|

The houses of Scott and

Douglas, of Buccleuch and Queensberry, have long been connected by ties of

blood and friendship. Janet, daughter of David Scott of Branxholm, and Sir

James Douglas of Drumlanrig, by their marriage in the year 1470, became

the common ancestors of the two families. In later days these houses were

still more closely allied. Francis, son of James, Earl of Dalkeith, who

married Henrietta Hyde, daughter of the Earl of Rochester, inherited the

Dukedom of Buccleuch through his grandmother Anna. He in turn married Lady

Jane Douglas, eldest daughter of the second Duke of Queensberry, and thus

the third Duke of Buccleuch succeeded in 1810 to the Queensberry title as

well.

The name of Douglas has

inspired poets, dramatists, and historians, from Scott and Home downwards,

[“Douglas, a name

through all the world renoun’d –

A name that rouses like the trumpet’s

sound! –

Oft have your fathers, prodigal of life,

A Douglas followed through the bloody strife.”

- The

Tragedy of Douglas (Prologue.)]

to the most enthusiastic eulogies in prose and verse,

and an old rhymed saying, long common in the mouths of Scotsmen, declared

that –

“So many, so good as the

Douglasses have been

Of one sirname were never

in Scotland seen.”

An early biographer of the

Douglas family, writing in the middle of the eighteenth century, traces

their pedigree as far back as the days of Pharaoh, King of Egypt, the

father of that monarch who pursued Moses with such malignant fidelity.

According to this historian, a certain Gathaleus was the general of

Pharaoh’s troops, who, with the assistance of his lieutenant Sayas,

succeeded in defeating the ever-hostile forces of the Ethiopians. As a

reward for this victory he was given the hand of Pharaoh’s daughter Scota.

Gathaleus and his bride journeyed to Portugal, where they were joined by

the faithful Sayas, and the descendants of these two families eventually

came to Scotland and founded the house of Douglas. [The History and

Martial Achievements of the Houses of Douglas, Angus, and Queensberry,

p. v. (Edinburgh, 1769.)] “I shall add no more,” says this old

chronicler, with an exhibition of self-restraint all the more commendable

in one who obviously possessed so exceptionally vivid an imagination, “but

give me Leave to ask all Christian Kings, Princes, and Noblemen, and the

Flatterers who have wrote their Genealogies, conquests, Exploits and

Battles, if they can produce a family equal in Nobility, antiquity, and

Valour to the House of Douglas?” “What family,” he asks, “ever did,

in Favour of their Country, what the Douglasses have done for the

Honour and Advantage of Scotland?” [Ibid., p.xix]

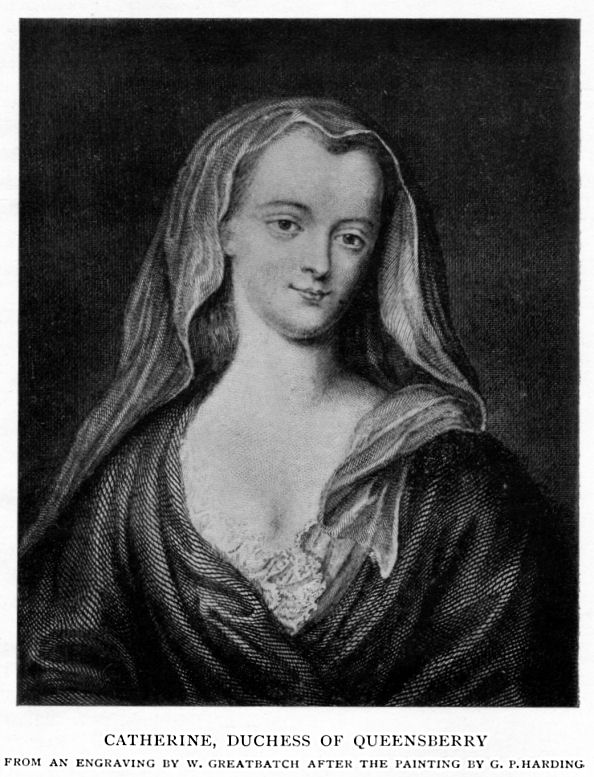

On the 10th of

March, 1720, Charles Douglas, 3rd Duke of Queensberry, a Privy

Councillor, and Lord of the Bedchamber to George I., married Lady

Catherine Hyde, second daughter of Henry, Lord Hyde, who afterwards

succeeded to the earldoms of Rochester and Clarendon.

