In 1793, and the succeeding years, the whole strength

and resources of the United Empire were called into action. In the

northern corner of the kingdom a full proportion of its disposable

resources was produced. A people struggling against the disadvantages of

a boisterous climate, and barren soil, could not be expected to

contribute money. But the personal services of the young and active were

ready, when required, for the defence of the liberty and independence of

their country. The men whom these districts sent forth, in the hour of

danger, possessed that vigour and hardihood peculiar to an agricultural

and pastoral life. As a proof of this, in late years, when typhus and

other epidemic diseases were prevalent in the South, it was so different

in the mountains, that, except in cases where infection was carried from

the Low country, few instances of typhus or other contagious distempers

occurred, and where they actually broke out, they did not spread, as

might naturally have been expected, from the confined and small

dwellings of the Highland peasantry,—a fact only to be accounted for

from their habitual temperance, and that robust vigour of constitution

produced by sobriety and exercise.

It may, therefore, be allowed that the effective

national defence which the agricultural population afford

the State is to be valued beyond a numerical force of another

description, in so far as a man, whose strength of constitution

enables him to serve his country for a term of years, though subjected

to privations and changes of climate, is more valuable than the man

whose constitution gives way in half the time. This remark applies

forcibly in the present instance. Indeed, where sickness has prevailed

among Highland soldiers, it has in general been occasioned less by

fatigue, privations, or exposure to cold, than from the nature of the

provisions, particularly animal food, and from clothing unnecessarily

warm. [In 1805, the second battalion of the 78th regiment, newly

raised, and composed of nearly 600 boys from the Highlands, was

quartered in Kent where many of the finest looking lads were attacked

with inflammatory diseases, preceded by eruptions on the skin, arising

entirely from the quantity of animal food suddenly introduced into the

system, previously accustomed to barley and oatmeal, or vegetable diet.

The stomachs of many rejected the quantity of animal food supplied, and

it was not till the following year that they were fully seasoned.]

In the march through Holland and Westphalia in 1794 and 1795, when the

cold was so in-tense that brandy froze in bottles, the

Highlanders, consisting of the 78th, 79th, and the new recruits of the

42d, (very young soldiers), wore their kilts, and yet the loss was

out of all comparison less than that sustained by some other corps.

[During the whole of that campaign, from the landing at Ostend,

in June 1794, till the embarkation at Bremenlee, in May 1795, the number

killed and died of sickness in the 42d regiment was only twenty-six men.]

Producing so many defenders of the liberty, honour, and independence of

the State, as these mountains have done, and of which an aggregate

statement will be given, they might have been saved from a system which

tends ultimately to change the character, if not altogether to extirpate

their hardy inhabitants. We have heard of the despotic institutions of

the Mesta in Spain, which provide that the lands and pastures

shall be cleared for the royal flocks, who are driven from district to

district for subsistence. The monopoly of farms, which expatriates a

numerous and virtuous race, is a species of Mesta, greatly more ruinous

to the ancient inhabitants than that so justly complained of in Spain.

Whether it proceeds from the privileges of an absolute monarch, or the

power of engrossing wealth, we find that monopoly and despotism are

frequently analogous in their ultimate result, although they may differ

in the means to which they may resort for their attainment.

Individual severity as certainly generates

disaffection to the commonwealth, as the political sins and oppressions

of the government. However, the loyalty of Highlanders is not easily

alienated; for, although the engrossing of farms, and removal of the old

occupiers, caused such discontent in the county of Ross, that the people

broke out in open violence [See Article 42d

Regiment, vol. I. page 416.] in the year 1792, and the recruiting

for the 42d and other regiments was materially affected, yet, whenever

the general welfare and honour of the country were called in question,

and war declared, all complaints seemed to be buried in oblivion. And as

the Frasers, who had been one of the most active, numerous, and

efficient clans in the Rebellion of 1745, were the first, in the year

1756, to come forth in his Majesty's service, under the very leader who

had headed them at Culloden, and, in like manner, in the American war,

when the 71st, or Fraser's Highlanders, was the first regiment embodied;

so now, in the same country, whither, but two years before, troops had

been ordered to repair, by forced marches, to quell the riotous

discontents of the people, the first regiment raised in the late war was

completed in a few months, after letters of service had been granted to

the late Lord Seaforth. When completed it was numbered the 78th (the old

establishment of the army being 77 regiments), the regiment raised by

his predecessor the Earl of Seaforth, in the year 1779, having the same

number. This regiment, however, was not raised with the same expedition

as in former times. Probably some lurking feel-ings of dissatisfaction

at the late proceedings and depopulations still remained. The desolate

appearance of the once populous glens, the seats of happiness and

contentment, too strongly commemorated these hated proceedings;

especially as the people were, at the same time, uncertain whether a

similar fate awaited themselves. But, notwithstanding of these appalling

discouragements of patriotic and chivalrous feeling, the first

establishment of the regiment was completed, and embodied by

Lieutenant-General Sir Hector Munro at Fort George on the 10th of July

1793. Five companies were immediately embarked for Guernsey, where they

were brigaded with the other troops under the command of the Earl of

Moira. The other five companies landed in Guernsey in September 1793.

This was an excellent body of men, healthy, vigorous,

and efficient; attached and obedient to their officers, temperate and

regular; in short, possessing those principles of integrity and moral

conduct, which constitute a valuable soldier. The duty of officers was

easy with such men, who only required to be told what duty was expected

of them. A young officer, endowed with sufficient judgment to direct

them in the field, possessing energy and spirit to ensure the respect

and confidence of soldiers, and prepared, on every occasion, to show

them the eye of the enemy, need not desire a command that would

sooner, and more permanently, establish his professional character, if

employed on an active campaign, than that of 1000 such men as composed

this regiment.

Among these men desertion was unknown, and corporal

punishment unnecessary. The detestation and disgrace of such a mode of

punishment would have rendered a man infamous in his own estimation, and

an outcast from the society of his country and kindred. Fortunately for

these men, they were placed under the command of an officer well

calculated for the charge. Born among themselves, of a family which they

were accustomed to respect, and possessing both judgment and temper, he

perfectly understood their character, and ensured their esteem and

regard. Many brave honest soldiers have been lost from the want of such

men at their head. The appointment of a commander to a corps so

composed, is a subject of deep importance. Colonel Mackenzie knew his

men, and the value which they attached to a good name, by tarnishing

which they would bring shame on their country and kindred. In case of

any misconduct, he had only to remonstrate, or threaten to transmit to

their parents a report of their misbehaviour. This was, indeed, to them

a grievous punishment, acting, like the curse of Kehania, as a perpetual

banishment from a country to which they could not return with a bad

character. For several years, during which he commanded the regiment, he

seldom had occasion to resort to any other restraint. The same system

was followed up with such success by his immediate successors,

Lieutenant-Colonels Randoll Mackenzie, John Mackenzie (Gairloch), and

Alexander Adams, who successively commanded the regiment, that, after

being many years in India, "very little change occurred in the behaviour

of the men, except that they had become more addicted to liquor than

formerly. Selling regimental necessaries, or disorderly conduct in

barracks, were very uncommon, and the higher crimes totally unknown.

