|

It was during the 17th

century that immigration from Scotland reached its zenith. The main reason

was naturally the many long wars in which Sweden was involved during the

first six decades of the century. Practically throughout this period there

was a need of both officers and enlisted men. The majority of Scots came

as military men, but there were others, too. It was in this period, for

instance, that commercial expansion in Scotland reached its peak, with a

resulting infiltration of Scottish merchants into Swedish cities. Their

interest in Sweden seems to have been the result partly of the country’s

new status as a great power, and partly of the exploitation of the

country’s natural resources that was the concomitant of that status.

Enlistment for the

Thirty Years’ War

A central figure behind the

enlistment of Scots for service in Sweden was Sir James Spens of Wormiston

(sometimes called Jakob Spens). He was born in 1571, in which year his

father took part in the capture of Lennox and forfeited his estates. His

father died while Spens was still a child, and his mother remarried, with

a member of the Anstruther family. In 1594 Spens became Provost of Crail,

in Fife. In 1598 he planned, together with his stepfather, to occupy and

colonise the island of Lewis, the largest and most northerly of the

Hebrides. The plan was discovered and Spens was imprisoned as a hostage.

In 1606 James Spens made

his entrance into Swedish history. In April of that year he received a

letter from Charles IX concerning the enlistment of 600 horsemen and 1600

foot soldiers. In January 1607 the King wrote that he hoped that Spens and

his troops would arrive with 8-10 ships in the spring. In 1608 pens

received a promise of the command over all British troops in Sweden, and a

colonelcy, provided that he arrived in the spring of 1609 with 500

horsemen and 1000 soldiers.

In June 1608 Charles IX

wrote to the Earl of Orkney, who had recommended his brother, William

Stuart, as enlisting agent. The King complained that no troops were

arriving, and that had he realised that William Stuart and James Spens

would not be able to keep their promises he would have sent over an

ambassador long since. He also wrote and complained to James VI, who

received in December 1608 a delegation consisting of James Spens and other

officers who were concerned to enlist men for service in Sweden. These

included Robert Kinnaird, who had been in contact with Charles IX as early

as in 1607, and two other Scots who became famous in Sweden, Samuel Cobron

and Patrick Ruthven.

Enlistment, however,

continued to move slowly. In February 1609 William Stuart received a

warrant to enlist 500 men, and Robert Sim, Colonel Rutherford’s adjutant,

200 men. When Stuart had not arrived by September Charles IX annulled the

order for two reasons, namely that the war was almost over and that the

summer was at an end. Stuart, however, arrived in January 1610 with 300

men. These 300 seem to have comprised the only Scottish contingent to have

arrived in Sweden during the first decade of the 17th century.

In 1611 Gustavus Adolphus

ascended the Swedish throne. War broke out with Denmark, which is reported

to have had 18,000 mercenaries in its service. In Sweden at that time

there was only one Scottish regiment, Colonel Rutherford’s (Captains

Learmonth, Wauchope and Greig).

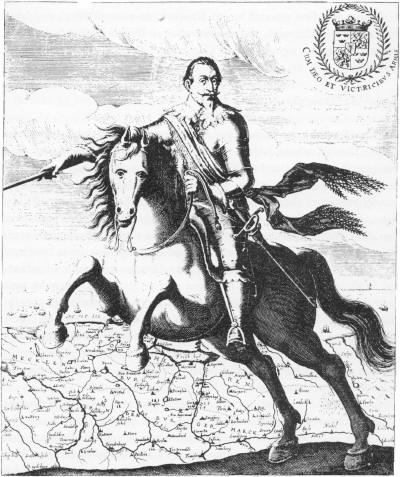

Gustavus Adolphus

Gustavus Adolphus appealed

to Spens in November 1611, speaking of the latter’s promises to Charles

IX, and requesting that he should as soon as possible bring 3000 men,

preferably infantry. With these he was to sail for Elfsborg in April 1612,

and money was to be provided in Hamburg. The King also mentioned

Münnichhofen’s enlistment of 1000 men in Holland, and suggested joint

transport. Münnichhofen succeeded in enlisting his men and the troops

landed in Norway, from which — ravaging the countryside as they went —

they made their way to Stockholm.

