|

Lord Elgin assumed the governor-generalship of

Canada on January 30th,

1847, and gave place to Sir Edmund Head on December 19th, 1854. The address which he received from the Canadian

legislature on the eve of his departure gave full expression to the golden

opinions which he had

succeeded in winning from the Canadian people during his able administration of nearly eight years. The

passionate feeling which had been evoked during the crisis caused by the

Rebellion Losses Bill had gradually given way to a true appreciation of the

wisdom of the course

that he had followed under such exceptionally trying circumstances, and to the general conviction that his strict

observance of the true

forms and methods of constitutional government had added strength and dignity to the political institutions of the

country and placed Canada at last in the position of a semi-independent

nation. The charm of his manner could never fail to captivate those who met

him often in social

life, while public men of all parties recognized his capacity for business, the sincerity of his convictions, and

the absence of a spirit

of intrigue in connection with the administration of public affairs and his relations with political parties.

He received evidences on

every side that he had won the confidence and respect and even affection of all nationalities, classes, and

creeds in Canada. In the

very city where he had been maltreated and his life itself endangered, he received manifestations of approval

which were full

compensation for the mental sufferings to which he was subject in that unhappy period of his life, when he proved so

firm, courageous and

far-sighted. In well chosen language--always characteristic of his public addresses--he spoke of the cordial

reception he had met with, when he arrived a stranger in Montreal, of the

beauty of its

surroundings, of the kind attention with which its citizens had on more than one occasion listened to the advice he

gave to their various

associations, of the undaunted courage with which the merchants had promoted the construction of that great road which

was so necessary to the

industrial development of the province, of the patriotic energy which first gathered together such noble specimens

of Canadian industry

from all parts of the country, and had been the means of making the great World's Fair so serviceable to

Canada; and then as he

recalled the pleasing incidents of the past, there came to his mind a thought of the scenes of 1849, but the sole

reference he allowed

himself was this: "And I shall forget--but no, what I might have to forget is forgotten already, and therefore I

cannot tell you what I

shall forget."

The last speech which he delivered in the

picturesque city of Quebec gave such eloquent expression to the feelings with

which he left Canada, is

such an admirable example of the oratory with which he so often charmed large assemblages, that I give it

below in full for the

perusal of Canadians of the present day who had not the advantage of hearing him in the prime of his life.

"I wish I could address you in

such strains as I have sometimes employed on similar occasions--strains suited to a

festive meeting; but I

confess I have a weight on my heart and it is not in me to be merry. For the last time I stand before you in the

official character which

I have borne for nearly eight years. For the last time I am surrounded by a circle of friends with whom I have

spent some of the most

pleasant days of my life. For the last time I welcome you as my guests to this charming residence which I have

been in the habit of

calling my home.[23] I did not, I will frankly confess it, know what it would cost me to break this habit, until the

period of my departure

approached, and I began to feel that the great interests which have so long engrossed my attention and thoughts were

passing out of my hands. I had a hint of what my feelings really were upon

this point--a pretty

broad hint too--one lovely morning in June last, when I returned to Quebec after my temporary absence in England, and

landed in the coves

below Spencerwood (because it was Sunday and I did not want to make a disturbance in the town), and when with the

greetings of the old

people in the coves who put their heads out of the windows as I passed along, and cried 'Welcome home again,' still

ringing in my ears, I

mounted the hill and drove through the avenue to the house door, I saw the drooping trees on the lawn, with every one of

which I was so familiar,

clothed in the tenderest green of spring, and the river beyond, calm and transparent as a mirror, and the

ships fixed and

motionless as statues on its surface, and the whole landscape bathed in that bright Canadian sun which so seldom

pierces our murky

atmosphere on the other side of the Atlantic. I began to think that persons were to be envied who were not forced by

the necessities of their

position to quit these engrossing interests and lovely scenes, for the purpose of proceeding to distant lands,

but who are able to

remain among them until they pass to that quiet corner of the garden of Mount Hermon, which juts into the river and

commands a view of the

city, the shipping, Point Levi, the Island of Orleans, and the range of the Laurentine; so that through the dim watches

of that tranquil night

which precedes the dawning of the eternal day, the majestic citadel of Quebec, with its noble tram of

satellite hills, may seem to rest forever on the sight, and the low murmur of

the waters of St.

