|

Wild Geese: Arrival of; Different kinds of; Anecdotes of Shooting Wild

Geese — Feeding-places —Wariness — Habits — Breeding-places —

Blackheaded Gull — Birds that breed on the River-banks.

On the 2d of March a flock

of twelve wild geese passed over my house, flying eastwards towards the

Loch of Spynie : these are the first birds of the kind I have seen this

spring. On the 6th I hear of the same flock being seen feeding on a

clover-field to the eastward, in the flat country between this place and

Loch Spynie. This flock of geese are said to have been occasionally seen

during the whole winter about the peat-mosses beyond Brodie, there having

been no severe frost or snow to drive them southward.

The first wild geese that

we see here are not the common grey goose, but the white-fronted or

laughing goose, Anas albi-frons, called by Buffon I'Oye rieuse.

This bird has a peculiarly harsh and wild cry, whence its name. It differs

in another respect also from the common grey goose, in preferring clover

and green wheat to corn for its food. Indeed, this bird appears to me to

be wholly graminiferous. Unlike the grey goose too, it roosts, when

undisturbed, in any grass-field where it may have been feeding in the

afternoon, instead of taking to the bay every night for its sleeping

quarters. The laughing goose also never appears here in large flocks, but

in small companies of from eight or nine to twenty birds.

Though very watchful at all

times, they are more easily approached than the grey goose, and often feed

on ground that admits of stalking them. I see them occasionally feeding in

small swamps and patches of grass surrounded by high banks, furze, or

trees. The grey goose appears to select the most open and extensive fields

in the country to feed in, always avoiding any bank or hedge that may

conceal a foe.

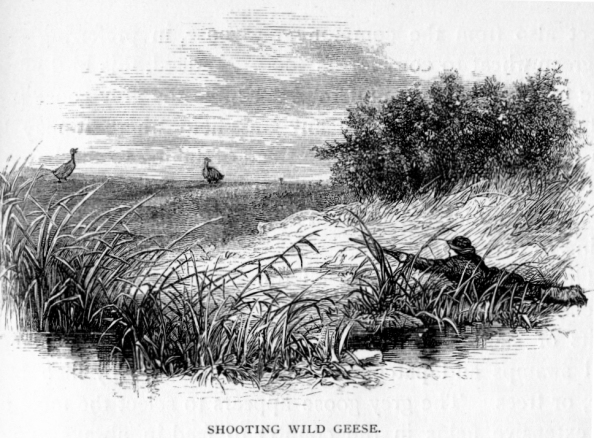

On the 10th of March last

year, when out rabbit-shooting in a small furze cover, I saw a flock of

some fifteen or sixteen white-fronted geese hovering over a small

clover-field not far from where I was. My attendant, who has a most

violent liking for a " wild-goose-chase," immediately caught up the dogs,

and made me sit down to watch the birds, who presently pitched, as we

expected, on the clover-field. I was for immediately commencing the

campaign against them, but this he would not admit of, and pointing out a

part of the field sheltered by a bank overgrown with furze, where the

clover was greener than elsewhere, he told me that in ten minutes the

birds would be there. Knowing his experience and cunning in these matters,

I put myself entirely under his orders, and waited patiently. The geese,

after sitting quietly for a few minutes, and surveying the country around,

began to plume their feathers, and this done, commenced feeding in a

straight line for the green spot of grass, keeping, however, a constant

watch in all directions. "They will be in that hollow in a minute, Sir,"

said Simon; "and then, Sir, you must just run for it till you get behind

the bank, and then you can easily crawl to within thirty yards of where

they will pass." Accordingly, the moment they disappeared in the hollow, I

started literally ventre a terre. One of the wary birds, however,

evidently not liking that the whole flock should be in the hollow at once,

ran back and took up her station on the rising ground which they had just

passed over, where she stood with her neck erect and looking in all

directions. I was in full view of her, and at the moment was crossing a

wet rushy spot of ground; nothing was left for it but to lie flat on the

ground, notwithstanding the humid nature of my locale ; the bird appeared

rather puzzled by my appearance, and my grey clothes not making much show

in the rushy ground and withered herbage which I was lying in, she

contented herself with giving some private signal to the rest, which

brought them all at a quick run up to her side, where they stood looking

about them, undecided whether to fly or not. I was about two hundred yards

from the birds; we remained in this manner for, I dare say, five minutes,

the birds appearing on the point of taking wing during the whole time :

