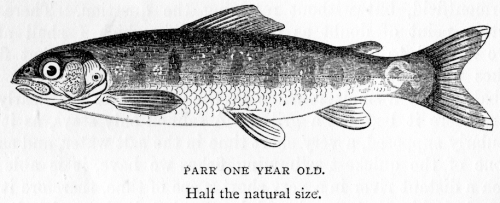

before that time it might be taken for anything else

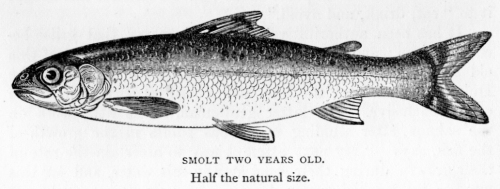

than a young salmon. Our engravings, which are exactly half the

size of life, show the progress of the salmon during

the first two years of its existence, at the end of which time it will,

most likely, have changed into a smolt. After eating up its umbilical bag,

which it takes a period of from twenty to forty days to accomplish, the

young salmon may be seen about its birthplace, timid and weak, hiding

among the stones, and always apparently of the same colour as the

surroundings of its sheltering place. The transverse bars of the parr very

early become apparent, and the fish begins to grow with considerable

rapidity, especially if it is to be a twelvemonths’ smolt, and this is

very speedily seen at such a good point of observation as the

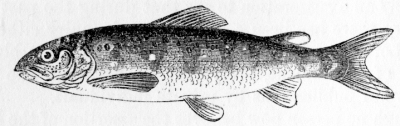

Stormontfield ponds. The smallest of the specimens given in the preceding

page represents a parr at the age of two months; the next in size shows

the same fish two months older; and the remaining fish is six months old.

The young fish continue to grow for a little longer than two years before

the whole number make the change from parr to smolt and seek the salt

water. Half of the quantity of any one hatching however, begin to change

at a little over twelve months from the date of their coming to life; and

thus there is the extra ordinary anomaly, as I shall by and by show, of

fish of the same hatching being at one and the same time parr of

half-an-ounce in weight and grilse weighing four pounds. The smolts of the

first year return from the sea whilst their brothers and sisters are

timidly disporting in the breeding shallows of the upper streams, having

no desire for change, and totally unable to endure the salt water, which

would at once kill them. The sea-feeding must be favourable, and the

condition of the fish well suited to the salt water, to ensure such rapid

growth—a rapidity which every visit of the fish to the ocean serves but to

confirm. Various fish, while in the grilse stage, have been marked to

prove this; and at every migration they returned to their breeding stream

with added weight and improved health. What the salmon feeds upon while in

the salt water is not well known, as the digestion of that fish is so

rapid as to prevent the discovery of food in their stomachs when

they are captured and opened. Guesses have been made, and it is likely

that these approximate to the truth; but the old story of the rapid voyage

of the salmon to the North Pole and back again turns out, like the theory

upon which was built up the herring-migration romance, to be a mere myth.

None of our naturalists have yet attempted to elucidate

that mystery of salmon life which converts one-half of the fish into

sea-going smolts, while as yet the other moiety remain as parr. It has

been investigated so far at the breeding-ponds at Stormontfield, but

without resolving the question. There is another point of doubt as to

salmon life which I shall also have a word to say about—namely, whether or

not that fish makes two visits annually to the sea; likewise whether it be

probable that a smolt remains in the salt water for nearly a year before

it becomes a grilse. A salmon only stays, as it is popularly supposed, a

very short time in the salt water, and as it is one of the quickest

swimming fishes we have, it is able to reach a distant river in a very

short space of time, therefore it is most desirable that we should know

what it does with itself when it is not migrating from one water to the

other; because, according to the opinion of some naturalists, it would

speedily become so deteriorated in the river as to be unequal to the

slightest exertion.

The mere facts in the biography of the salmon are not

very numerous; it is the fiction and mystery with which the life of this

particular fish have been invested by those ignorant of its history that

have made it a greater object of interest than it would otherwise have

become. This will be obvious as I briefly trace the amount of controversy

and state the arguments which have been expended on the three divisions of

its life.

