|

Almost the only fuel used

by the Highlanders, not only in the early part but during the whole of

last century, was peat, still used in many Highland districts, and the

only fuel used in a great part of Orkney and Shetland. The cutting and

preparing of the fuel, composed mainly of decayed roots of various plants,

consumed a serious part of the Highlander’s time, as it was often to be

found only at a great distance from his habitation; and he had to cut not

only for himself but for his land, the process itself being long and

troublesome, extending from the time the sods were first cut till they

were formed in a stack at the side of the farmer’s or cottar’s door,

over five or six months; and after all, they frequently turned out but a

wretched substitute for either wood or coal; often they were little else

than a mass of red earth. It generally took five people to cut peats out

of one spot. One cut the peats, which were placed by another on the edge

of the trench from which they were cut; a third spread them on the field,

while a fourth trimmed them, a fifth resting in the meantime ready to

relieve the man that was cutting.

As would naturally be

expected, the houses and other buildings of the Highlanders were quite in

keeping with their agricultural implements and general mode of life. Even

the tacksmen or gentlemen of the clan, the relations of the chief, lived

in huts or hovels, that the poorest farmer in most parts of Scotland at

the present day, would shudder to house his cattle in. In most cases they

appear to have been pretty much the same as those of the small farmers or

cottars, only perhaps a little larger. Burt mentions such a house

belonging to a gentleman of the clan, which he visited in one of his

peregrinations round Inverness. He says it consisted of one long apartment

without any partition, "where the family was at one end, and some

cattle at the other." The owner of this rude habitation must have

been somewhat shrewd and sensible, as he could not only perceive the

disadvantages of this mode of life to which he was doomed, but had insight

and candour enough to be able to account for his submission to them.

"The truth is," Captain Burt reports him to have said, "we

are insensibly inured to it by degrees; for, when very young, we know no

better; being grown up, we are inclined, or persuaded by our near

relations, to marry—thence come children, and fondness for them but

above all," says he, "is the love of our chief, so

strongly is it inculcated to us in our infancy; and if it were not for

that, I think the Highlands would be much thinner of people than they now

are." How much truth there is in that last statement is clearly

evidenced by the history of the country after the abolition of the

hereditary jurisdictions, which was the means of breaking up the old

intimate relation between, and mutual dependence of, chief and people.

Burt says elsewhere, that near to Inverness, there were a few gentlemen’s

houses built of stone and lime, but that in the inner part of the

mountains there were no stone-buildings except the barracks, and that one

might have gone a hundred miles without seeing any other dwellings but

huts of turf. By the beginning of last century the houses of most of the

chiefs, though comparatively small, seem to have been substantially built

of stone and lime, although their food and manner of life would seem to

have been pretty much the same as those of the tacksmen. The children of

chiefs and gentlemen seem to have been allowed to run about in much the

same apparently uncared for condition as those of the tenants, it having

been a common saying, according to Burt, "that a gentleman’s bairns

are to be distinguished by their speaking English." To illustrate

this he tells us that once when dining with a laird not very far from

Inverness—possibly Lord Lovat—he met an English soldier at the house

who was catching birds for the laird to exercise his hawks on. This

soldier told Burt that for three or four days after his first coming, he

had observed In the kitchen ("an out-house hovel") a parcel of

dirty children half naked, whom he took to belong to some poor tenant, but

at last discovered they were part of the family. "But," says the

fastidious English Captain, "although these were so little regarded,

the young laird, about the age of fourteen, was going to the university;

and the eldest daughter, about sixteen, sat with us at table, clean and

genteelly dressed."

There is no reason to doubt

Burt’s statement when he speaks of what he saw or heard, but it must be

remembered he was an Englishman, with all an Englishman’s prejudices in

favour of the manners and customs, the good living, and general

fastidiousness which characterise his own half of the kingdom, and many of

an Englishman’s prejudices against the Scotch generally and the

turbulent Highlanders in particular. His letters are, however, of the

utmost value in giving us a clear and interesting glimpse into the mode of

life of the Highlanders shortly before 1745, and most Scotchmen at least

will be able to sift what is fact from what is exaggeration and English

colouring. Much, no doubt, of what Burt tells of the Highlanders when he

was there is true, but it is true also of people then living in the same

station in other parts of Scotland, where however among the better

classes, and even among the farmers, even then, there was generally a

rough abundance combined with a sort of affectation of rudeness of manner.

It is not so very long ago since the son of the laird, and he might have

been a duke, and the son of the hind were educated at the same parish

school; and even at the present day it is no uncommon sight to see the

sons of the highest Scottish nobility sitting side by side on the same

college-benches with the sons of day labourers, ploughmen, mechanics,

farmers, and small shop-keepers. Such a sight is rare in the English

universities; where there are low-born intruders, it will in most cases be

found that they belong to Scotland. We do not make these remarks to

prejudice the reader in any way against the statements of Burt or to

depreciate the value of his letters; all we wish the reader to understand

is that he was an Englishman, rather fond of gossip, and perhaps of adding

point to a story at the expense of truth, with all the prejudices and want

of enlightenment and cosmopolitanism of even educated Englishmen of 150

years ago. He states facts correctly, but from a peculiar and very

un-Scottish point of view. His evidence, even when stripped of its slight

colouring, is invaluable, and, even to the modern Highlander, must prove

that his ancestors lived in a very miserable way, although they themselves

might not have realised its discomfort and wretchedness, but on the

contrary, may have been as contented as the most well-to-do English squire

or prosperous English farmer.

