|

The first occasion on which

we learn of Scottish troops in Sweden is in 1502, but they were in Danish

service. A large contingent arrived that year in Copenhagen and were later

employed in the fighting against Sweden. In 1520 a number of Scots took

part in Christian II’s expedition against Sweden and in the capture of

Stockholm.

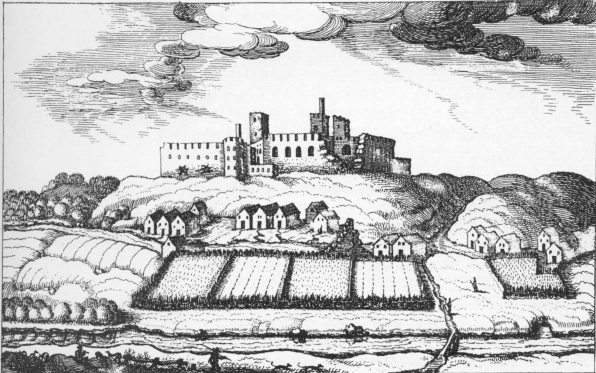

Detail of Hogenberg's engraving of Stockholm

around 1580. Seen from north.

In the following year

Gustaf Vasa, assisted by Lubeck, liberated Sweden from the Danish King,

known in Sweden as Christian the Tyrant. King Gustaf generally turned to

Germany whenever he needed to enlist troops, but occasional Scottish units

may have been included. In 1556 there were negotiations between Gustavus

Vasa and one Johannes Edmonstone on the raizing of troops in Scotland, but

they do not seem to have come to anything.

Under Gustaf Vasa’s three

sons the situation changed. The father had with great vigour tried to

transform mediaeval Sweden into a modern state, but to keep it rather

isolated from the rest of Europe. The sons, each of whom ruled Sweden in

turn, devoted great attention to foreign policy. In the spirit of the

time, political marriages were sought as one of the most important means

of furthering that policy.

For almost five years from

1557 the eldest son Eric courted Elizabeth. Three times he sent

ambassadors to her court, on one occasion his brother, Duke John. He was

about to set sail for England in person in 1560 when Gustaf Vasa died.

From 1561 King Eric XIV courted also Mary Queen of Scots, whose suitors

later included his brother Magnus. Although none of these attempts led to

any result, nevertheless they had their importance, in that the envoys

sent out also tried to enlist troops and to promote trade.

The castle of Wesenberg in Livonia

In

1563 Eric XIV wrote to an agent in Scotland and requested the enlistment

of 2000 men. In this year the Scandinavian Seven Years’ War broke out

between Sweden and Denmark. No mention is found of any Scottish infantry

on Sweden’s side during this war, and it is uncertain whether the King’s

letter had any result. On the other hand, a troop of Scottish cavalry

appears as early as in 1565, and five years later there were at least

three troops, under Willem Cahun, Robert Crichton and Andrew Keith. In

1568 Eric XIV was deposed and imprisoned, and the throne occupied by his

brother John III. After bringing the war to an end in 1570, John was

concerned to discharge his foreign cavalry, which by then numbered seven

troops (3 Scottish, 1 English and 3 German) but in the case of the

Scottish troops at least this seems to have been a long drawn-out

procedure.

Meanwhile, relations with

Russia became strained, and in 1573 foot soldiers were enlisted in

Scotland on a large scale. In June of that year there arrived a large

contingent, perhaps as many as 4000 men. This troop, which was under the

command of Colonel Archibald Ruthven, marched through Sweden to be shipped

out to the fighting in Esthonia and Livonia. The Scottish cavalry from the

Seven Years’ War seem then still to have been in Swedish service.

In 1579 we learn of Jakob

Neaf as a Captain of Horse, but it is not known if his men were from

Scotland. In the same year the name of Henrik Leyell also begins to appear

as Captain of Horse, and ten years later, at all events, his troop

consisted of Scots.

