|

It is well known that the Highlands have

undergone a great change within the last thirty years; that the

human population has become less dense, the woolly population

more so; that the old proprietors have nearly all disappeared to

make room for new; that bogs have been drained, and moors

reclaimed, making the "bonny blooming heather" succumb to the

"yellow corn." Much, however, remains to be known of the ways of

the people—how they eat, and how they drink; how they speak, and

how they act; how they live, and how they die. The object of the

following Sketches is to show something of this, and to begin

with a night with drovers and sheep-farmers on the Mull of

Cantyre.

I believe there is no town, district, or

country without a grievance or difficulty. Great Britain has its

neutrality and income-tax; France has its Bourbons, Orleanists,

Imperialists, and gagged press; Russia has its Poland; Austria

its Venetia; Turkey its Principalities ; America its rebellion,

and long bill to pay; and Argyleshire its Mull of Cantyre. I was

guiltless of such wise reflections as these some years ago, as I

started for the pretty well known sunny little town of Oban. I

had heard a great deal about Great Britain, but neutrality was

not practised there at the time, and the income-tax did not

greatly affect me, and as for the grievances and difficulties of

foreign countries, I really cared very little about them; and,

must it be confessed, I had never heard of the Mull of Cantyre

except in my geography lesson at school, until the day I began

my travels, as just mentioned. It was a squally not very

pleasant day as I bowled along on the Glasgow and Greenock

Railway towards the latter town, where I was to join the "Arab,"

which was to sail thence for Oban at four o'clock p.m. I knew

little of steamers, and it never occurred to me that the voyage

might prove anything but an agreeable one. There was a

sallow-faced man sitting opposite to me in the carriage, who

kept constantly looking out at the windows, every now and then

turning up his eyes as if he expected his death-warrant from the

clouds that scudded past towards the east. He carried something

between a portfolio and a parcel on his knee, which he nervously

clutched when he took his eyes off the sky. He looked at me

wistfully at last, and seemed desirous to make some

communication; and as, I presume, he saw that I was ready to

receive it, he leaned forward and said—

"It's rather blowy, I'm thinkin'." I nodded

assent "Weel," continued my fellow-traveller, "that will be

against me."

" No doubt of it, if you are going against

it." "I am goin' ower to Belfast, and I doot it will be roch

wark or we win to Belfast loch; but no so bad as goin' roon the

Mull o' Cantyre to Oban."

This was interesting to me, and he saw it.

"You 'll be goin' that gate?" continued he.

"Yes; but I don't care much for the Mull of

Cantyre."

Of course not, for I knew nothing about it.

"Lucky that for ye, for there will be a

jabble there the nicht, or I'm no judge." This last remark was

uttered after a long look at the sky, and was not very

reassuring.

Immediately on arriving at Greenock I went to

the quay, and found the "Arab" lying uneasily there, the wind

whistling viciously through the rigging, and the steam screaming

and tearing frantically from the steam funnel. I went on board

and got my luggage disposed of, and walked to where I saw a

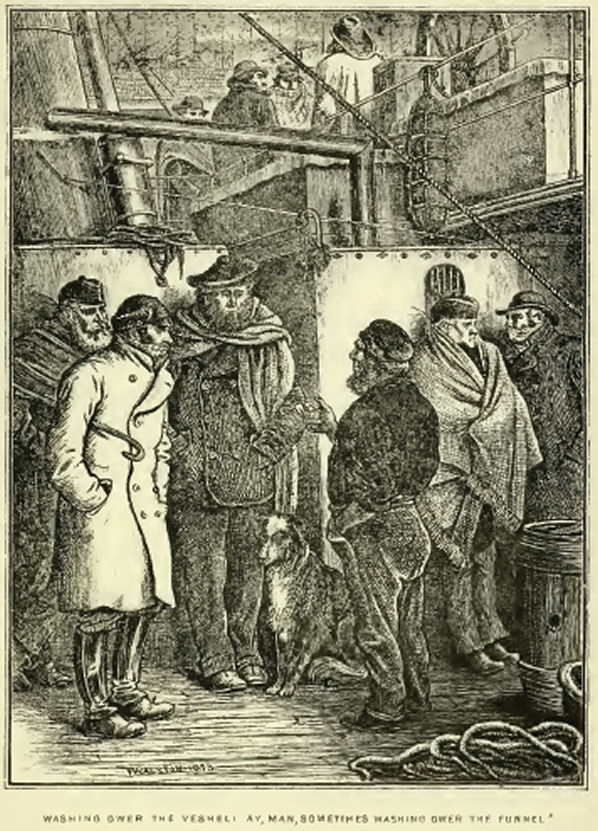

number of people standing round the funnel busy talking, and

having nothing particular to do I listened.

"Ye'll think it'll pe a plowy nicht?" said a

hairy-faced fellow, who had a plaid rolled tight round his neck,

as if he had serious thoughts of doing himself a grievous

injury.

"Ay will it," answered a short squat man in

moleskins, all covered over with coal-dust. "Ye see the clouds,

hoo they chase ane anither; that's a gran' sign o' wind; we'II

hae a dance on the Moil the nicht, or I'm mista'en. There is

plenty o' that afore us, or the winter is ower."

"No toot o' that, but ye're accustomed to it,

and 'ill no mind it."

"We wadna need, Dugald, for mony's the awfu'

nicht we hae o' it on the Mull o' Cantyre."

"It'll pe sometimes washing ower the feshel?"

"Washing ower the veshel! ay, man, sometimes

washing ower the funnel, and near puttin' out the fire on us,

and wad do sae if the smoke didna keep it frae comin' doon. I

mind—"

At this point of the conversation I heard a

bell ring, and my dusty friend disappeared leaving something

very wonderful untold.

After this I went down to the cabin, where I

saw some three or four ladies sitting together in a quiet

corner. I could not help hearing part of their conversation, and

again it related to the Mull of Cantyre. It is unnecessary to

repeat any part of it except the conclusion at which they

arrived, as enunciated by one of the party.

"I have," said the lady, "lived in

Argyleshire for fifteen years, and, but for this dreadful Mull

of Cantyre, I would say it is as pleasant a place to be in, and

as healthy as any part of the world. But I have much there to

make me happy and contented," she added, "and I trust I am so,

and grateful too, notwithstanding of the 'Moil,' and the

wretched night I expect to spend in making the voyage round it."

