|

“God gives to

every man

The virtue, temper, understanding, taste,

That lifts him into life, and lets him fall

Just in the niche he was ordained to fill.”

WILLIAM

COWPER.

IN early Saxon

times the smith was ever regarded as a mighty man. “His person was protected

by a double penalty. He was treated as an officer of the highest rank, and

awarded the first place in precedency. After him ranked the maker of mead,

and then the physician. In the royal court of Wales he sat in the great hall

with the king and queen, next to the domestic chaplain.”

From his great

skill in handicrafts, especially in all kinds of iron-work, Alexander Mackay

soon became as much esteemed by King Mtesa and his court as the early smith

was by our woad-stained ancestors. Miscellaneous articles were showered upon

him to repair, and much wonder expressed at the burnished face he put on

metal goods. The native smiths could manufacture hoes and hatchets, also

steely knife blades, but the art of tempering was unknown. To

Burogo (witchcraft) the natives attributed the process by which he put

hardness into steel and took it out again. Neither had they any idea of

rotatory motion, and when he rolled some logs up an inclined plane, he was

followed by dense crowds calling out, “Makay lubare! Makay lubare dala!”

(Mackay is the great spirit: he is truly the great spirit.)

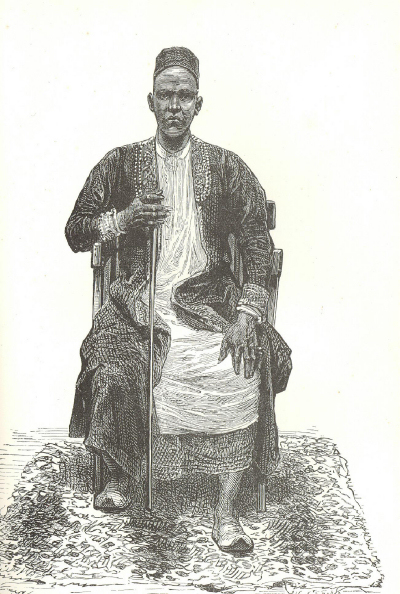

King Mtesa

See

“Industrial Biography-Iron Workers and Tool Makers,” by Dr. Samuel Smiles.

Mtesa was very

intelligent, and could understand anything if properly explained to him.

Mackay told him about railways and steamers: how seventy years ago there

were no railways, and now the world is girdled with a network of them. He

entertained his majesty with accounts of the telegraph and the telephone and

the phonograph, and greatly impressed him by saying, “My forefathers made

the WIND their slave; then they put WATER in the chain; next they enslaved

STEAM; but now the terrible LIGHTNING is the white man's slave, and a

capital one it is too!”

Another time

he gave the king and court a lesson on astronomy, illustrating it with

Reynolds' beautiful diagrams. They very quickly understood the first

principles of the Cosmos. Many Arabs were present, and Mackay showed that it

would be impossible to fast a whole month, as the Koran ordered, in the

polar regions, where some months the sun never sets, and others he never

rises, adding, “Mohammed could not have been a true prophet of God, else he

would have known this. I am no prophet, and yet I know much more than he

did.”

On another

occasion he took Huxley's “Physiography” to the palace with him, to show the

circulation of the blood, etc. Such a subject proved intensely interesting.

He dwelt on the perfection of the human body, which no man could make, nor

all the men in the world; and yet the Arabs wished to buy a human being,

with an immortal soul, for a bit of soap! The argument went home, and the

king said, “From henceforth no slave shall be sold out of the country.”

Mackay told him that was “the best decree he had made in all his life.”

Being a layman

and having had much to do with large bodies of workmen, together with the

valuable experience he had acquired as a Normal School teacher, and being

besides a shrewd observer and independent thinker, he derived his knowledge

of men from real life and not from books. He cultivated the society of the

natives in order to win their love and friendship, joined them at their

meals of meat and plantains, which the Arabs scorned to do, respected their

prejudices as far as consistent with his conscience, invited many of them to

his own house (or rather hut), and entertained them with a magic lantern,

which he contrived to make a chimney for out of a couple of Huntley and

Palmer's old biscuit tins, one laid horizontally on the top of the other and

tacked vertically into a wooden box. These exhibitions greatly delighted the

people. Pictures of houses and details they could not understand, as they

had never seen any building beyond a grass hut; but the representations of

animals were much appreciated, especially when the exhibitor tried a little

phantasmagoric effect.

But all these

mechanical employments were subsidiary to the spiritual, and he never lost

an opportunity of introducing, in a happy way, the subject of religion, or

of dropping a word that would touch the heart.

In his

log-book in the early part of 1879 are many entries similar to the

following: “House inundated with small boys reading with me, and watching my

operations. They say my heart is good. I wish it were, and theirs also.”

“Chief who

brought the canoes from Busongora spent last night with me. Gave him one of

the white blankets off my bed. Had a long conversation with him on the way

of salvation. He has been taught something of Islam, but cares little for

that, and took a good deal of interest in what I told him last night.”

“Every day I

am learning to admire this people more and more.”

As he became

familiar with the language, however, he heard of many crying iniquities, -

“And oft his

wakeful hours were filled by grief and bitter sighs,

O'er cruel deaths, revengeful blows, and slaves' heartrending cries.”

He never

shrank from exposing such evils to the king in open court, and privately to

the katikiro (prime minister and judge) and to the chiefs.

He writes: “It

is clearly my duty to point out their error and to show them a better way.