In 1591, when the situation

at the Russian border hardened, there were two troops of Scottish cavalry

in the Swedish army, Henrik Leyell’s and a new troop under the command of

Willem Ruthven. The latter’s patent for the enlistment of horsemen is

still preserved, and it is clear from this that he had the right to enlist

Scottish horsemen wherever he could find them, although it is hardly

probable that he did in fact enlist his men in Scotland. In 1593 a further

troop of cavalry was enlisted by Abraham Young. Henrik Leyell’s troop was

still in service in 1597.

John III died in 1592 and

was succeeded by his son Sigismund, but as the latter was King of Poland

and a Catholic, Sweden came to be ruled by John III’s brother Duke

Charles, who became king at the turn of the century as Charles IX.

Professional soldiers were needed for the War of Succession that then

broke out between Sweden and Poland. Charles IX wrote numerous letters to

different people in Scotland in an attempt to get men enlisted, but

apparently without result until 1607.

Archibald Ruthven

Archibald Ruthven was son

of Patrick Ruthven, 3rd Lord Ruthven, and Janet Douglas, daughter of the

Earl of Angus. His father had instigated the murder of Cardinal Riccio in

1566 and died in exile in the same year. Archibald was the fourth son, the

eldest died and another was murdered in 1571. His brother William Ruthven,

4th Lord Ruthven, had also taken part in the murder of Riccio, but

returned to Scotland. He was Lord Treasurer from 1571. In 1581 he was

created Earl of Gowrie. The statement, sometimes to be found, that he

visited Sweden is probably false.

Archibald signed himself

"of Forteviot and Master of Ruthven". In 1572 he was recommended to John

III by the Regent, Mar. In the autumn of 1572 he stayed at John’s court in

Vadstena for five weeks with an escort of eleven men and three extra

horses. He was commissioned on this occasion to go over to Scotland to

enlist 2000 men. He travelled via Denmark where he met Dancay in March.

The latter wrote (2nd June) to Catherine of Medici: "In Denmark all is

calm, not so in Sweden. Those who come from that country have strange

tales to tell. About four months ago there came a Scottish nobleman,

Master Rewen, brother to My Lord Rewen, passing through Denmark on his

journey from Sweden to Scotland to enlist soldiers for the King of Sweden.

I have now heard from those coming from Scotland that he has enlisted a

number of men which he hopes soon to take over to Sweden." At the written

request of, among others, the King’s Court Commissioner, Anders Keith,

enlistment was made on a larger scale than had originally been planned,

and the total number enlisted was in the end probably around 4000 men.

The troops enlisted were of

the Reformed Church and many of them had just taken part in the siege of

Edinburgh Castle. Archibald Ruthven himself took part in this siege which

led to the capture of the castle on 28th May. According to a letter from

the Earl of Morton to John III, dated June 19th, he was then still in

Scotland but arrived in Elfsborg in Sweden already on the 18th and was

immediately ordered to proceed to the King.

Later on in the summer

Archibald Ruthven arrived in Stockholm with his force, and a number of

complications immediately arose. The direct cause of the trouble appears

to have been that the pay of the Scottish troop was missing. The Scottish

officers were accused of having embezzled the same, and in a tight corner

they made the accusation a question of honour. They held a countryman,

Hugh Cahun, who had been five years in the service of John III,

responsible for the accusation, and refused to sail to the fighting in

Livonia until he had been executed. The King gave way, and Hugh Cahun’s

head fell in the Great Square in Stockholm. The Scots then set sail. This

situation reflects the terror felt by the Swedish authorities for the

numerous foreign soldiery. John III’s bad conscience was eased by a

generous pension to Cahun’s widow.

In the late winter of 1574

the main Swedish force was camped outside the Russian fortress of

Wesenberg in Livonia. Pontus de la Gardie was in command and tried three

times to storm the town, suffering great losses. The besieging force

included Swedish and Scottish foot soldiers and Swedish and German

cavalry. There was much ill-feeling between the Scottish infantry and the

German cavalry and on the 15th March fighting broke out between them.