Lady Kitty was already one

of the reigning toasts of her day. Her mother, a lovely woman whom Prior

has immortalised as Myra in his Judgment of Venus, bequeathed her

good looks to at least two of her eight children, - to Kitty, whose beauty

was no less famous than her eccentricities, and to Jane, the “Blooming

Hyde, with eyes so rare,” mentioned by Gay in the prologue to his

Shepherd’s Week.

It may be urged that Kitty,

Duchess of Queensberry, has no right to a place in these pages, since she

was not by birth a Scotswoman. Indeed, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was

malicious enough to suggest that she was not even a Hyde, but the daughter

of Lord Carleton, - a calumny for which there does not seem to be the

slightest justification. But if the duchess was not of Scottish birth, her

husband was a Scotsman, and she herself was such a well-known figure in

the society of the Scottish capital that the inclusion of her name in a

list of the notable Scottish women of the past may perhaps be pardoned.

Of the duchess’s early life

there is little record. It is said, on I know not what authority, that she

was at one period confined in a strait-waistcoat, and by her crazy conduct

in later years she certainly seems to have deserved, if she did not

actually obtain, an occasional dose of physical restraint. A whole chapter

could easily be filled with an account of her various eccentricities.

Horace Walpole, who, though he lived to alter his opinion, was not at one

time particularly fond of her, [“Thank God! The Thames is between me

and the Duchess of Queensberry!” – The Letters of Horace Walpole,

Edited by Peter Cunningham, vol. ii. p86. (1857.)] relates a typical

story of her Grace driving off post-haste to Parson’s Green to Lady Sophia

Thomas, bearing news, as she declared, of paramount importance. “What is

it?” asked the astonished Lady Sophia. “Why,” replied the duchess, “take a

couple of beefsteaks, clap them together as if they were for a dumpling,

and eat them with pepper and salt; it’s the best thing you ever tasted: I

couldn’t help coming to tell you!” [Ibid., p.161] And away she

drove back to town! (In this story the duchess reminds one of the

night-watchman in one of Max Adeler’s tales who used to wake people up in

the middle of the night to remark that bananas were the best bait for

cat-fish.) Walpole’s only comment on such conduct is that “a course of

folly makes one very sick!”

At a ball which the duchess

gave at Drumlanrig the guests were all assembled and the band had started

playing when the hostess suddenly declared that she was suffering from a

headache and could not bear the noise. The dancing was stopped then and

there, to the great disgust of the assembled company. Lord Drumlanrig had,

fortunately, some experience of his mother’s peculiarities, and knew how

to deal with them. He at once proceeded to seize the big armchair in which

the duchess was sitting, and ran it violently round the room two or three

times, saying that this was by far the best treatment for a headache.

Whereupon his mother realised the humour of the situation, admitted that

her temporary indisposition was cured, and graciously allowed the dance to

proceed.

The duchess always appears

to have found peculiar scope in the ballroom for a display of her

eccentricities. At a masquerade which she once gave at her house in

London, she had large notices containing regulations as to the conduct of

the dance posted all over the walls, turned half her guests out of the

house at midnight, kept the remainder to supper, and, in short, as Walpole

tells us, “continued to do an agreeable thing in the rudest manner

imaginable.” [The Letters of Horace Walpole, vol. ii. p.86.] On

this occasion, too, she insisted on dressing her husband up in Scottish

costume, which was then – it was only a few years after the Rebellion of

’45 – considered particularly offensive, if not openly disloyal.

She herself made a point of

wearing at all times the garb of a Scottish peasant woman, and was

curiously surprised at the uncomplimentary comment it evoked. [“Everybody’s

eye would strike them that my dress was exactly according to form,” she

writes, “if their ears had not been (by some ill accident or other) used

to hear it unjustly condemned.” – Letters to and from Henrietta,

Countess of Suffolk, vol. ii. p.99] On account of this habit of

hers and edict was issued forbidding ladies to appear at Court in aprons.

The duchess decided, however, to ignore it, and gaily presented herself at

the next Drawing-room attired in her usual simple dress, which, becoming

as it was, must have looked singularly out of place at St. James’s. The

lord-in-waiting on duty attempted to stop her at the door, explaining as

politely as possible that she could not be admitted in an apron. Whereupon

the duchess lost her temper, tore off the offending garment, flung it in

his lordship’s astonished face, and strode into the circle dressed in her

rustic gown and petticoat. Such conduct naturally gave rise to

unflattering criticism.

