|

The Herring Fisheries - The Lochfyne Fishery - The Pilchard - Herring

Commerce - Mr. Methuen -The Brand - The Herring Harvest - A Night at the

Fishing - The Cure - The Curers - Herring Boats -Increase of Netting -

Are we Overfishing? - Proposal for more Statistics.

Tim fisheries for the common herring, the pilchard, and

the sprat, are carried on, with a brief interval, all the year round; but

the great herring season is during the autumn-from August to October-when

the sea is covered with boats in pursuit of that fine fish, and in some of

its phases the herring-fishery assumes an aspect that is decidedly

picturesque. Every little bay all round the island has its tiny fleet ;

the mountain-closed lochs of the Western Highlands have each a fishery;

while at some of the more important fishing stations there are very large

fleets assembled-as at Wick, Dunbar, Ardrishaig, Stornoway, Peterhead, and

Anstruther. The chief carers have places of business in these towns, where

they keep a large store of curing materials, and a competent staff of

coopers and others to aid them in their business. Such boats as do not

carry on a local fishery proceed from the smaller fishing-villages to one

or other of the centres of the herring trade. In fact, wherever an

enterprising carer sets up his stand, there the boats will gather round

him ; and beside him will collect a crowd of all kinds of miscellaneous

people-dealers in salt, sellers of barrel-staves, vendors of "catch,"

Prussian herring-buyers, comely girls from the inland districts to gut,

and men from the Highlands anxious to officiate as "hired hands."

Itinerant ministers and revivalists also come on the scene and preach

occasional sermons to the hundreds of devout Scotch people who are

assembled ; and thus arises many a prosperous little town, or at least

towns that might be prosperous were the finny treasures of the sea always

plentiful. As the chief herring season comes on a kind of madness seizes

on all engaged, ever so remotely, in the trade; as for those more

immediately concerned, they seem to go completely "daft," especially the

younger hands. The old men, too, copse outside to view the annual

preparations, and talk, with revived enthusiasm, to their sons and

grandsons about what they did twenty years agone; the young men spread out

the shoulder-of-mutton sails of their boats to view and repair defects;

and the wives and sweethearts, by patching and darning, contrive to make

old nets "look amaist as weel as new;" boilers bubble with the brown

catechu, locally called "catch," which is used as a preservative for

the nets and sails; while all along the coasts old boats are being cobbled

up, and new ones are being built and launched.

The scene along the Scotch seaboard from Buckhaven to

Buckie is one of active preparation, and all concerned are hoping for a

"lucky" fishing; "winsome" young lassies are praying for the success of

their sweethearts' boats, because if the season turns out well they will

be married women at its close. Curers look sanguine, and the owners of

free boats seem happy. The little children too-those wonderful little

children one always finds in a fishing village, striving so manfully to

fill up "daddy's" old clothes-participate in the excitement: they have

their winter's "shoon" and "Sunday breeks" in perspective. At the quaint

village of Gamrie, at Macduff, or Buckie, the talk of old and young, on

coach or rail, from morning to night, is of herrings. There are

comparisons and calculations about "craps" and barrels, and "broke" and "splitbellies,"

and "full fish" and "links," and reminiscences of great hauls of former

years, and much figurative talk about prices and freights, and the cost of

telegraphic messages. Then, if the present fishery be dull, hopes are

expressed that the next one may be better. "Ony fish this mornin' ?" is

the first salutation of one neighbour to another : the very infants talk

about "herrin' ;" schoolboys steal them from the boats for the purpose of

aiding their negotiations with the gooseberry woman; while wandering

paupers are rewarded with one or two broken fish by good-natured fishers,

when "the take" has been so satisfactory as to warrant such largess. At

Wick the native population, augmented by four thousand strangers, wakens

into renewed life; it is like Doncaster on the approach of the St. Leger.

The summer-time of Wick's existence begins with the fishery: the shops are

painted on their outsides and are replenished within; the milliner and the

tailor exhibit their newest fashions; the hardware merchant flourishes his

most attractive frying-pans; the grocer amplifies his stock; and so for a

brief period all is couleur de rose.

They are not all practical fishermen who go down to the

sea for herring during the great autumnal fishing season. By far the

larger portion of those engaged in the capture of this fish - particularly

at the chief stations-are what are called "hired hands," a mixture of the

farmer, the mechanic, and the sailor; and this fact may account in some

degree for a portion of the accidents which are sure to occur in stormy

seasons. Many of these men are mere labourers at the herring fishery, and

have little skill in handling a boat; they are many of them farmers in the

Lewis, or, small crofters in the Isle of Skye. The real orthodox fisherman

is a different being, and he is the same everywhere. If you travel from

Banff to Bayonne you find that fishermen are unchangeable.

The men's work is all performed at sea, and, so far as

the capture of the herring is concerned, there is no display of either

skill or cunning. The legal mode of capturing the herring is to take it by

means of what is called a drift-net. The herringfishery, it must be borne

in mind, is regulated by Act of Parliament, by which the exact means and

mode of capture are explicitly laid down. A drift-net is an instrument

made of fine twine worked into a series of squares, each of which is an

inch, so as to allow plenty of room for the escape of young herrings. Nets

for herring are measured by the barrel-bulk, and each barrel will hold two

nets, each net being fifty yards long and thirty-two feet deep. The larger

fishing-boats carry something like a mile of these nets; some, at any

rate, carry a drift which will extend two thousand yards in length. These

drifts are composed of many separate nets, fastened together by means of

what is called a back-rope, and each separate net of the series is marked

off by a buoy or bladder which is attached to it, the whole being sunk in

the sea by means of a leaden or other weight, and fastened to the boat by

a longer or shorter trail-rope, according to the depth in the water at

which it is expected to find the herrings. This formidable apparatus,

which forms a great perforated wall, being let into the sea immediately

after sunset, floats or drifts with the tide, so as to afford the herring

an opportunity of striking against it, and so becoming captured-in fact

they are drowned in the nets. The boats engaged in the drift-net fishing

are of various sizes, and are strongly and carefully built: the largest,

being upwards of thirty-five feet keel, with a large drift of nets and

good sail and mast, will cost something like a sum of £300. The other mode

of fishing for herrings, which has existed for about a quarter of a

century, is known as trawling. In the west of Scotland, on Lochfyne in

particular, where it is practised, it is called "trawling ;" but the

instrument of capture is in reality a" seine " net ; and, so far as the

size of the mesh is concerned, is all right.