By this time the conviction forced itself

upon me that Argyleshire had a real grievance, and was to be

felt for, and I began to imbibe a decided dislike to the Mull of

Cantyre, and wondered very much how I had never heard of it

before, when it was so well known to every one else. With this

feeling gaining fast upon me, I again went on deck, and saw

every kind of lumber for the Highlands taken on board. Old beds,

old tables, old chairs, old boxes, old hampers, old every thing,

were knocked about in great confusion; but the principal part of

the cargo consisted of tar barrels. These were rolling in all

directions, and perfuming the boat and all in it in a way I did

not by any means like. There was a number of patriarchal-looking

rams—some with astonishingly tortuous horns, and some with

none—cooped up forward; and as to the number of wild,

savage-looking fellows, with large whiskers, unshaven beards,

and dirty faces, and gaunt but sagacious-looking dogs, their

name truly was legion. All this was soon seen, and I must say it

did not prepossess me with any favourable opinion of the

comforts of the "Arab." The longest voyage I had ever before

made was from Newhaven to Kirkcaldy, and I was therefore not

aware of all the manifestations of a disagreeable one in

prospect, that presented themselves to more experienced eyes

than mine.

After losing a couple of hours of good

daylight, everything was got on board, but certainly not in a

ship-shape condition, and we started for Oban. I like to see

everything going on around me, and instead of again going below

to the cabin, I mounted up to a cross plank

resting on the two paddle-boxes, which I heard them call "the

gangway," and found a good-looking quiet man standing there

looking right before him, and not taking the least notice of

anything but the head of the vessel. I went up to him, and

remarked it promised to be a good night.

"O yes," he said, "it's a good night." He

then looked down to where the tar barrels were crowded about the

deck, and cried, "Take you there, M'Innes, some planks and

confine these sheep well forward, the shepherds will help ye.

You, Beaton, get Gome hands and stow away these tar barrels, and

make things snug for the night."

"Ay, ay, sir," sounded from below.

"You are the captain of the 'Arab?'"

"Yes."

"She is a good boat," I ventured to say.

"Yes, sir, she's a good boat," shortly.

"Is the wind fair, captain?"

"It will do very well if it keeps this way."

"You do not expect a change; do you,

captain?"

"Well, sir, it is difficult to say when to

expect a change and when not. I do not expect any change to

signify."

I observed that he looked at the moon, which

was surrounded by a bright golden ring. The clouds were scudding

past her very fast, and a black cloud stood right ahead of us,

which I would have willingly steered clear of, if that were

possible. I saw the captain every now and then looking to see

that his orders about the tar barrels had been carried out, and

I confess that a sort of disagreeable idea began to creep upon

me that we were to have a stormy passage round the Mull of

Cantyre. I kept up on the gangway to see how matters were likely

to go, and I began to perceive a decided heaving under me. This

suddenly increased, and the steamer gave a plunge that made my

heart start to my mouth. Still the reflection of the moon shone

brightly on the water, and there was plenty of laughing and

talking on all sides of me, which made me think, at all events,

that there was no danger. The plunges became more frequent, and

by and by the vessel began to go down sideways, and then come up

with a sudden spring that was very unpleasant to me. Shortly

after this a bell rang, and I saw a man making his way towards

me, and with much ingenuity avoiding the many obstacles that lay

in his path. He would dive under one thing, round another, and

lightly step over a third. I am quite certain that I saw him

make a stepping-stone of the body of a recumbent Celt, almost

without being noticed. At last he reached me and said,—

"Tea is ready, sir; will you be pleased to

take some?"

"Well, I suppose I had better."

"This way, if you please, sir" and away he

went in the same eel-like manner as he came, but every moment

looking back and saying, "This way, if you please, sir."

I soon found following him a matter of no

small delicacy and difficulty. Every place that was not taken up

by tar barrels and other unsavoury lumber was occupied by human

beings, who lay about in inconceivable places, and I found

myself tumbling and floundering among them, kicking this one,

trampling upon that, and leaving behind me a track of "oich-oichs"

and guttural benedictions which I did not pretend to understand.

My first feeling on getting into the cabin was one of dislike to

everything I saw. There was a smell of fish, flesh, and fowl,

combined with a close and oily atmosphere, and the fumes of

toddy and bilge water, which prejudiced me against the display I

saw of dish covers, cups, and plates, surrounded by a goodly row

of weather-beaten, rugged faces, seemingly intent upon some

expected event of considerable interest.

"This way, sir, if you please," said my

friend the steward, who steadied me into a seat, and then

bustled out of the cabin. There was solemn silence for a few

minutes, and I observed my neighbours never took their eyes off

the dish covers, and one or two began to finger their knives, as

if impatient for the word of command. The captain made his

appearance at the door, and there was a simultaneous move of

satisfaction. He sat down quickly, said grace, and instantly off

flew the dish covers, giving to view an enormous quantity of

substantial fare. It was worth while seeing the earnest alacrity

with which the passengers turned-to.

"Mr. Finlay, I'll trouble you for a bit of

feesh."

The party addressed was at the moment

conveying a liberal allowance of ham and eggs to a capacious and

willing mouth, and gave a questionable grunt before he seized

the fish slice and helped the requisitionist. The clatter of

knives and forks went on for a long time with scarcely an

interruption, except now and then that one would ask another for

something that he fancied.

"Mr. M'Craw, I'll thank ye for a little

cheecan," and forthwith the cheecan was consigned to the tender

mercies of a case of powerful grinders. I do not know that I

ever before saw good cheer done such ample justice to. The

assailants, however, began by and by to give in, one by one, but

some of them returned more than once to the charge, and seemed

reluctant to give up to the very last. Indeed it is difficult to

say when some veterans would have, finally ceased, had not the

steward commenced operations whereby he very summarily cleared

the tables.

For my own part, I felt little disposed to

eat. Every time I attempted to swallow anything, there was a

repelling movement inside, which, as I did not understand, I

marvelled at. When tea was over, I rose to take possession of an

unoccupied sofa, but of a sudden felt as if the top of my head

had flown off, and I dropped into my seat again in much

perplexity. An intolerable heat came over me, and the

perspiration came streaming out of every pore. The steward came

past, and I said to him—

"The room is too close; will you open the

window?"

"All battened down for the night, sir."

"Steward, what can the matter be with me? I

feel very uncomfortable."

"Perhaps you are getting sick, sir," without

even attempting to throw a grain of compassion into his voice;

"a little brandy might do you good, sir."

"Bring me some;" and forthwith it came, but I

cannot say that I experienced much relief from this sovereign

remedy for sea-sickness.

The rest of the tea-party still lingered

about the table, as if there yet remained something to be done,

and my helpless state, for I may now call my state helpless,

attracted their attention. They instantly began to prescribe.

"A pottle of porter did me goot once," said

one.

"I think ale's petter," said another.

"Goot room (rum) is apout the pest thing I

know," said a third.

"If ye tak my advice," said a gaunt old

fellow, with a pair of threatening eyebrows, "ye 'II gie a rub

to the pit of your stamach wi' a little turpentine and vanagar."

"We el, chentlemen," said a round-faced jolly

little Celt, "I wadna gie a drap of good whusky for them aal put

together."