Even among the higher

members of the clans, the tacksmen and most extensive farmers, the fare

does not seem to have been by any means abundant, and generally was of the

commonest kind. For a few months in the end of the year, when the cattle

and sheep were in condition to be killed, animal food appears to have been

plentiful enough, as it must also have been after any successful

cattle-foray. But for the rest of the year, the food of even the gentlemen

in many places must have been such as any modern farmer would have turned

up his nose at. In other districts again, where the chief was well-off and

liberal, he appears to have been willing enough to share what he had with

his relations the higher tenants, who again would do their best to keep

from want the under tenants and cottars. Still it will be seen, the living

of all was very precarious. "it is impossible for me," says

Burt, "from my own knowledge, to give you an account of the ordinary

way of living of these gentlemen; because, when any of us (the English)

are invited to their houses there is always an appearance of plenty to

excess; and it has been often said they will ransack all their tenants

rather than we should think meanly of their housekeeping: but I have heard

it from many whom they have employed, and perhaps had little regard to

their observations as inferior people, that, although they have been

attended at dinner by five or six servants, yet, with all that state, they

have often dined upon oatmeal varied several ways, pickled herrings, or

other such cheap and indifferent diet." Burt complains much of their

want of hospitality; but at this he need not have been surprised. He and

every other soldier stationed in the Highlands would be regarded with

suspicion and even dislike by the natives, who were by no means likely to

give them any encouragement to frequent their houses, and pry into their

secrets and mode of life. The Highlanders were well-known for their

hospitality, and are so in many places even at the present day, resembling

in this respect most people living in a wild and not much frequented

country. As to the everyday fare above mentioned, those who partook of it

would consider it no hardship, if indeed Burt had not been mistaken or

been deceived as to details. Oatmeal, in the form of porridge and brose,

is common even at the present day among the lower classes in the country,

and even among substantial farmers. As for the other part of it, there

must have been plenty of salmon and trout about the rivers and lochs of

Inverness-shire, and abundance of grain of various kinds on the hills, so

that the gentlemen to whom the inquisitive Captain refers, must have taken

to porridge and pickled herring from choice: and it is well known, that in

Scotland at least, when a guest is expected, the host endeavours to

provide something better than common for his entertainment. Burt also

declares that he has often seen a laird’s lady coming to church with a

maid behind her carrying her shoes and stockings, which she put on at a

little distance from the church. Indeed, from what he says, it would seem

to have been quite common for those in the position of ladies and

gentlemen to go about in this free and easy fashion. Their motives for

doing so were no doubt those of economy and comfort— not because they

had neither shoes nor stockings to put on. The practice is quite common at

the present day in Scotland, for both respectable men and women when

travelling on a dusty road on a broiling summer-day, to do so on their

bare feet, as being so much more comfortable and less tiresome than

travelling in heavy boots and thick worsted stockings. No one thinks the

worse of them for it, nor infers that they must be wretchedly ill off. The

practice has evidently at one time been much more common even among the

higher classes, but, like many other customs, lingers now only among the

common people.

From all we can learn,

however, the chiefs and their more immediate dependants and relations

appear by no means to have been ill-off, so far as the necessaries of life

went, previous to the rebellion of 1745. They certainly had not a

superfluity of money, but many of the chiefs were profuse in their

hospitality, and had always abundance if not variety to eat and drink.

Indeed it is well known,

that about 200 years before the rebellion, an enactment had to be made by

parliament limiting the amount of wine and brandy to be used by the

various chiefs. Claret, in Captain IBurt’s time, was as common m and

around Inverness as it was in Edinburgh; the English soldiers are said to

have found it selling at sixpence a quart, and left it at three or four

times that price. In their habits and mode of life, their houses and other

surroundings, these Highland gentlemen were no doubt rough and rude and

devoid of luxuries, and not over particular as to cleanliness either of

body or untensils, but still always dignified and courteous, respectful to

their superiors and affable to their inferiors. Highland pride is still

proverbial, and while often very amusing and even pitiable, has often been

of considerable service to those who possess it, stimulating them to keep

up their self-respect and to do their best in whatever situation they may

be placed. It was this pride that made the poorest and most tattered of

the tacksmen tenants with whom Burt came in contact, conduct himself as if

he had been lord of all he surveyed, and look with suspicion and perhaps

with contempt upon the unknown English red-coat.

As a kind of set-off to

Burt’s disparaging account of the condition of Highland gentlemen, and

yet to some extent corroborating it, we quote the following from the Old

Statistical Account of the parish of Boleskine and Abertarf in

Inverness-shire. The district to which this account refers was at least no

worse than most other Highland parishes, and in some respects must have

been better than those that were further out of the reach of civilisation.

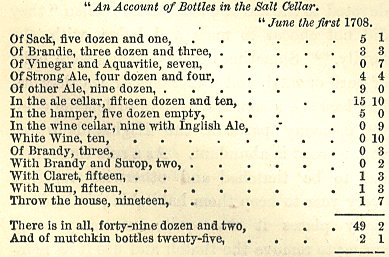

The following quotations

from Mr Dunbar’s Social Life in

Former Days, giving details of

household furniture and expenses, may be taken as "a correct index of

the comforts and conveniences" of the best off of the old Highland

lairds; for as they refer to Morayshire, just on the borders of the

Highlands, they cannot be held as referring to the Highlands generally,

the interior and western districts of which were considerably behind the

border lands in many respects:-

INVENTAR OF PLENISHING IN

THUNDERTON’S LODGING IN DUFFUS, MAY 25, 1708.

