|

During that period of the

monarchy which preceded the eleventh century the revenues of the State were

derived from the rents of demesne lands, export and import customs, fines,

and escheats. These revenues were collected on the unsupported authority of

the sovereign by officers whom he personally named. Up to the reign of

Malcolm Canmore there is no record of any national convention or other

legislative assembly. Subsequently legal procedure in Scotland began to

assume an English impress. Scottish sovereigns became familiar with Anglican

modes. Margaret, Queen of Malcolm Canmore, whose pious and useful life

closed in the Castle of Edinburgh on the 16th November 1093, was daughter of

Edward, last of the Anglo-Saxon kings. A connection with England was renewed

when in the year 1100 Maud, daughter of Malcolm and Margaret, espoused Henry

I., and so became the English queen. At the court of his sister Maud, David

I. mainly resided, till in 1124 he succeeded to the Scottish throne. A

national convention was held in the reign of his brother and predecessor

Alexander I., when in 1107 it was declared that Turgot was chosen bishop of

St Andrews "by the king, the clergy, and the people." William the Lion, who

commenced his reign in 1165, assembled several conventions, which transacted

business as representatives of the clergy, the barons, and probo homines.

These last were vassals of the crown, who, bound to render suit and service

at the king's court, were on this account included in legislative

announcements. Practically they took no part in public concerns, leaving

these to be conducted by the sovereign, the clergy, the officers of State,

and the great barons.

At a, National Council held in 1230 there were present one bishop, one

prior, two earls, one of these being one of the two Justiciars, the High

Steward, and one other baron. The Assembly of Nobles which on the 5th

February 1283 acknowledged the Maiden of Norway as heir to the throne,

consisted of thirteen earls and twenty-four great knights and barons. And

the Convention at Brigham of March 1280, relative to the proposed marriage

of the infant queen, included about fifty earls and barons and a like number

of ecclesiastics. The first Scottish Parliament met at Scone in 1292 on the

summons of the king, John Baliol.

Burghs were first recognized in connection with

national affairs, when on the 23rd February 1295 the seals of six burghs

were affixed with those of the nobility and barons to an instrument relative

to an alliance with France. In the Parliaments of Robert I. are named along

with the clergy and barons, "the chief persons of communities," till, at a

Parliament held at Cambuskenneth on the 13th July 1326, were voted to meet

war and other costs, "a tenth penny of all rents" by those described as

earls, barons, burgesses, and free tenants of the realm.

On the part of the lesser barons—the probi

hominies of the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth

centuries.—attendance at the king's court, and latterly in Parliament, was

felt as an intolerable burden. In order to their relief it was agreed in a

Parliament held by David II. at Scone in September 1367 that they might be

allowed to complete their harvests, by leaving public business to the care

of a Committee. Eighteen months later, when a Parliament assembled at Perth

in February 1369, business was delegated in like manner. Two Committees were

chosen, of which one was subsequently known as the Lords Auditors, the other

became prototype of two distinct bodies—afterwards to be prominently

associated with national affairs—time Privy Council and the Lords of the

Articles. Consisting of twenty-seven members, the Committee of the Articles

were nominated at an early stage of Parliamentary business, when the House

adjourned in order that they might prepare the bills. And when Parliament

reassembled, it was simply, without discussion, to grant confirmation. In

1535 the Lords of the Articles were authorized to make Acts with the whole

power of Parliament; they exercised this power by imposing a tax. Referring

to his absolute authority in Scottish Parliaments, James VI., in a speech

which lie delivered at Whitehall in 1607, spoke thus: "This I must say for

Scotland, and I may trewly vaunt it; here I sit and governe it with my pen.

I write and it is done, and by a clearke of the Councell I governe Scotland

now, which others could not do by the sword. For here must I note unto you

the difference of the two Parliaments in these two kingdomes. For there,

they must not speak without the Chancellor's leave; and if any man do

propound or utter any seditious or uncomely speeches, lie is straight

interrupted and silenced by the Chancellor's authoritie. . . If any man in

Parliament speake of any other matter than is . . . first allowed by mee,

the Chancellor tells him there is no such bill allowed by the king.. . . If

[in any law] there be anything that I dislike, they rase it out."

The Committee on the Articles underwent various

changes. Under Charles I. in 1633 it was ruled that the bishops make choice

of eight lay peers; and that the peers elect eight bishops, when the sixteen

so chosen should add to their number eight commissioners of shires, and

eight of burghs. Parliamentary attendance was reduced to two days, the first

for choosing the Lords of the Articles, and the second to sanction what

their lordships had devised.

At the commencement of the Civil War, the

Committee of the Articles was abolished. During his ascendancy, Cromwell,

who sought a common Parliamentary representation of the three nations,

appointed for Scotland thirty members, of whom twenty were to sit for

counties, and ten for burghs. But this node being generally obnoxious,

Scotland was during the Commonwealth represented in the single legislative

chamber by officials of the government, or by English officers. The former

Parliamentary system with the Committee on Articles was revived at the

Restoration. In 1690, when the Scottish Convention agreed to accept the

government of the Revolution, they stipulated that the Committee of Articles

should cease.

What had mainly tended to the ascendancy of the

court, by the ready acquiescence of the Estates in the delegation of their

authority, was the poverty of the lesser barons. While burgesses were

entitled to elect representatives, a corresponding privilege was denied to

landowners, who were constrained, under a penalty, to attend personally.

That attendance involved the heavy cost of taking part in a pageant which

accompanied each Parliament at its opening. This was called the Riding of

the Parliament. Members of the three Estates assembled at Holyrood Palace,

each attired according to his degree, and mounted on richly caparisoned

horses and preceded by trumpeters, rode to the place of meeting. In the

procession the commissioners of burghs and the lesser barons rode first,

next the great barons and the clergy. The great officers of State followed

up, preceded by the Lord Lyon, heralds, and pursuivants, bearing the

natioval insignia. Last rode the Sovereign, attended by his pages, and

followed by the royal guard. Entering the Parliamentary chamber, the members

were addressed in a discourse by the court preacher, and after some routine

business, were expected to return to Holyrood. To the lesser barons the

ceremony was a cause of embarrassment. Their personal and horse trappings

were understood, in most instances, to exhaust the revenues of a year. James

I. sought to relieve the rural landowners of Parliamentary attendance, by

allowing a representation, but his proposal was at the time not carried out

At length by a statute passed in 1567 the barons were allowed to send

commissioners from their several counties, but were also called upon to

defray the costs of the elected. The allowance as costs was in 1661 fixed at

£5 daily from the day of leaving home to that of return; but this sum was

greatly inadequate. Those entitled to vote at the election of commissioners

of shires were by statute in 1585 declared to be "such as have

forty-shilling land in free tenandry held of the king." This qualification

was undisturbed for two centuries and a half.

Prior to the reign of Robert II. (1371-1390) the

Acts of Parliament were composed in Latin, a language in which hitherto all

public business and private correspondence had been conducted. The earliest

existing MS. which presents any considerable body of the laws in the

vernacular is ascribed to the year 1455; it is preserved in the Advocates

Library.

From the earliest times the Scottish Parliament

met in one house, but the members were not allowed to occupy the same

footing, for the great barons and the clergy sat on benches, the officers of

state on the steps of the throne, and the commissioners of shires and burghs

upon "furmes" Parliaments assembled at Cambuskenneth, Scone, Perth, and

Aberdeen, commonly at Edinburgh, where the king chiefly resided. At

Edinburgh the Estates convened so early as the reign of King Robert the

Bruce. The Parliament Hall of Edinburgh Castle (now the garrison hospital)

was reared in 1434. A. spacious chamber, 80 feet in length and 30 in

breadth, with an open chestnut roof, richly decorated, it was appropriated

to other uses prior to the 3d of February 1489-90, when we find that the

Estates assembled in the Tolbooth. The Parliament House of Stirling Castle,

a Norman structure, with a hall 120 feet long, was used up to 1571, when in

September of that year a Parliament was there held in presence of the infant

James VI. The structure was then in considerable disrepair, and when the New

ToIbooth at Edinburgh was reared in 1561, it was opened as the Parliament

House. Within the New Tolbooth Charles I. held a Parliament in July 1633,

subsequent to his coronation. In the same vicinity, adjoining St Giles'

Church, a building was in 1640 reared for the accommodation of the Estates.