suddenly I heard a shout beyond the birds, and they instantly rose in

confusion and flew directly towards me. As soon as they were over my head

I stood up; the effect of my sudden appearance was to make them break

their line and fly straight away from me in all directions, thus giving me

what I wanted, shots at them when flying away from me, in which case they

are easy to kill. My cartridges told with good effect, and I killed a

brace, one dropping perfectly dead and the other extending her wings and

gradually sinking, till she fell on the top of a furze-bush three or four

hundred yards off, where I found her lying quite dead. It appeared that

Simon, seeing that the birds had observed me, ran round them, and then

setting up a shout, had luckily driven them nolens volens over my head.

They were the white-fronted goose, with pure white spots on their

foreheads. About three weeks after this time, at the end March, large

flights of grey geese appear here, feeding on the fresh-sown oats, barley,

and peas during the day, and passing the night on the sands of the bay,

whither they always repair soon after sunset.

I had passed a great part of several days in endeavouring to get at these

wary birds, and had occasionally killed a stray one or two, but some ill

luck or error on my part (Simon would never admit that his own tactics

were wrong) had always prevented my getting a good shot at the flocks. As

for Simon, he protested that " his heart was quite broken with the

beasts." One morning, however, I got up at daylight and went to the shore

; a heavy mist was rolling over the bay, and I could see nothing, but

heard the wild and continued cry of hundreds of geese answering each

other, and apparently consulting as to what direction they should seek

their morning's repast in. Presently I knew from their altered cry that

the birds were on wing, and were coming directly towards where I was : I

sat down, and very soon a long line of geese came cackling and chattering

within fifteen yards of me, and I killed a brace with no trouble. In the

afternoon, while walking on the shore, I saw a large flock of geese rise

off the sea and fly inland, in a long undulating line, evidently looking

for a place to feed on. I watched them with my glass, and saw the field in

which they alighted, at the distance of at least two miles from me. I sent

for Simon, and started in pursuit. We came within two fields of the birds,

and could advance no nearer without risk of putting them up. On two sides

of the field " in which they were feeding," was a deep open drain ; and

once in this we were nearly sure of a shot. Luckily a farmer was ploughing

in an adjoining field, and though at every turn he approached the ditch of

the oatfield where the geese were, the birds, according to their usual

custom, took no notice of him. We joined the ploughman, and keeping behind

the horses, slipped unperceived by the geese into the ditch, which, by the

by, had in it about a foot of the coldest water that I ever felt. It was

deep enough, however, to conceal us entirely, and following Simon, I went

about three hundred yards down the drain, till we came to another which

ran at right angles to the first; we turned along this ditch, which, not

being cut so deep as the other, obliged us to stoop in a manner that made

my back ache most unmercifully. Simon appeared to understand exactly what

he was at, and to have a perfect knowledge of the geography of all the

drains in the country. Putting on a nondescript kind of cap, made of dirty

canvas, exactly the colour of a ploughed field, he peered cautiously

through a bunch of rushes which grew on the edge of the ditch ; then

looking at me with a most satisfied grin, floundered on again till he came

to another ditch that crossed us at right angles. Up this he went, and of

course I had nothing to do but to follow, though as I occasionally sank

above my knees into cold spring water, I began to wish all the wild geese

were consigned to his black majesty : we went about a hundred yards up

this last drain, till we came to a part where a few rushes grew on the

banks ; looking through these we saw about fifty geese coming straight

towards us, feeding; we got our guns cautiously on the top of the bank and

waited till the birds were within twenty-five yards of us, they then began

to turn to cross the field back again. Some were within shot, however, and

on our giving a low whistle they ran together, preparatory to rising; this

was our moment: only one of my barrels went off, the other having got wet

through, copper cap and everything, during our progress in the ditch. We,

however, bagged three birds, and another flew wounded away, and at last

fell close to the sea-shore, where we afterwards found her. Having

collected our game, I was not sorry to walk off home in double-quick time

to put a little caloric into my limbs, as I felt perfectly benumbed after

wading for such a distance in a cold March wind.

On our way home we saw an

immense flock of geese alight to feed on a small field of newly-sown peas.