Spens himself played no

active part in the enlistment of the Scots. This job he left to Colonel

Andrew Ramsay, one of the favourites of James I (his brother John had

saved the King’s life in the Gowrie conspiracy.) One of the Earls of

Orkney, Robert Stuart, had plundered in Norway under the pretext of being

on the way to Sweden with troops. The Danish King, who was James’s

brother-in-law, protested violently against all this enlistement by

Sweden. In July-August 1612 James forbade that it should continue.

Captains Hay, Ker and

Sinclair were by then well under way with enlistments on behalf of Colonel

Andrew Ramsay. Their units, which do not seem to have been armed, had to

be disbanded, but a group of about 350 recruits, under the command of

Alexander Ramsay, Sinclair and others managed to leave from Caithness. On

19th August they arrived in two ships at Romsdalen in Norway, where they

disembarked and marched through Gudbrandsdalen to reach Sweden. On the

26th August they were attacked by Norwegian peasants in the pass of

Kringelen. All the Scots were killed except 134, who were taken prisoner.

On the following day 116 of the prisoners were killed, leaving 18 out of

the 350. Of these, Lt.Colonel Alexander Ramsay, his Lieutenant

James Mongepenny, who had previously been in Sweden and Denmark, and

Captain Henry Bruce, who had served in Holland, Spain and Hungary, were

sent to Copenhagen. Some of the remaining 15 were sent as recruits to a

Danish regiment at Elfsborg, and the others remained in Norway.

At the court martial in

Copenhagen it was found that Ramsay had embarked from Dundee, and G. Hay

and George Sinclair from Caithness. The latter had fallen in the fighting

at Kringelen. It emerged also that the soldiers had in no way molested the

population. The battle has long been regarded as a great feat of valour in

the history of Norway, and has repeatedly been used as a theme in

Norwegian literature and art.

Andrew Ramsay, who had led

the enlistment, was for this and for disobedience declared a rebel. He

proceeded to England, where he accused Sir Robert Carr (Ker, see above) of

Ancrom, Viscount Rochester, for having spread the rumour of the

enlistment. In England Andrew Ramsay was outlawed, but pardoned by 1614,

or possibly earlier.

Sir James Spens meanwhile

had visited Sweden in 1610, as Legate, and must then have met Gustavus

Adolphus for the first — but not the last — time. In the same year he was

made commander over all British troops in Swedish service, and was charged

to enlist 3000 men. In 1611 he was Swedish Legate in England, and in a

letter written to Gustavus Adolphus in the spring of that year he

recommends as captain one John Campbell, standard-bearer to Captain

Wauchope. Cambell, he wrote, was the most experienced of all Rutherford’s

officers in the training of recruits, and he had a good knowledge of

Gaelic. He recommended Andrew Ramsay for service in 1612, and Thomas

Hamilton in 1615.

In 1612 James gave Spens

the job of mediating between Sweden and Denmark, but in this Spens was

unsuccessful. In October of the same year, he became Swedish diplomatic

representative in Britain, and in December 1613 Swedish Ambassador. During

the following years he remained in London, writing on numerous matters to

Gustavus Adolphus.

James I sent him in 1619 as

British Ambassador to Sweden, and this was repeated in 1620. In 1622 he

seems to have been made a "baronet", but whether this was a British title

or a Swedish one we do not know. In 1623 he was sent as Swedish Ambassador

to London to acquire permission to enlist troops for the war against

Poland. His son, James, received permission to enlist 1200 Scots, and in

the same year Sir James returned to Sweden as British Ambassador to bring

about an alliance between Britain, France and Sweden. He returned to

England in 1624, but the claims made by Gustavus Adolphus were thought too

high, and it was instead Denmark that was included in the alliance. In the

same year Sir James visited Holland as British Ambassador.

During the period 1624-29

Spens lived mainly in London. In 1626 he was appointed Court Counsellor

and Swedish Legate in Britain. In 1627 he travelled as Britain Ambassador

to Danzig and Brandenburg, during which journey he also presented the

Order of the Garter to Gustavus Adolphus. This was shortly after the

famous battle of Dirschau, in which the King had been badly wounded, and

during the ceremony the outposts of the camp were attacked by the enemy.

In 1628 Spens was created Baron of Orreholmen (in Vastergotland) and in

the following year he once more became regular Swedish resident at

Charles’ court.

The last two letters from

Gustavus Adolphus reached him in 1629. The first informed him that the

Earl of Crawford wished to raise a couple of regiments for service in

Sweden, and the second, dated in May, ordered Spens to take in person and

as soon as possible the newly acquired troops over to Germany. After this

James Spens seems to have accompanied the King in Germany. In 1632,

however, he was in Stockholm, where he died shortly after learning of the

King’s death at Lutzen —according to tradition from the shock he felt at

the news.