The pilchard is generally captured by means of the

seine-net, and we never hear of its being injured thereby. It is also

cured in large quantities, the same as the herring, although the modus

operandi is somewhat different. The pilchard was at one time, like the

herring, thought to be a migratory fish, but it has been found, as in the

case of the common herring, to be a native of our own seas. In some years

the pilchard has been known to shed its spawn in May, but the usual time

is October. Their food is small crustaceous animals, as their stomachs are

frequently crammed with a small kind of shrimp, and the supply of this

kind of food is thought to be enormous. When on the coast, the assemblage

of pilchards assumes an arrangement like that of a great army, and the

vast shoal is known to be made up by the coming together of smaller bodies

of that fish, and these frequently separate and rejoin, and are constantly

shifting their position. The pilchard is not now so numerous as it was a

few years ago, but very large hauls are still occasionally obtained.

Great excitement prevails on the coast of Cornwall

during the pilchard season. Persons watch the water from the coast, and

signal to those who are in search of the fish the moment they perceive

indications of a shoal. These watchers are locally called "huers," and

they are provided with signals of white calico or branches of trees, with

which to direct the course of the boat, and to inform those in charge when

they are upon the fish-the shoal being best seen from the cliffs. The

pilchards are captured by the seine-net-that is, the shoal, or spot of a

shoal, that has risen, is completely surrounded by a wall of netting, the

principal boat and its satellites the volyer and the lurker, with the "

stop-nets," having so worked as quite to overlap each other's wall of

canvas. The place where the joining of the two nets is formed is carefully

watched, to see that none of the fish escape at that place, and if it be

too open, the fish are beaten back with the oars of some of the persons

attending-about eighteen in all. In due time the seine is worked or hauled

into shallow water for the convenience of getting out the fish, and it may

perhaps contain pilchards sufficient to fill two thousand hogsheads.

Generally speaking, four or five seines will be at work together, giving

employment to a great number of the people, who may have been watching for

the chance during many days. When the tide falls the men commence to bring

ashore the fish, a tuck-net worked inside of the seine being used for

safety ; and the large shallow dipper boats required for bringing the fish

to the beach may be seen sunk to the water's edge with their burden, as

successive bucketfuls are taken out of the nets and emptied into these

conveyance vessels. To give the reader an idea of quantity, as connected

with pilchard-fishing, I may state that it takes nearly three thousand

fish to fill a hogshead. I have heard of a shoal being captured that took

a fortnight to bring ashore.

Ten thousand hogsheads of pilchards have been known to

be taken in one port in a day's time. The convenience of keeping the shoal

in the water is obvious, as the fish need not be withdrawn from it till it

is convenient to salt them. The fish are salted in curing-houses, great

quantities of them being piled up into huge stacks, alternate layers of

salt and fish. During the process of curing a large quantity of useful oil

exudes from the heaps. The salting process is called " bulking," and the

fish are built up into stacks with great regularity, where they are

allowed to remain for four weeks, after which they are washed and freed

from the oil, then packed into hogsheads, and sent to Spain and Italy, to

be extensively consumed during Lent, as well as at other fasting times.

The hurry and bustle at any of the little Cornwall ports during the

manipulation of a few shoals of pilchards must be seen, the excitement

cannot be very well described. The pilchard is, or rather it ought to be,

the Sardinia of commerce, but its place is usurped by the sprat, or

garvie as we call it in Scotland, and thousands of tin boxes of that fish

are annually made up and sold as sardines. I have already alluded to the

sprat, so far as its natural history is concerned. It is a fish that is

very abundant in Scotland, especially in the Firth of Forth, where for

many years there has been a good sprat-fishery. We do not now require to

go to France for our sardines, as we can cure them at home in the French

style.

Sprats, whether they be young herrings or no, are very

plentiful in the winter months, and afford a supply of wholesome food of

the fish kind to many who are unable to procure more expensive kinds. When

the fishing for garvies (sprats) was stopped a few years ago

by order of the Board of White Fisheries, there was

quite a sensation in Edinburgh; and an agitation was got up that

has resulted in a partial resumption of the fishing, which is of

considerable value-about £50,000 in the Firth of Forth alone.