German cavalry attacked Scottish soldiers and Colonel Ruthven, who tried

with De la Gardie and other officers to intervene, was badly wounded. One

of the troops of Scottish cavalry (Wilhelm Moncrieff’s) joined in on the

side of their countrymen and several hundreds (some sources give 1500)

were killed. A number of Scots fled to the besieged Russians in Wesenberg.

At the trial that was held in Stockholm the Scots — probably unjustly —

were given the chief blame for what had happened. The Scottish force had

been broken. Ruthven, who had been wounded, and Gilbert Balfour were sent

in irons to Stockholm. There, cut off from the remainder of their forces,

they were accused of having played a leading role in Charles de Mornay’s

conspiracy to replace Eric XIV on the throne. For six years Eric XIV had

been kept imprisoned by his brother and successor, and the risk of his

being liberated by his followers had been a continual and predominant

problem for John III. Twice during the previous autumn, apparently,

Archibald Ruthven and Gilbert Balfour — experienced in such matters since

the murder of Lord Darnley — had plotted the murder of the King, under the

supervision of Charles de Mornay. On the first occasion certain Scottish

captains were to rush to the King’s bedchamber and the minutes of the

trial inform us that he was saved only by chance. On the second occasion

it was planned that the murder should take place in grand style at the

farewell banquet that was held at Stockholm Castle, after payment had

finally been made and the departure of the Scottish force to Livonia

agreed. A Scottish sword dance was a natural feature of the festivities

and gave the conspirators their chance to bare weapons. The murder was to

be the climax of the dance — but de Mornay’s nerve failed him at the

decisive moment and he never gave the agreed sign.

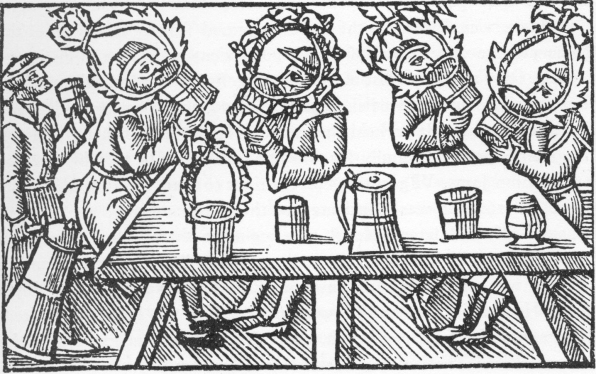

Sword dance. "Historia de gentibus

septentrionalibus" by Olaus Magnus 1555.

It is impossible to

distinguish facts from false accusation in this story. What is certain is

that Charles de Mornay was led to the block in Stockholm in September

1574. "Today" he is reputed to have said, "dies Carolus, by whose good

service King John is alive." It is also a fact that Archibald Ruthven died

imprisoned in Vasteras Castle, in February 1578, after a number of

petitions from prominent countrymen in Scotland had been ignored. Gilbert

Balfour was condemned to death in the autumn of 1574 but long succeeded in

avoiding execution by claiming knowledge of the legendary treasure of Eric

XIV. After belief in this story had waned, following repeated

interrogations, Balfour gained a further respite by an offer of 800 golden

nobles. The King raised the demand to around 1000, and when the prisoner

was unable to raise this amount, the axe fell in August 1576.

Jacob Neaf

Jacob Neaf’s origins are

obscure, but he was a Scot and appears in Sweden for the first time in

1571, when he was page to John III. Two years later he was a private

soldier (possibly Ensign) in Andrew Keith’s troop. Sometime before 1575 he

married the daughter of a well-to-do Stockholm merchant. In 1579 he was

Captain of Horse, and from 1583 Governor of Västmanland and Dalecarlia. In

the middle of the 1580’s he received as a gift Marby, on Oknön in Lake

Mälar, and this he made his family seat. He was a Roman Catholic, and a

warm adherent of King Sigismund, which made him highly impopular with the

Dalecarlians. In 1596 an attempt was made on his life in Dalecarlia, and

in 1598 when he attempted to proclaim the banishment of Duke Charles, he

was imprisoned, manhandled and killed.