Of this fabric the great chamber, still known as the Parliament House, forms

the hall of the College of Justice. Measuring 122 feet in length by 40 in

breadth, with an open oak roof, springing from corbels of various designs,

it forms an apartment admirably adapted to its present purpose. In the

Laigh Parliament House were for a time accommodated the records of the

kingdom.

Besides enacting laws, the Scottish Parliament

imposed taxes for ordinary and extraordinary purposes, the latter including

the coronation and baptismal ceremonies, the destruction of freebooters, and

the suppression of insurrections. Taxes were ordinarily imposed upon the

land, but in 1692 Parliament levied a poll-tax with a view to meeting the

arrears which had occurred in the remuneration of public officers and of the

army during the four years which had elapsed since the Revolution. By the

poll-tax statute, every person of both sexes, whether householders or

lodgers, were required to pay into the Exchequer 6s. yearly. A cottar who

followed a trade was also required to male a payment of 6s. From servants

who received more than £6 of wages were levied one-twentieth part, and from

tenants one merk per hundred of the landlord's valued rent. Burgesses of

royal burgles were assessed according to means and substance. From persons

who held rank as gentlemen were exacted £3, and from landowners with £50 and

under £200 of valued rent, £4; with £200 and under £500, £9; and with £500

and under £1000, £12. Those whose valued rents exceeded £1000, and all

knights and baronets, were required to contribute £24, while barons were

expected to pay £40, viscounts £50, earls £60, marquises £80, and dukes

£100. The poll-tax proved unpopular, and was discontinued.

The Scottish Parliament ceased when, on the 1st

May 1707, the political Union with England was fully consummated. In the

Treaty it was provided that Scotland should in the Parliament of the United

Kingdom be represented by sixteen Peers in the House of Lords, and in the

House of Commons by forty-five members. By the Reform Act of 1868 the

representation in the Lower House was increased to sixty.

With the event of the political Union it was

hoped by English statesmen that the Scottish national insignia, consisting

of the crown, sceptre, and sword, would be borne to the Tower of London, but

the removal of the symbols was disallowed. In a large wooden chest they were

deposited in the Crown Room of Edinburgh Castle, of which the door was made

fast.

The original insignia of the Scottish monarchy,

including the crown royal and the coronation stone, were by Edward I.

removed to London in 1236, when John Baliol was deprived of his sovereignty.

A coronet with which, in the absence of the ancient crown, Robert the Bruce

was crowned at Scone, was also snatched by English invaders. But a new crown

constructed for the coronation of David II. in 1329 continued to be used at

every coronation till 1650, when it was at Scone placed on the lead of

Charles II. Elegantly fashioned, and richly adorned with jewels, it was in

the reign of James V. surmounted with two concentric circles, displaying at

the point of intersection a mound of (old, enamelled, also a large cross

partee. The circumference of the crown is 27 inches. The sceptre was

constructed for James V. in 15:36 during his visit to France. To James IV.

the sword of state was in 1507 presented by Pope Julius II.; it is

accompanied by a sheath, which is adorned with filigree work, embracing

Papal emblems interwoven with acorns and oak leaves.

The regalia were not only used at coronations,

but at the opening of every Parliament were borne in procession, and in the

place of meeting deposited on a table in front of the throne. When the Lord

Chancellor presented a bill for royal sanction, the Sovereign or the King's

Commissioner touched it with the sceptre, an act which gave effect to it as

a legal statute.

After being used at the coronation of Charles

II. in 1650, the national symbols were removed for safety to the Earl

Marischal's castle of Dunuottar. The Earl being a prisoner in England, the

defence of the castle was entrusted to Captain George Ogilvie of Barras,

with a garrison of one hundred men. Faithful to his trust, Ogilvie nobly

held out, but as the army of the Commonwealth had triumphed everywhere,

permanent resistance was hopeless. What strength might not secure was

attained by stratagem. On the counsel of the Dowager Countess Marischal, Mrs

Grainger, wife of the minister of Kinneff; a parish in the vicinity, asked

permission of the English commander to visit in the castle the Governor's

wife, her friend Mrs Ogilvie. The commander having acceded to her request,

Mrs Grainger and her waiting-maid entered the stronghold. After a brief

interval they returned, each bearing a supposed gift from the governor's

wife. For Mrs Grainger held in her lap what passed as a bundle of lint,

while her attendant carried what was described as the hards of flax. To

those possessing the deeper penetration of the north it would have appeared

obvious that a beleaguered garrison would not readily surrender any portion

of clothing or the material for producing it; but Cromwell's commander and

his staff happily were unsuspecting. The commander, it is alleged, helped

Mrs Grainger to her horse, and if this tradition is correct, he had some

opportunity of remarking the weight and form of her burden. By the

handmaiden were borne the sceptre and sword of state. Never before had

Scottish females entered on so daring an enterprise.

The -women quitted slowly the precincts of

Dunnottar Castle, but hastily traversed the remainder of their journey to

Kinneff Manse, about five miles distant. There did the venerable Countess

Marischal hail the success of a stratagem which concerned the honour of the

kingdom and the credit of her house. The minister of the parish hastened to

complete what his wife had begun so skilfully. The sequel is depicted in a

narrative which Mr Grainger supplied to the Dowager Countess: "The 31st

March 1652. I, Mr James Grainger, minister at Kinneff, grant me to have in

my custody the honours of the kingdom, viz., the crown, sceptre, and sword.

For the crown and sceptre I raised ane pavement stone just before the pulpit

in the night tyme, and digbed under it ane hole, and putt them in there and

filled up the hole, and Iayed down the stare, just as it was before, and

removed the mould that remained that none would have discovered the stone to

have been raised at all. The sword again at the west end of the church

amongst some common seatts that stand there, I digaed doun in the ground

betwixt the two foremost of these seatts, and laid it doun, within the caice

of it, and covered it up, so that removing the superfluous mould, it could

not be discovered by anybody. And if it shall please God to call me by death

before they be called for, your Ladyship will find them in that place.—JAMES

GRAINGER."

Mr Grainger survived the Restoration, and was

privileged to see "the honours" transferred from the earthen floor of his

parish church to their former place of keeping—the Crown Room of Edinburgh

Castle. There were the regalia, on 26th March 1707, locked up and secured.

So long as the regalia rested in the Union

strong box, Scottish nationality was asleep. Scotland at the Union had two

Secretaries, the number in 1714 was reduced to one, and when the Marquis of

Tweeddale retired from the office in 1746, it was not filled up. What

Scottish business fell to be transacted was nominally entrusted to the Lord

Advocate, but the bulk of government patronage was really in the hands of

one or two powerful families, who therewith aggrandized their friends and

rewarded their adherents. Professedly on account of the two Jacobite

insurrections Scotland was denied the privilege of embodying a militia. The

royal palaces were, without repair, allowed to crumble into ruins. To a

grazier were leased the royal gardens at Stirling, while the other precincts

of the palace were appropriated to hog-feeding, or allowed to become the

resort of gamblers and tinkers, and a haunt of the profane. Such indeed was

the condition of the precincts of Stirling Castle so lately as 1855, when it

was the privilege of the present writer to induce the authorities to promote

a salutary change. Till about thirty years ago, Stirling Castle was in its

various structures exposed to those modernizing changes which have deprived

it of its ornaments. The older palace was early wrecked, and in 1777 the

highly ornate palace of James V. was dismantled of its fittings, including

its superb oak carvings, and ruthlessly converted into a barrack. In like

manner were broken up the Parliament House and the Chapel Loyal, the former

being converted into a barrack, the latter into a store of arms.

