|

DIVISION III.

HISTORY OF TENNESSEE FROM THE TIME OF ITS

SETTLEMENT BY THE WHITES TO THE DATE

OF ITS ADMISSION AS A

STATE.

CHAPTER VII. THE PIONEER.

59. Anglo-American Excursionists Visit Tennessee.—Although

Tennessee had been included as a part successively of three

English colonies, yet none of them had thought it worth their

while to explore or settle the country. The settlement was due

to no concerted or governmental act, but to the agency of the

most "unique and picturesque character of history"—the American

pioneer. The term "pioneer" may be extended to include the first

persons who explored or visited the country. It is especially

used to designate those who made the early permanent

settlements. While there had been no attempt at settlement, or

permanent occupation by the English previous to the

establishment of Fort Iyoudon, in 1756, yet there had been

casual visitors, traders, hunters, and tourists, who had made

excursions into Tennessee. The names of many of these have been

lost to history, but a few have been preserved by the early

historians.

60. The Traders.—Perhaps the first English travelers-who visited

Tennessee were attracted by the hope of gain in trade. In 1690,

i trader from Virginia, named Doherty, visited the Cherokees. In

1730, Adair, from South Carolina, made an extensive tour,

visiting the Cherokees and other tribes. Dr. Ramsey says of

Adair: "He was not only an enterprising trader, but an

intelligent tourist. To his observations upon the several tribes

which he visited we are indebted for most that is known of their

early history. They were published in 1775." In 1740 a party of

traders from Virginia visited the Cherokees. This party employed

Mr. Vaughan as packman. There were, doubtless, many other

traders of whom history makes no mention. Many advantages

resulted from this irregular trade. It was found to be

lucrative, and led to important results. The returning traders

gave glowing accounts of the wonderful resources and fertility

of the western country, and the abundance of game, which excited

a lively interest among the eastern colonists.

61. The Hunters.—Following the traders, came the hunters,

sometimes in company with a trading party, and sometimes in

separate bands. Historians have recorded a few of these hunting

excursions. "As early as 1748," says Dr. Ramsey, quoting from

Monette, "Dr. Thomas Walker, of Virginia, in company with

Colonels Wood, Pat-ton, and Buchanan, and Captain Charles

Campbell, and a number of hunters, made an exploring tour upon

the western waters. Passing Powell's Valley, he gave the name of

' Cumberland' to the lofty range of mountains on the west.

Tracing this range in a southwestern direction, he came to a

remarkable depression in the chain ; through this he passed,

calling it 'Cumberland Gap.' On the western side of the range he

found a beautiful mountain stream, which he named 'Cumberland

River,' all in honor of the Duke of Cumberland, then Prime

Minister of England." In 1760, a Virginia company of hunters,

composed of "Wallace, Scags, Blevins, Cox, and fifteen others,"

spent eighteen months in a hunting excursion along Clinch and

Powell rivers.

62. Daniel Boone.—In 1760 the famous Daniel Boone visited

Tennessee at the head of a party of hunters. It is conjectured

by Dr. Ramsey that this was not Boone's first visit to

Tennessee, although it is the first that has come to the

knowledge of historians. In testimony of this visit, Dr. Ramsey

gives in his history an inscription cut by Daniel Boone on a

beech tree, "standing, in sight and east of the present stage

road leading from Jonesboro to Blountville, and in the valley of

Boone's Creek, a tributary of Watauga. This tree and inscription

is shown in the annexed picture, engraved from a photograph in

the Tennessee Historical Society. There is no doubt of the

genuineness of the inscription, but doubts have been expressed

as to whether it was carved by Daniel Boone. Daniel Boone

visited Tennessee again in 1771, and remained until 1774. Many

other hunting parties prepared the way for the advent of the

pioneers of permanent settlement.

63. The First Negro.—In 17682 an expedition of hunters traversed

the country from the banks of the Holston, in East Tennessee, to

the Ohio River at the mouth of the Tennessee River, passing

along the banks of the Cumberland River, and giving the name to

Stone's River. The party consisted of Colonel James Smith,

William Baker, Uriah Stone, for whom Stone's River was named,

and Joshua Horton. The last-named member of the party, Joshua

Horton, had with him "a mulatto slave," eighteen years old,

whose name is not given. Judge Haywood states that Mr. Horton

left this mulatto boy with Colonel Smith, who carried him back

to North Carolina.