He was buried in Stockholm,

in Riddarholmskyrkan, the burial church of the Kings of Sweden.

His son, James Spens,

probably the eldest son from his first marriage (with Agnes Dune), who was

to enlist 1200 men in Scotland in 1623, is in all probability the Colonel

of a regiment which appears in the Swedish rolls. Another son in Sir

James’ first marriage, William Spens, Lt. Col., died in 1647. Three

daughters from his first marriage were married to Scottish officers in

Swedish service: Cecilia to Major-general David Drummond (1589—1638),

Isabella to Major-general James Ramsay (1589-1638), and a third daughter,

to Captain William Monipenny. In his second marriage, to Margareta Forath,

there were two sons: Axel Spens (1626-1656), Major, father of Jakob Spens

(1656-1721), Major general and Count (who founded the present Swedish

line) Jakob Spens (1627-1663 or 1668), Colonel and unmarried.

Samuel Cobron

Samuel Cobron (Cockburn),

who was probably born around 1574, appears in Swedish service in 1606-07

when he took part in the fighting in Livonia, as Captain of a newly

enlisted troop of foot soldiers. At the turn of the year 1608-09 he

travelled with Sir James Spens and other Scottish officers to England, to

enlist further men. By the same autumn he was back in command of a new

troop of horse, which in i6io took part in Colonel Evert Horn’s expedition

in Russia, in which there shortly broke out a mutiny under the leadership

of two British officers. The mutiny was quelled and Cobron was put in

command of the entire British contingent and joined de la Gardie’s and the

Swedish army was taken by surprise by the Poles at Clusina. The Polish

Army was overwhelmingly superior in numbers, and the Russian allies fled

immediately. A new mutiny broke out, and de la Gardie was forced to

capitulate in return for a free passage for Horn, himself, and all men who

wished to remain loyal to Sweden. Cobron was one of the few non-Swedish

officers who returned to Sweden.

In the autumn of 1610 he

was in command of an enlisted regiment that consisted of seven troops of

foot soldiers and two troops of horse. This regiment took part in the

storming of Novgorod, 16th July 1611. He commanded one wing of the

attacking force, and was one of the first to enter the city. His regiment

lay in quarters in Abo during the winter 1612-13 and then took part in an

unsuccessful expedition in Russia. In 1614 he was in command of 2000 men

and succeeded together with Colonel Münnichofen in blockading a large

Russian force, thus securing Swedish possession of Novgorod. Later this

year he took part in the taking of Gdow, and was made Major-general. In

the following year he first cleaned up the Ladoga district and was later

in command of all English, French and Scottish troops before Pskow. His

regiment was by now unfit for service, and was discharged in 1616. When

the war with Russia came to an end, and with the approval of Gustavus

Adolphus Cobron negotiated 1616-18 to enter Russian service against

Poland. His plans, however, did not materialize and 1616-21 Cobron seems

to have lived as a country gentleman on his Finnish estate.

In 1621 he took fighting

men from Finland to Livonia, and during the summer he was with the Royal

Army before Riga, in command of the forts on the islands in the Düna and

on its south bank. One of these forts came to bear his name for more than

a century. He was here wounded in the leg by an exploding cannon, but by

November he was active once more and commanded the advance troop of

cavalry in the expedition against Kokenhausen. He died of camp-fever

during December 1621.

He was buried in 1622 in

Abo Minster under a magnificent monument erected by his "frater", M. Johan

Klaparton, who started a law suit through an agent to claims his estate.

On the monument there can be read: "You lived bravely, but died cruelly.

Mars and Minerva rest with you in the same grave. Never have Sweden and

Scotland had more sorrowful — or Poland more welcome — (news)."

Cobron was first married to

one Kristina (mentioned 1614) and later to Barbro, née Kinnaird, widow

since 1606 of Willem Ogilvie, a Swedish colonel. He never signed himself

Cockburn.

