|

Woodcock's Nest: Early Breeding of; Habits of, in Spring; First Arrival

of; Anecdotes of; Manner of Carrying their Young — Habits of Snipe —

Number of Jack-snipes — Solitary Snipe.

March 9, 1846. — A

woodcock's nest, with three eggs, was brought to me to-day. Two years ago,

a boy brought me a young woodcock nearly full grown, and fledged, in the

second week of April — the exact day I do not remember. Reckoning from

this, I should suppose that the woodcock is about the first bird to hatch

in this country. A few years ago, it was supposed that none remained in

Britain after the end of winter, except a few wounded birds, which were

unable to cross the sea to their usual breeding-places.

However, since the great

increase of fir-plantations, great numbers remain to breed. In the woods

of Altyre and Darnaway (as well as in all the other extensive plantations

in the country) during the whole spring and summer, I see the woodcocks

flying to and fro every evening in considerable numbers. As early as six

or seven o'clock they begin to fly, uttering their curious cry, which

resembles more the croak of a frog than anything else, varied, however, by

a short shrill chirp. Down the shaded course of the river, or through the

avenues and glades of the forest, already dark from the shadow of the

pine-trees, the woodcocks keep up a continual flight, passing and

repassing in all directions, as if in search of each other. As the

twilight comes on, in the open part of the country, they leave the shade

of the woods and fly down to the swamps and pools near the sea-shore and

elsewhere, to feed during the night. When watching in the evening for wild

ducks or geese near the swamps by the shore, I have constantly seen them

pitch close to me, and commence feeding in their peculiar manner. These

birds must probably come from the Altyre woods, the nearest point of which

is at a distance of two or three miles. In the evening the woodcock's

flight is rapid and steady, instead of being uncertain and owl-like, as it

often is in the bright sunshine. I consider their vision to be peculiarly

adapted to the twilight, and even to the darker hours of night — this

being the bird's feeding-time. In very severe and protracted snow-storms

and frosts I have seen them feeding at the springs during the daytime; but

in moderate weather they pass all the light hours in the solitary recesses

of the quietest parts of the woods, although occasionally one will remain

all day in the swamp, or near the springs on the hill-side, where he had

been feeding during the night. When they first arrive, about the month of

November, I have sometimes fallen in with two or three brace far up in the

mountain while grouse-shooting. They then sit very close, and are easily

killed. The first frost, however, sends them all to the shelter of the

woods. No bird seems less adapted for a long flight across the sea than

the woodcock; and it is only by taking advantage of a favourable wind that

they can accomplish their passage. An intelligent master of a ship once

told me, that in his voyages to and from Norway and Sweden, he has

frequently seen them, tired and exhausted, pitch for a moment or two with

outspread wings in the smooth water in the ship's wake; and having rested

themselves for a few moments, continue their weary journey.

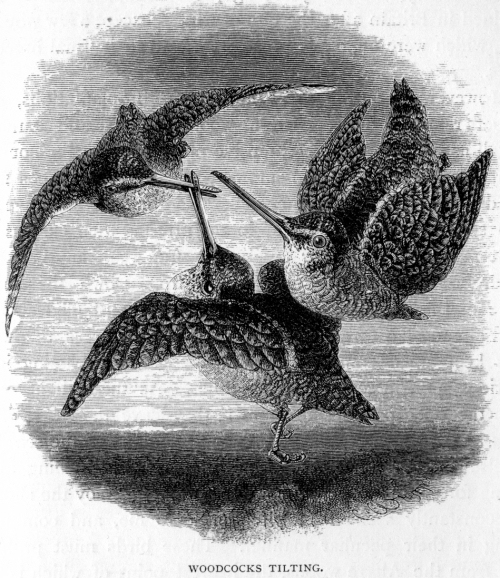

Although those that remain

here breed so early in the year, the woodcocks that migrate do not leave

England till the end of March or beginning of April. In the wild extensive

woods of Sussex, I have often seen them in the evenings, about the

beginning of April, flying to and fro in chase of each other, uttering a

hoarse croaking, and sometimes engaging each other at a kind of

tilting-match with their long bills in the air. I remember an old

poaching-keeper, whose society I used greatly to covet when a boy,

shooting three at a shot, while they were engaged in an aerial tournament

of this kind.