He had a son, Johan Neaf,

who was murdered in Stockholm, 1607, on his return from Poland and King

Sigismund. One of Jacob Neaf’s daughters married Johan Skytte, Gustavus

Adolphus’ tutor, who in 1634 placed a stone on his father-in-law’s tomb in

Stora Tuna Church.

The stone was adorned with

eight somewhat imaginative coats-of-arms, and an inscription that roughly

translated would run: "Jacob Neaf, a noble Scot/ Of Noble line and birth/

In Dalecarlia lived, where ‘twas his lot/ To govern, while on earth./ On

Oknö lay his temp’ral home/ A gift from the King of Sweden./ Hereunder

rests he now his bones/ And waits a Heavenly Eden." The shields are

thought to be those of: Neff, Baron of Methie/ Lord de Gray/ Leslie, Earl

of Tothes/ Lindsay, Earl of Crawford/ Wishart, Baron of Pitarro/ D.

Lindsay/ Lord Ogilvie/ Ramsay, Lord of Auchterhouse.

Andreas Keith, Lord

Dingwall, Baron of Forsholm and Finsta

It is not known when or

where Andrew Keith was born. He was the illegitimate son of a man of the

church, Robert Keith. The mother’s name is unknown but his father, who was

Commendator of the Abbey of Deer, died in Paris in 1551, and lies buried

in front of St. Ninian’s altar in the Carmelite Church in the Place

Maubert. Andrew Keith was of high birth, his uncle being William Keith, 4th

Earl Marshal. Andrew Keith entered Swedish service in 1568 and from

1568-73 was captain of a troop of Scottish horse. In 1574 he became

Commandant of Vadstena Castle and was created Baron. In 1576 he became

Court Commissioner.

In the early 1570’s,

probably in 1573, he married a Swedish lady of high birth, Elisabeth

Birgersdotter Grip. She was related to John III (her grandmother was

Gustav Vasa’s sister) and the King seems to have paid for the wedding. In

1578 Keith bought a house in Stockholm, and in 1580 we learn on two

occasions of a builder in his employ, so that we can assume that it was on

this occasion that he built the house that still exists in Baggensgatan.

It has a stone plaque with the arms of Keith and his wife, their names and

AUXILIUM NOSTRUM A DOMINO.

In 1583 Keith was Swedish

legate to Queen Elizabeth of England. A letter from James VI of Scotland

to John III is still preserved, in which Keith seems to have been released

from his service to Sweden. He was created Lord Dingwall in 1584, and was

appointed as one of the ambassadors who were to arrange the marriage that

took place in 1590 between James VI and Princess Anne of Denmark. For this

purpose Andrew Keith journeyed six times between Scotland and Denmark and

for his services he received a life annuity of £1000 from 1588/89 and, in

1591, a confirmation of his title of Lord, and soon afterwards he seems to

have left Scotland for good. In 1589 he was a member of the court that

tried the Earl of Bothwell for treason, but by as early as 1592/93 Sir

William Keith of Delny held the deeds of all the possessions he had in

Britain. The title, however, did not follow with the estate, and Sir

William never signed himself Lord Dingwall.

Keith had the whole time

maintained his links with Sweden and the House of Vasa. In 1587 he had

been appointed Court Counsellor by Sigismund, John III’s son, who was

elected King of Poland that same year, and in the following year he had

paid a short visit to Sweden. During the 1590’s Andrew Keith seems to have

been a warm supporter of King Sigismund, and he was exiled from Sweden by

Duke Charles, who was then in power. The last we hear of Andrew Keith is

that in 1597 he wrote his wife a letter from Elsinor. In all probability

he died before 1600 as his wife then signed herself "of Finsta", the

Swedish estate he had used in his signature during the 1590’s. He had no

children, but in 1609 a claim was put forward in Stockholm to his estate

by a Scottish envoy who also bore the name Andrew Keith.

