|

The Malay Archipelago extends for more

than 4,000 miles in length from east to west, and is about 1,300 miles

in breadth from north to south. It would stretch over an expanse equal

to that of all Europe from the

extreme

west far into central Asia. It includes 3 islands

larger than

Britain, and in one of them, Borneo, the whole of the British Isles

might be set down. Sumatra is more than equal in size to Britain.

Java,

Leyte and the Celebes are each larger than Ireland.

At daybreak the islands were in sight.

Flying fish were numerous; more active and elegant than those of

the Atlantic.

They turn on their sides displaying their beautiful fins and taking

flight of about 100 yards, rising and falling in a most graceful

manner. The coast was very picturesque. Light coloured limestone rocks

rose abruptly from the water to a height of several hundred feet, and

were clothed with variant and luxurious vegetation. Little bays and

inlets presented beaches of dazzling whiteness. The water was

transparent as crystal. I was in

a new world

and could dream of the wonderful products hidden in the rocks, forests,

and the azure abysses. But few European feet had ever trodden these

shores or gazed upon its

plants and animals,

and I could not help speculating what my wanderings might bring to

light.

I landed at a trading settlement near

Ternate. It has a clear entrance

from the west

among the coral reefs, and there is a good anchorage. The beach is

backed by a luxuriant growth of lofty forest. The traders here are of

the Malay race. The Moluccas are the spice islands, and the native

country of cloves. Drake and early voyagers purchased the spice cargoes

from the Sultans and Rajahs, and not direct from the cultivators.

Nutmeg and mace were brought here from New Guinea. In the trader’s

house are bundles of smoked tripang or beche de mer, dried shark fins,

mother of pearl

shells and

birds of paradise.

The food we obtain regularly is rice, sago, and fish and cockles of very

good quality. Fresh water is carried in vessels suspended by a rattan

handle. *

Natural History of the Moluccas, in The

Malay Archipelago

Alfred R Wallace, English naturalist 1823 – 1913 (adapted)

In October 1965 when in Moscow with an international group

studying the Soviet system of marine and fisheries education, we heard

that there had been an attempted coup in Indonesia. We paid little

attention to that as the bigger news was the outbreak of war between

India and Pakistan. What had happened in Indonesia was that a group of

communists in the military, with the encouragement of the Foreign

Minister Dr Subandrio, and the active assistance of the Air Force chief,

Omar Dhani, and Chairman Aidit of PKI, the Indonesian Communist Party,

who was a cabinet member, (and some later claimed, with the tacit

agreement of President Sukarno), had rounded up seven leading generals,

taken them to the Halim airforce base, murdered them, and had their

bodies thrown into pits. The abductions and murders actually took place

during the night of 30th September / 1st October. Why

General Soeharto was not included in the number of those killed, is

uncertain. To this day he has given no clear explanation of his

whereabouts that night. He was either not at home, or was regarded as

sympathetic by the plotters. As head of the major commando force in the

country, many Indonesians believe that he must have had some advance

warning of the coup attempt. For some tense days, matters hung in the

balance, then Soeharto moved his KOSTRAD commando troops into action,

and got the rebel units to move out of Jakarta.

Indonesia’s first

President, Sukarno | President Soeharto who deposed Sukarno after the

failed 65 coup

The coup attempt

suffered from the need for secrecy, and poor communications between the

plotters forces afterwards. Sukarno was placed under virtual house

arrest, but without much publicity on that. Soeharto then got the loyal

troop units to act together, and they went through Java killing and

capturing the communist elements. They also seized the opportunity to

settle scores with suspect groups in the country. Published reports

since indicate that the CIA had assisted by giving lists of names of

‘suspected communists’. It is believed that well over 200,000 persons

suspected of being active communists were shot, but many were members of

extreme Muslim groups, and some were simply Chinese traders who were

regarded with jealousy or resentment by indigenous Malays. Many others

(over 100,000), were arrested and were to be incarcerated for a long

time. Ex-foreign minister Dr Subandrio was released only recently, and

died in 2004 at age ninety. Soeharto strengthened his hold on power,

and eventually replaced Sukarno as President. In classic Indonesian

style, the transition was accomplished with smiles and no loss of face.

Sukarno stepped down from his position claiming he was doing so due to

his deteriorating health. Soeharto claimed that Sukarno had authorized

his take-over of the Presidency, but the original signed document has

never been made public.

Reprisals on suspected communists in 1965

The military then

clamped down on all subversive activity. No one could obtain or keep a

job with government who was not cleared of involvement by the security

forces. Many innocent persons were classified as suspect for as little

as belonging to the wrong club in University, or having studied in a

socialist country abroad. My local counterpart in the U.N. project was

one such person. A brilliant officer and extremely diligent worker, he

managed to be cleared to become Director of a government-owned tuna

fishing and export company in the east of the archipelago, but though

the outstanding candidate by far, he never became Director General of

the Fisheries Department. A major question in the security form (which

both foreigners and nationals had to answer), was, “Where were you in

October 1965?” I obfuscated in my replies, since ‘Moscow USSR’

could have given the authorities the wrong impression.

