|

A CITY OF LIGHT-A GAS AND OIL FIGHT-A HINT FOR GREENOCK-CHICAGO-CATTLE

GRAZING ON A LARGE SCALE-THE NOBLE INDIAN-IN THE MORMON COUNTRY -OGDEN-A

RIDE ON THE UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD- AMONG THE MORMONS-THE FINEST CITY OF

MODERN TIMES-SALT LAKE CITY-A HINT FOR PLANNING MODERN PUBLIC

BUILDINGS-SURROUNDING LOCALITY, WHAT IT WAS AND WHAT IT IS.

OUR next journey was to the City of Akron, in the State of Ohio, a busy,

thriving community of about 20,000 inhabitants. The Akronites are a

go-a-head people, and don't stick at trifles; have their eyes open for all

improvements, and the brains to take advantage of them. A gas company had

the lighting of the city, but the Corporation and the public were not

satisfied with the prices charged, so they got discontented with their gas

company for charging too much, and the Corporation hung the city with oil

lamps, and lamps and gas burned lovingly side by side for several nights,

to the great satisfaction and enlightenment of the inhabitants. The gas

company were beat, the lamps were victorious; but dull oil did not suit

the tastes of the Akronites; they went in, head over heels, for the

electric light, and got it too; and when all the lights are fixed up,

Akron will be a city of light—not a light hid under a bushel, but a blaze

of light in the midst of darkness.

The city stands on about two square miles, and two lights are already

erected. One of the two is placed on an iron pillar of huge proportions;

it is about two feet in diameter at the base, erected on a strong, solid

foundation, and rises to the great height of 220 feet above the surface of

the ground. The spire of the Mid Church in Greenock is about 16o feet or

thereabouts, an estimate can thus be formed of the height of this huge

iron pole. The other light is placed on a tall wooden mast fixed on the

top of the College—for Akron boasts of a College also— and these two

lights illuminate a large section of the city. We could read newspaper

print with the greatest ease at a considerable distance—say as far as from

the railway station to Cathcart Square, or about 300 yards from the light.

When the eight lights are in full operation, Akron will be the best

lighted of all cities. It is asserted that the electric light will be as

cheap, if not cheaper, than gas, and water power not being handy, the

electric machinery is driven by steam power.

Sir William Thomson recently pointed out Greenock as the most favourably

situated town in regard to water power being applied for lighting by

electricity. In the recent report by Mr James Wilson, C. E., of the Water

Trust, the same idea is ventilated, and as deputations have become so

common of late, a deputation of the Police Board might be despatched to

Akron to look about them, and on their return report on what they saw! The

deputation would enjoy the trip; whether the ratepayers would, is another

question.

Akron is a most energetic, thriving, busy city. We visited a very large

work, the Buckeye Agricultural Implement Manufactory. At the time of our

visit they were manufacturing one hundred and five reaping machines daily,

and sending out daily one hundred and thirty, thus reducing the stock they

had accumulated during the winter months. The same company have another

work equal in extent, and doing as much business, in another city. All the

labour in these manufactories is done by the piece, and the workers make

good wages. We also went over an extensive carriage factory, in which the

average weekly out-put of "buggies" ranges about thirty. One marvels much

where they all go to, and who buys them.

We left this city of light for Cleveland, from where, the same night, we

took the steamer and crossed Lake Erie for Detroit. Arriving there the

following morning, we went straight on to Pontiac, about thirty-five miles

distant, and then proceeded to the residence of my apprentice master, who

had for a considerable time carried on business in Greenock as a

contractor, and though it was over thirty years since he left, we still

continued to keep up a friendly correspondence, and to visit him was one

of the objects I had in view when I left Scotland.

I remembered that he used to have a great antipathy to book canvassers and

pedlars. When any of these entered his premises, if he was present they

were very soon shown the way to the door, so I arranged with my travelling

companion that he was to keep a little behind while I introduced myself to

my friend as a pedlar.

He met me at the door, and asked me to enter. His features were little

changed from what they were thirty years ago, with the exception that his

hair was now white. Seeing him so little altered, I imagined that it was

the same with myself, and that he would at once recognise me. However, in

that I was mistaken. I produced a pair of spectacles, which I offered for

sale, saying that he would find them a decided improvement to anything he

had been in the habit of using, as they would have a tendency to renew his

youth, and bring former days to his recollection. He now became as

obstinate with me as he used to be with the pedlars. He would neither

listen to me nor would he look at my spectacles, but began to denounce all

hawked goods as trash, and took out of his pocket the pair he was using,

and said he had lately bought these in Detroit for a quarter of a dollar,

and he would defy me to produce as cheap and as good a pair out of my

whole pack. I tried them, and said they were very good, but mine were a

great deal better, and if after trying them he did not admit that it was

so, I would make him a present of them. At last he put them on, and I

handed him my card, saying that, as it was small print, it would be a good

test. Looking at the name, he exclaimed, "What is this ?" Looking again,

he says, "Greenock !" then looking at me, he said, "You are not the man

named here." I assured him that I was. He said, " No, no, that cannot be."