Commerce in herring is entirely

different from commerce in any other article, particularly in Scotland. In

fact the fishery, as at present conducted, is just another way of

gambling. The home "curers" and foreign buyers are the persons who at

present keep the herring-fishery from stagnating, and the goods (i.e. the

fish) are generally all bought and sold long before they are captured. The

way of dealing in herring is pretty much as follows: - Owners of boats are

engaged to fish by curers, the bargains being usually that the curer will

take two hundred crans of herring - and a cran, it may be stated, is

forty-five gallons of ungutted fish; for these two hundred crans a certain

sum per cran is paid according to arrangement, the bargain including as

well a definite sum of ready money by way of bounty, perhaps also an

allowance of spirits, and the use of ground for the drying of the nets. On

the other hand, the boat-owner provides a boat, nets, buoys, and all the

apparatus of the fishery, and engages a crew to fish ; his crew may,

perhaps, be relatives and part-owners sharing the venture with him, but

usually the crew consists of hired men who get so much wages at the end of

the season, and have no risk or profit. This is the plan followed by free

and independent fishermen who are really owners of their own boats' and

apparatus. It will thus be seen that the curer is bargaining for two

hundred crans of fish months before he knows that a single herring will be

captured ; for the bargain of next season is always made at the close of

the present one, and he has to pay out at once a large sum by way of

bounty, and provide barrels, salt, and other necessaries for the cure

before he knows even if the catch of the season just expiring will all be

sold, or how the markets will pulsate next year. On the other hand, the

fisherman has received his pay for his season's fish, and very likely

pocketed a sum of from ten to thirty pounds as earnest-money for next

year's work. Then, again, a certain number of curers, who are men of

capital, will advance money to young fishermen in order that they may

purchase a boat and the necessary quantity of netting to enable them to

engage in the fishery - thus thirling the boat to their service, very

probably fixing an advantageous price per cran for the herrings to be

fished and supplied. Curers, again, who are not capitalists, have to

borrow from the buyers, because to compete with their fellows they must be

able to lend money for the purchase of boats and nets, or to advance sums

by way of bounty to the free boats ; and thus a rotten unwholesome system

goes the round-fishermen, boat-builders, curers, and merchants, all

hanging on each other, and evidencing that there is as much gambling in

herring-fishing as in horse-racing. The whole system of commerce connected

with this trade is decidedly unhealthy, and ought at once to be checked

and reconstructed if there be any logical method of doing it. At a port of

three hundred boats a sum of £145 was paid by the curers for "arles," and

spent in the public-houses ! More than S4000 was paid in bounties, and an

advance of nearly £7000 made on the various contracts, and all this money

was paid eight months before the fishing began. When the season is a

favourable one, and plenty of fish are taken, then all goes well, and the

evil day is postponed; but if, as in one or two recent seasons, the take

is poor, then there comes a crash. One falls, and, like a row of bricks,

the others all follow. At the large fishing stations there are

comparatively few of the boats that are thoroughly free; they are tied up

in some way between the buyers and curers, or they are in pawn to some

merchant who " backs " the nominal owner. The principal, or at least the

immediate sufferers by these arrangements are the hired men.

This "bounty," as it is called, is a most reprehensible

feature of herring commerce, and although still the prevalent mode of

doing business, has been loudly declaimed against by all who have the real

good of the fishermen at heart. Often enough men who have obtained boats

and nets on credit, and hired persons to assist them during the fishery,

are so unfortunate as not to catch enough of herrings to pay their

expenses. The curers for whom they engaged to fish having retained most of

the bounty money on account of boats and nets, consequently the hired

servants have frequently in such cases to go home -sometimes to a great

distance-penniless. It would be much better if the old system of a share

were re-introduced : in that case the hired men would at least participate

to the extent of the fishing, whether it were good or bad. Boat-owners try

of course to get as good terms as possible, as well in the shape of price

for herrings as in bounty and perquisites. My idea is that there ought to

be no " engagements," no bounty, and no perquisites. As each fishing comes

round let the boats catch, and the curers buy day by day as the fish

arrive at the quay. This plan has already been adopted at some

fishing-towns, and is an obvious improvement on the prevailing plan of

gambling by means of "engagements" in advance.

In fact, this fishery is best described when it is

called a lottery. No person knows what the yield will be till the last

moment : it may be abundant, or it may be a total failure, Agriculturists

are aware long before the reaping season whether their crops are light or

heavy, and they arrange accordingly ; but if we are to believe the

fishermen, his harvest is entirely a matter of "luck." It is this belief

in "luck" which is, in a great degree, the cause of our fisher-folk not

keeping pace with the times: they are greatly behind in all matters of

progress; our fishing towns look as if they were, so to speak,

stereotyped. It is a woeful time for the fisher-folk when the herrings

fail them ; for this great harvest of the sea, which needs no tillage of

the husbandman, the fruits of which are reaped without either sowing seed

or paying rent, is the chief industry that the bulk of the coast

population depend upon for a good sum of money. The fishing is the bank,

in which they have opened, and perhaps exhausted, a cash-credit; for often

enough the balance is on the wrong side of the ledger, even after the

fishing season has come and gone. In other words, new boats have to be

paid for out of the fishing; new clothes, new houses, additional nets, and

even weddings, are all dependent on the herring-fishery. It is notable

that after a favourable season the weddings among the fishing populations

are very numerous. The anxiety for a good season may be noted all along

the British coasts, from Newhaven to Yarmouth, or from Crail to Wick.

The highest prices are paid for the early fish,

contracts for these in a cured state being sometimes fixed as high as

forty-five shillings per barrel. These are at once despatched to Germany,

in the inland towns of which a prime salt herring of the early cure is

considered a great luxury, fetching sometimes the handsome price of one

shilling ! Great quantities of cured herrings are sent to Stettin or other

German ports, and so eager are some of the merchants for an early supply

that in the beginning of the season they purchase quantities unbranded,

through! the agency of the telegraph. On those parts of the

coast where the communication with large towns is easy, considerable

quantities of herring are purchased fresh, for transmission to Birmingham,

Manchester, and other inland cities. Buyers attend for that purpose, and

send them off frequently in an open truck, with only a slight covering to

protect them from the sun. It is needless to say that a fresh herring is

looked upon as a luxury in such places, and a demand exists that would

exhaust any supply that could be sent.