At Edinburgh was experienced as keenly as in the

provinces the bitterness of alien rule. Within the Castle, the historically

precious chapel of Queen Margaret was unroofed, and allowed to fall into

decay. An hospital was formed of the ancient Parliament House. The royal

apartments, in one of which James VI. was born, were converted into a

canteen, or rooms in which soldiers were indulged with liquor. Amidst the

remonstrances of the citizens and the protests of the Corporation, a block

of barrack rooms was reared in the Castle, which, sufficiently adapted for a

rural mill-work, was calculated to deface a city otherwise remarkable for

architectural beauty. The palace of Holyrood was allowed to crumble, and its

Abbey Church so to suffer from neglect that its roof, in December 1768, fell

into the interior, crushing in its fall the gracefully sculptured columns,

and wrecking the royal tombs. Then children began to use in their diversions

the skulls and other bones of Scottish princes. The skulls of Lord Darnley

and Queen Magdalene Were exposed and borne off. Less than a century ago, the

Lord high Commissioner to the Church of Scotland was compelled, in lack of

accommodation elsewhere, to hold his levees in a tavern; and so lately as

1844 did the General Assembly meet for the first time in an appropriate hall

provided by the State. Within the last forty years the Lords Ordinary of the

Court of Session listened to pleadings and gave judgment amidst the stir and

bustle of the Parliament House.

Nor were the national registers better cared for

than the public buildings. The paramount duty of preserving the records, not

only for legal and constitutional purposes, but as monuments of history, was

suggested by the Lord President Forbes, and about eighteen years subsequent

to his decease, the sum of £12,000 for the erection of a Register House was

granted by the king from the fund of the Forfeited Estates. But this grant

was for nine years resolutely withheld. At length on the 27th June 1774 the

Register House was founded, but funds for the completion might not be had

till half a century later.

Prior to the depositure of the national records

in the Register House, they were kept in hogsheads in the Laigh Parliament

House, of which the northern wall was bordered by the damp earth of St

Giles' churchyard. The custodiership being loosely discharged, volumes were

borrowed and lost. A portion of the Records of the Privy Council were bought

as waste paper, and in 1794 eight volumes of the Register of Sasines were at

a public sale, purchased by a bookseller, who honourably restored them. The

latter incident led to a movement, which, iii the first instance fruitless,

aroused a spirit of inquiry. Some influential person, seeking to confirm his

title to certain lands, hoped to procure evidence from records not contained

in the hogsheads. And a notion possessed him that what was lacking might be

found in the Crown Room. Interesting the Barons of Exchequer, they procured

a royal warrant authorizing an examination. The instrument being directed to

the Great Officers of State, these, on the 22d December 1794, assembled in

the Castle. Under the guidance of the Governor, they proceeded to the Crown

Room. In the words of their report, it was "secured by a strong outer door

of oak wood and two strong locks, the keys of which were not to be found,

and the only window barricadoed on the outside by cross-bars of iron, and a

wooden frame within." The report continues, "when one set of doors was

forcibly entered, another set, consisting of strong iron bars, had to be

wrenched open." When at length the interior was reached, there was found in

an arched chamber, and resting under six inches of dust, a large oaken

chest. Though this was large enough to contain many registers, the

Commissioners on examining their warrant concluded that lawfully they might

not proceed further. So the search was abandoned, the strong barricades

which secured the apartment being stoutly replaced.

The uncertainty which attended the existence of

the national insignia was a source of deep concern to Sir Walter Scott, who

waited a suitable opportunity for instituting an inquiry. His personal

intimacy with the Prince Regent at length enabled him to effectuate his

purpose. By a. warrant from the Regent, dated the 28th October 1817, the

Great Officers of State, including Sir Walter as a Principal Clerk of

Session, were appointed Commissioners to enter the Crown Room, and therein

make due search for the regalia. On the 4th February 1818 they executed

their mission. As the key of the great chest could not be found, the lock

was forced. On the lid being raised were found, under several inches of

dust, the long-hid treasures. These were the crown, the sceptre, and the

sword of state; also a gold-topped silver rod, which was the Chancellor's

mace. With the exception of the sceptre, which was slightly bent, the

insignia were in excellent preservation. They are now exhibited in the Crown

Room.

Of the ancient Officers of State the highest in

rank was the Chancellor. Constituted by Alexander I., he in the reign of

Alexander III. received a salary of £100. The royal fiefs were administered

under his authority, and lie could grant or recall royal charters. Keeper of

the Great Seal, lie by its use rendered valid the regal writs. As President

of Parliament, he was conversant both with the civil and the canon law; and

usually chosen from among the clergy, he brought to that order much of the

influence which it possessed prior to the Reformation.

When Walter, son of Alan of Oswestry, was by

David I. appointed civil administrator of his household, lie was styled

senescale, that is, senior servant, the seniority implying dignity and rank.

The office so created became that of High Steward, which in the person of

Walter's representative, Robert II., was merged in the monarchy. As a

substitutional officer James I. appointed a Master of the Household, who

furnished and arranged the castles and palaces, and was chief of the royal

henchmen, pages, and yeomen. A Constable was first appointed in the reign of

Alexander I.; he kept the king's sword, led the royal army, and was chief of

the barons. From the reign of David I. the office was hereditary in the

family of De Morevile, and when that family ceased it was combined with the

office of March-scale, or Marischal. The Marischal was keeper of the

stable and master of the horse; he enjoyed high rank and exercised a

powerful authority. The Marischal's office became hereditary in the family

of Keith.

The Chamberlain had (as the name of his office

implies) charge of the camera or treasure-chamber. He presided in the

exchequer court, which derived its name from the chequered cloth which

covered the table at which lie sat. Under his presidentship assembled the

Court of Four Burgles, by which the laws of trade and commerce were framed

and administered. To the Chamberlain those who considered themselves

aggrieved by the decisions of inferior courts prosecuted an appeal; and the

penalties imposed by his decisions became a portion of his revenue. These

must latterly have been very considerable, for while in the reign of

Alexander III. the Chamberlain's salary was £200, his receipts for feudal

casualties, escheats, and other perquisites, amounted in a single year to

£5313. To lessen the power of the Chamberlain, which had become formidable,

James I. established the office of Treasurer. To the Treasurer the sheriffs

and other collectors of the national revenue presented their accounts at

intervals. Subsequently a portion of the Treasurer's duties were discharged

by the Comptroller, who superintended the royal manors. This officer also

exercised those functions which at a modern period were discharged by the

Barons of Exchequer. In 1596 James VI. appointed as Great Chamberlain the

Duke of Lennox, the office, which had become honorary, being made hereditary

in his house.

James I. appointed a Lord Privy Seal. By

impressing a small seal or signet, this great officer rendered valid writs

and gifts less important than those reserved for the great seal in the

keeping of the Chancellor. The Secretary was an officer who constantly with

the king, received memorials and complaints, and was by the sovereign

instructed how to deal with or dispose of them. By his signature royal

decrees were made valid. The Lord Clerk Register was keeper of the public

archives and Clerk of Parliaments; he also kept the minutes of the Privy

Council and of the higher judicatories. The King's Advocate was the

sovereign's legal adviser, and by royal authority prosecuted defaulters in

the public courts.

These, high officers, deriving their honours

from the sovereign, were official members of the Privy Council. They also

had seats in Parliament, but when the number of State offices had

indefinitely increased, it was in the year 1617 found essential to restrict

to eight those permanently invested with legislative authority.

During the reign of David II. a Secret Council

was nominated. The king was without issue, and as the succession to the

throne was attended with difficulty, it became essential that the question

should be considered by the officers of State in secret, also by other

councillors of position and experience. The difficulties to be surmounted

were these. On the one hand it was known that the king had indicated a

willingness to transfer the sovereign authority to the English monarch,

while on the other hand Robert the Steward, next in the order of succession,

was twice married, and his first wife, Elizabeth Mure, was within the

degrees forbidden by the canon law, while his marriage had lacked the Papal

sanction. By those who joined in the secret deliberations, it was resolved

that the independence of the kingdom be openly maintained, also that the

crown be settled upon the Steward and his eldest son by Elizabeth Mure. When

that son, who afterwards reigned as Robert III., was from sickness unable to

conduct the Government, his elder son, the Duke of Rothesay, was appointed

to administer in national concerns along with a council of eighteen persons.