Jacob Mac Dougall

Another Scot of great

importance at the beginning of the 17th century was Jakob Duwall, whose

father, Albert MacDougall of Mackerstone, had emigrated from Scotland to

Mecklenburg and moved many years later in c. 1600, to Sweden, where he

became a bailliff. He died, probably nearly 100 years old, in 1641, by

which time he had outlived 7 of his 9 sons, all of whom were officers in

Swedish service. Jakob Duwall was born in 1589 and took service as a

musketeer in 1607. He became Captain in 1641, Lt. Colonel in 1621, and

Colonel of a regiment from Norrland in 1625. In 1629 he had enlisted two

German regiments of infantry. In the autumn of 1628 he had been sent to

Stralsund, where he took part in the mopping-up operations preparatory to

the Swedish landing in 1630. In 1631 he was made Commendant of

Frankfurt an der Oder after the capture of the city, and in the following

year "General Commendeur" of a Swedish army in Silesia. He seems to have

been partly responsible for the defeat at Mitau in 1633, when

Wallenstein took the Swedes by surprise. He died in 1634 and is buried in

Stralsund.

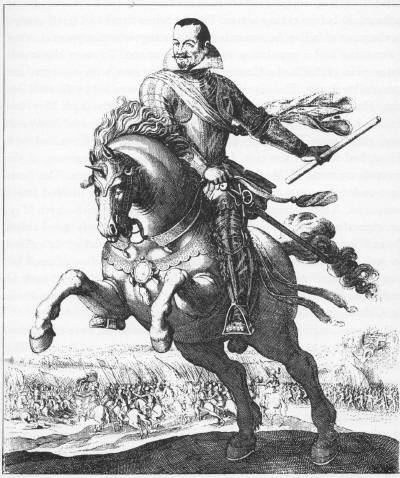

Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland

Jakob Duwall had two sons,

Jakob Duwall (1625-84), who became County Governor of Osterbotten, and

Gustaf Duwall (1630-92) who was born in Stralsund, and became an extremely

skilful diplomat and administrator. In 1662 he became County Governor at

Dalecarlia. In a series of Riksdags he was the Speaker of the non-titled

nobility and his career was crowned in 1674, when his father, 40 years

after his death, was created baron, and in 1675, when he himself, as Lord

Chancellor, led the Swedish nobility in an important Riksdag.

James Hamilton’s

Expedition

From the British point of

view the political situation of the early 17th century was in short as

follows.

James VI was a peaceful

monarch in a turbulent age and always unwilling to enter a war. He was

regularly short of funds.

In 1611 he betrothed his

daughter Elisabeth to Frederick of the Palatinate. In the previous year

Charles IX had initiated a proposal to her on behalf of Gustavus Adolphus,

and James had at first approved. The earlier proposal, however, had failed

owing to the opposition of the Queen, who was born Princess of Denmark, as

her native country was at that time at war with Sweden.

Frederick was elected King

of Bohemia in 1619, and James found, to his sorrow, that he had become to

some extent involved in the Thirty Years’ War, as the energetic and clever

Elisabeth was an indefatigable champion of her husband’s restitution.

Although Charles I had a great weakness for his sister, he had neither the

money nor the interest to enter the war.

The longer the Thirty

Years’ War dragged on the harder Gustavus Adolphus worked to gain Britain

as an ally. Charles I, however, drew closer and closer to Denmark.

Elisabeth did all she could to bring about an agreement, and it was she

who arranged an Order of the Garter for Gustavus Adolphus who was the

first Swede to receive this honour. It was presented to him by Sir James

Spens at Dirschau in 1627. This was, however, a poor substitute for an

alliance, as Sweden was very hard pressed at this time. Gustavus Adolphus

now began to associate himself with the Earl of Buckingham, with whom he

signed a treaty in 1628. After the murder of the latter shortly

afterwards, Sir James Spens was once more sent to London to persuade

Charles. Spens arrived in March 1629, but although the atmosphere was very

friendly Charles could not be brought to make any promises.

In this situation Spens

came into contact with Hamilton, who provided an opportunity for Charles I

to help without entering the war.

Hamilton, 2nd Marquis of

Hamilton, was married to Anna Cunningham, a woman of strong will. He was a

country nobleman who joined the court of King James in London in 1615, and

had high titles bestowed on him. His son, James Hamilton, 3rd Marquis and

1st Duke of Hamilton, was born at Hamilton Castle in 1606.

From there he was brought —

at the age of 14— to London for a political marriage with a seven year old

daughter of the Duke of Buckingham. He stayed in London for five years and

seems to have found no friend except Charles, later Charles I. He watched

his father grow further and further apart from Buckingham, and finally

die, poisoned it was said, by the latter. Almost simultaneously King James

died and in 1626 Charles I was crowned. Young James Hamilton carried the

Sword in the procession, after which he left court and returned home to

Hamilton Castle. Not until Buckingham had been murdered in 1628 did he

accept the offer of a high position at court, and return.