I arrived in Indonesia

in 1973, some 8 years after the attempted coup. The country was still

under strict military control, practically all Ministries and Government

Departments being run by ex-military officers. A few were educated and

competent. Most were dull and ignorant. Many exuded personal greed,

and used their positions of authority solely to line their pockets. To

this day, the Indonesian military receives only a small part of its

budget from the government. It has always been understood that it was

free to develop other sources of funds. The easiest was to control the

vice trade which the army did with some relish. Today, the military’s

businesses and investments are much wider, and include many legitimate

enterprises (like the “Bulog” monopoly on rice distribution,

which has put up prices and hampered national self sufficiency), and

some less than legitimate ones.

We landed at Kemayoran

airport in the middle of Jakarta, which, though large, was a much

smaller city then than the megalopolis it is today with over 12 million

residents. Kemayoran airport was small and welcoming. It appears in an

early Mel Gibson / Sigournay Weaver / Linda Hunt film, “A Year of

Living Dangerously”, that portrays the period of the attempted

coup. It is also drawn with some accuracy in one of the “Tin-Tin”

cartoon books, Flight 714, in which the little reporter has some

adventures in Indonesia and the region. (That cartoon book also quotes

bahasa Indonesia conversations accurately, which impressed me).

Halim air force base

became the next national airport before the present large Sukarno-Hatta

airport was built on the east side of the city.

Poster for the film ‘A Year of Living

Dangerously’

The Fisheries

Department was most fortunate to have one of the most able and visionary

of the Director-Generals in the Government. Admiral Nizam Zachman had

both flair and tenacity. He had decided early on that Indonesia was to

develop its own offshore fleets, and would control its own seafood

exports. I met him in his office in Salemba Raya, where before a large

wall map of the archipelago, he spelled out his vision and plans for the

sector. Prior to that, when passing through Rome where the UN Food and

Agriculture Organisation had its headquarters, I was briefed by Herman

Watzinger, one of Thor Heyedral’s men on the Kon Tiki expedition, who

had gone on to become Director of Fisheries in FAO. The contrast was

interesting. Zachman simply painted a picture of what the country’s

fisheries needed and urged me to get on with the job. Watzinger was

more concerned that I conduct myself circumspectly and diplomatically at

all times, and whatever happened, that I avoid getting “kicked out of

the country”.

We traveled by minibus

past innumerable paddy fields along the north Java road to Tegal, our

destination in the central Javanese province, a journey that took the

best part of a day due to the narrow road and the traffic that included

buses, trucks, cars, pony-and-trap taxis, motor-cycles, bicycles,

ox-carts, becaks or cycle rickshaws, pedestrians, and an

assortment of animals including cows, bullocks, sheep, goats and ducks.

Tegal was a dusty rural town of some 200,000 inhabitants. Local

industry included a large Japanese-owned textile factory, and some

jasmine tea-flavouring plants. Today the town even has its own

university. Tegal lay between Cirebon to the west and Semarang to the

east, about half-way between Jakarta and Surabaya. Local fields were

cultivated for rice and for onions. Over 1,000 sailing canoes operated

from its shallow river in the coastal waters of the Java Sea. Today

there are but 150 canoes and all are mechanized. A motley fleet of

decked boats, trawlers, seiners and gill netters, operated from the main

harbour. Tegal had been a centre of some subversive activity, and

Colonel Untung, one of the plotters, had fled there in an attempt to

escape by boat from Soeharto’s troops. Behind the school and training

centre where our project was based, was the local ‘killing ground’ for

those deemed guilty. Becak operators would not carry passengers there

after dark. Actually Tegal had been a centre of the PKK – Indonesian

Communist party as far back as 1926. In 1945 the Three Regions

Movement, a socialist and revolutionary movement was active there but it

was defeated and destroyed by the Indonesian army. However, at the time

of our arrival we knew nothing of the troubled political past of that

part of Central Java.

Our Project had seven

stations spread out over the 3,000 mile long island state. Tegal was

our main base, but we had a marine and fisheries Academy at Pasar Minggu

in Jakarta, and other training centres in Medan, north Sumatra;

Singaraja, Bali; Manado, north Sulawesi; Ambon; and Sorong, Irian Jaya

(now the Province of Papua). I had to visit all seven sites regularly,

and to help direct and equip the programmes in each location. For that

task I had a remarkably supportive team. My first counterpart was

Patapau Pasau, an amiable local officer, but he was changed later by the

man who was to be my chief counterpart for most of the 5 years.

Soepanto had been educated in Jogjakarta, and had undergone marine

training in Yugoslavia. He was extremely hard working, wholly

determined to succeed at every task, and had a sharp, analytical mind

when addressing problems. He and his wife, a general’s daughter, became

dear friends of ours.