Councils for advising the sovereign were thereafter appointed as necessity

arose, till 1489, when a Privy Council for aiding the royal authority was

constituted permanently. Of this body, the records since the year 1545 have

been preserved, and under careful editorship, are now being issued in

printed volumes by the Lords of the 'Treasury.

The Privy Council usually consisted of fifty

members, those additional to the officers of State being specially chosen by

the sovereign. As the executive of the State, the Privy Council. enforced

police regulations, and determined important questions relating to civil and

criminal affairs. In judicial concerns it was indirectly associated with

another court—the Lords Auditors of Parliament—which, like the Privy

Council, was entitled to review the judgments and decrees of inferior

judges. Changeable with each Parliament, the Lords Auditors consisted of six

churchmen, six great barons, and five commissioners of burgles, of whorl

several were ecclesiastics. For judicial duties, neither the members of the

Privy Council nor the Lords Auditors were specially qualified; and to remedy

the defect, James V. in 1532 established, under Papal sanction, a new

tribunal intended to combine the functions of the Lords Auditors and of the

Privy Council. Of this tribunal, the judges were styled Lords of Council and

Session, and there were, along with a president, seven lay and seven

clerical members. By the Pope it was understood that a churchman would

uniformly be Chosen o preside, and by churchmen was the presidential office

held till the Reformation. In 1579 the power of choosing a president was

granted to the court itself, but after some changes the right of nomination

was reserved for the Crown.

The ordinary lords were at first chosen by the

King and Parliament, afterwards by the latter. In the course of testing his

prerogative, Charles I., in 1626, displaced the Lord President and six

ordinary lords, the remaining eight being allowed to continue on obtaining

new gifts of their offices, thereby acknowledging that their former

appointments had lapsed on the death of the late kind. In the further

exercise of arbitrary power, Charles addressed letters to the Lords of

Session, commanding them in certain instances to delay judgment or to hasten

it. In a letter addressed to the Court of Session on the 25th November 1626

he, in a matter concerning the Earl of Murray, charged the Court "not to

medle." The abuses which attended such unworthy interference became

unendurable, and the priest-ridden monarch, in 1641, was necessitated to

agree that Scottish judges should not be appointed without Parliamentary

sanction. This provision was rescinded at the Restoration.

In 1640 the spiritual side of the Court of

Session was abrogated by statute. But the privilege possessed by the

sovereign of nominating unsalaried judges, styled Extraordinary Lords,

continued a source of irritation till the reign of George I., when these

supernumeraries were abolished. At its institution, the Court was endowed

with "10,000 golden ducats of the chamber," derived from the bishoprics and

monasteries; but the amount was levied so unsatisfactorily that in 1549 the

salary of an ordinary lord did not exceed £40. The salaries, augmented from

time to time, were, at the Restoration, equal to £200 sterling. In Queen

Anne's reign, each lord had a salary of £500. The present salary of a Lord

Ordinary is £3000, that of the Lord President £4800, and of the Lord Justice

Clerk £4500.

By Act I I George IV., the Lords of Council and

Session were reduced to thirteen. Formerly the fifteen judges sat together

in one court; but, according to modern arrangements, five judges styled

Lords Ordinary decide on all causes in the first instance, the remaining

eight judges being arranged in two distinct Courts, called the First and

Second Divisions, four sitting in each Court. In the First Division the Lord

President presides; the Lord Justice Clerk in the Second. To the First or

Second Division causes are brought for review from the Lords Ordinary, or,

in legal phrase, from the Outer Mouse. In the Court of Session legal

business long proceeded tardily, with the result that while law agents

became rich those involved in litigation were by slow stages severed from

their estates and homes. When in 1727 the celebrated Duncan Forbes of

Culloden became Lord President lie devised an Act of Sederunt, which

provided that no cause might be protracted in Court beyond the period of

four years. Prior to this provision many causes had been continued twenty

years, involving members of successive generations in legal uncertainty and

lamentable discomfort.

Collaterally with the Court of Session exists

the College of Justice, of which the judges are described as senators, and

which in its membership includes the whole legal faculty,—advocates,

writers, extractors, and clerks.

Prior to the Reformation a Consistorial Court in

every diocese was conducted by a judge named the Official, who was appointed

by the archdeacon. To the Official's adjudication were reserved matters

relating to legitimacy and divorce; also to movable succession, the

fulfilment of covenants, and cases of slander. By the Officials were

certified the Public Notaries, whose fitness and personal qualities largely

availed in tunes when four-fifths of the nation were unable to write. Ere

the Court of Session was established the chief legal business of the kingdom

was conducted in the Consistorial Courts of Edinburgh, Glasgow, and St

Andrews. Before the Reformation appeals from the Consistorial Courts might

only be determined at Rome. These appeals were prohibited in 1560, while on

the 8th February 1563 Consistory Courts were superseded by a principal

Commissary Court established at Edinburgh. Time Commissary Court, which

consisted of four commissioners or lay judges, was gradually merged in the

Court of Session. In 1836 it was abolished as a separate jurisdiction. By

the statute 4 George IV. c. 97 each county is formed into a separate

commissariot, the sheriff being commissary.

To the Lyon Court are referred all questions

relating to armorial bearings. The sole judge in this court is the Lyon

King, whose authority in Scotland is similar to that exercised in England by

Garter King of Arms. Lyon derives his title from his bearing a lion rampant

in the emblazonry of his official robe. One of his earlier duties was to

convey messages from the sovereign to foreign courts. He now appoints

messengers-at-arms and superintends them. On appointment Lyon formerly

underwent the ceremony of a coronation. Sir Alexander Erskine, Bart. of

Cambo, was on the 27th July 1681 crowned Lyon King at Holyrood Palace by the

Duke of York; he was the last who was so distinguished.

The Druids exercised the earlier jurisdiction;

they framed laws and executed them. Their courts and legislative assemblies

were held on natural or artificial eminences fenced by a ditch and rampart,

and which were styled mood-dun—that is, enclosed mounds. When the Saxon

superseded the Celtic tongue the name mod-dun was vulgarized into

maiden; hence the maiden castle of Edinburgh, the maiden craig of

Dumfriesshire, the maiden rocks of Carrick and Fife, and the maiden stones

of Ayton, Garrioch, Tullibody, and Clackmannan—all the localities so named

being associated with ancient courts.

But the scenes of early jurisdiction have in not

a few instances been distinguished as note-hills, mod being converted

into the Anglo-Saxon mote, and dun represented by its English

equivalent. There are mote-hills in the counties of Roxburgh, Dumfries,

Wigton, Lanark, Ayr, Stirling, Perth, and Aberdeen.

In memorial of the ancient ditch and rampart,

courts of law are still fenced by the macer in a form of words. The

mote-hill was latterly a place of execution. Thus on the mote-hill of

Stirling in May 1424, Murdoch, Duke of Albany, and several members of his

family, were publicly beheaded under the charge of treason.

Coeval with the Druidic age, and prior to the

Roman invasion, a species of legal government was conducted through the

instrumentality of a Toshach and a Maormar. The Toshach was an officer

racking with the Thane of the Saxons. Elected to his office by the chiefs of

a province, these submitted to his arbitration, and in the field accepted

his leadership. Galgacus was chosen Toshach by the Caledonians in their

early struggle with the Romans. The descendant of a Toshach whose power had

been prolonged was regarded as a prince, and latterly was crowned. The

Scottish King was a Toshach at the first. A '1'oshach founded clan

Mackintosh ; the name is in English the son of the Thane.

Exercising a separate and independent

jurisdiction, the Maorivar ruled over his clan, and became their supreme

lawgiver and judge; the subordinates of the Maormar were iifuovs, or lesser

judges. By Malcolm Canmore Maormars were designated earls, while Maors

latterly ranked as barons of baillieries, or inferior officers by whom the

mandates of provincial judges were put into execution.

Retributive justice, dispensed harshly to the

poor, was tardy among the opulent. At the dawn of history we find trial by

ordeal in full operation. A murderer taken red-hand was convicted summarily.