"Ferry goot observation, sir," responded on

all sides.

At this time a fine old man, with a shrewd

intelligent face, came quietly up to me, and advised me to lie

down on the sofa, and keep very quiet in whatever position I

felt most free from the intolerable feeling of sickness and

nausea I had. The good old fellow, God bless him, helped me to

the vacant sofa himself, and made me snug there. I lay flat on

my back, and was greatly relieved; but the least

movement brought back the sickness. My

feelings and faculties were in a preternatural state of

vigilance and susceptibility, and a mouse could scarcely move in

the cabin without my hearing her. Under these circumstances,

none of the sayings and doings of my fellow-passengers escaped

me, and for a time they nearly drove me distracted. As the

sickness went off, however, I became more reconciled to them,

and by and by I was for a time almost unconscious that there was

any one in the cabin, though I afterwards remembered every word

that was uttered, as well as every thing that was done.

"I think, chentlemen," suggested a

sober-looking young man, with dark hair and a lively twinkle

about the eye, "that we would pe the petter of something warm

aifter our tea."

"Ferry goot observation" was repeated

simultaneously by the whole company, who with astonishing

unanimity seated themselves round the table.

"What will ye pefor, chentlemen?" asked the

first speaker "will we have prandy?"

"Prandy is a fery goot trink, there is no

toubt," answered a round-faced drochy, with very broad shoulders

and large whiskers, "and I like it fery well."

"So do I," and "so do I," was repeated by

several.

"Weel chentlemen," said an old man of immense

stature, wearing a very broad hat, "I have nothing particular to

say against prandy, altho' three or four smaal tastings that I

took of it the other morning pefore preakfast at Falkirk did not

agree with me. Put to tell ye the truth, I would rather whusky;

the real Talisker is the thing for me."

This brought down a shout of applause, and

the Talisker was accordingly ordered.

"It's a fine speerit, the Talisker," said the

stout gentleman, looking round.

"Ou ay," said a dozen voices, "a fine speerit."

"There's no a petter made. That is the real

right thing, chentlemen, I would know it anywhere," continued

the stout gentleman, "and weel I might, for many's the trop of

it I have drank. No man knows goot whusky petter than Talisker

himself; tacent man, Talisker."

"A goot man," sententiously pronounced a

leathern-jawed middle-aged man, dressed in home-made shepherd's

plaid clothes.

"A goot man and a goot whusky is goot

company," answered the gentleman that suggested the brandy.

"Chentlemen," said the stout man, in a voice

that all understood to preface a toast, "chentleman, I see aal

your classes are filled; I think, after the Falkirk we have had,

we may trink goot markets."

"Goot toast, Glenbogary;" "excellent toast;"

"no one can object to that toast;" "aal feels interested in goot

markets;" "the whole country is the petter of goot markets,"

were the various remarks suggested by this toast, which was

drunk with much good-will.

"I heerd," said the abominable old fellow

that wanted me to burn myself up with turpentine, who turned out

to be a stray Lowlander that had settled in the North, "that ye

got a lang price for yer queys, Glenbogary."

"What did ye hear, Mr. Chaik?" (meaning

Jack.)

"I heerd twenty punds for ane."

"Forty for two, and fifty was got for them

the next day, but the queys was goot."

All expressed astonishment and admiration,

which greatly flattered Glenbogary.

"Tell us aal apout it" demanded several

voices.

Glenbogary took a deliberate gulp out of his

tumbler and commenced,—

"Chentlemen, since it is your pleasure, I'll

tell you aal apout it. I thought I would take a turn to Falkirk

as usual, although I had nothing to sell there, and when leaving

home it came into my head that I might take some peasts with me

to pay my expense. So I sent away the two queys, one of them is

pranded and the other plack. People looked at them as they went

along, and I heard them saying, 'Fine animals,' 'goot peef,' and

observations of that kind; and when I got to the toun of

Stirling, out comes a fat short pody, and says he to me, 'Are

them queys yours?' 'Ay, they 're mines yet,' says I. 'Will ye

sell them?' says he. 'Yes,' says I. 'What are you seeking for

them?" says he. 'Forty pounds,' says I. 'I 'll gie ye

thirty-six,' says he. ' I 'll no take a penny less than forty,'

says I. He then took another look at them, and pressed me to

take thirty-six pounds, then forty with four pack, put I would

not, and went on my way to Falkirk. The night pefore the tryst,

who comes up to me put Peter Lamont from Atholl. Ye 'll aal know

Peter. He took a goot long look at the queys, and then he turns

to me and asks my price—'Forty pounds, and no a penny less.'

'They're mines,' says Peter, shaking my hand, ' and I 'll take

them off your hands in the morning, and pay the money now or

then.' 'The money any time you likes, Mr. Lamont,' says I, 'and

the queys now or never.' 'Say ye sae,' says Peter; 'now then be

it.' Peter is a sure hand. Weel, chentlemen, I sees Peter next

evening, and asks him if he had sold the queys. 'Oh yes,' says

Peter, 'I sold them, and made of them too.' 'How much, Mr.

Lamont>' 'Ten pounds.' 'Ten pounds! Peter, you're choking. Fifty

pounds for my two queys! that was a price.' 'That is just the

figure I sold them for to an Englishman that wants to gain a

prize wi' them, and I wish he may.' Now, chentlemen, that is the

whole story. Put the queys was goot, and the price was goot."

"And the story is goot," answered Mr. M'Craw.

"I'll pe pound there wasn't a pair of queys like them at Falkirk

this many a day. Twenty pounds for a quey! that is a price."

"Forty pounds for two queys, and fifty the

next day," said Glenbogary, as setting the matter in a clearer

point of view, "put the queys was goot."

"Ye maun hae gien them oil-cake," said Mr.

Jack.

"I did not, sir," replied Glenbogary very

decidedly. Mr. Jack still looked dissatisfied.

"Tell us their age, and how reared, Glen,"

demanded Mr. Finlay, who wanted the brandy. Before doing so,

however, another supply of Talisker was placed on the table, and

the tumblers were promptly replenished.

"You want to know their age, and rearing,

chentlemen. You will know it then, chentlemen. The mother of the

plack came from Barra, out of the Colonel's fold, and the mother

of the pranded from Harris, old Tonalt Stewart's fold, poth as

goot preeds as anywhere. Weel, the plack; no, it was the pranded;—no,

but it is no matter; the one was three years old on the 3d of

April, and the other fourteen days later. Then as to the rearing

of them. Chentlemen, they got their mother's milk, every trop of

it, and they never were hungry again. 'Deed, chentlemen, I don't

like hungry man or peast apout me."

"Ferry goot observation, sir," was repeated

here with much emotion.

Mr. Jack did not join in this mark of

confidence, but mumbled something between his teeth about

oil-cake, and shook his head sceptically.