Re-asserting that I was no other, he walked out of the room, and instantly

returned, and, standing at a distance, he eyed me from top to toe as if he

had been taking my measure, at the same time saying, "You may have got my

address from him, but one thing is certain, you are not the man whose name

is on this card."

I then related to him several incidents of our former days, all of which

he remembered and admitted to be perfectly correct, but still he had

doubts as to my identity. While this was going on, I could not help saying

to myself—May not the Claimant have been the right man after all? All this

time we were standing; my friend now asked me to be seated, and brought in

my companion and introduced us to his good lady and granddaughter, and

made all haste to get his horse and buggy ready to go for our baggage.

The knowledge I had of his personal affairs in former times enabled me to

dispel all doubt as to my identity, and the greater portion of the next

few days was spent in answering questions, and relating the many changes

and important events that had taken place in Greenock during the past

thirty years, which appeared to be much appreciated by my old friend. He

occupied a nice cottage about a mile distant from the town of Pontiac. The

plot on which it is built is bounded at the back by a mill pond, in which

there is a plentiful supply of fish and small turtle, which we frequently

saw basking in the sun on a little eminence in the centre of the pond.

Beyond this pond was a marsh, from which came a variety of sounds—some as

if from a wild bull, while others were hoarse and short, as if you had

struck a coarse table bell and instantly put your hand on it and stopped

the sound. We were told that it was the cry of the bull-frogs. We went

down several times, but could never see them. We were anxious to see the

little animal that could send forth such a volume of sound. Pontiac, which

is in the State of Michigan, is a busy market town where farmers come to

make purchases and dispose of their produce. In the main streets there is

a row of stakes from six to eight feet apart, and about five feet high,

extending along the kerb on both sides of the street. These are common to

any one to tie up his horse while he attends either church or market. My

companion often gave free expression to his feelings on the cruelty of the

people in leaving their horses so long exposed under a scorching sun.

Our friend was much delighted in pointing out to us everything in which he

knew they were ahead of us in the old country. A day was set apart for

visiting places of interest, among which was the Michigan State Asylum for

the Insane, which is a very imposing structure situated about three miles

distant from Pontiac. In the portion of the building that is completed

there are over three hundred patients, so that the Americans, along with

all the good things they enjoy, have a pretty fair share of lunatics

amongst them.

Our friend having considerable experience of the delay, expense and

annoyance connected with purchasing or transferring a piece of land at

home, was anxious that we should accompany him to the Government Land

Agent's Office and to the Registration Office, where we would see the

expeditious, simple and economical method of transacting business as

practised by the Yankees.

On a previous occasion, while in 'Toronto, I had an opportunity of

witnessing how expeditiously a land transaction there can be completed. I

accompanied Mr Smith, who went to take off a new township (which, if I

remember right, is ten miles square) of forest land, to clear it of the

growing timber. The object of our visit was stated. The agent produced the

map, pointed out the limits, stated the terms, and the transaction was

completed with as little delay or ceremony as we would have here in

purchasing a barrel of flour.

At the Register Office the books were produced, and we were shown the

various stages through which several plots of ground had passed from the

original purchase through a number of transfers, with mortgages and

searches, some of which had been done without the assistance of an agent.

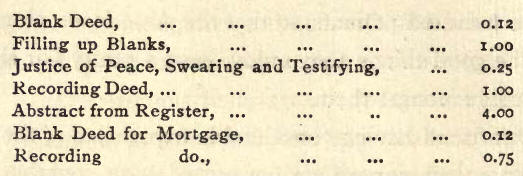

The following is what was given to us as the items of expense :-

The whole amount for title deed, mortgage and registration is seven

dollars twenty-four cents, being under thirty shillings of our money—a

mere fraction of what it would cost for similar documents at home.

It was during our stay here that the attack was made on the life of the

President; the sad event caused great excitement, people driving in from

the country to get the latest particulars. The morning following the

dastardly attempt we were awoke about one o'clock by loud knocking at the

door: this was one of the neighbours with the latest news, to the effect

that there was still hope of the President's life.