But when the criminal, whether charged with murder or theft, pleaded not

guilty, and could not be directly convicted, lie was allowed to clear

himself by corn-purgation. This was accomplished when a number of leal men

swore that they believed him guiltless. The compurgators varied from one to

thirty, but usually twelve persons were impanelled. If corn-purgation

failed, the accused person appealed to the Divine judgment by challenging

his accuser. Judicial combats were witnessed by churchmen in the belief that

the innocent would triumph. Knights were allowed to do combat by proxy.

Accused persons might elect to be tried by ordeal. The administration of the

ordeal was a monastic privilege. There was trial by fire, also by water.

Trial by fire was successful when the accused passed over a red-hot iron

unscathed, and by water when, if thrust into a lake, he swain safely to

shore. In the year 1180 it was ruled by statute, that "na baron have leyff

to bald court of lyf and lym, as of jugement of bataile or of watir, or of

het yrn, bot gif the scheriff or his serjand be thereat, to see gif justice

be truly kepit thar as it ow to be." [Innes's "Scotland in the Middle Ages,"

Faro., 1869, 8vo, pp. 183-7.]

Trial by the right of wager in battle existed in

the reign of David I., the accused being allowed to elect this mode of

proving his innocence in preference to "the purgation of twelve lead men."

In 1230, during the reign of Alexander II., it was provided by statute that

any one acquitted by an assize should not for the same offence be required

to submit to an ordeal.

With compurgation and ordeal subsisted a system

of compensation, whereby those guilty of public or private offences made

recompense both to the persons injured, and also to the State. In the

earlier portion of our written law rates of compensation are enumerated. The

king is valued at a thousand cows, the king's son and an earl at one hundred

and fifty cows, and a villein or ceorle at sixteen cows. A married woman is

estimated one-third under the value of her husband. For the wounding of an

earl the compensation was nine cows, of a thane three, and of a serf or

ceorle one. Next to the revenues derived from the Crown lands and customs,

the escheats levied from delinquents proved from the thirteenth century to

the sixteenth a chief national resource.

For the more efficient administration of

justice, David I. appointed a supreme magistrate, or chief justice, styled

the Justiciar. He sat in curia regis, and from time to time held circuit

courts or justiceayres.

By William the Lion a second Justiciar was

appointed, with his jurisdiction in the Lothians. In the reign of Alexander

III. the chief of the Corny ns was appointed Justiciar of Galloway. On his

temporary conquest, Edward I. divided the kingdom into four judicial

provinces, two justices, an Englishman and a Scotsman, being appointed to

each province. On the restoration of the national independence, King Robert

the Bruce divided the country into two judicial districts, one to the north,

and the other to the south of the Forth. At the chief burgle of each shire

the Justiciar held a court three times a year, not only for administering

justice, but also in applying it. The fines imposed by the Justiciar were

paid into the exchequer, with the exception of a tenth reserved for the use

of the Church.

Though occupying the royal judgment seat, the

Justiciar was not by any of the kings invested with the entire judicial

authority. From the Parliament of 1488, James II. received the following

counsel:--"It is avisit and concluded, anent the furthe putting of justice

throw all the realnle, that our souerane lord sail ride in proper persoune

about to all his Aieris ; and that his Justice [the Justiciar] sall pas with

his hienes, to minister justice, as leis thoclit expedient to him and his

Counsale for the tyinle."

During a judicial circuit in southern counties

made in the same year James occupied two months; he was accompanied by the

Chancellor, the Justiciar, the Treasurer, the Clerk Register, and the

Justice Clerk. To the last named officer pertained the duty of making from

the records extracts of fines. These he placed in the hands of sheriffs,

stewards, and Dailies for recovery.

In 1491 Parliament ordered that justice-ayres

"be held, set and balden twis in the yere, that is to say, anys on the griss

[grass], and anys on the corne.

The proceedings of the justice-gyres from

November 1493, and ending July 1513, have been preserved. They are contained

in two MS. volumes which, on the 5th March 1880, were deposited with the

Clerk of Justiciary, after being for 150 years in the custody of the Faculty

of Advocates.

In 1526 Parliament enacted that "our Sovrane

Lord be personalie present at the halding of Justice Aires, geif it pleses

his Grace;" also "that na Justice Aires be haldin na part, without our

Sovrane Lord and his Justice be present." From ordinary justice-ayres,

appeals might be prosecuted to the King's Council, or to the Judicial

Committee of Parliament, or to Parliament itself. An appeal bore the strange

title of "ane falsing of dome."

The office of Justiciar shared the fate of other

great appointments of State by passing into a personal office. Early in the

sixteenth century it was conferred on the Earl of Argyle. The Earl is named

as Justice General in a court which, on the 25th August 152G, was held by

his deputy. In the reign of Charles I., Lord Argyle resigned the

appointment, but continued to act as Justice General for the sheriffdom of

Argyle and Tarbert, and of the Western Isles. After other changes, the

sinecure office of Justice General was in 1793 conferred on James, third

Dube of Montrose. By a legislative act passed 23d July 1830, the office was,

on the ceding of the existing interest, declared to be merged iii the Lord

Presidentship of the Court of Session.

Early in the twelfth century Scotland was

divided into sheriffdoms, which again were subdivided into wards or

bailiaries, or constabularies. The sheriff was king's lieutenant within his

particular district. The decrees of the courts of regality and barony were

executed under his authority, while from district collectors he obtained

their drawings of the public cess, and made account of them to the

exchequer. The office of sheriff became hereditary, the duties being

delegated to some one in the neighbourhood acquainted with legal affairs.

The chief landowner of a bailiary was, as a territorial magnate, constituted

the hereditary bailie. Each royal castle was governed by a constable, the

field of his jurisdiction, styled the constabulary, extending only to the

castle and its precincts. The constable of Roxburgh Castle was also sheriff

of the county. When a royal castle, as at Dundee, was associated with a

burgh, disputes as to jurisdiction between the constable and the magistrates

were not infrequent.

The coroner or crowner was constituted by Edward

I. It was his office to compel attendance at the law courts of those charged

with crime by seizing their cattle and corn, or securing them personally in

ward. An office so liable to abuse was early superseded; it only remains as

one of the civic titles enjoyed by the Lord Provost of Perth.

By the magistrates of burghs, especially those

of Stirling, Perth and Edinburgh, was possessed a jurisdiction in blood

wits, that is the right of trying and pronouncing judgment on persons

charged with murder. Thus John Cheislie of Dairy, the assassin of the Lord

President Lockhart, was, in 1689, summarily tried and condemned by the

magistrates of Edinburgh.

The Justice of Peace Court, instituted in 1609,

was empowered to check civil broils and punish those who were disorderly. In

1617 two Justices were appointed for every parish. Agrarian controversies,

or those relating to matters of husbandry, were settled in courts of birlaw.

Of these courts the judges were selected by husbandmen and approved by

sheriffs or other local magistrates. Birley-7nen attended to the rights of

outgoing and incoming tenants.

In 1672 was established the High Court of

Justiciary, which included five Lords of Session as commissioners or judges,

under the presidentship of the Lord Justice Clerk. With headquarters in

Edinburgh, the commissioners were authorized to hold circuit courts at

Dumfries and Jedburgli, Stirling, Glasgow and Ayr, also at Perth, Aberdeen,

and Inverness. From 1708 circuit courts began to be held at the places named

twice a year. While in inflicting punishment English judges are ruled only

by statute, those presiding in the, criminal courts of Scotland are

regulated by common law, that is, the practice of their own courts. That

practice has widely varied. The early punishments were singularly harsh. For

libelling the Lord Justice General, Dowall Campbell was, on the 24th

February 1673, sentenced to have his tongue bored, and to stand two hours in

the cuck-stool or pillory. For committing an assault, Andrew Drummond was,

on the 29th November 1703, sentenced to be set on the cuck-stool, and "there

to have his neck and hands put in the same, and his lug nailed thereto the

space of an hour." In a circuit court held at Stirling on the 20th May 1709,

the Lords of Justiciary sentenced Thomas Smyth and Janet Walker, for the

offence of adultery, "to be taken to the mercat cross of Falkirk, and there

to stand with a paper on their breasts bearing these words in great lettres,

`Thir are adulterers;'" also to he taken to the parish church of

Muiravonside on Sunday, the 29th inst., and to be placed at the church door

with the same placard pinned to their breasts. On the 21st November 1726,

Isobel Lindsay, whose illegitimate child had died soon after birth under

circumstances of suspicion, was by the High Court sentenced to be "by the

hands of the common hangman, scourged through the streets of Edinburgh at

the five usual places thereof, receiving at each place five stripes upon her

naked back, and thereafter to be carried to the Correction-house, there to

remain five months." On the 28th December 1726, George Melvil "a notour

thief," was "set on the trone, and had his nose pinched." For theft, David

Alison was, in October 1727, "pillored," "pinched in the nose," and "sent to

the Correction-house." In March 1728, Jean Spence, "a notour thief," was "pillored,"

"hir lug nailed," and "hir nose pinched."