They were steady and economical, lived much among themselves, seldom

mixed with other corps, were much attached to many of their officers,

and extremely national. The climate of India preventing the officers

from so frequently visiting or being so much among them as when in

Europe, lessened the knowledge and intimacy that had previously

subsisted between them, but by no means did away their reliance and

confidence in each other." No officer enjoyed this confidence more than

Colonel Adams. Although not a Celtic Highlander of Scotland, he was a

Celt of Wales; and had he been from the Highlands of Ross, he could not

have been more acceptable to the soldiers, who Were fortunate in having,

for many years, a commander who so fully appreciated the peculiar traits

of their dispositions. He joined the regiment at the formation when very

young, entered readily into their feelings and peculiarities, and looked

upon them with more indulgence than many of their own countrymen.

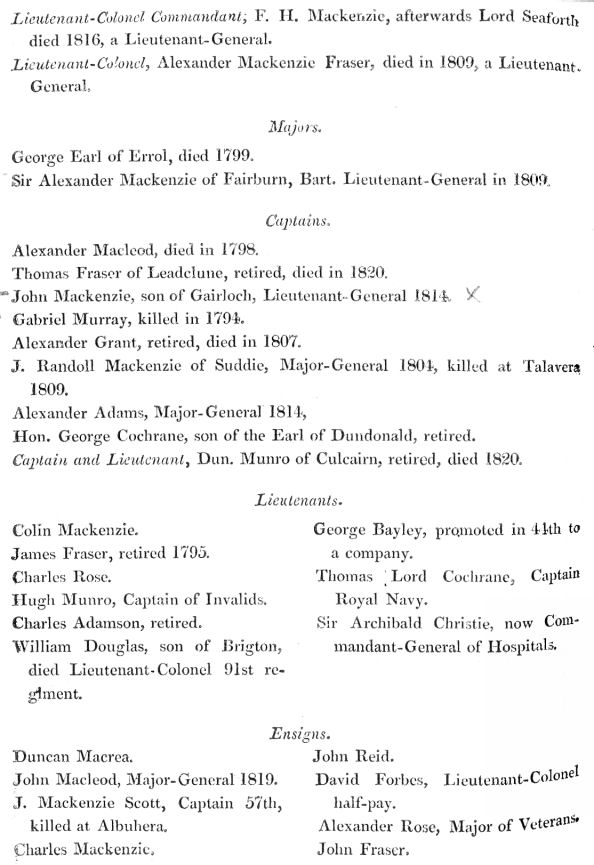

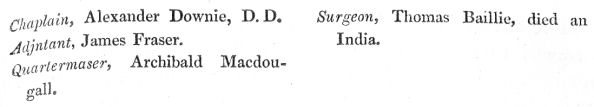

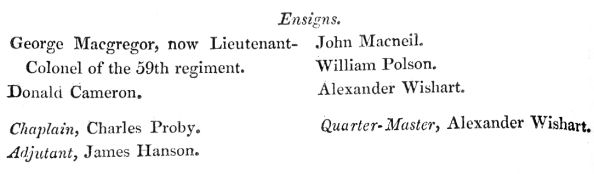

The following is a list of the original officers.

Commissions dated 8th of March 1793.

In September 1794, the 78th, along with the 80th

regiment, embarked from Guernsey to join an expedition form-jric under

the command of Major-General Lord Mulgrave, intended to occupy Zealand.

By an unpardonable neglect, the troops were put on board transports

recently arrived from the West Indies, with a number of prisoners, of

whom many had died of fever on the passage. Without any inspection, the

same bedding was served out to the troops, who, as might have been

anticipated, caught the infection. By great care it was, however,

prevented from spreading; and when the fleet reached Flushing, the 78th,

79th, 80th, 84th, and 85th, received orders to join the Duke of York's

army on the Waal. Lord Mulgrave was to return with the other corps to

England. In the middle of October the Highlanders reached Tuil, and

marched from thence to the village of Roscum, on the Bommil Wart on the

Maese. The opposite bank was occupied by the enemy in force. Nothing

occurred beyond popping shots across the river. One of these causing a

false alarm, an emigrant Dutch artillery officer, by some

misapprehension or ignorance of the language, fired a gun loaded with

case shot, and desperately wounded Lieutenant Archibald Christie of the

78th, and a sergeant, who were standing in the range of the shot, giving

directions to a sentinel. Lieutenant Christie, who is now

Commandant-General of Hospitals, suffered extremely, for many years,

from the severity of the wound received by so unfortunate and provoking

an occurrence.

[While the troops lay at this post, under the command

of Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Mackenzie Fraser, much attention was

excited by the regularity with which a battery

on the other side of the river opened a smart fire whenever any portion

of the troops happened to be under arms, although not seen by the enemy.

At last it was observed,

that, before the fire commenced, a wind-mill, on the

same side with the British, always put its

wings in motion. This excited suspicion, and it was discovered that the

miller had concerted signals with the enemy. The man was seized, and

ordered to be hanged immediately, but, by the humane interference of

Colonel Mackenzie, he was pardoned. Instances, such as this are not

perhaps sufficient to indicate the general feelings of a country, but so

many occurred during this campaign, that it is not easy to withhold

concurrence in the general opinion, that the Dutch were hostile to the

British on every occasion when they could display that feeling with

impunity.]