The Parr Controversy. - None of the controversies

concerning the growth of the salmon have been so hotly carried on or have

proved so fertile in argument as the parr dispute. At certain seasons of

the year, most notably in the months of spring and early summer, our

salmon streams and their tributaries become crowded, as if by magic, with

a pretty little fish, known in Scotland as the parr, and in England as the

brandling, the peel, the samlet, etc. The parr was at one time so

wonderfully plentiful, that farmers and cottars who resided near a salmon

river used not unfrequently, after filling the family frying-pan, to feed

their pigs with the dainty little fish ! Countless thousands were annually

killed by juvenile anglers, and even so lately as thirty years ago it

never occurred either to country gentlemen or their cottars that these

parr were young salmon. Indeed, the young of the salmon, as then

recognised, was only known as a smolt or smout. Parr were thought, as I

have already said, to be distinct fish of the minor or dwarf kind. Some

large-headed anglers, however, had their doubts about the little parr, and

naturalists found it difficult to procure specimens

of the fish with ova or milt in them. Dr. Knox, the

anatomist, asserted that the parr was a hybrid belonging to no particular

species of fish, but a mixture of many; and it is curious enough that

although this fish was declared over and over again to be a separate

species, no one ever found a female parr containing roe. The universal

exclamation of naturalists for many a long year was always : It is a quite

distinct species, and not the young of any larger fish. The above drawing

represents a parr, the engraving being exactly half the size of life.

This "distinct-species "

dogma might have been still prevalent, had not the question been taken in

hand and solved by practical men. Before mentioning the experiments of

Shaw and Young, it will be curious to note the varieties of opinion which

were evoked during the parr controversy, which has existed in one shape or

another for something like two hundred years. As a proof of the difficulty

of arriving at a correct conclusion amidst the conflict of evidence, I may

cite the opinion of Yarrell, who held the parr to be a distinct fish.

" That the parr," he says, "is not the young or

the salmon, or, indeed, of any other of the large species of Salmonidae,

as still considered by some, is sufficiently obvious, from the

circumstance that parr by hundreds may be taken in the rivers all the

summer, long after the fry of the year of the larger migratory species

have gone down to the sea." Mr. Yarrell also says, "The smolt or young

salmon is by the fishermen of some rivers called ‘a laspring;’" and

explains, "The laspring of some rivers is the young of the true salmon;

but in others, as I know from having had specimens sent me, the laspring

is really only a parr." Mr. Yarrell further states the prevalence

of an opinion "that parrs were hybrids, and all of them males." Many

gentlemen who would not admit that parr were salmon in their first stage

have lived to change their opinion.

The first person who "took a thought about the matter"—

i.e., as to whether the parr was or was not the young of the

salmon—and arrived at a solid conclusion, was James Hogg, the Ettrick

Shepherd, who, in his usual impulsive way, proceeded to verify his

opinions. He had, while herding sheep, many opportunities of watching the

fishing-streams, and, like most of his class, he wielded his fishing-rod

with considerable dexterity. While angling in the tributaries of some of

the Border salmon-streams he had often caught the parr as it was changing

into the smolt, and had, after close observation, come to the conclusion

that the little parr was none other than the infant salmon. Mr. Hogg did

not keep his discovery a secret, and the more his facts were controverted

by the naturalists of the day the louder became his proclamations. He had

suspected all his life that parr were salmon in their first stage. He

would catch a parr with a few straggling scales upon it; he would look at

this fish and think it queer; instantly he would catch another a little

better covered with silver scales, but all loose, and not adhering to the

body. Again he would catch a smolt, manifestly a smolt, all covered with

the white silver scales, yet still rather loose upon its skin, which would

come off in his hand. Removing these scales he found the parr, with the

blue finger-marks below them, and that the fish were young salmon then

became as manifest to the Shepherd as that a lamb, if suffered to live,

would become a sheep. Wondering at this, he marked a great number of the

lesser fish, and offered rewards (characteristically enough of whisky) to

the peasantry to bring him such as had evidently undergone the change

predicted by him. Whenever this conclusion was settled in his mind, the

Shepherd at once proclaimed his new-gained knowledge. "What will the

fishermen of Scotland think," said he, "when I assure them, on the faith

of long experience and observation, and on the word of one who can have no

interest in instilling an untruth into their minds, that every

insignificant parr with which the Cockney fisher fills his basket is a

salmon lost." These crude attempts of the impulsive shepherd of Ettrick -

and he was hotly opposed by the late Mr. Burst of Stormontfield - were not

without their fruits; indeed they were so successful as quite to convince

him that parr were young salmon in their first stage.

