|

Weasels — Ferrets: Fierceness of — Anecdotes — Food of Weasels — Manner

of Hunting for Prey —The Stoat: Change of Colour — Odour of — Food of —

Their catching Fish: Polecat — The Marten Cat — Habits — Trapping —

Eating Fruit — Activity of: Different Species.

THE bloodthirstiness and

ferocity of all the weasel tribe is perfectly wonderful. The proverb "L'appétit

vient en mangeant" is well applied to these little animals. The more blood

they spill, the more they long for, and are not content till every animal

that they can get at is slain. A she ferret, with a litter of young ones,

contrived to get loose a few nights back, and instinctively made her way

to the henhouse, accompanied by her six kittens, who were not nearly

half-grown, indeed their eyes were not quite open. Seven hens and a number

of tame rabbits were killed before they were discovered; and every animal

that they killed, notwithstanding its weight and size, was dragged to the

hutch in which the ferrets were kept, and as they could not get their

victims through the hole by which they had escaped themselves, a perfect

heap of dead bodies was collected round their hutch. When I looked out of

my window in the morning, I had the satisfaction of seeing four of the

young ferrets, covered with blood, dragging a hen (who I had flattered

myself was about to hatch a brood of young pheasants) across the yard

which was between the henhouse and where these ferrets were kept; the

remainder of them were assisting the old one in slaughtering some white

rabbits. Their eagerness to escape again, and renew their bloody attacks,

showed the excited state the little wretches were in, from this their

first essay in killing.

In the same way the wild

animals of the tribe must be wofully destructive when opportunity is

afforded them. Sitting opposite a rabbit-hole, I one day saw a tiny weasel

bring out four young rabbits one after the other, and carry, or rather

drag them away one by one towards her own abode in a cairn of loose

stones; and, a few days ago, I saw one bring three young landrails in as

many minutes out of a field of high wheat. In fact, as long as she can

find an animal to kill, so long will a weasel hunt, whether in want of

food or not. I have frequently seen a weasel, small as he is, kill a

full-grown rabbit. The latter is sometimes so frightened at the

persevering ferocity of his little enemy, that it lies down and cries out

before the weasel has come up. Occasionally these animals join in a

company of six or eight, and hunt down rabbit or hare, giving tongue and

tracking their unfortunate victim like a pack of beagles.

There is no doubt that in

some degree they repay the damage done to game, by the number of rats and

mice which they destroy (the latter being their favourite food). The

weasel will take up its abode in a stack-yard, living on the mice and

small birds that it catches for some time, and the farmer looks on it as a

useful ally; till, some night, the mice begin to grow scarce, and then the

chickens suffer. Eggs, fresh and rotten, are favourite dainties with the

weasel.

I once witnessed a very

curious feat of this active little animal. I saw a weasel hunting and

prying about a stubble field in which were several corn-buntings flying

about, and every now and then alighting to sing on the straggling thistle

that rose above the stubble. Presently the little fellow disappeared at

the foot of a thistle, and I imagined he had gone into a hole. I waited,

however, to see what would happen, as, from the way he had been hunting

about, he evidently had some mischief in his head. Soon a corn-bunting

alighted on the very thistle near which the weasel had disappeared, and

which was the highest in the field. The next moment I saw something spring

up as quick as lightning, and disappear again along with the bird. I then

thought it time to interfere, and found that the weasel had caught and

killed the bunting, having, evidently guided by his instinct or

observation, waited concealed at the foot of the plant where he had

expected the bird to alight. A friend of mine who was a great naturalist,

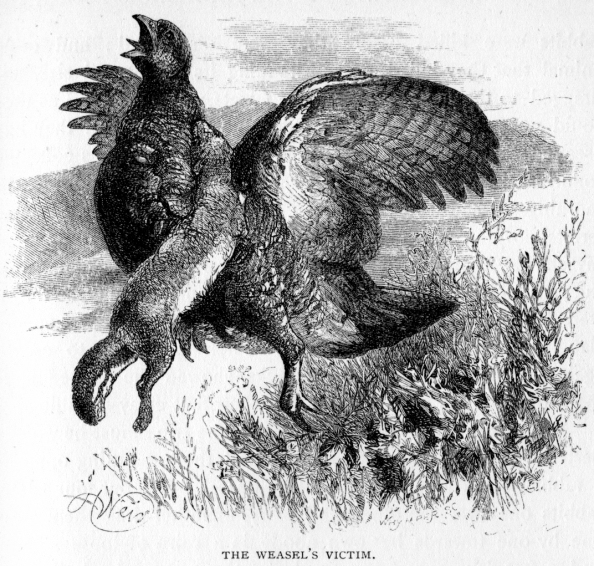

assured me, that, tracking a weasel in snow on the hill-side, he found

where the animal had evidently sprung upon a grouse; and, on carrying on

his observation, he had convinced himself that the bird had flown away

with the quadruped, and had fallen to the ground about thirty yards off,

where he found it with its throat cut; and the tracks of the weasel again

appeared, as if he had come down with the bird, and having sucked its

blood, had gone on its way, looking for a new victim.