Strypt Room.

"Camlet hangings and

curtains, feather bed and bolster, two pillows, five pair blankets, and an

Inglish blanket, a green and white cover, a blew and white chamber-pot, a

blew and white bason, a black jopand table and two looking-glasses, a

jopand tee-table with a tee-pat and plate, and nine cups and nine dyshes,

and a tee silver spoon, two glass sconces, two little bowles, with a leam

steep and a pewter head, eight black ken chairs, with eight silk cushens

conform, an easie chair with a big cushen, a jopand cabinet with a walnut

tree stand, a grate, shuffle, tonges, and brush; in the closet, three

piece of paper hangings, a chamber box. with a pewter pan therein, and a

brush for cloaths.

Closet next

the Strypt Room.

Four dishes, two assiets,

six broth plates, and twelve flesh plates, a quart flagon, and a pynt

flagon, a pewter porenger, and a pewter flacket, a white iron jaculale

pot, and a skellet pann, twenty-one timber plates, a winter for warming

plates at the fire, two Highland plaids, and a sewed blanket, a bolster,

and four pillows, a chamber-box, a sack with wool, and a white iron

dripping pann.

In the farest Closet.

"Seventeen drinking

glasses, with a glass tumbler end two decanters, a oil cruet, and a

vinegar cruet, a urinal glass, a large blew and white posset pot, a white

leam posset pat, a blew and white bowl, a dozen of blew and white leam

plates, three milk dishes, a blew and white leam porenger, and a white

leam porenger, four jelly pots, and a little butter dish, a crying chair,

and a silk craddle.

In the Moyhair Room.

"A note of stamped

cloath hangings, and a moyhair bed with feather bed, bolster, and two

pillows, six pair blankets, and an lnglish blanket and a twilt, a leam

chamber-pat, five moyhalr chairs, two looking-glasses, a cabinet, a table,

two stands, a table cloak, and window hangings, a chamber-box with a

pewter pann, a leam bason, with a grate and tongs and a brush; in the

closet, two carpets, a piece of Arres, three pieces lyn’d strypt

hangings, three wawed strypt curtains, two piece gilded leather, three

trunks and a craddle, a chamber-box, and a pewter pann, thirty-three pound

of heckled lint, a ston of vax, and a firkin of sop, and a brush for

cloaths, two pair blankets, and a single blanket.

In lhe Dyning-Room.

"A sute of gilded

hangings, two folding tables, eighteen low-backed ken chairs, a grate, a

fender, a brass tongs, shuffle, brush, and timber brush, and a poring

iron, and a glass ken.

In my Lady’s Room.

"Gilded hangings,

standing bed, and box bed, stamped drogged hangings, feather bed, bolster,

and two pillows, a pallise, five pair of blankets, and a single one, and a

twilt, and two pewter chamber-pots, six chairs, table, and looking-glass a

little folding table, and a chist of drawers, tonges, shuffle, porrin-iron

and a brush, two window curtains of linen; In the Laird's closet, two

trunks, two chists, and a citrena cabinet, a table, and a looking-glass,

the dow holes, two carpet chairs, and a chamber-box with a pewter pan, and

a little bell, and a brush tar cloath.

My Lady’s Closet.

"A cabinet, three

presses, three kists, and a spicerie box, a dozen leam white plates, a

blew and white leam plate, a little blew butter plate, a white leam

porenger, and three gelly pots, two leam dishes, and two big timber capes,

four tin congs, a new pewter basson, a pynt chopen, and matchken stoups,

two copper tankers, two pewter salts, a pewter mustard box, a white iron

paper and suggar box, two white iron graters, a pot for starch, and a

pewter spoon, thirteen candlesticks, five pair snuffers and snif dishes

conform, a brass mortar and pistol, a lantern, a timber box, a dozen

knives and a dozen forks, and a carpet chair, two milk conga, a milk cirn,

and kirn staff, a sisymilk, and a cheswel, a neprie basket, and two new

pewter chamber pots.

A Note of Plate.

"Three silver salvers,

four salts, a large tanker, a big spoon, and thirteen littler spoons, two

jugs, a sugar box, a mustard box, a paper box, and two little spoons.

"Received ten dozen and one of chapen

bottles full of claret. More received—eleven dozen and one of pynt

bottles, wbereof there was six broke in the home-coming. 1709, June the

4th, received from Elgin forty-three chopen bottles of claret."

"Till the beginning of

this century, all the heritors and wadsetters in this parish lived in

houses composed of cupple trees, and the walls and thatch made up of sod

and divot; but in every wadsetter’s house there was a spacious hall,

containing a largetable, where he and his family and dependants eat their

two meals a-day with this single distinction, that he and his family sat

at the one end of the table, and his dependants at the other; and it was

reckoned no disparagement for the gentlemen to sit with commoners in the

inns, such as the country then afforded, where one cap, and

afterwards a single glass, went round the whole company. As the

inhabitants experienced no want, and generally lived on the produce of

their farms, they were hospitable to strangers, providing they did not

attempt a settlement among them. But it was thought then disgraceful for

any of the younger sons of these wadsetters to follow any other profession

than that of arms and agriculture; and it is in the remembrance of many

now living, when the meanest tenant would think it disparaging to sit at

the same table with a manufacturer."