As I have had occasion to mention the opinions of James

Hogg on the salmon question, I may be allowed to state here that the

following amusing bit of dialogue on the habits of the salmon once took

place between the Ettrick Shepherd and a friend:

Shepherd - "I maintain that ilka saumon comes

aye back again frae the sea till spawn in its ain water."

Friend - "Toots, toots, Jamie ! hoo can it manage

till do that ? hoo, in the name o' wonder, can a fish, travelling up a

turbid water frae the sea, know when it reaches the entrance to its

birthplace, or that it has arrived at the tribituary that was its cradle!"

Shepherd - "Man, the great wonder to me is no hoo

the fish get back, but hoo they find their way till the sea first ava,

seein' that they've never been there afore !"

The parr question, however, was determined in a rather

more formal mode than that adopted by the author of "Bonny Kilmenny." The

late Mr. Shaw, a forester in the employment of the Duke of Buccleuch, took

up the case of the parr in 1833, and succeeded in solving the problem. In

order that he might watch the progressive growth of the parr, Mr. Shaw

began by capturing seven of these little fishes on the 11th of July 1833 ;

these he placed in a pond supplied by a stream of excellent water, where

they grew and flourished apace till early in April 183-1, between which

date and the 17th of the following May they became smolts ; and all who

saw them on that day when they were caught by Mr. Shaw were thoroughly

convinced that they were true salmon smolts. In March 1835 Mr. Shaw

repeated his experiments with twelve parrs of a larger size, taken also

from the river. On being transferred to the pond, these so speedily

acquired the scales of the smolt that Mr. Shaw assumed a period of two

years as being the time at which the change took place from the parr to

the smolt. The late Mr. Young of Invershin, a well-known authority on

salmon life, was experimenting at the same time as Mr. Shaw, and for the

same purpose-namely, to determine if parr were young salmon, and, if so,

at what period they became smolts and proceeded to the sea. Mr. Shaw said

two years, and Mr. Young, who was then manager of the Duke of Sutherland's

fisheries, said the change took place in twelve months; others, again, who

took an interest in the controversy, said that three years elapsed before

the change was made. The various parties interested held each their own

opinion, and it may even be said that the disputation still goes on; for

although a numerous array of facts bearing on the migration have been

gathered, we are still in ignorance of any regulating principle on which

the migratory change is based, or to account for the impulse which impels

a brood of fish to proceed to sea divided into two moieties. Mr. Shaw

watched his young fry with unceasing care, and described their growth with

great minuteness, for a period extending over two years, when his parrs

became smolts. Mr. Young, in a letter from Invershin, dated January 1853,

says, pointedly enough - "The fry remain in the river one whole year, from

the time they are hatched to the time they assume their silvery coat and

take their first departure for the sea. All the experiments we have made

on the ova and fry of the salmon have exactly corresponded to the same

effects, and none of them have taken longer in arriving at the smolt than

the first year."

The late Mr. Burst, in one of his letters on the

progress of artificial breeding at the Stormontfield ponds, says: "There

is at present a mystery as regards the progress of the young salmon. There

can be no doubt that all in our ponds are really and truly the offspring

of salmon; no other fish, not even the seed of them, could by any

possibility get into the ponds. Now we see that about one half have gone

off as smolts, returning in their season as grilses; the other half remain

as parrs, and the milt in the males is as much developed, in proportion to

the size of the fish, as their brethren of the same age seven to ten

pounds weight, whilst these same parrs in the ponds do not exceed one

ounce in weight. This is an anomaly in nature which I fear cannot be

cleared up at present. I hope, however, by proper attention, some light

may be thrown upon it from our experiments next spring. The female parrs

in the pond have their ova so undeveloped that the granulations can

scarcely be discovered by a lens of some power. It is strange that both

Young's and Shaw's theories are likely to prove correct, though seemingly

so contradictory, and the much-disputed point settled, that parrs (such as

ours at least) are truly the young of the salmon."

