

“‘I am very happy. I do not fear death. After death there is unspeakable

happiness to be hoped for. Do not think I am sad at the thought of

dying. I am not at all so. God’s promises are true, and I fear not. My

work has been little, but I have not knowingly disobeyed God’s

commands.’

“‘The inquirers, five or six in number, went in to see him. He said,

‘You see in me proof that the Christian doctrine is true. I am well

supported now, and this strength which is given me, not to shrink at the

approach of death, you can take as proof that what I believe is true; my

illness, my decaying body, are also a testimony to the truth of the

Bible. When I am gone you will have no missionary here. You must

therefore pray much and think and read much that you may understand

well. I have left friends and home to come here for the sake of this

gospel that now supports me. I rely on God now. Listen you to him, and

let us resolve all to meet in heaven. Hope for this. Live for this.’”

It was in the midst of this “time of languishing,” and when the shadows

of the great night began visibly to close around him, that he wrote in

his own hand, still clear and strong as of old, the following touching

lines to his mother—embodying his last solemn testimony in behalf of

Christ, and of that great cause to which he had devoted his life:—

“To my mother.

“At the end of last year I got a severe chill which has not yet left the

system, producing chilliness and fever every night, and for the last two

nights this has been followed by perspiration, which rapidly diminishes

the strength. Unless it should please God to rebuke the disease, it is

evident what the end must soon be, and I write these lines beforehand to

say that I am happy, and ready through the abounding grace of God either

to live or to die. May the God of all consolation comfort you when the

tidings of my decease shall reach you, and through the redeeming blood

of Jesus may we meet with joy before the throne above!—Wm. C. Burns.

“Nieu-chwang, Jan. 15 th, 1868.

“P.S.—Dr. Watson is very kind, and does everything in his power for my

recovery.”

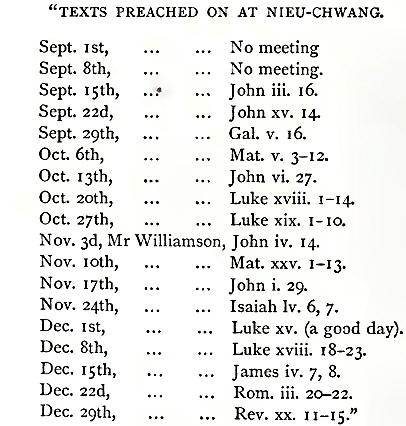

To this is attached on a small fragment of Chinese paper, also in his

own hand—a list of the texts on which he had preached at Nieu-chwang,

from a tender feeling obviously that she to whom he wrote would like to

see it. Perhaps there are other eyes that may linger over the lines with

mournful interest. It will be observed that the first two Sabbaths are

blank, in consequence of the suffering and enfeebled state in which he

arrived from Peking.

Thus his last public

testimony was to the same great truth of which he had witnessed so

powerfully on the streets of Newcastle twenty-seven years before, and

the overwhelming conviction of which had so often imparted an almost

preternatural terribleness and grandeur to his words.

The tide of life now gently ebbed away. He spoke little even on those

subjects that were dearest to him, lying for long days and nights in

silence that was broken only by the soft footsteps of his Chinese

assistant, and by the voices of the worshippers from time to time in the

neighbouring room, in which it was his delight to know that his loved

work was still carried on. His peace was calm and deep, but

undemonstrative—like that of the river which speaks only by its silence

and by the soft whispering of the reeds and lapping of the waters on its

banks. “He did not speak much,” wrote the Rev. A. Williamson, “on

religious subjects either to Chinese or foreigners; and when he did, the

burden of his remarks was that he was prepared to die or to live as the

Lord might determine.” “About a month after the commencement of his

illness,” says another friend who often visited him at this time, “he

began to apprehend its fatal issue, but said he was quite prepared.

After six weeks or so, his fresh looks began to leave him. The

brightness of his eye faded, and gradually he became like an old

decaying man.” Yet now and then the old fire would for a moment awake,

and impart an expiring energy alike to his voice and his frame. “Finding

a decided change for the worse, and great distress in breathing, the

gentleman just referred to repeated several portions of Scripture, among

others Psalm xxiii. Hesitating at the words, ‘Yea though I walk through

the valley of the shadow of death/ Mr. Burns took it up, and in a deep

strong voice continued and finished the psalm. He also greatly-relished

John xiv., ‘Let not your heart be troubled,’ and on closing the exercise

with the Lord’s Prayer Mr. Burns suddenly became emphatic, and repeated

the latter portion and doxology, ‘For thine is the kingdom, and the

power, and the glory,’ with extraordinary power and decision. This was

the last time he manifested any power of mind. Afterwards he only

evinced recognition, and at last hardly spoke or even opened his eyes.

Thus he passed away.” .

This is the last glimpse we have of him ere he passes out of sight. On

the afternoon of the day on which he died, the kind doctor who had so

tenderly watched over him throughout, hearing that he was worse,

hastened, in company with the consular assistant, to his bedside, but

just too late to see him die, though the heart and pulse were still

beating when they arrived.

He was buried in the foreign graveyard, according to the simple rites of

the Presbyterian Church, Dr. Watson, according to his own express

desire, reading those grand words in i Cor. xv. 42-57: “So also is the

resurrection of the dead; it is sown in corruption, it is raised in

incorruption : it is sown in dishonour, it is raised in glory: it is

sown in weakness, it is raised in power: it is sown a natural body, it

is raised a spiritual body. There is a natural body, and there is a

spiritual body. And so it is written, The first man Adam was made a

living soul, the last Adam was made a quickening spirit. Howbeit that

was not first, which is spiritual, but that which is natural; and

afterward that which is spiritual. The first man is of the earth,

earthy; the second man is the Lord.from heaven. As is the earthy, such

are they also that are earthy; and as is the heavenly, such are they

also that are heavenly. And as we have borne the image of the earthy, we

shall also bear the image of the heavenly. Now this I say, brethren,

that flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God; neither doth

corruption inherit incorruption. Behold, I show you a mystery; We shall

not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the

twinkling of an eye, at the last trump, (for the trumpet shall sound;)

and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed. For

this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on

immortality. So when this corruptible shall have put on incorruption,

and this mortal shall have put on immortality, then shall be brought to

pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory. O

death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory? The sting of

death is sin; and the strength of sin is the law. But thanks be to God,

which giveth us the victory, through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

It was a dreary and desolate place, and the river was fast washing it

away, but Dr. Watson informs me in his last letter that the precious

dust has been since removed to a piece of ground recently purchased by

the foreign residents for a cemetery. “We. hope,” says he, “to make our

new burying-ground somewhat like such a place at home, where

occasionally we may walk, and call back to memory the lives of those we

loved.” There the place of his grave is marked, according to the terms

of his will, by a modest head-stone, bearing the following simple

legend:—

TO THE MEMORY

OF THE

REV. WILLIAM C. BURNS, A.M.,

MISSIONARY TO THE CHINESE,

From the Presbyterian Church in England.

Born at Dun, Scotland, April 1st, 1815.

Arrived in China, November 1847.

Died at Port of Nieu-chwang,

4th April, 1868.

His beloved colleague Mr.

Douglas, who on hearing of the critical nature of his illness, had

hastened from Amoy, that he might minister to him in his time of need,

found on his arrival that he had already—two months before—. passed

away, leaving behind him a general sentiment of deep and reverential

sorrow both among the European and native residents, conspicuous among

whom was his faithful assistant Wang, who still wore the long queue and

the unshaven beard, after the manner of his people in their deepest

mourning for a father or a mother.

|