The following quotation

from the Statistical Account of Rannoch, in Perthshire, will give an idea

of another phase of the life of Highland gentlemen in those days, as well

as enable the reader to see how it was, considering the general poverty of

the country, the low rent, the unproductiveness of the soil, and the low

price of cattle, they were still able to keep open table and maintain more

retainers than the land could support. "Before the year 1745 Rannoch

was in an uncivilized barbarous state, under no check, or restraint of

laws. As an evidence of this, one of the principal proprietors never could

be compelled to pay his debts. Two messengers were sent from Perth, to

give him a charge of horning. He ordered a dozen of his retainers to bind

them across two hand-barrows, and carry them, in this state, to the bridge

of Cainachan, at nine miles distance. His property in particular was a

nest of thieves. They laid the whole country, from Stirling to Coupar of

Angus, under contribution, obliging the inhabitants to pay them Black

Meal, as it is called, to save their property from being plundered. This

was the centre of this kind of traffic. In the months of September and

October they gathered to the number of about 300, built temporary huts,

drank whisky all the time, settled accounts for stolen cattle, and

received balances. Every man then bore arms. It would have required a

regiment to have brought a thief from that country."

As to the education of the

Highland gentry, in this respect they seem not to have been so far behind

the rest of the country, although latterly they appear to have degenerated

in this as in other respects; for, as will be seen in the Chapter on

Gaelic Literature, there must have been at one time many learned men in

the Highlands, and a taste for literature seems not to have been uncommon.

Indeed, from various authorities quoted in the Introduction to Stuart’s Costume

of the Clans, it was no uncommon accomplishment in the 16th and 17th

centuries for a Highland gentleman to be able to use both Gaelic and

Latin, even when he could scarcely manage English. "If, in some

instances," says Mrs Grant, "a chief had some taste for

literature, the Latin poets engaged his attention more forcibly than the

English, which he possibly spoke and wrote, but inwardly despised, and in

fact did not understand well enough to relish its delicacies, or taste its

poetry." "Till of late years," says the same writer on the

same page, "letters were unknown in the Highlands except among the

highest rank of gentry and the clergy. The first were but partially

enlightened at best. Their minds had been early imbued with the stores of

knowledge peculiar to their country, and having no view beyond that of

passing their lives among their tenants and dependants, they were not much

anxious for any other. In some instances, the younger brothers of

patrician families were sent early out to lowland seminaries, and

immediately engaged in some active pursuit for the advancement of their

fortune." In short, so far as education went, the majority of the

Highland lairds and tacksmen appear to have been pretty much on the same

footing with those in a similar station in other parts of the

kingdom.

From what has been said

then as to the condition of the chiefs or lairds and their more immediate

dependants the tacksmen, previous to 1745, it may be inferred that they

were by no means ill-off so far as the necessaries and even a few of the

luxuries of life went. Their houses were certainly not such as a gentleman

or even a well-to-do farmer would care to inhabit now-a-days, neither in

build nor in furnishing; but the chief and principal tenants as a rule had

always plenty to eat and drink, lived in a rough way, were hospitable to

their friends, and, as far as they were able, kind and lenient to their

tenants.

It was the sub-tenants and

cottars, the common people or peasantry of the Highlands, whose condition

called for the utmost commiseration. It was they who suffered most from

the poverty of the land, the leanness of the cattle, the want of trades

and manufactures, the want, in short, of any reliable and systematic means

of subsistence. If the crops failed, or disease or a severe winter killed

the half of the cattle, it was they who suffered, it was they who were the

victims of famine, a thing of not rare occurrence in the Highlands. It

seems indeed impossible that any one now living could imagine anything

more seemingly wretched and miserable than the state of the Highland

subtenants and cottars as described in various contemporary accounts. The

dingiest hovel in the dirtiest narrowest "close" of Edinburgh

may be taken as a fair representative of the house inhabited formerly in

the Highlands by the great mass of the farmers and cottars. And yet they

do not by any means appear to have regarded themselves as the most

miserable of beings, but on the contrary to have been lighthearted and

well content if they could manage to get the year over without absolute

starvation. No doubt this was because they knew no better state of things,

and because love for the chief would make them endure any thing with

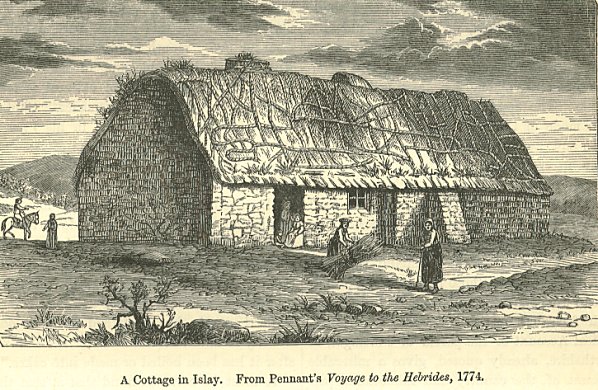

patience. Generally the houses of the sub-tenants and cottars who occupied

a farm were built in one spot, "all irregularly placed, some one way,

some another, and at any distance, look like so many heaps of dirt."