Again, when in her official

capacity as lady-in-waiting the duchess was present one day in the Queen’s

room while her majesty was dressing, she was suddenly so completely

overcome with the humour of the situation that she was obliged to creep

out of the window on hands and knees, in order to avoid giving way in the

royal presence to an outburst of indecorous laughter. Her breaches of

court etiquette were the result of light-heartedness and a frivolous

disposition; they were not due to lack of education or savoir faire

as in the case of her predecessor, Jane Warburton, Duchess of Argyll. [Jane

was maid of honour to Queen Anne and afterwards to Queen Caroline, and,

though well-born, was very indifferently educated. The removals of the

court from palace to palace were superintended by a state official known

as the “Harbinger.” On one occasion, when the ladies-in-waiting, on a

rumour of a sudden move to Windsor, were consulting together about their

baggage, “Well, for my part,” said Jane, “I shan’t trouble myself. Must

not the ‘Scavenger’ take care of us maids of honour?” Letters and

Journals of Lady Mary Coke, edited by the Hon J.A. Home, vol. iii.

p.423] Lady Mary Coke, in her Journal, gives an account of an

afternoon call paid on her in 1768 by the Duchess of Queensberry, who was

then an elderly woman. Lady Mary happened to remark that she had heard of

her Grace dancing at a ball at Gunnersbury, but had not had the pleasure

of seeing her. “You may see me now,” said the old lady, and immediately

proceeded to skip round the room with amazing agility. [Ibid., vol. ii.

p.345]

The duchess’s practice of

wearing clothes which were unsuited to her rank and position often got her

into trouble at other places besides the Court. She once arrived at a

military review dressed in her customary garb, and on trying to approach

the duke was rudely pushed back into the crowd by one of the sentries who

had naturally failed to recognise the great lady so disguised. Her fury at

this insult was only appeased when her husband promised that a sound

flogging should be administered to every man of the guard as a lesson in

the folly of judging by appearances.

To the end of her life the

duchess remained loyal to the fashion in dress which was in vogue when she

was a girl, and flatly declined to make any change in her costume. Being a

singularly handsome woman, she could afford to be eccentric on this point.

Whitehead the poet, to whom she declared that the frequent alteration in

feminine fashions was merely a lure to catch male attention, admitted this

when he wrote the following verse in reply:-

“Your Grace will contradict

in part

Your own assertion, and my

song,

Whose beauty, undisguised

by art,

Has charmed so much, and

charmed so long.”

The lively Kitty was always

in the very best of spirits –“the cheerful Duchess,” Gay called her [“Yonder

I see the cheerful duchess stand,

For friendship, zeal,

and blithesome humours known.”] – and

combined a strong sense of humour with great tenderness of heart. Many of

her friends had experience of her kindly nature. When old Lady Lichfield

was stricken with blindness, the duchess would go and sit by her bedside

night after night, cheering the invalid with her amusing society and that

ceaseless flow of gossip and anecdote with which her conversation

sparkled. Though a sweet-tempered woman as a rule, there was one thing

that never failed to rouse her righteous indignation. “I declare to you,

she writes in one of her letters to Dean Swift, “nothing ever enlivened me

half so much, as unjust ill-usage, either directed to myself or to my

friends.” This hatred of injustice and oppression caused her to become

involved in the case of the poet Gay when his play Polly was

prohibited by the Lord Chamberlain. She warmly espoused the cause of the

dramatist, and consequently both she and the duke fell into dire disgrace

in high quarters.

Gay had scored a huge

success by his Beggar’s Opera, which was acted in London for

sixty-three nights – a long run in those days – and afterwards scored a

similar triumph in the provinces. The Italian Opera, then at the height of

its popularity, unable to compete with Gay’s rival production, was forced

to close its doors. Such was the enthusiasm evoked by the Beggar’s

Opera that (according to Pope’s notes to the Dunciad) “ladies

carried about with them the favourite songs of it in fans, and houses were

furnished with it in screens.” The actress who took the part of Polly rose

from obscurity to fame, rapidly became the favourite of the town, and her

pictures were engraved – this was long before the days of pictorial

post-cards! – and sold in great numbers. But when the play was published,

certain puritanical persons, notably Dr. Herring, afterwards Archbishop of

Canterbury, condemned it as vicious and likely to prove subversive of

public morality. The fact that the hero was a highwayman and that he went

unpunished, was, in the eyes of these critics, a distinct encouragement of

vice. When, therefore, Gay wished to produce a sequel entitled Polly,

the authorities declined to license it. The forbidden play was

consequently published by private subscription in 1728, and the Duchess of

Queensberry exerted herself violently on the author’s behalf, even going

so far as to solicit subscriptions within the sacred precincts of St.