Lawrence, with the hum of busy life on their surface, to fall ceaselessly on the ear. I cannot bring myself to

believe that the future

has in store for me any interests which will fill the place of those I am now abandoning. But although I must

henceforward be to you

as a stranger, although my official connection with you and your interests will have become hi a few days matter of

history, yet I trust

that through some one channel or other, the tidings of your prosperity and progress may occasionally reach me;

that I may hear from

time to time of the steady growth and development of those principles of liberty and order, of manly

independence in combination with respect for authority and law, of national

life in harmony with

British connection, which it has been my earnest endeavour, to the extent of my humble means of influence, to implant

and to establish. I

trust, too, that I shall hear that this House continues to be what I have ever sought to render it, a neutral

territory, on which persons of opposite opinions, political and religious, may

meet together in harmony

and forget their differences for a season. And I have good hope that this will be the case for several

reasons, and, among

others, for one which I can barely allude to, for it might be an impertinence in me to dwell upon it But I think

that without any breach

of delicacy or decorum I may venture to say that many years ago, when I was much younger than I am now, and

when we stood towards

each other in a relation somewhat different from that which has recently subsisted between us, I learned to look

up to Sir Edmund Head

with respect, as a gentleman of the highest character, the greatest ability, and the most varied accomplishments and

attainments. And now,

ladies and gentlemen, I have only to add the sad word--Farewell. I drink this bumper to the health of you all,

collectively and

individually. I trust that I may hope to leave behind me some who will look back with feelings of kindly recollection to

the period of our

intercourse; some with whom I have been on terms of immediate official connection, whose worth and talents I have had the

best means of

appreciating, and who could bear witness at least, if they please to do so, to the spirit, intentions, and motives with

which I have

administered your affairs; some with whom I have been bound by the ties of personal regard. And if reciprocity be

essential to enmity,

then most assuredly I can leave behind me no enemies. I am aware that there must be persons in so large a society as

this, who think that

they have grievances to complain of, that due consideration has not in all cases been shown to them. Let them believe me,

and they ought to

believe me, for the testimony of a dying man is evidence, even in a court of justice, let them believe me, then, when

I assure them, in this

the last hour of my agony, that no such errors of omission or commission have been intentional on my part.

Farewell, and God bless

you." Before I proceed to review some features of his administration in Canada, to which it has not been possible to do

adequate justice in

previous chapters of this book, I must very briefly refer to the eminent services which he was able to perform for

the empire before he

closed his useful life amid the shadows of the Himalayas. On his return to England he took his seat in the House of

Lords, but he gave very

little attention to politics or legislation. On one occasion, however, he expressed a serious doubt as to the

wisdom of sending to

Canada large bodies of troops, which had come back from the Crimea, on the ground that such a proceeding might complicate

the relations of the

colony with the United States, and at the same time arrest its progress towards self-independence in all matters

affecting its internal

order and security.

This opinion was in unison with the sentiments

which he had often

expressed to the secretary of state during his term of office in America. While he always deprecated any hasty

withdrawal of imperial

troops from the dependency as likely at that time to imperil its connection with the mother country, he believed

most thoroughly in

educating Canadians gradually to understand the large measure of responsibility which attached to self-government.