They were generally built in some small valley or strath by the side of a

stream or loch, and the collection of houses on one farm was known as the

"toon" or town, a term still used in Shetland in the very same

sense, and in many parts of Scotland applied to the building occupied by

even a single farmer. The cottages were generally built of round stones

without any cement, thatched with sods, and sometimes heath; sometimes

they were divided into two apartments by a slender partition, but

frequently no such division was made. In the larger half resided the

family, this serving for kitchen, eating, and sleeping-room to all. In the

middle of this room, on the floor, was the peat fire, above which was a

gaping hole to allow the escape of the smoke, very little however of this

finding its way out, the surplus, after every corner of the room was

filled, escaping by the door. The other half of the cottage was devoted to

the use of the live-stock when "they did not choose to mess and lodge

with the family." Sometimes these cottages were built of turf or mud,

and sometimes of wattle-work like baskets, a common system of fencing even

yet in many parts of the Highlands where young wood is abundant. As a rule

these huts had to be thatched and otherwise repaired every year to keep

them habitable; indeed, in many places it was quite customary every spring

to remove the thatch and use it as manure. Buchanan, even in the latter

half of the 18th century, thus speaks of the dwellings of tenants in the

Western Isles; and, in this respect at least, it is not likely they were

in worse plight than those who lived in the early part of the century.

"The huts of the

oppressed tenants are remarkably naked and open; quite destitute of

furniture, except logs of timbers collected from the wrecks of the sea, to

sit on about the fire, which is placed in the middle of the house, or upon

seats made of straw, like foot hassacks, stuffed with straw or stubble.

Many of them must rest satisfied with large stones placed around the fire

in order. As all persons must have their own blankets to sleep in, they

make their beds in whatever corner suits their fancy, and in the mornings

they fold them up into a small compass, with all their gowns, cloaks,

coats, and petticoats, that are not in use. The cows, goats, and sheep,

with the ducks, hens, and dogs, must have the common benefit of the fire,

and particularly the young and tenderest are admitted next to it. This

filthy sty is never cleaned but once a-year, when they place the dung on

the fields as manure for barley crops. Thus, from the necessity of laying

litter below these cattle to keep them dry, the dung naturally increases

in height almost mid-wall high, so that the men sit low about the fire,

while the cattle look down from above upon the company. "We learn

from the same authority that in the Hebrides every tenant must have had

his own beams and side timbers, the walls generally belonging to the

tacksman or laird, and these were six feet thick with a hollow wall of

rough stones, packed with moss or earth in the centre. A tenant in

removing carried his timbers with him to his new location, and speedily

mounted them on the top of four rude walls. But indeed the condition of

many of the Western Isles both before and after 1745 and even at the

present day, was frequently much more wretched than the Highlands in the

mainland generally. Especially was this the case after 1745, although even

before that their condition can by no means be taken as typical of the

Highlands generally. The following, however, from the Statistical Account

of the island of Tiree, might have applied at the time (about 1745), to

almost any part of the Highlands. "About 40 years ago, a great part

of the lands in this parish lay in their natural uncultivated state, and

such of them as were in culture produced poor starved crops. The tenants

were in poor circumstances, the rents low, the farm houses contemptible.

The communication from place to place was along paths which were to be

known by the footsteps of beasts that passed through them. No turnips,

potatoes, or cabbages, unless a few of the latter in some gardens; and a

great degree of poverty, indolence, and meanness of spirit, among the

great body of the people. The appearance of the people, and their mode of

thinking and acting, were but mean and indelicate; their peats were

brought home in creels; the few things the farmer had to sell were carried

to market upon the backs of horses; and their dunghills were hard by their

doors. "We have reliable testimony, however, to prove, that even the

common Highland tenants on the mainland were but little better off than

those in the islands; their houses were almost equally rude and dirty, and

their furniture nearly as scanty. The Statistical Account of the parish of

Fortingal, in Perthshire, already quoted, gives a miserable account of the

country and inhabitants previous to 1745, as does also the letters of

Captain Burt in reference to the district which came under his

observation; and neither of these districts was likely to be in worse

condition than other parts of the Highlands, further removed from

intercourse with the Lowlands. "At the above period [1745], the bulk

of the tenants in Rannoch had no such thing as beds. They lay on the

ground, with a little heather, or fern, under them. One single blanket was

all their bed-cloaths, excepting their body-cloaths. Now they have

standing-up beds, and abundance of blankets. At that time the houses in

Rannoch were huts of, what they called, ‘Stake and Rife.’ One could

not enter but on all fours; and after entering, it was impossible to stand

upright. Now there are comfortable houses built of stone. Then the people

were miserably dirty, and foul-skinned. Now they are as cleanly, and are

clothed as well as their circumstances will admit of. The rents of the

parish, at that period, were not much above £1500, and the people were

starving. Now they pay £4660 per annum, and upwards, and the

people have fulness of bread. It is hardly possible to believe, on how

little the Highlanders formerly lived. They bled their cows several times

in the year, boiled the blood, eat a little of it like bread, and a most

lasting meal it was. The present incumbent has known a poor man, who had a

small farm hard by him, by this means, with a boll of meal for every mouth

in his family, pass the whole year. "This bleeding of the cattle to

eke out the small supply of oatmeal is testified to by many other

witnesses. Captain Burt refers to it; and Knox, in his View of the

British Empire, thus speaks of it:—" In winter, when the

grounds are covered with snow, and when the naked wilds afford them

neither shelter nor subsistence, the few cows, small, lean, and ready to

drop down through want of pasture, are brought into the hut where the

family resides, and frequently share with them their little stock of meal,

which had been purchased or raised for the family only, while the cattle

thus sustained are bled occasionally to afford nourishment for the

children, after it has been boiled or made into cakes."