James’s. Writing to Swift on the subject of the unsuccessful efforts made

by the duchess to have the embargo removed from his play, Gay says that

she was allowed to have shown “more spirit, more honour and more goodness,

more understanding and good sense” than was thought possible in those

times. [The Works of Jonathan Swift, edited by W. Scott, vol. xvii.

P.269 (Edin., 1814)]

So anxious was the duchess

to secure a licence for her poet that she even offered to read the play to

King George in his closet, so as to satisfy his Majesty that there was no

harm in it. But the King laughingly declined this offer, saying that he

would be delighted to receive her Grace in his closet, but hoped to amuse

her there better than by the literary employment she proposed. [Ibid.,

vol. xvii. P.199]

At last, owing to her

continued importunity, the duchess was forbidden to appear at court. This

punishment she accepted with her usual cheerfulness. When Lord Hervey said

to her that, now she was banished, the palace had lost its chief ornament,

“I am entirely of your mind,” she replied. [The Autobiography and

Correspondence of Mrs. Delaney, edited by Lady Llanover (1862), vol. i.

p.199] And to the Vice-Chamberlain, whose duty it was to inform her

that his Majesty had reluctantly determined to dispense with her society,

she wrote a most spirited and characteristic letter. “The Duchess of

Queensberry is surprised and well pleased,” she wrote, “that the King hath

given her so agreeable a command as to stay from Court, where she never

came for diversion, but to bestow a civility on the King and Queen; she

hopes by such an unprecedented order as this is that the King will see as

few as he wishes at his Court, particularly such as dare to think or speak

truth. I dare not do otherwise, and ought not nor could have imagined that

it would not have been the very highest compliment that I could possibly

pay the King to endeavour to support truth and innocence in his house,

particularly when the King and Queen both told me that they had not read

Mr. Gay’s play. I have certainly done right, then, to stand by my own

words, rather than his Grace of Grafton’s, who hath neither made use of

truth, judgment, nor honour, through this whole affair, either

for himself or his friends.” [Autobiography of Mrs. Delaney, vol. i.

p.194.]

The Duke of Queensberry

also sided with Gay in this affair, and showed his disapproval of the

position taken up by the King by resigning all his appointments. Including

that of Vice-Admiral of Scotland. He shortly afterwards attached himself

to Frederick, Prince of Wales, then in opposition to the King, and was

appointed one of his Royal Highness’s Lords of the Bedchamber.

The persecuted Gay was

invited to take up his quarters with the Queensberry family, and spent the

remainder of his life under their protection. At “Jenny’s Ha’,” a famous

Edinburgh tavern opposite Queensberry House, the poet might often be seen

in the company of Allan Ramsay and other congenial cronies. The duke

undertook the management of his financial affairs; the duchess nursed him

when he was ill, and both of them treated him, as he says in one of his

letters, as though he had been their nearest relation or their dearest

friend. [Swift’s Works, vol. xvii. P.268.] He became

secretary to the duchess, and no doubt helped her to manage the little

theatre which she had fitted up in Queensberry House, where dramatic

performances were frequently given for the entertainment of her guests.