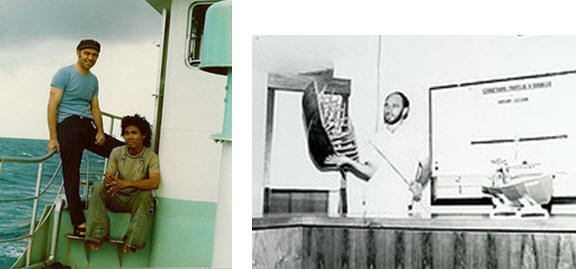

A typical Indonesian prahu canoe

My Project centre in central Java, with a

visiting international group

I also had a team of

fine expatriate officers, hailing from Germany, Denmark, Japan, Korea,

and the Philippines. Later we had specialists join us for shorter

periods, and they hailed from Iceland, Spain, the Netherlands, and the

USA. The station was well equipped with workshops, net sheds, a

navigation bridge, and an ice plant. It had dormitories which

accommodated up to 250 students and trainees, and we had a fleet of 17

training vessels. The German marine engineer ran the several workshops

with shipyard precision, and to German technical standards. Trainees

filed, cut and machined metal till they were able to make almost any

component of a fishing vessel or its machinery. Future graduates of his

courses were to obtain responsible work in the engine rooms of large

ships abroad. The Danish fishery technologist, later to be an ADB

project officer, was equally demanding of the deck students, all of whom

had to learn to splice rope and wire, and to rig and repair every kind

of net used. They still use his shrimp trawl designs in Indonesia

today. Navigation was taught by ex-Indonesian Naval officers who were

competent and reliable.

With Einar Kvaran of Iceland at the

training centre in Ambon

With Japanese colleagues

On the research vessel Lemuru in the Java

Sea Conducting a vessel technology class

Within 12 years of the

project commencement, Tegal and out-centre graduates had replaced all of

the foreign officers (mostly Japanese and Korean) on the joint-venture

fishery vessels operating in the country. The whole project produced

120 fishery high school graduates, and 380 technical course graduates

each year. A number of Diploma students were trained at the Academy in

Jakarta, for work in fish processing plants. Initially most deck and

engine trainees were posted to serve on joint-venture and

government-enterprise vessels fishing for tuna and shrimp. Occasionally,

we had classes of graduate students from the Universities in Bandung and

Bogor, who came to get a taste of practical fisheries work. They were

fine, intelligent young men whose questions in class would range beyond

fisheries to social, environmental and economic issues facing the

nation.

The research side of

the project work focused chiefly on the operation of an FAO research

vessel which was equipped for trawl and purse seine fishing, and had a

range of electronic and navigational equipment. I skippered it one year

for a few months when the Icelandic Captain was on home leave. It was a

memorable experience, sailing west to Sumatra, past Krakatoa island,

(the site of the volcano eruption of 1883) then around Java, Madura and

Bali, and east as far as the island of Timor, then blissfully unaware of

the troubles that lay ahead for its people. The seas we explored

contained a variety of fascinating marine life, - whales, sharks,

dolphins, turtles, tunas, swordfish, colourful reef fish, sardines,

mackerels, shrimp, lobster, squid, sea snakes, and sea cucumber. We

sailed past Kimodo island but did not stop. On our way along the

southern coast of Flores we came upon a volcanic island that had

appeared from a depth of 70 metres, and was still venting sulfuric

steam, and throwing hot rocks into the sea. Two years later I sailed

through the same stretch of sea only to find that the volcanic rock had

vanished without trace.

At a new sea volcano off Flores

The engineer of the r/s

Lemuru, was Jose Alamanar Sansalone, from Spain. In addition to

being a fine engineer and seaman, he had a particular interest in

wildlife, and was never without an animal or reptile of some

description. His activities would be seen as illegal today, but

conservation laws were in their infancy in the sixties and seventies,

and so Jose had been able at different times to keep orang utans,

gibbons, crocodiles, snakes, parrots, toucans, bears, bush babies, and

an assortment of other intriguing pets. Our kids loved him for that.

He was a bachelor then (what wife would have put up with all the

animals!), and though he had many girl friends, showed no signs of

settling down. Later he met and married an ex-nun of all people. Maria

del Carmen, a truly lovely girl, was a teacher of psychiatry who had

entered a convent after graduating. However, she became uncertain of

her calling, and was granted a one-year’s leave of absence from her

order. I think this was prior to the time of John Paul II who would

probably not have granted a dispensation. Her father was FAO country

Representative in Cuba where he met Jose. Carmen and Jose were

introduced, and that was the end of her career in the cloisters! They

became dear friends of ours, and later visited us in Scotland. We were

entertained in their homes in Denia, Spain, and in Santa Cruz,

Tenerife. Now in retirement, Jose has blossomed as an artist. His

paintings and bronze sculptures are regularly displayed at exhibitions

in Spain. Two of his paintings adorn the wall of our living room in

Scotland.

Few in Indonesia spoke

English in those days, particularly in the countryside, so we had to

acquire a minimum skill in bahasa Indonesia. Our children also picked

up bits of the Javanese dialect, but we found bahasa was enough to

contend with. In some ways it is a beautifully easy language, having no

tenses or conjugations. We also grew to enjoy Indonesian food which is

liberally spiced with sambal or crushed chilies. The rice was

especially tasty. Our cook used to purchase the most flavourful

slow-growing local varieties which were so delicious, you could eat it

without any relish. It was like eating freshly baked bread. I have

been suspicious of genetically modified cereals since. The modern

varieties of rice taste like sawdust in comparison.