"Pless me, Maister Chaik," said Mr. Finlay,

"ye wat refuse anything. Glenbogary has told as plain as any

English how the queys was porn, pred, and prought up, and ye

look as if ye thought that he wat cheat people as the old Carles

of Achanadrish tid when they used to went to the market."

"Mr. Finlay," answered Mr. Jack solemnly, "I

am no Sgien to cheatin' mysel', and I dinna like folks that is;

but for a' that has cam and gane, I think the queys maun ha'e

gotten oil-cake."

"It matters ferry little, Mr. Chaik," said

Glenbogary with warm dignity, "what you or the like of ye

thinks. Put my advice to you is, when ye py accident find

yourself among chentlemen, to pehave yourself like a chentleman,

and no like an ill-put-thegither low-country nowte as ye are."

"Weel, Glenbogary," answered the impervious

Mr. Jack, "whether ill or weel put thegither, I maybe will haud

the-gither as lang as yoursel'."

As Glenbogary was about to make a suitable

reply, the vessel gave a plunge that made the glasses tumble

about, and a good deal of liquor was spilt. There was

considerable commotion, and the warmth that began to manifest

itself was cooled, and the embryo quarrel forgotten by the time

things were got into their proper places, and a new supply of

Talisker was on the table. When the glasses were once more

charged, a short squat man, with a lively pair of grey eyes,

large whiskers, between a yellow and a grey, and a sharp hooked

nose, got up. He seemed to be liked by the rest of the company,

and no wonder; his laugh was the loudest and merriest, he had

most to say, but principally to those immediately around him,

and there was none among them that took his tipple with more

scrupulous fairness. He no sooner stood up than there was a

general cry of "Scoo-darach." I wondered what was meant, and

thought if I had been hailed by such a cognomen, I should be

very angry. He however bowed, as if flattered by his reception,

from which I correctly divined that Scoodarach was his

patronymic.

"Chentlemen," commenced Scoodarach, "I

pelieve it is pretty fresh weather outside" (he had to hold hard

by the table to prevent being pitched off his feet), "and I

cannot see the reason why we shouldn't refresh ourselves inside"

(hear, hear, and ferry goot observation). "Chentlemen, we have

here a chentleman that is an honor to the whole country, and I

challenge the world to produce another man that got twenty

pounds for a quey at Falkirk."

"Forty pounds," cried Glenbogary, "and fifty

pounds the next day."

"Yes, chentlemen," resumed Scoodarach, "forty

pounds, and fifty the next day; altogether ninety punds !"

"Guide us! Scoodarach," interrupted Mr. Jack,

"ye're no gaun to say that Glenbogary got ninety punds for his

twa queys!"

"I says more, Maister Chaik. They were worth

a hundred to any man that took a fancy to them. (Great applause,

and Mr. Jack refused a hearing.) Then, chentlemen, as my friend

and your friend Glenbogary is so well worthy of our pest thanks

for the honor he has prought upon the country, we 'll trink his

health in full pumpers."

Very great honour was done the toast—heel

taps were out of the question. Glenbogary got up quite overcome;

but as the labouring of the vessel made it difficult to stand,

he sat down immediately, and begged permission to return thanks

sitting, which was of course granted.

"My tear friends," commenced Glenbogary,

affected, "I wish I had the tongue of Donach Ban, the bard, to

speak for me. I would then pe aple to do chustice to my heart.

Ye have tone me creat honor, chentlemen, and I am ferry much

opliged to ye aal. I am getting an olt man now. Chentlemen, I

have stoot thirty Falkirks without missing one." (Hear, hear,

and applause, which encouraged a young man that had said nothing

before, doing every justice to Talisker all the time, however,

to say, "My father stand thirty-five, and he is alife yet.")

"Tid he ever get twenty pounds for a quey

there ?" broke in Mr. Finlay.

"Forty for two queys," persisted Glenbogary,

"and fifty the next day; put the queys was goot."

"Put, Mr. Finlay," said Scoodarach, "how tid

the Carles of Achanadrish cheat when they went to the fairs?"

"Eh, Scoodarach! I thought everypody heard of

them. The way they tid was this: Pefore they would start with

their horses they would put a number of peats round their fires,

and turn out their wives and bairns; then one would go to his

neighpour and ask him if he was to send a horse to the market

The answer was 'yes' of course. 'I 'll puy him.' 'What will ye

give?' I will give so much, peing always a pound or two more

than the prute was worth. This offer was refused, and the

offerer wat hasten home, and wat in his turn pe called upon in

the same way, and the same scene pe gone through. After every

one that was to send a horse to the market had got his offer,

they wat aal go away to the fair. Well, when they got there they

asked a few shillings more than they had peen offered at home.

'That is a great teal too much,' the purchaser wat say. 'Oh no,'

the seller wat say, 'I was offered within three shillings of it

at home.' 'Impossible!' 'May I never again see those I left

around my fireside if I was not.'"

"The auld scoonrels," said Mr. Jack, "they

should ha'e been banished."

"Well, Mr. Chaik," answered Mr. Finlay,

"whether they should or no, and whether they was or no, you'll

find none of them in the country now."

"Weel, I am thinkin' it's no a bad riddance.

But whar ha'e the rogues gane till?"

"Some of them is in Australia, some in

America, some on the sea, and some in their graves. Poor men!

sorry they were to pid farewell to the prown hills of the

Highlands; put the times was against them, and they were aal

sent away."

"Noo, Mr. Finlay, we'll say nae mair aboot

them wi' your leave," said Mr. Jack, who was warming to the

work; "but I am of opinion that a drap mair of Glenbogary's

frien' Talis-ker wad do us nae hairm. What say ye a',

gentlemen?"

There is no earthly doubt what they would

have said, if allowed to speak. This, however, they were not;

for just as a burst of approval was about breaking out, a thin

meagre-looking man who had sat the whole evening with his plaid

drawn tight round his throat, and enveloping the lower part of

his face, only allowing easy access to his mouth, a road

travelled very often by the glass which he seldom let out of his

hand, started fiercely to his legs. This, however, was of very

little use to him, as he as suddenly disappeared under the table

from the rolling of the vessel. He was up in an instant, and his

temper by no means improved by the disaster he had met with. He

looked about him as if he would annihilate all present. His rage

prevented his uttering a word for a few moments. At last he

blazed out "Talisker! Talisker!! Talisker!!! Who is Talisker

that we should pe trinking him? He is no fit for shentlemen to

sit upon. I say, Long Shon."

"Preserve us a'," said Mr. Jack in

considerable astonishment, "is the man wud? What does the crater

mean?"

"I mean," retorted the irate Celt, "that I pe

no more a crater nor you; and I mean that Long Shon makes petter

whusky nor ever cam' out of Talisker's pot."

Glenbogary struck his fist on the table, and

silence ensued.