In 1739, ten years after

the Polly affair, the duchess once again came into collision with

the authorities, when she headed a party of intrepid ladies who

successfully stormed the gallery of the House of Lords. The Peers had

unanimously resolved to exclude ladies from a gallery which had long been

assigned to their use, but was now kept for members of the House of

Commons. But a number of fearless dames, led by the Duchess of Queensberry

in person, presented themselves at nine o’clock one morning at the door of

the House and peremptorily demanded the right of entrance. Sir William

Saunderson, the official on duty, politely informed the deputation that

the Lord Chancellor had issued an order forbidding their admittance, and

that it was consequently impossible for his to let them in. Vainly did the

duchess cajole and wheedle; the obdurate Black Rod declined to change his

mind. When at last she tried the effect of threats, Sir William lost his

temper and said that “By G-! they should never enter the House!” The

duchess replied with equal indignation that “By G-! they would, in

spite of the Lord Chancellor and the whole House of Peers!” Sir William

reported this altercation to the Chancellor, and it was determined to keep

the doors shut, and thus starve the ladies into submission or induce them

to give up and go home. These inexorable females were not, however, to be

got rid of so easily. They sent out to an adjacent cookshop, procured a

supply of provisions, and manfully stood their ground from nine in the

morning till five o’clock at night. By this time, of course, a huge crowd

had gathered to watch the fun, and, while some of its members jeered at

the ladies, others urged them to continue the siege, and even encouraged

them by thumping loudly upon the doors of the House. Seeing that violent

methods were not likely to prove effective, and having perhaps more regard

for decorum than those modern “suffragettes” whose methods they to a

certain extent anticipated, the duchess and her friends determined to

accomplish their purpose by means of a ruse. They accordingly made up

their minds to keep perfectly silent for the space of half-an-hour – a

task which would tax the powers of endurance of the least garrulous of

their descendants. At the end of this period the Chancellor, unaccustomed

to such self-control on the part of the fair sex, came to the conclusion

that the besieging party had gone home. He thereupon ordered the door to

be opened, and the ladies, who had been awaiting this opportunity with

exemplary patience, rushed in immediately, took possession of the gallery,

and celebrated their victory in a thoroughly feminine and illogical

fashion by interrupting the debate with laughter and conversation.

[Letters and Works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, edited by Lord

Wharncliffe, vol. ii. p.37. (1861.)]

When Gay died, [A.D.

1732. (“Unpensioned with a hundred friends.” –The Dunciad.)] the

duchess, who had long been his best friend was very deeply affected. “It

is not possible to imagine the loss his death is to me,” she wrote, “but

as long as I have any memory, the happiness of ever having such a friend

can never be lost to me.” [Swift’s Works, vol. xviii. P.151.]

And again, two years later, “I often want poor Mr. Gay,” she says; “his

loss was really great, but it is a satisfaction to have once known so good

a man.” [Life of Alexander Pope, by P. Carruthers, p.300. (1862)]

The poet died in the Duke of Queensberry’s house, and was honoured by a

magnificent funeral at his patron’s expense. On his tomb in Westminster

Abbey was engraved, by his own express desire, the famous if frivolous

couplet from one of his letters to Pope:-

“Life is a jest, and all

things show it;

I thought so once, and now

I know it.”

And the duchess induced the author of the Dunciad

to write a suitable epitaph for the monument which she erected in the

Abbey to her favourite’s memory.

The Queensberrys were

eventually pardoned for their share in the affair of Gay and his forbidden

drama, and in 1747 we hear of the duchess once more attending the Court.

[Autobiography of Mrs. Delaney, ii. p.469.] She was also present at

a royal party given in 1749 by the Duke of Cumberland at Richmond, where

Walpole met her, “in the middle of all the principalities and powers,” in

her usual “forlorn trim, white apron and white hood.” [Walpole’s

Letters, ii. p.161.] When George III. ascended the throne the

reinstatement of the Queensberrys to royal favour was complete. The duke

regained his seat on the Privy Council, and was appointed Keeper of the

Great Seal of Scotland, and, later on, Lord Justice-General. The Queen

paid a visit to the duchess, who in turn appeared at a Drawing-room – for

the first time for forty years – in such high spirits that she could not

resist committing many minor breaches of court etiquette.