Crew of the research ship

Gunung Merapi, a volcano we observed

daily from our living room window in central Java

The Indonesian culture,

was well worth the effort to appreciate. The people are so polite, and

so gentle and passive in the way all is said and done. The politeness

can be misleading. A “yes” will usually mean “Yes, I hear and

understand what you are saying”, rather than “Yes, I agree with

you, or will do what you request”. A “Yes, but”, is normally

a pretty clear negative. Many foreigners made things unnecessarily

difficult for themselves by failing to detect the nuances in speech and

body language. The oriental smile can be as misleading as the oriental

“yes”. It is infra-dig in that culture, to show feelings of anger,

embarrassment or disappointment. So they will respond with a smile at

times when that could be misleading to a Westerner.

I read Conrad’s Lord

Jim, when in Indonesia, and was most impressed by the detailed and

still relevant descriptions of ports from Zamboanga Philippines to

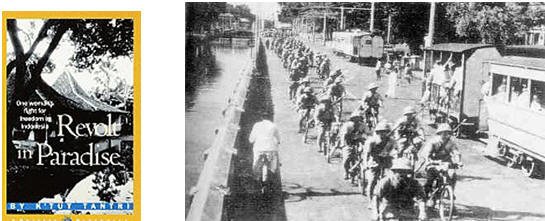

Penang Malaysia. I also read K’tut Tantri’s “Revolt in Paradise”.

This is an account of the immediate post-war struggle for

Independence by a British born American lady who lived in Bali before

the war, was practically adopted into the family of the Raja in Bali,

and who came to be known by the Dutch as “Surabaya Sue” for her

pro-independence broadcasts from that city.

Krakatoa island I used to sail around

in the Sunda Strait. Lord Jim - Conrad’s fascinating book

Back in Java, the Indonesian people rallied behind their

new government, spurred on by Radio Pemberontak in Surabaya, where the

charismatic Ketut Tantri broadcast regularly. The ill-designed

intervention failed, and the British withdrew in December 1946. Dutch

forces continued to fight the national movement, often using Ambonese

soldiers, and thus sowing the seeds of the conflicts in that island to

this day. They left Indonesia in 1949, but held on to Irian Jaya, the

northern part of Papua New Guinea until 1962.

A Remarkable Colonial

Administrator

Few in Britain are aware

that Indonesia, or rather, Java, was a British colony from 1811 to 1816.

This was a short interlude in the long period of Dutch rule of the East

Indies, that was organised as a result of the Napoleonic wars. The

British Lieutenant Governor was a young and relatively unknown colonial

officer who was sponsored for the position by Lord Minto. He was

head-quartered at Bogor in the elevated part of west Java, on the road

to the tea plantations at Puncak Pass, and some 40 miles south of the

seaport capital of Batavia (the modern Jakarta). An example of the best

of the colonial administrators that Britain produced, he set to work

planting botanical gardens and undertook numerous surveys of the

island. Sadly his first wife died of fever and was buried in the

beautiful Bogor garden. In 1816 Java was handed back to the Dutch and

the young administrator was made Lt. Governor of Benkulu in West

Sumatra. (Benkulu lay near the island of Nias which was struck by the

huge tsunami wave of 2004 and the earthquake of 2005). In 1819 he was

posted to a small trading port on an island off the southern end of the

Malaysian peninsula. The administrator applied himself to development

of the island port which soon became the main trading station in the

region. The island was Singapore, and the officer’s name was Stamford

Raffles – later to be knighted for his services and memorialised in the

name of the prestigious Singapore hotel and its partner group of luxury

accommodation. Amazingly, when Raffles retired to England, jealous

British officials denied him a pension. He died in somewhat penurious

circumstances in 1826.

And a not so Prescient

One

The British were back in

Indonesia 130 years after Raffles, when in 1945 – 46 they occupied the

country to root out the last of the Japanese forces, and to ensure the

return of Dutch colonial rule. Unfortunately they landed just as

Indonesia declared its Independence under Bung Sukarno and Mohammed

Hatta in August 1945. Lord Louis Mountbatten had sent General Sir

Philip Christison to command British and Empire troops from Batavia

(Jakarta). (I later came to know one of his officers, Major Fred Ray,

who was at one time posted on the lighthouse island off the entrance to

Batavia port. I think of him every time I fly over that island on

flights approaching Sukarno-Hatta airport). General Sir Philip tried to

suppress the independence movement with inflexible single- mindedness.

700 of his troops were to die over the next year, including the more

reasonable Brigadier Auburn Mallaby who was negotiating for an agreement

with Sukarno’s forces in Surabaya, when General Christison over-ruled

him and dropped leaflets on the city demanding immediate and total

surrender. The Labour Government of Clement Attlee supported the return

of Indonesia to Dutch control, and Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin refused

to permit a United Nations committee of enquiry.