Simon was delighted, and promised me a good shot in the morning, if I left

him at the nearest farm-house to take his own steps towards ensuring me

the chance.

Accordingly the next

morning, at daylight, I went with him to the spot: the geese were still

resting on the sands, not having yet made their morning meal. In the very

centre of the pea-field Simon had constructed what he called an "ambush;"

this was a kind of hut or rather hole in the ground, just large enough to

contain one person, whose chin would be on a level with the field. The

ground was rather rough, and he had so disposed the clods of earth that I

was quite invisible till the geese came within a yard or two of me. Into

this hole he made me worm myself while he went to a hedge at some

distance, for the chance of the birds coming over his head after I had

fired. The sun was not yet up when I heard the cackle of the geese, and

soon afterwards the whole flock came soaring over my head; round and round

they flew, getting lower every circle. I could several times have fired at

single birds as they flew close by me, and so well concealed was I with

clods of earth, dried grass, etc., that they never suspected my presence

in the midst of their breakfast-table. Presently they all alighted at the

farthest end of the field from me, and commenced shovelling up the peas in

the most wholesale manner. Though the field was small, they managed to

feed from one end to the other without coming within sixty yards of me;

having got to the end of the field, they turned round, and this time I saw

that they would pass within shot. Suddenly they all halted, and I saw that

something had alarmed them; I looked cautiously out, and saw, in the

direction in which their heads were turned, a large fox sitting upright

and looking wistfully at the geese, but seeming quite aware that he had no

chance of getting at them. The morning sun, however, which was just

rising, and which, shining on his coat, made it appear perfectly red,

warned him that it was time to be off to the woods, and he trotted quietly

away, passing my ambuscade within forty yards, but always keeping his head

turned towards the geese, as if unwilling to give up all hope of getting

one of them. The distant bark of a dog, however, again warned him, and he

quickened his pace and was soon out of sight. The geese seemed quite

relieved at his departure, and recommenced feeding. I cocked my gun and

arranged my ambuscade, so as to be ready for them when they came opposite

to me; presently one or two stragglers passed within ten yards; I pulled

the dead grass in front of my face, so that they could not see me, and

waited for the main flock, who soon came by, feeding hurriedly as they

passed ; when they were opposite to me, I threw down part of the clods and

grass that concealed me, and fired both barrels at the thickest part of

the flock: three fell dead, and two others dropped before the flock had

flown many hundred yards. Simon ran from his hiding-place to secure them;

one was dead, the other rose again, but was stopped by a charge from his

gun. Our five geese were no light load to carry home, as they had been

feeding on the corn for a fortnight or three weeks, and had become very

fat and heavy.

The common grey goose,

after having fed for some time in the fresh-sown corn-fields, is by no

means a bad bird for the larder. But before they can procure grain to feed

on, their flesh is neither so firm nor so well-flavoured. In this country

there are three kinds of geese, all called by the common name of "wild

geese," namely, the white-fronted goose, already mentioned ; the common

grey-leg goose, Anas Anser; and the bean-goose. The latter kind differs

from the grey goose in having a small black mark at the end of their bill,

about the size and colour of a horse bean. This bird, too, differs in

being rather smaller and more dark in its general colour than the grey

goose. It is a great libel to accuse a goose of being a silly bird. Even a

tame goose shows much instinct and attachment; and were its habits more

closely observed, the tame goose would be found to be by no means wanting

in general cleverness. Its watchfulness at night-time is, and always has

been, proverbial; and it certainly is endowed with a strong organ of

self-preservation. You may drive over dog, cat, hen, or pig; but I defy

you to drive over a tame goose. As for wild geese, I know of no animal,

biped or quadruped, that is so difficult to deceive or approach. Their

senses of hearing, seeing, and smelling are all extremely acute;

independently of which they appear to act in so organised and cautious a

manner when feeding or roosting, as to defy all danger. Many a time has my

utmost caution been of no avail in attempting to approach these birds;