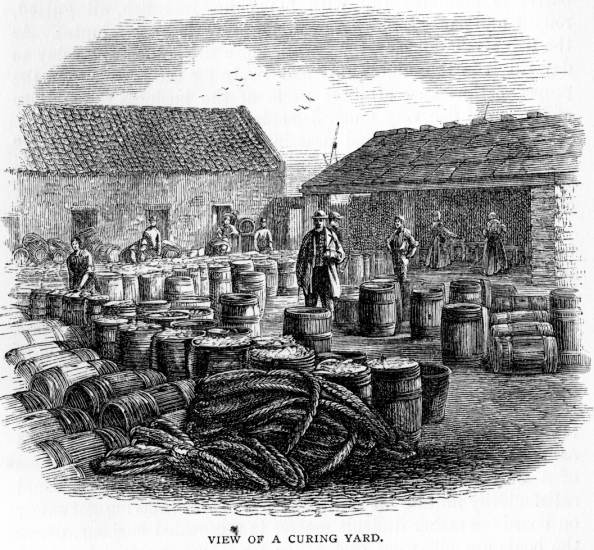

Having explained the relation of the curers to the

trade, I must now speak of the cure-the greater number of the herrings

caught on the coast of Scotland being pickled in salt ; a result

originally, no doubt, of the want of speedy modes of transit to large

seats of population, where herrings would be largely consumed if they

could arrive in a sufficiently fresh state to be palatable. At stations

about Wick the quantity of herrings disposed of fresh is comparatively

small, so that by far the larger portion of the daily catch has to be

salted. This process during a good season employs a very large number of

persons, chiefly as coopers and gutters ; and, as the barrels have to be

branded, by way of certificate of the quality of their contents, it is

necessary that the salting should be carefully done. As soon as the

boats reach the harbour - and as the fishing is appointed

to be carried on after sunset they arrive very early in the morning - the

various crews commence to carry their fish to the reception-troughs of the

curers by whom they have been engaged. A person in the interest of the

curer checks the number of crans brought in, and sprinkles the fish from

time to time with considerable quantities of salt. As soon as a score or

two of baskets have been emptied, the gutters set earnestly to do their

portion of the work, which is dirty and disagreeable in the extreme. The

gutters usually work in companies of about five-one or two gutting, one or

two carrying, and another packing. Basketfuls

of the fish, so soon as they are gutted, are carried to

the back of the yard, and plunged into a large tub, there to be roused and

mixed up with salt ; then the adroit and active packer seizes a handful

and arranges them with the greatest precision in a barrel, a handful of

salt being thrown over each layer as it is put in, so that, in the short

space of a few minutes, the large barrel is crammed full with many hundred

fish, all gutted, roused, and packed, in a period of not more than ten

minutes. As the fish settle down in the barrel, more are added from day to

day till it is thoroughly full and ready for the brand. On the proper

performance of these parts of the business the quality of the cured fish

very much depends.The

following detailed description of the "herring-harvest," as gathered in

the Moray Firth, may be of interest to the general reader. It is

reprinted, by permission, from a paper contributed by the author to the

Cornhill Magazine :

The boats usually start for the

fishing-ground an hour or two before sunset, and are generally manned by

four men and a boy, in addition to the owner or skipper. The nets, which

have been carried inland in the morning, in order that they might be

thoroughly dried, have been brought to the boat in a cart or waggon. On

board there is a keg of water and a bag of bread or hard biscuit; and in

addition to these simple necessaries, our boat contains a bottle of whisky

which we have presented by way of paying our footing. The name of our

skipper is Francis Sinclair, and a very gallant-looking fellow he is ; and

as to his dress-why, his boots alone would ensure the success of a Surrey

melodrama; and neither Truefit nor Ross could satisfactorily imitate his

beard and whiskers. Having got safely on board-a rather difficult matter

in a crowded harbour, where the boats are elbowing each other for room-we

contrive, with some labour, to work our way out of the narrow-necked

harbour into the bay, along with the nine hundred and ninety-nine boats

that are to accompany us in our night's avocation. The heights of

Pulteneytown, which commands the quays, are covered with spectators

admiring the pour-out of the herring fleet and wishing with all their

hearts " God speed " to the venturers ; old salts who have long retired

from active seamanship are counting their " takes " over again ; and the

curer is mentally reckoning up the morrow's catch. Janet and Jeanie are

smiling a kindly good-bye to " faither," and hoping for the safe return of

Donald or Murdoch; and crowds of people are scattered on the heights, all

taking various degrees of interest in the scene, which is stirringly

picturesque to the eye of the tourist, and suggestive to the thoughtful

observer.

Bounding gaily over the waves, which

are crisping and curling their crests under the influence of the

land-breeze, our shoulder-of-mutton sail filled with a good capful of

wind, we hug the rocky coast, passing the ruined tower known as "the Old

Man of Wick," which serves as a capital landmark for the fleet. Soon the

red sun begins to dip into the golden west, burnishing the waves with

lustrous crimson and silver, and against the darkening eastern sky the

thousand sails of the herring-fleet blaze like sheets of flame. The shore

becomes more and more indistinct, and the beetling cliffs assume fantastic

and weird shapes, whilst the moaning waters rush into deep cavernous

recesses with a wild and monotonous sough, that falls on the ear with a

deeper and a deeper melancholy, broken only by the shrill wail of the

herring-gull. A dull hot haze settles on the scene, through which the

coppery rays of the sun penetrate, powerless to cast a shadow. The scene

grows more and more picturesque as the glowing sails of the fleet fade

into grey specks dimly seen. Anon the breeze freshens and our boat cleaves

the water with redoubled speed : we seem to sail farther and farther into

the gloom, until the boundary-line between sea and shore becomes lost to

the sight.

