The bleak shores

unprogressive—Now as

at the

beginning—York

Factory—Description

of Ballantyne—The

weather—Summer comes

with a rush—Picking

up subsistence—The

Indian trade—

Inhospitable

Labrador—Establishment

of Ungava Bay—McLean

at Fort Chimo—Herds

of cariboo—Eskimo

crafts—"Shadowy

Tartarus"—The king's

domains—Mingan—Mackenzie—The

Gulf settlements—The

Moravians—Their four

missions—Rigolette,

the chief trading

post—A school for

developing

character—Chief

Factor Donald A.

Smith—Journeys along

the coast—A barren

shore.

Life on the shores

of Hudson Bay is as

unchangeable as the

shores and scenery

of the coast are

monotonous. The

swampy, treeless

flats that surround

the Bay simply

change from the

frozen, snow-clad

expanse which

stretches as far as

the eye can see in

winter, to the

summer green of the

unending grey

willows and stunted

shrubs that cover

the swampy shores.

For a few open

months the green

prevails, and then

nature for eight

months assumes her

winding sheet of icy

snow.

For two hundred and

fifty years life has

been as unvarying on

these wastes as

travellers tell us

are the manners and

customs of living of

the Bedouins on

their rocky Araby.

No log shanties give

way in a generation

to the settler's

house, and then to

the comfortable,

well-built stone or

brick dwelling,

which the fertile

parts of America so

readily permit. The

accounts of McLean,

Rae, Ryerson, and

Ballantyne of the

middle of the

nineteenth century

are precisely those

of Robson, Ellis, or

Hearne of the

eighteenth century,

or indeed

practically those of

the early years of

the Company in the

seventeenth century.

The ships sail from

Gravesend on the

Thames with the same

ceremonies, with the

visit and dinner of

the committee of the

directors, the

"great guns," as the

sailors call them,

as they have done

for two centuries

and a quarter, from

the days of

Zachariah Gillam and

Pierre Esprit

Radisson. No more

settlement is now

seen on Hudson Bay

than in the early

time, unless it be

in the dwellings of

the Christianized

and civilized swampy

Crees and in the

mission houses

around which the

Indians have

gathered.

York Factory, up to

the middle of the

nineteenth century,

retained its

supremacy. However,

at times, Fort

Churchill, with its

well-built walls and

formidable bastions,

may have disputed

this primacy, yet

York Factory was the

depot for the

interior almost

uninterruptedly. To

it came the goods

for the northern

department, by way

in a single season

of the vessel the

Prince Rupert, the

successor of a long

line of Prince

Ruperts, from the

first one of 1680,

or of its

companions, the

Prince Albert or the

Prince of Wales. By

these, the furs from

the Far North found

their way, as at the

first, to the

Company's house in

London.

York Factory is a

large square of some

six acres, lying

along Hayes River,

and shut in by high

stockades. The

houses are all

wooden, and on

account of the

swampy soil are

raised up to escape

the water of the

spring-time floods.

At a point of

advantage, a lofty

platform was erected

to serve as a

"lookout" to watch

for the coming ship,

the great annual

event of , the

slow-passing lives

of the occupants of

the post. The

flag-staff, on

which, as is the

custom at all

Hudson's Bay Company

posts, the ensign

with the magic

letters H. B. C.

floats, speaks at

once of many an old

tradition and of

great achievements.

Ballantyne in his

lively style speaks

of his two years at

the post, and

describes the life

of a young Hudson's

Bay Company officer.

The chief factor, to

the eye of the young

clerk, represents

success achieved and

is the embodiment of

authority, which, on

account of the

isolation of the

posts and the

absence of all law,

is absolute and

unquestioned. York

Factory, being a

depot, has a

considerable staff,

chiefly young men,

who live in the

bachelors' hall.

Here dwell the

surgeon, accountant,

postmaster, half a

dozen clerks, and

others.

In winter,

Ballantyne says,

days, if not weeks,

passed without the

arrival of a

visitor, unless it

were a post from the

interior, or some

Cree trader of the

neighbourhood, or

some hungry Indian

seeking food. The

cold was the chief

feature of remark

and consideration.

At times the spirit

thermometer

indicated 65 deg.

below zero, and the

uselessness of the

mercury thermometer

was then shown by a

pot of quicksilver

being made into

bullets and

remaining solid.