The stoat is also very

common here, and equally destructive and sanguinivorous—if I may use such

a word. Being larger, too, he is more mischievous to game and poultry, and

not so useful in killing mice. I often see the stoat hunting in the middle

of an open field : its activity is so great that few dogs can catch it.

When pursued, it dives into any rat's or mole's hole that lies in its way.

I find that a sure mode of driving all animals of this kind out of a hole,

is to smoke tobacco into it. They appear quite unable to stand the smell,

and bolt out immediately in the face of dog or man, rather than put up

with it. Tobacco-smoke will also bring a ferret out of a rabbit-hole, when

everything else fails to do so. In winter the stoat changes its colour to

the purest white, with the exception of the tip of the tail, which always

remains black. The animal is then very beautiful, with its shining black

eyes and white body. The fur is very like that of the ermine, but is quite

useless, owing to the peculiar odour of the animal, which can never be got

rid of. It is worthy of note that the stoat does not emit this odour

excepting when hunted or wounded. When I have shot one, killing it on the

spot, before he has seen me, no smell is to be perceived. The same thing I

have also observed when it has been caught in a large iron trap, which has

killed it instantaneously, before there has been time for fear or

struggling. When, however, I have had some chase after a stoat before

shooting it, or have caught one alive in a trap, the stench of the little

animal is insupportable,— and sticks to the skin, in spite of every

attempt to get rid of it.

The attachment of the stoat

and weasel to their young is very great. I chased a weasel into a hollow

tree : she was carrying some animal in her mouth, and though I was on the

very point of catching her before she got to her refuge, she would not

drop it. I fancied that it was a newly-born rabbit that she was carrying

off. I applied smoke to the hole, and out came the weasel again, still

carrying the same burden. She ran towards a stone wall, but was met by a

terrier half-way, who killed her, catching her with the greater facility

in consequence of her obstinacy in carrying away what I still thought was

some prey. On picking it up, however, I found that it was a young weasel,

unable to run, which its mother was endeavouring to carry to a place of

safety, her former hole in an adjoining field having been ploughed over. I

cannot express my regret at the fate of this poor creature, when I saw

that her death was caused wholly by her maternal affection.

Notwithstanding the havoc which these animals make among my rabbits,

nothing would have induced me to molest her had I known what she was

carrying.

The track of the stoat is

very like that of a young rabbit, and may be easily mistaken for it. They

travel over an amazing extent of ground in their nocturnal rambles, as

their marks in the snow can testify. The edges of rivers and brooks seem

their favourite hunting-places. By some means or other they manage to

catch eels. I tracked a stoat from the edge of a ditch to its own hole, at

the distance of several hundred yards. He had been carrying some heavy

body, as I could plainly see by the marks in the snow; and this, on

digging out the hole, I found to be an eel about nine inches long. No bait

is better for all kinds of the weasel tribe than fish, which they seem to

have a great liking for, and evidently feed upon whenever they inhabit a

neighbourhood where they can procure them.

The polecat is now

comparatively rare in this country, in consequence of the number of

gamekeepers and vermin-trappers : they still, however, frequent the banks

of the river, where they take shelter among the loose stones and rocks.

There is no difference in appearance between the polecat and the brown

ferret, who also partakes very frequently of the shyness of his wild

relative, being much more apt to become cross-tempered and ready to return

to a state of nature than the tamer white ferret. The polecat is extremely

destructive—nothing comes amiss to it. I found in the hole of a she

polecat, besides her young ones, three kittens that had been drowned at

the distance of at least a quarter of a mile. Besides these, her larder

contained the remains of hares, rabbits, and of an infinity of birds and

several eels. There was a wood-pigeon that had young ones nearly

full-grown in an ivy-covered tree close to the window of my dressing-room.

One morning I saw the old birds flying about in distress, but I could see

no hawk or bird of prey about. Presently down fell one of the young birds,

and in a moment afterwards the other young one also fell to the ground,

both bleeding at the throat. Immediately loaded my gun, and had the

satisfaction of shooting a large polecat, who came climbing down the tree

and was just preparing to carry away one of the young pigeons.

Like the stoat, the polecat

has a beautiful fur, rendered useless by the strong odour of the animal.

Notwithstanding the quantity of game and other creatures killed by the

polecat, he does not appear to be very quick on the ground, and must owe

his success in hunting more to perseverance and cunning than to activity.