We ought to have shot our nets

before it became so dark, but our skipper, being anxious to hit upon the

right place, so as to save a second shooting, tacked up and down,

uncertain where to take up his station. We had studied the movements of

certain "wise men" of the fishery-men who are always lucky, and who find

out the fish when others fail; but our crew became impatient when they

began to smell the water, which had an oily gleam upon it indicative of

herring, and sent out from the bows of the boat bright phosphorescent

sparkles of light. The men several times thought they were right over the

fish, but the skipper knew better. At last, after a lengthened cruise, our

commander, who had been silent for half-an-hour, jumped up and called to

action. "Up, men, and at 'em," was then the order of the night. The

preparations for shooting the nets at once began by our lowering sail.

Surrounding us on all sides was to be seen a moving world of boats ; many

with their sails down, their nets floating in the water, and their crews

at rest, indulging in fitful snatches of sleep. Other boats again were

still flitting uneasily about; their skippers, like our own, anxious to

shoot in the best place, but as yet uncertain where to cast: they wait

till they see indications of fish in other nets. By and by we are

ourselves ready, the sinker goes splash into the water, the "dog" (a large

bladder, or inflated skin of some kind, to mark the far end of the train)

is heaved overboard, and the nets, breadth after breadth, follow as fast

as the men can pay them out (each division being marked by a large painted

bladder), till the immense train sinks into the water, forming a

perforated wall a mile long and many feet in depth; the "dog" and the

marking bladders floating and dipping in a long zigzag line, reminding one

of the imaginary coils of the great sea-serpent.

Wrapped in the folds of a sail and

rocked by the heaving waves we tried in vain to snatch a brief nap, though

those who are accustomed to such beds can sleep well enough in a

herringboat. The skipper, too, slept with one eye open; for the boat being

his property, and the risk all his, he required to look about him, as the

nets are apt to become entangled with those belonging to other fishermen,

or to be torn away by surrounding boats. After three hours' quietude,

beneath a beautiful sky, the stars

" Those eternal orbs that beautify

the night "

began to pale their fires, and the

grey dawn appearing indicated that it was time to take stock. On reckoning

up we found that we had floated gently with the tide till we were a long

distance away from the harbour. The skipper had a presentiment that there

were fish in his nets; indeed the bobbing down of a few of the bladders

had made it almost a certainty; at any rate we resolved to examine the

drift, and see if there were any fish. It was a moment of suspense, while,

by means of the swing-rope, the boat was hauled up to the nets. "Hurrah!"

at last exclaimed Murdoch of the Isle of Skye, "there's a lot of fish,

skipper, and no mistake." Murdoch's news was true ; our nets were silvery

with herrings-so laden, in fact, that it took a long time to haul them in.

It was a beautiful sight to see the shimmering fish as they came up like a

sheet of silver from the water, each uttering a weak death-chirp as it was

flung to the bottom of the boat. Formerly the fish were left in the meshes

of the nets till the boat arrived in the harbour ; but now, as the net is

hauled on board, they are at once shaken out. As our silvery treasure

showers into the boat we roughly guess our capture at fifty crans - a

capital night's work.

The herrings being all on board, our

duty is now to "up sail " and get home : the herrings cannot be too soon

among the salt. As we make for the harbour, we discern at once how rightly

the term lottery has been applied to the herring-fishery, Boats which

fished quite near our own were empty; while others again greatly exceeded

our catch. "It is entirely chance work," said our skipper; "and although

there may sometimes be millions of fish in the bay, the whole fleet may

not divide a hundred crans between them." On some occasions, however, the

shoal is hit so exactly that the fleet may bring into the harbour a

quantity of fish that in the gross would be an ample fortune. So heavy are

the "takes " occasionally, that we have known the nets of many boats to be

torn away and lost through the sheer weight of the fish which were

enmeshed in them.

The favouring breeze soon carried us

to the quay, where the boats were already arriving in hundreds, and where

we were warmly welcomed by the wife of our skipper, who bestowed on us, as

the lucky cause of the miraculous draught, a very pleasant smile. When we

arrived the cure was going on with startling rapidity. The night had been

a golden one for the fishers - calm and beautiful, the water being merely

rippled by the land-breeze. But it is not always so in the Bay of Wick ;

the herring-fleet has been more than once overtaken by a fierce storm,

when valuable lives have been lost, and thousands of pounds' worth of

netting and boats destroyed. On such occasions the gladdening sights of

the herring-fishery are changed to wailing and sorrow. It is no wonder

that the heavens are eagerly scanned as the boats marshal their way out of

the harbour, and the speck on the distant horizon keenly watched as it

grows into a mass of gloomy clouds. As the song says, "Caller herrin' "

represent the lives of men ; and many a despairing wife and mother can

tell a sad tale of the havoc created by the summer gales on our exposed

northern coast.

From the heights of Pulteneytown,

overlooking the quays and curers' stations, one has before him, as it

were, an extended plain, covered with thousands and tens of thousands of

barrels, interspersed at short distances with the busy scene of delivery,

of packing, and of salting, and all the bustle and detail attendant on the

cure. It is a scene difficult to describe, and has ever struck those

witnessing it for the first time with wonder and surprise.