Every precaution was

taken to erect

strong buildings,

which had double

windows and double

doors, and yet in

the very severe

weather, water

contained in a

vessel has been

known to freeze in a

room where a stove

red hot was doing

its best. It is

worthy of notice,

however, that even

in Arctic regions, a

week or ten days is

as long as such

severe weather

continues, and mild

intervals come

regularly.

On the Bay the

coming of spring is

looked for with

great expectation,

and when it does

come, about the

middle of May, it

sets in with a

"rush;" the sap

rises in the shrubs

and bushes, the buds

burst out, the

rivers are freed

from ice, and

indeed, so rapid and

complete is the

change, that it may

be said there are

only two

seasons—summer and

winter—in these

latitudes.

As summer progresses

the fare of dried

geese, thousands of

which are stored

away for winter use,

of dried fish and

the white ptarmigan

and wood partridge

that linger about

the bushes and are

shot for food, is

superseded by the

arrival of myriads

of ducks and geese

and the use of the

fresh fish of the

Bay. In many of the

posts the food

throughout the whole

year is entirely

flesh diet, and not

a pound of

farinaceous food is

obtainable. This

leads to an enormous

consumption of the

meat diet in order

to supply a

sufficient amount of

nourishment. An

employe will

sometimes eat two

whole geese at a

meal.

In Dr.

Rae's celebrated

expedition from Fort

Churchill, north

along the shore of

Hudson Bay, on his

search for Sir John

Franklin, the amount

of supplies taken

was entirely

inadequate for his

party for the long

period of

twenty-seven months,

being indeed only

enough for four

months' full

rations. In Rae's

instructions from

Sir George Simpson

it is said, "For the

remaining part of

your men you cannot

fail to find

subsistence,

animated as you are

and they are by a

determination to

fulfil your mission

at the cost of

danger, fatigue, and

privation. Whenever

the natives can

live, I can have no

fears with respect

to you, more

particularly as you

will have the

advantage of the

Eskimos, not merely

in your actual

supplies, but also

in the means of

recruiting and

renewing them."

The old forts still

remained in addition

to the two depot

posts, York and

Moose Factory, there

being Churchill,

Severn, Rupert's

House, Fort George,

and Albany—and the

life in then all of

the stereotyped

description which we

have pictured.

Besides the

preparation in

summer of supplies

for the long winter,

the only variety was

the arrival of

Indians with furs

from the interior.

The trade is carried

on by means of

well-known standards

called the "castor"

or "beaver." The

Indian hands his

furs over to the

trader, who sorts

them into different

lots. The value is

counted up at so

many—say

fifty—castors. The

Indian then receives

fifty small bits of

wood, and with these

proceeds to buy

guns, knives,

blankets, cloth,

beads, or trinkets,

never stopping till

his castors are all

exhausted. The

castor rarely

exceeds two

shillings in value.

While resembling in

its general features

the life on the Bay,

the conduct of the

fur trader on the

shore of Labrador

and throughout the

Labrador Peninsula

is much more trying

and laborious than

around the Bay. The

inhospitable

climate, the heavy

snows, the rocky,

dangerous shore, and

the scarcity in some

parts of animal

life, long prevented

the fur companies

from venturing upon

this forbidding

coast.

The northern part of

Labrador is

inhabited by Eskimos

; further south are

tribes of swampy

Crees. Between the

Eskimos and Indians

deadly feuds long

prevailed. The most

cruel and bloody

raids were made upon

the timid Eskimos,

as was done on the

Coppermine when

Hearne went on his

famous | expedition.

McLean states that

it was through the

publication of a

pamphlet by the

Moravian

missionaries of

Labrador, which I

declared that "the

country produced

excellent furs,"

that the Hudson's

Bay Company was led

to establish trading

posts in Northern

Labrador. The

stirring story of

"Ungava," written by

Ballantyne, gives

what is no doubt in

the main a correct

account of the

establishment of the

far northern post

called "Fort Chimo,"

on Ungava Bay.

The expedition left

Moose Factory in

1831, and after

escaping the dangers

of floating ice,

fierce storms, and

an unknown coast,

erected the fort

several miles up the

river running into

Ungava Bay. The

story recalls the

finding out, no

doubt somewhat after

the manner of the

famous boys' book,

"The Swiss Family

Robinson," the trout

and salmon of the

waters, the walrus

of the sea, and the

deer of the mountain

valleys, but the

picture is not

probably overdrawn.