The excitement occasioned

at this time by the famous “Douglas Cause” was shaking society to its very

foundations. Public feeling ran high, especially between the kinsmen and

supporters of the houses of Hamilton and Douglas, who were now called upon

to range themselves behind the chiefs of their respective families. When

the Duke of Douglas died in 1761, his estates, devolved upon his nephew

Archibald, the only surviving son of Lady Jane Douglas. But the Duke of

Hamilton, suspecting that this was a suppositious child, endeavoured to

assail his claims, and affirmed that Archibald was not the son of Lady

Jane at all. The case lasted for seven years, and during this time the

excitement as to the issue of the trial was intense both in Edinburgh and

London. Home, the dramatist, attributes the failure of his play, The

Fatal Discovery, to the lack of public interest in anything but the

Douglas Cause, [Autobiography of Alexander Carlyle, p.509] his

former tragedy, Douglas, having been so popular as to evoke from an

excited Scotsman in the gallery the celebrated remark: “Whaur’s your

Wullie Shakespeare noo?” The Douglas Cause was indeed for a long time the

only topic of conversation in Edinburgh, and elicited the most violent

expressions of opinion from quite unexpected quarters. The old

Dowager-Countess of Stair, one of the most interesting characters in

Edinburgh society, round whose personality Walter Scott built his story of

Aunt Margaret’s Mirror, was as staunch a supporter of the Douglas

family as the Duchess of Queensberry herself. In the evidence adduced at

the trial was an account given by Sir John Stewart of Castlemilk of Lady

Stair coming into a room in the Duke of Hamilton’s house with a letter in

her hand from the Earl of Dundonald in which he accused her of saying that

the children of Lady Jane Douglas were fictitious. The old lady was

terribly excited, and struck the floor three times with her stick, with

every stroke calling the Earl a “d------d villain.” [This Lady Stair

must not be confused with Margaret, Viscountess Stair, who died in 1692,

and was suspected by the public of possessing necromantic powers. She,

too, was an eccentric woman, and ordained in her will that her body should

not be buried, but should stand upright in her coffin, promising that as

long as it remained in that position the Dalrymples should continue to

flourish. (See Chambers’s Domestic Annals of Scotland, vol. iii.

p47.) To this Lady Stair is attributed the witty reply to Graham of

Claverhouse, (commonly pronounced Clavers), the persecutor of the

Covenanters, who had been inveighing against John Knox. “Why are ye so

severe?” asked the old lady. “Ye are both reformers. He gained his

point by clavers (talk) while you attempt to gain yours by Knocks!” (Sir

Walter Scott tells this story in Old Mortality, making old Lady

Elphinstone the heroine of it.)]

The claims of Archibald

Douglas were finally upheld by the House of Lords, and the Duchess of

Queensberry signalised this family triumph by giving a ball to all her

supporters in her house in London. This entertainment was a very

magnificent and successful affair. Lord Camden, the Lord Chancellor,

invited himself, and afterwards wrote to the duchess asking permission to

come in person and thank her for having sent an invitation to his wife and

daughters, who were unable to be present. To this request the duchess sent

the laconic reply: “Catherine Queensberry says ‘Content upon her honour,’”

that being the form of assent given by the Peers at the close of the great

case. [Lady Mary Coke’s Journal, vol. iii. p.40]

The duchess was not always

so polite to those of her guests who tried to thrust their society upon

her. She once told Lady Di Egerton, daughter of the Duchess of Bridgwater,

that she would give a dance in her honour. But when the ball invitations

were sent out, none reached the expectant Lady Di. Thereupon some member

of the girl’s family wrote to her Grace to point out this neglect, which

was obviously and oversight, and received the following stinging reply:-

“The advertisement came to

hand: it was very pretty and very ingenious; but everything that is pretty

and ingenious does not always succeed: the Duchess of Q. piques herself on

her house not being unlike Socrates’s; his was small and held all his

friends; hers is large, but will not hold half of hers; postponed, but not

forgot; unalterable.” [Walpole’s Letters, ii. p.241]

The Duchess could, indeed,

be extremely rude if she thought that the conduct of her acquaintances

required correction. Her comments could be as biting, as caustic, and as

satirical as those of old Lady Rosslyn herself. [Lady Rosslyn was “at

home” to her friends one afternoon when a rather notorious woman was

announced. Immediately several of her guests rose to go. “Sit still, sit

still,” said the old lady, “it is na catching!”] When paying an

afternoon call, if in her opinion the tea-set of her hostess was too

extravagant, the duchess would upset it on the floor, as though by

accident, and break it. Ladies who came to see her in Scotland, dressed in

their best clothes, would be taken for long walks through the dirtiest

lanes she could find, and at the end of the afternoon the duchess would

suddenly seat herself on a convenient manure-heap and invite her guests to

sit beside her, which some of them, out of sheer fright, consented to do.

At Queensberry House, in

the Canongate, Edinburgh, and at Drumlanrig Castle, in Dumfriesshire, the

duchess spent much of her time. Both houses had been built by the first

duke, and eccentric individual, who only slept one night at Drumlanrig,

and is said to have left the bills for the building of that place tied up

with an inscription: “The Deil pyke out his een that looks therein!” [Chambers’s

Traditions of Edinburgh.] In connection with Queensberry House –

where, after Prince Charlie’s victorious entry into Edinburgh during the

’45, the loyal officers were imprisoned, and which is now a Refuge for the

Destitute – a horrible story is told of the idiot son of James, 2nd

Duke of Queensberry, one of the main instruments in carrying out the Union

of England and Scotland. On the day that the Bill for the Union was

passed, all Edinburgh went to the Parliament Close to hear the result of

the debate. The idiot Lord Drumlanrig was left behind, with nobody to look

after him but a little scullery-boy. On the return of the family to

Queensberry House, they were horrified to discover the wretched maniac

engaged in cooking the boy, whom he was roasting on one of the kitchen

spits.