Much to our regret, we had to make our stay short, and, parting with our

old friend, we returned to Detroit and purchased railway coupons right on

to San Francisco, taking the first train to Chicago, where we spent only

two hours, as we intended spending a few days there on our return.

For many miles after leaving Chicago the fields are covered with various

kinds of crops, but as we proceeded on our journey the principal crop

grown is Indian corn. Orchards are plentiful, and occasionally vineyards

were visible.

We arrived at Omaha, thus completing a third of our long journey in

comfort and safety, and having stopped to change carriages, we travelled

onwards. In a short time we gradually got into the midst of immense fields

where cattle were seen grazing in thousands. The herdsmen are all mounted,

and in several instances they had the cattle gathered in large groups, but

for what object we could not learn. As seen in the distance the group of

cattle reminded one of a fox-cover in Renfrewshire, the mounted herdsmen,

the sportsmen round the cover and the stray dogs outside, kept up the

resemblance. In some cases, where the cattle were not so closely tended by

the herdsmen, and a stream or pool of water near, the cattle were to be

seen standing in the water, nothing visible of them but their backs and

heads, and seeming to enjoy their cold bath.

Along the railroad were to be seen great numbers of prairie chickens and

huge butterflies, some of them of most beautiful colours. We were now

running along the level prairie lands, where there was nothing to break

the monotony of the view save a solitary tree now and then, or perhaps a

farm hut away in the distance, reminding one of the ocean with a ship

appearing occasionally on the horizon.

There are many villages along the line where the trains stop, some of

which are kept up by the railway company,

and at most of them there is a refreshment room or dining saloon, which is

generally attended by black waiters. In some instances the blacks had

given place to Chinese waiters, and everything in the shape of refreshment

is served expeditiously, and on the shortest notice. At some of the

stations there were to be seen Indians with their families—a wretched,

dirty lot, quite different from the "noble red Indian" of the novelist.

They did not beg, but merely sat in their dignity and dirt, and looked on.

Some of their children, who had bows and arrows, were kept very busy by

the passengers placing a coin on a peg, when the boy who struck it off

with his arrow claimed it. At this work, the boys, who were from eight to

ten years old, were remarkably clever, and the certainty of their shooting

quite astonished the onlookers, The Indian dwellings were situated outside

of the villages. They are called "dug-outs." The roofs of them were very

like the potato pits on a Scotch farm.

At Larmie city we came across what was to us a singular spectacle. It was

a train decked out in mourning. Some of the carriages had three huge black

and white rosettes placed on each side of them, and black and white

pennants and festoons hung from the roof on each side of the rosettes.

This strange mourning display was said to be on the occasion of the death

of one of the "conductors" of the line.

We were now far beyond the bounds of civilisation, save what was clustered

in the villages along the line. The bones, white and bleached, of numerous

cattle that had died, lay on each side of the rails. They lay in clusters

here and there—some fresh looking, as if the animals had died but this

season, and others as if they had lain for years.

We had traversed a great distance of level and undulating prairie land.

Each little village along the line seemed the outposts of civilized life;

and in the future this vast expanse will probably be a cattle-rearing,

grain-growing country, whose surplus products will be carried by railway

to the seaboard for shipment to other countries.

This Union Pacific Railroad is a great undertaking—a mighty agent in

colonising and developing the vast resources of the lands through which it

runs, and every year adds to the population, wealth, and trade of this

portion of the United States.

Having been now two days on the train after leaving Omaha, and running a

distance of about 940 miles, and 7,500 feet above the sea level, we passed

from the territory of Wyoming into Utah. About twenty miles further on we

arrived at Evanston, where the train stopped half-an-hour. This is. a

thriving village, with about 2,000 inhabitants, where there are extensive

sawmills and coal mines. The Railway Company own some of the mines, and

also extensive engineering workshops, which employ a number of inhabitants

all the year round. This station was very much admired by the passengers,

most of whom dined at the Mountain Trout Hotel, where they were very

expeditiously served by Chinese waiters, who were all dressed in their

native costume, and wore their "ques." They all spoke good English, were

very polite, attentive, and anxious to give information to all who asked

it. The Chinese have a settlement here, with their Joss-house and other

native attractions. On leaving the dining-room, our curiosity was excited

by a number of Indians who had come upon the scene, with their children,

some of them very gaudily dressed with shining trinkets, furs, and

feathers, and their faces daubed over with red paint. They did not beg,

but there was a vacant stare in their countenances which told its own

tale; when anything was offered them, they took it as if with reluctance,

and turned their faces away, putting one very much in mind of the look of

a dog to which you had offered a large piece of bread.