64. The Approach of the Pioneer.—In 1763, the period of nearly

five generations of men had passed since the settlement of

Jamestown in 1607. A new generation now dominated the colonies

who were Americans by birth, and distinctly American in thought,

character, and habit. This differentiation in colonial character

was, however, largely restrained by the influence of English

governors, by constant contact with English laws and

institutions, and by the influx of fresh immigrants who

continued to pour in from the mother country. Along with this

stream of immigrants came the "Scotch Irish." This latter

element inherited the clannish spirit which prompted them to

keep together. They early evinced the desire to found

settlements in which they should be the controlling element.

This tendency, together with their resolute character and

adventurous spirit, constantly prompted them to move further

west. Thus, the Scotch Irish immigrants formed a large element

in the vanguard of the western march of colonization, which

their descendants continued to push further and further

westward. This hardy band of pioneers was now ready to cross the

mountains. The way had been prepared by the Treaty of Paris in

1763, by which the title of France had been ceded to Kuglaud,

and by the various Indian treaties above named.

65. The First Settlers in Tennessee Largely Scotch-Irish.—The

Holston and Watauga were not colonized, as the Cumberland

afterward was, by strong companies moving in concert, under

organized leaders. Their first settlers came in single families

or small parties, with no concert of action, and without any

recognized leader. The Virginia frontiers had now reached the

headwaters of the Holston River, and straggling immigrants

followed that stream beyond the borders of the province, and

formed the first settlements in Tennessee ; supposing their

settlements to be still in Virginia, some families even crossed

the Holston. In 1769 or 1770, William Been, originally from

Pittsylvania County, Virginia, penetrated as far south as the

Watauga, and erected a log cabin at the mouth of Boone's Creek,

where his son Russell, the first native white Tennessean, was

soon afterwards born. His settlement was greatly augmented by

the arrival of small bands of Regulators, whom the tyranny of

the royal governor had driven out of North Carolina. But whether

they came from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, or

Pennsylvania, the first settlers of Tennessee were, in the main,

the same type of people— an aggressive, daring, and hardy race

of men, raised up in the faith of the Presbyterian Covenanter,

and usually comprehended under the general designation of

Scotch-Irish, that people forming their largest element.

66. Origin of the Scotch-Irish.—Ireland, in the time of Henry

VIII, was so strongly Catholic that all the power of that

monarch was not sufficient to establish the Episcopacy on the

island. His effort to do so resulted in a long, bitter, and

bloody war, which was not finally terminated until near the

close of Elizabeth's reign. When it did close, the province of

Ulster, containing nearly a million acres, was found to have

been almost depopulated b)T its devastations. James IV, of

Scotland, succeeded to the throne, and in him the two kingdoms

were united. He conceived the idea of colonizing Ulster with

Protestant subjects. These he chose chiefly from his old

subjects, the Scotch Covenanters, though mainly Englishmen

settled in the southern part of the province.

67. Character of the Scotch-Irish.—These Scotch emigrants were

stern, strict, liberty-loving Presbyterians, who believed in the

Westminster Catechism and taught it to their children. They

resented the pretensions of the Crown to be the head of the

church, and believed with John Knox that the King derived his

authority from the people, who might lawfully resist, and even

depose him, when his tyranny made it necessary. They believed in

education, and followed a system under which every preacher

became also a teacher, a circumstance that had a marked

influence on the educational history of Tennessee. The colony

prospered wonderfully. But these Scotch-Irish as steadfastly

resisted the Episcopacy as did the Irish Catholics, and were

destined to suffer a like persecution. As early as 1636 some of

them set sail on board the "Eagle Wing" for America, but

unfavorable weather sent her back to port in a disabled

condition, and the experiment was not again repeated for half a

century.

68. The Great Ulster Exodus.—Their persecutions continued, with

the exception of a short respite under the reign of William of

Orange. Finally, in the latter part of the seventeenth century,

the great exodus began. It reached its flood-tide near the

middle of the eighteenth century. For some time prior to 1750,

about twelve thousand Irish emigrants had annually lauded in

America. In the two years following the Antrim evictions in

1771, as many as one hundred vessels sailed from the north ports

of Ireland, carrying from twenty-five to thirty thousand

Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, mostly to America. Their experience

in Ireland had peculiarly fitted them to lead the vanguard of

western civilization. Their hereditary love of liberty, both

civil and religious, was strengthened by a long course of

persecution and oppression. Moreover, the constant presence of

danger from their turbulent neighbors had made them alert,

active, resolute, and self-confident.