It is quite certain that parr are young salmon, and

that a parr becomes a smolt and goes to the sea, although there are still

to be found, no doubt, a few wrong-headed people who refuse to be

convinced on the point, but pridefully maintain all the old salmon

theories and prejudices. With them the parr is still a distinct fish, the

smolt is the true young of Salmo salar in its first stage, and a

grilse is just a grilse and nothing more. However, these old-world people

will in time pass away (there is no hope of converting them), and then the

modern views of salmon biography, founded as they are on laborious

personal investigation, will ultimately prevail.

The Smolt and Grilse. - But the great parr mystery is

still unsolved-that is to say, no one knows on what principle the

transformation is accomplished ; why it is that only half of a brood ripen

into smolts at the end of a year, the other moiety taking double that

period to arrive at the same stage of progress. Some scientific visitors

to the Stormontfield ponds say that this anomaly is natural enough, and

that similar ratios of growth may be observed among all animals ; but it

is curious that just exactly the half of a brood-and the eggs, be it

remembered, all from adult salmon, and therefore similar in ripeness and

other conditions-should change into smolts at 'the end of a year, leaving

a moiety in the ponds as parr for another twelvemonth.

The most remarkable phase in the life of the salmon is

its extraordinary instinct for change. After the parr has become a smolt,

it is found that the desire to visit the sea is so intense, especially in

pond-bred fish, as to cause them to leap from their place of confinement,

in the hope of attaining at once their salt-water goal ; and of course the

instinct of river-bred fish is equally strong on this point-they all rush

to the sea at their proper season. There are various opinions as to the

cause of this migratory instinct in the salmon. Some people say it finds

in the sea those rich feeding-grounds which enable it to add so rapidly to

its weight. It is quite certain that the fish attains its primest

condition while it is in the salt water; those caught in the estuaries by

means of stake or bag nets being richer in quality and finer in flavour

than the river fish : the moment the salmon enters the fresh water it

begins to decrease in weight and fall from its high condition. It is a

curious fact, and a wise provision of nature, that the eel, which is also

a migratory fish, descends to spawn in the sea as the salmon is ascending

to the river-head for the same purpose ; were the fact different, and both

fish to spawn in the river, the roe of the salmon would be completely

eaten up. In due time then, we find the silver-coated host leaving the

rippling cradle of its birth, and adventuring on the more powerful stream,

by which it is borne to the sea-fed estuary, or the briny ocean itself.

And this picturesque tour is repeated year after year, being apparently

the grand essential of salmon life.

It is pleasant, rod in hand, on a breezy spring day,

while trying to coax " the monarch of the brook " from his sheltering

pool, to watch this annual migration, and to note the passage of the

bright-mailed army adown the majestic river, that hurries on by busy

corn-mill, and sweeps with a murmuring sound past hoar and ruined towers,

washing the pleasant lawns of country magnates or laving the cowslips on

the

village meadow, and as it rolls ceaselessly ocean-ward,

giving a more picturesque aspect to the quaint agricultural villages and

farm homesteads which it passes in its course. During the whole length of

its pilgrimage the army of smolts pays a tribute to its enemies in gradual

decimation : it is attacked at every point of vantage ; at one place the

smolts are taken prisoners by the hundred in some well-contrived net, at

another picked off singly by some juvenile angler. The smolt is greedily

devoured by the trout, the pike, and various other enemies, which lie

constantly in waiting for it, sure of a rich feast at this

annually-recurring migration. But the giant and fierce battle which this

infantile tribe has to fight is at the point where the salt water begins

to mingle with the stream, where are assembled hosts of greedy monsters of

the deep of all shapes and sizes, from the porpoise and seal down to the

young coal-fish, who dart with inconceivable rapidity upon the defenceless

shoal, and play havoc with the numbers.