While the train was stopped at one of the stations, a gaudily-dressed,

tall, masculine-looking female Indian took up a position on the platform

of our car. In her hand she carried a fine little tomahawk, very highly

polished, and the handle decorated with rings and round- headed brass

tacks. One was driven into the end of the handle, fixing a rosette of

various coloured ribbons. The weapon seemed more ornamental than useful.

When spoken to she did not answer. She was handed a coin, and asked if she

could speak English, but she gave no symptoms of hearing, when one

remarked that she was perhaps a dummy. The engine-driver, who had been

looking on, said if we gave her two or three glasses of whisky we would

very soon hear her speak English like a politician. He said the greater

number of the Indians who frequented the stations pretended they had no

English until they get drunk, and then they could speak English very well.

The Railway Company on this line allow the Indians to travel free upon all

freight trains, so that it is quite common to see Indians and their

families perched on the top of a truck of goods or in cattle trucks. Some

of them travelled short distances by our train, but did not mix with the

passengers. They kept on the platform outside. It is said that the Railway

Company have got the Indians under the impression that they only have the

right to ride free, because the railway belongs to them. Under this

impression, they do their utmost to protect the line from being injured.

It is well for the safety of the trains that the Indians should remain in

that belief —were they to take up a position antagonistic to the railway,

the consequences might be serious for both the Railway Company and the

passengers.

From this point on to Ogden is about eighty miles, the line having a

gradual fall of over 3,200 feet. This is the grandest, though the wildest

and most dangerous, part of the journey. It is difficult to say whether

there is most danger from the treacherous-looking narrow ledges, deep

chasms, and sudden turns that the train has to follow along the margin of

the Weber River, or from the shattered overhanging mountains which you

imagine the vibration of the train would set in motion at any point. The

close proximity of the mountains above and the rapid flowing of the river

beneath give an apparent velocity to the train that is terrific. This

feeling is intensified by the rushing sound of the train and the steam

whistle, the echo of which is heard overhead reverberating from cliff to

cliff as if you were in the midst of a thunder storm. Here the curves of

the line are so sharp that the passengers in the front carriage are for a

moment just within speaking- distance of those in the last carriage, when

all of a sudden the front carriages turn in the opposite direction, and

the train, which is over seven hundred feet long, assumes the form of the

letter S. This exciting scene continues for more than thirty miles, until

we pass the Devil's Gate and Slide, where we emerge into the open country

where cultivation is carried to great perfection by the Mormon settlers.

In a short time we arrive at Ogden City, where all have to change

carriages, this being the western terminus of the Union Pacific and the

eastern terminus of the Central Pacific Railway.

After an hour's delay, we take the train on the Utah Central Railroad to

Salt Lake City—distance, thirty-two miles. The fare is about threepence

per mile, and it is one of the best paying lines in the States. This

railroad was one of the enterprises of Brigham Young. When the Union and

Central Pacific Railroads were completed they met near Ogden, their

combined length being 1,914 miles. Necessarily a great deal of material

was left over, which was purchased and used in the construction of this

line, which is thirty-two miles in length from Ogden to Salt Lake City, it

being completed within nine months from the time the ground was broken.

There was little cutting or filling up required, as it passed through a

level track of country from five to six miles broad, having the Salt Lake

within a mile and a-half on the right and a mountain range about four

miles to the left.

There are several stations and villages along the line, the inhabitants of

which are chiefly employed in agricultural pursuits. Arriving at Salt Lake

City, and taking a run over it, we came to the conclusion that, with one

exception, it was the finest city that we had yet visited, the streets

being 130 feet wide, all set off at right angles and at such a distance

from each other as to give ten acres to each building block. Some of these

blocks are again sub-divided into four building plots, and those in the

workmen's district are again sub-divided into eight building plots, giving

one and a quarter acres to each plot. The ground is generally used as an

orchard, and the houses are all placed back at a uniform distance from the

line of the street, so that there are invariably fruit trees between the

streets and the houses. Four of these blocks, containing over forty acres,

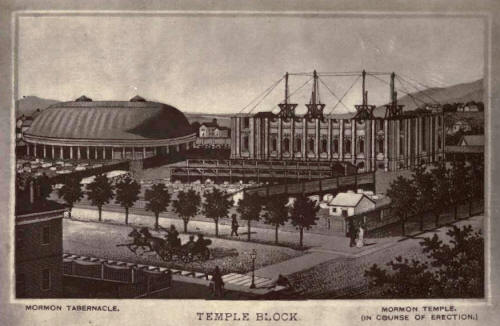

are walled in and set apart for religious institutions. On one of these

plots stands the Tabernacle, a large, rough-looking building, about two

hundred and sixty feet long by one hundred and fifty feet wide and eighty

feet high, with semi-circular ends, and covered with a dome roof,

supported on a succession of stone abutments, each about ten feet broad

and three feet thick.