It must be borne in mind

that at that time potatoes were all but unknown in the Highlands, and even

in the Lowlands had scarcely got beyond the stage of a garden root. The

staple food of the common Highlander was the various preparations of oats

and barley; even fish seems to have been a rarity, but why it is difficult

to say, as there were plenty both in the sea and in freshwater rivers and

lochs. For a month or two after Michaelmas, the luxury of fresh meat seems

to have been not uncommon, as at that time the cattle were in condition

for being slaughtered; and the more provident or less needy might even go

the length of salting a quantity for winter, hut even this practice does

not seem to have been common except among the tacksmen. "Nothing is

more deplorable than the state of this people in time of winter."

Then they were completely confined to their narrow glens, and very

frequently night and day to their houses, on account of the severe snow

and rain storms. "They have no diversions to amuse them, but sit

brooding in the smoke over the fire till their legs and thighs are

scorched to an extraordinary degree, and many have sore eyes and some are

quite blind. This long continuance in the smoke makes them almost as black

as chimney-sweepers; and when the huts are not water-tight, which is often

the case, the rain that comes through the roof and mixes with the

sootiness of the inside, where all the sticks look like charcoal, falls in

drops like ink. But, in this circumstance, the Highlanders are not very

solicitous about their outward appearance. "We need not wonder under

these circumstances at the prevalence of a loathsome distemper, almost

peculiar to the Highlands, and the universality of various kinds of

vermin; and indeed, had it not been that the people spent so much of their

time in the open air, and that the pure air of the mountains, and been on

the whole temperate in drinking and correct in morals, their condition

must have been much more miserable than it really was. The misery seems to

have been apparent only to onlookers, not to those whose lot it was to

endure it. No doubt they were most mercilessly oppressed sometimes, but

even this oppression they do not seem to have regarded as any hardship, as

calling for complaint on their part:- they were willing to endure anything

at the hands of the chief; who, they believed, could do no wrong.

As a rule the chiefs and

gentlemen of the clan appear to have treated their inferiors with kindness

and consideration, although, at the same time, it was their interest and

the practice of most of them to encourage the notions the people

entertained of their duty to their chiefs, and to keep them in ignorance

of everything that would tend to diminish this profitable belief. No doubt

many of the chiefs themselves believed as firmly in the doctrine of

clanship as their people; but there is good reason to believe, that many

of them encouraged the old system from purely interested and selfish

motives. Burt tells us that when a chief wanted to get rid of any

troublesome fellow, he compelled him, under threat of perpetual

imprisonment or the gallows, to sign a contract for his own banishment,

when he was shipped off from the nearest port by the first vessel bound

for the West Indies. Referring no doubt to Lord Lovat, he informs us that

this versatile and long-headed chief acted on the maxim that to render his

clan poor would double the tie of their obedience; and accordingly he made

use of all oppressive means to that end. "To prevent any diminution

of the number of those who do not offend him, he dissuades from their

purpose all such as show an inclination to traffic, or to put their

children out to trades, as knowing they would, by such an alienat on shake

off at least good part of their slavish attachment to him and his family.