Many naturalists dispute most lustily the assertion

that the smolt returns to the parental waters as a grilse the same year

that it visits the sea ; and some writers have maintained that the young

fish makes a grand tour to the North Pole before it makes up its mind to "

hark back." It has been pretty well proved, however, that the grilse may

have been the young smolt of the same year. A most remarkable fact in the

history of grilse is, that we kill them in thousands before they have an

opportunity of perpetuating their kind ; indeed on some rivers the annual

slaughter of grilse is so enormous as palpably to affect the " takes " of

the big fish. It has been asserted, likewise, that the grilse is a

distinct fish, and not the young of the salmon in its early stage.' There

has been a controversy as to the rate at which the salmon increases in

weight ; and there have been numerous disputes about what its instinct had

taught it to " eat, drink, and avoid."

It has been authoritatively settled, however, that

grilse become salmon ; and, notwithstanding a recent opening up of this

old sore, I hold the experiments conducted by his Grace the Duke of Athole

and the late Mr. Young of Invershin to be quite conclusive. The latter

gentleman, in his little work on the salmon, after alluding to various

points in the growth of the fish, says-" My next attempt was to ascertain

the rate of their growth during their short stay in salt water, and for

this purpose we marked spawned grilses, as near as we could get to four

pounds weight ; these we had no trouble in getting with a net in the pools

below the spawning-beds, where they had congregated together to rest,

after the fatigues of depositing their seed. All the fish above four

pounds weight, as well as any under that size, were returned to the river

unmarked, and the others marked by inserting copper wire rings into

certain parts of their fins : this was done in a manner so as not to

interrupt the fish in their swimming operations, nor be troublesome to

them in any way. After their journey to sea and back again, we found that

the four-pound grilses had grown into beautiful salmon, varying from nine

to fourteen pounds weight. I repeated this experiment for several years,

and on the whole found the results the same, and, as in the former

marking, found the majority returning in about eight weeks; and we have

never among our markings found a marked grilse go to sea and return a

grilse, for they have invariably returned salmon."

The late Duke of Athole took considerable interest in

the grilse question, and kept a complete record of all the fish that he

had caused to be marked ; and in his Journal there is a striking instance

of rapidity of growth. A fish marked by his Grace was caught at a place

forty miles distant from the sea; it travelled to the salt water, fed, and

returned in the short space of thirty-seven days. The following is his

entry regarding this particular fish:- "On referring to my Journal, I find

that I caught this fish as a kelt this year, on the 31st of March, with

the rod, about two miles above Dunkeld Bridge, at which time it weighed

exactly ten pounds; so that, in the short space of five weeks and two

days, it had gained the almost incredible increase of eleven pounds and a

quarter ; for, when weighed here on its arrival, it was twenty-one pounds

and a quarter." There could be no doubt, Mr. Young thinks, of the accuracy

of this statement, for his Grace was most correct in his observations,

having tickets made for the purpose, and numbered from one upwards, and

the number and date appertaining to each fish was carefully registered for

reference.

As the fish grew so rapidly during their visit to the

salt water, people began to wonder what they fed on, and where they went.

A hypothesis was started of their visiting the North Pole ; but it was

certain, from the short duration of their visit to the salt water that

they could proceed to no great distance from the mouth of the river which

admitted them to the sea. Hundreds of fish were dissected in order to

ascertain what they fed upon ; but only on very rare occasions could any

traces of food be found in their stomachs. What, then, do salmon live

upon? was asked. It is quite clear that salmon obtain in the sea some kind

of food for which they have a peculiar liking, and upon which they rapidly

grow fat; and it is very well known that after they return to the fresh

water they begin to lose flesh and fall off in condition. The rapid growth

of the fish seems to imply that its digestion must be rapid, and may

perhaps account for food never being in its stomach when found; although I

am bound to mention that one gentleman who writes on this subject accounts

for the emptiness of the stomach by asserting that salmon vomit at the

moment of being taken. The codfish again is frequently found with its

stomach crowded; in fact, I have seen the stomach of a large cod which

formed quite a small museum, having a large variety of articles "on

board," as the fisherman said who caught it.