The enemy having laid siege to Nimeguen, the 78th was

ordered to reinforce the garrison, from which a sortie was made, on the

4th of November, by the 8th, 27th, 28th, 55th, 63d, and 78th

Highlanders, along with some cavalry and Dutch troops. In this their

maiden service, the Highlanders did justice to the expectations formed

of them. They moved forward under a very heavy fire, and leapt into the

trenches, in the midst of a French battalion drawn up ready to receive

them. These they attacked and overthrew with the bayonet, reserving

their powder till the enemy had fled beyond reach. An affair of such

close fighting was soon decided, with a loss to the British of only 12

rank and file killed; 12 officers, 10 sergeants, 149 rank and file,

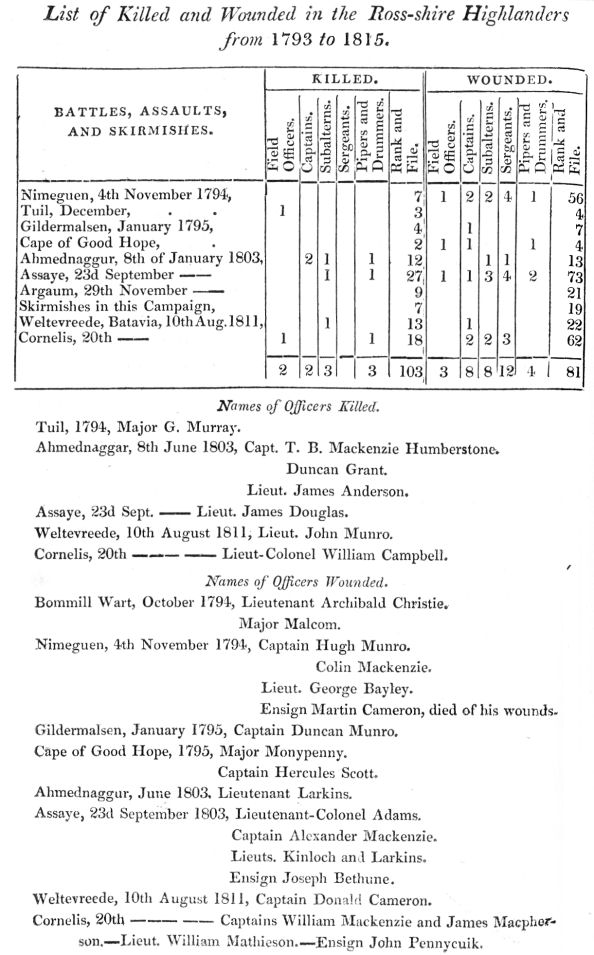

wounded; of whom the Highlanders lost 7 rank and file killed; Major

Malcom, Captains Hugh Munro and Colin Mackenzie, Lieutenant Bayley,

Ensign Martin Cameron, (who died of wounds), and 4 sergeants, and 56

rank and file, wounded.

[The greater part of the

wounds were given by musketry, when the troops were advancing to the

batteries. A musket ball entered the outward edge of Captain Munro's

left eye, and passing under the bridge of the nose through the right,

carried away both eyes, without leaving the least mark or disfiguration,

farther than the blank in the eyes shot away. He was quite well in a few

weeks, and has since taught himself to write a short letter with much

correctness, and to play on several musical instruments. He is now a

judicious agriculturist, and spirited improver of his estate. As the

Sergeant Major leapt into the trenches, a ball struck him high up on the

outside of the right thigh, passed down to the knee, and entering the

left leg in the calf, came out at the ankle, but, as it touched no bone,

it did not disable him above ten days, notwithstanding the circuitous

direction it followed, running round so many bones.]

The enemy having advanced with an overpowering force,

Nimeguen was evacuated on the 6th, and, on the 10th, the Highland

regiment was removed to the 3d brigade or reserve, consisting of the

12th, Lieutenant-Colonel Perryn, 33d, the Honourable

Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Wellesley, and the 42d, Major William Dickson;

the whole being under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander

Mackenzie Fraser.

In this position they lay till the 29th of December,

when the enemy crossed the Waal on the ice, at Bommill. The right wing

of the British immediately marched, and concentrated at Khiel, under the

command of Major-General David Dundas, and, the same night, moved

forward on a position of the enemy at Tuil, which, however, they

evacuated on the approach of the British. Brevet-Major Murray, and some

men of the Light company 78th, were killed by a distant cannonade, as

the troops were advancing.

The army lay on the snow for two nights, and, on the

31st, were put into barns till they were removed to Gildermalsen, on

which place the enemy advanced in force on the 5th of January 1795. The

78th was drawn up in two wings in front of the village, leaving the road

open between the wings, and having the Light company, with two howitzer

guns, in advance. The 42d, in support, occupied the different avenues to

the village; the 12th and 19th regiments were at some distance to the

right, and the 33d, with a squadron of the 11th dragoons, in the

advanced post of Meteren. The enemy made his attack with such vivacity,

that the outposts were quickly driven in. A regiment of French Hussars,

dressed in an uniform similar to that of the emigrant regiment of

Choiseul in our service, pushed forward under cover of this deception,

and gallopped along the road, with great fury, crying "Choiseul,

Choiseul!" This so far succeeded, that they were allowed to get close to

the advanced company of the 78th before the truth was discover-ed, when

they were instantly attacked and checked, but not sufficiently to

prevent a part pushing, at full speed, through the intervals between the

two wings towards the village. Here they were met by the Light company

of the 42d, whose fire drove them back, and scattered them in an

instant. When the attacking column of the enemy's infantry perceived

that their cavalry had got through, beyond the first line, they advanced

with great boldness, singing the Carmagnole March. The 78th reserved

their fire till the enemy nearly closed upon them, when it was opened

with such effect, that they were driven back in great confusion. The

repulse of the cavalry and infantry was so

complete and expeditious, that the loss of the Highlanders was trifling;

[When the light troops and cavalry in

advance were forced to retire, they left the guns in possession of the

enemy, who pushed so far forward, that their cavalry got mixed with the

Light infantry; but a company of the 78th, under Lieutenant David

Forbes, stationed a little to the right of the road, fired with such

good aim, as to kill and wound many of the enemy, without touching any

of our own people, although in the line of the fire.] that of the

78th being Captain Duncan Munro wounded, and a few soldiers killed and

wounded. [At this

time one of those artifices was exhibited by which the French, on many

occasions during the Revolutionary war, laid the foundation of their

victories. An inhabitant, in one of the quarters, opened his stores, and

sold liquor to the soldiers in large quantities, at a price so much

below value as to create suspicion that the object was to intoxicate the

soldiers, and render them incapable of resistance. This was confirmed in

the morning by the apprehension of a man at the outposts, sent forward

by the enemy to ascertain the effects of the stratagem. It is well known

that the French frequently tamper ed with their enemy, and that they

found individuals infamous enough to sacrifice their own honour, and the

best interests of their country. But they have ever evinced their

respect for the character of the British army so far, that there is not

an instance in the late war of an attempt to seduce an officer from his.

duty. But, although this respect has been shown to the character of

officers, the unhappy propensity of our soldiers to liquor was not

thought proof against temptation, and might have succeeded in this

instance, had not the distribution of the liquor been checked.]

After this affair the regiment accompanied the

movements of the army through this campaign, and in the severe march to

Deventer, the difficulty of which, occasioned by the depth of the

falling snow, and the intense cold, has been only surpassed by the late

disastrous campaign of the French in Russia. On the 28th of April they

reached Bremen, embarked in a few days afterwards, and landed at Harwich

on the 10th of May; and, after different movements, were, early in

August, put under the command of the Earl of

Moira, in the neighbourhood of Southampton, together with the 12th,

80th, and 90th regiments, preparatory to an expedition in support of the

French Royalists in La Vendée.