But great tact is necessary for this, and more wisdom than human. Yet I

believe that, with all my unworthiness, I have had more than once Divine

guidance and aid in such delicate work. Well I know that such sacred duties

could be many times better done than I can do them. But my Master above can

use even the humblest instrument in His own hand. The power is in Him

alone.”

Every Sunday

the flag was hoisted on the Palace hill, and Mackay held a short service and

read and explained the story of the Gospel, dwelling especially on the

blessedness of doers and not of hearers only. He invited free conversation

on the passage read, and great eagerness was shown by king and chiefs and

numerous youths to know and possess the truth. Sometimes Mtesa was so much

struck with the explanation of a parable, that he remarked to his people “Isa

(Jesus), was there ever anyone like Him?” It seemed as if the prophecy was

about to be fulfilled: “The kings shall shut their mouths at him; for that

which had not been told them shall they see, and that which they had not

heard shall they consider.”

In the

meantime two reinforcements to the mission were en route for Uganda.

The first arrived by the Nile, having ascended that river under the auspices

of General (then Colonel) Gordon. Unfortunately Egypt had always been an

object of great suspicion in the eyes of the Baganda. Captain Speke, who

formed Mtesa's acquaintance a dozen years before Stanley, tells how the king

objected to his passing through Uganda to Egypt via the Nile, and how

he only gave way on his promising to do his best to open a communication

with Europe by its channel! [See

“Lake Victoria: a Narrative of Exploration in Search or the Source of the

Nile, compiled from the Memoirs of Captains Speke and Grant.” By George C.

Swayne, M.A. (William Blackwood And Sons).

]

The Egyptian

station of Mruli was regarded by Mtesa with very jealous feelings, and the

Arabs lost no opportunity to fan the flame. Knowing well that with the

presence of the white man the hope of their gains was gone, they told him

that the “Nile party” were coming as political spies, and were really

emissaries from Colonel Gordon, and that the Turks (as they called the

Egyptians) would soon come and “eat the country.” Mackay saw that the king

was becoming very nervous as the time drew near for the arrival of the

expected missionaries. The Baganda had the word Baturki as often in

their mouths as ever the Romans had the word Carthago in the last

days of the empire. He (Mtesa) never wearied in narrating all his

intercourse with white men: how Speke brought Grant, and then sent Baker;

how Colonel Long came, and was followed by Stanley; and now when this party

comes there will be five white men in Uganda. What do they all want? Mackay

tried to assure him that “they were merely corning in response to his own

invitation, and that neither the Queen nor Colonel Gordon had sent them,

that godly men in London had asked them to come to teach him and his people,

etc.;” and then with tact he changed the subject to one he knew would

interest him. But in the middle of it Mtesa, in his abrupt way, asked, “Are

these fellows not coming to look for lakes, that they may put ships and guns

on them? Did not Speke come here by the Queen's orders for that purpose?”

At length, on

the 12th of February, 1879, the king received several Arabic letters from

the north, containing gossip about the new party and their stuff. The bearer

of the letters was also closely questioned about them, and in a tone of

relief Mtesa said to Mackay, “Their guns are only muzzle-loading.”

“Only soldiers

require breech-loading rifles, and our party are not soldiers.”

“Will they

bring gunpowder?”

“I don't

know.”

“Will they

bring beads?”

“Not likely.”

“What will

they bring?”

“I cannot

tell.”

The following

entries in his journal are interesting:-

“Friday,

Feb. 14th, 1879. - Early my friends arrived. …..In afternoon I was

summoned by Mtesa to give an account of my brethren. Arranged with him that

we should all come up to-morrow, when he should give us a grand reception.”

“Saturday,

15th. - Having got our presents ready for the king, we were called about

I0 a.m. Great crowds lined the way with drums and a band. The king was

dressed and sitting in the great court, or rather in the adjoining room,

while the chiefs thronged the court. . . . Our presents were produced, the

king and chiefs being delighted, calling Massudi (coastman) to witness how

we gave whole bales of what the Arabs and coastmen sold at the rate of a

couple of yards for a slave or a tusk.” [“When

the half-caste Arabs saw these gifts their resentment knew no bounds. Every

day they agitated at court, and succeeded in turning the chiefs against us.

I had put them to confusion on every occasion before, when they brought

forward their false creed at court, and the king had got so disgusted with

them that he frequently asked me if he should send them away. I told him,

however, not to do so until English traders came. I knew that if no

merchants at all were here, demands would be made on us to supply articles

we could not meet. These fellows have now got the chiefs to believe that we

ought to have given them rich presents also. The king is much influenced by

his chiefs, and allowed much evil talk against us. - A. M. M.”

]

“Tuesday,

I8th. - As we were breakfasting at the oval table (which I had made by

screwing together the two bulkheads of the Daisy, and mounting on six ash

poles stuck in the ground, at which we can all comfortably sit, like King

Arthur and his knights, without any struggle for pre-eminence), and making

arrangements as to the best manner of dividing the work every day, an order

came down for us all to go up .... When we were called in we were told that

two white men had arrived at Ntebe (the port) in a canoe, but who they were

the king knew not.”

These turned

out to be the vanguard of a party of French Romish priests, who, although

the whole continent was open to them, preferred to go where Protestant

missionaries were already at work. It was a time of very great trial to

Mackay and his brethren. Hitherto Mtesa had been most favourable to Mackay

and his teaching, but the interference of these priests bewildered him.