Revolt in Paradise, - K’tut Tantri’s

Troops entering Batavia (Jakarta) 1942

account of the independence struggle

Surabaya Sue

K’tut Tantri, is best known by the Indonesian name given

to her by the Raja Bangli of Bali who practically adopted her into his

family. She was an independent minded, talented, determined , artistic

person whose real origins are somewhat obscure. Possibly due to her

being regarded as a dangerous subversive by the Japanese, and later by

the Dutch, she had a number of pseudonyms, and it is now difficult to

determine which were her real names. She has variously been referred to

as Muriel Pearson, Muriel Stewart Walker, Miss Manx, Miss Daventry, Miss

Oestermaan, Miss Tenchery, etc. Timothy Lindsey, in his recent book,

The Romance of K’tut Tantri and Indonesia, has tried to clarify

her life as far as its details can be ascertained.

She was born in either 1898 or 1908, in Glasgow,

Scotland. Her parents were from the Isle of Man, and her father died

during the first world war. She went to the USA with her mother around

1930, where she worked for British magazines writing about Hollywood and

the cinema. She became a U.S. citizen. After seeing an intriguing

film about the island and culture of Bali, she traveled there in 1932,

with the idea of painting and studying the culture. Shortly after her

arrival in Bali, she met Raja Bangli and became a part of his family.

She died her red hair black at the Raja’s prompting as red hair was not

culturally acceptable. By 1936 it appears she left the Raja’s house and

set up a hotel on Kuta beach that became a meeting place for artists and

visiting celebrities.

K’tut had been married in America but broke early with

her first husband. In Bali, there were rumours of a romance with the

Raja’s son, and later with a gifted male dancer of international renown,

“Mario” Ketut Marya. But no second marriage ever took place.

During the war she became increasingly active in the

independence movement, and for a time was imprisoned and by some

accounts, tortured by the Japanese. The Dutch claim she collaborated

with the Japanese or spread propaganda for them, but this is unlikely

though it was a common Dutch accusation against the supporters of

Soekarno and the nationalists. Her most prominent role was as a radio

broadcaster for the Indonesian movement, from a base in Surabaya. It

was this activity that prompted the Dutch to give her the nickname

‘Surabaya Sue’. To this day, Dutch accounts of her life and work

are somewhat derogatory. But there is no doubt that K’tut displayed

much courage and fortitude, and that she was a considerable help to her

adopted country. Australia accepted Tantri for a period till the Dutch

withdrew after recognizing Soekarno’s national government.

After Indonesia achieved its independence, K’tut Tantri

was less involved in its politics, but worked for the fledgling Ministry

of Information. All who knew her say that despite her remarkable life

and achievements, she was a difficult person, and this may explain why

no permanent position was found for her. She wrote her well known book,

‘Revolt in Paradise’, which was published in 1960, and soon

became an international best-seller.

They say that in her

senior years she showed signs of dementia, and became an embarrassment

to Indonesian embassies in the USA and Australia, by arriving uninvited,

and being reluctant to leave. Nevertheless, she lived into her nineties

and died in Australia in 1998. Her ashes were scattered in Bali at her

request.

If at all possible,

readers should get a copy of Revolt in Paradise from the

library. It is a moving well-written account of Indonesia’s struggle

for independence, and of the life and culture of the island of Bali,

over half a century ago. They will not regret the effort.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Although the largest Moslem country in the world, Indonesia

has been blest with a form of Islam that is largely tolerant and

respectful to the outside world. When attending a Gereja Protestan

Indonesia church (the Indonesian Protestant church that sprang from the

Dutch Reformed Church) in Sumatra, I have been pleasantly surprised to

see veiled Moslem students in attendance. They were required to attend

a Christian church occasionally and observe the worship, to be more

fully informed on other faiths. Such open contact with other faiths

would seldom be seen in other Moslem lands. To be fair, I have

discussed matters of faith, the Bible and the Koran, with Moslems in

Arabia, Africa, central Asia, and the far east. On a personal level, I

have found them to be respectful, willing to listen, and also prepared

to discuss painful issues, and to share their own heart beliefs.

Clearly there are extreme groups in Islamic society in most Moslem

lands, as there are some extremist ‘Christian’ or sectarian groups in

the USA, Northern Ireland, Uganda, and other countries, as well as

extremist Hindu groups in India and militant Buddhist groups in Sri

Lanka. Mercifully, they are all a minority, but nonetheless can wreak

much havoc and bloodshed.

There were 90 million

people in Java when I arrived in the country, and 130 million in the

whole country. Today the population numbers over 200 million. I could

not imagine where all of the thousands of kids running around the

streets were to get food, clothing, education, jobs, and housing. Many

of their fathers were crewing sail-boats or pedaling becaks for a

wage of perhaps Rp 6,000 a month, or less. Their mothers may have been

working in the rice paddies, the textile factories, or the batik dyeing

sheds, for about the same amounts. The basic monthly wage was equivalent

to US $ 15 or just above ₤ 9 then. How could they survive on such low

incomes ? This was something I wrestled with for a long time, and never

ceased to ask those willing to discuss, how the poor people existed.

