Fort Vancouver on American soil—Chief Factor Douglas chooses a new

site—Young McLoughlin killed—Liquor selling prohibited— Dealing with the

Songhies—A Jesuit father—Fort Victoria— Finlayson's skill—Chinook

jargon—The brothers Ermatinger—A fur-trading Junius—"Fifty-four, forty, or

fight"—Oregon Treaty —Hudson's Bay Company indemnified—The waggon road— A

colony established—First governor—Gold fever—British Columbia—Fort

Simpson—Hudson's Bay Company in the interior—The forts—A group of

worthies—Service to Britain— The coast become Canadian.

The Columbia River grew to be a source of wealth to

the Hudson's Bay Company. Its farming facilities were great, and its

products afforded a large store for supplying the Russian settlements of

Alaska. But as on the Rod River, so here the influx of agricultural

settlers sounded a note of warning to the fur trader that his day was soon

to pas3 away. With the purpose of securing the northern trade, Fort

Langley had been built on the Eraser River. The arrival of Sir Georgo

Simpson on the coast on his journey round the world was the occasion of

the Company taking a most important stop in order to hold the trade of

Alaska.

In the year

following Sir George's visit, Chief Factor Douglas crossed Puget Sound and

examined the southern extremity of Vancouver Island as to its suitability

for the erection of a new fort to take the place in due time of Fort

Vancouver. Douglas found an excellent site, close beside the splendid

harbour of Esquimalt, and reported to the assembled council of chief

factors and traders at Fort Vancouver that the advantages afforded by the

site, especially that of its contiguity to the sea, would place the new

fort, for all their purposes, in a much better position than Fort

Vancouver. The enterprise was accordingly determined on for the next

season.

A tragic incident took place at this time on the

Pacific Coast, which tended to make the policy of expansion adopted appear

to be a wise and reasonable one. This was the violent death of a young

trader, the son of Chief Trader McLoughlin, at Fort Taku on the coast of

Alaska, in the territory leased from the Russians by the Hudson's Bay

Company. The murder was the result of a drunken dispute among the Indians,

in which, accidentally, young McLoughlin had been shot.

Sir George Simpson had just returned to the fort from

his visit to the Sandwich Islands, and was startled at seeing the Russian

and British ships, with flags at half-mast, on account of the young

trader's death. The Indians, on the arrival of the Governor, expressed the

greatest penitence, but the stern Lycurgus could not be appeased, and this

calamity, along with one of a similar kind, which had shortly before

occurred on the Stikine River, led Sir George Simpson and the Russian

Governor Etholin to come to an agreement to discontinue at once the sale

of spirituous liquor in trading with the Indians. The Indians for a time

resorted to every device, such as withholding their furs unless liquor was

given them, but the traders were unyielding, and the trade on the coast

became safer and more profitable on account of the disuse of strong drink.

The decision to build a new fort having been reached

in the next spring, the moving spirit of the trade on the coast, James

Douglas, with fifteen men, fully supplied with food and necessary

implements, crossed in the Beaver from Nisqually, like another Eneas

leaving his untenable city behind to build a new Troy elsewhere. On the

next day, March 13th, the vessel came to anchor opposite the new site.

A graphic writer has given us the description of the

beautiful spot: "The view landwards was enchanting. Before them lay a vast

body of land, upon which no white man then stood. Not a human habitation

was in sight; not a beast, scarcely a bird. Even the gentle murmur of the

voiceless wood was drowned by the gentle beating of the surf upon the

shore. There was something specially charming, bewitching in the place.

Though wholly natural it did not seem so. It was not at all like pure art,

but it was as though nature and art had combined to map out and make one

of the most pleasing prospects in the world."

The visitor looking at the City of Victoria in

British Columbia to-day will say that the description is in no way

overdrawn. Not only is the site one of the most charming on the earth, but

as the spectator turns about he is entranced with the view on the

mainland, of Mount Olympia, so named by that doughty captain, John Meares,

more than fifty years before the founding of this fort.