The duchess was devoted to

her Scottish homes, but did not altogether approve of Scottish manners.

One practice in particular – equally prevalent at that time in England –

she especially detested. This was the dangerous and unattractive habit

which some of her guests indulged in of conveying food from their plates

to their mouths with a knife in place of a fork. “I have not met with any

one in this country,” she writes to Lady Suffolk, in 1734, from Edinburgh,

“who doth not eat with a knife, and drink a dish of tea.” [Letters

to and from Henrietta, Countess of Suffolk, vol. ii. p.67. (1824.)

Gay wrote to Swift in 1727, when the latter had been invited to Amesbury,

begging him for the duchess’s sake to put his fork to all its proper uses,

and “suffer nobody for the future to put their knives in their mouths.” [Swift’s

Works, xviii. P.137.] Swift, in replying, asked Gay to tell her

Grace that he always thought of her when he dined, although it was

difficult to obey her injunctions when the forks had only two prongs and

the sauce was not “very consistent.” He received many invitations to stay

with the duchess – a “lady of excellent sense and spirits,” as he tells

Pope – whom he had not seen since she was a girl of five; but was never

able to avail himself of them. Kitty and her secretary used to collaborate

in a most amusing correspondence with Swift. Gay would concoct the main

body of the letter, to which the duchess added a piquant postscript. She

was always pressing her correspondent to pay her a visit, declaring

herself convinced that hostess and guest would get on well together. “The

duke is very much yours,” she writes, as a further inducement to the

convivial dean, “and will never leave you to your wine!” – a

reference probably to a habit of the parsimonious Pope, who would produce

a pint of wine for two guests, help himself to a couple of glasses, and

then retire, saying, “Gentlemen, I leave you to your wine!” [Life of

Alexander Pope, p.409.]

In 1731 we find the duchess

once more urging Swift to visit her. “I only love my own way,” she says,

“when I meet not with others whose ways I like better. I am in great hopes

that I shall approve of yours; for, to tell you the truth, I am at present

a little tired of my own. I have not a clear or distinct voice, except

when I am angry; but I am a very good nurse, when people do not fancy

themselves sick… Pray set out the first fair wind, and stay with us as

long as ever you please… If I do not happen to like you,” she adds, with

characteristic candour, “I know I can so far govern my temper as to endure

you for about five days.” [Swift’s Works, xvii. p.409] Later

on in the same year she again writes to him, with the assurance that

though she is “neither healthy nor young,” she manages to keep up her

spirits and lives as simply as possible. She has no objection to his

talking nonsense, she declares, provided he does it on purpose; for “there

is some sense in nonsense, when it does not come by chance.” [Ibid.,

xvii. p.407.] In spite of these constant lures, Swift declined to

renew his early acquaintance with the duchess, save through the

unsatisfactory medium of the post.

As a girl the beautiful

Kitty had wrung a thousand eulogistic verses from the pens of all the

poets of the day, from Pope,

[“The exactest tricks of

body or of mind,

We owe to models of an

humble kind.

If Queensbury to strip

there’s no compelling,

‘Tis from a handmaid we

must take a Helen.”

-Moral Essays.]

to Congreve. Prior described her début in society in a

poem which is as well known as anything he wrote:-

THE FEMALE PHAETON

Thus Kitty, beautiful and

young,

And wild as colt untam’d,

Bespoke the fair from

whence she sprung,

With little rage inflam’d:

Inflam’d with rage at sad

restraint,

Which wise mamma ordain’d;

And sorely vext to play the

saint,

Whilst wit and beauty

reign’d:

“Shall I thumb holy books,

confin’d

With Abigails forsaken?

Kitty’s for other things

design’d,

Or I am much mistaken.

“Must Lady Jenny frisk

about,

And visit all her cousins?

At balls must she make all

the rout,

And bring home hearts by

dozens>

“What has she better, pray,

than I,

What hidden charms to

boast,

That all mankind for her

should die:

Whilst I am scarce a toast?