There being no county or district prisons other

than the cells of the tolbooth, criminals were seldom sentenced to

imprisonment, and then only for periods rarely exceeding six months. Other

punishments were cruel, but imprisonment was farcical. Prisoners in the

tolbooths of Edinburgh, Stirling and Perth were till within the last sixty

or seventy years allowed to indulge a species of diurnal revelry. The means

of conducting their jollities were procured from the good-natured public, to

whom the prisoners lowered from a cell-window a small box, with the words

inscribed upon it, "Pity the poor prisoners." The box received contributions

of tobacco, liquor, and fruit. Banishment from the sovereign's "hail

dominions, furth of Scotland," or from one district of Scotland to another

was a common sentence. On the 3d July 1711, the Lords of Justiciary banished

Euphan Clark from the shires of Forfar and Perth, for ten years. And on the

16th March 1726, Thomas Pyne was banished from the country north of the Tay.

The ordinary place, of exile during the eighteenth century was "his

majesty's plantations in America."

In 1742, several persons who had violated the

sepulchres of the dead, Were sentenced to "scourging and banishment;" in

1823, an offence of the same character was visited with seven years'

transportation. So long as the publication of Popish doctrines was held to

be penal, those who exercised the rites of the Romish faith were subjected

to trial and punishment. At the Aberdeen circuit court, held on the 3d May

1751, Mr Patrick Gordon, residing in the castle of Braemar, was, on the

charge of being "Habit and repute a priest, jesuit, or trafficking Papist,"

found guilty on confession, and was sentenced "to be banished furth of

Scotland," "with certification that if ever he return, he, being still a

Papist, shall suffer the pain of death."

Ordinary sentences of banishment were

accompanied by the provision that the convicts would be publicly whipped in

the event of their covertly returning. Thus on the 6th October 1749, the

judges of the Inverness Circuit sentenced Christian Ironside to perpetual

banishment from Scotland, declaring that "if ever she shall return, she

should be taken to the head burgh of the shire in which she is apprehended,

and thereafter, upon the first market-day, whipped through the town by the

hands of the common hangman, receiving the usual number of stripes upon her

naked back." In November 1790, the magistrates of Stirling applied to the

Commissioners of Justiciary for counsel as to whether they would subject to

a public whipping, a woman who had returned from banishment, and was in a

state of pregnancy. Scourging through the market town was a common sentence.

So recently as the early part of the present century, persons convicted of

perjury were by the Lords of Justiciary sentenced to be scourged.

A first act of theft was, irrespective of the

value of the articles stolen, visited with some leniency; but conviction as

"a notour," or habit and repute thief, was ordinarily punished by death.

From 1790 to 1830, were in the High Court sentenced to death as "notour

thieves," in 1790, William Gadesby; in 1791, John Paul and James Stewart; in

1797, John Young; in 1799, Andrew Holmes; in 1811, Adam Lyell; in 1815,

William Honyman and John Smith in 1816, John Black; in 1817, John Long and

Thomas Mitchell; in 1819, Burne Judd and Thomas Clapperton; and in 1829,

Jacob Laird. The majority of these offenders had robbed with violence.

The last criminal who, in Scotland, was hanged

for forgery, was Malcolm Gillespie, a native of Dunblane. As an officer of

Excise, he had distinguished himself ill the revenue service, and Raving

retired on a pension, settled at Skene, Aberdeenshire. But he indulged in

financial speculations, and so fell into the offence for which lie suffered.

On the 28th September 1827, convicted by a majority of the jury, lie was

executed at Aberdeen on the 16th November following. It may be remarked that

the judge who passed sentence upon Gillespie was reputed for his humanity,

and that the advocate-depute, who resisted commutation of the sentence, was

known to the writer as mild, gentle and beneficent. But the humanities in

relation to the administration of the criminal law were sixty years ago most

imperfectly understood.

Prior to undergoing the highest penalty of the

law, criminals guilty of heinous offences were subjected to torture. In

1689, Cheislie of Dalry, who in a state of lunacy assassinated the Lord

President Lockhart, was at his trial examined by torture, and being

sentenced to death, was drawn on a hurdle to the market-cross of Edinburgh,

where his right hand was struck off. Thereafter he was dragged to the gibbet

in the Grassmarket. His body was thereafter hung in chains at the spot now

covered by the suburban mansions of Drumsheugh.

Alexander M`Cowan, who at the circuit court held

at Perth in May 1750, was convicted of murder and robbery, was sentenced to

have his right Band struck off prior to execution. The last criminal hung in

chains in Scotland, was one Leal, a messenger in Elgin, who at the Inverness

Circuit in 1773, was found guilty of robbing the post, and sentenced to

death. According to the Inverness Register of Deaths his. body was "hung in

chains, at Janet Innes's cairn."

The Justiciary Court now sits each Monday during

session, and in spring and autumn proceeds on circuit. In determining

causes, the Court is assisted by a jury of fifteen persons, chosen by ballot

out of forty-five jurors summoned. The jury may decide by a majority and in

addition to the usual deliverances of guilty or not guilty, they are

privileged to adduce a verdict of not proven. Formerly when a panel was

found not guilty, lie was, in the Justiciary Record, described as "clenzit;"

and when guilty, as "fyllit;" if sentenced to death, the recorder set forth

that he was "justifiet." Scottish jurors anciently pledged themselves to

maintain honest judgment in these tingling rhymes:

"We shall leil suith say,

And na suith conceal, for na thing we may,

So far as we are charged upon this assize,

Be God himsel, and be our paint of Paradise

And as we will answer to God, upon

The dreadful day of Dome."

As public prosecutor, the Lord Advocate was

formerly privileged to insist on the conviction of every prisoner by

menacing the jurors with "assizes of wilful error," that is with personal

penalties. Among the articles of grievance represented in 1689, the

Advocate's power of menace against juries was in-eluded. The right of menace

was withdrawn. By an act passed on the 31st July 1868, the Lord Justice

General, the Lord Justice Clerk, or any single judge in the Court, was

authorized to preside alone at any criminal trial.

Apart from the legal tribunals directly

sanctioned by the Crown, and in which the judges were justiciars, and

sheriffs, and other magistrates, both of county and burgh, there existed

courts of regality and barony, in which justice was roughly and arbitrarily

dispensed. For a feudal baron was practically invested in the sovereignty of

the territory conveyed to him by his charter, and even when the soil was

alienated, he continued toe excise a jurisdiction over those who occupied

it. And he was bound by no form of process, or restrained by any law,

statutory or common.

By statute four crimes, murder, rape, robbery,

and fire-raising, were, as "pleas of the Crown," reserved to the

jurisdiction of the King's judges; nevertheless the, lord of regality

asserted the power of dealing with every description of felony within his

feudal domains. He owned the right fosses et fitrca—that is, of punishing by

pit and gallows. Under the right f urea the baron could suspend on a gibbet

any of his vassals. The punishment fosses was of a twofold kind, since the

baron could immure in a pit or dungeon, or sentence to death by drowning. In

earlier times the regality prison was a species of pit, partly or wholly

underground. In the episcopal castle of St Andrews, founded by Bishop Roger

in the year 1200, a circular pit was formed in the rock on which the

stronghold rests ; it is nearly thirty feet in depth, with a diameter at top

of seven feet, and at base of twenty-seven. Therein offenders against the

Church or State were to be immured, and within it in 1544, under the charge

of heresy, were confined Friar John Roger prior to his secret assassination,

and in 1546 the pious reformer, George Wishart, previous to his martyrdom.