There was a sporting

turnpike-man (a rare instance of such a combination of professions) on

Ashdown forest, in Sussex, who used to kill two or three woodcocks every

evening for a week or two in March and April — shooting the birds while he

smoked his pipe, and drank his smuggled brandy and water at his

turnpike-gate, which was situated in a glade in the forest, where the

birds were in the habit of flying during the twilight.

I rather astonished an

English friend of mine, who was staying with me in Inverness-shire during

the month of June, by asking him to come out woodcock-shooting one

evening. And his surprise was not diminished by my preparations for our

battue, which consisted of ordering out chairs and cigars into the garden

at the back of the house, which happened to be just in the line of the

birds' flight from the woods to the swamps. After he had killed three or

four from his chair, we stopped murdering the poor birds, who were quite

unfit to eat, having probably young ones or eggs, to provide for at home,

in the quiet recesses of the woods, along the banks of Lochness, which

covers afford as good woodcock-shooting as any in Scotland.

The female makes her nest,

or rather, lays her eggs — for nest she has none — in a tuft of heather,

or at the foot of a small tree. The eggs are four in number, and resemble

those of a plover. They are always placed regularly in the nest, the small

ends of the eggs meeting in the centre. When disturbed from her nest, she

flutters away like a partridge, pretending to be lame, in order to take

the attention of the intruder away from her young or eggs. It is a

singular, but well-ascertained fact, that woodcocks carry their young ones

down to the springs and soft ground where they feed. Before I knew this, I

was greatly puzzled as to how the newly-hatched young of this bird could

go from the nest, which is often built in the rankest heather, far from

any place where they could possibly feed, down to the marshes. I have,

however, ascertained that the old bird lifts her young in her feet, and

carries them one by one to their feeding-ground. Considering the apparent

improbability of this curious act of the woodcock, and the unfitness of

their feet and claws for carrying or holding any substance whatever, I

should be unwilling to relate it on my own unsupported evidence; but it

has been lately corroborated by the observations of several intelligent

foresters and others, who are in the habit of passing through the woods

during March and April.

The woodcock breeds a

second time in July and August. I am of opinion that all those which are

bred in this country emigrate about the beginning of September, probably

about the full moon in that month. At any rate they entirely disappear

from woods where any day in June or July I could find several brace. In

September and the beginning of October I could never find a' single bird,

though I have repeatedly tried to do so. A few come in October; but the

greatest number which visit this country arrive at the November full moon,

these birds invariably taking advantage of the lightest nights for their

journey. In many parts of the country near the coast, the day, and almost

the hour, of their arrival can be accurately calculated on, as also the

particular thickets and coverts where the first birds alight.

The snipe also begins to

breed in March, though it is not quite so early a bird as the woodcock.

Snipes hatch their young in this country, breeding and rearing them in the

swamps, or near the springs on the mountains. During the pairing time the

snipes fly about all day, hovering and wheeling in the air above the

rushes where the female bird lies concealed, and uttering their peculiar

cry, which resembles exactly the bleating of a goat, and from which they

have one of their Gaelic names, which signifies the air-goat.

About the end of July and

first week in August the snipes descend from the higher grounds, and

collect in great numbers about certain favourite places. They remain in

these spots for a week or ten days, and then disperse. The rest of the

season we have but few in this part of the country. Particular ditches and

streams near my house always afford me two or three snipes; and as fast as

I kill these, others appear.

Occasionally flights of

jack-snipes come here; generally about the end or middle of October; and

last year I find, on referring to my game-book, that on the 19th of

October I killed eight brace of jack-snipes in an hour or two, finding

them all in a small rushy pool and in the adjoining ditch. Usually,

however, I only find three or four during a day's shooting; but in this

manner I kill a great many in the course of the season, as there appears

to be a constant succession of these birds from October to March, when

they leave us. The jack-snipe never remains to breed here. I can scarcely

call the solitary snipe a bird of this country, never having seen but one

in Scotland, and that was in Sutherlandshire. |