Of this battalion 560 were of the same country and

character as the first, and 190 from different parts of Scotland. In

August they embarked at Fort George for England, and remained stationary

there till April 1795, when six companies embarked in an expedition

under Vice-Admiral Keith, Elphinstone and Major-General James Henry

Craig, for an attack on the Cape of Good Hope. After the capture of this

colony, which was purchased with the loss of a few men killed, and Major

Monypenny, Captain Hercules Scott, and five men, wounded, the battalion

remained in garrison under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander

Mackenzie of Fairburn.

I now return to the first battalion, which, as

already mentioned, together with the 12th, 80th, and 90th regiments, was

placed under the command of the Earl of Moira, and detached in August

1795, under Major-General W. Ellis Doyle, as the advance of a more

considerable armament, to follow under his Lordship, to make an

impression in favour of and to support the Royalists in La Vendee. The

Royalists had established a strong position at Quiberon, but they were

unfortunately attacked by a great force, and overpowered, before the

reinforcement from England arrived. Being thus enabled to land in face

of the numerous armies which the French had brought to the coast, the

expedition landed on Isle Dieu, and established a post on that island,

from whence they menaced different parts of the opposite coast, till

January 1796, when the place was evacuated, and the troops returned to

England. The 78th marched to Pool, where orders were received to embark

for the East Indies. Both battalions were to be formed into one, and the

junior officers of each rank to retire on full pay till otherwise

provided for.

At this time Colonel Lord Seaforth resigned,

retaining his rank in the army. On the 6th of

March the regiment embarked at Portsmouth, and landed at the Cape of

Good Hope on the 1st of June 1796. Both battalions were now

consolidated, the supernumerary officers and men ordered home, and a

very effective and healthy body of men (consisting of 970 Highlanders,

129 Lowlanders, and 14 English and Irish) formed, which sailed for

Bengal on the 10th of November, (having previously witnessed the

surrender of a large Dutch fleet at Saldanha Bay), and, after a long

passage, in which the scurvy made its appearance on board some of the

ships, but not to a great extent, landed at Fort William on the 12th of

February 1797, and, a few days afterwards, marched to Burhampore.

During six years' residence in different cantonments

in Bengal, no material event occurred. The corps sustained throughout a

character every way exemplary. The commanding officer's system of

discipline, and his substitution of censure for punishment, attracted

much attention. [The temperate habits of the

soldiers, and Colonel Mackenzie's mode of punishment, by a threat to

inform his parents of the misconduct of a delinquent, or

to send an unfavourable character of him to his native country,

attracted the notice of all India. Their

sobriety was such, that it was necessary to restrict them

from selling or giving away the usual allowance of liquor to

other soldiers. ] Every friend of humanity, and of the honour of

the British army, must earnestly wish that the same system were more

generally adopted. It might, doubtless, be extended, by attention to the

feelings and peculiar habits of men. If a sense of honour, national

spirit, and pride, were once instilled and kept alive among them, the

main point would be gained. When fully persuaded that the character and

good name of their country were confided to their charge, they

would feel the weight of such a responsibility, and would be

convinced that courage is only one of the many virtues necessary to

sustain and perpetuate the national honour.

In reference to Colonel Mackenzie Fraser's mode of

discipline, I may add, that, in the twenty-five years during which the

first battalion has been established, there has no been one desertion

among the men enlisted in the Highlands. [There

were in this battalion nearly 300 men from Lord Seaforth's estate in the

Lewis. Several years elapsed before any of these men were charged, with

a crime deserving severe punishment. In 1799 a man was tried and

punished. This so shocked his comrades, that he was put out of their

society as a degraded man, who brought shame on his kindred. The

unfortunate outcast felt his own degradation so much, that he became

unhappy and desperate; and Colonel Mackenzie, to save him from

destruction, applied and got him sent to England, where his disgrace

would be unknown and unnoticed. It happened as

Colonel Mackenzie had expected, for he quite recovered his character. By

the humane consideration of his commander, a man was thus saved from

that ruin which a repetition of severity would have rendered inevitable.]

Lieutenant-Colonel Mackenzie Fraser left India in

1800 and was succeeded in the command by Colonel J. Randoll Mackenzie,

who also returned to England in 1802, when the command devolved upon

Lieutenant-Colonel John Mackenzie (Gairloch), and then on

Lieutenant-Colonel Adams; but in all these changes the system of

discipline continued the same. In February 1803 the regiment embarked at

Fort William in Bengal, and, landing at Bombay in April, were ordered to

join the army commanded by Colonel John Murray. After some movements

under this officer, the battalion was removed to the army commanded by

Major-General the Honourable Arthur Wellesley, and placed in brigade

with the 80th and the 1st European and 3d Native battalions, under

Lieutenant-Colonel Harness. Lieutenant-Colonel Wallace commanded the

brigade formed of the 74th, with the same number of European and Native

regiments. The Cavalry brigade, of the 19th Light dragoons and Native

cavalry, were under Lieutenant-Colonel Maxwell. Each corps of infantry

and cavalry had two guns attached. A corps of pioneers, and a

considerable force of Mysore and Mahratta horse, accompanied the army.

The whole were well equipped for service, and had a sufficient supply of

provisions. In short, no precautions were neglected to secure that

success which soon distinguished its exertions. The order of march was

equally well regulated. The line of baggage, an object of much

importance in Indian warfare, kept close to the columns; both flanks and

the rear being covered by corps of Native horse. In this order the army

commenced its march on the 2d of June 1803, and, after many delays,

encamped, early in August, within eight miles of Ahmednaggur. On the 8th

of the month General Wellesley resolved to attempt the town by assault.

The army was formed in three columns, the flank companies of the 74th

and 78th Highlanders being the advanced guard. The other two columns

were led by the battalion companies of the same corps. The latter met

with little resistance, the principal efforts of the enemy being

directed against the advanced guard, which had also to overcome a

perplexing obstacle. The walls were high and narrow, without a rampart,

or any place for the soldiers to obtain a footing on, after they had

gained the top. Unable to advance, and disdaining to retreat, every man

who had reached the top was killed on the spot; but, notwithstanding,

the enemy were so intimidated, that they surrendered the town without

farther resistance. The 78th regiment lost Captains F. Mackenzie

Humberstone and Duncan Grant, Lieutenant Anderson, and 12 men, killed,

and Lieutenant Larkins and 5 men wounded. [On

this occasion the spirit and animation of a subaltern of the 78th

regiment (now Major-General Sir Colin Campbell), particularly attracted

General Wellesley's notice. He was appointed extra aid-de-camp the

following day, and has ever since been in his family and confidence. It

is remarkable that this officer, like his illustrious patron, has never

been wounded, although present in every battle fought by the Duke of

Wellington from Assaye to Waterloo.]