It is supposed by some writers that salmon make two

voyages in each year to the sea, and this is quite possible, as we may

judge from data already given on this point; but sometimes the salmon,

although it can swim with great rapidity, takes many weeks to accomplish

its journey, because of the state of the river. If there be not sufficient

water to flood the course, the fish must remain in various pools till the

state of the water admits of their proceeding on their journey either to

or from the sea. The salmon, like all other fish, is faithful to its old

haunts; and it is known, in cases where more than one salmon-stream falls

into the same firth, that the fish of one stream will not enter another,

and where the stream has various tributaries suitable for breeding

purposes, the fish breeding in a particular tributary invariably return to

it.

But, in reference to the idea of a double visit to the

salt water, may we not ask-particularly as we have the dates of marked

fish for our guidance-what a salmon that is known to be only five weeks

away on its sea visit does with itself the rest of the year ? A salmon,

for instance, spawning about "the den of Airlie," on the Isla, some way

beyond Perth, has not to make a very long journey before it reaches the

salt water, and travelling at a rapid rate would soon accomplish it; but

supposing the fish took thirty days for its passage there and back, and

allowing a period of four weeks for spawning and rest, there are still

many months of its annual life unaccounted for. It cannot remain in the

river forty-seven weeks, because it would become so low in condition from

the want of a proper supply of nourishing food that it would die; and it

is this fact that has led to the supposition of a double journey to the

sea. The Rev. Dugald Williamson, who wrote a pamphlet on this subject,

entertains no doubt about the double journey. "Salmon migrate twice in the

course of the year, and the instinct which drives them from the sea in

summer impels them to the sea in spring. Let the vernal direction of the

propensity be opposed, let a salmon be seized as it descends and confined

in a fresh-water pond or lake, and what is its fate? Before preparing to

quit the river it had suffered severely in strength, bulk, and general

health, and, imprisoned in an atmosphere which had become unwholesome, it

soon begins to languish, and in the course of the season expires : the

experiment has been tried, and the result is well known. This being an

ascertained and unquestionable fact, is it a violent or unfair inference

that a similar result obtains in the case of those salmon that are forced

back, from whatever cause, to the sea, that the salt-water element is as

fatal to the pregnant fish of autumn as the fresh-water element is to the

spent fish in spring? . . . If there is any truth in these conjectures,

they suggest the most powerful reasons for resisting or removing

obstructions in the estuary of a river." The riddle of this double

migration of the salmon is likely still to puzzle us. It is said that the

impelling force of the migratory instinct is, that the fish is preyed upon

in the salt water by a species of crustaceous insect, which forces it to

seek the fresh waters of its native river; again that while the fresh

water destroys these sea-lice a parasite infests it in the river, thus

necessitating its return to the sea. My own experience leads me to believe

that salmon can exist in the fresh water for a considerable time, and

suffer but little deterioration in weight, but they never, so far as I

could ascertain, grow while in the fresh streams. It is a well-known fact

that parr cannot live in salt water. I have both tried the experiment

myself and seen it tried by others; the parr invariably die when placed in

contact with the sea-water.

Mr. William Brown, in his painstaking account of The

Natural History of the Salmon, also bears his testimony on this part

of the salmon question:- "Until the parr takes on the smolt scales, it

shows no inclination to leave the fresh water. It cannot live in salt

water. This fact was put to the test at the ponds, by placing some parrs

in salt water-the water being brought fresh from the sea at Carnoustie;

and immediately on being immersed in it the fish appeared distressed, the

fins standing stiff out, the parr-marks becoming a brilliant ultramarine

colour, and the belly and sides of a bright orange. The water was often

renewed, but they all died, the last that died living nearly five hours.

After being an hour in the salt water, they appeared very weak and unable

to rise from the bottom of the vessel which contained them, the body of

the fish swelling to a considerable extent. This change of colour in the

fish could not be attributed to the colour of the vessel which held them,

for on being taken out they still retained the same brilliant colours."

All controversies relating to the growth of salmon may

now be held as settled. It has been proved that the parr is the young of

the salmon; the various changes which it undergoes during its growth have

been ascertained, and the increase of bulk and weight which accrues in a

given period is now well understood. But we still require much information

as to the "habits" of fish of the salmon kind.