Regality prisons were latterly constructed under the arches of the older

bridges; also within the damp vaults of unoccupied castles. Within lochs and

ponds and in ditches female convicts were soused or drowned. In the

baronial. court of Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonston, held. at Drainie on the

25th August 1679, Janet Grant was, on a charge of theft to which she pleaded

guilty, sentenced to be drowned next day in the Loch of Spynie. From the

practice of the regality courts in extinguishing by water the lives of

female offenders, the government of James VII. adopted this mode of

silencing those women who ventured to impugn the king's arbitrary rule.

Charged with denying that James was entitled to rule the Church according to

his pleasure, Margaret M`Lachlan, aged sixty-three, and Margaret Wilson, a

girl of eighteen, were on the 11th May 1685 made to perish in the waters of

Blednoch.

In the earlier times lords of regality could

seldom read or write; hence they appointed bailies to preside in their

feudal courts, and otherwise to act on their behalf. Latterly a bailie was

appointed to preside in every regality court. The abbot and monks of Cupar

had on their home estate a principal bailie and two deputies. At the

Regality Court of Dunfermline certain officers connected with the several

districts of the jurisdiction were statedly examined concerning "bludes"—that

is, as to blood-shedding, whether by slaughter or wounding. On the 6th

October 1631 Andrew Alexander "gave up ane blude committed between William

Craik and James Barclay." By the Regality Courts of the north was exercised

a rigorous authority. Content in their records to enter the naives and

offences of accused persons, and the names of jurors, the result of a trial

was expressed by such words as "clenzit" or "convickt." To those in the

latter category are usually added the words "hangit" or "drounit." In the

Book of the Regality of Grant are presented sentences of unparalleled

severity. A lad, Donald Roy Fraser, charged with plundering "the socke of a

pleughe," was on the 14th June 1692 convicted on his own confession, when

the bailie of court, James Grant of Galloway, sentenced the prisoner "to be

nailit be the lug with ane Irene naile to ane poste, and to stand flier for

the spaice of ane hour without motione, and be allowed to break the griss

nailed without drawing of the nail." Having on the 22d May 1696 convicted

two ignorant persons, a father and daughter, of "stealing and resetting of

sclieip," the bailie of Grant ordered the delinquents to execution. But as

"supplication" was made for then by their neighbours, who besides offered to

become security for their future good behaviour, the bailie recalled the

death sentence, and substituted the following: "That Patrick Bayn be taken

immediately from court to the Ballow foot upon the moor of Ballintore, and

tyed thereto with hemp cords, and his body made naked from the belt upward,

and then to be scourged be the executioner with ane scourge by laying upon

his body twenty-four stripes to the effusion of his blood." The daughter was

sentenced to be "scourged with thirty stripes till her blood rin doun, and

thereafter to be banished from Strathspey." On the 2d September 1697

Ludovick Grant of that Ilk and his bailie, sitting on the bench together,

gave sentence that three persons guilty of horse-stealing should be carried

prisoners from the court to the pit of Castle Grant, there to remain till

Tuesday next, and under guard carried to the gallow-tree of Pallintore, and

to be all three hangit betwixt two and four in the afternoon till they be

dead." Another offender, Thomas Dow, was at the same time sentenced to be

bound to the gallows during the time of the execution, and thereafter to

have his left car cut off, and to be scourged and banished the country."

By regality courts were also determined civil

causes, and enacted binding regulations in regard to home products. Thus, on

the 29th January 1669, the judge of the regality court of Dunfermline

considering "the low pryces and waitts [weights] that is given for beer and

malt, ordained brewers and tipsters to retail and sell the same at sextein

pennies the pynt (instead of twenty) in the several parishes of the regality,

under the penalty of ten merkis scotts, toties guoties."

Through the claims asserted by the lords of

regality, criminals were not infrequently rescued, from the jurisdiction of

the ordinary courts. For a lord of regality could repledge a criminal in the

kings court by offering security that he would be tried in his own. Or he

might claim the right of sitting with the kin's judge, and thereby impede

the even course of ,justice.

Then the regality court, a less important feudal

jurisdiction was the court of barony. In the barony court a thief might be

punished by a capital sentence, if caught with the fang, "that is if

captured while bearing the article stolen." Yet sentence of death could he

pronounced only when the criminal was brought up within three suns after

committing his offence. Ordinarily the judge of the barony court was

expected to confine his administration to the enforcing of statutes for

preserving game, and protecting orchards and rabbit warrens. He might also

punish summarily those who wantonly destroyed certain saplings of the

forest. Hence the rhyme :—

Oak, ash, and elm tree,

The laird may hang for a' the three;

But for saugh and bitter weed

The laird may flyte, but mak naething be't."

Freeholders and landowners, disqualified from

holding regality or baronial courts, might act as soyters at a justice ayre.

Under authority of the ayre courts, soyters passed upon inquests, and

attended to the due execution of sentences. In south-eastern districts the

soyter exercised an authority similar to that of the provincial sheriff.

During the reign of William the Lion freeholders

were charged to attend the courts of justiciars and sheriff's. In 1449 the

command was renewed by statute, while in 1540 it was ordained that those

freeholders who owed suit and service in the regality and other courts were

to be fined for non-attendance. At "the head court of the bailyearie of

Cunningham held within the tolbooth of Irvine," on the 6th October 1674, the

depute "unlawed and amerciated ilk of the absentis in the soum of fyfteen

pund scotts money for their contumacie, couforme to the, act of Parliament."

And from "the Register of the Stewartry of Menteith" (1639-1733), we learn

that the heritors and freeholders were bound to be present at each of the

head courts held three times a year. On the names being called, those who

failed to answer were each amerced in a penalty of £50. In 1672 a statute

provided that all freeholders, magistrates, and dignified persons of the

shire should wait upon the Commissioners of Justiciary at their several

circuits. The rule being found burdensome, a new regulation was made on the

1st May 1760, whereby the attendance of noblemen, barons, and freeholders,

was dispensed with, the sheriff and his deputies excepted.

By public statute heritable jurisdictions,

realities, and constabularies, were, from the 25th arch 1748, abrogated and

dissolved, while a sum of £150,000 was granted from the exchequer as

compensation to the holders. To barons and their Dailies were reserved the

right of inflicting penalties against those convicted of assault, to the

extent of twenty shillings, or by "setting the delinquent in the stocks, for

any time not exceeding the space of one month." In civil causes

baron-bailies were allowed to decern for debts not exceeding forty

shillings, also for the recovery of "mails and duties" from their own

tenantry. The owners of baronies did not readily acquiesce in being deprived

of their higher authority, and some of them continued to appoint their

officers of justiciary long after such appointments could exist only in

name.

A new judicial system supervened. Of every

county, the Lord Lieutenant was appointed High Sheriff, while under him, yet

of independent authority, was nominated as Sheriff-Depute, an advocate who

had at least three years' practice in the Court of Session. The

sheriff-depute was authorized to hold occasional courts, but his duties were

chiefly to consist in considering appeals from the judgment of his

substitutes.

For the office of sheriff-substitute was

required no special qualification, persons of local respectability being

willing, like London vestrymen, to undertake a round of arduous and irksome

duties, rewarded solely by the dignity of office. Our lamented friend, the

late Dr Hugh Barclay, sheriff-substitute of Perthshire, in one of his

entertaining publications, facetiously refers to a sheriff substitute, who,

"practising as an apothecary, dispensed justice and medicine alike in

scruples, and was conversant with injections and ejections alike; he could

also purge witnesses."

At length the importance of securing an

effective sheriff' substitute was so generally recognized that in 1787 a

small salary was allowed. This was, about twenty years later, fixed at £200,

the appointment being still conjoined with some other office. In 1825 it was

ruled that the qualifications of every sheriff-substitute should, on his

appointment, be certified by the President of the Court of Session, also by

the Justice Clerk. Increased emoluments were also provided; these have been

augmented by subsequent acts.