Hans Stuart

The first Stuarts in Sweden

were two sons to Johannes Stuart of Ochiltree, who accompanied Mary Queen

of Scots to France in 1558, and who served as Colonel under Francis II of

France until the latter’s death in 1560, when he returned to Scotland. His

wife’s maiden name was Forbus. His son, Hans Stuart, was in 1565 captured

by the Danes on a voyage from Edinburgh to Danzig and taken to Varberg

where he was held prisoner, it being suspected that he intended to enter

Swedish service. But when the Swedes stormed Varberg in August of the same

year he was robbed of all his possessions and taken in chains to Upsala.

Only at the request of the Scottish officers he was finally set free. He

was raised to the Swedish nobility in 1579, after showing evidence of his

birth. From 1582 he held the estate of Hedenlunda, which remained the main

seat of the family for two hundred years. In 1585 he received letters from

James VI granting him the right to bear "the arms of his blue field." In

1604 he was Gentleman of the Bedchamber at the court of Charles IX, and

later Colonel of a regiment that he had enlisted in Scotland. In 1609 he

was Inspector-general of all foreign troops, and in 1611 he was sent as

Swedish envoy to Russia. He was married to Brita Soop. He died in 1618 and

his wife in 1622. The two lie buried under a lovely stone in Vadsbro

Church. He had a brother, Anders Stuart, who was an officer. The family

still survives in Sweden.

Hans Stuart’s grandson,

Carl Magnus Stuart, was the country’s foremost fortifications officer at

the turn of the 17th-18th centuries, and was military tutor and

adviser to the young Charles XII.

The Colquhoun Family

The Scottish family of

Colquhoun have been in Sweden for 400 years. In the middle of the 1560’s

two brothers, William and Hugh Colquhoun, came to Sweden as officers with

a Scottish troop of horse that had been enlisted for the bloody war

between Sweden and Denmark, which then surged back and forth in south

Sweden. Their father was apparently Sir Alexander Colquhoun of Luss and

Colquhoun and the mother a Buchanan. From the time they arrived in Sweden

they were called Cahun.

Willem used a signet with

the same Cross of St. Andrew as the Scottish family bore in its arms. He

commanded a troop of Scottish horse at the battle of Axtorna in 1565.

We learn nothing of his fate after 1574. He possibly accompanied the

large Scottish force that was sent out to the fighting in Russia. The

archives provide more details on his brother Hugh, who was one of the

first foreign officers to defect from Eric XIV in 1567 and to join Eric’s

brother Duke John, later John III. When the Scottish infantry under

Archibald Ruthven arrived in Stockholm in 1574, he was accused of

slandering its officers and, on the demand of his countrymen, was

executed. John III made generous provision, however, for his family. The

present Swedish family of Gahn stems from his son Peter Cahun, who became

part-owner of the Falun copper mine.

One of his descendants was

raised to the nobility in 1689 under the name of Canonhielm. Later on,

General Pontus Gahn, when he became aware of his noble Scottish origin,

took the name of Gahn of Colquhoun when he was raised to the nobility in

1809.

A roll of men in Willem

Cahun’s troop is extant from 1569. It was 100 men strong, and the other

officers were Hugh Cahun, David Cor, Thomas Bachnari, Willem Moncrieff and

Robert Crichton. The other ranks include such names as Arbaterr, Campbell,

Douglas, Hamilton, Maxwell, Muir, Ogilvie, Ramsay, Ross and Stewardt.

Henrik Leyell and Willem Wallace were later to command their own troops.

Scottish Merchants

During the 16th century,

and later, the Swedish Crown opposed all commerce other than by the

burghers of the cities. In 1572 a general mandate was published from John

III’s chancellery concerning "foreign cavalrymen, Germans, Scots and

others", which had begun to travel around the country, selling

merchandise. They were now offered special benefits if they would settle

in the cities and become real burghers. The names of many of these

"country merchants" are Scottish, particularly in Smâland and

Vastergotland. Many of them concealed their identity under such names as

Jacob skotte (James the Scot), but others are easier to identify.