“Every nation of white men has another religion. How can I know what is

right and what is false?” he asked. Mackay appealed to the infallible

Book, and the Roman Catholics to an infallible Church. The battle of the

Reformation was fought again at the court of this heathen king; and, to

complicate matters still further, the Arabs, ever ready to seize an

opportunity of showing their hostility to white men in general, derided the

religion of both. It is possible that Mackay's training and the traditions

of his family prejudiced his mind against these priests, but the following

extracts from his journal are one or two illustrations of their behaviour:-

“Saturday,

Feb. 22nd, 1879. - Went up to the palace, having heard that the men of

whose arrival we had heard were Frenchmen. We suspected that they were the

Romish priests who were reported by Colonel Gordon to be en route for

Uganda. On reaching the outer courts, I found two men who had come with

them, one being a slave of Said bin Salim, and the other the same old

Msukuma who accompanied me to Ukerewe last July. From them I obtained the

information that the strangers were padres, that they had left three of

their number at Kagei, and that all meant to come here to stay. Thus I was

prepared for an audience with the king, which commenced immediately

afterwards. Mtesa of course asked me about them. They had sent him a letter

in Arabic conveying their salaams. I explained to the king what their system

was: that they were followers of Jesus (Isa) as we, accepted the Old and New

Testaments as we, but worshipped the mother of Jesus more than the Lord

Himself, prayed to prophets and saints dead long ago, and taught obedience

to the Pope before their own king. I proposed that Mtesa should send a chief

along with Pearson and myself to see the Frenchmen, and bring back word to

the king explaining who they were, and why come. Mtesa did not accede to

this plan, however, but said he would call the Frenchmen some day, and we

should then understand all.”

“Sunday,

23rd. - We understood that a reception was to be given the French padre

to-day (his com- panion frere

being sick). We went therefore up. Drums were beating, and the general noise

so great that I went to the katikiro, and stated how vexed I was at such

profanation of the Lord's day. I said that he had agreed, and the king also,

to have quietness at least on Sunday; and now, the very first day a European

came, all teaching was forgotten. The judge felt guilty, and said that ‘it

was the king's order to pay honour to their guest.’ I showed the want of

necessity to hold the reception on Sunday, as there was no hurry. The

head-drummer was at once called, and from what we noticed afterwards, I

believe he was ordered to make the reception as quiet as possible. We then

retired to the church, where we spent an hour teaching natives to read and

understand the Creed, when we were informed that the padre had arrived. The

king sat in the side room of the large hall, the throne having been

uncovered, but he did not come out to sit on it. We waited a suitable

opportunity to ask if we were to hold service, but found none. A tall,

stout, awkward white man was then introduced, who made the faintest

recognition of Mtesa, and sat down sideways on a camp stool, with his back

to us. Evidently he was not aware of our presence at all. Soon the king

called me forward, when I rose and shook hands with the stranger, and sat

(or rather kneeled) down by him to interpret. He said he knew no German or

English, but professed his ability to speak in Suahili or in

Arabic. His attempts at being understood,

or in understanding either of these latter two languages, failed, however;

and I explained to the king that Pearson could talk French, and thus we

might be able to converse. But the padre would not reply in his own tongue

to Pearson's questions, answering generally in Suahili (very broken). A

present for the king was produced of seven or eight common coloured cloths

such as go in Unyamwezi, and a French fifteen-shooter (old). I asked where

he had come from, to what Society he belonged, for what purpose he came? Did

our Society know of their coming, and was he aware of there being five

representatives of a Protestant mission here? He replied to most questions

rather unwillingly (at least we thought so). He belonged to the ‘African

Mission Society,’ came from Algiers, had heard of Mtesa’s willingness to

receive white men (he never said Christian missionaries), that their chief

was still at Kagei, that should Mtesa be willing they would all come to

settle here, but if not they would go elsewhere. He was not aware as to

whether or not our Society, or the English Government, knew of their coming,

as he was not chief. He knew there were one or two Protestants here.

“I asked

plainly if he was not come to teach the Romish faith? He said they came to

teach to read and write, and useful arts. I was cross-questioned by the king

about the faith of Roman Catholics, and I stated that they prayed to the

Virgin Mary, to saints, etc., and inculcated obedience to the Pope. I said

we wrote in the same character, and our arts were the same, and in all

respects we were the same as they, only our religions were totally

different. I said that they accepted the Fathers, etc., while we received

only the Old Testament and the New, as we were distinctly disciples of

Isa Messiah (Jesus Christ). On this the gentleman said

politely, in Suahili: “You are a liar.” This he explained by declaring

that I had called him a believer in Islam. I explained calmly that he

had not sufficiently understood, that I had not said so, but that we

believed in Isa. For his mistake and rudeness he was not, however,

polite enough to make any apology. The king asked if in Egypt and Zanzibar

there were not both English and French living together? The padre said that

we and they were not different, as there were people of his religion in

England, and of ours in France. I said, ‘Yes, just as there are Arabs living

in Uganda, but who will say that the Baganda in consequence are Mussulmans?’

This argument was understood.

“Evidently

Mtesa and the chiefs, for selfish interests, would prefer to have as many

English or French or other Europeans here as possible, as thus they know

they will get more presents, and have prestige added to their court.”

“After the

Baraza, broke up the Frenchman asked us if he might not have a few words

with us? We therefore asked him down to dinner at five p.m., and he agreed,

but evidently with no goodwill.