This he does, when downright authority fails, by telling them how their

ancestors chose to live sparingly, and be accounted a martial people,

rather than submit themselves to low and mercenary employments like the

Lowlanders, whom their forefathers always despised for the want of that

warlike temper which they (his vassals) still retained, &c. This

cunning chief was in the habit, according to Dr Chambers’s Domestic

Annals, of sending from Inverness and paying for the insertion in the

Edinburgh Courant and Mercury of glaring accounts of feasts

and rejoicings given by himself or held in his honour. And it is well

known that this same lord during his life-time erected a handsome

tombstone for himself inscribed with a glowing account of his heroic

exploits, intended solely for the use of his clansmen. By these and

similar means would crafty selfish lairds keep their tenants and cottars

in ignorance of their rights, and make them resigned to all the oppressive

impositions laid upon them. No doubt Lovat’s was an extreme case, and

there must have been many gradations of oppressions, and many chiefs who

really cared for their people, and did their best to make them happy and

comfortable, although, considering their circumstances and general

surroundings, it is difficult to see how they could succeed. Yet

notwithstanding their miserable and filthy huts, their scanty and poor

food, their tattered and insufficient clothes, their lean cattle and

meagre crops, their country wet above and below, their apparent want of

all amusements and of anything to lighten their cheerless condition, and

the oppressive exactions of their chiefs, the Highlanders as a body

certainly do not seem to have been an unhappy or discontented people, or

to have had any feeling of the discomfort attending their lot. There seems

to have been little or no grumbling, and it is a most remarkable fact that

suicide was and probably is all but unknown among the Highlanders. Your

genuine Highlander was never what could strictly be called a merry man, he

never had any of the effervescence of the French Celt, nor of the

inimitable never-failing light-hearted humour of his Irish brother; but,

on the other hand, under the old system, at heart he showed little or no

discontent, but on the contrary seems to have been possessed of a

self-satisfied, contented cheerfulness, a quiet resignation to fate, and a

belief in the power and goodness of his chief, together with an ignorance

and contempt for all outside his own narrow sphere, that made him feel as

happy and contented as the most comfortable peasant farmer in France. They

only became discontented and sorely cut up when their chiefs,—it being

no longer the interest of the latter to multiply and support their

retainers,— began to look after their own interests solely, and show

little or no consideration for those who regarded them with reverence

alone, and who thought their chief as much bound to support and care for

them and share his land and his bread with them, as a father is to

maintain his children. After the heritable jurisdictions were abolished,

of course everything was changed; but before that there is every reason to

believe that the Highland tenants and cottars were as contented and happy,

though by no means so well off, as the majority of those in the same

condition throughout the United Kingdom. Indeed the evils which prevailed

formerly in the Highlands, like all other evils, look far worse in

prospect (in this case retrospect) than they do in reality. Misery in

general is least perceived by those who are in its midst, and no doubt

many poor and apparently miserable people wonder what charitable

associations for their relief make so much fuss about, for they themselves

see nothing to relieve. Not that this misery is any the less real and

fruitful of evil consequences, and demanding relief; it is simply that

those who are in the midst of it can’t, very naturally, see it in its

true light. As to the Highlands, the tradition remained for a long time,

and we believe does so still in many parts, that under the old regime,

chiefs were always kind as fathers, and the people faithful and loving as

children; the men were tall and brave, and the women fair and pure; the

cattle were fat and plentiful, and the land produced abundance for man and

beast; the summers were always warm, and the winters mild; the sun was

brighter than ever it has been since, and rain came only when wanted. In

short everybody had plenty with a minimum of work and abundance of time

for dancing and singing and other amusements; every one was as happy as

the day was long. It was almost literally "a land flowing with milk

and honey," as will be seen from the following tradition :- "It

is now indeed idle, and appears fabulous, to relate the crops raised here

30 or 40 years ago. The seasons were formerly so warm, that the people

behoved to unyoke their ploughs as soon as the sun rose, when sowing

barley; and persons yet living, tell, that in traveling through the

meadows in the loan of Fearn, in some places drops of honey were seen as

the dew in the long grass and plantain, sticking to their shoes as they

passed along in a May morning; and also in other parts, their shoes were

oiled as with cream, going through such meadows. Honey and bee hives were

then very plenty. . . Cattle, butter, and cheese, were then very plenty

and cheap." This glowing tradition, we fear, must melt away before

the authentic and too sober accounts of contemporaries and eye-witnesses.

As for wages to day-labourers

and mechanics, in many cases no money whatever was given; every service

being frequently paid for in kind; where money was given, a copper or two

a day was deemed an ample remuneration, and was probably sufficient to

provide those who earned it with a maintenance satisfactory to themselves,

the price of all necessary provisions being excessively low. A pound of

beef or mutton, or a fowl could be obtained for about a penny, a cow cost

about 30 shillings, and a boll of barley or oatmeal less than 10

shillings; butter was about two pence a pound, a stone (21 lbs.) of cheese

was to be got for about two shillings. The following extract, from the Old

Statistical Account of Caputh, will give the reader an idea of the rate of

wages, where servants were employed, of the price of provisions, and how

really little need there was for actual cash, every man being able to do

many things for himself which would now require perhaps a dozen workmen to

perform. This parish being strictly in the lowlands, but on the border of

the Highlands, may be regarded as having been, in many respects, further

advanced than the majority of Highland parishes. "The ploughs and

carts were usually made by the farmer himself; with little iron about the

plough, except the colter and share; none upon the cart or harrows; no

shoes upon the horses; no hempen ropes. In short, every instrument of

farming was procured at small expense, wood being at a very low price.

Salt was a shilling the bushel: little soap was used: they had no candles, instead of which they split the

roots of fir trees, which, though brought 50 or 60 miles from the

Highlands, were purchased for a trifle. Their clothes were of their own

manufacturing. The average price of weaving ten yards of such cloth was

a shilling, which was paid partly in meal and partly in money. The

tailor worked for a quantity of meal, suppose 3 pecks or a firlot

a-year, according to the number of the farmer’s family. In the year

1735, the best ploughman was to be had for L.8 Scots (13s. 4d.) a year,

and what was termed a bounty, which consisted of some articles of

clothing, and might be estimated at 11s. 6d. ; in all L.1, 4s. 10d.

sterling. Four years after, his wages rose to L.24 Scots, (L.2) and

the bounty. Female servants received L.2 Scots, (3s. 4d.) and a bounty

of a similar kind; the whole not exceeding 6s. or 7s. Some years after

their wages rose to 15s. Men received for harvest work L.6 Scots,

(10s.);

women, L.5 Scots, (8s. 4d.). Poultry was sold at 40 pennies Scots,

(3½d.) Oat-meal, bear and oats, at L.4 or L.5 Scots the boll. A horse

that then cost 100 merks Scots, (L.5 : 11 : 1¾) would now cost L.25. An

ox that cost L.20 Scots, (L.1 : 13 : 4) would now be worth L.8 or L.9. Beef

and mutton were sold, not by weight, but by the piece; about 3s. 4d. for

a leg of beef of 3½ stones; and so in proportion. No tea nor sugar was

used: little whisky was drunk, and less of other spirits: but they had plenty of

good ale; there being usually one malt barn (perhaps two) on each

farm."

When a Highlander was in need of anything which he

could not produce or make himself, it was by no means easy for him to obtain it, as by

far the greater part of the Highlands was utterly destitute of towns and

manufactures; there was little or no commerce of any kind. The only

considerable Highland town was Inverness, and, if we can believe Captain

Burt, but little

business was done there; the only other places, which made any pretensions to be towns

were Stornoway and Campbeltown, and these at the time we are writing of, were little better

than fishing villages. There were no manufactures strictly speaking, for

although the people spun their own wool and made their own cloth,

exportation, except perhaps in the case of stockings, seems to have been

unknown. In many cases a system of merchandise some what similar to the

ruinous, oppressive, and obstructive system still common in Shetland, seems to

have been in vogue in many parts of the Highlands. By this system, some of the

more substantial tacksmen would lay in a stock of goods such as would be likely

to be needed by their tenants, but which these could not procure for themselves,

such as iron, corn, wine, brandy, sugar, tobacco, &c. These goods the

tacksmen would supply to his tenants as they needed them, charging nothing for

them at the time; but, about the month of May, the tenant would hand over to his

tacksman-merchant as many cattle as the latter considered an equivalent for the

goods supplied. As the people would seldom have any idea of the real value of

the goods, of course there was ample room for a dishonest tacksman to realise an

enormous profit, which, we fear, was too often done. " By which traffic the

poor wretched people were cheated out of their effects, for one half of their

value; and so are kept in eternal poverty."