He was of opinion "that

the system of relieving colonists altogether from the duty of self-defence must be attended with injurious

effects upon themselves." "It checks," he continued, "the growth of national

and manly morals. Men

seldom think anything worth preserving for which they are never asked to make a sacrifice." His view was that,

while it was desirable

to remove imperial troops gradually and throw the responsibility of self-defence largely upon Canada, "the movement in

that direction should be

made with due caution." "The present"--he was writing to the secretary of state in 1848 when Canadian affairs

were still in an

unsatisfactory state--"is not a favourable moment for experiments. British statesmen, even secretaries of state, have

got into the habit

lately of talking of the maintenance of the connection between Great Britain and Canada with so much indifference, that

a change of system in

respect to military defence incautiously carried out, might be presumed by many to argue, on the part of the

mother country, a

disposition to prepare the way for separation." And he added three years later:

"If these communities are only

truly attached to the

connection and satisfied of its permanence (and as respects the latter point, opinions here will be much

influenced by the tone

of statesmen at home), elements of self-defence, not moral elements only, but material elements

likewise, will spring up

within them spontaneously as the product of movements from within, not of pressure from

without. Two millions of

people in a northern latitude can do a good deal in the way of helping themselves, when their

hearts are in the right

place."

Before two decades of years had passed away, the

foresight of these

suggestions was clearly shown. Canada had become a part of a British North American confederation, and with the

development of its material resources, the growth of a national spirit of

self-reliance, the new

Dominion, thus formed, was able to relieve the parent state of the expenses of self-defence, and come to her aid many

years later when her

interests were threatened in South Africa. If Canada has been able to do all this, it has been owing to the growth of

that spirit of

self-reliance--of that principle of self-government--which Lord Elgin did his utmost to encourage. We can then well

understand that Lord

Elgin, in 1855, should have contemplated with some apprehension the prospect of largely increasing the Canadian

garrisons at a time when Canadians were learning steadily and surely to

cultivate the national

habit of depending upon their own internal resources in their working out of the political institutions given them by

England after years of

agitation, and even suffering, as the history of the country until 1840 so clearly shows. It is also easy to

understand that Lord Elgin should have regarded the scheme in contemplation

as likely to create a

feeling of doubt and suspicion as to the motives of the imperial government in the minds of the people of the

United States. He

recalled naturally his important visit to that country, where he had given eloquent expression, as the representative

of the British Crown, to

his sanguine hopes for the continuous amity of peoples allied to each other by so many ties of kindred and

interest, and had also

succeeded after infinite labour in negotiating a treaty so well calculated to create a common sympathy between

Canada and the republic,

and stimulate that friendly intercourse which would dispel many national prejudices and antagonisms which had

unhappily arisen between

these communities in the past. The people of the United States might well, he felt, see some inconsistency

between such friendly

sentiments and the sending of large military reinforcements to Canada.

In the spring of 1857 Lord

Elgin accepted from Lord Palmerston a delicate mission to China at a very critical time

when the affair of the

lorcha "Arrow" had led to a serious rupture between that country and Great Britain. According to the British

statement of the case, in October, 1856, the Chinese authorities at Canton

seized the lorcha

although it was registered as a British vessel, tore down the British flag from its masthead, and carried away the crew

as prisoners. On the

other hand the Chinese claimed that they had arrested the crew, who were subjects of the emperor, as pirates, that the

British ownership had

lapsed some time previously, and that there was no flag flying on the vessel at the time of its seizure. The British

representatives in China

gave no credence to these explanations but demanded not only a prompt apology but also the fulfilment of "long

evaded treaty

obligations." When these peremptory demands were not at once complied with, the British proceeded in a very summary

manner to blow up

Chinese forts, and commit other acts of war, although the Chinese only offered a passive resistance to these efforts to

bring them to terms of

abject submission. Lord Palmerston's government was condemned in the House of Commons for the violent measures

which had been taken in

China, but he refused to submit to a vote made up, as he satirically described it, "of a fortuitous concourse of

atoms," and appealed to

the country, which sustained him. While Lord Elgin was on his way to China, he heard the news of the great mutiny in

India, and received a

letter from Lord Canning, then governor-general, imploring him to send some assistance from the troops under his

direction. He at once sent "instructions far and wide to turn the transports

back and give Canning

the benefit of the troops for the moment." It is impossible, say his contemporaries, to exaggerate the

importance of the aid which he so promptly gave at the most critical time in

the Indian situation.