Once in London he was

immediately drawn into politics, above all by the King’s sister Elisabeth,

wife to Frederick of the Palatinate. She planned at this time to have a

British army of volunteers liberate the Palatinate together with the

troops of Gustavus Adolphus, and she saw in James Hamilton a suitable

commander for the enterprise. Hamilton, who was by now 22, was attracted

by the idea. He can also have been influenced by the famous diplomate

Thomas Roe, who in 1629 had been British legate to Gustavus Adolphus.

Further persuasion was naturally brought to bear by Sir James Spens, then

Sweden’s envoy in London, with whom he came into contact in the spring of

1629.

Later on in the summer of

1629, Hamilton and Spens discussed an expeditionary corps to be called the

"English Army", and a few months later Hamilton began to negotiate terms

with Gustavus Adolphus. As intermediary he used his kinsman Archibald

Hamilton, a Colonel in Swedish service who arrived in Sweden in October

for secret consultation with the King, and in December Gustavus Adolphus

wrote a very positive letter to Hamilton.

In the winter 1629-30

Colonel Hamilton met in Stockholm Lord Reay, Master of Clan Mackay, and in

command of the regiment of this name. Robert Monro was also in Stockholm

at this time. In March 13 Scottish officers dined with the King. Lord Reay

tried, without result, to pump Colonel Hamilton on what was actually

happening. With David Ramsay who arrived in 1630 to conclude negotiations

Lord Reay met with more success. In the summer of 1630 Lord Reay returned

to London. Negotiations did not end until 31st March 1631, by which time

Hamilton had had to renounce much of the freedom of action he had demanded

in the beginning.

In 1630 Hamilton enlisted

men, mainly in Scotland but also in England. From August to October of

that year there served as military expert with Hamilton an unknown

adventurer named Wolmar Farensbach who had been specially appointed by

Gustavus Adolphus, but in the autumn he defected to the Emperor. In his

place the King sent Alexander Leslie, who did not, however, arrive in

London before 12th June 1631. At the end of June the expeditionary corps

of four infantry regiments of all together 5000 men, plus the Marquis’s

lifeguard mustered in Yarmouth to embark. Forty ships had been assembled

for the voyage. Preparatory to his departure Hamilton was honoured with

the Order of the Garter.

It was then that Hamilton

was denounced by a certain Lord Ochiltree, who claimed to have evidence

that he intended to land in Scotland and proclaim himself king. The

background to this charge was that Lord Reay had offered his services to

Hamilton but had been refused, and in anger had "embroidered" in speaking

to Ochiltree what he had heard in Stockholm from David Ramsay in the

spring of 1630. Lord Ochiltree was an old enemy of the Hamilton family.

Hamilton was recalled to London, where he demanded redress. Ochiltree,

Reay and David Ramsay were imprisoned in the Tower, and a court was

appointed. The witnesses included Colonel Alexander Forbes, the chief of

the Forbes Clan, who was called home from Germany exclusively for this

purpose. Reay demanded a duel with Ramsay, but both were acquitted.

On the 16th July 1631 the

fleet could sail and anchored on the 27th in Elsinore where Hamilton

called on the Danish King at Frederiksborg. July 29-31 they sailed to the

mouth of the Oder, between Wolgast and Usedom, to disembark 2nd-3rd

August. Almost immediately, however, there broke out a pestilential

disease, and within six weeks the deaths had amounted to one third of the

force, i. e. 2000 men.

Gustavus Adolphus was

delighted at Hamilton’s arrival. He had already for some weeks been

exploiting the "English Army" in his propaganda, and the effect was

heightened by its actual landing. The result was that Tilly gave up

blockading the Swedes in their permanent camp at Werben and went over to

the defensive. On the 10th August Hamilton visited the Swedish King in

Werben with due pomp and state. Hamilton who was untried as a soldier, was

excluded from the Swedish High Command, and his army was given the rather

modest task of operating behind the Swedish army.

In September, Hamilton’s

army, which was by now down to just over 1000 men, was reinforced by 2000

men from Swedish units, and was transferred to Johan Banér’s Army Corps.

He and Hamilton never managed to get on together. This must have been due,

in part at least, to the fact that they had to converse always through an

interpreter.