As to roads, with the exception

of those made for military purposes by General Wade, there seems to have been

none whatever, only tracts here and there in the most frequented routes,

frequently impassable, and at all time unsafe without a guide. Captain Burt

could not move a mile or two out of Inverness without a guide. Bridges seem to

have been even rarer than slated houses or carriages.

We have thus endeavoured to give

the reader a correct idea of the state of the country and people of the

Highlands previous to the abolition of the heritable jurisdictions. Our only aim

has been to find out the truth, and we have done so by appealing to the evidence

of contemporaries, or of those whose witness is almost as good. We have

endeavoured to exhibit both the good and bad side of the picture, and we are

only sorry that space will not permit of giving further details. However, from

what has been said above, the reader must see how much had to be accomplished by

the Highlanders to bring them up to the level of the rest of the country, and

will be able to understand the nature of the changes which from time to time

took place, the difficulties which had to be overcome, the prejudices which had

to be swept away, the hardships which had to be encountered, in assimilating the

Highlands with the rest of the country.

Having thus, as far as space

permits, shown the condition of the Highlands previous to 1745, we shall now, as

briefly as possible, trace the history down to the present day, showing the

march of change, and we hope, of progress after the abolition of the heritable

jurisdictions. In doing so we must necessarily come across topics concerning

which there has been much rancorous and unprofitable controversy; but, as we

have done in the case of other disputed matters, we shall do our best to lay

facts before the reader, and allow him to form his opinions for himself. The

history of the Highlands since 1745 is no doubt in some respects a sad one; much

misery and cruel disappointment come under the notice of the investigator. But

in many respects, and, we have no doubt in its ultimate results, the history is

a bright one, showing as it does the progress of a people from semi-barbarism

and slavery and ignorance towards high civilisation, freedom of action with the

world before them, and enlightenment and knowledge, and vigorous and successful

enterprise. Formerly the Highlanders were a nuisance to their neighbours, and a

drag upon the progress of the country; now they are not surpassed by any section

of her Majesty’s subjects for character, enterprise, education, loyalty, and

self-respect. Considering the condition of the country in 1745, what could we

expect to take place on the passing and enforcing of an act such as that which

abolished the heritable jurisdictions? Was it not natural, unavoidable that a

fermentation should take place, that there should be a war of apparently

conflicting interests, that, in short, as in the achievement of all great

results by nations and men, there should be much experimenting, much groping to

find out the best way, much shuffling about by the people to fit themselves to

their new circumstances before matters could again fall into something like a

settled condition, before each man would find his place in the new adjustment of

society? Moreover, the Highlanders had to learn an inevitable and a salutary

lesson, that in this or in any country under one government, where prosperity

and harmony are desired, no particular section of the people is to consider

itself as having a right to one particular part of the country. The Highlands

for the Highlanders is a barbarous, selfish, obstructive cry in a united and

progressive nation. It seems to be the law of nature, as it is the law of

progress, that those who can make the best use of any district ought to have it.

This has been the case with the world at large, and it has turned out, and is

still turning out to be the case with this country. The Highlands now contain a

considerable lowland population, and the Highlanders are scattered over the

length and breadth of the land, and indeed of the world, honourably fulfilling

the noble part they have to play in the world’s history. Ere long there will

be neither Highlander nor Lowlander; we shall all be one people, having the best

qualities of the blood of the formerly two antagonistic races running in our

veins. It is, we have no doubt, with men as with other animals, the best breeds

are got by judicious crossings.

Of course it is seldom the case

that any great changes take place in the social or political policy of a country

without much individual suffering: this was the case at all events in the

Highlands. Many of the poor people and tacksmen had to undergo great hardships

during the process of this new adjustment of affairs; but that the lairds or

chiefs were to blame for this, it would be rash to assert. Some of these were no

doubt unnecessarily harsh and unfeeling, but even where they were kindest and

most considerate with their tenants, there was much misery prevailing among the

latter. In the general scramble for places under the new arrangements, every

one, chief, tacksman, tenant, and cottar, had to look out for himself or go to

the wall, and it was therefore the most natural thing in the world that the

instinct of self-preservation and self-advancement, which is stronger by far

than that of universal benevolence, should urge the chiefs to look to their own

interests in preference to those of the people, who unfortunately, from the

habit of centuries, looked to their superiors alone for that help which they

should have been able to give themselves. It appears to us that the results

which have followed from the abolition of the jurisdictions and the obliteration

of the power of the chiefs, were inevitable; that they might have been brought

about in a much gentler way, with much less suffering and bitterness and

recrimination, there is no doubt; but while the process was going on, who had

time to think of these things, or look at the matter in a calm and rational

light? Certainly not those who were the chief actors in bringing about the

results. With such stubbornness, bigotry, prejudice, and ignorance on one side,

and such power and poverty and necessity for immediate and decided action on the

other, and with selfishness on both sides, it was all but inevitable that

results should have been as they turned out to be. We shall do what we can to

state plainly, briefly, and fairly the real facts of the case. |