"Tell Lord Elgin," wrote Sir William Peel, the commander of the famous Naval Brigade at a later time, "that it was the

Chinese expedition which

relieved Lucknow, relieved Cawnpore, and fought the battle of December 6th." But this patriotic decision delayed

somewhat the execution

of Lord Elgin's mission to China. It was nearly four months after he had despatched the first Chinese

contingent to the relief of the Indian authorities, that another body of

troops arrived in China

and he was able to proceed vigorously to execute the objects of his visit to the East. After a good deal of fighting

and bullying, Chinese

commissioners were induced in the summer of 1859 to consent to sign the Treaty of Tientsin, which gave permission to

the Queen of Great

Britain to appoint, if she should see fit, an ambassador who might reside permanently at Pekin, or visit it

occasionally according to the pleasure of the British government, guaranteed

protection to

Protestants and Roman Catholics alike, allowed British subjects to travel to all parts of the empire, under passports

signed by British

consuls, established favourable conditions for the protection of trade by foreigners, and indemnified the British

government for the losses that had been sustained at Canton and for the

expenses of the war.

Lord Elgin then paid an official visit to Japan,

where he was well

received and succeeded in negotiating the Treaty of Yeddo, which was a decided advance on all previous arrangements with

that country, and

prepared the way for larger relations between it and England. On his return to bring the new treaty to a conclusion, he

found that the

commissioners who had gone to obtain their emperor's full consent to its provisions, seemed disposed to call into

question some of the

privileges which had been already conceded, and he was consequently forced to assume that peremptory tone which

experience of the Chinese has shown can alone bring them to understand the

full measure of their

responsibilities in negotiations with a European power. However, he believed he had brought his mission to a

successful close, and

returned to England in the spring of 1859.

How little interest was taken

in those days in Canadian affairs by British public men and people, is shown by some

comments of Mr. Waldron

on the incidents which signalized Lord Elgin's return from China. "When he returned in 1854 from the

government of Canada," this writer naively admits, "there were comparatively

few persons in England

who knew anything of the great work he had done in the colony. But his brilliant successes in the East attracted

public interest and gave

currency to his reputation." He accepted the position of postmaster-general in the administration just

formed by Lord

Palmerston, and was elected Lord Rector of Glasgow; but he had hardly commenced to study the details of his office, and

enjoy the amenities of

the social life of Great Britain, when he was again called upon by the government to proceed to the East, where the

situation was once more

very critical. The duplicity of the Chinese in their dealings with foreigners had soon shown itself after his

departure from China,

and he was instructed to go back as Ambassador Extraordinary to that country, where a serious rupture had occurred

between the English and

Chinese while an expedition of the former was on its way to Pekin to obtain the formal ratification of the Treaty of

Tientsin. The French

government, which had been a party to that treaty, sent forces to cooeperate with those of Great Britain in

obtaining prompt satisfaction for an attack made by the Chinese troops on the

British at the Peilo,

the due ratification of the Treaty of Tientsin, and payment of an indemnity to the allies for the expenses of their

military operations.

The punishment which the Chinese received for

their bad faith and

treachery was very complete. Yuen-ming-yuen, the emperor's summer palace, one of the glories of the empire, was

levelled to the ground

as a just retribution for treacherous and criminal acts committed by the creatures of the emperor at the very moment it

was believed that the

negotiations were peacefully terminated. Five days after the burning of the palace, the treaty was fully

ratified between the

emperor's brother and Lord Elgin, and full satisfaction obtained from the imperial authorities at Pekin for their

shameless disregard of

their solemn engagements. The manner in which the British ambassador discharged the onerous duties of his mission, met

with the warm approval

of Her Majesty's government and when he was once more in England he was offered by the prime minister the