The place had been already chosen for a village and

fortification by the resident tribe, the Songhies, and went by the Indian

name of Camosun. The Indian village was a mile-distant from the entrance

to the harbour. When the Beaver came to anchor, a gun was fired, which

caused a commotion among the natives, who were afraid to draw near the

intruding vessel. Next morning, however, the sea was alive with canoes of

the Songhies.

The trader immediately landed, chose the site for his

post, and found at a short distance tall and straight cedar-trees, which

afforded material for the stockades of the fort. Douglas explained to the

Indians the purpose of his coming, and held up to them bright visisons of

the beautiful things he would bring them to exchange for their furs. He

also employed the Indians in obtaining for him the cedar posts needed for

his palisades.

The trader showed his usual tact in employing a most

potent means of gaining an influence over the savages by bringing the

Jesuit Father Balduc, who had been upon the island before and was known to

the natives. Gathering the three tribes of the south of the island, the

Songhies, Clallams, and Cowichins, into a great rustic chapel which had

been prepared, Father Balduc hold an impressive religious service, and

shortly after visited a settlement of the Skagits, a thousand strong, and

there too, in a building erected for public worship, performed the

important religious rites of his Church before the wondering savages.

It was the intention of the Hudson's Bay Company to

make the new fort at Camosun, which they first called Fort Albert, and

afterwards Fort Victoria—the name now borne by the city, the chief trading

depot on the coast.

As soon as the buildings were well under way, Chief

Factor Douglas sailed northward along the coast to re-arrange the trade.

Fort Simpson, which was on the mainland, some fifteen degrees north of the

new fort and situated between the Portland Canal and the mouth of the

Skeena River, was to be retained as necessary for the Alaska trade, but

the promising officer, Roderick Finlayson, a young Scotchman, who had

shown his skill and honesty in the northern post, was removed from it and

given an important place in the new establishment. Living a useful and

blameless life, he was allowed to see the new fort become before his death

a considerable city. Charles Ross, the master of Fort McLoughlin, being

senior to Finlayson, was for the time being placed in charge of the new

venture. The three minor forts, Taku, Stikine, and McLoughlin, were now

closed, and the policy of consolidation led to Fort Victoria at once

rising into importance.

On the return of the chief factor from his northern

expedition, with all the employes and stores from the deserted posts, the

work at Fort Victoria went on apace. The energetic master had now at his

disposal fifty good men, and while some were engaged at the

buildings—either storehouses or dwellings—others built the defences. Two

bastions of solid block work were erected, thirty feet high, and these

were connected by palisades or stockades of posts twenty feet high, driven

into the earth side by side. The natives encamped alongside the new work,

looked on with interest, but as they had not their wives and children with

them, the traders viewed them with suspicion. On account of the

watchfulness of the builders, the Indians, beyond a few acts of petty

theft, did not interfere with the newcomers in their enterprise.

Three months saw the main features of the fort

completed. On entering the western gate of the fort, to the right was to

be seen a cottage-shaped building, the post office, then the smithy;

further along the walls were the large storehouse, carpenter's shop, men's

dormitory, and the boarding-house for the raw recruits. Along the east

wall wore the chapel, chaplain's house, then the officers' dining-room,

and cook-house from other Indian languages, almost a hundred were French,

and less than seventy English, while several were doubtful. The then

leading elements among the traders were known in the Jargon as

respectively, Pasai-ooks, French, a corruption of Francais; King

Chautchman (King George man), English ; and Boston, American. The

following will show the origin and meaning of a few words, showing changes

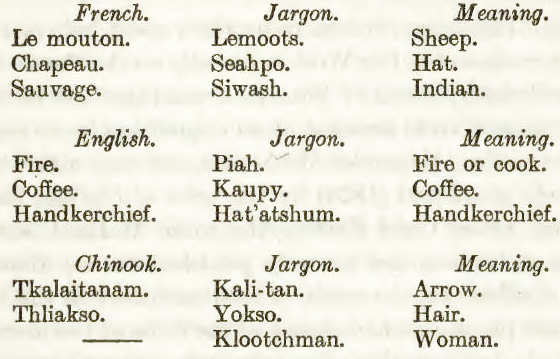

made in consonants which the Indians cannot pronounce.