“I talked

earnestly with Kauta and others on the impropriety of having given a state

reception on Sunday, to the exclusion of Divine service. They allowed that

they had done wrong, and after much talk we left.”

“In the

evening our guest showed no signs of coming, so Pearson wrote a polite note

in French, and we sent two boys with it to show him the way. No reply came,

however, and we dined alone. Towards morning, however, one of our boys woke

us up, saying, he and the other had been bound by order of the Frenchman,

who said ‘he did not want our salaams,’ and his servants robbed them of

their clothing!

“Monday,

24th. - Pearson and I went early to the katikiro and asked him to send

for our boy, who was still in custody. I explained also to him that if the

Frenchmen were brought here we should all leave.[“This

was not my own suggestion. All of our party, at the time, were of the same

mind. I thought then, and think still, it was a mistake; but mistakes become

experience, and the best of us call rise to greatness and usefulness and

goodness only in that school. - A. M. M.”]

This, he said, would not be once thought of; still he seemed inclined to

want the Frenchmen here. He said that co one would pay attention to their

teaching. This I declared to be impossible, and distinctly gave him to

understand that we should not remain here, and we should tell the king so.”

“We then went

up to the king's, but did not see him. We talked with the chiefs, however,

as we had done with the katikiro, but they were evidently inclined to have

the Frenchmen come, yet they would not hear of our going away. In the

evening I was sent for. I spoke of the French padres, and distinctly told

the king that we could not remain here if these men were allowed to settle

in the place. Mtesa asked where we would go to? I said the continent was

large, and we could find plenty of room, as the padres could do without

coming here. He said that it would never do to reject Englishmen in favour

of Frenchmen. Besides, he said he could not adopt a new religion with every

new comer. I showed how impossible it was for padres to settle here without

making proselytes, or doing their utmost to do so, even although Mtesa

declared that neither he nor his people would listen to their teaching. I

left him in good humour, the head chiefs being also gratified by a present I

gave each that morning.

“Friday,

28th. - In the afternoon we proposed sending a note to the Frenchmen,

which Pearson wrote in French; and as we wished to make sure of their

receiving it, one of my brethren and I went off with it, taking a fine goat

also as a present. In the letter we said that we had heard they were both

sick, and that our doctor would be glad to see them, and give them medicine,

condiments, or anything else they might wish. We took with us the two boys

whom they had apprehended last Sunday. After passing the hill on which the

palace stands, we met a native sub-chief, who told our boys that if we went

to the Frenchmen we should be bound hand and foot. We went on, however, but

Juma (our Mganda boy) was afraid, and went to stay at the house of the chief

who had thus threatened us. We took him on against his will, and crossed the

swamp, when natives were seen rushing in various directions, some past us,

to a point on the road in front. When we came up to the place, about thirty

men armed with clubs, spears, axes, and guns (their chief being the headman

whom I have mentioned), stood up and menaced us should we go on. My

companion waved some of them aside, and got half through; but I saw the

danger, as he would next moment have been murdered as well as I; so I cried

out to him to desist, and sat down on the bank by the roadside, he

accompanying me. The wild attitude of the gang was truly diabolical. As I

sat down, one fellow with a large native axe jumped up behind me, and I

expected next moment to have my head in two. I looked up calmly in his face,

and his chief had by this time succeeded in driving back the furious mob. I

asked what was the matter, and wanted the chief to sit down and explain.

This he refused to do, as he was too big a man; but I insisted, and at

length he sat down on the ground. He said he had the king's orders not to

allow us to go on. I allowed him to say no more, but said, ‘Let us go at

once to the king.’ Back we went, the mob being by this time increased to

nearly a hundred men, all armed. Half went before and the others remained

with us all the way. When we came to the second court the chief went in and

we were told to sit down outside. This we refused to do, and stood waiting

at the gate for a few minutes. One of the pages came out soon, and asked me

if I had brought medicine for Mtesa, or what I wanted. I sent him in to say

that I wished to see the king at once, but I should not wait more than five

minutes for an answer. As no response was made we left, bringing back the

letter and the goat. All hangers-on in the grounds looked on in silence as

we turned to go, but we were not further troubled.

“Who is at the

root of all this we cannot say. Probably Mtesa had ordered that sub-chief to

look after the padres, and he, on his own responsibility acted as I have

stated. Anyhow, we feel matters have come to a crisis - our lives are no

longer safe, our usefulness is at an end, our teaching rejected, our

medicine refused, Romish priests received contrary to our advice, and no

reply written to Lord Salisbury's friendly letter. [This

letter from Lord Salisbury was anent the massacre of British subjects in

Ukerewe, and the fact that the Nile party were the bearers of it led the

king to think that they must have come for political purposes.

] May God turn good out of evil. We now

intend sending Mtesa a written letter, stating our determination to leave

the country unless he gives us a written promise of protection, food, and

liberty to go about among his subjects. All promises he has now broken, and

we must demand his word in writing in future. I feel confident that all will

turn out well in the end, and that even were we to leave we should soon be

asked back; still at this crisis it is a time of trouble to us, and only the

God whom we serve can bring us out of it.”