Map of Indonesia

It was around that time

I read Small is Beautiful for the first time. This is the

prophetic treatise written by the renowned economist Dr Ernst Fritz

Schumacher. He had been a Rhodes scholar, and a participant in the

Bretton Woods conference, then later made economic adviser to the

National Coal Board in Britain, but his heart was in third world

development. He founded the Intermediate Technology Group and was a

leading member of the Soil Society. For me, struggling to come to terms

with the formidable problems of bringing remunerative work and food and

a future, to a vast nation like Indonesia, reading Schumacher was like

putting on spectacles and seeing these problems in focus for the first

time. When in Africa, I had debated with departmental economists over

the direction of the interventions we were making, and whether they were

really in the people’s long term interest, but had no answers to the

arguments of conventional economics. Now, here was an economist of

stature, challenging the very basis of much of modern development

theory, and showing us a better way to a sustainable future on planet

earth.

The sub-title of the

book is Economics as if People Mattered. It painted a lucid, if

alarming, picture, of the phenomenal growth of pollution and industrial

production in the post-war world, of the escalating consumption of

irreplaceable fossil fuels, mainly petroleum, and of modern industry and

technology’s treatment of human beings and their aspirations as if they

just did not matter. It also challenged the sustainability of growth

and market systems based on human greed, and the impact of globalism on

poor societies.

Raising the Indonesian flag to

commemorate independence day

Most of what Schumacher

proclaimed is now accepted as sane and sensible by the United Nations

and the majority of development agencies, if not by the governments of

the USA and the UK, and the major global industrial corporations. But

in the early 1970’s it was considered very new and radical, even though

Schumacher had accurately predicted the OPEC oil crisis 5 years before

it occurred. I began to debate the issues with World Bank economists,

and to write some papers based on the application of Schumacher’s

theories and principles in my own work. I found that most economists

had never really thought out the social and environmental implications

of their policies. To them an efficient business or economic system was

one that used the fewest number of human beings, and made the greatest

profit for the owner, regardless of how much capital it required, or how

much energy it consumed, and with scant attention to the environmental

problems it created.

Some of my ideas were

accepted surprisingly by the Asian Development Bank, and somewhat more

understandably by developing country governments. Dr Shei, the head of

the Agriculture Department of ADB, was remarkably sympathetic. At my

suggestion, and following a meeting with his senior staff, Dr Shei

financed a regional workshop and conference on the application of

alternative and renewable energy systems, which I organized together

with a visionary American research officer, the late Dr Ian Smith of

ICLARM (now WorldFish). But when I wrote a paper for FAO, for the

Indo-Pacific Fishery Council meeting in Japan in 1979, it was banned

from circulation within FAO Rome, and remained so for two years. The

Organisation even refused to agree to my attendance at the Latin America

Fisheries Symposium to which I had been invited by the Government of

Mexico whose officers had read my IPFC paper. However I was able to

take leave of absence for that period. But more of that later.

Small is Beautiful, - E F Schumacher’s

marvellous book which opened my mind to the

need to protect global resources and to follow an economics that valued

people

Though its population

was poor, Indonesia had enormous natural wealth, chiefly petroleum, but

also nickel and copper, timber, and plantation products, rice, spices,

tea and fish – mainly shrimp and tuna. Its growing industry produced

textiles, batiks, shoes and plastic goods. Domestic production of motor

vehicles was achieved following considerable pressure on Japan, but a

fledgling aircraft business did not fare so well. The Industry Minister

Dr Habibie (a friend of Mrs Thatcher’s who had earlier worked in the

German aircraft industry, and was later Vice President and President),

wasted huge amounts of public money on high-tech aviation projects that

failed. But the biggest financial loss to the country came from the

milking of profits from the oil industry, by the regime. Pertamina, the

national oil company, was the goose that laid the golden eggs.

The figures are

mind-boggling. Someone has illustrated a billion dollars thus: If you

were born at the time of Christ, and if you were still alive today, and

if every day of your life (not every week or month), you had spent a

thousand dollars, - you would still not have spent a billion dollars.

But the Pertamina embezzlers had no problem in stealing such amounts,

and no conscience about it afterwards. One middle-level executive,

whose official salary would have been around $9,000 a year, died in 1979

I believe. His first wife had passed away, and his second wife went

immediately to Singapore to claim his bank accounts there, as also, but

separately, did the children of the first wife. The dispute over who was

entitled to the funds went into litigation and became public knowledge.

The frugal officer had accumulated $30 million. Shortly after, a brave

reporter dared to ask President Soeharto, “Mr President, should we

not re-open the Pertamina case”. His reply was, “No, no, - we

have no proof”. Soeharto surprisingly admitted that a newspaper

report that he himself possessed $70 million in Singapore bank accounts,

was true. In his defense, he said, “But the money is not for me. I

am keeping it for the poor children of Indonesia”.