Songs, hymns, sermons, and translations of portions

of the Bible are made in the jargon, and used by missionaries and

teachers. Several dictionaries of the dialect have been published.

Among the out-standing men who were contemporaries

upon the Pacific Coast of Finlayson were the two brothers Ermatinger.

Already it has been stated that they were nephews of the famous old trader

of Sault Ste. Marie. Their father had preferred England to Canada, and had

gone thither. His two sons, Edward and Francis, were, as early as 1818,

apprenticed by their father to the Hudson's Bay Company and sent on the

Company's ship to Rupert's Land, by way of York Factory. Edward, whose

autobiographical sketch, hitherto unpublished, lies before us, tells us

that he spent ten years in the fur trade, being engaged at York Factory,

Oxford House, Red River, and on the Columbia River. Desirous of returning

to the service after he had gone back to Canada, he had received an

appointment to Rupert's Land again from Governor Simpson. This was

cancelled by the Governor on account of a grievous quarrel with old

Charles, the young trader's uncle, on a sea voyage with the Governor to

Britain. For many years, however, Edward Ermatinger lived at St. Thomas,

Ontario, where his son, the respected Judge Ermatinger, still resides. The

old gentleman became a great authority on Hudson's Bay affairs, and

received many letters from the traders, especially, it would seem, from

those who had grievances against the Company or against its strong-willed

Governor.

Francis Ermatinger, the other brother, spent between

thirty and forty years in the Far West, especially on the Pacific Coast.

An unpublished journal of Francis Ermatinger lies before us. It is a clear

and vivid account of an expedition to revenge the death of a trader,

Alexander Mackenzie, and four men who had been basely murdered (1828) by

the tribe of Clallam Indians. The party, under Chief Factor Alexander

McLeod, attacked one band of Indians and severely punished them; then from

the ship Cadboro on the coast, a bombardment of the Indian village took

place, in which many of the tribe of the murderers were killed, but

whether the criminals suffered was never known.

That Francis Ermatinger was one of the most hardy,

determined, and capable of the traders is shown by a remarkable Journey

made by him, under orders from Sir George Simpson on his famous journey

round the world. Ermatinger had left Fort Vancouver in charge of a party

of trappers to visit the interior of California. Sir George, having heard

of him in the upper waters of one of the rivers of the coast, ordered him

to meet him at Monterey. This Ermatinger undertook to do, and after a

terrific journey, crossing snowy chains of mountains, fierce torrents in a

country full of pitfalls, reached the imperious Governor. Ermatinger had

assumed the disguise of a Spanish caballero, and was recognized by his

superior officer with some difficulty. Ermatinger wrote numerous letters

to his brothers in Canada, which contained details of the hard but

exciting life he was leading.

Most unique and peculiar of all the traders on the

Pacific Coast was John Tod, who first appeared as a trader in the Selkirk

settlement and wrote a number of the Hargrave letters. In 1823 he was sent

by Governor Simpson, it is said, to New Caledonia as to the penal

settlement of the fur traders, but the young Scotchman cheerfully accepted

his appointment. He became the most noted letter-writer of the Pacific

Coast, indeed he might be called the prince of controversialists among the

traders. There lies before the writer a bundle of long letters written

over a number of years by Tod to Edward Ermatinger. Tod, probably for the

sake of argument, advocated loose views as to the validity of the

Scriptures, disbelief of many of the cardinal Christian doctrines, and in

general claimed the greatest latitude of belief. It is very interesting to

6ee how the solemn-minded and orthodox Ermatinger strives to load him into

the true way. Tod certainly had little effect upon his faithful

correspondent, and shows the greatest regard for his admonitions.