69. The Scotch-Irish Settle on the Frontiers.—The Scotch-Irish

reached the interior of America in two streams. The earliest and

largest poured into Pennsylvania through the ports of New Castle

and Philadelphia, whence it moved southward through Maryland and

Virginia, up the Potomac and Shenandoah valleys, and along the

Blue Ridge into North and South Carolina. There it met the

counter stream flowing in from the south, mostly through the

port of Charleston, but in smaller numbers through those of

Wilmington and Savannah. All along the frontiers, from Pittsburg

to Savannah, they interposed themselves as a conscious barrier

between the sea-board settlements and their Indian foes.

70. The Scotch-Irish in America.—The Scotch-Irish were

everywhere a masterful people. In Pennsylvania they were not

regarded with favor. In 1725 the president of the province

described them as bold, though rude and indigent strangers, who

frequently sat down on any vacant land without asking questions.

He expressed the fear that, if they continued to come, they

would make themselves proprietors of the province. They were

always jealous of their liberties, and ready to resist

oppression with blood. In North Carolina they have made two

counties famous — Mecklenburg for the first Declaration of

Independence, and Orange for the battle of the Alamance.

CHAPTER VIII. THE WATAUGA ASSOCIATION.

71. The North Holston. Settlement.—The first settlements in

Tennessee, as we have seen, were but extensions of the frontier

settlements of Virginia. They lay north of the Holston River, in

what is now Sullivan County. Lying east of the Indian line

established by the treaty of Eochabar, they received the

protection of Virginia, under whose laws they lived, and whose

authority they supported, until the Walker-Henderson line of

1779 showed them to be in North Carolina. The leading family of

the North Holston settlement was the Shelbys. Gen. Evan Shelby,

who settled at King's Meadows, was a famous woodsman, and

figured prominently in the Indian wars on the border. His son,

Col. Isaac Shelby, distinguished himself at the battle of King's

Mountain. He afterwards went to Kentucky, and became the first

governor of that Commonwea!th.

Footnotes:

ln 1738 the Synod of Pennsylvania, upon tl.e application of John

Caldwell, the grandfather of the great statesman, John Caldwell

Calhoun, sent a commission to the Governor of Virginia with a

proposal to people the valley west of the Blue Rigde with

Presbyterians, who should hold the western frontier against the

Indians, and thus protect the colony, upon condition "that they

be allowed the liberty of their consciences and of worshiping

God in a way agreeable to the principles of their

education."—Scotch-Irish in America, First Congress, p. 117.

On the subject of the Scotch-Irish in America, and particularly

in Tennessee, see the Life of George Donnell, by President T. C.

Anderson. See also the proceedings of the Scotch-Irish in

America, at their various congresses, the first of which was

held at Columbia, Tennessee, in 1879.

72. The Carter's Valley Settlement.—There was another settlement

north of Holston, known as the Carter's Valley Settlement, in

what is now Hawkins County. It was, also, believed to be in

Virginia, but was beyond the Indian line. Its people

acknowledged the jurisdiction of Virginia, but being on the

Cherokee lands, were deprived of its protection. Carter's Valley

took its name from John Carter, one of its first settlers, who

afterward became prominent in the Watauga settlement. These two

settlements lived, during all the historic life of the Watauga

Association, under the laws of Virginia, and had no other

connection with the South Holston settlements than that of near

and friendly neighbors, who stood in common peril from the

Indian wars which commenced with the first struggles for

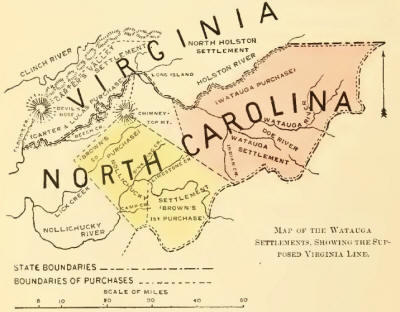

American independence. (See map.) The only distinctive Tennessee

history from 1769 to 1779, was made by the people south of the

Holston River.