By February 1632 the

"English Army" had dwindled, in spite of reinforcement, to 700 men and

Hamilton suggested that they be combined with other units. He himself set

out to meet Gustavus Adolphus in Frankfurt am-Main.

His object was two-fold, to

persuade the King to set up a new army for him, and to support the current

British negotiations. He seems to have accompanied the King from Frankfurt

via Augusburg to Munich, where he once more had occasion to meet his

patron, Queen Elisabeth. The negotiations reached a deadlock, however, and

the King showed no interest in the new army. Hamilton stayed the summer in

Germany, but then gave up, and in August he obtained the permission of

Charles I to return. At the beginning of September he called for a last

time on Gustavus Adolphus in Fürth, together with Colonels John Hepburn

and James Hamilton, after which he departed from the theatre of war.

Scottish Troops at

Stralsund, 1628

The Northern German Baltic

city of Stralsund, south of the island of Rugen, was the bridgehead that

made it possible for Sweden to intervene in the Thirty Years’ War. The

Emperor’s general, Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland, had in 1627-28

succeeded in gaining control over practically all the more important

German cities on the Baltic, with the exception of Stralsund. He had begun

rapidly to build naval bases to secure control also over the Baltic

itself, and the Protestants were hard pressed. Christian IV of Denmark —

brother-in-law of James VI of Scotland — made an unsuccessful attempt to

slow down the advance of Wallenstein. Gustavus Adolphus, engaged as he was

in his war in Poland, delayed as long as he could before taking action.

Finally, when Stralsund itself seemed on the point of falling, he

succeeded in liberating units to support the city.

Stralsund had a population

approaching 20,000. To meet the expected siege in 1628 it had a Citizen

Army of 2500 men, a levy of 1500, and 1000 enlisted men. The siege began

in May and was led by General Arnim. The first attempt to take the city

was made 16th-24th May, but the inhabitants defended themselves

bravely, and the Imperial Army suffered great losses. By as early as 8th

May a Danish expedition had been dispatched to assist the city. It arrived

on the 24th, consisting of the Scottish regiment of Mackey, and a company

of Germans. The Scots were under the command of Alexander Seaton and were

divided into 7 companies. A fresh attempt to storm the city was made 26th-27th

May, but thereafter until the arrival of Wallenstein it was only

bombarded. On 2nd June a Swedish auxiliary expedition was dispatched. It

arrived on 20th June, and was set ashore after the conclusion of an

alliance between Stralsund and Sweden. It consisted of 600 men from

Norrland under the command of Colonel Rosladin. His second in command was

Lt. Colonel Axel Duwall.

Wallenstein arrived on 27th

June and took command over the besieging force. That same night a new

attempt was made on the city. The main attack was launched on the

Frankenport, where Monro was in command. The fighting was fierce and

bloody, and the Scots lost 2000 men fallen and taken prisoner. Monro was

wounded and Axel Duwall captured. The city’s main positions, however, were

retaken by a skilful counter-attack under Rosladin. On the following night

Rosladin was badly wounded, and this sector was transferred to the command

of Seaton, who was forced to evacuate the outer works. By the 30th June

the city was concerned to start negotiating with Wallenstein, but this was

prevented by the firm attitude of Rosladin. No further attempt was made to

storm the city, and during the bombardment that followed the city’s forces

were gradually reinforced. On 2nd July 400 Danes arrived, and a week later

the Scottish regiment of Mac Spynie (in Danish service), 1100 men strong.

A further week saw the arrival of Alexander Leslie from Sweden with 800

men from Norrland. Leslie took command in the city, and 21st-24th July,

after the autumn rains had begun and turned the area around to a marsh,

Wallenstein was forced to break off the siege.

The relief of Stralsund was

of decisive importance. The Imperial troops had shot their bolt for a

while. The pressure of the attack eased off, and Gustavus Adolphus was

enabled to devote his full attention to the Gerwan theatre of war. By 1630

he had been able to regroup his forces, and landed on Usedom, which was

the springboard for his German campaign.