"My coot friend, Mr. Cameron, it is natural

you should pe for upholding your own countryman, and no man has

more respect for Long Chon than I have; put pefore we can admit

that he is petter than Talisker, I would like to put one

question to you. Mr. Cameron, where does Long Chon get his

watter from?" This question was put with a solemnity that made

the whole company turn up their eyes, and it quite posed Mr.

Cameron, and, after a short pause Glenbogary went on, "Mr.

Cameron, Talisker's watter comes over eighty faals pefore it

reaches his pot."

"Eighty faals! eighty faals! eighty faals!"

repeated by a dozen voices. "That must be goot watter, and make

goot whusky.—Eighty faals!!! "

"It maun be gaen weel saddened aifter sic

tumbling," remarked Mr. Jack, "that maun be said, and doobtless

it maks pleasant drink; but as Mr. Cameron is so fond o' doin'

the thing, I dinna see why we shudna tak his treat of Lang

John."

This suggestion proved extremely to the

liking of the company, and there was such a cheerful

acquiescence on the part of every one that a remonstrance as to

his giving the treat died away on the tongue of Mr. Cameron, and

he ordered a supply of "Long John" in a way that would make one

believe that he was in a mortal rage at the steward. When the

tumblers were filled and tasted, he looked round for the

company's approval of his taste, and as they were drinking at

his expense, he of course obtained it; and Mr. Jack proposed his

health, which was drunk with all the honours.

The applause with which the toast was

honoured had not entirely ceased when a small door nearly

opposite to me opened, and a round grey head came cautiously

out, and then a round short figure dressed in whitey brown

clothes of good quality and make. This personage no sooner

appeared than a shout of "Welcome Mr. Tops!" sounded from all

sides of the table, and the individual so named slowly

approached his friends, holding by every available object to

prevent his being tumbled over by the rocking of the vessel.

"Mr. Tops," whose real name was Dobbs, was an Englishman, and

his round smooth ruddy face presented a decided contrast to the

shaggy and gaunt physiognomy of the topers at thetable. "Sit ye

town, Mr. Tops, sit ye town," and room being made opposite

Glenbogary, Mr. Dobbs was soon seated there with a steaming

tumbler of "Long John" before him.

"We were chust drinking Mr. Cameron's health

when ye cam in, Mr. Tops," said Scoodarach, whereupon Mr. Dobbs

did honour to the toast.

"Perhaps you'll give us a toast yourself, Mr.

Tops'?"

"I'll be very happy to do so, gents, since

you call upon me."

"Mr. Tops' toast—no taylight."

"Well, gents," commenced Mr. Dobbs, "in

responding to the call you have made, and seeing that your

glasses are filled, I propose the health of the Lord-Lieutenant

of the County."

"A ferry goot toast," and great cheering, and

no heel taps.

After this there was a short pause, as if the

whole party were thinking. At last Mr. Cameron got up like a

tiger, and, looking fiercely at Mr. Dobbs, asked him "who the

tefil the Lord-Lieutenant is?" This question was hailed with

"hear, hear!"

Mr. Dobbs stood up with difficulty, and,

looking about him with a pair of large light prominent eyes,

said, "Gents, the Lord-Lieutenant is a man that knows his duty,

he is the right man in the right place." He then sat down with

the air of a man that had done his duty. But Mr. Cameron was not

to be so satisfied. He started up again, and, casting a glance

all round, as if challenging all the world, shouted at the top

of a shrill voice, "Tamn the Lord-Lieutenant—who is he?"

This raised the spirit of the British lion in

Mr. Dobbs, whose face got very red. He gave the fiery

Lochaberman as hostile a look as he could muster, and said, in a

very decided way, "I will not tell you."

This would have brought on a crisis, but

Scoodarach got up and said with great solemnity, "Chentlemen,

poth Mr. Tops and Mr. Cameron is right, and when I tells Mr.

Cameron that the Lord-Lieutenant is a fine teer-hound tog that

Locheil sent as a compliment to a friend of Mr. Tops' in

England, he will never again tamn the Lord-Lieutenant." This

explanation elicited great applause from the company, and Mr.

Cameron got hold of Dobbs' hand, and shook it till that

gentleman's eyes watered. Perfect harmony having been restored,

Mr. Finlay asked Dobbs if he sold his cast ewes. "Yes," answered

Dobbs, who had scarcely slept off the effects of a previous

potation, "and got the highest price at the market for them."

"That's pefore the luckspenny was taken off

it?"

"I never give luck-penny."

"You never gives luckspenny! Weel, I know

ye're a goot hand at a pargain ; would you like to puy a fine

lot? I 'll sell ye the Tomsrachaltney yowes."

"I did not know they were yours to sell."

Neither they were, as all well knew, and Mr. Dobbs at first

suspected.

"Well! ye can try me, Mr. Tops; I 'll give

them to ye for 18s."

"I take them delivered in Glasgow in

October."

"Tone, Mr. Tops; they are yours."

"That is a fair pargain," resounded on all

sides.

"Yes, it is a fair pargain," said Scoodarach,

"and we'll make a note of it."

This proposal rather startled Mr. Dobbs, the

Tomsrachaltney lot being a heavy one evidently; and he did not

imagine that Scoodarach was in earnest, thinking they were not

his.

"Between friends it is not necessary to make

a note oi a bargain," suggested Dobbs.

"Oh, Mr. Tops! oh, Mr. Tops!! you are an

Englishman," was repeated on all sides.

"Yes, I am proud of being an Englishman,"

said Mr. Dobbs patriotically.

"Mr. Cameron will make a note of it," said

Scoodarach, which made Mr. Cameron look as if he would demolish

him.

This was agreed to, and Cameron got hold of a

dirty piece of paper, and commenced writing on it with pencil.

But it would take a better scribe than he evidently was to make

a job of it—what with the drink he had taken, what with the

pitching of the vessel. After indescribable exertions, he handed

the note to Scoodarach to read and sign. Reading it was out of

the question, but both parties signed it—Dobbs with his full

name, and Scoodarach with a few scratches that no one could make

anything of. "Now, Mr. Cameron, ye 'll sign as a wutness to the

pargain, and you too, Mr. M'Craw." Both signed.

"How many tid ye pought, Mr. Tops?" asked

M'Craw.

"Why, I bought the whole."

"I tidn't say that," said Scoodarach.

"Yes you did," retorted Dobbs, who was

getting "very fu'."

"Was it the whole of the tops, or the whole

of the shots, Mr. Tops?"

" It was the whole of both, and no mistake.

Come now, sir ; no nonsense."

"Nonsense, Mr. Tops! I'll refard it to the

wutnesses. What to ye say, Mr. Cameron?"

"I say they are to pe telivered in Clasgow in

Octoper."

"Put how many?"