Matters came

to such a crisis that the Church Missionary Society party thought they ought

to withdraw from Uganda for a time, and go to Makraka, on the north of the

Albert Lake, which appeared to be an open field. On the 7th of March, 1879,

they heard “it would be well for them to clear out as quickly as possible,

as the king's soldiers were only waiting to kill them all.” On the 30th,

also, an Egyptian soldier (a runaway for years) informed them that “the king

was very ill and had slept in his large hall last night, expecting to die;

also that there was a conclave between chiefs and coastmen, when it was

resolved to murder all the Englishmen should Mtesa die.”

On the 8th of

April, however, their hearts were strengthened by the arrival of Messrs.

Stokes and Copplestone by the Zanzibar route. There were thus seven C.M.S.

missionaries in the country. With the exception of Mr. Pearson, however,

they all soon left. On the 13th of April Mackay writes: “To my mind, the

most likely way to get the king to grant us what we want (food and liberty

to teach) is to live on good terms with him and his chiefs and redeem the

time by using every opportunity of teaching the truth. Persuasion is better

than force, and tact and patience better than urgent demand. I feel sure

that the king will now never grant us what we have begged of him unless we

show him that we are his friends, and are actuated towards him by motives of

real love. Many missionaries in many lands have been worse treated than we,

and have held out for many more years than we have done months, and

ultimately the Lord has rewarded their patience and perseverance. No real

success in missions has ever yet been won without long opposition and

frequent violent persecutions for years. It is therefore unreasonable to

expect that it should be otherwise here. I mean, therefore, to stay by my

post as long as God enables me. If I am peremptorily ordered by the C.M.S.

to return, or if the place becomes too hot for me to stay, I may have to

leave, but I cannot just now think any other course honourable or upright.

“Saturday,

19th April. - Stokes and I went up to court. I asked the king if he was

willing I should bring up my Bible on the morrow and read a little to him

(the public services had been stopped). He at once replied, ‘Yes, bring the

book.’

“Before this

he had asked many questions on the future state. What sort of bodies, what

desires, what clothing? I explained that we should be like the angels, but I

found St. Paul's own excellent simile suit best, the new body given by God

to the seedcorn sowed. Mtesa quite caught this, and explained it to all

present. A little after he asked what we would wear in heaven? I said, we

were not told exactly, for our bodies would require no protection from heat

or cold. I stated plainly that Christ had left us in the dark about many

things in the world beyond, that we might be the more anxious to get there

to know all. He asked me if we had any more knowledge than Jesus taught His

disciples and they further wrote? I said we had not. I feared the padre

sitting behind me would have contradicted this, but he said nothing. Most

probably he did not understand.

“May 15th.

- In the middle of a multitude of questions about the first and second

resurrections, Mtesa abruptly asked me if I knew that the Egyptians had

planted a new station in his territory, and within three days of Ripon

Falls? ‘They are gnawing at my country like rats, and ever pushing their

fortifications nearer.’ I advised him to send two chiefs to Colonel Gordon

to make a friendly treaty with him, settling the question of boundary for

good.”

“‘Gordon is an

Englishman, and so are you: why, therefore, do you take my country from

me?’”

“To this I

merely replied that we had nothing in common: Gordon is practically an

Egyptian, while we are subjects of Mtesa.”

“‘Did you not

promise me arms, and now the Egyptians are upon me?’”

“Mtesa knowing

well that we never made any such promise, and probably not willing to hear a

reply to so foolish a question, dismissed the court at once.”

In the month

of June, however, the king sent an embassy to Queen Victoria in charge of

two missionaries who were returning to England via the Nile. After

their departure the king's friendliness returned, the Sunday services were

resumed, and Mackay's printing press turned to good account in supplying

reading sheets, and portions of Scripture, and pupils increased in number

daily.

Next came

Mackay's unavailing struggle against a sorceress who professed to be

possessed of the Lubare of the Nyanza, and to have power to restore

the king to health.* For a time Mtesa and his chiefs prohibited both

Christianity and Mohammedanism, and returned to their pagan superstitions.

The following

extracts from Mackay's journal at this time will give some idea of his

discouragement after all his attempts to teach the knowledge of the true

God:-

“Monday,

Dec. 29th, 1879. - Again at dawn, or rather before it, the loud beating

of drums and shrill cries of women let us know that the great lubare, Mukasa,

was on her way to pay the king a second visit. I did not know before that

the individual is a woman. Mukasa is not her name, but that of the deity or

spirit which is supposed to possess her. Mukasa is, moreover, not a spirit

of the whole lake, only of some three or four creeks on the coast of Uganda.

I have been told that the formidable foes of the Baganda - the Bavuma, are

continually paying visits to the island where Mukasa lives, and plundering

the god of cattle and slaves

“To-day, I

believe, the audience was of a much more private nature than the previous

one. Some say that not even a single chief, nor a woman, was present at the

interview between the king and the witch. The king has ordered the chiefs to

bring numbers of cattle, slaves, and cowries, and these have been presented

to the lubare in no small quantity.”

“I was

chaffing some natives about their king being obliged to pay tribute (musolo)

to an old woman. ‘It is not tribute,’ they replied, ‘it is bigali,’or

sacrificial offerings to the deity!”

“Wednesday,

Dec. 3Ist. - Early Mufta came, having been sent by the katikiro to call

me. Between 8 and 9 a.m. Pearson went with me. After waiting half an hour at

his door, he came out, dressed up like a tailor's dummy, thinking himself

remarkably smart, but his appearance tended only to excite our risible

faculties. Among other vanities he had tied to his neck a plated railway

whistle which I gave him many months ago.”