The building of Fort

Chimo is plainly

described by one who

was familiar with

the exploration and

life of the fur

country; the picture

of the tremendous

snowstorm and its

overwhelming drifts

is not an unlikely

one for this coast,

which, since the day

of Cortcreal, has

been the terror of

navigators.

McLean, a somewhat

fretful and biassed

writer, though

certainly not

lacking in a clear

and lively style,

gives an account of

his being sent, in

1837, to take charge

of the district of

North Labrador for

the Company. On

leaving York Factory

in August the brig

encountered much

ice, although it

escaped the mishaps

which overtook

almost all small

vessels on the Bay.

The steep cliffs of

the island of

Akpatok, which

stands before Ungava

Bay, were very

nearly run upon in

the dark, and much

difficulty was

experienced in

ascending the

Ungava, or South

River, to Fort Chimo.

The trader's orders

from Governor

Simpson were to push

outposts into the

interior of

Labrador, to support

his men on the

resources of the

country, and to open

communication with

Esquimaux Bay, on

the Labrador coast,

and thus, by means

of the rivers, to

establish an inland

route of

intercommunication

between the two

inlets. McLean made

a most determined

attempt to establish

the desired route,

but after

innumerable

hardships to himself

and his company,

retired, after

nearly four months'

efforts, to Fort

Chimo, and sent a

message to his

superior officer

that the proposed

line of

communication was

impracticable.

McLean gives an

account of the

arrival of a herd of

three hundred

reindeer or cariboo,

and of the whole of

them being captured

in a "pound," as is

done in the case of

the buffalo. The

trader was also

visited by Eskimos

from the north side

of Hudson Strait,

who had crossed the

rough and dangerous

passage on "a raft

formed of pieces of

driftwood picked up

along the shore."

The object of their

visit was to obtain

wood for making

canoes. The trader

states that the fact

of these people

having crossed

"Hudson's Strait on

so rude and frail a

conveyance "

strongly

corroborates the

opinion that America

was originally

peopled from Asia by

way of Behring's

Strait.

It became more and

more evident,

however, that the

Ungava trade could

not be profitably

continued. Great

expense was incurred

in supplying Ungava

Bay by sea; the

country was poor and

barren, and the

pertinacity of the

Eskimos in adhering

to their sealskin

dresses made the

trade in fabrics,

which was profitable

among the Indians,

an impossibility at

Ungava. McLean

continued his

explorations and was

somewhat successful

in opening the

sought-for route by

way of the Grand

River, and,

returning to Fort

Chimo, wintered

there. Having been

promoted by Sir

George Simpson,

McLean obtained

leave to visit

Britain, and before

going received word

from the directors

of the Company that

his recommendation

to abandon Ungava

Bay had been

accepted, and that

the ship would call

at that point and

remove the people

and property to

Esquimaux Bay.

McLean, in speaking

of the weather of

Hudson Straits

during the month of

January (1842),

gives expression to

his strong dislike

by saying, "At this

period I have

neither seen, read,

nor heard of any

locality under

heaven that can

offer a more

cheerless abode to

civilized man than

Ungava."

Referring also to

the fog that so

abounds at this

point as well as at

the posts around

Hudson Bay, the

discontented trader

says: "If Pluto

should leave his own

gloomy mansion in

tene-bris Tartari,

he might take up his

abode here, and gain

or lose but little

by the exchange."

But the enterprising

fur-traders were not

to be deterred by

the iron-bound

coast, or foggy

shores, or dangerous

life of any part of

the peninsula of

Labrador. Early in

the century, while

the Hudson's Bay

Company were

penetrating

southward from the

eastern shore of

Hudson Bay, which

had by a kind of

anomaly been called

the "East Main," the

North-West Company

were occupying the

north shore of the

St. Lawrence and met

their rivals at the

head waters of the

Saguenay.