"I tell ye, they are to pe telivered in

Clasgow in Octoper," in wrath.

"Yes, but what is?" inquired Dobbs.

"To ye tare to tout my word?" said Cameron,

trying to get up, but he was held down by the rest

"I want to know," said Dobbs emphatically,

"what the bargain was? You wrote it down, and are referred to.

What do you say now?"

"I say," screamed Cameron, "they are to pe

telivered in Clasgow in Octoper. Can you refuse that?"

"I refuse nothing; but tell me how many sheep

are to be delivered to me?"

"Sheep! I ton't care for you or your sheep, I

put town that they are to pe telivered in Clasgow in Octoper,

and that is the pargain, whatever ye may say. I am refard, and

that's what I say."

Mr. Dobbs, greatly aggravated and

considerably drunk, stood up, raised his clenched fists above

his head, and looked as if he had been seized with apoplexy. "I

deny it. gentlemen, I call you to witness that he refuses to

tell me the bargain."

Mr. Cameron looked at the bottle as if he

would fain throw it at his opponent's head, but being half full

of "Long John" he thought better of it. "I tell ye, and if ye

werena a prute of a Sassanach, you watn't have asked it again,

that I wrote town that they are to pe telivered in Clasgow in

Octoper. To you say that I titn't write town the truth?"

"Damn the truth!" cried Dobbs, at his wits'

end.

"Oh! oh!! hoh!!!" sounded round the table in

different tones, which perfectly overwhelmed poor Dobbs, who

crawled from the table and sat alone in a corner, looking very

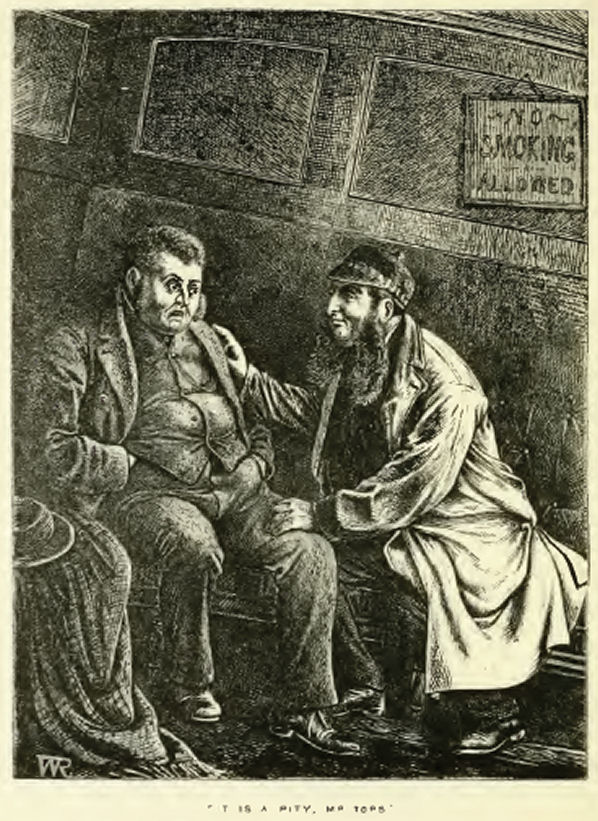

sulky. By and by Scoodarach got up and went to him, and

commenced in a low condoling voice,—

"Well, Mr. Tops, ye tidn't get chustice

altogether from Mr. Cameron, who should have told ye the pargain.

It is a pity that ye were in such a hurry puying the yowes, as I

tidn't intend they should pe more than 15s., and they are

scarcely worth so much. There is chust 2000 of them, and your

loss will pe apout £500. It is a pity, Mr. Tops."

Dobbs' face, drunk though he was, looked so

remarkably blank after he received this gratuitous piece of

information, that Scoodarach seemed to have difficulty in

keeping his gravity.

"What did you say, sir; my loss would be

£500!"

"That at least, Mr. Tops."

"Bless my soul," said Dobbs, "are you

serious? Why, it was not fair of you."

"Chently, Mr. Tops; take care what ye say.

Ye'll no get out of the scrape that way."

"Well, then, how can I get out of it?" asked

the unfortunate man in perturbation of spirit.

"Now, Mr. Tops, ye speak reasonable. I'll

take £50, and let ye off the pargain."

"Fifty pounds! No, no, that 'ere is too much.

Will you take five pounds?"

"Five pounds! Mr. Tops, ye are laughing at

me. Five pounds instead of fifty pounds'? What to ye take me

for?"

"Come now," said Dobbs persuasively, "take

the five pounds."

"I'll tell ye what I'll to, Mr. Tops. I have

known ye long, and ye 're a tacent man, and I'll let ye off for

three pottles of wine."

Dobbs grasped his hand as if he had a

benefactor, and was so overcome with gratitude that he could not

utter a word for two minutes.

The two then joined the rest at the table,

and the wine was called for. When it came they all filled their

glasses and tasted it, then shook their heads, and quietly took

the whisky bottle and put a "smaal drappy o' 'Long Chon' in to

make it trink fit for Christians."

"Tid ye settle, chentlemen?" inquired M'Craw.

"Ooh! Mr. Tops is a chentleman," answered

Scoodarach, looking all innocence.

"You are a gentleman," said Dobbs fervently.

"I will maintain that 'ere in any company."

"Put are they to pe telivered in Clasgow in

Octoper?" asked Cameron, looking dangerous.

"Yes, yes, Mr. Cameron, they are."

The wine and whisky mixture told upon Dobbs,

who soon became unable to sit at the table, and the steward

helped him away. He no sooner disappeared than Scoodarach told

how he had fooled him, and this brought on a lively

conversation.

"To ye mind Tonalt Plack, that kept the

public at the Ferry?"

"Yes, yes, Glenbogary; we aal knew Tonalt."

"Weel, one tay I was crossing at night, and

Achanduin and me stayed at Tonalt's house till the morning. We

were in ped together when Tonalt comes in—he is a shrouwd

fellow, Tonalt—and says Tonalt, 'Glenbogary, what am I to do

with a Sassanach pody that came yesterday, and stayed aal night?

He is up now, and going away, and he is asking me to give him my

pill, and he hasna paid for what he cot, instead of his having

money on me. He'll never get my pill whatever,' said Tonalt.

'The bodach is wanting to cheat ye, Tonalt,' said Achanduin,

'put we'll stand py ye? Will ye?' says Tonald. 'Then if he tries

that, we'll see which is the pest man.' With that Tonalt goes

out, and we heard him saying to the Englishman, 'So ye'll pe for

getting my pill, for how much?' 'None of your impertinence,'

says the Englishman. 'What is that?' says Tonalt. 'Is it another

pill? I'll give ye my pills immediately,' says Tonalt, 'and

there is one of them;' and we heard a creat tramping as of two

men fighting, so we chumped up, and found Tonalt and the

Sassanach pusy at each other. They were poth stout and supple,

and it was pretty to see them, and we looked at them for a

while. Put the Sassanach had cunning plows, and Tonalt got some

pad clours, so we went petween them, and separated them. The

Englishman was in a rage, and wanted to take Tonalt pefore a

magistrate, put when we explained Tonalt's ignorance, he laughed

as much as we tid, and gave him half a crown when going away.