James King

James King (Sir James King

of Birness and Dudwick, later Lord Eythin) was born on Orkney in 1589, and

was the son of David King of Warbester Hoy. He entered Swedish service in

1615, and in 1622 was made a Captain in Ruthven’s regiment. In 1632 he was

made Colonel and two years later Major-general. At Wittstock, in 1636, he

commanded the left wing, and in the following year he was made Lt. General

and Governor of Vlotho on the Weser, where he was defeated by Hatzfeld. He

had great difficulty in subordinating himself to General Banér, the

Swedish Supreme Commander, and was for this reason in 1639 called to

Stockholm, where he was raised to the nobility. He returned the same year

to England, where he was well received by Charles I, who used him both to

enlist men on the continent and as general. King was thus in command of

the centre at Marston Moor. He was created Lord Eythin in 1642, and in

Sweden became Baron of Sanshult. In March 1650 he was to have taken part

as Lt.General in Montrose’s expedition, but did not succeed in enlisting

any men. He died in 1652 in Stockholm, and was given a state funeral.

HIS JACET NOBILISSIMUS AC

GENEROISISSIMUS DOMINUS D.KING LIB. BARO DE EIJTEN IN REGNO SCOTHISA

DOMINUS INFONSH HULT ET EQUES AURATUS NEC NON SERENISSIMAE

POTENTISSIMAEQUE REGINAE REGNIQUE SVETHIAE QUONDAM GENERALIS SEPULTUS 1652

D. 18 JULII Around the stone, MILITIA EST VTA HOMINIS SUPER TERRAM— VIVIT

POST FUNERA VIRTUS

James King seems to have

had several relatives in Swedish service. One Thomas King had pay due as

an officer in 1595. The General’s eldest brother, John King of Warbester

was a Swedish officer and had two sons, both Swedish officers, James, the

principal heir of his uncle, and Henry. Another brother, Major David King,

distinguished himself at Donauwört in 1632 and fell at Nordlingen in 1634.

Members of the main line of the family, King of Barra, also appear in

Sweden during the second half of the 17th century. It appears from the

General’s will that he had a half brother, William Sinclair of Seaby,

whose son, David Sinclair, was a Lt.Colonel in Swedish service.

Patrick Ruthven

Patrick Ruthven, later Lord

of Ettrich and Earl of Forth and Brentford (1586-1651) first appears on

the stage of Swedish history when he took part in Spens’ delegation to

James VI in December 1608. He later took part in Charles IX’s campaign in

Livonia. He was Captain of Horse during Evert Horn’s Russian campaign of

1612, was made Major in 1613, and took part in the fighting around

Novgorod 1613-14.

In the latter year he

travelled home to Scotland to enlist troops, and returned in 1615 with 500

men, who were quartered in Narva. In 1615 he became Quartermaster General,

and in 1616 was in command of the fort at Pleskow. In 1617 he was once

more in Novgorod. He took part in Gustavus Adolphus’ Livonian campaign of

1623, and in 1623 became Colonel of the Kalmar Regiment. In the years

immediately following he reorganised this regiment, consisting entirely of

Swedish troops, and fortified the city of Kalmar.

He took part in Gustavus

Adolphus’ Prussian campaign in 1626, distinguished himself at Mewe, and

was knighted in 1627. In the same year his regiment, by now in sad shape,

was discharged, while he himself remained and supervised in 1628 the

fortifying of the Weichsel Line. In 1629 he was given the command of an

enlisted regiment of Scottish infantry, which was first stationed in

Elbing, but was transferred to Memel in 1630.

He served in the German

campaign of 1631, and in the following year was made Major-general and

Commendant of Ulm, the fortifications of which he strengthened. In October

1631 he was made second-in-command of the entire army in Swabia. In 1634

he travelled once more to Scotland to enlist men, and on his return was

transferred to Banér’s Army Corps, where he commanded an enlisted regiment

of cavalry. In 1635, at Dömitz, he won a brilliant victory over a Saxon

force under Baudissin.

In the following year he

was once more in Scotland to enlist men, and received an offer of a

command in his home country. He left Swedish service in 1637.

To his brothers-in-arms

Patrick Ruthven was known as Pater Rotwein; it was not only that they

found his name difficult to pronounce, he was also famous in the army for

his prowess as a drinker. In fact Gustavus Adolphus often appointed him

host at the banquets held at headquarters.

Entering British service,

he was given the command of the royal troops in Scotland. In 1639 when the

Civil War broke out he was Commandant of Edinburgh Castle and was besieged

by the rebels and forced to capitulate in September 1640. In 1646 he

accompanied the House of Stuart into exile.

He later wrote to the

Swedish Crown concerning the pension granted him in 1638, and made a visit

to Sweden on the same matter. In 1650 he landed with Charles II in

Scotland, and died shortly afterwards.

His first marriage was to a

daughter of Alexander Leslie. |