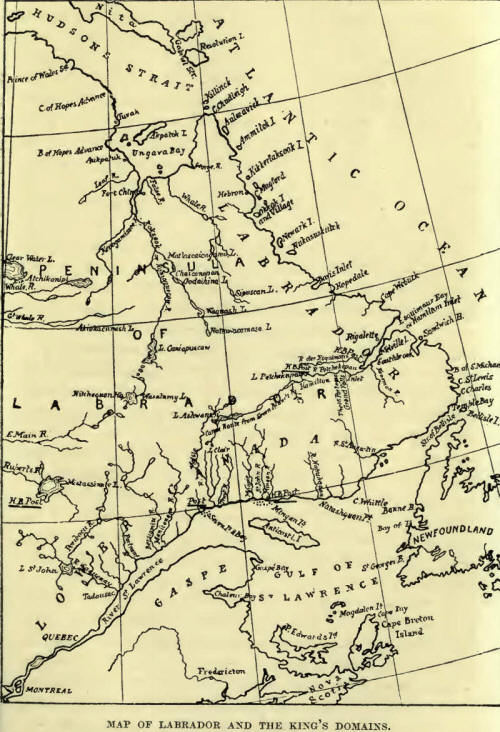

The district of

which Tadousac was

the centre had from

the earliest coming

of the French been

noted for its furs.

That district all

the way down to the

west end of the

island of Anti-costi

was known as the

"King's Domains."

The last parish was

called Murray Bay,

from General Murray,

the first British

governor of Quebec,

who had disposed of

the district, which

furnished beef and

butter for the King,

to two of his

officers, Captains

Nairn and Fraser.

The North-West

Company, in the

first decade of the

nineteenth century,

had leased this

district, which

along with the

Seigniory of Mingan

that lay still

further down the

Gulf of St.

Lawrence, was long

known as the "King's

Posts." Beyond the

Seigniory of Mingan,

a writer of the

period mentioned

states that the

Labrador coast had

been left

unappropriated, and

was a common to

which all nations at

peace with England

might resort,

unmolested, for

furs, oil, cod-fish,

and salmon.

A well-known trader,

James McKenzie,

after returning from

the Athabasca

region, made, in

1808, a canoe

journey through the

domains of the King,

and left a journal,

with his description

of the rocky country

and its inhabitants.

He pictures strongly

the one-eyed chief

of Mingan and Father

Labrosse, the Nestor

for twenty-five

years of the King's

posts, who was

priest, doctor, and

poet for the region.

McKenzie's voyage

chiefly inclined him

to speculate as to

the origin and

religion of the

natives, while his

description of the

inland Indians and

their social life is

interesting. His

account of the

manners and customs

of the Montagners or

Shore Indians was

more detailed than

that of the

Nascapees, or

Indians of the

interior, and he

supplies us with an

extensive vocabulary

of their language.

McKenzie gives a

good description of

the Saguenay River,

of Chicoutimi, and

Lake St. John, and

of the ruins of a

Jesuit establishment

which had flourished

during the French

regime. Whilst the

bell and many

implements had been

dug up from the

scene of desolation,

the plum and apple

trees of their

garden were found

bearing fruit. From

the poor neglected

fort of

Assuapmousoin

McKenzie returned,

since the fort of

Mistassini could

only bo reached by a

further journey of

ninety leagues. This

North-West post was

built at the end of

Lake Mistassini,

while the Hudson's

Bay Company Fort,

called Birch Point,

was erected four

days' journey

further on toward

East Main House.

Leaving the

Saguenay, McKenzie

followed the coast

of the St. Lawrence,

passing by Portneuf,

with its beautiful

chapel, "good enough

for His Holiness the

Pope to occupy,"

after which—the best

of the King's posts

for furs—He Jérémie

was reached, with

its buildings and

chapels on a high

eminence.

Irregularly built

Godbout was soon in

view, and the Seven

Islands Fort was

then come upon.

Mingan was the post

of which McKenzie

was most enamoured.

Its fine harbour and

pretty chapel drew

his special

attention. The "Man

River" was famous

for its fisheries,

while Masquaro, the

next port, was

celebrated for the

supply of beavers

and martins in its

vicinity. The salmon

entering the river

in the district are

stated to be worthy

of note, and the

traveller and his

company returned to

Quebec, the return

voyage being two

hundred leagues.

Since the time of

McKenzie the fur

trade has been

pushed along the

formerly unoccupied

coast of Labrador.

Even before that

time the far

northern coast had

been taken up by a

brave band of

Moravians, who

supported themselves

by trade, and at the

same time did

Christian work among

the Eskimos. Their

movement merits

notice. As early as

1749 a brave

Hollander pilot

named Erhardt,

stimulated by

reading the famous

book of Henry Ellis

on the North-West

Passage, made an

effort to form a

settlement on the

Labrador coast. He

lost his life among

the deceitful

Eskimos.