73. South Holston Settlements.—There were two South Holston

settlements; Watauga, on the Watauga River, and Brown's, on the

Nollichucky River. The latter was just being planted when the

Watauga Association was formed in 1772, and took no part in its

organization. It was founded by Jacob Brown, a native of South

Carolina, who distinguished himself both in the Indian wars, and

at King's Mountain.

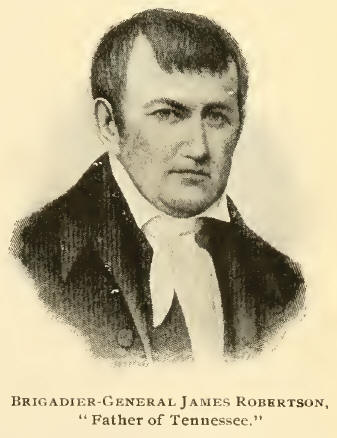

74. James Robertson.—The first decade of Tennessee history

centers in the little settlements on the Watauga River, of which

James Robertson was the most distinguished member. Robertson was

a native of Brunswick County, Virginia, but in his youth moved

with his parents, John and Mary (Gower) Robertson, to Orange

County, North Carolina. He had just reached manhood when the

Regulators began an organized resistance to the oppressions of

the royal government. He had neither wealth nor education, but

his native talent, his resolute spirit, and his inspiring manner

were such that he could neither have been an indifferent

spectator in the stirring scenes of the first year of the

Regulators, nor could he have passed unnoticed through them.

75. Robertson Determines to Leave North Carolina.—During the

year or more of quiet dejection following the dispersion of the

Regulators in the fall of 1768, Robertson determined to seek a

home beyond the reach of British oppression. Accordingly, in the

spring of 1770, he found the beautiful valley of the Watauga,

where he accepted the hospitality of one Honeycutt, raised a

crop of corn, and returned for his family and friends. On the

trackless mountain he lost his way, and would have perished but

for the providential relief afforded by two hunters who chanced

to discover him when his strength was fairly exhausted from

hunger and fatigue.

76. Robertson, the Father of Tennessee.—Robertson was not the

first to settle on the banks of the Watauga. Perhaps that

distinction is properly accorded to William Been. It is certain

Robertson found Honeycutt there on his first arrival. But he has

been justly called the "Father of Tennessee" in recognition of

his eminent services to its infant settlements. It is true, his

name is more intimately linked with the history of the middle

portion of the State, but his public services here antedate the

settlement of the Cumberland Valley by a period of nearly ten

years; during this time he was the leading spirit of the Watauga

settlements, where he proved himself in every way worthy of the

affectionate title he has received. He had an elevation of soul

that enabled him to take upon himself the burden of the whole

community. He was wholly unconscious of self. He never sought

popularity, nor honor, nor position. If there was a service too

humble to attract the ambitious, a post so perilous as to make

the brave quail, or a duty so difficult as to fill every other

heart with despair, that service or post or duty was accepted as

a matter of course by James Robertson. And his head was so cool

and clear; he had such a brave, resolute and devoted spirit; and

his vigilance was so alert and active, that success followed him

like the blessings of a special providence.

77. The Watauga Settlers Ordered off.—By the spring of 1772,

wheu the first political organization in the State was effected,

the Watauga settlement numbered many families. Some of them, as

we have seen, had settled there in consequence of the treaty of

L,ochabar, believing that they were within, the limits of

Virginia. But in 1771, Anthony Bledsoe made an experimental

survey from Steep Rock to Beaver Creek, which clearly indicated

that the Virginia line would not falisouth of the Holston River.

This was followed, in 1772, by a treaty between the authorities

of Virginia and the Cherokees, making the Indian line on the

south identical with the line between Virginia and North

Carolina. Under this treaty, Alexander Cameron, an agent of the

royal government, residing among the Cherokees, ordered the "Watauga

settlers to move off.

78. The Indians Intercede for the Watauga Settlers.— His order

placed the Watauga settlers in a most critical situation.

Hitherto, they had relied on Virginia. Now, they found

themselves without laws, and beyond the protection of any

organized government. Being on Iudialwaud which was controlled

by the Crown, .they were without the jurisdiction, as they were

physically beyond the protection, of North Carolina. They could

not obtain title to their lands, either from the Indians or from

the provincial government. Fortunately for them, a profound

peace existed between the colonists and the Southern Indians.