After this service, the army resumed its forward

movements. In the progress of many long and harassing marches, the

General made arrangements so admirable and so easily comprehended, that

no orders were given for halting or marching, or taking ground to the

right or to the left, beyond the tap of a drum, or a signal from a

bugle-horn. The troops were so well provided with supplies, and all

movements so regulated, that the soldiers were never unnecessarily

exposed; and, although many of the marches were very fatiguing, all

impediments were so well guarded against, and foreseen, that on no

occasion was it necessary to be on the march at unseasonable hours.

On the 21st of September, the army found itself

within a short march of two numerous bodies of the enemy, under the

command of Scindia and the Rajah of Berar. Colonel Stephenson, with a

detachment of the Bombay army, was also within a day's march ; and the

two British commanders having met on the 22d, measures were concerted

for a joint attack on the enemy, who, it was feared, would not hazard ,

a general engagement. Each army continued its separate line of march •

and, on the morning of the 23d, General Wellesley received intelligence

that the enemy's cavalry were already on their retreat, and the

infantry, then only distant a few miles, preparing to follow. The case

being now too urgent to wait for Colonel Stephenson, the General ordered

the troops to march instantly, while he himself hastened forward with

the cavalry to reconnoitre. This little army had been already weakened

by the separation of two battalions detached to Poonah, and a third left

at Ahmednaggur. There now only remained the 19th Dragoons, and the 4th,

5th, and 7lh Native cavalry; the 74th and 78th Highland regiments; with

the first battalion of the 2d, the first battalion of the 4th, the first

battalion of the 8th, the first battalion of the 10th, and the second

battalion of the 12th Native infantry; in all, about 4700 men, with

twenty-six field-pieces. When the leading division of the army reached

within a short distance of the enemy's position, the line of battle was

formed as follows: The first line consisted of the Picquets of the army

on the right, the 78th on the left, and the 8th and 10th Native

regiments in the centre; the second line was composed of the 74th

regiment, with the 12th and 4th Native battalions; the Cavalry were in

reserve in the third line.

To oppose this force, the enemy was supposed to have

one hundred pieces of cannon, and 30,000 men, including the Light

troops, who had gone out to forage in the morning (and were those

reported to have marched), but who returned before the close of the

action. The infantry were dressed, armed, and accoutred in the same

manner as the Seapoys in the Company's service, and well disciplined by

French and other European officers. The artillery was well served, and

was observed to fire with considerable celerity. The two Rajahs,

attended by their ministers, were in the field. The opposing armies were

divided by the Kaitna, a small stream, with high banks and a deep

channel, impassable to cavalry and guns, except at the fords. The enemy

were drawn up on a rising ground, with the cavalry on the right, and

their line extended to the village of Assaye on the left.

On General Wellesley's approach to reconnoitre, the

enemy commenced a cannonade, the first shot of which killed one of the

escorts. As the first attack was to be made on the enemy's left, it was

necessary to cross a ford of the Kaitna considerably within reach of

their cannon, which played with effect on the column of march. During

this movement, the enemy's first line changed position to the left, to

oppose a front to the intended attack. Their second line remained in

their original position, by which means it was at right angles to the

first. The first line of the British formed parallel to that of the

enemy, separated about 500 yards, the left being directly opposite to

the right of the enemy, and the second and third lines in the rear.

During the formation of this order, the enemy's great guns fired with

precision and rapidity, several of the shots piercing through the three

lines to the rear. This was answered by the

guns of the first line, which had already so many draught oxen disabled,

that the soldiers were obliged to draw the cannon.

The order of battle was now formed; and the picquets

being named as the battalions of direction, the General ordered the line

to advance in a quick pace, without firing a

shot, but to trust all to the bayonet. This order was received with

cheers, and instantly obeyed. It was soon perceived, however, that the

leading battalion, composed of the picquets, had diverged from the line

of direction, which made it necessary to halt the whole front line. This

was a critical moment. The troops had got to the summit of a swell of

the ground, which had previously sheltered their advance, and the enemy,

believing that the halt proceeded from timidity, redoubled their

efforts, firing chain-shot and every missile they could bring to bear

upon the line. General Wellesley, dreading the influence of this

momentary halt on the ardour of the troops, rode up in front of a Native

battalion, and, taking off his hat, cheered them in their own language,

and gave the word to advance again. This was also received with cheers,

and instantly put in execution. When the 78th was within 150 yards of

the enemy, they advanced in quick time, and charged. At this instant

some European officers, in the service of the enemy, were observed to

mount their horses and fly. The infantry, thus deserted by their

officers, broke and fled with such speed, that few were overtaken by the

bayonet: but the gunners held firm to their guns; many were bayoneted in

the act of loading, and none gave way till closed upon by the bayonet.

After this charge, the 78th quickly reformed line,

and, preparing to advance on the enemy's second line, wheeled to the

right, thus showing a front to their left. During these operations on

the left, the 74th pushed forward to the front, over an open plain, and

suffered exceedingly from the fire of the enemy's artillery. They were

the longer exposed this destructive fire, from the difficulty they

encountered of getting through a prickly-pear hedge. Many of the men

having lost their shoes, their feet were much torn and pierceed.

In this state, exposed to the fire of thirty

pieces of cannon, and with one half of their number killed and wounded,

large body of the enemy's cavalry advanced to charge; but the rapid

advance of Lieutenant-Colonel Maxwell, with the 19th dragoons, gave a

most timely support to this regiment. At this critical moment, he

charged the enemy in flank, drove them off the field, and thus enabled

the remains of the 74th to take up their position in the front line.

The first battalion of the 12th Native infantry, who,

at the same time, had also advanced, with great steadiness, from the

second line, suffered exceedingly. The army was now in one line, the

78th on the left, and the 74th on its immediate right. The enemy kept up

a heavy fire from the village, numbers coming up from the banks of the

river, and others who had thrown themselves on the ground as dead, and

had been passed over by our men, now started up and gained possession of

their own guns, which had been abandoned on the charge of our first

line. From these they commenced a heavy fire from the rear, at the same

time that a body of cavalry appeared on the left flank preparing to

charge. To resist this, the left wing of the Highlanders was thrown back

some paces on its right, and, at that instant, Lieutenant D. Cameron,

who had been left with a party to protect two guns which could not be

brought forward owing to their draught oxen being killed, now forced his

way through, and joined his regiment most seasonably, when all were in

anxious expectation of the farther orders of the General. This was an

important moment, for it now seemed almost as if the battle had only

commenced, or was to be fought over again. With an unbroken line of the

the enemy in front, keeping up a constant fire of cannon, flanked by

batteries of round shot on their right, grape from

the rear, and with cavalry threatening the left; with all

this in view, and exposed to so severe a trial, the silence and

steadiness of the troops were highly honourable to their

character. But they were not long kept in a state of suspense. The

General ordered the cavalry to charge the enemy's squadron on the left

(who did not wait the attack), and, directing the line to attack to

their front, led the 78th, the 19th dragoons, and 7th Native cavalry to

the rear, and attacked the enemy who had collected there in considerable

force. Part of this force retreated, but in such good order, that one

brigade stood the charge of the 19th Light dragoons, in which Colonel

Maxwell, a brave and zealous officer, was killed. The Highlanders had

considerable difficulty in clearing that part of the field to which they

were opposed, and in recovering the cannon. The enemy made a strong

resistance, forcing the regiment three times to change its front, and to

attack each party separately, none giving way till attacked; and while

the regiment moved against one, the others kept up a galling fire which

continued till the whole were driven off the field. At this time the

cavalry, which had been detached by the enemy in the morning, returned;

but, when a party of Mysore horse marched against them, they retreated,

and the fire ceased entirely at half-past four o'clock.