Having visited Wick in the very heat

of the season, and for the express purpose of gaining correct information

about this important branch of our national industry, I am enabled to

offer a slight description of the place and its appurtenances. Travellers

by the steamboat usually arrive at the very time the "herring-drave" is

making for the harbour; and a beautiful sight it is to see the magnificent

fleet of boats belonging to the district, radiant in the light of the

rising sun, all steadily steering to the one point, ready to add a large

quota to the wealth of industrial Scotland. As we wend our way from the

little jagged rock at which we are landed by the small boat attendant on

the steamer, we obtain a glimpse of the one distinguishing feature of the

town-the herring commerce. On all sides we are surrounded by herring. On

our left hand countless basketfuls are being poured into the immense

gutting-troughs, and on the right hand there are countless basketfuls

being carried from the three or four hundred boats which are ranged on

that particular side of the harbour; and behind the troughs more

basketfuls are being carried to the packers. The very infants are seen

studying the " gentle art;" and a little mob of breechless boys are busy

hooking up the silly "poddlies." All around the atmosphere is humid ; the

sailors are dripping, the herring-gutters and packers are dripping, and

every thing and person appears wet and comfortless ; and as you pace along

you are nearly ankle-deep in brine. Meantime the herrings are being

shovelled about in the large shallow troughs with immense wooden spades,

and with very little ceremony. Brawny men pour them from baskets on their

shoulders into the aforesaid troughs, and other brawny men dash them about

with more wooden spades, and then sprinkle salt over each new parcel as it

is poured in, till there is a sufficient quantity to warrant the

commencement of the important operation of gutting and packing. Men are

rushing wildly about with note-books, making mysterious-looking entries.

Carts are being filled with dripping nets ready to hurry them off to the

fields to dry. The screeching of saws among billet-wood, and the plashing

of the neighbouring water-wheel, add to the great babel of sound that

deafens you on every side. Flying about, blood-bespattered and hideously

picturesque, we observe the gutters ; and on all hands we may note

thousands of herring-barrels, and piles of billet-wood ready to convert

into staves At first sight every person looks mad-some appear so from

their costume, others from their manner-and the confusion seems

inextricable; but there is method in their madness, and even out of the

chaos of Wick harbour comes regularity, as I have endeavoured to show.

So soon as a sufficient quantity of

fish has been brought from the boats and emptied into the gutting troughs,

another of the great scenes commences - viz, the process of evisceration,

This is performed by females, hundreds of whom annually find wellpaid

occupation at the gutting-troughs. It is a bloody business ; and the

gaily-dressed and dashing females whom we had observed lounging about the

curing yards, waiting for the arrival of the fish, are soon most

wonderfully transmogrified. They of course put on a suit of apparel

adapted to the business they have in hand-generally of oil-skin, and often

much worn. Behold them, then, about ten or eleven o'clock in the forenoon,

when the gutting scene is at its height, and after they have been at work

for an hour or so : their hands, their necks, their busts, their

"Dreadful faces throng'd, and fiery

arms "

their every bit about them, fore and

aft, are spotted and besprinkled o'er with little scarlet clots of gills

and guts; or, as Southey says of Don Roderick, after the last and fatal

fight

" Their flanks incarnadined,

Their poitral smear'd with Mood "

See yonder trough, surrounded by a

score of fierce eviscerators, two of them wearing the badge of widowhood !

How deftly they ply the knife ! It is ever a bob down to seize a herring,

and a bob up to throw it into the basket, and the operation is over. It is

performed with lightning-like rapidity by a mere turn of the hand, and

thirty or forty fish are operated upon before you have time to note sixty

ticks of your watch. These ruthless widows seize upon the dead herrings

with such a fierceness as almost to denote revenge for their husbands'

deaths ; for they, alas ! fell victims to the herring lottery, and the

widows scatter about the gills and guts as if they had no bowels of

compassion.

In addition to herrings that are

pickled and those sold in a fresh state, great numbers are made into what

are called " bloaters," or transformed into " reds." At Yarmouth, immense

quantities of bloaters and reds are annually prepared for the English

markets. The bloaters are very slightly cured and as slightly smoked,

being prepared for immediate sale ; but the herrings brought into Yarmouth

are cured in various ways: the

bloaters are for quick sale and speedy consumption ;

then there is a special cure for fish sent to the Mediterranean-"

Straitsmen " I think these are called ; then there are the black herrings,

which have a really fine flavour. In fact the Yarmouth herrings are so

cured as to be suitable to particular markets. It may interest the general

reader to know that the name of "bloater" is derived from the herring

beginning to swell or bloat during the process of curing. Small logs f oak

are burned to produce the smoke, and the fish are all put on "spits" which

are run through the gills. The " spitters " of Yarmouth are quite as

dexterous as the gutters of Wick, 4 woman being able to spit a last per

day. Like the gutters and packers of Wick, the spitters of Yarmouth work

in gangs. The fish, after being hung and smoked, are packed in barrels,

each containing seven hundred and fifty fish.

The Yarmouth boats do not return to harbour every

morning, like the Scotch boats; being decked vessels of some size, from

fifty to eighty tons, costing about £1000, and having stowage for about

fifty lasts of herrings, they are enabled to remain at sea for some days,

usually from three to six, and of course they are able to use their small

boats in the fishery, a man or two being left in charge of the large

vessel, while the majority of the hands are out in the boats fishing.

There has always been a busy herring-fishery at the port of Yarmouth. A

century ago upwards of two hundred vessels were fitted out for the

herring-fishery, and these afforded employment to a large number of

people-as many as six thousand being employed in one way or the other in

connection with the fishery. The Yarmouth boats or busses are not unlike

the boats once used in Scotland, which have been already described. They

carry from fifteen to twenty lasts of herrings (a last, counted

fisher-wise, is more than 13,000 herrings, but nominally it is 10,000

fish), and are manned with some fourteen men or boys.