either a careless step on a piece of gravel, or an eddy of wind, however

light, or letting them perceive the smallest portion of my person, has

rendered useless whole hours of manoeuvring. When a flock of geese has

fixed on a field of new-sown grain to feed on, before alighting they make

numerous circling flights round and round it, and the least suspicious

object prevents their pitching. Supposing that all is right, and they do

alight, the whole flock for the space of a minute or two remains

motionless, with erect head and neck reconnoitring the country round. They

then, at a given signal from one of the largest birds, disperse into open

order, and commence feeding in a tolerably regular line. They now appear

to have made up their minds that all is safe, and are contented with

leaving one sentry, who either stands on some elevated part of the field,

or walks slowly with the rest—never, however, venturing to pick up a

single grain of corn, his whole energies being employed in watching. The

flock feeds across the field; not waddling, like tame geese, but walking

quickly, with a firm, active, light-infantry step. They seldom venture

near any ditch or hedge that might conceal a foe. When the sentry thinks

that he has performed a fair share of duty, he gives the nearest bird to

him a sharp peck. I have seen him sometimes pull out a handful of feathers

if the first hint is not immediately attended to, at the same time

uttering a querulous kind of cry. This bird then takes up the watch, with

neck perfectly upright, and in due time makes some other bird relieve

guard. On the least appearance of an enemy, the sentinal gives an alarm,

and the whole flock invariably run up to him, and for a moment or two

stand still in a crowd, and then take flight; at first in a confused mass,

but this is soon changed into a beautiful wedge-like rank which they keep

till about to alight again. Towards evening I observe the geese coming

from the interior, in numerous small flocks, to the bay ; in calm weather,

flying at a great height; and their peculiar cry is heard some time before

the birds are in sight. As soon as they are above the sands, where every

object is plainly visible, and no enemy can well be concealed, flock after

flock wheel rapidly downwards, and alight at the edge of the water, where

they immediately begin splashing and washing themselves, keeping up an

almost incessant clamour. In the morning they again take to the fields.

Those flocks that feed at a distance start before sunrise; but those that

feed nearer to the bay do not leave their roosting-place so soon. During

stormy and misty weather, the geese frequently fly quite low over the

heads of the work-people in the fields, but even then have a kind of

instinctive dread of any person in the garb of a sportsman. I have also

frequently got shots at wild geese by finding out the pools where they

drink during the daytime. They generally alight at the distance of two or

three hundred yards from the pool; and after watching motionless for a few

minutes, all start off in a hurry to get their drink. This done, they

return to the open field or the sea-shore.

In some parts of

Sutherland—for instance on Loch Shin, and other lonely and unfrequented

pieces of water—the wild goose breeds on the small islands that dot these

waters. If their eggs are taken and hatched under tame geese, the young

are easily domesticated; but, unless pinioned or confined, they always

take to flight with the first flock of wild geese that passes over the

place during the migrating-season. Even when unable to fly, they evince a

great desire to take wing at this season, and are very restless for a few

weeks in spring and autumn. In a lonely and little-frequented spot on the

banks of Loch Shin, where the remains of walls and short green herbage

point out the site of some former shealing or residence of cattle-herds,

long since gone to ruin, I have frequently found the wild goose with her

brood feeding on the fine grass that grows on what was once the dwelling

of man. The young birds do not fly till after they are full grown; but are

very active in the water, swimming and diving with great quickness.

March is a month full of

interest to the observer of the habits of birds, particularly of those

that are migratory. During the last week of February and the first week in

March thousands of pewits appear here: first a few stragglers arrive, but

in the course of some days the shores of the bay are literally alive with

them.

The black-headed gulls also

arrive in great numbers. This bird loses the black feathers on the head

during the winter, and at this season begins to resume them. I see the

birds with their heads of every degree of black and white just now; in a

fortnight their black cowl is complete. In the evenings and at nighttime

thousands of these birds collect on the bay, and every one of them appears

to be chattering at once, so that the whole flock together make a noise

that drowns every other sound or cry for a considerable distance round

them.