Soeharto stepped down

in May 1988, and in November of that year he handed over to the state,

seven tax free foundations he controlled. Early next year prosecutors

revealed that he had violated the corruption law. He was placed under

arrest in April 2000, and was charged with involvement in a US $500

million scam. Around the same period, Time magazine alleged that the

former President and his family had amassed a fortune of $15 billion,

some $9 billion of it in Austrian banks. Soeharto issued a defamation

suit against the magazine, but it was turned down by both the district

and high courts in Jakarta. However, in February 2001, the Supreme

Court ruled to stop legal proceedings against the former President due

to his deteriorating health. President Megawati mentioned a possible

pardon for him in December of that year. As I have opined elsewhere, in

the world we live in, only small crooks are punished. Really big ones

usually get off. But they all one day will stand before a Higher

Tribunal.

Soeharto’s family followed in his steps, assisted by an army

of sycophant bureaucrats and boot-licking officials. Each of those

amazingly talented kids ended up with ownership or control of dozens of

large companies. Some were granted monopolies, like the one for

internal air freight, by the Government. One son, Tommy, who was given

a monopoly over the clove trade, became an infamous gangster and drug

dealer. The Supreme Court Justice who sentenced him at one of his

trials, Ir. Safiudin, was later murdered. Tommy was charged with

complicity in the shooting and ultimately convicted. Some talk in the

street even blamed him for the death of his mother, Tien Soeharto,

following a struggle in the family home in which a gun was fired. [Hutomo

‘Tommy’ Mandala Putra was jailed for 15 years for paying a hitman to

kill Judge Safiudin, and for other offences. The sentence was

considered too lenient by many, yet was later reduced to ten years on

appeal. Tommy was released after serving a mere third of the 10 year

sentence. The hired gunman and an accomplice were jailed for life and

are not eligible for remission of their sentences.]

Tommy

was incarcerated in the high security island prison Nusakambangan near

Cilacap on Java’s south coast, but remained there for only three years.

His short-lived business empire had been run from a lavish building in

Jakarta city centre, Gudung Timor. After the collapse of the corrupt

enterprises, the building was taken over by the newly created Ministry

of Marine Affairs and Fisheries with which I worked on a number of

Bank-financed projects. So I was a regular visitor to the site of

Tommy’s former kingdom. Tommy

was incarcerated in the high security island prison Nusakambangan near

Cilacap on Java’s south coast, but remained there for only three years.

His short-lived business empire had been run from a lavish building in

Jakarta city centre, Gudung Timor. After the collapse of the corrupt

enterprises, the building was taken over by the newly created Ministry

of Marine Affairs and Fisheries with which I worked on a number of

Bank-financed projects. So I was a regular visitor to the site of

Tommy’s former kingdom.

Right : Tien Soeharto , former

first lady

|

Two interesting

generals

Even within the

military regime of President and former General, Soeharto, which

was infamous for its corruption, mismanagement and nepotism,

there were individuals who displayed competence, integrity, and

a commitment to making Indonesia a just and well-ordered

society, with opportunity and protection for all its citizens.

Two such persons were Ali Sodikin and Hoegeng Iman Santoso.

General Ali

Sodikin from Sumedang, West Java, became a naval officer and

rose to high rank in the Indonesian armed forces. He was

appointed as Governor of Jakarta shortly after Soeharto took

over from Sukarno. Jakarta then (and now) was one of the most

populous cities in the world, and it faced the immense urban

problems of all large cities. Known as Batavia to the Dutch,

Jakarta in 1970 had a population of over 6 million persons.

Today it has double that number of residents. Unemployed poor

from rural areas came to the capital in search of work. Lacking

money or a place to stay, they became squatters, erecting shanty

towns on scraps of land beside the canals and railway lines or

the back streets of the city. Sanitation was poor, and potable

water scarce. (All of the early visitors to Batavia from the

times of Magellan, Drake and Cook, mention that they and their

crews succumbed to fevers and disease in that port). The

squatters had also to compete with the growing number of modern

hotels, office blocks and expensive apartments that demanded and

received top priority for electricity, water and urban

services.

Ali Sodikin set

about modernizing the huge city, and resolving its formidable

social and infrastructural problems. He did this with a zest

and an optimism that won him respect and admiration at home and

abroad, even leading to talk of him being an ideal future

leader. That suggestion was not welcome in the Soeharto

circle. Sodikin had resisted efforts by the ruling elite to

over-ride procedures and grab land and businesses for

themselves. So he was seen as stubborn and uncooperative by the

Soeharto family, and in consequence was dismissed from his

position as Governor. The reward for his sterling service, was

to be put in charge of the country’s football team. The spite

of thwarted greed knows no bounds.