The following summary of the official statistics issued

by the Board for the fishing of 1872

will give the reader an idea of the present

state of this important industry. The information laid before Parliament

about the capture and branding of herrings during the year 1872 is fuller

than usual, and is of more than usual interest, setting forth as it does

the increasing value which is attached by curers to the brand, and giving

at the same time a series of minute details of the great improvement

annually being effected in the construction of fishing boats and the

increase of the number. The Fishery Board can only take cognizance of the

herrings which are cured (i.e. salted), as no machinery exists for

tabulating those quantities which are sold "fresh," but it would not,

perhaps, be an exaggeration to consider the quantities of the latter as

being equal to the number cured, which was last year 773,859 barrels, as

against 825,475 barrels in 1871. Calculating, in a rough way, each barrel

to contain 800 fish, that would give a total of 619,087,200 cured

herrings, while that number doubled might give a tolerable approximation

of the total capture of herrings on the coast of Scotland. As regards the

numbers captured off the Isle of Man, at Yarmouth, and other English

fisheries, we have no authentic information-no statistics being taken of

the English herring or other fisheries. The following figures denote the

quantities of herrings which have been cured in Scotland

during the last six years-a period which

affords a very fair idea of the fluctuations incidental to this fishery:

|

Year |

Barrels |

|

Year |

Barrels |

|

1867 |

825,589 |

1870 |

833,160 |

|

1868 |

651,433 |

1871 |

825,475 |

|

1869 |

675,143 |

1872 |

773,859 |

The Commissioners state that, at the rate of 4d. per

barrel a sum of 17045 : 10 : 6 was derived in 1872 from the exercise of

the brand, which is the largest amount yet obtained in any one year since

payments for branding were exacted. For branding portions of the take of

the above six years a sum of £30,669 : 4 : 2 was taken by the Board;

which, as the payment of fees is not compulsory, shows that the brand, as

an official certificate of cure, is greatly appreciated by a considerable

body of the Scottish curers; the number of barrels branded last year being

422,731, or more than half of the quantity which was cured. It is

estimated by the Commissioners that the fees taken for branding yielded in

1872 a profit to the Government of X3765. As already stated the quantity

of herrings cured in 1872 was 773,859 barrels, and of these, as has been

shown, 422,731 barrels were branded, a proportion which is larger than

that of any preceding year, and proves, say the Commissioners, "the care

with which the herrings were selected for market." The Commissioners also

say that, "considering the great extent of the herring fishery, that it is

carried on at night, the rough weather to which the boats are often

exposed, the unavoidable hurry with which they are unloaded to get the

fish into the curing stations as soon as possible after they are

caught-the number of mixed hands then put upon them to gut and pack, and

the rapidity with which that work has to be done, it speaks well for the

existing organisation of the fisheries of Scotland that 54 per cent of the

total cure, or more than one half, should have reached the high standard

required by the Board." Another feature which is brought out by the

Commissioners in connection with the brand is, that the quantity branded

this year bears an unusual proportion to the quantity exported, which was

549,631 barrels; showing that only 126,900 barrels were exported which

were not branded, a number which, though it may seem considerable, is

small when analysed; for it includes ungutted fish, also the export to

Ireland, which consists for the most part of fish not originally selected

for first-class cure ; also the greater part of the fish from the early

herring fishery of the Hebrides prepared for immediate sale. In short, the

quantity exported is 71 per cent of the quantity cured, and the quantity

branded is 77 per cent of the quantity exported, thus showing that more

than three-fourths of the export trade consists of branded herrings. The

highest years of branding previous to 1872 were the years 1820, 1862, and

1871. The branding in these years was:- In 1820, 363,872 barrels; in 1862,

346,712 barrels; in 1871, 346,663 barrels; in 1872, 422,731 barrels. The

branding of 1872 has therefore exceeded the branding of 1820 by 58,859

barrels, equal to 16 per cent of increase, and has exceeded the branding

of 1862 by 76,019 barrels, and of 1871 by 76,098 barrels, equal in each of

these years to 22 per cent of increase. In this comparison it is to be

remarked further, that the year 1820 includes brandings at stations in

England, and that the brand was given at that time not only without the

charge of a fee, but with a bounty upon it paid by the Government ; a

bounty which amounted for the year 1820 to upwards of £72,000. It is

therefore remarkable to see Scotland alone, without England, and without

the stimulus of a bounty, relieving Government by an annual payment which

could reach in a year £72,000, and substituting instead a return from

branding which has already paid to Government upwards of £63,000, and

which yielded as its collection in 1872 the sum of £7045 : 10: 6.

An improved order of fishing boat has of late come

prominently into use in the Scottish herring-fishery. Decked boats are now

coming greatly into use, and in time will entirely supplant the

old-fashioned open boats. Upon the east coast particularly, nearly every

new boat now built is bigger than the one it displaces, and although the

decked vessels cost much more money than the open boats, the return which

they yield is commensurate with the cost. At some fishing places the gains

of those crews fishing with decked vessels ranged in 1872 from £100 to

£550 per boat, while the money taken by other crews about the same place

who fished with open boats did not exceed £160, that being the highest

amount reached, some crews only realising £60 for their season's

adventure. The decked boats cost about £200 each, and it is thought by the

builders that there will not be less than 600 of this class of vessels at

work in the fishery of this year. Already at Buckie, on the Banffshire

coast, there are 400 such vessels engaged in the fishing, and in every

important fishery district the boatbuilders are at work adding to the

fleet. "No fisherman would now," say the Commissioners, "undertake fishing

with boats and nets of the kind which were in use a century ago, and the

increase in the number of boats and fishermen during the last ten years

yields conclusive evidence of the steadily advancing prosperity of the

Scottish fisheries. We gather from the current report that the number of

fishing boats belonging to Scotland in 1862 was 12,545, and that, in the

ten years which have elapsed since, that number has increased at the rate

of 260 boats per annum, and the total number of Scottish boats now engaged

in the fisheries is 15,232. In 1862 the number of fishermen in Scotland

was 41,008, but the number now is 46,178, being an increase in ten years

of 5170 fishermen, or an average of 500 per year. The value of the boats

and fishing gear was estimated in the year 1862 at £747,794, and in 1872

at £997,293, being an increase in ten years of £249,499, equal to an

annual average of about £25,000. "In boats, and in the condition of the

fishermen, the fisheries of Scotland may therefore be regarded as

thriving."