Like the stoat and weasel, this animal is easily caught in box-traps, and

is attracted in an extraordinary manner by the smell of musk, which they

appear quite unable to resist.

In trapping all these small

beasts with iron traps the bait should be suspended at some little height

above the trap, to oblige them to jump up, and by so doing there is a

better chance that, notwithstanding their light weight, the trap will be

sprung.

Formerly I frequently

mistook the track of the marten-cat for that of a hare, when seen in the

snow. Its way of placing its feet, and of moving by a succession of leaps,

is quite similar to that of the more harmless animal, which so often

serves it for food. The general abode of the marten is in woods and rocky

cairns. He is a very beautiful and graceful animal, with a fine fur, quite

devoid of all smell, but owing to its great agility it must be one of the

most destructive of the tribe. When hunting, their movements are quick and

full of elegance, the effect of which is much heightened by their

brilliant black eyes and rich brown fur, contrasted with the orange-coloured

mark on their throat and breast. The marten, when disturbed by dogs,

climbs a tree with the agility of a squirrel, and leaps from branch to

branch, and from tree to tree. I used frequently to shoot them with my

rifle on the tall pine-trees in Sutherlandshire. In this part of the

country they are now seldom seen. This animal is not wholly carnivorous,

being very fond of some fruits—the strawberry and raspberry, for instance.

I found in my garden in Inverness-shire that some animal came nightly to

the raspberry-bushes; the track appeared like that of a rabbit or hare,

but as I also saw that the animal climbed the bushes, I knew it could be

neither of these. Out of curiosity, I set a trap for the marauder; the

next morning, on going to look at it very early, I could see nothing on

the spot where I had put my trap but a heap of leaves, some dry and some

green; I was just going to move them with my hand, when I luckily

discerned a pair of bright eyes peering sharply out of the leaves, and

discovered that I had caught a large marten, who, finding that he could

not escape, had collected all the leaves within his reach, and had quite

concealed himself under them. The moment he found that he was discovered,

he attacked me most courageously, as the marten always does, fighting to

the last. I had other opportunities of satisfying myself that this animal

is a great fruit-eater, feeding much on the wild raspberries, and even

blackberries, that grow in the woods. Though generally inhabiting cairns

of stones, the marten sometimes takes possession of some large bird's

nest, and, relining it, there brings up her young, who are remarkably

pretty little creatures. I endeavoured once to rear and tame a litter of

young martens which I found in an old crow's nest, and I believe I should

have succeeded had not a terrier got at them in my absence, and revenged

himself on them for the numerous bites he had felt from martens and

polecats in his different encounters with them. I have more frequently

seen this animal abroad during the day-time than any of the other weasels.

I remember starting one

amongst the long heather in the very midst of a pack of dogs of a Highland

fox-hunter : though all the dogs, greyhounds, fox-hounds, and terriers,

were immediately in full pursuit, the nimble little fellow escaped them

all, jumping over one dog, under another, through the legs of a third, and

finally getting off into a rocky cairn, whence he could not be ejected.

"It's the evil speerit hersell," said the old man, as, aiming a blow at

the marten, he nearly broke the back of one of his best lurchers. Nor did

he get over his annoyance at seeing his dogs so completely baffled, till

after many a Gaelic curse at me beast and many a pinch of snuff. The

marten-cat is accused by the shepherds of destroying a great many sheep.

His manner attack is said to be by seizing the unfortunate sheep by the

nose, which he eats away, till the animal is either destroyed on the spot

or dies a lingering death. I have been repeatedly told this by different

Highland shepherds and others, and believe it to be a true accusation.

They kill numbers of lambs, and when they take to poultry-killing, enter

the henhouse fearlessly, committing immense havoc; in fact seldom leaving

a single fowl alive — having the same propensity as the ferret for killing

many more victims than he can consume.

The eagle is said to prey

frequently on the marten-cat, but I never happened to witness an encounter

between them; my tame eagle, however, always seemed to prefer them to any

other food. I have no doubt that the eagle on its native mountain pounces

on any living creature that it can conquer, and therefore must frequently

kill both marten and wild cat, both which animals frequent the rocks and

high ground where this bird hunts.

From the strength and

suppleness of the marten, he cannot fall a very easy prey to any eagle of

this country, and probably when pounced upon he does not die without a

severe battle.

There are said to be two

kinds of martens here, the pine-marten and the beech-marten; the former

having a yellow mark on the breast, and the latter a white one. I do not,

however, believe that they are of a distinct species, but consider the

variety of shade in the colour of the breast to be occasioned by

difference of age or to be merely accidental—having frequently killed them

in the same woods with every intermediate shade from yellow to white on

their breasts, the animals being perfectly alike in every other

particular. The oldest-looking martens had generally a whiter mark than

the others, but this rule did not apply to all.

|