“He said that

he expected us early, and that he had an engagement just now, but would soon

be back. We sat down thereupon in the inner court, but loud beating of

drums, as in a procession, excited our curiosity to go out and see. We found

the katikiro standing at his outer gate, while hundreds of people, chiefs

and slaves, were squatting on the ground outside. All, including the judge,

had on a string of green leaves passing over the shoulder like a sash. As we

approached, I overheard the katikiro saying (of Pearson and me) to those

round him, ‘Here come our boys’ (balenzi bafwe), at which they all laughed.”

"When the

procession came up we found it to consist of a whole host of Maandwas,

i.e. wizards and witches - each with a magic wand which they rattled

on the ground in succession before the katikira, he touching the wands with

a finger. Three or four wizards were dressed in leopards' skins, while the

witches were clad in a succession of layers of goatskins - white and black

alternately. The head of the whole - a little witch named Wamala -

was in aprons of goatskins, and had a head cap of many coloured beads. The

consequential air with which they shook their wands on the ground was rather

amusing. Many women carried on their shoulders, entirely wrapped up in bark

cloth, with a garland of the same green leaves as the chiefs, etc., wore,

what were virtually idols, being urn-shaped things called balongo.

These I did not see exposed on this occasion, but others which I saw before

were of the urn-shape, with a large bow handle like a pot. They were

entirely covered with beads sewed in neat patterns over a mass of bark

cloth, having in the heart the umbilical cord of either the present king or

one of his ancestors.

See “A. M.

Mackay, Pioneer Missionary of the Church Missionary Society to Uganda” (Hodder

& Stoughton), p. 145.

“The katikiro

went then to the palace courts with the procession; we thought it useless

waiting, and came home. I am told that the king refused to be seen by the

witches, etc. Wamala, the head one, is stationed near Unyoro, in Mkwenda's

country. She is a rival of the other great witch Mukasa, and once lived on

the lake, but having quarrelled with the other spirit, she went far inland

to rule the dry land, as the other does the water!”

New Year's Day

1880 brought good tidings to Mackay from Colonel Gordon, - viz., that he had

withdrawn all his troops from not only Mruli but also from all the stations

south of the Somerset Nile. Mackay writes: “I am truly thankful to God that

Colonel Gordon has determined on this. Now that Mruli is abandoned, I hope

we shall have much less suspicion lying on us as being implicated in

bringing ‘the Turks’ always nearer. The tone of all Colonel Gordon's letters

is beautiful and spiritual, and I cannot fail to profit much by the

expressed experience of this truly Christian governor.

“When we told

Mtesa that Colonel Gordon advised him to occupy Mruli he was very

pleased, and said ‘his heart was good, and that we were good, and that his

remarks at court before Christmas, that we were spies, were finished now.’

In other words, that he meant to say nothing of the kind again.”

A few jottings

from Mackay's journal in the early months of 1880 will give a glimpse of

missionary life in Central Africa:-

“Jan. 1st,

1880. - Sewed up with silver wire the breast of wounded woman. I do not

think any ribs are broken, but I fear the lung is injured from the cough she

has. Syringed inside of wound in body and re-dressed the hand, cutting away

various broken pieces of bone which I did not discover before.” [This

was a severe ease of gunshot, which happened on December 26th, 1879. “A wife

of Kaitabarwa's was handling a gun which went off (an Enfield with iron

bullet). The bullet passed into the back of the left side, just under the

armpit, out under the nipple, then through the back of the left hand,

shattering the metacarpal bones connecting the forefinger and the wrist. The

bullet passed out under the thumb; we amputated the forefinger, sewed up the

hand, and applied styptics to the wounds in chest. The woman has had a

severe shock to her nervous system and has lost much blood. They brought her

in a hide and we sent her back on a Kitanda.” By March 7th she was almost

well, and able to trip about nimbly.

]

“Feb. 7th.

- Had a day's work at tailoring to-day. Clothes I am almost out of: and have

considerable difficulty in dressing with any degree of respectability. A

coat of checked tweed which one of the Nile party hung up in his hut one

night on the way here was partly eaten up, and partly built into the earthen

wall by morning, by white ants. This coat he handed over to me, and I have

succeeded in putting patches into the back of it so as not to be very

noticeable. I wish I had got some lessons in sewing before leaving England.”

“Sunday,

Feb. 8th. - Continued translation this morning. Read with much

edification a nice little book entitled ‘The King of Love,’ by the author of

‘How to Enter into Rest.’ There are most beautiful thoughts throughout the

book, and much I would seek to live in the realisation of them. ‘God is

never so far off as even to be near.’

“Feb. 9th.

- Patchcd up an old pith helmet inside and out. Cut up and stitched a white

umbrella cover as cover for my helmet. On the whole I have made a decent

head-gear.”

“March 18th,

1380. - It is now announced that another army is under orders to go again to

Busoga to subdue rebels there. Sekibobo is commander-in-chief. A whole host

of chiefs and subs are now going off with him, and of course as many men as

each can muster. All is feudal system here. I wish I knew the real nature of

this war, and if I found it to be a war undertaken to capture cattle and

slaves, I should not fail, God helping me, to show Mtesa and his court the

evil of such terrible work.”

"Sunday,

March 21st. - Kago, one of the most powerful chiefs, and also one of the

strongest upholders of the witchcraft religion of the country, called

to-day.”