The time of Sir George Simpson's visit to the coast

on his journey round the world was one of much agitation as to the

boundary line between the British and United States possessions on the

Pacific Coast. By the treaty of 1825 Russia and Britain had come to an

agreement that the Russian strip along the coast should reach southward

only to 54 deg. 40' N. lat. The United States mentioned its claim to the

coast as far north as the Russian boundary. However preposterous it may

seem, yet it was maintained by the advocates of the Munroe doctrine that

Great Britain had no share of the coast at all. The urgency of the

American claim became so great that the popular mind seemed disposed to

favour contesting this claim with arms. Thus originated the famous saying,

"Fifty-four, forty, or fight." The Hudson's Bay Company was closely

associated with the dispute, the more that Fort Vancouver on the Columbia

River might be south of the boundary line, though their action of building

Fort Victoria was shown to be a wise and timely step. At length in 1846

the treaty between Great Britain and the United States was made and the

boundary line established. The Oregon Treaty, known in some quarters as

the Ashburton Treaty, provided that the 49th parallel of latitude should

on the mainland be the boundary, thus handing over Fort Vancouver, Walla

Walla, Colville, Nisqually, and Okanagan to the United States, and taking

them from their rightful owners, the Hudson's Bay Company. Article two of

the great treaty, however, stated that the Company should enjoy free

navigation of the Columbia River, while the third article provided that

the possessory rights of the Hudson's Bay Company and all other British

subjects on the south side of the boundary line should be respected.

The decision in regard to the boundary led to changes

in the Hudson's Bay Company establishments. Dr. McLoughlin, having lost

the confidence of the Company, threw in his lot with his United States

homo, and retired in the year of the treaty to Oregon City, where he died

a few years after. His name is remembered as that of an impulsive,

good-hearted, somewhat rash, but always well-meaning man.

Though Fort Victoria became the depot for the coast

of the trade of the Company, Fort Vancouver, with a reduced staff, was

maintained for a number of years by the Company. While under charge of

Chief Trader Wark, a part of the fields belonging to the Company at Fort

Vancouver were in a most highhanded manner seized by the United States for

military purposes. The senior officer, Mr. Grahame, on his return from an

absence, protested against the invasion. In June, 1860, however, the

Hudson's Bay Company withdrew from the Columbia. The great herd of wild

cattle which had grown up on the Columbia were disposed of by the Company

to a merchant of Oregon. The Company thus retired to the British side of

the boundary line during the three years closing with 1860.

Steps were taken by the Hudson's Bay Company to

obtain compensation from the United States authorities. A long and

wearisome investigation took place; witnesses were called and great

diversity of opinion prevailed as to the value of the interest of the

Company in its forts. The Hudson's Bay Company claimed indemnity amounting

to the sum of 2,000,000 dols. Witnesses for the United States gave

one-tenth of that amount as a fair value. Compensation of a moderate kind

was at length made to the Company by the United States.

On its withdrawal from Oregon the Hudson's Bay

Company decided on opening up communication with the interior of the

mainland up the Fraser River. This was a task of no small magnitude, on

account of the rugged and forbidding banks of

this great river. A. Caulfield Anderson, an officer

who had been in the Company's service for some fourteen years before the

date of the Oregon Treaty and was in charge of a post on the Fraser River,

was given the duty of finding the road to the interior. He was successful

in tracing a road from Fort Langley to Kamloops. The Indians offered

opposition to Anderson, but he succeeded in spite of all hindrances, and

though other routes were sought for and suggested, yet Anderson's road by

way of the present town of Hope and Lake Nicola to Kamloops afterwards

became one great waggon road to the interior. No sooner had the boundary

line been fixed than agitation arose to prepare the territory north of the

line for a possible influx of agriculturists or miners and also to

maintain the coast true to British connection. The Hudson's Bay Company

applied to the British Government for a grant of Vancouver Island, which

they held under a lease good for twelve years more. Mr. Gladstone opposed

the application, but considering it the best thing to be done in the

circumstances, the Government made the grant (1847) to the Company under

certain conditions. The Company agreed to colonize the island, to sell the

lands at moderate rates to settlers, and to apply nine-tenths of the

receipts toward public improvements. The Company entered heartily into the

project, issued a prospectus for settlers, and hoped in five years to have

a considerable colony established on the Island.