governor-generalship of

India. He accepted this great office with a full sense of

the arduous

responsibilities which it entailed upon him, and said good-bye to his friends with words which showed that he had a

foreboding that he might never see them again--words which proved unhappily

to be too true. He went

to the discharge of his duties in India in that spirit of modesty which was always characteristic of him. "I

succeeded," he said, "to a great man (Lord Canning) and a great war, with a

humble task to be humbly

discharged." His task was indeed humble compared with that which had to be performed by his eminent

predecessors, notably by Earl Canning, who had established important reforms in

the land tenure, won the

confidence of the feudatories of the Crown, and reorganized the whole administration of India after the tremendous

upheaval caused by the

mutiny. Lord Elgin, on the other hand, was the first governor-general appointed directly by the Queen,

and was now subject to

the authority of the secretary of state for India. He could consequently exercise relatively little of the

powers and

responsibilities which made previous imperial representatives so potent in the conduct of Indian affairs. Indeed he

had not been long in

India before he was forced by the Indian secretary to reverse Lord Canning's wise measure for the sale of a

fee-simple tenure with all its political as well as economic advantages. He

was able, however, to

carry out loyally the wise and equitable policy of his predecessor towards the feudatories of England with firmness

and dignity and with

good effect for the British government.[24]

In 1863 he decided on making a

tour of the northern parts of India with the object of making himself personally

acquainted with the

people and affairs of the empire under his government. It was during this tour that he held a Durbar or Royal Court at

Agra, which was

remarkable even in India for the display of barbaric wealth and the assemblage of princes of royal descent. After

reaching Simla his

peaceful administration of Indian affairs was at last disturbed by the necessity--one quite clear to him--of repressing

an outburst of certain

Nahabee fanatics who dwelt in the upper valley of the Indus. He came to the conclusion that "the interests both

of prudence and humanity

would be best consulted by levelling a speedy and decisive blow at this embryo conspiracy." Having

accordingly made the requisite arrangements for putting down promptly the trouble

on the frontier and

preventing the combination of the Mahommedan inhabitants in those regions against the government, he left Simla and

traversed the upper

valleys of the Beas, the Ravee, and the Chenali with the object of inspecting the tea plantations of that district

and making inquiries as

to the possibility of trade with Ladak and China. Eventually, after a wearisome journey through a most picturesque

region, he reached

Dhurmsala--"the place of piety"--in the Kangra valley, where appeared the unmistakable symptoms of the fatal malady

which soon caused his

death. The closing scenes in the life of the statesman

have been described in

pathetic terms by his brother-in-law, Dean Stanley.[25] The intelligence that the illness was mortal "was

received with a calmness and fortitude which never deserted him" through

all the scenes which

followed. He displayed "in equal degrees, and with the most unvarying constancy, two of the grandest elements of human

character--unselfish

resignation of himself to the will of God, and thoughtful consideration down to the smallest particulars,

for the interests and

feelings of others, both public and private." When at his own request, Lady Elgin chose a spot for his grave in the

little cemetery which

stands on the bluff above the house where he died, "he gently expressed pleasure when told of the quiet and

beautiful aspect of the

place chosen, with the glorious view of the snowy range towering above, and the wide prospect of hill and plain

below." During this

fatal illness he had the consolation of the constant presence of his loving wife, whose courageous spirit enabled her

to overcome the weakness

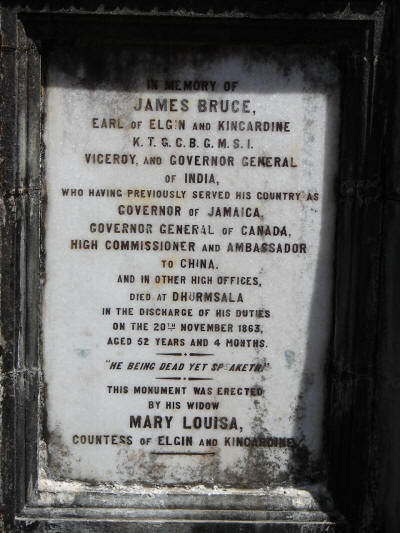

of a delicate constitution. He died on November 20th, 1863, and was buried on the following day beneath the

snow-clad Himalayas.[26]