Hoegeng Iman

Santoso hailed from Banyumas in Central Java. He attended the

Police Academy in Jogjakarta, and studied at the Military Police

School in Fort Gordon, Georgia, USA. He rose through the ranks

of police service to become the General in charge of Police in

Jakarta. Santoso took his responsibilities seriously, and

sought to introduce discipline and safety measures such as the

compulsory wearing of crash helmets by motor cyclists. He

refused to turn a blind eye to the excesses and illegal actions

of the Soeharto clique and so fell out of favour. Together with

Ali Sodikin he joined the “Petisi 50” group of concerned

intellectuals that challenged the Soeharto regime on a range of

issues. Tired of vainly fighting corruption, General Hoegeng

eventually resigned and took up a civilian career with TVRI,

leading a family singing group that specialized in Hawaiian

music. Our family greatly enjoyed that splendid weekly

entertainment programme in the 1970’s days of the single-channel

black-and-white television in Indonesia. Hoegang’s wife Mary,

also a quality singer, had a cheerful outgoing personality, but

to me, Hoegang himself always looked sad, as though he carried

the weight of Indonesia’s troubles on his shoulders. |

There is one thing that

must be said in favour of Soeharto and his 32 year rule. Despite all

the corruption and strong-arm tactics, the smiling General gave the

country stability. There was economic growth, and an absence of the

ethnic and religious strife that was stirred up after his resignation.

A young Indonesian government officer, a Moslem, said to me in 1995 when

we were in a Jakarta shopping centre in December, where Christmas music

was being played over the sound system, “Isn’t this a great example

of the tolerance of the Soeharto administration? Would there be as much

celebration of a Christian festival in any other Moslem state?”.

Below : with the Minister of

Agriculture, Indonesia

Meeting with an East Timorese officer.

My own view of the

cause of most of the troubles since then, from East Timor to Banda Aceh,

and to Sulawesi, was that the hoodlums who set the different groups

against each other were financed and organized by former Soeharto

loyalists in the Indonesian military who had lost their privileged

positions. They hoped that if sufficient unrest came about, then

martial law would be declared and they would be back in power. This has

since been confirmed publicly in the national press, and in most other

books on that sad period. General Wiranto himself, Soeharto’s armed

forces chief, has been indicted as a war criminal by a court in East

Timor. That did not prevent him from continuing to seek high office

including the Presidency itself in 2004. Thankfully, however, he was

well beaten at the polls.

The Bali bombing was

different, being the direct work of Al Qaida type extremists. In East

Timor, together with the Indonesian armed forces, the hoodlums killed

hundreds of thousands of civilians. It is true however that during this

period, the United States (which almost alone in the world supported

Indonesia’s claims on East Timor), continued to provide weapons and

training to the Indonesian armed forces. The USA eventually withdrew

support from Soeharto, but that had more to do with his intention to

cancel an order for American military jets, and to purchase similar

aircraft instead from Europe.

As one who loves the

Indonesian people, and who has experienced much kindness at their hands,

I wish that populous land stability, justice, peace and prosperity.

There is in Java, an ancient legend of a King of Peace who will one day

come to right all wrongs and bring harmony and justice to the people. He

is called “Ratu Adil”. The legend or prophesy is so powerful,

that it commands respect to this day. During the latter period of

Soeharto’s rule, a former Professor of Agriculture, Ir. Sawito, claimed

to be Ratu Adil. He attracted a small following, but was quickly put in

prison by the authorities. Whether it is a Herod of 2,000 years ago, or

a modern despot, - no autocratic ruler welcomes the arrival of a

messiah.

Bali bombing and

Sumatra earthquake and tsunami.

. . . . . . . .

I visited Bali several

times, when in command of the UN research vessel, and when on my annual

tour of our out-centres, one of which was situated in Singaraja.

Together with my family, we often stayed at Kuta beach which we loved.

It is located on the Bali Strait, facing west, and just north of the

airport. K’tut Tantri’s famous little hotel was there. There had been

a bad air crash not long after the airport opened in the late 1950’s.

And of course, in 2002 it was the scene of the dreadful Bali bombing

outrage.

Sumatra I knew well

having traveled from one end to the other of that huge and fascinating

island. I spent over a year in Padang West Sumatra, among the Mening

Kabau people, and had visited Lake Toba and its Samosir island in the

province of North Sumatra, home of the Batak people. The island is home

to a dwindling population of tigers, elephants and orang-utan apes. It

is rich in petroleum, particularly in Riau province on the east coast

facing Singapore. Sumatra still has substantial tropical forests, and

plantations of oil palm, rubber and teakwood. Its northernmost

province, Banda Aceh, is an area of strict Islam that has sought

independence from the rest of the archipelago. In consequence, it was

kept under careful surveillance by the Indonesian military.

But no-one could have

foreseen the disaster that was to strike the area suddenly and without

warning on December 26th 2004 when a tsunami wave caused by a

submarine earthquake, hit the coast with such velocity that over 280,000

lives were lost, and scores of villages wiped off the map. The

surviving population will rebuild their villages and restore the

shattered economy, but the social and psychological scars of the

disaster will remain for generations to come.

Three months after the

tsunami disaster, North-West Sumatra was struck by a major earthquake

that mercifully did not result in a tsunami wave, but which caused

serious damage to certain localities. The island of Nias alone

suffering many hundreds of fatalities. The total number who died from

that earthquake in Sumatra is reckoned to amount to over 1,300 persons.

Coming on top of the havoc wreaked by the tidal wave, this was a double

tragedy for the area. |