That Englishman was a real chentleman, no tout."

When Glenbogary finished his story, he got

up, and called for the cabin boy, who seemed to be a protege of

his, and after holding a private conversation with him in

Gaelic, the boy went off. The old grazier got his broad hat, and

stuck it on the front of his head, faced right at the door where

the boy had disappeared, steadied himself, and drew his mouth

back twice almost to his ears, each time giving a loud

aspiration between a grunt and a snort, and made a very

ludicrous attempt at a dignified march to the door, from which I

saw the tails of his coat disappear as if he had been shot out

of a huge cannon, the vessel having given a sudden lurch.

"No tout Glenbogary is a very tacent man,"

said Scoodarach, "and he got a lairge price for his queys,—

fourty pounds for two queys! Fery few people tid that. You think

they got oil-cake, Mr. Jaik, to ye no?"

"Weel, after Glen said that he didna gie them

ony, I am boond to believe him. But it's a lang price for twa

beasts aff the graiss. I didna think there was graiss in the

hielands that wad fetch them up to sae muckle money."

"Tyree wat make them petter nor no other

place," said M'Craw, "and there's crass there that wat make them

as fat as putter."

"Od, Mr. M'Craw," said Mr. Jack, "the only

thing I ken o' Tyree is that it's fu' o' witches. But without

ony jokes, I have seen some fine fat beasts frae that island."

"Who toes Tyree pelong to?" asked Mr. Cameron

in a defiant tone.

"To His Crace the Chuke of Argyle," answered

M'Craw proudly, "the creat M'Calein More."

"The whole o' Lochaber pelonged to the Tuke

of Gordon, who was a petter man than ever a Tuke of Argyle was;"

and the irascible Mr. Cameron struck his fist on the table. -

This was too much for the defender of the

Duke of Argyle, who no doubt would have been very proud of his

champion if he had seen his face, and heard the tone in which he

replied.

"Mr. Cameron, His Crace the Chuke of Argyle

has peen a chuke pefore the Chuke of Gordon was fit for a

cateran, and M'Calein More never turned his pack upon a friend

or a foe."

The Duke of Gordon's champion was dumb with

rage and astonishment, and there is no saying what he would have

done, had not Scoodarach, who encouraged his companions to

quarrel to the very verge of flying at one another's throats,

and then by a few well-chosen words, made them greater friends

than ever, taken up the matter. "The Chuke of Argyle," said that

individual, "is a creat man, and the Chuke of Cordon was a creat

man—that is the tifference petween them; and it is much pity

that there is that same tifference, for the Marquis of Huntly

was an honour to Lochaber and to Scotland when he was at the

head of the Plack Watch, and let them to dory wherever it was to

pe found. Put he has cone to his home, and peace pe with him.

Your father, Mr. Cameron, and mines too, had many a hard fight

with him, and well, well they liked to talk apout him."

Even M'Craw was touched with the devotion

with which Scoodarach spoke of the last of the Gordon dukes, who

was evidently known by name to, and popular with the whole

party.

"Put what made ye say, Mr. Chaik," put in Mr.

Finlay, "that Tyree was full o' witches !"

"I'm thinking," answered that gentleman, "Mr.

M'Craw can tell ye mair on that subject than I can, for if a'

tales be true, there's no lang since he was afore the shirra for

callin' an auld wife a witch. Is it true that ye were fined

for't, man?"

"It was a wee fine," said M'Craw, looking

conscious; "and it wasna for calling her a witch, put for no

appearing at the Court when my name was called."

"It was aboot that cheatery wark o' the

stanes coming in through the roof o' the hoose, was it no?"

"Whist, Mr. Chaik, I ton't like to hear ye

talk that way."

"Do ye mean to say that there was onything

uncanny aboot it?" said Mr. Jack. "Tell us it, man; tell us it."

"Well, it's no a long story, and I 'll pe

willing to tell it"

All at table leaned forward with much

curiosity, and some awe was depicted in every face, and as the

narrative proceeded, even Mr. Jack was considerably influenced

by the bearing of his friends, and looked somewhat scared.

"The thing happened at Callum Du's house. He

was a tacent man, and had a wife and eleven childer, and what

with fishing and making the most o' his pit croft, they were

toing as well as their neighpours, and hadn't to make their

tinner of shell-fish gathered on the shore and poiled in the

brochan more than five times in the week. One tay the whole of

himself and his family and wife and pairns were in at their

tinner, and a crap which one o' the pairns had picked up at the

shore was fished out of the pot, and two of the pairns were

quarrelling apout it, when a roun' stone cam in at the top of

the house, without leaving a hole aifter it, and came thack

town, and struck the crap out o' their hands on the floor.

Callum was so pusy at his brochan, that he tidn't notice the

pairns till he heard them give a roar. He then looked, chust as

a wee pit balachan, two years old, was going to pick up the

crap, and what should he see?"

Here the narrator's voice sank to a sort of

whisper, and his lips became parched, and so unmanageable that

he could scarcely bring them to subjection so as to perform

their functions. The rest partook of his emotion, and several

asked in the same tone, "w/iatf?" " The crap," continued M'Craw,

"moving slowly away from the laddy, although it was well poiled,

and had no more life in it than the herring I eat to my tinner

to-tay. Callum and his wife and the grown-up childer were tumb

with fear, put the wee laddy laughed and went aifter the crap,

till his mother got hold of him and kept him pack. Then another

pairn went to the pot, with a spoon to get some out of it, and

the pot moved off aifter the crap, and another stone came in at

the top of the house, and it tidn't left a hole aifter it

neither. The whole of them then ran out of the house, making a

noise that prought aal their neipours apout them, put none of

them wat go into the house, till Tonalt Tawlor came, and he said

he wat go in. Put if he tid, he tidn't remain long, for water

came pouring town upon him, and pefore he could get out he was

more like a trooket fox than a Christian. No one wat go in after

this, and some one went for a chustice-peace, and he came next

tay, and went in quite pold and sat town. He soon heard splash

splash on the loft, and up the ladder he went, to a smaal place

where there was two peds, and he found one of the peds full of

milk, and the other of water. Well, he went town again and

called Callum in, and though feared he tidn't like to refuse the

chentleman, and went. ' Pretty pusiness this, Callum,' says he,

' to put water in one ped and milk in the other. If you attempt

to cheat me, I 'll have you put in chail.' ' Och,' cried Callum,

' it's me that's no cheating, as God's my wutness.' 'The tevil

is more likely to pe your wutness,' said the chustice, very

angry, put he no sooner said so than the pot pegan to move. When

he saw this, he looked with his eyes very open, put he was pold

enough, and said, ' This is one of your tricks,' and with that

he went to the pot, put he couldn't get near it, for it kept

tancing round him till he got afeard, and walked out of the

house, and without saying one wort he chumped on his horse and

galloped away. I happened to pe in the island at the time, and I

went to see if it was aal true I heard."