To the sheriff and his substitute belong

extensive criminal jurisdiction, but the more important causes are, at the

discretion of the Lord Advocate and his deputies, reserved for the Court of

Justiciary. The sheriff and his substitute may try criminal causes with or

without a jury; they may inflict imprisonment for a year, or impose

penalties to the extent of fifty pounds.

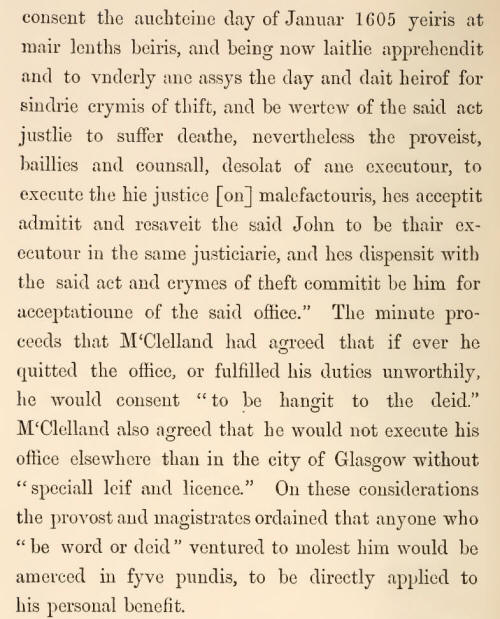

A dempster or doomster was associated with the

court of Parliament; he was Indicator Parliamenti, the conclusions of

Parliament being expressed by his voice. The office of heritable dempster to

Parliament was, by Robert II. in 1349, confirmed to Andrew Dempster of

Cariston. By David Dempster in 1476 were claimed before the Lords Auditors

"ten pundis amerciament of fee ilk parliament," also a fee of each justice

ayre held in Forfarshire,—claims which the Auditors allowed. On the 7th

October 1476, judgment was given in a cause by the mouth of Alexander

Dempster, in presence of the king sitting in the Parliament-house with the

crown on his head, and the sceptre in his hand. From the earlier times a

dempster was connected with every court which exercised criminal

jurisdiction. When a criminal was convicted and sentence of death recorded,

the dempster was called upon to repeat the sentence aloud. On a handbell

being rung by the presiding judge, the dempster entered the court. After

repeating the words of the sentence, he added, "And this I pronounce for

doom." If the dempster was not forthcoming or his duty was imperfectly

discharged, it was held that a death sentence might not be carried out. At a

circuit court held in Glasgow on the 10th. May 1723, Margaret Fleck, a

married woman, was, on the charge of rough-handling her infant child so as

to cause its death, declared guilty of murder and sentenced to death. The

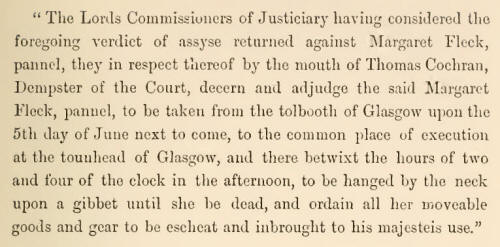

sentence is in the Justiciary Record entered thus:

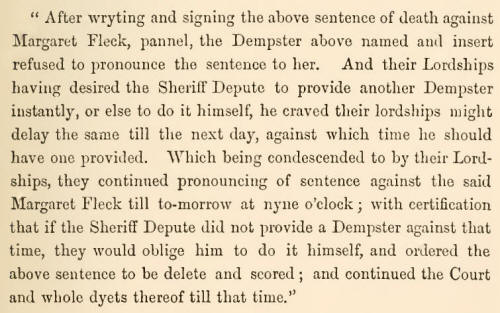

But Thomas Cochran, dempster and executioner of

Glasgow, would not make valid a sentence which the evidence (as it appears

on the record) did not justify. Undeterred. by his refusal, and the

universal sympathy of the people audibly expressed, the two circuit judges,

Lords Dun and Pencaitland, sanctioned the following, minute:-

Next morning one Robert Yeats, in consideration

of his being appointed dempster of the court, made the doom legal by

pronouncing it.

On the 16th March 1773 the Commissioners of

Justiciary abolished the office of dempster, and decreed that sentence

should be pronounced by the presiding judge, and afterwards read by the

Clerk. The abolition arose from an indecent exhibition in the High Court,

thus described by Sir Walter Scott. The office of dempster leaving become

unexpectedly vacant, one Hume, who had been sentenced to transportation as

an incendiary, consented temporarily to fulfil the office. Brought into

court to pronounce sentence of death upon a fellow prisoner, he omitted the

duty, but warmly reproved the judges for the severe sentence they had

imposed upon himself. Hume was forcibly ejected, and it was forthwith

determined to avoid the recurrence of so unseemly a demonstration. Early in

the present century Lord Justice Clerk Eskgrove introduced the English

custom, whereby the judge in pronouncing sentence of death wears a black

cap.

It has been alleged that in regalities connected

with ecclesiastical establishments, dempsters were unemployed. This is an

error. In seeking to extirpate heresy by burning the devoted confessors,

Resby and Craw, Bishop Wardlaw of St Andrews appointed as dempster and

executioner to the regality a person named Wan, whose office became

hereditary in his family. The hangman's acres, situated at Gair Bridge, near

St Andrews, are still in possession of Wan's representatives. Till the year

1773 ordinary sentences passed in court were publicly intimated by the macer.

The dempster of court usually executed the

sentence which he pronounced. An executioner was appointed to each principal

town. He was usually styled "the lockman," since in right of office he

possessed the privilege of helping himself to a lock or handful of farm

produce from every sack in the market-place. The hangman's measure was

subsequently determined by a timber cap or iron ladle, given by the

magistrates to every executioner on his appointment. Time executioner of

Stirling's collecting cap is preserved in the museum of that burgh.

A century ago, when capital sentences were

becoming less frequent, and hence the executioner's office less needful,

disposers of grain began to hold that the summary opening of their sacks and

the appropriation of their produce was an intolerable infliction. At

Dumfries market in 1781 a grain dealer named Johnstone deforced the burgh

executioner in his attempt to open his sacks, and in consequence was

sentenced to imprisonment. Put the magistrates who gave judgment,

apprehending that Johnstone's example might induce a general resistance,

sought the advice of counsel. By the legal authority consulted, the

executioner's claim and the magisterial action upon it were approved ; but

the demand continuing to induce complaint, it was in 1796 wholly withdrawn,

while the executioner's salary, payable by the burgh, was proportionably

increased. Till the close of the century every burgh lockman had his free

house and stated salary, varying from £8 to £10 sterling, together with a

special fee for every execution.

The lockman of Edinburgh was an officer both of

the Justiciary Court and of the municipality. From the Exchequer he received

a salary of five pounds, while latterly, in commutation of his market

privilege, he had granted him by the Town Council a weekly allowance of

twelve shillings. The execution fee considerably varied. In 1780 James

Alexander, lockman of Edinburgh, was by the city chamberlain paid for

service at an execution 13s. 4d., with a fee of 2s. 6d. for the use of his

rope. Subsequently the lockman received two guineas at every execution.

The Edinburgh executioner was arrayed in grey

trousers and vest, with a black velvet coat, trimmed with silver lace. The

corporation evinced especial care that he should be properly habited in

executing his office upon notable offenders. In reference to the execution

of the Regent Morton the Burgh Records present the following entry: "2 June

1581,—The prouest, baillies, and counsale vnderstanding that James, Eric of

Mortoun, is to be execut to the deid afternone for certaine crymes of lese

maiesty [high treason], ordains Androw Stevinsoun for honour of the towne to

caus mak ane new garment and stand of claythis of the townis liveray to

thair lokman with expeditious, and Johne Robertsoun, thesaurer, to refound

to him the expenssis."

The Edinburgh lockman had his dwelling in the

Fishmarket Close, and was expected to occupy a seat specially allocated to

him in the Tolbooth Church. In his "Traditions of Edinburgh," Dr Robert

Chambers remarks that the lockman, John Dalgleish (frequently named in the

"Heart of Midlothian") was a regular communicant, but was accommodated at a

special table when all the other communicants had retired.