When the British agent ordered them to move back, some of the

Cherokees expressed a wish that they might be permitted to

remain, on condition that they should not encroach beyond the

lands they then held. After that, no further effort was made to

remove them.

79. Settlers Form an Association.—At this juncture a convention

of the settlers was called to consider their anomalous

condition, and to devise means for its improvement. They never

thought of abandoning their homes. They said they were "too

inconveniently situated to remove back," and besides, they were

"unwilling to lose the labor bestowed on their plantations.''

They determined to do two sensible things: (1) To form a

government of their own for the administration of justice in

their settlement; and (2) to lease for a number of years the

lauds on which they lived, conceiving that the King's

proclamation of 1763, prohibiting them from buying the land from

the Indians, did not extend to a leasing. [Petition of the

inhabitants of Washington District, Ramsey's Annals of

Tennessee, p. 134.]

80. Wafauga Adopts the First Written Constitution in America.—

Accordingly, they entered into a written association and

articles for the government of the settlement, which was the

first written constitution adopted by the consent of a free and

independent people in America. [Compare Ramsey, p. 107; Kelly,

in Proceedings of the First Scotch Irish Congress, p. 153;

Allison, in Proceedings of the Seventeenth Meeting of the

Tennessee Press Association, p. 27; Roosevelts "Winning of the

West, Vol. I, p. 184; Caldwell's Studies in the Constitutional

History of Tennessee, p. 27. See also, Dunmore to Dartmouth, May

16, 1774; Bancroft's History of the United States (first

edition), Vol. VI, p. 401, note.] The instrument itself has not

been preserved. Every member of the settlement signed the

Constitution. They adopted for their government the laws of

Virginia, and not those of North Carolina. A court, consisting

of five magistrates, having a clerk and a sheriff, were

appointed to administer the law under the Constitution. This

government continued until the beginning of the Revolution, in

1775, when it was merged into Washington District.

81. Land Leased from the Indians.—A form of government being now

established, and magistrates appointed, steps were immediately

taken to secure the settlers in the possession of the lands they

had so recently been notified to vacate. James Robertson and

John Bean were appointed to negotiate a lease from the

Cherokees. They assembled the Indians near their own settlement,

and for the sum of five or six thousand dollars in merchandise

leased all the land lying on the waters of the Watauga, for a

period of ten years. Afterwards, in 1775, following the

precedent set by Henderson & Co., in their great Transylvania

purchase, the Watauga people bought their lands in fee simple.

Jacob Brown made a similar lease, and purchased on the Nolli-chucky.

John Carter also met the Indians at Sycamore Shoals, and

obtained a deed to Carter's Valley, partly as an indemnity for a

store destroyed by the Indians some years before, and also for

an additional consideration, which Carter was enabled to raise

by admitting Robert Lucas to the firm. The accompanying map,

page 52, shows the boundaries of each of these private

purchases.

82. The First Geographical Division Named for "Washington.— The

Watauga Association never had, nor sought a political connection

with North Carolina until she declared her independence of Great

Britain. Its people had lived in peace under their own

government from 1772 to 1775. When the conflict between Great

Britain and her colonies began in that year, the united

settlements on the Watauga and Nollichucky formed themselves

into Washington District. This was the first geographical

division in the United States, named for the Father of his

Country.

83. "Washington District Supersedes "Watauga Association.—Having

formed themselves into Washington District, they appointed a

Committee of Safety. This was a kind of provisional government

generally adopted by the colonies. Their Committee of Safety was

composed of thirteen members, of whom Col. John Carter was made

Chairman. The Committee resolved to adhere to the Continental

Congress, and acknowledged themselves to be indebted to the

united colonies for their full proportion of the Continental

expense. Immediately after the Declaration of Independence, in

1776, Washington District presented a petition to the Provincial

Council of North Carolina, praying to be so annexed to that

province as to be enabled to share in the glorious cause of

liberty. [Those desiring further information on the organization

of the Watauga Association are referred to the American

Historical Magazine, Vol. III., p. 103, etseq., where the

subject is discussed more in detail. For an admirable discussion

of the "Watauga Commonwealth," see Roosevelt's Winning of the

West, Vol. I., Chapter 7 ; Putnam, pp. 45 to 49; Ramsey, pp.

134-140. See also Caldwell's Studies in the Constitutional

History of Tennessee.]

|