Years afterward,

Count Zinzendorf

made application to

the Hudson's Bay

Company to be

allowed to send

Moravian

missionaries to the

different Hudson's

Bay Company posts.

The union of trader

and missionary in

the Moravian cult

made the Company

unwilling to grant

this request. After

various preparations

the Moravians took

up unoccupied ground

on the Labrador

coast, in 56 deg.

36' N., where they

found plenty of

wood, runlets of

sparkling water and

a good anchorage.

They erected a stone

marked G.R. III.,

1770, for the King,

and another with the

inscription V.F. (Unitas

fratrum), the name

of their sect.

Their first

settlement was

called Nain, and it

was soon followed by

another thirty miles

up the coast known

as "Okkak," Thirty

miles south of Nain

they found remains

of the unfortunate

movement first made

by the Society, and

here they

established a

mission, calling it

"Hopedale." When

they had become

accustomed to the

coast, they showed

still more of the

adventurous spirit

and founded their

most northerly post

of Hebron, well nigh

up to the dreaded

"Ungava Bay." A

community of upwards

of eleven hundred

Christian Eskimos

has resulted from

the fervour and

self-denial of these

humble but faithful

missionaries. Their

courage and

determination stand

well beside that of

the daring fur

traders.

The Hudson's Bay

Company was not

satisfied with

Mingan as their

farthest outward

point. In 1832 and

1834, Captain

Bayfield, R.N.,

surveyed the

Labrador coast. In

due time the Company

pushed on to the

inlet known as

Hamilton Inlet or

Esquimaux Bay, on

the north side of

which the fort grew

up, know as

Rigolette. Hero a

farm is maintained

stocked with

"Cattle, sheep, pigs

and hens," and the

place is the depot

of the Hudson's Bay

Company and of the

general trade of the

coast. Farther up

two other sub-posts

are found, viz.,

Aillik, and on the

opposite side of the

Inlet Kaipokok. The

St. Lawrence and

Labrador posts of

the Hudson's Bay

Company have been

among the most

difficult and trying

of those in any part

where the Company

carries on its vast

operations from

Atlantic to Pacific.

This Labrador region

has been a noble

school for the

development of the

firmness,

determination,

skill, and

faithfulness

characteristic of

both the officers

and men of the

Hudson's Bay

Company.

Most notable of the

officers of the

first rank who have

conducted the fur

trade in Labrador is

Lord Strathcona and

Mount Royal, the

present Governor of

the Company. Coming

out at eighteen,

Donald Alexander

Smith, a

well-educated

Scottish lad,

related to Peter and

Cuthbert Grant, and

the brothers John

and James Stuart,

prominent officers,

whose deeds in the

North-West Company

are still

remembered, the

future Governor

began his career.

Young Smith, on

arriving at Montreal

(1838), was

despatched to Moose

Factory, and for

more than thirty

years was in the

service, in the

region of Hudson Bay

and Labrador. Rising

to the rank of chief

trader, after

fourteen years of

laborious service he

reached in ten years

more the acme of

desire of every

aspirant in the

Company, the rank of

chief factor. His

years on the coast

of Labrador, at

Rigolette, and its

subordinate stations

were most laborious.

The writer has had

the privilege from

time to time of

hearing his tales,

of the long journey

along the frozen

coast, of camping on

frozen islands,

without shelter, of

storm-staid journeys

rivalling the

recitals of

Ballantyne at Fort

Chimo, of cold

receptions by the

Moravians, and of

the doubtful

hospitalities of

both Indians and

Eskimos. Every

statement of

Cortereal, Gilbert,

or Cabot of the

inhospitable shore

is corroborated by

this successful

officer, who has

lived for thirty

years since leaving

Labrador to fill a

high place in the

affairs both of

Canada and the

Empire. One of his

faithful

subordinates on this

barren coast was

Chief Factor P. W.

Bell, who gained a

good reputation for

courage and

faithfulness, not

only in Labrador,

but on the barren

shore of Lake

Superior. The latter

returned to Labrador

after his western

experience, and

retired from the

charge of the

Labrador posts a few

years ago. It is to

the credit of the

Hudson's Bay Company

that it has been

able to secure men

of such calibre and

standing to man even

its most difficult

and unattractive

stations.