The thickness of these abutments and the spaces between them, all of which

are doors, form the exterior of the building. The breadth of the abutments

runs in towards the centre of the building and forms the support for the

back of the gallery, which is carried round the two sides and one end. At

the other end is a platform, whereon the grand organ is placed, on each

side of which are the seats for the choir, which numbers about four

hundred voices—the one side being occupied by females and the other by

males.

In a line right in front of the organ there are three pulpits, each being

at a lower elevation as they recede from it. Elevated a little above the

area beneath the third pulpit is the elders' bench. On each side of the

pulpits are seats for those who take an active part in Church matters, and

who occasionally address the audience. In the area there is a passage all

round next to the external walls. Other three passages run the whole

length of the area. In the middle passage, and right in the centre of the

building, there is a grand ornamental fountain, from which, during service

in summer months, there is a flow of iced water. In the roof there are

several cupolas, and the ceiling is a complete network of festoons, formed

of evergreens and flowers. Each panel on the front of the gallery has a

shield or ornamental design, in the centre of which a letter is placed.

These letters give the motto, "God Bless our Mountain Home."

Though there is accommodation in this building for thirteen thousand

people, yet there is never any crushing or inconvenience on entering or

leaving; those on each side of the centre passage walk along towards the

exterior, and a door faces them at whatever point they reach. Three

minutes are sufficient at any time to evacuate the whole building. The

Tabernacle is used for worship during the summer season only, it being too

large for artificial heating.

In the winter season the meetings are held in the assembly hall, which is

a beautiful granite building erected on the temple block alongside of the

Tabernacle. It has a centre tower, two spires and a great many minerets,

is heated by steam, lighted with gas, and has a grand organ, and is seated

to hold about three thousand people. On the east of the same block a

temple on a grand scale is at present in course of erection. The mason

work is about forty feet above the surface. Judging from what is already

done, this promises to be the most substantial and picturesque building in

the city.

On the occasion of our visit, had we not known that we were in the Mormon

Tabernacle, we could not have observed the difference from a Presbyterian

Church by either the rendering of the service or the matter of the

discourses, which, after the usual prayer and praise, were delivered by an

occasional layman, who left his pew and ascended one of the pulpits. At

the close of the service the President stated that since his last

intimation eighty- one thousand dollars had been subscribed towards the

erection of the new temple, and there were now only five thousand more

required for its completion. There was no money collected at either of the

diets.

There is a general impression that Salt Lake City is inhabited by Mormons

only. Such is not the case now, though it was so at first. It is said that

there are twenty-one thousand Mormons and about seven thousand Gentiles,

who are of various religious denominations. The Methodists, Episcopalians,

and the Presbyterians have each their places of worship in the city.

After dinner, we resolved to have a view of the city and its surroundings

from Ensign Peak, that being the mountain at the base of which the city is

situated. Shortly after starting, we had a friendly chat with one of the

settlers, to whom we made known our intention. He asked how long we

expected it would take. On telling him, he advised us to go no further,

assuring us that the distance was three times what we anticipated, and it

would probably be dark before we reached the peak. We took the hint and

postponed our trip till the following day, when we set out a-new, and long

before arriving at the summit, we found we were much indebted to our

adviser of the previous evening, and were forced to the belief that our

vision as to distance was much more deceptive than usual, which defect we

attributed to the rarified atmosphere and elevated position of the

country.

Ascending towards the peak, the ground was literally teeming with animal

life, of which every step gave an indication, by the efforts of numerous

insects springing to the side as if to make way for us, conspicuous

amongst them being the grasshopper, but very different from those we are

accustomed to at home. Some of them were larger than the humming bird,

their flight seldom exceeding more than from thirty to forty yards. We

made several unsuccessful attempts to capture one, but, whenever we came

within reach, it took a spring and repeated its flight with as much vigour

as before, so we gave UI) the chase. There were indications of an old cart

road a long way up the steep incline. This somewhat puzzled us, until we

observed at various places little artificial mounds, one of them within a

few yards of the summit. These had been thrown up by the original settlers

when exploring the mountains for gold. The cart track referred to was that

along which the workmen conveyed their implements as far up hill as that

mode of conveyance would permit. No mineral having been found of

sufficient value to remunerate the miner, Ensign Peak has been spared the

indignity of being subjected to disfiguring operations, and is now likely

to be left alone in its natural beauty.