“Dearest mamma! for once

let me,

Unchain’d my fortune try;

I’ll have an Earl as well

as she, [Lady Jane Hyde married the Earl of Essex.]

Or know the reason why.

“I’ll soon with Jenny’s

pride quit score,

Make all her lovers fall;

They’ll grieve I was not

loos’d before;

She, I was loos’d at all.”

Fondness prevail’d, mamma

gave way;

Kitty, at heart’s desire,

Obtain’d the chariot for a

day,

And set the world on fire.

To this Horace Walpole, who

in later life took a kindly view of the duchess, added an extra verse:-

“To many a Kitty, Love his

car

Would for a day engage;

But Prior’s Kitty, ever

young,

Obtained it for an age.”

He describes her in 1773,

when she was an old woman, as looking “more blooming than the

Maccaronesses,” and says that by twilight she would be mistaken for a

young beauty of an old-fashioned century rather than an “antiquated

goddess of this age.” [Walpole’s Letters, vol. v. p.477.] He

was drinking her Grace’s health one day, and by way of a toast said that

he wished she might live to grow ugly. “I hope then,” she replied at once,

“that you will keep your taste for antiquities.” [Autobiography of Mrs.

Delaney.]

At the age of seventy the

duchess was still so young at heart that she was always to be seen

wherever there was a lighted candle, and would go ten miles to a party.

And to the end of her life she continued those eccentricities of dress and

conduct which rendered her such a conspicuous figure wherever she went.

Like old Lady Stair, the first person in Edinburgh to keep a black

servant, the duchess had a negro page-boy whom she taught to ride and

fence, and indeed spoilt in every conceivable way.

There is a picture of her

as a milkmaid by Jervas in the National Portrait Gallery in London, which

depicts her as a remarkably handsome woman, and though she contracted

smallpox in her youth, that then universal disease left no mark upon her

complexion. In her old age neither beauty nor high spirits forsook her. We

may get some idea of the clothes she was in the habit of wearing from a

description given by Mrs. Delaney. [Autobiography, ii. p.147.] In

this we read that the duchess’s dress was of “white satin embroidered, the

bottom of the petticoat brown hills covered with all sorts of

weeds” – (except, of course, widow’s weeds) – “and every breadth had

an old stump of a tree that ran up almost to the top of the petticoat,

… round which twined nastersians, ivy, honeysuckles, periwinkles,

convolvuluses and all sorts of twining flowers which spread and covered

the petticoat, vines with the leaves variegated as you have seen them by

the sun…” and so on. She must, in fact, have looked more like a cross

between a hothouse and a herbaceous border than a woman of fashion, and it

is not to be wondered at that her appearance formed the subject of general

comment.

The Duchess of Queensberry

had two children, neither of whom survived her. Henry, Earl of Drumlanrig,

her eldest son, was a soldier who served in two campaigns under the Earl

of Stair, and in another under Charles Emanuel, King of Sardinia, when he

particularly distinguished himself at the siege of Coni. In 1747 he

obtained a commission authorising him to raise a regiment of Highlanders

for service in Holland. His death was a tragic affair which affected his

mother profoundly. In 1754, a short time after his marriage, he was

travelling to Scotland in company with the duke and duchess and his

newly-wedded bride, when, owing to the accidental discharge of a pistol,

he shot himself, and succumbed almost immediately. His death was followed

two years later by that of his younger brother Charles.

The duchess lived till the

year 1777, when, if we are to believe Walpole, [Letters, vi. p.461.]

she died of a surfeit of cherries. He compares her death to that of the

old Countess of Desmond who “died of robbing a walnut tree,” and declares

that the duchess’s beauty at the age of seventy-seven was as extraordinary

as that of the countess at one hundred and forty. [Walpole declares

that at the coronation of George III. she still “looked well in her

milk-white locks,” and that “her affectation that day was to do

nothing preposterous.”]

The character of this

remarkable woman, who is said to have exercised a strong influence over

Pitt and the other statesmen of her day, cannot be better indicated than

by a quotation from one of her own letters.

“If any body has done me an

injury,” she says, “they have hurt themselves more than me. If they give

me an ill name (unless they have my help) I shall not deserve it. If fools

shun my company, it is because I am not like them; if people make me

angry, they only raise my spirits; and if they wish me ill, I will be well

and handsome, wise and happy, and everything, except a day younger than I

am, and that is a fancy I never yet saw becoming to man or woman, so it

cannot excite envy.” [Swift’s Works, xviii. P.70.] |