"And what seed ye, man?" said Mr. Jack, whose

leathern jaws lengthened, though long enough before, during the

recital of this astonishing story.

M'Craw resumed, "I saw the pot, for I went

into the house, and when I was looking at it, a hard peat came

in at the side of the house where there was neither toor nor

window, and struck my pack, and made me chump till I nearly

prained my head akainst a peam. When I looked round at the pot,

as I was going out at the toor, for I tidn't remain longer in

the unplest place it was tancing round the kitchen."

"Did ye see that wi' your ain een?" asked Mr.

Jack.

"Yes, Mr. Chaik, I saw it with my two plessed

eyes."

"Then," said Mr. Jack solemnly, "there is

mair nor guide graiss grows in Tyree, or I am mista'en."

The party became very sombre after this, and

I dozed into an uncomfortable state of unconsciousness for some

time. I was roused out of this by something tumbling over me,

which turned out to be the fiery Mr. Cameron, who was going on

deck, and was hurled upon me by the labouring of the steamer,

which was straining and creaking in every timber. His temper was

by no means improved by his contact with me, and he started up

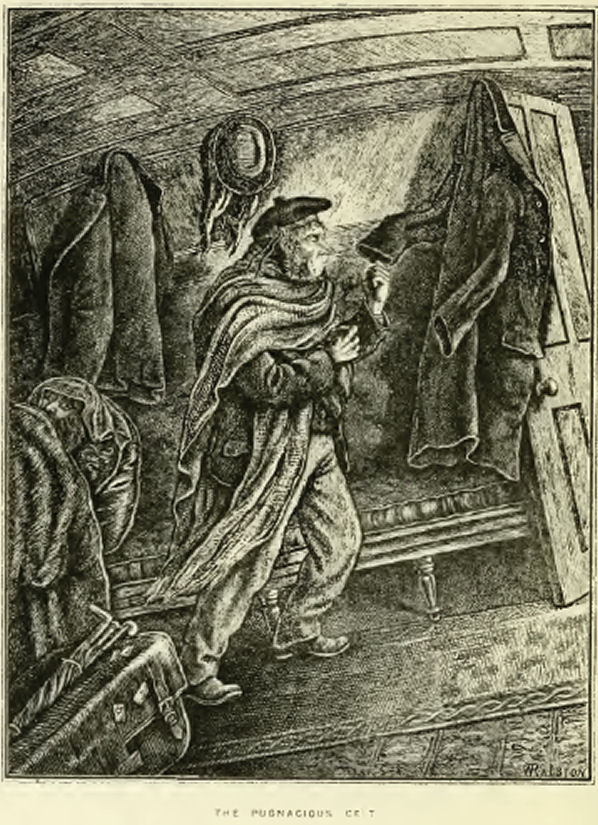

as if mortally insulted, and made for the door. It happened to

be open, and a large top-coat was thrown upon it which hung down

more than half way to the floor, and might be mistaken, by a

person who had been imbibing "Talisker" and "Long John' for four

or five hours, for a man. The boat tossing violently made the

arms of the coat swing in a bellicose way that at once attracted

the attention of the pugnacious Celt, who steadied himself for a

moment, and then made a rush at it with very hostile intentions.

The shock of the collision was considerable, and Mr. Cameron was

thrown back rolling under the table, carrying the coat with him,

which he pummelled most unmercifully, and refused to let go when

the steward and others came to the scene of action, until it

should own itself vanquished. The last I saw of Mr. Cameron was

his being carried, kicking and scratching frantically, up the

cabin stair; and when the steward returned his shirt collar had

disappeared, and one of his sleeves dangled gracefully about his

arm. After this the party did not muster. The tumblers, however,

were empty, so that there was no liquor thrown away. How they

stowed themselves away for the night I do not know, further than

that I heard terrific snoring in all directions, from which I

infer that they enjoyed more sound and undisturbed slumbers than

fell to my lot.

But I did sleep too—a troubled,

uncomfortable, unrefresh-ing sleep—and when I awoke in the

morning, daylight was struggling in at the little round port

holes. I heard a friendly chat going on not far from me, and

listened.

"Chust a smaal trop, Mr. Finlay, to open your

eyes, aifter being aal night on the Moil. It's a pad place the

Moil, and many's the goot man that found a sore head there."

"Your health, Scoodarach," answered Mr.

Finlay, and soon after I heard a smack of satisfaction. "Now, ye

'll tak a taste yourself, for what has done me so much goot

cannot to ye harm."

"I have been tasting with Glenbogary when he

took his morning, but I will trink your health for luck, Mr.

Finlay;" and he did so in a bumper of pure whisky. He noticed

that I was awake, and immediately came to me.

"Ye 're petter now, sir," said Scoodarach

cheerfully, "and to put aal right ye 'll take a smaal trap out

of my pottle. We 'll soon pe in Oban, for Kerrera is showing its

nose to us, and the 'Arap' is going her pest" I thanked him, and

declined the whisky, to his no small astonishment "Perhaps ye

would like prandy or wine petter." I assured him I could not

taste either; upon which he looked at me compassionately, and

said,

"Hoo! I see now,—that's why ye were sick last

night." The steamer was soon all alive, and shortly before

reaching Oban, breakfast was served, and most of the boon

companions of the night before sat down to it with as keen

appetites and as hearty as if they had gone to bed sober at nine

o'clock instead of "very fu'" at two in the morning, I did not

breakfast until I went on shore at Oban, and I confess I thought

it a very pleasant change. I determined, however, to go to the

quay as the "Arab" was leaving, to have a last look at the tar

barrels, and at the drouthy Scoodarach perhaps; and to be sure

there they were, and Glenbogary's broad hat and broad coat-tail

nodding and fluttering in the breeze. He was telling something

to a stranger who listened in seeming wonder and admiration.

What it was I can only conjecture. I was nearly knocked down by

some one pushing violently past me, and on turning round I saw

two men rushing along the quay, who I thought had been left

behind, but I was wrong in this conjecture. The one got hold of

the other by the arm, the better to direct his eyes, and

pointing in a very excited manner at the retreating steamer,

said, "That's him that sold the two queys for forty poundsI"

"And fifty the next day," I repeated, as I

walked away to the Caledonian. "But the queys was goot!"

|