One Hans Moncur, for example had served in 1569 in Willem Cahun’s troop of

horse and appears in 1587 as a country merchant in Västmanland. Another

man, who paid tax 1587-90 as a country merchant in the parish of Luleâ, by

the nothern tip of the Baltic, may also have belonged to this troop. The

merchant we know most about is one Hans Waterstone. Waterstone was

prosecuted in Vadstena in 1579 for illegal commerce, and claimed on that

occasion to be a burgher of Linkoping. The following year saw him before a

court in Soderkoping. In 1582 he was a merchant (possibly also a burgher)

in Stockholm, and in 1587 he was charged once more with illegal commerce

in Vadstena, and he seems on this occasion to have been in partnership

with Hans Moncur. In the 1590’s he was an officer, serving in Livonia. In

1608 we hear of an estate forfeited by him in Vadstena.

It is also clear that many

of the Scots who had come to Sweden to serve with the cavalry later

settled down as burghers in the small towns. We meet, for example, such

names as Willem Hamilton (Karlstad 1598), Willem Munkrij or Magkryff (Marstrand

1588 and 1599) — probably the Captain of Horse at Wesenberg in 1573 who

was charged for going to the assistance of the Scottish foot soldiers —

and Thomas Ugleby Ogilvie — (Nykoping 1600). From the middle of the 16th

century merchants of Scottish origin also began to infiltrate the larger

cities, particularly Stockholm, Kalmar and Ny-Lodose (the predecessor of

Gothenburg). They came to begin with from Danzig and Elbing, the bases for

trade already established south of the Baltic, but later years saw also a

direct immigration from Scottish ports. These Scots were relatively few in

number, but through their resources of capital they played an important

role in the Swedish export and import trade towards the end of the

century. The burghers of Ny-Lodose included in the 1590’s such men as

magistrate Jacob Gatt, Jacob Leslie, Jacob Reidh and Petter Forbos. Living

in Stockholm in the 1580’s were merchants Anders Lamiton, Erland Mackner

and Lucas Lami, and craftsman Gilbert Silber. The most prominent Scot

living in the city at that time was Blasius Dundee.

Blasius Dundee

Blasius Dundee is the most

outstanding of the Scottish burghers in Stockholm. He was of bourgeois

origin, and was born before 1550.

The use of Swedish wooden mazers - "kasor",

"Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus"

by Olaus Magnus 1555.

We first learn of him in

Sweden in 1576. In the following year he delivered supplies and acted as a

banker for the campaigns of John III. He was paid in kind, with products

that he exported on his own ships. A burgher of Stockholm from 1583,

he was always one of those who paid the highest taxes. He owned

several houses in Stockholm. 1586-96 he was one of the City Elders.

In 1595 he extended large cash loans to the Swedish Crown, which were not

finally repaid until 1616. In 1594 he was one of the burghers who

represented the city at the burial of John III and the coronation of

Sigismund in Upsala. In 1599 he was accused of having conspired with

Sigismund, but refuted the charge.

Blasius Dundee was married

three times. His first wife was one Katarina Andersdotter. The fragment of

tombstone that is preserved with the date 1586 is considered to be hers.

His second wife, Malin

Willemsdotter, was probably of Scottish birth. In 1599 he accused her of

adultery with several men, including a Scottish clerk of Muster Roll named

Willem Brun. The trial, which ended in a settlement, gives us a glimpse of

the life of the Scots in Stockholm. We learn that Malin had embroidered a

handkerchief for a Polish officer, and that she had accepted his portrait.

Willem Brun and another Scot, Thomas Clement, had given Blasius a glass

window with their names on it. When Malin saw this, she removed the pane

with Thomas’ name and put in one with her own. Finally, we learn that in

her sewing basket there lay copies of a couple of ballades.

His third wife, Anne

Werner, bore him three children. When he died in 1621, he must have

attained a considerable age. |