Fatigued and out of wind, we arrived at the summit, and were amply

rewarded for our labour in the magnificent and impressive scenery that lay

stretched out before us. A little to the left, and apparently at our feet,

stood the city, which is about three miles square, the ponderous

Tabernacle and the half-built temple forming prominent features in the

foreground. At the base of the mountain, and just in front of us, is the

plain through which we had passed on arrival, beyond which is the green

marsh land receding in the distance till it merges into the Salt Lake,

whose water is seen reflecting, like a vast mirror, the different objects

on its shores. To the left, and beyond the city, is the rich valley of the

Jordan, covered with crops and studded with farm-houses, which seem like

specks in the distance, and ultimately are lost to view before reaching

the base of the mountains which enclose the valley on each side.

Some of the deep gorges and fissures on these bleak mountain sides are

covered with snow, giving them a pleasant variegated appearance, in

beautiful contrast to the alternately green and yellow fields in the

plains beneath. The dissolving snow forming little streamlets, trickles

down the slopes which, in former times, found their way through the barren

plain into the Jordan, leaving little streaks of verdure along their

course. What a contrast is the present scene with the past!

Thirty-four years ago, the evicted Mormons came upon the scene, claimed

this desert as their home, and with firm resolution and willing hands

turned Nature's stores to their own purposes. Having fixed on a pite for

their city, they set to work to form ponds in the creeks, and to cut a

canal along the sides of the mountains, intercepting the streamlets a

little way above the plain, and leading the water to such points as were

most advantageous for the irrigation of the plain. Descending from the

peak, we stood for a little on the bank of the canal right over the city,

and contrasted the barren sage- covered land above with the gardens and

orchards of the city beneath and the rich, fertile fields beyond, and had

to confess that whatever may have been the faults or failings of the

Mormon settlers, the scene before us showed an amount of industry and

perseverance that it is doubtful if it can be equalled anywhere else. They

have, in very truth, made the "wilderness to bud and blossom as the rose."

From this point we descended into the city, and had a pleasant stroll

through the streets, where we found much to engage our attention. From the

canal we had just left there was a stream of water flowing down on both

sides of each Street. The channel-ways for this water were about eighteen

inches wide, nine inches deep, and formed of wood, with little sluices at

points suitable for diverting part of the water into the gardens; its

chief use being for irrigation and flushing of gutters, the domestic

supply being brought in iron pipes from the water works at City Creek

Canon, which is at such an elevation as gives sufficient pressure for

extinguishing fires, and for that purpose there are stand-up hydrants

placed at short distances along the sideways.

To these hydrants are attached the hose for watering the carriage-ways,

which, during the summer months, is done every day except Sunday, this

being part of the duty of the men of the fire brigade. Outside of each

footpath, between the water course and carriage-way, there is a fine row

of shade trees, while on the other side of the footpaths the trees of the

orchards overhang the pathway, forming a pleasant, cool, shaded grove to

walk under—the pleasure being much enhanced by an abundance of flowers,

and all kinds of fruit overhead, quite within arm's-reach, and in many

cases considerable quantities lying on the footpaths. None of the citizens

are tempted to pull them, as everyone has an orchard of his own, in which

there are apples, pears, cherries, peaches, apricots, grapes, &c. Every

kind of fruit seems to grow to perfection, except the gooseberry, which is

very small, hard, and covered with small thorns.

Tramway cars are run in every direction from the centre of the city to

nearly three miles distant, the driver acting the part of guard. The cars

are drawn by mules, each of which is branded with the letter Y, the latter

being at one time the property of Brigham Young.

Not having observed any policemen in our rambles, we inquired how it

was—if they were dressed in plain clothes? We were informed that there was

no such official required; that the city was divided into wards, and each

ward had a surveyor or master who attended to its interests, and intimated

to the inhabitants when their labour was required to carry out any public

improvement. There was no evading this intimation; each had to turn out or

send a substitute, and had at all times to take the responsibility of

protecting his own property. Our informant stated that formerly they had

neither lawyers nor publicans, but now that a great many Gentiles had

settled amongst them, both these occupations had got a footing.

|