Steps were taken by the British Government to

organize the new colony. The head of the Government applied to the

Governor of the Company to name a Governor. Chief Factor Douglas was

suggested, but probably thinking an independent man would be more

suitable, the Government gave the appointment to a man of respectability,

Richard Blanshard, in the end of 1849.

The new Governor arrived, but no preparations had

been made for his reception. No salary was provided for his maintenance,

and the attitude of the Hudson's Bay Company officially at Fort Victoria

was decidedly lacking in heartiness. Governor Blanshard's position was

nothing more than an empty show. He issued orders and proclamations which

were disregarded. He visited Fort Rupert, which had been founded by the

Company on the north-east angle of the island, and there held an

investigation of a murder of three sailors by the Newitty Indians.

Governor Blanshard spent much of his time writing pessimistic reports of

the country to Britain, and after a residence of a year and a half

returned to England, thoroughly soured on account of his treatment by the

officers of the Company.

The colonization of Vancouver Island proved very

slow. A company of miners for Nanaimo, and another of farmers for Sooke,

near Victoria, came, but during Governor Blanshard's rule only one

bona-fide sale of land was made, and five years after the cession to the

Company there were less than five hundred colonists. Chief Factor Douglas

succeeded to the governorship and threw his accustomed energy into his

administration. The cry of monopoly, ever a popular one, was raised, and

inasmuch as the colony was not increasing sufficiently to satisfy the

Imperial Government, the great Committee of the House of Commons of 1857

was appointed to examine the whole relation of the Company to Rupert's

Land and the Indian territories. The result of the inquiry was that it was

decided to relieve the Hudson's Bay Company of the charge of Vancouver

Island at the time of expiry of their lease. The Hudson's Bay Company thus

withdrew on the Pacific Coast to the position of a private trading

company, though Sir James Douglas, who was knighted in 1863, continued

Governor of the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island, with the added

responsibility of the territory on the mainland.

At this juncture the gold discovery in the mainland

called much attention to the country. Thousands of miners rushed at once

to the British possessions on the Pacific Coast. Fort Victoria, from being

a lonely traders' post, grew as if by magic into a city. Thousands of

miners betook themselves to the Fraser River, and sought the inland

gold-fields. All this compelled a more complete organization than the mere

oversight of the mainland by Governor Douglas in his capacity as head of

the fur trade. Accordingly the British Government determined to relieve

the Hudson's Bay Company of responsibility for the mainland, which they

hold under a licence soon to expire, and to erect Now Caledonia and the

Indian territories of the coast into a separate Crown Colony under the

name of British Columbia. In Lord Lytton's dispatches to Governor Douglas,

to whom the governorship of both of the colonies of Vancouver Island and

British Columbia was offered, the condition is plainly stated that he

would be required to sever his connection with the Hudson's Bay Company

and the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, and to be independent of all

local interests. Here we leave Sir James Douglas immersed in his public

duties of governing the two colonies, which in time became one province

under the name of British Columbia, thus giving up the guidance of the

fur-trading stations for whose up-building he had striven for fifty years.

The posts of the Hudson's Bay Company on the Pacific

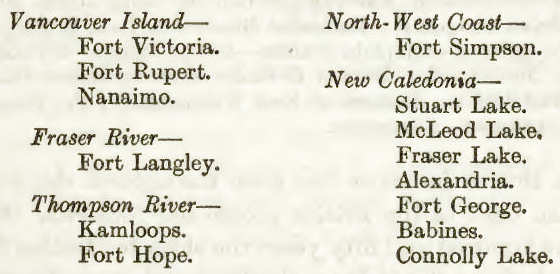

Coast in 1857 were:—

|