“He told me a

series of lies. He said he was not going to war, while I know he is. He said

that the cattle and slaves which they brought so frequently from the East

were only presents from the people! etc., etc. I reproved him for telling

such false-hoods, he being an old man, and a chief, while he should be an

example to the people. Then I spoke solemnly to him about the evil of making

these raids for murder and robbery. I said that, however Uganda might

meantime escape from punishment for such evil work, yet Almighty God saw it

all and would one day call the king and chiefs to account for it.”

On the 2nd

April, 1880, Mackay started for Uyui for a supply of cloth and other barter

goods, as the mission store of such things was all but exhausted, and he and

Mr. Pearson were entirely dependent on the caprice of the king for

subsistence. The Frenchmen kindly lent him cloth to pay his expenses down to

Uyui, and would listen to no promise of repayment. Sorely as they tried to

injure the work of the C.M.S. missionaries, yet in everything else they were

disposed to be friendly. On the above date Mackay writes: “This day two

years ago I started from Mpwapwa for Uyui, and now I am on my way to the

same place once more. May the good Lord, who has preserved me amid no

ordinary troubles and dangers since that day, keep me on this journey and

bring me safely back to Uganda.

“Ten Baziba

carried the luggage to Admiral Gabunga's. The king gave me a present of five

thousand cowries, as he said, to buy food on the way, and not to rob! Paid

four thousand cowries, however, to carry the ten loads to Gabunga's.”

“April 16th.

- Having succeeded in getting a few canoes, we embarked. As the season was

early for marching through Usukuma, harvest not commencing till June, we did

not hurry the canoe-men, allowing them to take their own time. Some of

Gabunga's men who were going to Unyanyembe to sell ivory had joined us, and

altogether we had fourteen canoes in our expedition.”

“May 11th,

reached Kagei safely. Several men of the Romish mission had arrived there,

en route for Mtesa's."

Strange to

say, among the freres was a countryman of his own, a Mr. Charles

Stuart, from Aberdeen! He had been educated at Blairs, on Deeside. Mackay

had several talks with him, but did not expect he would hold out long, as he

lay about all day doing nothing, and imagining himself ill from greasy

French cooking. Mackay says: “I felt sorely tempted to say to him, ‘Och,

man, I could hae forgi'en ye a' yer Popery, but what for hae ye forsaken yer

parritch?' Poor fellow, he had all his clothes stolen from him on the way,

nor had he any book to read. I happened to have a Shakespeare, which I had

taken to while away weary hours in the canoes, and that I gave him.”

The road from

Kagei to Uyui is through a most unsettled and unsafe country, with plenty of

robbers on the way, and continual demands for tribute at every petty

village. Sometimes he had to pay honga three times in a march of seven

miles.

But he was

mercifully preserved from attacks of natives and from highwaymen in the

jungles, although he was only armed with his umbrella. He reached Uyui on

the 5th of June, after a march of twenty days. There he remained five weeks,

and set out again northwards to Kagei. Though it was the month of July, it

was the dead of winter there, and while the sun was sultry through the day,

there were piercing east winds every morning, which he found most trying,

especially as he and his men, in order to avoid the cupidity of as many

greedy chiefs as possible, frequently marched through the night. For

instance, on the 4th of August he says: “By 3 a.m. my men wakened me up,

saying we should start. Got up and looked at the stars (my only clock), and

told them it was yet several hours to daylight, and we might lose our way in

the forest, but if the porters were willing to start, I was ready. Struck

tent, and packed up in dead silence, and by clear starlight set off. Lost

our way at one point, but got on right road again, and the cocks crew as we

stole silently past the hut of the extortionate chief. After more than an

hour we got into the jungle, where we could breathe freely; but walking was

difficult, as in many places there were deep holes like wells caused by the

tread of elephants.”

At the next

village he carne to, he and his party were detained many days before the

matter of the toll was settled. He could get nothing to eat save a few

ground nuts, and a glass of milk was scarcely to be had. But he learned to

be patient of such delays, and embraced the opportunity to instruct the

Baganda lads who were with him, and at the same time he gained much

knowledge from them regarding the superstitions and language of

Uganda. He had made such a rapid journey on the former occasion that much

escaped his observation, but he found now that a common act among many of

the tribes was the kidnapping of boys, such as goat-herds, etc., who were

generally alone, at some distance from the villages, there being always

plenty of Arabs and Wangwana about, ready to buy such children. At such

times the wails of the poor mothers overnight, and. every now and again

breaking out through the day, were most piteous. When will this traffic in

human flesh cease?

At most

villages great crowds of women and children followed him to feast their eyes

on the fair face of the white man. Sometimes, to please them, he got out a

music-box with which they were enraptured; and, strange to say, the popular

tune was “God Save the Queen!”

Then they must

see his arm and his bare foot, while they stroked his hair and compared it

to an antelope's. Until he bared his foot they believed that his boot was

part of himself! But perhaps the greatest curiosity he could show them was

his lamp, for artificial light is quite unknown.

Owing to the

many detentions for honga, he was forty-five days on the way back to Kagei.

While there his three Baganda lads were nearly murdered. They were sleeping

in a hut behind Mackay's house, when some men they had quarrelled with went

and fired a volley into the hut. A terrible scuffle and chase ensued. The

three lads ran for their lives, and the murderous party after them. Mackay

was half-down with fever, but managed with great exertion to persuade the

leader to sit down and talk to him (having previously secreted the objects

of his malice). The Beloochees and Arabs next appeared, armed to the teeth,

expecting to find that Mackay had been attacked, when they were prepared to

aid in murdering him. The chief of the village also arrived, after making

sure that the fray was over. With much trouble Mackay got them all to fire

off their guns and go home.