As to the takes of herring at the different fishing

districts, the report of the fishery of 1872 records the usual

fluctuations - an increase in one district, a decline in another. At

Fraserburgh and Peterhead the fishing of 1872 was remarkably successful,

as also at Aberdeen, where the fishery is only of recent development. At

these places larger quantities of herring were cured last year than ever

were cured before. Upon the west coast the fishing was again deficient,

the Lewes fishery being far less productive than in former seasons. At

Campbeltown the fishery was very prolific, the fishing of 1872 being the

most successful of any year of which there is a record in the district.

The winter herring fishery of the Firth of Forth was very deficient in

productiveness, but the sprat fishery proved only too abundantly

productive, as the quantity of sprats taken began to exceed the demand. At

one time sprats were selling as low as a 1s. per barrel.

The herring fishery of 1873 has been more than usually

productive, but no official statistics regarding it will be procurable

till next year. At some of the stations the curers were unable to operate

in consequence of an exhaustion of the materials of cure. Boats so seldom

reach an average of more than sixty crans that, in seasons when that

quantity is exceeded, the curer, counting on the average, is sure to be

found unprepared-hence large quantities of the fish are wasted, and a cry

is circulated of a prolific fishery, and men triumphantly point to the

fact, and ask What about "the fished-up" theory now? But the answer is not

far to seek : the number of boats and extent of netting ought to capture

double-nay treble-the quantity of herring they have taken this year, or

any previous year in which the take has been larger: Because the curers

have run out of the materials of cure the cry has arisen that we have had

a great fishery !

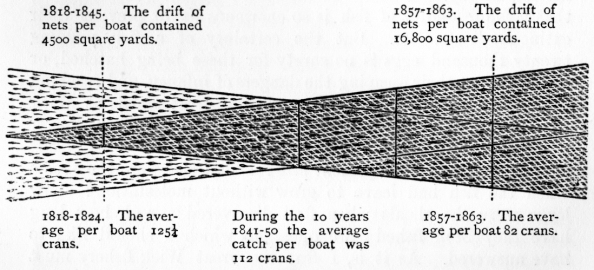

The quantity of netting now employed in the

herring-fishery is enormous, and is increasing from year to year. It has

been strongly represented by Mr. Cleghorn, and others who hold his

views, that the herring-fishery is on the decline ; that if the fish were

as plentiful as in former years, the increased amount of netting would

capture an increased number of herrings. It is certain that, with a

growing population and an increasing facility of transport, we are able to

use a far larger quantity of sea produce now than we could do fifty years

ago, when we were in the pre-Stephenson age. If, with our present

facilities for the transport of fish to inland towns, Great Britain had

been a Catholic instead of a Protestant country, having the example of the

French fisheries before us, I have no hesitation in saying that by this

time our fisheries would have been completely exhausted-that is, supposing

no remedial steps had been taken to guard against such a contingency. Were

we compelled to observe Lent with Catholic rigidity, and had there been

numerous fasts or fish-days, as there used to be in England before the

Reformation, the demand, judging from our present ratio, would have been

greater than the sea could have borne. Interested parties may sneer at

these opinions ; but, notwithstanding, I maintain that the pitcher is

going too often to the well, and that some day soon it will come back

empty.

I have always been slow to believe in the

inexhaustibility of the shoals, and can easily imagine the overfishing,

which some people pooh-pooh so glibly, to be quite possible, especially

when supplemented by the cod and other cannibals so constantly at work,

and so well described by the Lochfyne Commission; not that I believe it

possible to pick up or kill every fish of a shoal; but, as I have already

hinted, so many are taken, and the economy of the shoal so disturbed, that

in all probability it may change its ground or amalgamate with some other

herring colony. I shall be met here by the old argument, that "the

fecundity of fish is so enormous as to prevent their extinction," etc.

etc. But the certainty of a fish yielding twenty thousand eggs is no

surety for these being hatched, or if hatched, of their escaping the

dangers of infancy, and reaching the market as table food. I watch the

great shoals at Wick with much interest, and could wish to have been

longer acquainted with them. How long time have the Wick shoals taken to

grow to their present size? what size were the shoals when the fish had

leave to grow without molestation? - how large were the shoals when first

discovered - and how long have they been fished? are questions which I

should like to have answered. As it is, I fear the great Wick fishery must

come some day to an end. When the Wick fishery first began the fisherman

could carry in a creel on his back the nets he required ; now he requires

a cart and a good strong horse!

Although Scotland is the main seat of the herring

-fishery, I should like to see statistics, similar to those collected in

Scotland, taken at a few English ports for a period of years, in order

that we might obtain additional data from which to arrive at a right

conclusion as to the increase or decrease of the fishery for herring. It

is possible to collect statistics of the cereal and root crops of the

country ; it was done for all Scotland during three seasons, and it was

well and quickly accomplished. What can be done for the land may also, I

think, be done for the sea. I believe the present Board for Scotland to be

most useful in aiding the regulation of the fishery, and in collecting

statistics of the catch; their functions, however, might be considerably

extended, and elevated to a higher order of usefulness, especially as

regards the various questions in connection with the natural history of

the fish. The operations of the Board might likewise be extended for a few

seasons to a dozen of the largest English fishing-ports, in order that we

might obtain confirmation of what is so often rumoured, the falling off of

our supplies of sea-food. There are various obvious abuses also in

connection with the economy of our fisheries that ought to be remedied,

and which an active Board could remedy and keep right ; and a body of

naturalists and economists might easily be kept up at a slight toll of say

a guinea per boat.

The state of the case as between the supply of fish and

the extent of netting has been focussed into the annexed diagram, which

shows at a glance how the question stands.

|