If at any time a Canadian

should venture to this quiet station in the Kangra valley, let his first thought be, not of

the sublimity of the

mountains which rise far away, but of the grave where rest the remains of a statesman whose pure unselfishness, whose

fidelity to duty, whose

tender and sympathetic nature, whose love of truth and justice, whose compassion for the weak, whose trust in God and

the teachings of Christ,

are human qualities more worthy of the admiration of us all than the grandest attributes of nature.

None of the distinguished

Canadian statesmen who were members of Lord Elgin's several administrations from 1847 until

1854, or were then

conspicuous in parliamentary life, now remain to tell us the story of those eventful years. Mr. Baldwin died five years

before, and Sir Louis

Hypolite LaFontaine three months after the decease of the governor-general of India, and in the roll of

their Canadian

contemporaries there are none who have left a fairer record. Mr. Hincks retired from the legislature of Canada in

1855, when he accepted

the office of governor-in-chief of Barbadoes and the Windward Islands from Sir William Molesworth, colonial

secretary in Lord

Palmerston's government, and for years an eminent advocate of a liberal colonial policy. This appointment was well

received throughout

British North America by Mr. Hincks's friends as well as political opponents, who recognized the many merits of this

able politician and

administrator. It was considered, according to the London Times, as "the inauguration of a totally different system of

policy from that which

has been hitherto pursued with regard to our colonies." "It gave some evidence," continued the same paper, "that

the more distinguished

among our fellow-subjects in the colonies may feel that the path of imperial ambition is henceforth open to them." It

was a direct answer to

the appeal which had been so eloquently made on more than one occasion by the Honourable Joseph Howe[27] of Nova

Scotia, to extend

imperial honours and offices to distinguished colonists, and not reserve them, as was too often the case, for

Englishmen of inferior

merit. "This elevation of Mr. Hincks to a governorship," said the Montreal Pilot at the time, "is the most

practicable comment which can possibly be offered upon the solemn and

sorrowful complaints of

Mr. Howe, anent the neglect with which the colonists are treated by the imperial government. So sudden, complete and

noble a disclaimer on

the part of Her Majesty's minister for the colonies must have startled the delegate from Nova Scotia, and we trust that

his turn may not be far

distant." Fifteen years later, Mr. Howe himself became a lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia, and an inmate

of the very government

house to which he was not admitted in the stormy days when he was fighting the battle of responsible

government against Lord

Falkland. Mr. Hincks was subsequently appointed governor of

British Guiana, and at

the same time received a Commandership of the Bath as a mark of "Her Majesty's approval honourably won by very

valuable and continued

service in several colonies of the empire." He retired from the imperial service with a pension in 1869, when his

name was included in the

first list of knights which was submitted to the Queen on the extension of the Order of St. Michael and St.

George for the express

purpose of giving adequate recognition to those persons in the colonies who had rendered distinguished service to

the Crown and empire.

During his Canadian administration Lord Elgin had impressed upon the colonial secretary that it was "very

desirable that the

prerogative of the Crown, as the fountain of honour, should be employed, in so far as this can properly be done,

as a means of attaching

the outlying parts of the empire to the throne." Two principles ought, he thought, "as a general rule

to be attended to in the

distribution of imperial honours among colonists." Firstly they should appear "to emanate directly from the Crown,

on the advice, if you

will, of the governors and imperial ministers, but not on the recommendation of the local executive." Secondly,

they "should be

conferred, as much as possible, on the eminent persons who are no longer engaged actively in political life." The

first principle has,

generally speaking, guided the action of the Crown in the distribution of honours to colonists, though the governors may

receive suggestions from

and also consult their prime ministers when the necessity arises. These honours, too, are no longer conferred only

on men actively engaged

in public life, but on others eminent in science, education, literature, and other vocations of life.[28]

In 1870 Sir Francis Hincks

returned to Canadian public life as finance minister in Sir John Macdonald's government, and

held the office until

1873, when he retired altogether from politics. Until the last hours of his life he continued to show that acuteness of

intellect, that aptitude

for public business, that knowledge of finance and commerce, which made him so influential in public affairs.