The Frenchmen

never went to Mackay's aid, although they knew how ill he was, but simply

looked over the fence at the fight!

The journal

continues:-

“I remained at

Kagei two and a half months. I sent on a man to Uganda with a large load of

cowries to Mr. Pearson, as also his English letters, which I had brought

with me. Many days I spent packing all boxes, etc., in raw hide, sewing the

whole with stout twine, to make our goods waterproof on the lake. Much time

I had to spend in bed from repeated and severe attacks of remittent fever.”

“Nov. 2nd.

- Having secured five canoes, I embarked for Uganda with my loads and

servants, leaving the iron boiler parts and machinery well packed in

Kaduma's care. Last of the Frenchmen left for King Roma's in canoes which he

sent for them. (Roma owns all the west side of Smith's Creek, and the road

from thence to Msalala). Pere Levesque alone goes to Uganda, and is

commended to my protection.”

“Nov. 3rd.

- Camp on Juma Island. Pere Levesque and I cross over channel, and spend a

few days at Roma's capital.”

“Nov. 20th.

- At Makongo. Went with Pere Levesque to visit Kaitaba, the king of

Busongora. Gave him a present, and received a fat bullock in return.”

“Dec. 2nd.

- Arrived at Ntcbe, with everything safe. Lake journey has thus occupied

thirty days.”

“Dec. 14th.

- After much delay at Ntebe, and on road, and repeated messages to Mtesa,

got sufficient men under two chiefs to carry all our goods to capital (a

distance of twenty-six miles). Met Mr. Pearson at mission-house, soon after

noon.”

“Dec.16th.

- King held Baraza in great hall and received the Frenchmen in state, as

also the messengers from Roma. The Frenchmen gave presents of gunpowder in

kegs and in tins, guns, caps, bullets military suits, a drum and sundry

small articles.

“Mr. Pearson

and I agreed that we had better not attend the reception along with the

Frenchmen, as we resolved to give no present of anything in the shape of

arms or ammunition, and the contrast between our presents and those of the

Frenchmen might prove unpleasant.”

“The French

party now at Roma's had given that king a large present of cloth, guns, a

revolver, gunpowder, etc., etc. Every one of these things Roma sent on to

Mtesa by some of his own men, these accompanying me. The revolver alone he

kept for himself, asking me most imploringly for my revolver offering me ten

boys for it, promising me also a road to Mirambo's, or anything I liked; and

when all these were declined by me, he tried hard to get me to exchange the

one he got from the padres for mine. But I was inexorable, saying that I

would give such a weapon neither to him, nor to Mtesa, nor to Mirambo.

Roma's object in sending the presents to Mtesa was to ask his aid to fight

against (i.e. spoil and murder) Kigaju, the king of Bukosa, while he

asked me to write a letter from him to Mtesa begging the Uganda fleet. I

flatly refused to do so, saying that we white men came to bring peace

into the country and not war. Strange to say, Roma took me and not the

Frenchmen into his private conference with his head chiefs when he proposed

begging Mtesa's aid. Even afterwards, when I was leaving, and the Frenchmen

all present, he asked me again to recommend him to Mtesa, but did not ask

them. I said before them all that I was a messenger of God, and would

willingly ask Mtesa to make an alliance with Roma, but I would bear no

message asking aid in war.”

“Pere Girault,

who is head of the mission there, felt offended that he was not consulted by

Roma in the matter, especially after he had given the guns and powder, which

were being sent as the price of the army, and walked off in apparent ill

mood.”

“Dec. 18th.

- Mr. Pearson and I went to court. After friendly greetings from the

katikiro and chiefs in the outer court, we went into the inmost court

(except the king's own). After waiting nearly half an hour, the king called

us in. The house was full of naked women, probably nearly a hundred. The

king apologised for making no public reception on my behalf, on the ground

of his illness.”

“Our present

to Mtesa consisted of a few doti of coloured cloth, two fine large knives,

and a score of Rags of diverse colours. We explained that the flags were

international, and none of them English. (They were a set of the ordinary

“commercial code.”)”

“We read the

king a Suahili translation of part of the Committee's letter, informing him

that his men had reached England, had been received by the Queen most

graciously, and had been shown every honour, and that Her Majesty had sent

them to Zanzibar in one of her own men-of-war.”

“Mtesa said

that ‘the fact of his men being so well received in England raised in his

mind the longing to go there himself, but he said the Arabs asserted that he

could not reach there.’ (This is not true, for the Arabs have always, in

court, told him that he would find an open way, and that the English would

be so overjoyed at his condescension, that they would send at once a

hundred large ships to Zanzibar to convey him to London.) I merely said

to him, ‘A great man can overcome many difficulties.’”

Mackay then

showed the king some pictures in the Graphic of Queen Victoria

receiving his envoys. He was delighted, and seemed never to weary looking at

them. The next day Mackay went to court he found his majesty still

entertaining himself with them, and he greeted Mackay with the remark: “I am

determined to go to England, to consult a doctor about my ailments, and I

will leave the queenmother on the throne, in my absence.”

The haughty

chiefs, however, opposed this, saying: “Why should a great monarch like

Mtesa go to England? Queenie (Queen Victoria) sends only small men to

Uganda. Speke, and Grant, and Stanley were only travellers!” |