Thus ended the battle of Assaye, the most desperate

and best contested that ever was fought in India. On no occasion did the

enemy display more bravery, or serve their guns with more precision,

steadiness, and effect. The brilliancy of this victory will be more

conspicuous, when we consider that it was gained over a force six times

more numerous, that 98 pieces of cannon, and military stores, in

proportion, were taken on the field of battle, and that 1200 men were

killed, and 3000 supposed to be wounded. The British loss was 21

officers killed, and 30 wounded., The 78th lost Lieutenant Douglas, and

27 rank and file, killed; Captain Alexander Mackenzie, Lieutenants

Kin-loch and Larkins, Ensign Bethune, 4 sergeants, and 73 rank and file,

wounded. Lieutenant-Colonel Adams was knocked off his horse by the blow

of a spent ball on the shoulder, but as he was able to remount and keep

the field, he did not include himself in the list of wounded. Lieutenant

Thomas Fraser was also slightly wounded. Indeed, there were only two

officers of the regiment that escaped without some contusion or bruise,

but, following the example of their commanding officer, their names did

not appear among the wounded.

After the wounded and sick were settled in quarters,

the army resumed active operations. A variety of movements and several

partial skirmishes ensued, until the 29th of November, when the enemy

were discovered drawn up in regular line of battle, on a plain in front

of the village of Argaum. The troops moved forward, in one column, to

the edge of the plain, in sight of the hostile army, which was nearly

equal in number to that at Assaye, but neither so well disciplined nor

so well appointed; the artillery were also less numerous (being only 38

pieces) and less expert. General Wellesley's army, on the other hand,

exceeded its former amount, having been reinforced by Colonel

Stephenson's division, consisting of the 94th or Scotch Brigade, six

Native regiments of infantry, and two of cavalry. A small village lay

between the head of the British columns and the enemy's line. The

cavalry were ordered up, and formed in close column behind this village.

The right brigade passed the village, and formed line in its front; and

the other corps followed and formed in succession. The enemy were about

1200 yards distant. The instant the leading picquet passed the village,

the enemy fired twenty pieces of cannon in one volley.

Courage in some men, individually as well as

collectively, is a firm constitutional principle, equally steady and

uniform in all situations, and not to be shaken by any unexpected

assault or alarm. The courage of others, again, is sometimes ardent and

enthusiastic, and may be led to the cannon's mouth; but not being an

inherent principle of action, and depending often on contingencies, it

is not constant, and may fail in moments of the greatest need. Here the

Native picquets, and two battalions which had been eminently

distinguished at Assaye, only two short months before, were so

panic-struck with this noisy reception, which in fact did no execution,

that, notwithstanding the greatest exertions of their officers, they

retired in the utmost confusion behind the village, leaving the picquets

of the 78th and the artillery standing alone in the field. The 78th

regiment instantly marched up and formed line with the picquets and

artillery. Other corps also moved forward in succession, and, through

the exertions of their officers, the battalions which had retired were

also brought up again into line.

The army was drawn up in one line of fifteen

battalions, the cavalry forming a Reserve or second line, the 78th being

on the right, and next to them the 74th; and the 91th forming the left

of the line. When this regiment (which was supported by the Mysore

horse) reached and formed on their proper ground, the whole moved

forward, the 78th directing its march against a battery of nine guns,

which supported the enemy's left. As they approached, a body of 800

infantry rushed out from behind the battery, and, at full trot, made for

the intervals between the 74th and 78th. Surprised at this daring

advance, the regiments obliqued their march to close the interval, and

with ported arms moved forward in quick time to meet their assailants.

But a muddy deep ditch (before unperceived) intervened, and prevented an

actual shock with the bayonet. The enemy, however, stood by the ditch,

with a resolution almost unparalleled in Eastern troops, firing till

their last men fell. The following morning upwards of five hundred dead

bodies were found lying on the ground where these men had been drawn up.

They were a party of desperate fanatics, who fought from a religious

principle.

This was the only serious attempt made by the enemy.

An attack was made by Scindia's cavalry on the left of Colonel

Stephenson's division, but they were quickly repulsed by the 6th Native

infantry, and the whole line immediately gave way, leaving 38 pieces of

cannon on the field, and was pursued beyond Argaum, where, the sun

having now set, the infantry halted, but the cavalry continued the

pursuit by moonlight, till nine o'clock. The

victory was complete, and, unlike that of Assaye, was purchased with

little loss, which fell principally on the 78th regiment.

Colonel Harness, compelled, by an illness of which he

died some time afterwards, to resign the command of the right brigade,

it devolved upon Colonel Adams; Major Hercules Scott, as field-officer

of the day, commanding the picquets of the line, the command of the 78th

regiment fell to Captain James Fraser.

No particular notice was taken of the conduct of the

two Highland regiments at Assaye, where so much was done, while at

Argaum the General says of them, "The 74th and 78th deserved, and

received, my thanks." [At the battle of

Assaye, the musicians were ordered to attend to the wounded, and carry

them to the surgeons in the rear. One of the pipers, believing himself

included in this order, laid aside his instrument, and assisted the

wounded. For this he was afterwards reproached by his comrades. Flutes

and hautboys they thought could be well spared, but for the piper, who

should always be in the heat of the battle, to go to the rear with the

whistlers, was a thing altogether unheard of. The unfortunate

piper was quite humbled. However, he soon had an opportunity of playing

off this stigma, for, in the advance at Argaum, he played up with such

animation, and influenced the men to such a degree, that they could

hardly be restrained from rushing on to the charge too soon, and

breaking the line. Colonel Adams was, indeed, obliged to silence the

musician, who now, in some measure, regained his lost fame.]

On the 2d of December active operations recommenced,

and, on the 13th, the strong fort of Gawelghur was taken by assault.

This exploit concluded the hostile operations of this army against the

enemy; but their fatigues, from marching and countermarching, were

incessant, till the 20th July 1804, when the 78th reached Bombay. More

men and officers fell sick in the last month than in the previous

campaign. And, as it often happens, when troops are placed in a state of

rest after an active campaign, they continued sickly for a considerable

time.