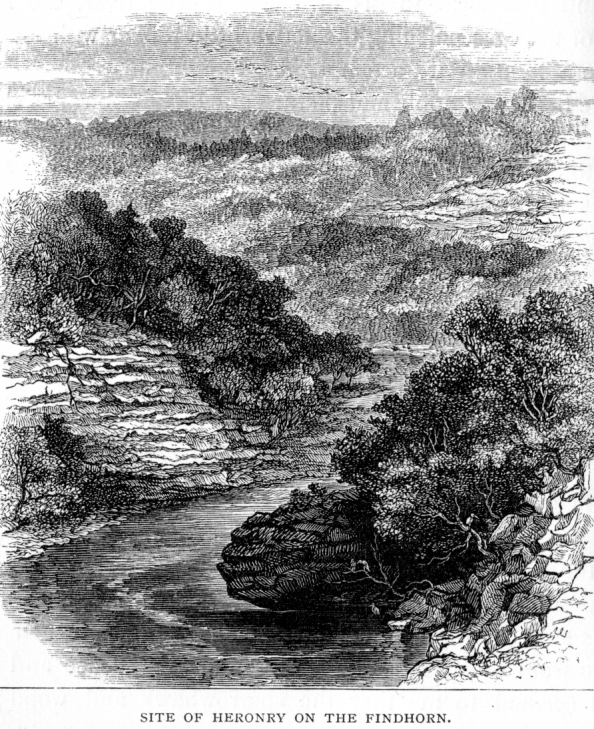

March 6th.—I observe that

the herons in the heronry on the Findhorn are now busily employed in

sitting on their eggs, the heron being one of the first birds to commence

breeding in this country. A more curious and interesting sight than the

Find-horn heronry I do not know : from the top of the high rocks on the

east side of the river you look down into every nest, the herons breeding

on the opposite side of the river, which is here very narrow. The cliffs

and rocks are studded with splendid pines and larch, and fringed with all

the more lowly but not less beautiful underwood which abounds in this

country. Conspicuous amongst these are the bird-cherry and mountain-ash,

the holly and the wild rose ; while the golden blossoms of furze and broom

enliven every crevice and corner in the rock. Opposite to you is a wood of

larch and oak, on the latter of which trees are crowded a vast number of

the nests of the heron. The foliage and small branches of the oaks that

they breed on seem entirely destroyed, leaving nothing but the naked arms

and branches of the trees on which the nests are placed. The same nests,

slightly repaired, are used year after year. Looking down at them from the

high banks of the Altyre side of the river, you can see directly into

their nests, and can become acquainted with the whole of their domestic

economy. You can plainly see the green eggs, and also the young herons,

who fearlessly, and conscious of the security they are left in, are

constantly passing backwards and forwards, and alighting on the topmost

branches of the larch or oak trees, whilst the still younger birds sit

bolt upright in the nest, snapping their beaks together with a curious

sound. Occasionally a grave-looking heron is seen balancing himself by

some incomprehensible feat of gymnastics on the very topmost twig of a

larch tree, where he swings about in an unsteady manner, quite unbecoming

so sage-looking a bird. Occasionally a thievish jackdaw dashes out from

the cliffs opposite the heronry and flies straight into some unguarded

nest, seizes one of the large green eggs, and flies back to his own side

of the river, the rightful owner of the eggs pursuing the active little

robber with loud cries and the most awkward attempts at catching him.

The heron is a noble and

picturesque looking bird, as she sails quietly through the air with

outstretched wings and slow flight; but nothing is more ridiculous and

undignified than her appearance as she vainly chases the jackdaw or hooded

crow who is carrying off her egg, and darting rapidly round the angles and

corners of the rocks. Now and then every heron raises its head and looks

on the alert as the peregrine falcon, with rapid and direct flight, passes

their crowded dominion; but intent on his own nest, built on the rock some

little way farther on, the hawk takes no notice of his long-legged

neighbours, who soon settle down again into their attitudes of rest. The

kestrel-hawk frequents the same part of the river, and lives in amity with

the wood-pigeons that breed in every cluster of ivy which clings to the

rocks. Even that bold and fearless enemy of all the pigeon race, the

sparrowhawk, frequently has her nest within a few yards of the

wood-pigeon, and you see these birds (at all other seasons such deadly

enemies) passing each other in their way to and fro from their respective

nests in perfect peace and amity. It has seemed to me that the sparrowhawk

and wood-pigeon during the breeding-season frequently enter into a mutual

compact against the crows and jackdaws, who are constantly on the look-out

for the eggs of all other birds. The hawk appears to depend on the

vigilance of the wood-pigeon to warn him of the approach of these

marauders; and then the brave little warrior sallies out, and is not

satisfied till he has driven the crow to a safe distance from the nests of

himself and his more peaceable ally. At least in no other way can I

account for these two birds so very frequently breeding not only, in the

same range of rock, but within two or three yards of each other.

|