During his public career

in Canada previous to 1855, he was the subject of bitter attacks for his political acts, but nowadays

impartial history can

admit that, despite his tendency to commit the province to heavy expenditures, his energy, enterprise and financial

ability did good service

to the country at large. He was also attacked as having used his public position to promote his own pecuniary

interests, but he

courted and obtained inquiry into the most serious of such accusations, and although there appears to have

been some carelessness

in his connection with various speculations, and at times an absence of an adequate sense of his responsibility as a

public man, there is no

evidence that he was ever personally corrupt or dishonest. He devoted the close of his life to the writing of

his "Reminiscences," and

of several essays on questions which were great public issues when he was so prominent in Canadian politics, and

although none of his

most ardent admirers can praise them as literary efforts of a high order, yet they have an interest so far as they

give us some insight

into disputed points of Canada's political history. He died in 1885 of the dreadful disease small-pox in the city of

Montreal, and the

veteran statesman was carried to the grave without those funeral honours which were due to one who had filled with

distinction so many

important positions in the service of Canada and the Crown. All his contemporaries when he was prime minister also lie

in the grave and have

found at last that rest which was not theirs in the busy, passionate years of their public life. Sir Allan

MacNab, who was a

spendthrift to the very last, lies in a quiet spot beneath the shades of the oaks and elms which adorn the lovely park

of Dundurn in Hamilton,

whose people have long since forgotten his weaknesses as a man, and now only recall his love for the

beautiful city with whose interests he was so long identified, and his

eminent services to Crown and state. George Brown, Hincks's inveterate

opponent, continued for

years after the formation of the first Liberal-Conservative administration, to keep the old province of Canada

in a state of political

ferment by his attacks on French Canada and her institutions until at last he succeeded in making government

practically unworkable,

and then suddenly he rose superior to the spirit of passionate partisanship and racial bitterness

which had so long

dominated him, and decided to aid his former opponents in consummating that federal union which relieved old Canada of

her political

embarrassment and sectional strife. His action at that time is his chief claim to the monument which has been raised

in his honour in the

great western city where he was for so many years a political force, and where the newspaper he established still

remains at the head of

Canadian journalism.

The greatest and ablest man among all who were

notable in Lord Elgin's

days in Canada, Sir John Alexander Macdonald--the greatest not simply as a Canadian politician but as one of the

builders of the British

empire--lived to become one of Her Majesty's Privy Councillors of Great Britain, a Grand Cross of the Bath, and

prime minister for

twenty-one years of a Canadian confederation which stretches for 3,500 miles from the Atlantic to the Pacific ocean. When

death at last forced him

from the great position he had so long occupied with distinction to himself and advantage to Canada,

the esteem and affection

in which he was held by the people, whom he had so long served during a continuous public career of half a

century, were shown by

the erection of stately monuments in five of the principal cities of the Dominion--an honour never before paid to a

colonial statesman. The

statues of Sir John Macdonald and Sir Georges Cartier--statues conceived and executed by the genius of a French

Canadian artist--stand

on either side of the noble parliament building where these statesmen were for years the most

conspicuous figures; and as Canadians of the present generation survey their

bronze effigies, let

them not fail to recall those admirable qualities of statesmanship which distinguished them both--above all their

assertion of those

principles of compromise, conciliation and equal rights which have served to unite the two races in critical times

when the tide of racial

and sectional passion and political demagogism has rushed in a mad torrent against the walls of the national

structure which

Canadians have been so steadily and successfully building for so many years on the continent of North America. |