In May 1805 five companies were ordered to Baroda in

the Guzzerat, and in July a reinforcement of 100 recruits from Scotland

was received. In the succession of reinforcements at different times,

from the second battalion, from the Scotch Militia, and from recruiting

parties, this regiment was uncommonly fortunate. At Goa, whither it had

been removed from Bombay in 1807, it embarked for Madras in the month of

March 1811, when the strength of the corps was 1027, and only five men

were left behind from sickness. Of these 835 were Highlanders, 184

Lowlanders, 8 English, and 9 Irish. But the numerical strength of this

fine body of men was less to be estimated than their character, personal

appearance, efficiency, and health. Upwards of 336 were volunteers from

the Perthshire, and other Scotch Militia regiments, and 400 were drafts

from the second battalion, which had been seasoned by a service of three

years in the Mediterranean. Such was the stature of many of the men

that, after the Grenadier company was completed from the tallest men,

the hundred men next in height were found too tall, and beyond the usual

size of the Light infantry.

The harmony which so frequently subsisted between

Highland corps and the inhabitants of the countries where they have been

stationed, has been frequently observed. In Goa it appears to have been

the same as elsewhere. The Conde de Surzecla, Viceroy of Portuguese

India, on the departure of the regiment from under his command, embraced

the opportunity "to express his sentiments of praise and admiration of

the regular, orderly, and honourable conduct of his Britannic Majesty's

78th Highland Regiment, during the four years they have been under his

authority, equally and highly creditable to the exemplary discipline of

the corps, and to the skill of the excellent commander; and his

Excellency can never forget the inviolable harmony and friendship which

has always subsisted between the subjects of the Regent of Portugal, and

all classes of this honourable corps."

The regiment did not land at Madras, but were placed

under the orders of Lieutenant-General Sir Samuel Achmuty, and formed

part of the force intended for the conquest of Java. They sailed on the

30th of April.1811, the 78th being in the second

brigade commanded by Lieutenant- Colonel Adams.

In August the fleet reached Batavia, and the army

disembarked without opposition at Chillingching, a few miles east of the

city. After some days passed in landing and in necessary preparations,

the advance of the army, under Colonel Rollo Gillespie, moved forward,

and, on the 8th, took possession of the city of Batavia, abandoned by

the enemy, who retreated to Weltevreede. The army followed to Batavia on

the 10th, while Colonel Gillespie, with the advance, moved forward

towards the enemy's cantonment at Weltevreede, from which they retired

to a strong position two miles in front of Cornells. [As

several of the officers were preparing to move forward, they were

suddenly taken ill, in consequence of swallowing some drugs which had

been infused into their coffee by a Frenchman

who kept the house where they were quartered. They, however, soon

recovered, and as a punishment to their trecherous landlord, forced him

to drink his own medicine, and poured down his throat

a small part he had left. ] This post was occupied by 3000 of

their best troops, and strengthened by an abbatis of felled trees.

Colonel Gillespie made an immediate attack, and carried it at the point

of the bayonet. The enemy made an obstinate resistance, but were

completely routed, with the loss of all their guns. In this smart

affair, "the flank companies of the 78th, (commanded by Captains David

Forbes and Thomas Cameron), and the detachment of the 89th, particularly

distinguished themselves." Lieutenant John Munro and 13 men of the 78th

were killed, and Captain Cameron and 22 men wounded.

The interval from the 10th to the 20th was occupied

in preparing batteries against Cornelis. This was a level parallelogram

of 1600 yards in length, and 900 in breadth, having a broad and deep

river running on one side, with ditches cut around the other three. The

old fort of Cornelis stood on the bank of the river. To this fort six

strong redoubts had been added by General Daendels. Each of these was

mounted with cannon, and so situated, that the guns of the one commanded

and supported the other. The space within was defended by traverses and

parapets, cut and raised in all directions, and intended as a cover for

the musketry while the great guns fired over them. The whole were

defended by 5000 men. Besides the outward ditches, small canals had been

cut, in different directions, within this fortified position. The attack

was made on the 20th. Colonel Gillespie, with the flank battalions,

supported by Colonel Gibbs, with the 59th, and the Bengal Volunteers,

were to attack the main front opposite Cornells. The Light company,

under Captain David Forbes, and the Grenadiers of the 78th, under

Captain Donald Macleod, formed part of this attack. The battalion of the

78th, under Lieutenant-Colonel William Campbell, were to push forward to

the assault by the main road. Every attack was completely successful.

The enemy was forced from every traverse and defence, as the troops

advanced, but not without strong resistance. By some strange oversight

on the part of the Dutch, the ditch over which the battalion companies

of the 78th had to pass was left dry. Captain James Macpherson pushed

forward with two companies,' and took possession of the dam-dike which

kept back the water from the ditch, and prevented the enemy from cutting

it. In this affair, Captain Macpherson was wounded in a personal

rencountre with a French officer. Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell was

mortally wounded as the regiment advanced to the ditch, which they

crossed, and carried the redoubt and defences in their front, with a

spirit and ardour which the enemy could not resist. After an obstinate

contest, the enemy were overpowered, and retreated by the side of the

camp which had not been attacked, leaving upwards of 1000 men killed,

and a great number wounded; while that of the British was only 91 rank

and file killed, and 513 wounded. The 78th lost Brevet

Lieutenant-Colonel William Campbell, and 18 rank and file, killed; and

Captains William Mackenzie and James Macpherson, Lieutenant Mathiesion,

Ensign Pennycuik, 3 sergeants, and 62 rank and file, wounded. This

conquest was soon followed by the surrender of the whole colony.

The regiment was stationed in different parts of the

country till September 1816, when they embarked for Calcutta. During

this period of four years, the men suffered exceedingly from climate. [In

the summer of 1813, several officers of the 78th, in a convalescent

state, were removed to the village of Probolingo, near Sourabaya, a spot

celebrated for the salubrity of the climate. On the 18th of June they

visited a native of the country, a man of large property in the

neighbourhood; and, as they were riding home in the evening, they were

attacked by a body of men, a species of banditti, who occasionally make

excursions, and infest that part of the country. Lieutenant-Colonel

Fraser and Captain Macpherson, who had distinguished himself at Cornells,

were killed, along with their landlord, who had rode along with them.

The other officers, Captain Cameron, Lieutenant Robertson, and Ensign

Cameron, escaped with difficulty.] That fine body of men which,

in 1811, had sailed from Madras 1027 strong, was now greatly reduced in

numbers; and, as often happens from sickness by climate, the stoutest

and largest men had first fallen. The regiment was assembled at Batavia

from the distant stations, and, on the 15th September, embarked on board

the Frances Charlotte and another transport. The Charlotte, with six

companies on board, had a favourable voyage till the morning of the 5th

of November, when, at two o'clock, the ship struck on a rock, twelve

miles distant from the small island of Prepares. Fortunately, the

weather was moderate; but the ship, being under a press of sail, struck

with such force, that she stuck fast to the rock, and in fifteen minutes

was filled with water to the main-deck.