In a recent conversation with Air Marshall of

Stormontfield, while comparing notes on some of the disputed points of

salmon growth, we both came to the conclusion that the following dates,

founded on the experiments conducted at Stormontfield, might be taken as

marking the chief stages in the life of a salmon. An egg deposited in the

breeding-boxes in December 1869 yielded a fish in April 1870 ; that fish

remained as a parr till a little later than the same period of 1871, when,

being seized with its migratory instinct, and having upon it the

protecting scales of the smolt, it departed from the pond into the river

Tay on its way to the sea, having previously had conferred upon it a

certain mark by which it could be known if recaptured on its return. It

was recaptured as a grilse within less than three months of its departure

(July), and weighed about four pounds. Being marked once more, it was

again sent away to endure the dangers of the deep; and lo I was once more

taken, this time a salmon of the goodly weight of ten pounds ! But there

comes in here the question if it was the same fish, for it is said that

the smolt in some cases remains a whole winter in the sea, and therefore

that the fish I have been alluding to was a smolt that had never come back

as a grilse. I have a theory that half of the brood of smolts sent to sea

do remain over the winter and come back as salmon, while the others come

back almost immediately as grilse. It is possible, however, that any

particular fish may lose its river for a season, and be in some other

water for a time as a grilse, and then finding its birth-stream come once

again to its " procreant cradle." The rapidity of salmongrowth, however, I

consider to be undoubtedly proved.

A good deal has been said in various quarters about the

best way of marking a young salmon, so that at some future stage of its

life it may be easily identified. Cutting off the dead fin is not thought

a good plan of marking, because such a mark may be accidentally imitated,

and so mislead those interested, or it may be wilfully imitated by persons

wishing to mislead. Of the smolts sent away from the Stormontfield ponds

during May 1855, 1300 were marked in a rather common way - viz. by cutting

off the second dorsal fin-and twenty-two of these marked fish were taken

as grilse during that same summer, the first being caught on the 7th of

July, when it weighed three pounds. The late Mr. Buist, who took charge of

the experiments, was quite convinced that a much larger number of the

marked fish than twenty-two was caught, but many of the fishermen, having

an aversion to the system of pond-breeding, took no pains to discover

whether or not the grilse they caught had the pond-mark, and so the chance

of still further verifying the rate of salmon growth was lost. A reward

offered by Mr. Buist of 2s. per pound weight for each grilse that might be

brought to his office, led to an imitation of the mark and the

perpetration of several petty frauds in order to get the money. The mark

was frequently imitated, and one or two fish were brought to Mr. Buist

which almost deceived him into the belief of their being some of the real

marked fish. As Mr. Buist said - " So cunningly had this deception been

gone about, that a casual observer might have been deceived. When the fin

was cut off the recent wound was far too palpable ; and to hide this the

man cut a piece of skin from another fish and fixed it upon the wounded

part. I examined this fish, which was lying alongside of an undoubted

pond-marked fish, which had the skin and scales grown over the cut, and I

am satisfied that it would be impossible to imitate the true mark by any

process except by marking the fish while young." [In a very old number of

the Scots Magazine I find the following :" I was told by a

gentleman who was present at a boat's fishing on Spey near Gordon Castle

in the month of April, that in hauling, the weight of the net brought out

a great number of smouts which the fishers were not willing to part with ;

but that a gentleman, who knew the natural propensity of the salmon to

return to their native river, persuaded them to slip them back again into

the water, assuring them that in two months they would catch most of them

full-grown grilses, which would be of much greater value. He at the same

time laid a bet of five guineas with another gentleman present, who was

somewhat dubious, that he should not fail in his prediction. The fishers

agreed. He accordingly clipt off a part of the tail-fins from a number of

them before he dropped them into the river ; and within the time limited

the fishers actually caught upwards of a hundred grilses thus marked, and

soon after many more." ] Peter Marshall, the intelligent keeper of the

ponds, agrees with me in saying that the number of fish taken, each being

minus the dead fin, was a sufficient proof that these fish were really the

pond-bred ones returned as grilse. It is impossible that twenty or thirty

grilse could have all been accidentally maimed within a few weeks, and

each present the same—the very same appearance. Various other plans of

marking were tried by the authorities at Stormontfield, some of which were

partially successful, and added another link to the chain of evidence,

which proves at any rate that many individual fish have grown from the

smolt to the grilse state in the course of a very few weeks.