Then was displayed one of those examples of firmness

and self-command, which are so necessary in the character of a soldier.

Although the ship was in the last extremity, and momentarily expected to

sink, there was no tumult, no clamorous eagerness to get into the boats;

every man waited orders, and obeyed them when received. The ship rapidly

filling, and appearing to be lodged in the water, and to be only

prevented from sinking by the rock, all hope of saving her was

abandoned. Except the provisions which had been brought up the preceding

evening for the following day's consumption, nothing was saved. A few

bags of rice, and a few pieces of pork, were thrown into the boats,

along with the women, children, and sick, and sent to the island, which

was so rocky, and the surf so heavy, that they had great difficulty in

landing. It was not until the following morning that the boats returned

to the ship. A part of the rock was dry at low water; and as many as

could stand there (140 men) were removed on a small raft, with ropes to

fix themselves to the points of the rock, in order to prevent their

being washed into the sea by the waves which dashed over the rock at

full tide. The rock was about 150 yards from the ship. It was not till

the third day that the boats were able to carry all in the ship to the

island, while those on the rock remained without sleep, and with very

little food or water, till the second day, when water being discovered

on the island, a supply was brought to them.

During all this time the most perfect order and

resignation prevailed, both on the island and on the rock.

Providentially the weather continued favourable, or those on the rock

must have been swept into the sea. In the evening of the third day, the

Po, a country ship, bound for Penang, appeared in sight, and soon

afterwards bore down towards the wreck, of which a small part now only

remained above water. A large boat was immediately sent, and forty men

taken off the rock; and soon afterwards a lesser boat was sent. Too many

men crowding on board, and throwing the boat to one side, she upset; but

the men got back to the rock. In the mean time, the commander of the Po,

believing himself short of provisions, or from some other cause,

proceeded the same evening on his voyage to Penang, leaving his boat and

the unfortunate sufferers to their fate. However, on the morning of the

10th, after being five days in this state, they were cheered by the

sight of a large ship a few miles distant, and steering towards the

island. This was the Prince Blucher, Captain Weatherall, perceiving the

wreck, and the people on the rock, he immediately sent boats, and took

all the people on board, and the following morning the women and the

sick were taken from the island; but the wind blowing fresh, the ship

was obliged to keep well out to sea, to avoid the rocks; and there being

no safe anchorage, the communication with the island was much

interrupted. The weather continued unfavourable till the 13th, when it

blew a gale of wind; and Captain Weatherall seeing no prospect of being

able to take the whole on board in time to reach Calcutta, with his

stock of provisions, for so great an addition to his numbers, he

determined to sail for that place; and, arriving there on the 23d of

November, the Marquis of Hastings, the Governor-General, immediately

dispatched two vessels with provisions and clothes, and on the 6th of

December they made the island of Prepares. The people there were by that

time nearly reduced to the last extremity. The. allowance of provisions

(a glass full of rice and two ounces of beef for two days to each

person) was expended, and they had now only to trust to the shell-fish

which they picked up at low water. These soon became scarce; and they

had neither lines to catch fish, nor fire-arms to kill the birds and

monkeys, the only inhabitants of the island, which

is small and rocky, covered with low trees and brushwood. In this

deplorable state, the men continued as obedient, and the officers had

the same authority, as on parade. Every privation was borne in common.

Every man who picked up a live shellfish carried it to the general

stock, which was safe from the attempts of the half-famished sufferers.

Nor was any guard required. However, to prevent any temptations,

sentinels were placed over the small store. But the precaution was

unnecessary. No attempt was made to break the regulations established,

and no symptoms of dissatisfaction were shown, except when they saw

several ships passing them without notice, and without paying any regard

to their signals. These signals were large fires, which might have

attracted notice when seen on an uninhabited island. Captain Weatherall

required no signal. He met with some boards and other symptoms of a

wreck, which had floated to sea out of sight of the island, and,

suspecting what had happened, immediately steered towards it. To his

humanity, the safety of the people on the rock may, under providence, be

ascribed; for, as the violence of the gale was such as to dash the ship

to pieces, leaving no part visible in a few hours, the men must have

been swept off the rock at its commencement.

Five men died of weakness; several were drowned in

falling off the kind of raft made to convey them from the ship to the

rock; and some were drowned by the surf in going on shore: in all,

fourteen soldiers and two Lascars were lost. Unfortunately, the gale

that destroyed the ship blew off the island, so that no part of the

wreck floated on shore. Had it been otherwise, some things might have

been carried back to the island. [Since the

publication of the first edition, I have been informed, that, after the

Po set sail, and left the people on the wreck to their fate, several of

the men behaved in a most improper manner, and, giving themselves up to

despair, seized upon some liquor in the cabin, and threw themselves into

a state of intoxication, which added to the wretchedness of their

situation. The Lascars gave up entirely, and could not be made to exert

themselves in any way; No part of this misconduct attached to the people

on the island, whose conduct was exemplary throughout.]

The vessels which took the men off this island had an

expeditious passage back to Calcutta, where they landed on the 12th of

December. After the men had been refreshed and new clothed, they

embarked for England, in the end of February 1817, on board the Prince

Blucher, Captain Weatherall, to whose humanity they in a great measure

owed their lives. They sailed on the 1st of March, and landed in

Portsmouth in June. From thence they embarked for Aberdeen, and in a few

weeks were removed to Ireland.

At this time a report was pretty generally spread

that the three Highland regiments, the 42d, 78th, and 92d, had been

ordered out of Scotland under a conviction that they were not to be

trusted at a time when disturbances were expected in Glasgow and other

manufacturing towns. This unfounded and malicious report must have

originated in what was considered to be an unexpected removal of those

National corps to Ireland, particularly the removal of the 78th, in a

few weeks subsequent to their return to their native country, after a

course of honourable service, and after an absence of twenty-three

years, without having had an opportunity of seeing their friends and

their kindred. The character of these soldiers is now too well

established to admit, of any distrust or want of confidence in their

performance of their duty. The honour and good name of a soldier ought

to be like the virtue of Caesar's wife, not only pure, but unsuspected.

The honour of Highland soldiers has hitherto been well supported, and

Ross-shire has to boast that the 78th has all along maintained the

honourable character of their predecessors. All those who value the

character of a brave and virtuous race may look with confidence to this

corps, as one of the representatives of the military and moral character

of the peasantry of the mountains" In this regiment, twenty-three have

been promoted to the rank of officers during the war. Merit thus

rewarded will, undoubtedly, have its due influence on those who succeed

them in the ranks.